多灶性甲状腺乳头状癌的临床病理及颈淋巴结转移特征

2017-03-31殷德涛韩飏张亚原李红强王勇飞柳桢苌群刚

殷德涛,韩飏,张亚原,李红强,王勇飞,柳桢,苌群刚

(郑州大学第一附属医院 甲状腺外科,河南 郑州 450052)

甲状腺癌是最常见的内分泌恶性肿瘤,而甲状腺乳头状癌(papillary thyroid cancer,PTC)是其中最常见的病理类型,占所有甲状腺癌的85%以上[1-2]。其恶性程度较低,预后较好,但长期病死率仍高达10%[3],这与甲状腺癌的转移复发有着紧密的联系。PTC主要的转移途径有3种:淋巴结转移、肿瘤的局部外侵以及远处转移,其中颈部淋巴结转移在PTC中尤为常见。有研究[4]表明大约有1/3的甲状腺癌患者在病程初期即存在可检测的淋巴结受累,而术前未检测到淋巴结肿大,术后病理发现存在微小淋巴结转移灶的患者更为常见。PTC常表现为多灶性,且病灶可位于单侧或双侧腺体内。有研究[5]认为多灶性PTC是由肿瘤的腺内转移引起的,另有研究[6]显示多发癌灶是多克隆起源。PTC一般以手术治疗为主[7],恰当的手术方式可以降低患者复发风险,改善预后,因此对于多灶性PTC的手术方式的选择较为重要。本文通过回顾性分析323例甲状腺癌患者资料,研究其中148例多灶性PTC与颈淋巴结转移的关系,探讨其手术方式的选择。

1 资料与方法

1.1 资料

收集2016年6月—2016年10月在郑州大学第一附属医院甲状腺外科行首次甲状腺手术并经术后病理证实为PTC的患者共323例。所有患者均为术前彩超可疑甲状腺癌,术前穿刺或术中快速冷冻病理提示为PTC,术后常规石蜡切片确诊为PTC。多灶性PTC定义为单侧或双侧腺体内存在2个或2个以上癌灶者。在本组病例中,多灶性PTC共148例。

1.2 手术方式

所有患者均由同一治疗组医师行甲状腺全切除及中央区淋巴结清扫术,术前彩超报告有可疑颈侧区淋巴结肿大者行颈侧区淋巴结清扫术。术中注意解剖保护双侧喉返神经及甲状旁腺,并仔细结扎止血[8]。

1.3 统计学处理

数据分析采用SPSS 17.0统计软件,定量资料应用t检验,计数资料应用χ²检验,多因素分析采用Logistic回归分析,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 总体情况

所收集323例甲状腺癌患者中,男90例(27.9%),女233例(72.1%);年龄11~75岁,平均年龄44.9岁;肿瘤大小(最大径)平均为1.02 cm;单灶性甲状腺癌共175例(54.2%),多灶性甲状腺癌共148例(45.8%),其中115例(77.7%)为双侧多灶,另33例(22.3%)为单侧多灶。多灶组中99例(66.9%)癌灶数为2,49例(33.1%)癌灶数为3灶及以上。中央区淋巴结阳性者170例(52.6%),腺外浸润55例(17.0%),颈侧区淋巴结阳性48例(14.9%)。

2.2 多灶性PTC与单灶性PTC临床病理资料比较

对比148例多灶性PTC患者(多灶PTC组)与175例单灶性PTC患者(单灶PTC组),发现两组年龄、性别、及最大癌灶直径无统计学差异(均P>0.05),但多灶PTC组较单灶PTC组更易发生中央区、颈侧区淋巴结转移及腺外浸润(均P<0.05)(表1)。

表1 多灶性PTC与单灶性PTC临床病理特征比较Table1 Comparison of the clinicaopathologic features between multifocaland unifocalPTC

2.3 多灶性PTC不同癌灶数量与淋巴结转移的关系

148例多灶性PTC中,癌灶数量为2的患者共99例,癌灶数量大于2的患者49例,对癌灶数等于2与癌灶数为3个或以上的病例作进一步比较,发现随着癌灶数的增加,中央区及侧区淋巴结转移率增加,且更易发生腺外浸润(均P<0.05)(表2)。

表2 不同癌灶数量与淋巴结转移的关系Table2 Relationship between tumor number and lymph node metastasis

2.4 多灶性PTC中央区淋巴结转移因素分析

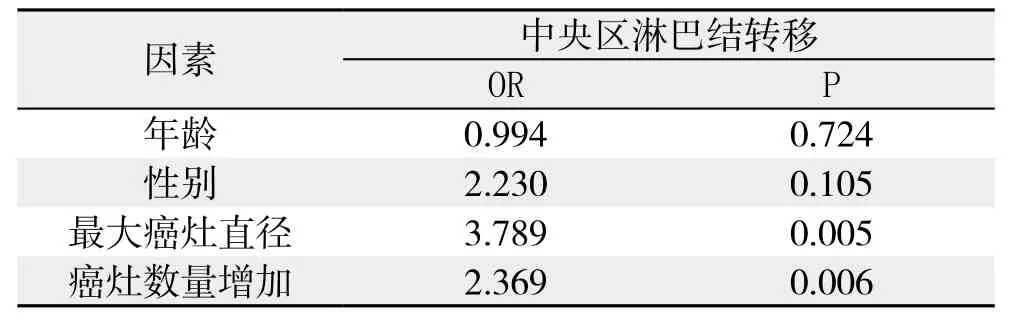

对多灶性PTC的中央区淋巴结转移进行Logistic回归分析,结果显示,最大癌灶直径(P=0.005)与癌灶数量的增加(P=0.006)均为中央区淋巴结转移的独立相关因素,而年龄的增长与性别则与中央区淋巴结转移无明显关系(均P>0.05)(表3)。

表3 多灶性PTC中央区淋巴结转移的危险因素分析Table 3 Analysis of the risk factors forcentral neck metastasis of multifocal PTC

3 讨 论

多灶性是PTC的特点之一[9],与其转移复发有着密切的关系,是判断其预后的重要指标。本研究通过对多灶性PTC的分析,发现多灶组颈淋巴结转移率较单灶组增高,腺外浸润发生也高于单灶组。进一步对多灶组中癌灶数量进行分析,我们发现随着癌灶的增加,颈淋巴结转移率及腺外浸润的发生率也进一步增加。该结果提示多灶性PTC具有更强的侵袭性,癌灶数量越多,恶性程度越高。这与很多学者[10-12]的看法一致,多灶性癌更容易复发,预后较差。

本研究又对多灶性PTC中央区淋巴结转移的危险因素进行分析,发现癌灶的最大直径的增大与数量的增加均增加了中央区淋巴结转移的风险,所以对于癌灶数较多的甲状腺癌患者,即使术前彩超未发现中央区有可疑肿大淋巴结,仍不能排除其中有转移淋巴结的可能。有研究[13-15]显示,约有30%~60%的颈淋巴结阴性的甲状腺乳头状癌患者存在隐匿的淋巴结转移灶。因此,多灶性PTC的诊断和手术方式选择很重要。

多发癌灶的诊断大多可经术前彩超及术中快速病理来明确。至于手术方式的选择,多数专家均推荐行甲状腺全切除或近全切除,降低复发的风险,避免出现二次手术,也为术后的放射性碘治疗提供基础,且更利于患者进行随访[16-18]。而是否加行中央区淋巴结清扫是近年来探讨的热点问题。2015年ATA指南[19]明确指出对于中央区淋巴结有明确转移的病例,应在全甲状腺切除的基础上加行中央区淋巴结清扫术。但临床上颈淋巴结阴性的患者也较为普遍。对于这些CN0期的患者,反对行中央区淋巴结清扫的学者[20]认为甲状腺全切除加中央区淋巴结清扫增加了术后并发症的发生,包括喉返神经损伤、及低钙血症。并且手术范围越大,出现低钙血症的几率就越高[21]。但有研究[22]表明在甲状腺全切除的基础上行中央区淋巴结清扫术仅增加了暂时性低钙血症的发生,而永久性低钙血症及喉返神经损伤的发生率较低。纳米碳在临床中的广泛应用也能显著降低术后低钙血症的发生,提高了中央区淋巴结清扫的精确度[23]。因此更多的学者[17,24]通过对多灶性PTC术后复发风险的研究,认为所有癌灶直径较大或癌灶数量较多者,除需行甲状腺全切除外,还应预防性清扫中央区淋巴结,从而有效地降低多灶性甲状腺癌的复发风险,避免再次手术。并且预防性的清扫中央区淋巴结能更准确的对患者术后进行TNM分期,便于制定进一步的治疗方案,利于随访[25]。因此,对于PTC的患者,应注意术前彩超中可疑恶性结节的数量,术中应注意快速冷冻病理所证实的癌灶个数,对于明确的多灶性PTC行甲状腺全切除加中央区淋巴结清扫术,术前彩超提示颈侧区有可疑肿大淋巴结者,建议加行颈侧区淋巴结清扫术。术后根据常规病理结果,行TSH抑制治疗或放射性碘131治疗。

综上,多灶性PTC具有更强的侵袭性,更易发生颈部淋巴结转移及腺外浸润。因而对于多灶性甲状腺癌的手术治疗,我们建议行甲状腺全切除加中央区淋巴结清扫,术前彩超显示颈侧区有可疑肿大淋巴结时应加行颈侧区淋巴结清扫术。术后根据常规病理结果行放射性碘131治疗及TSH抑制治疗并定期复查以期预防复发。

[1] Yin DT, Yu K, Lu RQ, et al. Clinicopathological significance of TERT promoter mutation in papillary thyroid carcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf),2016, 85(2):299–305. doi: 10.1111/cen.13017.

[2] Yin de T, Xu J, Lei M, et al. Characterization of the novel tumorsuppressor gene CCDC67 in papillary thyroid carcinoma[J].Oncotarget, 2016, 7(5):5830–5841. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6709.

[3] Yin DT, Yu K, Lu RQ, et al. Prognostic impact of minimal extrathyroidal extension in papillary thyroid carcinoma[J].Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, 95(52):e5794. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005794.

[4] Sancho JJ, Lennard TW, Paunovic I, et al. Prophylactic central neck disection in papillary thyroid cancer: a consensus report of the European Society of Endocrine Surgeons (ESES)[J]. Langenbecks Arch Surg, 2014, 399(2):155–163. doi: 10.1007/s00423–013–1152–8.

[5] Wang W, Zhao W, Wang H, et al. Poorer prognosis and higher prevalence of BRAF (V600E) mutation in synchronous bilateral papillary thyroid carcinoma[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2012, 19(1):31–36.doi: 10.1245/s10434–011–2096–2.

[6] Kuhn E, Teller L, Piana S, et al. Different clonal origin of bilateral papillary thyroid carcinoma, with a review of the literature[J].Endocr Pathol, 2012, 23(2):101–107. doi: 10.1007/s12022–012–9202–2.

[7] 殷德涛, 王庆兆. 分化型甲状腺癌的治疗[J]. 中国普通外科杂志,2007, 16(1):7–9.Yin DT, Wang QZ. Treatment of differentiated thyroid carcinoma[J].Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2007, 16(1):7–9.

[8] 殷德涛, 李香华, 李红强, 等. 甲状腺术后出血的原因及处理: 附8例临床分析[J]. 中国普通外科杂志, 2015, 24(11):1592–1595. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005–6947.2015.11.018.Yin DT, Li XH, Li HQ, et al. Causes and treatment of postthyroidectomy hemorrhage: a clinical analysis of 8 cases[J].Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2015, 24(11):1592–1595. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005–6947.2015.11.018.

[9] Wang W, Su X, He K, et al. Comparison of the clinicopathologic features and prognosis of bilateral versus unilateral multifocal papillary thyroid cancer: An updated study with more than 2000 consecutive patients[J]. Cancer, 2016, 122(2):198–206. doi:10.1002/cncr.29689.

[10] Zheng XQ, Wang C, Xu M, et al. Progression of solitary and multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma - a retrospective study of 368 patients[J]. Chin Med J (Engl), 2012, 125(24):4434–4439.

[11] Kuo SF, Lin SF, Chao TC, et al. Prognosis of multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma[J]. Int J Endocrinol, 2013, 2013:809382. doi:10.1155/2013/809382.

[12] Qu N, Zhang L, Ji QH, et al. Number of tumor foci predicts prognosis in papillary thyroid cancer[J]. BMC Cancer, 2014,14:914. doi: 10.1186/1471–2407–14–914.

[13] Laird AM, Gauger PG, Miller BS, et al. Evaluation of postoperative radioactive iodine scans in patients who underwent prophylactic central lymph node dissection[J]. World J Surg, 2012, 36(6):1268–1273. doi: 10.1007/s00268–012–1431–5.

[14] Wang Q, Chu B, Zhu J, et al. Clinical analysis of prophylactic central neck dissection for papillary thyroid carcinoma[J]. Clin Transl Oncol, 2014, 16(1):44–48. doi: 10.1007/s12094–013–1038–9.

[15] Jiang LH, Chen C, Tan Z, et al. Clinical Characteristics Related to Central Lymph Node Metastasis in cN0 Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study of 916 Patients[J]. Int J Endocrinol, 2014, 2014:385787. doi: 10.1155/2014/385787.

[16] Konturek A, Barczyński M, Nowak W, et al. Risk of lymph node metastases in multifocal papillary thyroid cancer associated with Hashimoto's thyroiditis[J]. Langenbecks Arch Surg, 2014,399(2):229–236. doi: 10.1007/s00423–013–1158–2.

[17] Iacobone M, Jansson S, Barczyński M, et al. Multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma--a consensus report of the European Society of Endocrine Surgeons (ESES)[J]. Langenbecks Arch Surg, 2014,399(2):141–154. doi: 10.1007/s00423–013–1145–7.

[18] Dong S, Xia Q, Wu YJ. High TPOAb Levels (>1300 IU/mL)Indicate Multifocal PTC in Hashimoto's Thyroiditis Patients and Support Total Thyroidectomy[J]. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg,2015, 153(1):20–26. doi: 10.1177/0194599815581831.

[19] Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer[J]. Thyroid, 2016, 26(1):1–133. doi:10.1089/thy.2015.0020.

[20] Kim SK, Woo JW, Lee JH, et al. Prophylactic Central Neck Dissection Might Not Be Necessary in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: Analysis of 11,569 Cases from a Single Institution[J].J Am Coll Surg, 2016, 222(5):853–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.02.001.

[21] 王勇飞, 殷德涛, 李红强, 等. 甲状腺癌术后低钙血症的临床分析[J]. 中华内分泌外科杂志, 2015, 9(6):484–486. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674–6090.2015.06.012.Wang YF, Yin DT, Li HQ, et al. Clinical analysis of hypocalcemia after thyroid cancer surgery[J]. Journal of Endocrine Surgery, 2015,9(6):484–486. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674–6090.2015.06.012.

[22] Mamelle E, Borget I, Leboulleux S, et al. Impact of prophylactic central neck dissection on oncologic outcomes of papillary thyroid carcinoma: a review[J]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 2015,272(7):1577–86. doi: 10.1007/s00405–014–3104–5.

[23] 宋韫韬, 张乃嵩, 王天笑, 等. 纳米碳在甲状腺乳头状癌中央区淋巴清扫中的应用[J]. 中国普通外科杂志, 2016, 25(11):1563–1567.doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005–6947.2016.11.007.Song YT, Zhang NS, Wang TX, et al. Application of carbon nanoparticles in central neck dissection for papillary thyroid carcinoma[J]. Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2016,25(11):1563–1567.

[24] Zhao Q, Ming J, Liu C, et al. Multifocality and total tumor diameter predict central neck lymph node metastases in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2013, 20(3):746–752. doi:10.1245/s10434–012–2654–2.

[25] 林晓东, 陈晓意, 黄宝骏, 等. 预防性颈中央区淋巴结清扫对cN0分化型甲状腺癌分期与复发危险度分层的意义[J]. 中国普通外科杂志, 2015, 24(5):633–637. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005–6947.2015.05.003.Lin XD, Chen XY, Huang BJ, et al. Significance of prophylactic central lymph node dissection in tumor stage classification and risk stratification of recurrence for cN0 differentiated thyroid carcinoma[J]. Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2015, 24(5):633–637.