中国结直肠癌预防共识意见(2016年,上海)*

2016-12-23中华医学会消化病学分会中华医学会消化病学分会肿瘤协作组

中华医学会消化病学分会 中华医学会消化病学分会肿瘤协作组

·共识与指南·

中国结直肠癌预防共识意见(2016年,上海)*

中华医学会消化病学分会 中华医学会消化病学分会肿瘤协作组

无论是遗传性(约占5%)还是散发性结直肠癌(colorectal cancer),环境因素均是影响其发生和进展的重要因素。因散发性结直肠癌(或称大肠癌)的发生途径大致分为腺瘤-腺癌途径(含锯齿状腺瘤引起的锯齿状途径)、炎-癌途径、denovo途径,结直肠癌的主要癌前疾病为结直腺瘤(colorectal adenoma,占全部结直肠癌癌前疾病的85%~90%,甚至更高)和溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC)等炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)。尽管结直肠可发生间质瘤和神经内分泌肿瘤等,但临床上通常将结直肠癌和腺瘤统称为结直肠肿瘤。多数结直肠癌确诊时已届中晚期,疗效不佳,故结直肠癌的早期发现和及早预防至关重要。有鉴于此,应重视结直肠癌的预防。结直肠癌的预防包括对上述癌前疾病的预防和治疗。结直肠腺瘤的一级预防即预防结直肠腺瘤的发生,结直肠腺瘤的二级预防即结直肠腺瘤摘除后预防再发(recurrence,或称复发,包括原处复发和他处再发)或恶变。上述两者应归属于结直肠癌的一级预防。结直肠癌的二级预防包括早期结直肠癌的内镜下处理和内镜随访以防止复发。70%的散发性结直肠癌与生活习惯有关[1],且66%~78%的结直肠癌可通过健康的生活习惯而避免[2]。内镜下摘除腺瘤可预防75%的结直肠癌[3],但摘除后的再发率高[4-6],仍需进行预防。无论是通过改善饮食等生活习惯,还是应用药物预防腺瘤的初次发生或摘除后再发或癌变,以及预防IBD癌变,均属于广义的结直肠癌的化学预防,为本共识意见涉及的内容。而综合预防的其他内容包括筛查、内镜下摘除腺瘤等则请参见中华医学会消化内镜学分会消化系早癌内镜诊断与治疗协作组、中华医学会消化病学分会消化道肿瘤协作组、中华医学会消化内镜学分会肠道学组和中华医学会消化病学分会消化病理学组于2014年联合颁布的《中国早期结直肠癌及癌前病变筛查与诊治共识意见(2014年11月·重庆)》[7]。

本共识意见是在2011年10月由中华医学会消化病学分会颁布的《中国结直肠肿瘤筛查、早诊早治和综合预防共识意见》[8]中综合预防部分内容的基础上,综合了近5年国际和国内相关研究的新进展而形成。由中华医学会消化病学分会及其肿瘤协作组主办、上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院消化学科暨上海市消化疾病研究所承办的《中国结直肠癌预防共识意见(2016年,上海)》研讨会于2016年5月8日在上海召开。

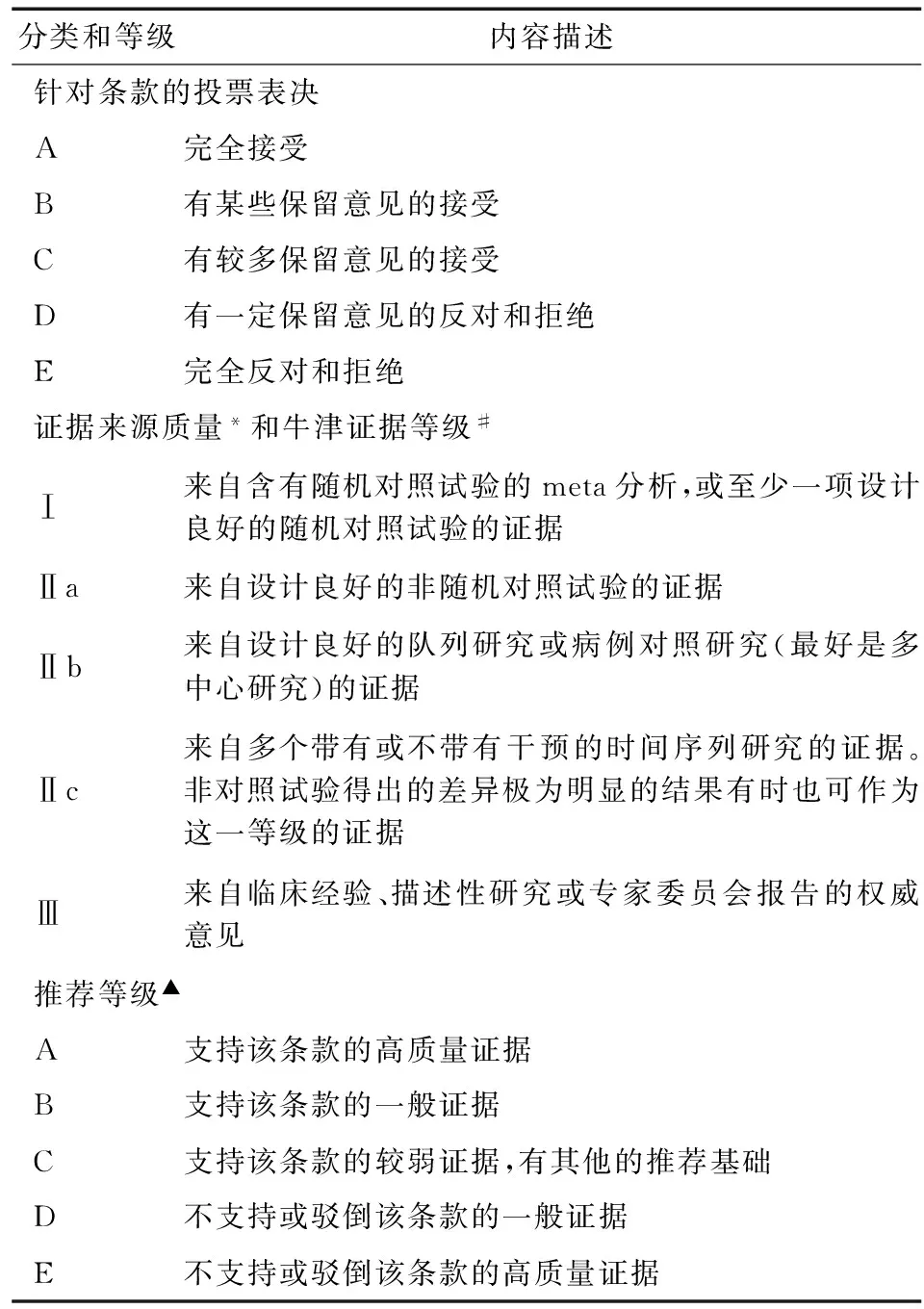

本共识意见包含32项条款,由中华医学会消化病学分会肿瘤协作组的主要专家撰写草稿;会前由来自全国各地的消化病学专家对共识意见草案进行了反复讨论和修改,会议期间首先听取了撰写小组专家针对每一条款的陈述,充分讨论后以无记名投票形式通过了本共识意见。条款的循证医学等级和表决等级见表1。每一条款投票意见为A或B者超过80%被视为通过;相反则全体成员再次讨论,第二次投票仍未达到前述通过所需要求,则当场修改后进行第三次投票,确定接受或放弃该条款。

表1 证据来源质量和推荐等级标准

*参照美国预防医学工作组的分级方法并作相应修改

#http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/

▲参照Sung等[9]的分级方法并作相应修改

一、散发性结直肠腺瘤的一级预防

第1条 高膳食纤维可能降低结直肠癌的患病风险

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:96.29%

膳食纤维与结直肠癌风险相关性的研究由来已久。纳入20项研究共10 948例结直肠腺瘤患者的meta分析[10]发现,高膳食纤维摄入与结直肠腺瘤的发生呈负相关[高膳食纤维摄入组与低摄入组的相对危险性(relative risk, RR)为0.72,95% CI: 0.63~0.83]。进一步亚组分析发现,高水果纤维摄入对结直肠腺瘤发生的RR为0.84(95% CI: 0.76~0.94),而高蔬菜纤维摄入为0.93(95% CI: 0.84~1.04),高谷物纤维摄入为0.76(95% CI: 0.62~0.92)。Trock等[11]对1990年前的37项观察性研究和16项病例对照研究进行总结,发现多数研究均支持高膳食纤维摄入可在一定程度上降低结直肠癌风险,膳食纤维摄入量最高组与摄入量最低组的比值比(odds ratio, OR)为0.57(95% CI: 0.50~0.64)。此后,有学者于2003年对欧洲多个国家和地区EPIC队列研究进行分析发现,膳食纤维摄入量最高组与摄入量最低组相比,结直肠癌的RR为0.58(95% CI: 0.41~0.85)[12];与Murphy等[13]于2012年再次综合EPIC研究数据得到的结论类似。但亦有研究提出相反的结论,Fuchs等[14]对88 757名中年女性开展长达16年的前瞻性队列研究,发现膳食纤维摄入量与结直肠癌发病风险无明显相关性(摄入量最高组对摄入量最低组的RR为0.95, 95% CI: 0.73~1.25)。Park等[15]对13项前瞻性研究进行了综合分析,亦发现源于果蔬或谷物的膳食纤维摄入量与结直肠癌风险均无相关性。来自我国的研究[16]证实,与健康对照者相比,进展性腺瘤患者膳食纤维摄入量少,粪便中短链脂肪酸含量降低,产生短链脂肪酸的肠道菌群减少。

需注意的是,蔬菜作为膳食纤维的重要来源之一,其摄入量与结直肠癌风险的相关性并不十分明显。Aune等[17]分析了19项前瞻性研究发现,增加蔬菜摄入量虽然可降低结直肠癌的相对风险,但幅度并不大。最新的一项meta分析[18]对日本的6项队列研究和11项病例对照研究进行分析,发现蔬菜摄入量与结直肠癌无明显相关性。类似的观点亦在其他多项研究[19-20]中得到了证实。但增加特定类型的蔬菜摄入量可能降低结直肠癌风险,如十字花科类食物的摄入量与结直肠癌风险呈显著负相关[21-22]。

第2条 减少红肉和加工肉类制品的摄入可能降低结直肠癌患病风险

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:89.74%

目前涉及肉类和加工肉类制品与结直肠癌发病风险的研究多以队列研究和病例对照研究为主,尚缺乏随机对照研究。就现有文献而言,绝大部分研究支持红肉(指牛肉、羊肉、猪肉等哺乳动物的肌肉组织)和加工肉类制品(腌制、熏烤、煎炸等的肉类食品)的摄入量与结直肠癌风险相关。依照证据等级,本共识意见提出的条款主要基于多项meta分析的结果。

Larsson等[23]对2006年前的部分前瞻性研究行meta分析,发现红肉摄入量最高组的结直肠癌相对风险为摄入量最低组的1.28倍(95% CI: 1.15~1.42),加工肉类制品摄入量最高组的患病风险为最低组的1.20倍(95% CI: 1.11~1.31);剂量-效应分析表明每日多摄入120 g红肉,其结直肠癌的RR为1.28,每日多摄入30 g加工肉类制品,RR为1.09。其他两项meta分析[24-25]亦得出类似的结果。Smolińska等[26]对2009年前的22项研究进行了分析,发现红肉摄入量超过50 g/d即可增加结肠癌的风险(RR=1.21, 95% CI: 1.07~1.37),而每日食用红肉的次数增多(超过1次/d)亦可增加结直肠癌的发病风险。Chan等[27]对2011年前的红肉和(或)加工肉类制品与结直肠癌关系的26篇相关报道进行汇总分析,发现红肉和加工肉类制品与结直肠癌或结肠癌风险具有相关性,且非线性的剂量-效应分析证实结直肠癌的风险指数与红肉和加工肉类制品的摄入量几乎呈线性的增长关系,但当摄入量超过140 g/d后RR趋于稳定。有研究[28]将两大队列研究(Nurses’ Health Study和Health Professionals Follow-up Study)的相关数据进行合并分析,亦得出加工肉类制品是结直肠癌,特别是远端结肠癌的危险因素之一的结论。最新一项meta分析[29]则对不同类型的红肉与结直肠癌发生风险进行分析,结果提示牛肉与结直肠癌(RR=1.11, 95% CI: 1.01~1.22)和结肠癌(RR=1.24, 95% CI: 1.07~1.44)风险呈正相关,与直肠癌无明显相关性;羊肉与结直肠癌风险呈正相关(RR=1.24, 95% CI: 1.08~1.44);猪肉摄入量与结直肠癌风险无明显相关性。

鉴于不同国家和地区饮食习惯的不同,有研究对中国、日本、韩国等东亚地区国家的数据进行分析。Lee等[30]发现日韩两国结直肠癌发病率与其国民食肉量的升高趋势相一致。经常食用肉类与男性近端结肠癌和女性直肠癌发病风险升高相关[31]。日本的一项队列研究[32]共纳入了13 894名男性和16 327名女性,随访8年,发现结直肠癌风险与肉类或红肉的摄入量无明显相关性,加工肉类制品摄入量的升高仅与男性结直肠癌的罹患风险相关(RR=1.98, 95% CI: 1.24~3.16)。另一项规模超过8万人的队列研究[33]则提示加工肉类制品的摄入量与结直肠癌风险无关,但红肉的高摄入量与女性结肠癌风险升高相关;肉类摄入总量与男性结肠癌风险呈正相关趋势,但差异无统计学意义。一项meta分析[34]纳入了日本的6项队列研究和13项病例对照研究,结果提示红肉摄入量最高组与最低组的结直肠癌和结肠癌的RR分别为1.16(95% CI: 1.001~1.34)和1.21(95% CI: 1.03~1.43);加工肉类制品摄入量最高组与最低组的结直肠癌和结肠癌的RR分别为1.17(95% CI: 1.02~1.35)和1.23(95% CI: 1.03~1.47)。

我国的一项病例对照研究[35]共纳入265例结直肠癌患者和252例对照病例,发现红肉和家禽类肉制品的摄入量与结直肠癌发病无明显关系。邵红梅等[36]对中国人群结直肠癌危险因素的相关病例对照研究进行了汇总,通过对6 646例结直肠癌患者和9 957例对照者资料进行meta分析,发现红肉是结直肠癌发病的危险因素(OR=1.62, 95% CI: 1.27~2.07)。

第3条 长期吸烟是结直肠癌发病的高危因素

证据等级:Ⅱa

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:97.06%

吸烟是结直肠癌发病的重要危险因素,且与吸烟年限和总量有一定的剂量-效应关系。一项meta分析[37]发现,与不吸烟者相比,有吸烟史人群的结直肠癌RR为1.18(95% CI: 1.11~1.25),吸烟者较不吸烟者每10 000人中结直肠癌发病例数多出10.8例(95% CI: 7.9~13.6);吸烟量每增加10支/d可使结直肠癌风险升高7.8%,吸烟量每增加10年包(年包:数值=吸烟量×吸烟年数)则可使结直肠癌风险升高4.4%。此外,在吸烟史超过10年的人群中结直肠癌风险随吸烟史的延长而有升高的趋势,这种差异在吸烟史超过30年的人群中具有统计学意义[37]。另一项较大规模的meta分析[38]亦得出相似结论,即吸烟可增加约20%的结直肠癌风险。吸烟与不同部位肿瘤的相关性不尽一致,大部分研究提示吸烟与直肠癌风险的相关性强于与结肠癌的相关性[37,39-41]。同时,有研究表明在结直肠癌中,吸烟与远端结肠癌的相关性更为显著[41]。吸烟与不同性别人群结直肠癌风险的相关性有待进一步商榷,但有研究[40]表明吸烟与结直肠癌风险的相关性在男性人群中更为显著。吸烟与结直肠癌死亡率亦有显著相关性。与不吸烟的结直肠癌患者相比,现行吸烟的结直肠癌患者死亡风险上升1.26倍,具有既往吸烟史的患者死亡率升高1.11倍[42]。据估计,吸烟者较不吸烟者每10 000人中结直肠癌死亡例数多出6例(95% CI: 4.2~7.6)[37]。吸烟与p53、BRAF等基因的突变有一定的相关性,但与KRAS、APC等基因的突变无明显相关性,这可能在一定程度上提示了吸烟影响结直肠癌发生、发展的作用机制[43-44]。

第4条 长期大量饮酒是结直肠癌发病的高危因素

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:100%

乙醇摄入量与结直肠肿瘤的发病风险具有一定的相关性。Huxley等[38]对结直肠癌相关的危险因素进行了系统分析,通过回顾103项队列研究的数据发现,乙醇摄入量最高组的结直肠癌发病风险较对照组升高60%(RR=1.56, 95% CI: 1.42~1.70)。Bagnardi等[45]对1966—2000年的部分文献进行分析,发现与对照组相比,饮酒人群结直肠癌的相对风险随着饮酒量的升高而呈上升趋势(25 g/d:RR=1.08, 95% CI: 1.06~1.10;50 g/d:RR=1.18, 95% CI: 1.14~1.22;100 g/d:RR=1.38, 95% CI: 1.29~1.49)。尽管对重度饮酒量或频次的区分标准不尽相同,但各研究结论基本一致,即随着饮酒量或频次的升高,结直肠癌风险随之升高[46-51]。最新一项meta分析[52]结果显示结直肠癌的RR与饮酒量间存在线性正相关,进一步证实了上述观点。但饮酒量与结直肠癌风险相关性的程度在不同国家地区有所差异。日本的队列研究[53]按乙醇摄入量将饮酒人群分为四组,发现乙醇摄入量越高,结直肠癌的HR增加越明显(23~45.9 g/d:HR=1.42, 95% CI: 1.21~1.66;46~68.9 g/d:HR=1.95, 95% CI: 1.53~2.49;69~91.9 g/d:HR=2.15, 95% CI: 1.74~2.64;≥92 g/d: HR=2.96, 95% CI: 2.27~3.86),程度显著强于欧美地区相关的研究结果。然而,我国的研究结果似乎有所不同。一项meta分析[54]发现我国人群乙醇摄入量与结直肠癌发病并无明显相关性。邵红梅等[36]亦报道,饮酒组与对照组相比结直肠癌的OR为1.17(95% CI: 0.98~1.40)。

第5条 肥胖是结直肠癌发病的潜在高危因素

证据等级:Ⅱa

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:84.21%

肥胖是结直肠癌,尤其是结肠癌发病的高危因素。有研究[55]对2014年前的50项前瞻性研究进行分析,发现成人体重每增加5 kg可导致结肠癌等多种恶性肿瘤的发病风险升高。EPIC研究[56]行多因素分析发现,20~50岁组的成人每年体重每增加1 kg,其结肠癌的发病风险提高60%。Dai等[57]对2007年前发表的队列研究行meta分析,发现男性肥胖者结直肠癌风险较对照组显著升高(RR=1.37,95% CI: 1.21~1.56),女性肥胖者结直肠癌的RR为1.07(95% CI: 0.97~1.18);腰围与结肠癌的发病密切相关(男性RR=1.68,95% CI: 1.36~2.08;女性RR=1.48,95% CI: 1.19~1.84),而与直肠癌无明显关系(男性RR=1.26,95% CI: 0.90~1.77;女性RR=1.23,95% CI: 0.81~1.86)。Ma等[58]对41项涉及BMI和13项涉及中心型肥胖的研究进行分析,结果发现肥胖者结直肠癌发病风险为BMI正常者的1.334倍(95% CI: 1.253~1.420),腰围长度最长的1/4人群结直肠癌风险为腰围最短的1/4人群的1.455倍(95% CI: 1.327~1.596)。Larsson等[59]通过回顾性分析既往前瞻性研究亦得出了类似的结论。一项日本的研究[60]显示,BMI的升高与结直肠癌发病风险呈正相关。上述研究结果提示肥胖与结直肠癌的关系是多地区多种族的普遍现象。此外,一项meta分析[61]表明BMI每增长5 kg/m2可使结直肠腺瘤风险提高约20%,且该结果与研究纳入的受试者种族差异、地域分布、研究设计、性别等均无明确相关性。由于结直肠腺瘤是结直肠癌的高危因素,因此该研究提示肥胖可能参与了腺瘤向癌演变的全过程。

第6条 合理的体育锻炼可降低结直肠癌的患病风险

证据等级:Ⅱa

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:84.21%

合理的运动可在一定程度上降低结直肠癌的发病风险。EPIC等研究[62-63]已明确提示体力活动可显著降低结直肠癌风险,日本的研究[64]亦得出类似的结论。一项纳入19项队列研究的meta分析[65]发现职业性或娱乐性体力活动均可降低结直肠癌风险(职业性活动:RR=0.79,95% CI: 0.72~0.87;娱乐性活动:RR=0.78,95% CI: 0.68~0.91)。Wolin等[66]对52项队列或病例对照研究进行综合分析,发现活动量最高组人群较对照组人群的结肠癌RR为0.76(95% CI: 0.72~0.81),且这种负相关性在病例对照研究中更为明确(RR=0.69, 95% CI: 0.65~0.74)。Boyle等[67]对21项队列研究和病例对照研究行meta分析,发现活动量最高组人群与活动量最低组相比,近端结肠癌发病风险降低27%,远端结肠癌发病风险降低26%。另一项meta分析[68]提示活动量最高组与对照组相比,近端结肠癌的RR为0.76(95% CI: 0.70~0.83),远端结肠癌RR为0.77(95% CI: 0.71~0.83)。Liu等[69]对126项研究进行综合分析发现,世界卫生组织推荐的每日运动量可使结直肠癌的风险降低7%左右,而活动量超过推荐量两倍以上则出现饱和效应,提示合理的运动可有效减低结直肠癌风险。

第7条 结直肠腺瘤筛查可发现结直肠肿瘤的高危人群,降低结直肠癌的发病率

证据等级:Ⅰ

推荐等级:A

条款同意率:100%

具体方法见《中国早期结直肠癌及癌前病变筛查与诊治共识意见(2014年11月·重庆)》[7]的陈述。

第8条 阿司匹林、COX-2抑制剂等NSAIDs可减少结直肠腺瘤初发(Ⅱa),但存在潜在的不良反应(Ⅰ)

证据等级:Ⅱa

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:96.88%

大量的研究支持阿司匹林能有效预防结直肠癌。目前仅1项中等质量的随机对照试验[70]报道,低剂量阿司匹林(325 mg,qod. po.)服用5年未能减少平均危险度的男性结直肠腺瘤的发生。另有2项优质的队列研究[71-72]报道了一般危险度人群服用阿司匹林与腺瘤发生的关系,发现规律服用阿司匹林可使结直肠腺瘤的发生率降低28%,即服用 6~14片(每片325 mg)/周,其RR为0.68(95% CI: 0.55~0.84);而服用>14片/周,其RR为0.57(95% CI: 0.42~0.77)。综合分析5项病例对照研究[73-77]发现,规律服用阿司匹林持续3~10年可明显降低一般危险度人群结直肠腺瘤的发生。

目前尚无随机对照试验或队列研究证实其他非选择性NSAIDs和COX-2抑制剂在一般危险度人群中是否可减少结直肠腺瘤的发生,仅有8项病例对照研究[74-76,78-82]提示,规律服用NSAIDs可显著降低一般危险度人群结直肠腺瘤的发生(非阿司匹林NSAIDs:RR=0.54,95% CI: 0.4~0.74;任何NSAIDs:RR=0.57, 95% CI: 0.46~0.71)。

鉴于阿司匹林以及其他非选择性NSAIDs或COX-2抑制剂相关的消化性溃疡和心血管的不良反应[83-84],以及预防剂量、年限、起始年龄尚未阐明,考虑到长期使用的获益-风险比以及成本-效益比,目前并不支持其用于一般人群结直肠腺瘤初发的预防。

第9条 叶酸干预可预防散发性结直肠腺瘤的发生

证据等级:Ⅱa

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:84.21%

我国的一项前瞻性随机对照多中心临床干预试验[85]纳入960例>50岁、结肠镜排除新生物且血浆叶酸水平≤20 ng/mL的患者,随机分为2组:叶酸组以1 mg/d叶酸干预,对照组仅服用其他维生素。干预3年最终791例完成随访。叶酸组384例,发现结直肠腺瘤者64例,其中进展性腺瘤者8例,无腺瘤者320例;对照组407例,发现腺瘤者132例,其中进展性腺瘤者22例,无腺瘤者275例;组间差异有统计学意义(P<0.01)。表明叶酸干预可预防散发性结直肠腺瘤尤其是进展性腺瘤的发生。叶酸干预组中未发生结直肠腺瘤者的血浆叶酸浓度上升幅度明显大于发生结直肠腺瘤者。基础叶酸值低于4.27 ng/mL者补充叶酸后需血浓度上升较大幅度才可预防结直肠腺瘤初发,而基础叶酸值高于4.27 ng/mL者叶酸浓度有一定上升即可预防结直肠腺瘤的发生。

第10条 维生素D的摄入和循环25(OH)D水平在一定程度上与结直肠腺瘤的发生呈负相关

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:84.61%

越来越多的证据显示足够水平的维生素D对结直肠癌和结直肠腺瘤的发生有保护作用[86-87]。两项队列研究[81,88]发现高维生素D摄入与罹患结直肠腺瘤呈负相关,即总维生素D摄入可轻度降低结直肠腺瘤的发生(RR=0.79,95% CI: 0.63~0.99,P=0.07),但可显著降低远端结直肠腺瘤的风险(RR=0.67,95% CI: 0.52~0.87,P=0.004)。

循环25(OH)D水平与结直肠腺瘤发生风险亦呈负相关[89-92],且低水平血清25(OH)D可增加进展性结直肠腺瘤的风险[93]。

第11条 其他饮食来源的抗氧化类维生素预防结直肠腺瘤初发的作用尚需进一步大规模临床研究验证

证据等级:Ⅱc

推荐等级:C

条款同意率:89.48%

许多流行病学研究调查了维生素A、C和E与结直肠腺瘤发生的风险,但结果并不一致。一些研究[94-95]认为两者呈负相关,而另一些研究未发现两者有统计学联系[96-99]甚至是相反的结果[100]。最近一项纳入13项观察性流行病学研究共3 832例结直肠腺瘤患者的meta分析[101]显示,饮食来源的维生素C可降低结直肠腺瘤的发生风险(RR=0.78,95% CI: 0.62~0.98),β-胡萝卜素亦与结直肠腺瘤的发生呈负相关(RR=0.47,95% CI: 0.24~0.91)。然而,维生素A和E的摄入与结直肠腺瘤的发生无相关性(维生素A:RR=0.87,95% CI: 0.67~1.14;维生素E:RR=0.87,95% CI: 0.69~1.10)。仍需大型随机对照试验进一步验证。

二、散发性结直肠腺瘤的二级预防

第12条 结直肠腺瘤摘除可明显降低结直肠癌的发病率,但摘除后再发率较高

证据等级:Ⅰ

推荐等级:A

条款同意率:100%

早在1993年,Winawer等[3]对1 418例完成结肠镜检查者随访5.9年,认为内镜下摘除结直肠腺瘤并行内镜监测随访可降低75%以上结直肠癌的发生。腺瘤摘除后再发包括局部复发和非原处再发,前者的发生率并不高,EMR或电凝切除1年后,6.8%(55/808)出现原处复发;ESD切除1年后仅1.4%(10/716)出现原处复发[102]。而关于全部再发者,Martínez等[4]调查了9 167例结直肠腺瘤切除后患者,平均随访4年发现46.7%的患者又出现结直肠腺瘤,11.2%为进展性结直肠腺瘤,且0.6%演变为结直肠癌。某些结直肠腺瘤摘除后3年的再发率高达40%~50%[5]。一项我国5个医疗中心的研究[6]表明,进展性结直肠腺瘤摘除后1年的再发率高达59.46%,5年为78.07%。该再发情况主要因为腺瘤的异时性,上次检查的遗漏或切除不完全并非常见。同时,早期内镜下准确评估和采取合适的摘除方法至关重要。由解放军总医院等承担的“结直肠癌早期病变规范化研究”项目发现,结直肠癌早期病变内镜下评估首选窄带成像放大内镜,与术后病理诊断的符合率高于活检符合率。

第13条 改善生活习惯和调整饮食结构可能降低腺瘤摘除后的再发率

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:94.87%

具体方法见本共识条款第1~6条的陈述。

第14条 阿司匹林和COX-2抑制剂等NSAIDs具有减少腺瘤再发的作用

证据等级:Ⅰ

推荐等级:A

条款同意率:94.87%

大多数有关阿司匹林和COX-2抑制剂等NSAIDs的临床干预研究并未区分是针对腺瘤的一级(预防腺瘤初次发生)或二级(预防腺瘤摘除后再发)预防[103-104];但临床试验和流行病学研究提示,规律服用阿司匹林可减少腺瘤再发、降低结直肠肿瘤的发生率和死亡率[8,105]。

日本一项研究[106]给予152例结肠镜下摘除腺瘤(或腺癌)的患者100 mg阿司匹林干预(751±67) d,结果显示阿司匹林组再发肿瘤者36.8%(56/152),安慰剂组为45.9%(73/159);服用阿司匹林同时有吸烟嗜好者肿瘤再发率增至对照组的3.45倍,而不吸烟者肿瘤再发率减少至对照组的37%。对于有结直肠腺瘤或腺癌史的人群,服用不同剂量阿司匹林(81~325 mg/d)均可明显降低腺瘤的再发[107];而规律服用阿司匹林可使结直肠腺瘤再发率降低21%,进展性腺瘤再发率降低37%[105]。

三项COX-2抑制剂预防作用的大样本随机对照研究(分别为塞来昔布预防腺瘤的APC研究、预防结直肠散发腺瘤性息肉的PreSAP研究和罗非昔布预防腺瘤性息肉的APPROVe研究)明确指出,塞来昔布和罗非昔布可明显降低散发性结直肠腺瘤的再发率[108-111]。

第15条 阿司匹林、COX-2抑制剂等NSAIDs在发挥预防作用的同时,具有一定的不良反应

证据等级:Ⅰ

推荐等级:A

条款同意率:100%

考虑到NSAIDs的心血管和胃肠道出血等不良反应,究竟是低剂量50~160 mg/d,还是高剂量300~325 mg/d可达到理想效应,目前仍存在争议。但学者们认为服用阿司匹林预防结直肠癌至少应持续6年,且每周14片(325 mg/片)以上者效果较佳[112]。因此,需认真考虑长期服用该剂量的潜在危害,并审慎考虑不良反应和费用-疗效比[113]。

COX-2抑制剂塞来昔布已被美国FDA批准用于预防家族性腺瘤性息肉病(FAP)患者腺瘤的发生[114]。但有报道称,每日400 mg或800 mg塞来昔布组心血管疾病、心肌梗死、中风或心衰引起的死亡率为安慰剂组的2.3倍(95% CI: 0.9~5.5,P=0.06)或3.4倍(95% CI: 1.4~7.8,P=0.009)[115]。

第16条 钙剂具有减少结直肠腺瘤再发的作用

证据等级:Ⅰ

推荐等级:A

条款同意率:90.00%

一项研究[116]显示3 g/d碳酸钙(409例)可减少结肠镜下结直肠腺瘤摘除4年后的再发率至安慰剂对照(423例)的85%,即服用钙剂者127例发现了腺瘤,而对照组为159例。在一项以腺瘤再发为终点的临床试验[117]中,与安慰剂相比,每天补充1 200 mg钙,随访4年,腺瘤再发率显著降低,对进展性腺瘤的作用尤其明显,且终止补钙5年后,该预防作用仍持续存在。但研究[117-118]发现,钙对结直肠腺瘤再发的预防作用仅存在于维生素D水平较高的患者。

第17条 维生素D对结直肠腺瘤的再发有一定的预防作用;联合应用钙剂和维生素D预防结直肠腺瘤再发的作用更明显

证据等级:Ⅱa

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:100%

维生素D并非真正意义上的维生素,其是类固醇激素骨化三醇(即1,25二羟维生素D3)的前体,而骨化三醇具有广泛的生物学功能,能影响肿瘤的发生、发展[86]。血清25(OH)D水平与结直肠癌的发生率呈反比[119]。一项随机对照试验[120]证实,同时补充钙剂和维生素D较单独补充钙剂预防多种肿瘤的效果更佳,与对照组相比,单独补充钙剂者罹患肿瘤的RR为0.532(95% CI: 0.27~1.03,P=0.063),同时补充钙剂和维生素D的RR为0.402(95% CI: 0.20~0.82,P=0.013)。

美国一项多中心前瞻性、干预4年的研究[121]表明,应用钙剂(398例每天服用3 g碳酸钙或1 200 mg元素钙,405例服用安慰剂作为对照)可预防结直肠腺瘤再发,但血液中25(OH)D水平不能低于平均值(29.1 ng/mL);另一方面,在补充钙剂的人群中,25(OH)D水平与腺瘤再发率呈负相关。进一步提示补充钙剂和维持高水平维生素D有利于降低腺瘤的再发。

然而,Baron等[122]的前瞻性双盲多中心干预研究显示,每天补充维生素D3 1 000 IU、钙剂1 200 mg或联合补充两者3~5年,均不能降低结直肠腺瘤的再发。但该研究结果受到其他学者的多方质疑,主要问题可能为该研究干预时间较短、应重点观察高危腺瘤、受到其他来自食物营养素的干扰,或钙与维生素D联合预防结直肠腺瘤初发的效果可能更好[123]。

第18条 对于腺瘤再发的预防,叶酸的作用尚未定论

证据等级:Ⅰ

推荐等级:A

条款同意率:93.94%

叶酸可预防腺瘤的初次发生(一级预防),但其预防腺瘤摘除后再发的作用尚未定论。一项英国的结直肠腺瘤预防的多中心、随机双盲研究[106]评估了补充叶酸(0.5 mg/d)对结直肠腺瘤再发的预防作用。腺瘤≥0.5 cm的患者在入组前6个月内接受腺瘤切除,3年后90.3%的患者接受了第二次结肠镜检查。结果发现补充叶酸并不能降低结直肠腺瘤再发危险。一项多中心临床试验[124]将1 021例结直肠腺瘤患者分成两组,516例以1 mg/d叶酸干预,505例服用安慰剂。结果显示3年和5年随访均未发现叶酸具有预防腺瘤摘除后再发的作用,甚至叶酸干预者进展性腺瘤发生率高于对照组(11.6%对6.9%)。但另一项研究[125]发现,对于血浆叶酸浓度≤7.5 ng/mL的结直肠腺瘤(至少一个腺瘤)患者,补充叶酸可减少低叶酸者结直肠腺瘤的再发率。

补充叶酸抑制结直肠癌的发生可能取决于使用时患者所处的结直肠肿瘤不同时期,对正常结直肠黏膜起保护作用而对已出现病变的部位无保护作用。叶酸可预防原发腺瘤的生成,但不一定预防腺瘤再发或复发。预防作用可能仅发生在叶酸基础水平较低者。补充叶酸可能在癌前疾病阶段前发挥预防作用,而一旦进入这个阶段,如腺瘤性息肉,其预防作用则尚不明确。摄入叶酸的剂量、叶酸干预时间以及干预时间点的选择、基础血浆叶酸浓度和乙醇摄入等因素均可影响叶酸对结直肠肿瘤的预防作用,因此叶酸应用的剂量大小、时间长短、应用时期的确定以及有无其他因素干扰(如乙醇)至关重要,需进一步探索。

第19条 二甲双胍可能具有预防腺瘤再发的作用,需更多研究证实

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:C

条款同意率:80.00%

二甲双胍具有较广泛的抗肿瘤作用。新近日本一项研究[126]以二甲双胍250 mg/d(71例)干预1年,62例给予安慰剂作为对照。结果发现二甲双胍组再发腺瘤者22例,安慰剂组为32例,组间差异有统计学意义(RR=0.60, 95% CI: 0.39~0.92,P=0.016)。且观察过程中未发现该药的明显不良反应。但仍需进一步研究验证。

第20条 来源于天然植物的药物和调节肠道微生态预防结直肠腺瘤再发的作用值得深入研究

证据等级:Ⅲ

推荐等级:C

条款同意率:96.15%

包括姜黄素等来源于天然植物的药物可降低结直肠肿瘤的发生,但其对腺瘤摘除后再发的影响尚未明了[127]。

肠道微生态和肠道免疫决定肠道稳态,在某种程度上代表结直肠的环境因素,影响结直肠癌的发生、发展。肠道菌群失调、胆汁酸代谢异常与结直肠癌的发生、发展以及治疗等密切相关。现已发现与结直肠癌发生相关的可能病原菌主要包括具核梭杆菌、致病性大肠杆菌、产毒性脆弱拟杆菌等[128]。有研究提出可通过调节肠道菌群而影响和预防结直肠肿瘤的发生、发展[129]。如能阐明肠道不同菌群通过胆汁酸代谢的致瘤作用和机制,将有利于针对不同菌群研究益生菌,提供微生态制剂,对于阐明结直肠癌的发病机制及其预防起有重要作用。

三、IBD相关性结直肠癌的预防

第21条 UC是结直肠癌的癌前疾病,尤其是病程超过10年、全结直肠病变以及反复炎症的患者(B级);应重视对IBD患者的定期内镜筛查(A级)

证据等级:Ⅱa

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:100%

IBD是结直肠癌的癌前疾病,其中以UC的关系更为密切。一项基于人群队列研究的meta分析[130]表明,UC患者的结直肠癌发生率为1.6%,病程少于10年者<1.0%,15年者为0.4%~2.0%,20年者为1.1%~5.3%,结直肠癌在UC患者中的发病率较正常人群高2.4倍。

病变范围是UC患者发生结直肠癌的另一高危因素。广泛性或全结肠型UC癌变的风险最高,为正常人群的15倍,左半结肠炎癌变风险较低,仅为2.8倍。病变部位与肿瘤发生关系的强度依次为全结肠、左半结肠、直肠型和非结肠型克罗恩病(Crohn’s disease, CD),结直肠癌发生的RR分别为2.0、1.2、0.9和0.7[131]。关于CD相关性结直肠癌的问题目前尚在研究中,Jess等[132]基于人群的研究发现,长期CD患者的结直肠癌发生风险并未增加,尤其是仅局限于小肠的CD患者。

反复炎症是UC相关性结直肠癌发生的基础。一项病例对照研究[133]发现,有效的抗炎治疗可预防肿瘤的发生,与吸烟、原发性硬化性胆管炎(PSC)和肿瘤家族史相比,炎症是肿瘤发生的独立危险因素。

定期结肠镜检查是筛查IBD发生癌变的有效方法。通过对IBD患者进行定期结肠镜检查,可及早发现上皮内瘤变或早期病变,及时给予相应处理,有效降低癌变的发病率和死亡率[134]。一项回顾性研究[135]发现,所有IBD患者均应在病情控制后行结肠镜检查,并在发病8~10年后行常规结肠镜筛查预防癌变发生,左半结肠炎患者在发病15~20年后应开始行规律筛查,建议每2年行结肠镜检查。

目前采用常规全结肠镜检查,推荐每隔10 cm的四点活检法行病变筛查,但这一方法在临床上不易开展。随着内镜技术的发展,近来多项研究发现采用亚甲蓝或靛胭脂的染色内镜有益于发现IBD相关性结直肠癌,结直肠上皮内瘤变的检出率较常规结肠镜提高4~5倍,因此目前多项指南建议采用全结肠染色内镜结合可疑部位的定向活检方法对IBD患者进行筛查,以取代常规的结肠镜多点活检法[136]。对于内镜下发现的任何级别上皮内瘤变,需行内镜下治疗,并根据最终的病理结果密切随诊或行手术治疗[137]。

第22条 5-氨基水杨酸(5-aminosalicylic acid, 5-ASA)仅在UC炎症控制和延长缓解期时应用有预防癌变的作用,在CD中的作用尚未明确

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:97.44%

反复炎症反应是UC癌变的病理基础,在这一过程中许多炎症因子,如IL-6、TNF-α起有重要作用。因此控制炎症反应、维持病变缓解在预防肿瘤发生方面具有重要作用。5-ASA作为治疗轻中度UC的一线药物,在控制炎症反应和维持缓解方面具有重要作用。多项研究[138-140]表明5-ASA具有预防UC癌变的作用,但近来一项meta分析[141]发现5-ASA并不能预防IBD患者发生结直肠癌,这可能与该研究中纳入了CD患者有关。5-ASA在CD患者中诱导和维持炎症缓解的作用尚不明确[142]。一项meta分析[143]纳入了17项研究共20 193例UC患者,发现5-ASA可降低结直肠癌和上皮内瘤变的发生率(OR=0.63,95% CI: 0.48~0.84)。5-ASA起保护作用的平均剂量应>2.0 g/d。

第23条 硫唑嘌呤能提高黏膜愈合质量,可能具有一定预防IBD癌变的作用

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:80.00%

IBD治疗中常用的免疫抑制剂包括硫唑嘌呤、6-巯基嘌呤(6-MP)、甲氨蝶呤、环磷酰胺(CTX)等。免疫抑制剂的应用对控制炎症、维持缓解和黏膜愈合有重要作用。一项大规模的基于人群的队列研究[144]发现,硫唑嘌呤能明显减少IBD患者发生高级别上皮内瘤变和结直肠癌的风险(HR=0.10,95% CI: 0.01~0.75)。前瞻性流行病学研究[145]发现,19 486例IBD队列人群中0.3%的患者在随诊期间检出高级别上皮内瘤变或结直肠癌;对于病程超过10年,或全结肠重度病变者,硫唑嘌呤维持治疗发生癌变的HR仅为0.28(95% CI: 0.1~0.9,P=0.03)。一项纳入19项研究的meta分析[146]中,其中9项为病例对照研究,10项为人群队列研究,结果发现校正病程和病变部位后,硫唑嘌呤可明显降低结直肠癌、高级别上皮内瘤变和低级别上皮内瘤变的发生(RR=0.71,95% CI: 0.54~0.94,P=0.017)。

其他免疫抑制剂预防IBD癌变的临床研究相对较少,有待进一步观察。

第24条 PSC是IBD癌变的独立危险因素,但目前不推荐使用熊去氧胆酸(UDCA)预防IBD癌变

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:84.62%

PSC是IBD发生癌变的重要危险因素,但不同地区有所差异[147]。我国的初步研究未发现PSC与IBD癌变之间的关系,可能与我国PSC发病率较低有关[148]。UDCA作为治疗PSC的药物,在预防IBD发生中的作用有限。一项长期随机安慰剂对照研究[149]发现,在超过10年的随访期间,UDCA治疗组与安慰剂组之间IBD-PSC发生癌变的情况无明显差异(13%对16%)。纳入763例PSC-IBD患者的meta分析[150-151]表明,发生结直肠癌的患者共177例,癌变率明显高于不合并PSC的IBD患者,UDCA并没有明显预防癌变的作用(OR=0.81, 95% CI: 0.41~1.61)。

第25条 微生态制剂在预防IBD癌变中的作用有待进一步研究

证据等级:Ⅲ

推荐等级:C

条款同意率:85.71%

微生态制剂对缓解UC炎症反应有一定疗效,其中双歧杆菌、乳酸杆菌治疗轻中度UC有一定疗效。单中心临床随机双盲研究[152-153]发现VSL#3复合微生态制剂对缓解轻中度UC患者的炎症有一定疗效。77例UC患者服用VSL#3,70例服用安慰剂,共观察6周,发现25例(32.5%)使用VSL#3者和7例(10%)使用安慰剂者UCDAI评分降低。目前相关研究结果均为益生菌与其他药物联合应用可延长病情缓解时间。有关益生菌预防IBD癌变的研究现多为动物实验,尚缺乏临床研究。

第26条 全结直肠切除适用于癌变、伴有高级别上皮内瘤变者;伴低级别上皮内瘤变的患者推荐内镜监测

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:88.57%

根据最新的meta分析,近年随着IBD治疗的规范、炎症控制和维持缓解的治疗效果较好,IBD发生癌变的比例呈下降趋势[154],因此不推荐采用全结肠切除的方法预防IBD癌变。但对于一些特殊人群,如药物对炎症控制不满意、病变反复发作、发现高级别上皮内瘤变或结直肠癌,则建议全结肠切除。一项单中心研究[155]发现,123例患者中,31.7%的患者因癌变行全结肠切除,55.3%因病情反复;在手术患者中,10例(8.1%)患者仅在术后发现上皮内瘤变,其中2例为高级别上皮内瘤变,1例为结直肠癌。因此,由于IBD癌变的表现形态缺乏特异性、肿瘤有异质性特点,若结肠镜筛查发现高级别上皮内瘤变或结直肠癌,建议行全结肠切除[156]。近来有指南[134]推荐对于非息肉样异型增生病灶内镜下切除后可行内镜随诊,不必行全结肠切除。

四、家族性结直肠肿瘤的预防

第27条 林奇综合征(Lynch syndrome)等家族性结直肠肿瘤患者及其家系成员应行遗传学检测;林奇综合征患者、突变携带者以及未行基因检测的家系成员,应接受结肠镜随访和肠外肿瘤监测;结肠镜检查并内镜下切除息肉可降低林奇综合征患者因结直肠癌死亡的风险[157]

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:91.18%

林奇综合征又称为遗传性非息肉病性结直肠癌(hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, HNPCC),是最常见的遗传性结直肠癌综合征,占所有结直肠癌患者的2%~3%,为常染色体显性遗传疾病[158-161],由DNA错配修复基因(MLH1、MSH2、MSH6、PMS2)或上皮细胞黏附分子EPCAM胚系突变所致[157,162-167]。高度怀疑林奇综合征时应行MLH1、MSH2、MSH6、PMS2和(或)EPCAM基因胚系突变检测,检测流程见图1。

MLH1、MSH2、EPCAM突变携带者患结直肠癌的风险更高[157,162-165,167],MSH6或PMS2突变携带者的风险相对较低[168-169]。因此,针对MLH1、MSH2、EPCAM突变携带者结直肠癌的监测,推荐20~25岁开始行结肠镜随访。若家系中最早的发病年龄<25岁则先于该年龄的2~5年开始进行随访,每1~2年复查。MSH6或PMS2突变携带者结直肠癌监测方案:推荐25~30岁开始进行结肠镜随访。若家系中最早的发病年龄<30岁则先于该年龄的2~5年开始,每1~2年复查[170-171]。家系中未行基因检测的成员随访策略与突变携带者的随访策略相同。经基因检测未发现突变的家系成员则按一般风险人群进行随访。

据国外报道[172-178]称,林奇综合征并发的肠外肿瘤中,子宫内膜癌和卵巢癌较为多见,可于30~35岁开始每年一次行妇科检查。而我国林奇综合征患者肠外肿瘤以胃癌多见,子宫内膜癌发生率略低于胃癌[179]。因此国内推荐林奇综合征患者自30~35岁起每3~5年行胃镜检查[180-182]。

第28条 结肠切除术是林奇综合征患者基本的治疗方式,结肠部分切除术后患者仍应每1~2年进行一次结肠镜随访

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:90.48%

当结肠镜下无法切除息肉或肿瘤时应行手术治疗。对于>60~65岁或有潜在的括约肌功能障碍者可考虑行结肠次全切除术[171,183]。林奇综合征患者因结直肠癌行结肠部分切除术后,剩余结肠或直肠约19%于10年后、47%于20年后、69%于30年后癌症再发[184],因此,林奇综合征患者结直肠部分切除术后的再发率高,应对剩余结肠或直肠每1~2年行结肠镜或乙状结肠镜检查,随访策略同林奇综合征致病基因携带者。

第29条 对以下可疑为腺瘤性息肉综合征的患者建议行相关基因检测,主要筛查基因为APC和MUTYH:①结直肠腺瘤性息肉超过10枚;②有腺瘤性息肉综合征家族史;③结直肠腺瘤患者,且有FAP相关肠外表现

证据等级:Ⅲ

推荐等级:C

条款同意率:94.74%

腺瘤性息肉综合征包括经典型家族性腺瘤性息肉病(CFAP)、衰减型家族性腺瘤性息肉病(AFAP)和MUTYH相关息肉病(MAP)。FAP患者APC基因的突变阳性检出率为70%~79%[185-186];而MAP是一种MUTYH基因突变所致的常染色体隐性遗传疾病,MUTYH基因阳性突变率最高为11%~12%[187]。欧洲报道欧美人群基因突变热点为Y179C、G396D、Y165C、G382D[187-188],而国内尚未见上述基因突变热点的报道。

对有明确突变患者的亲属行该突变位点的检测。APC基因检测结果为阴性时,应行MUTYH基因检测[189],MUTYH基因出现等位基因突变,或MUTYH基因两条链虽无等位基因突变,但均包含致病性突变时,则可确诊为MAP[190]。主要检测方式包括一代测序结合多重连接探针扩增技术(MLPA),或二代高通量测序。腺瘤性息肉综合征的基因筛查检测流程见图2。

第30条 从10~12岁开始,对FAP患者、突变携带者以及未行基因检测的家系成员每1~2年行一次结肠镜筛查

证据等级:Ⅱb

推荐等级:B

条款同意率:93.75%

有文献报道,FAP患者的最早发病年龄为6岁[191],大部分CFAP家系成员有致病性突变者通常于青春期发病,建议从 10~12岁开始每1~2年进行一次乙状结肠镜或结肠镜

LS:林奇综合征;IHC:免疫组化法;MSI:微卫星不稳定性

图2 腺瘤性息肉综合征的基因筛查流程图

筛查[190],一旦发现息肉,则每年一次全结肠镜检查,直至行结肠切除术。AFAP家系成员建议从18~20岁开始,每2年一次。

第31条 根据FAP患者年龄、息肉的负荷和患者情况综合考虑行结直肠切除的时间[192]

证据等级:Ⅲ

推荐等级:C

条款同意率:97.05%

目前对于预防性结直肠切除时间尚无定论,可根据FAP患者年龄、息肉的负荷和患者情况综合考虑行结直肠切除的时间[193]。发现结直肠癌或内镜下无法切除癌前病变者应立即行外科手术。

第32条 对FAP患者、突变携带者以及未行基因检测的家系成员的相关结直肠外肿瘤应从25~30岁开始随访

证据等级:Ⅲ

推荐等级:C

条款同意率:94.12%

对上消化道监测开始时间尚无定论,推荐从确定有结直肠息肉或20~25岁开始进行上消化道内镜监测,每3年一次[192]。内镜检查发现,约超过一半的FAP患者伴有十二指肠息肉,癌变的风险为3%~5%或更高[194-195]。根据Spigelman分级决定十二指肠镜的随访间隔时间。Spigelman评分标准如下:1分:息肉数目为1~4枚、大小为1~4 mm、病理为管状腺瘤伴低级别上皮内瘤变;2分:息肉数目为5~20枚、大小为5~10 mm或病理为绒毛管状腺瘤;3分:息肉数目>20枚、大小>10 mm、病理为绒毛管状腺瘤伴高级别上皮内瘤变,总分为每一项对应分数之和。Spigelman分级按照0分、1~4分、5~6分、7~8分和9~12分分为0~4级,随访时间间隔随着评分的增加而缩短,分别为4年、2~3年、1~3年、6~12个月和3~6个月[196-199]。约0.6%的FAP患者胃底腺息肉会发展成癌[200],当发现高级别上皮内瘤变或浸润癌时应行手术治疗。甲状腺的检查应从10岁起每年行一次甲状腺超声检查;对于携带基因突变的婴幼儿,建议从出生起每半年行甲胎蛋白检测和肝脏B超检查,直至7岁;腹内纤维瘤的检测应包括每年的腹壁触诊,如患者有相应症状或纤维瘤家族史,肠切除术后1~3年应行一次腹部MRI/CT检查,此后间隔5~10年复查,对于其他肠外器官目前尚无随访方案[201]。

总而言之,预防是有效管理和控制结直肠癌的关键。尽管目前可通过改善生活习惯、调节饮食结构、筛查、内镜下腺瘤摘除和定期随访以及化学药物降低结直肠癌的发生率,但实际上并非所有措施均能奏效。临床工作正期待着发现和开拓更适合于平均危险度和高危人群的不同预防策略。

共识意见执笔撰写者:

房静远 时永全 陈萦晅 李景南 盛剑秋

参与共识意见讨论和定稿者(按姓氏汉语拼音排序):

白飞虎 白文元 陈东风 陈红梅 陈旻湖 陈其奎

陈世耀 陈卫昌 陈萦晅 段丽平 樊代明 房殿春

房静远 冯 樱 高 峰 戈之铮 郭晓钟 韩 英

侯晓华 霍丽娟 姜海行 蒋明德 蓝 宇 李建生

李景南 李良平 李 岩 李延青 李兆申 林 琳

刘 杰 刘 诗 刘思德 刘新光 陆 伟 吕 宾

吕农华 罗和生 聂玉强 钱家鸣 任建林 沈 薇

沈锡中 盛剑秋 时永全 苏秉忠 唐承薇 田德安

田字彬 庹必光 王吉耀 王江滨 王良静 王巧民

王小众 王学红 韦 红 吴开春 吴小平 谢渭芬

许建明 许 乐 杨仕明 杨幼林 杨云生 游苏宁

袁伟建 袁耀宗 张 军 张澍田 张晓岚 张志广

郑鹏远 郑 勇 钟 捷 朱 萱 邹多武 邹晓平

1 Binefa G, Rodríguez-Moranta F, Teule A, et al. Colorectal cancer: from prevention to personalized medicine[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20 (22): 6786-6808.

2 Giovannucci E. Modifiable risk factors for colon cancer[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2002, 31 (4): 925-943.

3 Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup[J]. N Engl J Med, 1993, 329 (27): 1977-1981.

4 Martínez ME, Sampliner R, Marshall JR, et al. Adenoma characteristics as risk factors for recurrence of advanced adenomas[J]. Gastroenterology, 2001, 120 (5): 1077-1083.

5 Martínez ME, Baron JA, Lieberman DA, et al. A pooled analysis of advanced colorectal neoplasia diagnoses after colonoscopic polypectomy[J]. Gastroenterology, 2009, 136 (3): 832-841.

6 Gao QY, Chen HM, Sheng JQ, et al. The first year follow-up after colorectal adenoma polypectomy is important: a multiple-center study in symptomatic hospital-based individuals in China[J]. Front Med China, 2010, 4 (4): 436-442.

7 中华医学会消化内镜学分会消化系早癌内镜诊断与治疗协作组; 中华医学会消化病学分会消化道肿瘤协作组; 中华医学会消化内镜学分会肠道学组; 等. 中国早期结直肠癌及癌前病变筛查与诊治共识意见(2014年11月·重庆) [J]. 中华内科杂志, 2015, 54 (4): 375-389.

8 中华医学会消化病学分会. 中国结直肠肿瘤筛查、早诊早治和综合预防共识意见[J]. 中华消化杂志, 2012, 32 (1): 1-10; 2002, 32 (2): 73-81.

9 Sung JJ, Ng SC, Chan FK, et al; Asia Pacific Working Group. An updated Asia Pacific Consensus Recommendations on colorectal cancer screening[J]. Gut, 2015, 64 (1): 121-132.

10 Ben Q, Sun Y, Chai R, et al. Dietary fiber intake reduces risk for colorectal adenoma: a meta-analysis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2014, 146 (3): 689-699.

11 Trock B, Lanza E, Greenwald P. Dietary fiber, vegetables, and colon cancer: critical review and meta-analyses of the epidemiologic evidence[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 1990, 82 (8): 650-661.

12 Bingham SA, Day NE, Luben R, et al; European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Dietary fibre in food and protection against colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): an observational study[J]. Lancet, 2003, 361 (9368): 1496-1501.

13 Murphy N, Norat T, Ferrari P, et al. Dietary fibre intake and risks of cancers of the colon and rectum in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) [J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7 (6): e39361.

14 Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, et al. Dietary fiber and the risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma in women[J]. N Engl J Med, 1999, 340 (3): 169-176.

15 Park Y, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, et al. Dietary fiber intake and risk of colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies[J]. JAMA, 2005, 294 (22): 2849-2857.

16 Chen HM, Yu YN, Wang JL, et al. Decreased dietary fiber intake and structural alteration of gut microbiota in patients with advanced colorectal adenoma[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2013, 97 (5): 1044-1052.

17 Aune D, Lau R, Chan DS, et al. Nonlinear reduction in risk for colorectal cancer by fruit and vegetable intake based on meta-analysis of prospective studies[J]. Gastroenterology, 2011, 141 (1): 106-118.

18 Kashino I, Mizoue T, Tanaka K, et al; Research Group for Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan. Vegetable consumption and colorectal cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review and meta-analysis among the Japanese population[J]. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 2015, 45 (10): 973-979.

19 Leenders M, Siersema PD, Overvad K, et al. Subtypes of fruit and vegetables, variety in consumption and risk of colon and rectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition[J]. Int J Cancer, 2015, 137 (11): 2705-2714.

20 Koushik A, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, et al. Fruits, vegetables, and colon cancer risk in a pooled analysis of 14 cohort studies[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2007, 99 (19): 1471-1483.

21 Wu QJ, Yang Y, Vogtmann E, et al. Cruciferous vegetables intake and the risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. Ann Oncol, 2013, 24 (4): 1079-1087.

22 Tse G, Eslick GD. Cruciferous vegetables and risk of colorectal neoplasms: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Nutr Cancer, 2014, 66 (1): 128-139.

23 Larsson SC, Wolk A. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies[J]. Int J Cancer, 2006, 119 (11): 2657-2664.

24 Sandhu MS, White IR, McPherson K. Systematic review of the prospective cohort studies on meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analytical approach[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2001, 10 (5): 439-446.

25 Norat T, Lukanova A, Ferrari P, et al. Meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies[J]. Int J Cancer, 2002, 98 (2): 241-256.

26 Smolińska K, Paluszkiewicz P. Risk of colorectal cancer in relation to frequency and total amount of red meat consumption. Systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Arch Med Sci, 2010, 6 (4): 605-610.

27 Chan DS, Lau R, Aune D, et al. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: meta-analysis of prospective studies[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6 (6): e20456.

28 Bernstein AM, Song M, Zhang X, et al. Processed and unprocessed red meat and risk of colorectal cancer: Analysis by tumor location and modification by time[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10 (8): e0135959.

29 Carr PR, Walter V, Brenner H, et al. Meat subtypes and their association with colorectal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Int J Cancer, 2016, 138 (2): 293-302.

30 Lee SI, Moon HY, Kwak JM, et al. Relationship between meat and cereal consumption and colorectal cancer in Korea and Japan[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2008, 23 (1): 138-140.

31 Shin A, Joo J, Bak J, et al. Site-specific risk factors for colorectal cancer in a Korean population[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6 (8): e23196.

32 Oba S, Shimizu N, Nagata C, et al. The relationship between the consumption of meat, fat, and coffee and the risk of colon cancer: a prospective study in Japan[J]. Cancer Lett, 2006, 244 (2): 260-267.

33 Takachi R, Tsubono Y, Baba K, et al; Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study Group. Red meat intake may increase the risk of colon cancer in Japanese, a population with relatively low red meat consumption[J]. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr, 2011, 20 (4): 603-612.

34 Pham NM, Mizoue T, Tanaka K, et al; Research Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan. Meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence among the Japanese population[J]. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 2014, 44 (7): 641-650.

35 Song Y, Liu M, Yang FG, et al. Dietary fibre and the risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control study[J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2015, 16 (9): 3747-3752.

36 邵红梅, 冯瑞, 朱红, 等. 中国人群结直肠癌危险因素的meta分析[J]. 中国慢性病预防与控制, 2014, 22 (2): 174-177.

37 Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, et al. Smoking and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis[J]. JAMA, 2008, 300 (23): 2765-2778.

38 Huxley RR, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Clifton P, et al. The impact of dietary and lifestyle risk factors on risk of colorectal cancer: a quantitative overview of the epidemiological evidence[J]. Int J Cancer, 2009, 125 (1): 171-180.

39 Liang PS, Chen TY, Giovannucci E. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Int J Cancer, 2009, 124 (10): 2406-2415.

40 Tsoi KK, Pau CY, Wu WK, et al. Cigarette smoking and the risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009, 7 (6): 682-688. e1-e5.

41 Cheng J, Chen Y, Wang X, et al. Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies of cigarette smoking and the incidence of colon and rectal cancers[J]. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2015, 24 (1): 6-15.

42 Walter V, Jansen L, Hoffmeister M, et al. Smoking and survival of colorectal cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Ann Oncol, 2014, 25 (8): 1517-1525.

43 Chen K, Xia G, Zhang C, et al. Correlation between smoking history and molecular pathways in sporadic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis[J]. Int J Clin Exp Med, 2015, 8 (3): 3241-3457.

44 Porta M, Crous-Bou M, Wark PA, et al. Cigarette smoking and K-ras mutations in pancreas, lung and colorectal adenocarcinomas: etiopathogenic similarities, differences and paradoxes[J]. Mutat Res, 2009, 682 (2-3): 83-93.

45 Bagnardi V, Blangiardo M, La Vecchia C, et al. A meta-analysis of alcohol drinking and cancer risk[J]. Br J Cancer, 2001, 85 (11): 1700-1705.

46 Cho E, Smith-Warner SA, Ritz J, et al. Alcohol intake and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 8 cohort studies[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2004, 140 (8): 603-613.

47 Moskal A, Norat T, Ferrari P, et al. Alcohol intake and colorectal cancer risk: a dose-response meta-analysis of published cohort studies[J]. Int J Cancer, 2007, 120 (3): 664-671.

48 Fedirko V, Tramacere I, Bagnardi V, et al. Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies[J]. Ann Oncol, 2011, 22 (9): 1958-1972.

49 Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis[J]. Br J Cancer, 2015, 112 (3): 580-593.

50 Zhang C, Zhong M. Consumption of beer and colorectal cancer incidence: a meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. Cancer Causes Control, 2015, 26 (4): 549-560.

51 Wang Y, Duan H, Yang H, et al. A pooled analysis of alcohol intake and colorectal cancer[J]. Int J Clin Exp Med, 2015, 8 (5): 6878-6889.

52 Jayasekara H, MacInnis RJ, Room R, et al. Long-term alcohol consumption and breast, upper aero-digestive tract and colorectal cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Alcohol Alcohol, 2016, 51 (3): 315-330.

53 Mizoue T, Inoue M, Wakai K, et al; Research Group for Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan. Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer in Japanese: a pooled analysis of results from five cohort studies[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2008, 167 (12): 1397-1406.

54 Li Y, Yang H, Cao J. Association between alcohol consumption and cancers in the Chinese population -- a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6 (4): e18776.

55 Keum N, Greenwood DC, Lee DH, et al. Adult weight gain and adiposity-related cancers: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective observational studies[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2015, 107 (2): pii: djv088.

56 Aleksandrova K, Pischon T, Buijsse B, et al. Adult weight change and risk of colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2013, 49 (16): 3526-3536.

57 Dai Z, Xu YC, Niu L. Obesity and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of cohort studies[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2007, 13 (31): 4199-4206.

58 Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F, et al. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8 (1): e53916.

59 Larsson SC, Wolk A. Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2007, 86 (3): 556-565.

60 Matsuo K, Mizoue T, Tanaka K, et al; Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan. Association between body mass index and the colorectal cancer risk in Japan: pooled analysis of population-based cohort studies in Japan[J]. Ann Oncol, 2012, 23 (2): 479-490.

61 Ben Q, An W, Jiang Y, et al. Body mass index increases risk for colorectal adenomas based on meta-analysis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2012, 142 (4): 762-772.

62 Friedenreich C, Norat T, Steindorf K, et al. Physical activity and risk of colon and rectal cancers: the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2006, 15 (12): 2398-2407.

63 de Vries E, Soerjomataram I, Lemmens VE, et al. Lifestyle changes and reduction of colon cancer incidence in Europe: A scenario study of physical activity promotion and weight reduction[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2010, 46 (14): 2605-2616.

64 Pham NM, Mizoue T, Tanaka K, et al; Research Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan. Physical activity and colorectal cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence among the Japanese population[J]. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 2012, 42 (1): 2-13.

65 Samad AK, Taylor RS, Marshall T, et al. A meta-analysis of the association of physical activity with reduced risk of colorectal cancer[J]. Colorectal Dis, 2005, 7 (3): 204-213.

66 Wolin KY, Yan Y, Colditz GA, et al. Physical activity and colon cancer prevention: a meta-analysis[J]. Br J Cancer, 2009, 100 (4): 611-616.

67 Boyle T, Keegel T, Bull F, et al. Physical activity and risks of proximal and distal colon cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2012, 104 (20): 1548-1561.

68 Robsahm TE, Aagnes B, Hjartåker A, et al. Body mass index, physical activity, and colorectal cancer by anatomical subsites: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies[J]. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2013, 22 (6): 492-505.

69 Liu L, Shi Y, Li T, et al. Leisure time physical activity and cancer risk: evaluation of the WHO’s recommendation based on 126 high-quality epidemiological studies[J]. Br J Sports Med, 2016, 50 (6): 372-378.

70 Gann PH, Manson JE, Glynn RJ, et al. Low-dose aspirin and incidence of colorectal tumors in a randomized trial[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 1993, 85 (15): 1220-1224.

71 Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, et al. Aspirin use and the risk for colorectal cancer and adenoma in male health professionals[J]. Ann Intern Med, 1994, 121 (4): 241-246.

72 Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Schernhammer ES, et al. A prospective study of aspirin use and the risk for colorectal adenoma[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2004, 140 (3): 157-166.

73 Suh O, Mettlin C, Petrelli NJ. Aspirin use, cancer, and polyps of the large bowel[J]. Cancer, 1993, 72 (4): 1171-1177.

74 Logan RF, Little J, Hawtin PG, et al. Effect of aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on colorectal adenomas: case-control study of subjects participating in the Nottingham faecal occult blood screening programme[J]. BMJ, 1993, 307 (6899): 285-289.

75 Morimoto LM, Newcomb PA, Ulrich CM, et al. Risk factors for hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps: evidence for malignant potential? [J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2002, 11 (10 Pt 1): 1012-1018.

76 García Rodríguez LA, Huerta-Alvarez C. Reduced incidence of colorectal adenoma among long-term users of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: a pooled analysis of published studies and a new population-based study[J]. Epidemiology, 2000, 11 (4): 376-381.

77 Kahn HS, Tatham LM, Thun MJ, et al. Risk factors for self-reported colon polyps[J]. J Gen Intern Med, 1998, 13 (5): 303-310.

78 Hauret KG, Bostick RM, Matthews CE, et al. Physical activity and reduced risk of incident sporadic colorectal adenomas: observational support for mechanisms involving energy balance and inflammation modulation[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2004, 159 (10): 983-992.

79 Peleg II, Lubin MF, Cotsonis GA, et al. Long-term use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and other chemopreventors and risk of subsequent colorectal neoplasia[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 1996, 41 (7): 1319-1326.

80 Martínez ME, McPherson RS, Levin B, et al. Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of colorectal adenomatous polyps among endoscoped individuals[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 1995, 4 (7): 703-707.

81 Lieberman DA, Prindiville S, Weiss DG, et al; Cooperative Study Group 380. Risk factors for advanced colonic neoplasia and hyperplastic polyps in asymptomatic individuals[J]. JAMA, 2003, 290 (22): 2959-2967.

82 Martin C, Connelly A, Keku TO, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, apoptosis, and colorectal adenomas[J]. Gastroenterology, 2002, 123 (6): 1770-1777.

83 Massat NJ, Moss SM, Halloran SP, et al. Screening and primary prevention of colorectal cancer: a review of sex-specific and site-specific differences[J]. J Med Screen, 2013, 20 (3): 125-148.

84 Zell JA, Pelot D, Chen WP, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events in a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of difluoromethylornithine plus sulindac for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas[J]. Cancer Prev Res (Phila), 2009, 2 (3): 209-212.

85 Gao QY, Chen HM, Chen YX, et al. Folic acid prevents the initial occurrence of sporadic colorectal adenoma in Chinese older than 50 years of age: a randomized clinical trial[J]. Cancer Prev Res (Phila), 2013, 6 (7): 744-752.

86 Feldman D, Krishnan AV, Swami S, et al. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2014, 14 (5): 342-357.

87 Wei MY, Garland CF, Gorham ED, et al. Vitamin D and prevention of colorectal adenoma: a meta-analysis[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2008, 17 (11): 2958-2969.

88 Oh K, Willett WC, Wu K, et al. Calcium and vitamin D intakes in relation to risk of distal colorectal adenoma in women[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2007, 165 (10): 1178-1186.

89 Yamaji T, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, et al. Association between plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal adenoma according to dietary calcium intake and vitamin D receptor polymorphism[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2012, 175 (3): 236-244.

90 Hong SN, Kim JH, Choe WH, et al. Circulating vitamin D and colorectal adenoma in asymptomatic average-risk individuals who underwent first screening colonoscopy: a case-control study[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2012, 57 (3): 753-763.

91 Fedirko V, Bostick RM, Goodman M, et al. Blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 concentrations and incident sporadic colorectal adenoma risk: a pooled case-control study[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2010, 172 (5): 489-500.

92 Levine AJ, Harper JM, Ervin CM, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, dietary calcium intake, and distal colorectal adenoma risk[J]. Nutr Cancer, 2001, 39 (1): 35-41.

93 Ahmad II, Trikudanathan G, Feinn R, et al. Low serum vitamin D: A surrogate marker for advanced colon adenoma? [J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2016, 50 (8): 644-648.

94 Senesse P, Touvier M, Kesse E, et al. Tobacco use and associations of beta-carotene and vitamin intakes with colorectal adenoma risk[J]. J Nutr, 2005, 135 (10): 2468-2472.

95 Goodman M, Bostick RM, Dash C, et al. A summary measure of pro- and anti-oxidant exposures and risk of incident, sporadic, colorectal adenomas[J]. Cancer Causes Control, 2008, 19 (10): 1051-1064.

96 Enger SM, Longnecker MP, Chen MJ, et al. Dietary intake of specific carotenoids and vitamins A, C, and E, and prevalence of colorectal adenomas[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 1996, 5 (3): 147-153.

97 Neugut AI, Horvath K, Whelan RL, et al. The effect of calcium and vitamin supplements on the incidence and recurrence of colorectal adenomatous polyps[J]. Cancer, 1996, 78 (4): 723-728.

98 Almendingen K, Hofstad B, Trygg K, et al. Current diet and colorectal adenomas: a case-control study including different sets of traditionally chosen control groups[J]. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2001, 10 (5): 395-406.

99 Diergaarde B, Tiemersma EW, Braam H, et al. Dietary factors and truncating APC mutations in sporadic colorectal adenomas[J]. Int J Cancer, 2005, 113 (1): 126-132.

100 Nagata C, Shimizu H, Kametani M, et al. Diet and colorectal adenoma in Japanese males and females[J]. Dis Colon Rectum, 2001, 44 (1): 105-111.

101 Xu X, Yu E, Liu L, et al. Dietary intake of vitamins A, C, and E and the risk of colorectal adenoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2013, 22 (6): 529-539.

102 Oka S, Tanaka S, Saito Y, et al; Colorectal Endoscopic Resection Standardization Implementation Working Group of the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum, Tokyo, Japan. Local recurrence after endoscopic resection for large colorectal neoplasia: a multicenter prospective study in Japan[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2015, 110 (5): 697-707.

103 Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2008, 58 (3): 130-160.

104 Elwood PC, Gallagher AM, Duthie GG, et al. Aspirin, salicylates, and cancer[J]. Lancet, 2009, 373 (9671): 1301-1309.

105 Logan RF, Grainge MJ, Shepherd VC, et al; ukCAP Trial Group. Aspirin and folic acid for the prevention of recurrent colorectal adenomas[J]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 134 (1): 29-38.

106 Ishikawa H, Mutoh M, Suzuki S, et al. The preventive effects of low-dose enteric-coated aspirin tablets on the development of colorectal tumours in Asian patients: a randomised trial[J]. Gut, 2014, 63 (11): 1755-1759.

107 Ferrández A, Piazuelo E, Castells A. Aspirin and the prevention of colorectal cancer[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2012, 26 (2): 185-195.

108 Wang D, DuBois RN. The role of anti-inflammatory drugs in colorectal cancer[J]. Annu Rev Med, 2013, 64: 131-144.

109 Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, et al; APC Study Investigators. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas[J]. N Engl J Med, 2006, 355 (9): 873-884.

110 Arber N, Eagle CJ, Spicak J, et al; PreSAP Trial Investigators. Celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps[J]. N Engl J Med, 2006, 355 (9): 885-895.

111 Baron JA, Sandler RS, Bresalier RS, et al; APPROVe Trial Investigators. A randomized trial of rofecoxib for the chemoprevention of colorectal adenomas[J]. Gastroenterology, 2006, 131 (6): 1674-1682.

112 Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Aspirin dose and duration of use and risk of colorectal cancer in men[J]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 134 (1): 21-28.

113 Dubé C, Rostom A, Lewin G, et al; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The use of aspirin for primary prevention of colorectal cancer: a systematic review prepared for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force[J]. Ann Inter Med, 2007, 146 (5): 365-375.

114 Rostom A, Dubé C, Lewin G, et al; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygease-2 inhibitors for primary prevention of colorectal cancer: a systematic review prepared for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2007, 6 (5): 376-389.

115 Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, et al. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention[J]. N Engl J Med, 2005, 352 (11): 1071-1080.

116 Baron JA, Beach M, Mandel JS, et al. Calcium supplements for the prevention of colorectal adenomas. Calcium Polyp Prevention Study Group[J]. N Engl J Med, 1999, 340 (2): 101-107.

117 Grau MV, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al. Prolonged effect of calcium supplementation on risk of colorectal adenomas in a randomized trial[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2007, 99 (2): 129-136.

118 Cho E, Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, et al. Dairy foods, calcium, and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 10 cohort studies[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2004, 96 (13): 1015-1022.

119 Ma Y, Zhang P, Wang F, et al. Association between vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2011, 29 (28): 3775-3782.

120 Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM, et al. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2007, 85 (6): 1586-1591.

121 Grau MV, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al. Vitamin D, calcium supplementation, and colorectal adenomas: results of a randomized trial[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2003, 95 (23): 1765-1771.

122 Baron JA, Barry EL, Mott LA, et al. A Trial of calcium and vitamin D for the prevention of colorectal adenomas[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373 (16): 1519-1530.

123 Zhang X, Giovannucci E. Calcium and vitamin D for the prevention of colorectal adenomas[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 374 (8): 791.

124 Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al; Polyp Prevention Study Group. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA, 2007, 297 (21): 2351-2359.

125 Wu K, Platz EA, Willett WC, et al. A randomized trial on folic acid supplementation and risk of recurrent colorectal adenoma[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2009, 90 (6): 1623-1631.

126 Higurashi T, Hosono K, Takahashi H, et al. Metformin for chemoprevention of metachronous colorectal adenoma or polyps in post-polypectomy patients without diabetes: a multicentre double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2016, 17 (4): 475-483.

127 Greiner AK, Papineni RV, Umar S. Chemoprevention in gastrointestinal physiology and disease. Natural products and microbiome[J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2014, 307 (1): G1-G15.

128 Sears CL, Garrett WS. Microbes, microbiota, and colon cancer[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2014, 15 (3): 317-328.

129 Konstantinov SR, Kuipers EJ, Peppelenbosch MP. Functional genomic analyses of the gut microbiota for CRC screening[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 10 (12): 741-745.

130 Jess T, Rungoe C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012, 10 (6): 639-645.

131 Nieminen U, Jussila A, Nordling S, et al. Inflammation and disease duration have a cumulative effect on the risk of dysplasia and carcinoma in IBD: a case-control observational study based on registry data[J]. Int J Cancer, 2014, 134 (1): 189-196.

132 Jess T, Simonsen J, Jørgensen KT, et al. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years[J]. Gastroenterology, 2012, 143 (2): 375-381. e1.

133 Rubin DT, Huo D, Kinnucan JA, et al. Inflammation is an independent risk factor for colonic neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis: a case-control study[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 11 (12): 1601-1608. e1-e4.

134 Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, et al; SCENIC Guideline Development Panel. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Gastroenterology, 2015, 148 (3): 639-651. e28.

135 Mooiweer E, van der Meulen AE, van Bodegraven AA, et al. Neoplasia yield and colonoscopic workload of surveillance regimes for colorectal cancer in colitis patients: a retrospective study comparing the performance of the updated AGA and BSG guidelines[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2013, 19 (12): 2603-2610.

136 East JE. Colonoscopic cancer surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease: What’s new beyond random biopsy? [J]. Clin Endosc, 2012, 45 (3): 274-277.

137 Choi CH, Rutter MD, Askari A, et al. Forty-year analysis of colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: An updated overview[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2015, 110 (7): 1022-1034.

138 Velayos FS, Terdiman JP, Walsh JM. Effect of 5-aminosalicylate use on colorectal cancer and dysplasia risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2005, 100 (6): 1345-1353.

139 Velayos FS, Loftus EV Jr, Jess T, et al. Predictive and protective factors associated with colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: A case-control study[J]. Gastroenterology, 2006, 130 (7): 1941-1949.

140 Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, et al. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study[J]. Gastroenterology, 2007, 133 (4): 1099-1105; quiz 1340-1341.

141 Nguyen GC, Gulamhusein A, Bernstein CN. 5-aminosalicylic acid is not protective against colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis of non-referral populations[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012, 107 (9): 1298-1304.

142 Andrews JM, Travis SP, Gibson PR, et al. Systematic review: does concurrent therapy with 5-ASA and immunomodulators in inflammatory bowel disease improve outcomes? [J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009, 29 (5): 459-469.

143 Zhao LN, Li JY, Yu T, et al. 5-aminosalicylates reduce the risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis: an updated meta-analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9 (4): e94208.

144 van Schaik FD, van Oijen MG, Smeets HM, et al. Thiopurines prevent advanced colorectal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Gut, 2012, 61 (2): 235-240.

145 Beaugerie L, Svrcek M, Seksik P, et al; CESAME Study Group. Risk of colorectal high-grade dysplasia and cancer in a prospective observational cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 145 (1): 166-175. e8.

146 Gong J, Zhu L, Guo Z, et al. Use of thiopurines and risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a meta-analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8 (11): e81487.

147 Wang R, Leong RW. Primary sclerosing cholangitis as an independent risk factor for colorectal cancer in the context of inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20 (27): 8783-8789.

148 李景南, 郑威扬, 钱家鸣, 等. 溃疡性结肠炎相关结直肠癌临床特点及癌变相关蛋白的表达[J]. 中华消化杂志, 2010, 30 (11): 808-810.

149 Lindström L, Boberg KM, Wikman O, et al. High dose ursodeoxycholic acid in primary sclerosing cholangitis does not prevent colorectal neoplasia[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2012, 35 (4): 451-457.

150 Singh S, Khanna S, Pardi DS, et al. Effect of ursodeoxycholic acid use on the risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2013, 19 (8): 1631-1638.

151 Hansen JD, Kumar S, Lo WK, et al. Ursodiol and colorectal cancer or dysplasia risk in primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2013, 58 (11): 3079-3087.

152 Sood A, Midha V, Makharia GK, et al. The probiotic preparation, VSL#3 induces remission in patients with mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009, 7 (11): 1202-1209. e1.

153 Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Papa A, et al. Treatment of relapsing mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with the probiotic VSL#3 as adjunctive to a standard pharmaceutical treatment: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2010, 105 (10): 2218-2227.

155 Meyer R, Laubert T, Sommer M, et al. Colorectal neoplasia in IBD -- a single-center analysis of patients undergoing proctocolectomy[J]. Int J Colorectal Dis, 2015, 30 (6): 821-829.

156 Althumairi AA, Lazarev MG, Gearhart SL. Inflammatory bowel disease associated neoplasia: A surgeon’s perspective[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22 (3): 961-973.

157 Dunlop MG, Farrington SM, Carothers AD, et al. Cancer risk associated with germline DNA mismatch repair gene mutations[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 1997, 6 (1): 105-110.

158 Aaltonen LA, Salovaara R, Kristo P, et al. Incidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and the feasibility of molecular screening for the disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 1998, 338 (21): 1481-1487.

159 Barnetson RA, Tenesa A, Farrington SM, et al. Identification and survival of carriers of mutations in DNA mismatch-repair genes in colon cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2006, 354 (26): 2751-2763.

160 Hampel H, Frankel WL, Martin E, et al. Screening for the Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) [J]. N Engl J Med, 2005, 352 (18): 1851-1860.

161 Salovaara R, Loukola A, Kristo P, et al. Population-based molecular detection of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2000, 18 (11): 2193-2200.

162 Bonadona V, Bonaïti B, Olschwang S, et al; French Cancer Genetics Network. Cancer risks associated with germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 genes in Lynch syndrome[J]. JAMA, 2011, 305 (22): 2304-2310.

163 Quehenberger F, Vasen HF, van Houwelingen HC. Risk of colorectal and endometrial cancer for carriers of mutations of the hMLH1 and hMSH2 gene: correction for ascertainment[J]. J Med Genet, 2005, 42 (6): 491-496.

164 Jenkins MA, Baglietto L, Dowty JG, et al. Cancer risks for mismatch repair gene mutation carriers: a population-based early onset case-family study[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2006, 4 (4): 489-498.

165 Alarcon F, Lasset C, Carayol J, et al. Estimating cancer risk in HNPCC by the GRL method[J]. Eur J Hum Genet, 2007, 15 (8): 831-836.

166 Baglietto L, Lindor NM, Dowty JG, et al. Risks of Lynch syndrome cancers for MSH6 mutation carriers[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2010, 102 (3): 193-201.

167 Choi YH, Cotterchio M, McKeown-Eyssen G, et al. Penetrance of colorectal cancer among MLH1/MSH2 carriers participating in the colorectal cancer familial registry in Ontario[J]. Hered Cancer Clin Pract, 2009, 7 (1): 14.

168 Hendriks YM, Wagner A, Morreau H, et al. Cancer risk in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer due to MSH6 mutations: impact on counseling and surveillance[J]. Gastroenterology, 2004, 127 (1): 17-25.

169 Senter L, Clendenning M, Sotamaa K, et al. The clinical phenotype of Lynch syndrome due to germ-line PMS2 mutations[J]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 135 (2): 419-428.

170 Lindor NM, Petersen GM, Hadley DW, et al. Recommendations for the care of individuals with an inherited predisposition to Lynch syndrome: a systematic review[J]. JAMA, 2006, 296 (12): 1507-1517.

171 Vasen HF, Blanco I, Aktan-Collan K, et al; Mallorca group. Revised guidelines for the clinical management of Lynch syndrome (HNPCC): recommendations by a group of European experts[J]. Gut, 2013, 62 (6): 812-823.

172 Dove-Edwin I, Boks D, Goff S, et al. The outcome of endometrial carcinoma surveillance by ultrasound scan in women at risk of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma and familial colorectal carcinoma[J]. Cancer, 2002, 94 (6): 1708-1712.

173 Rijcken FE, Mourits MJ, Kleibeuker JH, et al. Gynecologic screening in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer[J]. Gynecol Oncol, 2003, 91 (1): 74-80.

174 Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Bützow R, Leminen A, et al. Surveillance for endometrial cancer in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome[J]. Int J Cancer, 2007, 120 (4): 821-824.

175 Lécuru F, Le Frère Belda MA, Bats AS, et al. Performance of office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy for detecting endometrial disease in women at risk of human non-polyposis colon cancer: a prospective study[J]. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2008, 18 (6): 1326-1331.

176 Gerritzen LH, Hoogerbrugge N, Oei AL, et al. Improvement of endometrial biopsy over transvaginal ultrasound alone for endometrial surveillance in women with Lynch syndrome[J]. Fam Cancer, 2009, 8 (4): 391-397.

177 Stuckless S, Green J, Dawson L, et al. Impact of gynecological screening in Lynch syndrome carriers with an MSH2 mutation[J]. Clin Genet, 2013, 83 (4): 359-364.

178 Evans DG, Gaarenstroom KN, Stirling D, et al. Screening for familial ovarian cancer: poor survival of BRCA1/2 related cancers[J]. J Med Genet, 2009, 46 (9): 593-597.

179 张宏, 王简, 吕操, 等. 遗传性非息肉病性结直肠癌家系肿瘤谱特点分析[J]. 中国肿瘤临床, 2005, 32 (7): 386-388.

180 Aarnio M, Salovaara R, Aaltonen LA, et al. Features of gastric cancer in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer syndrome[J]. Int J Cancer, 1997, 74 (5): 551-555.

181 Capelle LG, Van Grieken NC, Lingsma HF, et al. Risk and epidemiological time trends of gastric cancer in Lynch syndrome carriers in the Netherlands[J]. Gastroenterology, 2010, 138 (2): 487-492.

182 Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Sipponen P, Aarnio M, et al. No support for endoscopic surveillance for gastric cancer in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2002, 37 (5): 574-577.

183 National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colorectal Cancer Screening[DB/OL]. Version 2. 2012. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/olorectalscreening.pdf. Accessed November 1,2013.

184 Win AK, Parry S, Parry B, et al. Risk of metachronous colon cancer following surgery for rectal cancer in mismatch repair gene mutation carriers[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2013, 20 (6): 1829-1836.

185 崔伟佳, 盛剑秋, 陆晓娟, 等. 中国人家族性腺瘤性息肉病的基因型与临床表型的关系分析[J]. 基础医学与临床, 2009, 29 (6): 589-592.

186 Moisio AL, Järvinen H, Peltomäki P. Genetic and clinical characterisation of familial adenomatous polyposis: a population based study[J]. Gut, 2002, 50 (6): 845-850.

187 Grover S, Kastrinos F, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prevalence and phenotypes of APC and MUTYH mutations in patients with multiple colorectal adenomas[J]. JAMA, 2012, 308 (5): 485-492.

188 Sieber OM, Lipton L, Crabtree M, et al. Multiple colorectal adenomas, classic adenomatous polyposis, and germ-line mutations in MYH[J]. N Engl J Med, 2003, 348 (9): 791-799.

189 Sheng JQ, Cui WJ, Fu L, et al. APC gene mutations in Chinese familial adenomatous polyposis patients[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2010, 16 (12): 1522-1526.

190 Guarinos C, Juárez M, Egoavil C, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of MUTYH-associated polyposis in patients with multiple adenomatous and serrated polyps[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2014, 20 (5): 1158-1168.

191 Ponz de Leon M, Bianchini MA, Reggiani-Bonetti L, et al. An unusual case of familial adenomatous polyposis with very early symptom occurrence[J]. Fam Cancer, 2014, 13 (3): 375-380.

192 Vasen HF, Bülow S, Myrhøj T, et al. Decision analysis in the management of duodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposis[J]. Gut, 1997, 40 (6): 716-719.

193 Benson AB 3rd, Venook AP, Bekaii-Saab T, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Colon cancer, version 3.2014[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2014, 12 (7): 1028-1059.

194 Groves C, Lamlum H, Crabtree M, et al. Mutation cluster region, association between germline and somatic mutations and genotype-phenotype correlation in upper gastrointestinal familial adenomatous polyposis[J]. Am J Pathol, 2002, 160 (6): 2055-2061.

195 Bülow S, Björk J, Christensen IJ, et al; DAF Study Group. Duodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposis[J]. Gut, 2004, 53 (3): 381-386.

196 Latchford AR, Neale KF, Spigelman AD, et al. Features of duodenal cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009, 7 (6): 659-663.

197 Drini M, Speer A, Dow C, et al. Management of duodenal adenomatosis in FAP: single centre experience[J]. Fam Cancer, 2012, 11 (2): 167-173.

198 Iaquinto G, Fornasarig M, Quaia M, et al. Capsule endoscopy is useful and safe for small-bowel surveillance in familial adenomatous polyposis[J]. Gastrointest Endosc, 2008, 67 (1): 61-67.

199 Tulchinsky H, Keidar A, Strul H, et al. Extracolonic manifestations of familial adenomatous polyposis after proctocolectomy[J]. Arch Surg, 2005, 140 (2): 159-163.

200 Galiatsatos P, Foulkes WD. Familial adenomatous polyposis[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2006, 101 (2): 385-398.

201 Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2015, 110 (2): 223-262.

(2016-07-14收稿)

10.3969/j.issn.1008-7125.2016.11.006

*本文通信作者,房静远,上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院消化科(200001),Email: fangjingyuan_new@163.com