靶向CD123抗原嵌合受体T细胞治疗急性髓系白血病的研究

2016-11-18孙耀张斌陈虎

孙耀 张斌 陈虎

·综述·

靶向CD123抗原嵌合受体T细胞治疗急性髓系白血病的研究

孙耀 张斌 陈虎

急性髓系白血病(AML)是一种预后较差的血液系统恶性肿瘤,迫切需要新的治疗手段。随着嵌合抗原受体(CAR)T细胞(CAR-T)技术的发展并在B细胞肿瘤中取得显著疗效,人们把目光投入更多的实体瘤与血液肿瘤靶点中。CD123分子是CAR-T治疗AML的潜在靶点,抗CD123 CAR-T具有靶向清除白血病干细胞(LSCs)及原始细胞的能力。本研究总结了目前在靶向CD123 CAR-T治疗急性髓系白血病目前的研究进展。

白血病,急性; 抗原; 受体; 干细胞; 白细胞介素3受体α亚单位; T细胞

急性髓系白血病(acute myeloid leukemia,AML)是血液系统的一种恶性肿瘤,以克隆性增殖异常分化的恶性细胞浸润骨髓、血液及其他组织为特点[1-2]。大量研究表明AML起源于一群数量相对较小的干祖细胞,即白血病干细胞(leukemia stem cells,LSCs)。CD123是一种包含360氨基酸的糖蛋白,广泛地表达在白血病原始细胞和白血病干细胞表面,尤其是AML。目前已研发出几种靶向CD123的单克隆抗体类药物并正在进行临床前及临床试验,靶向CD123的抗原受体(chimeric antigen receptor-modifyin,CAR)T细胞(CAR-T)治疗也已完成临床前研究并显示出显著的抗瘤效应,目前处于Ⅰ期临床试验阶段。

一、AML治疗现状

自40多年前阿糖胞苷3 d,环磷酰胺7 d化疗方案取得成功后,AML不再是不治之症,但此后在AML治疗上没有突破性进展[3]。至今AML仍是一种威胁生命的恶性肿瘤,总生存率为70﹪,在60岁以下成人中治愈率为35~40﹪,而在60以上成人中治愈率仅为5﹪~15﹪[4-5]。对于诱导缓解失败的患者,5年生存率仅7﹪~12﹪[6]。对于复发难治AML最好的治疗办法仍然是异基因造血干细胞移植(hematopoietic stem cell transplantation,allo-HSCT),而其造成的移植物抗宿主病(graft-versus-host disease,GVHD)、感染等严重并发症也影响了患者的生存。

二、CD123是AML的治疗靶点

(一)CD123是白血病干细胞主要标志

随着对白血病发病机制的深入研究,发现在髓系白血病中存在一群保持自我更新分化能力的白血病细胞,即LSCs,其在白血病细胞中数量较少,主要呈静止状态[7]。LSCs在表面分子上以CD34+,CD38-,CD71-,HLA-DR-,CD90-,CD123-,CLL-1+,TIM3+等为特点[7-11]。

目前许多化疗药物治疗肿瘤的机制是杀灭分裂期细胞,AML化疗也是如此并极易复发,LSCs的存在也许解释了AML化疗后易复发的原因。并且,相关报道已证实LSCs在一定程度上对柔红霉素加阿糖胞苷方案不敏感[7]。所以有效针对LSCs的治疗,可能会成为治疗复发难治AML的新策略。

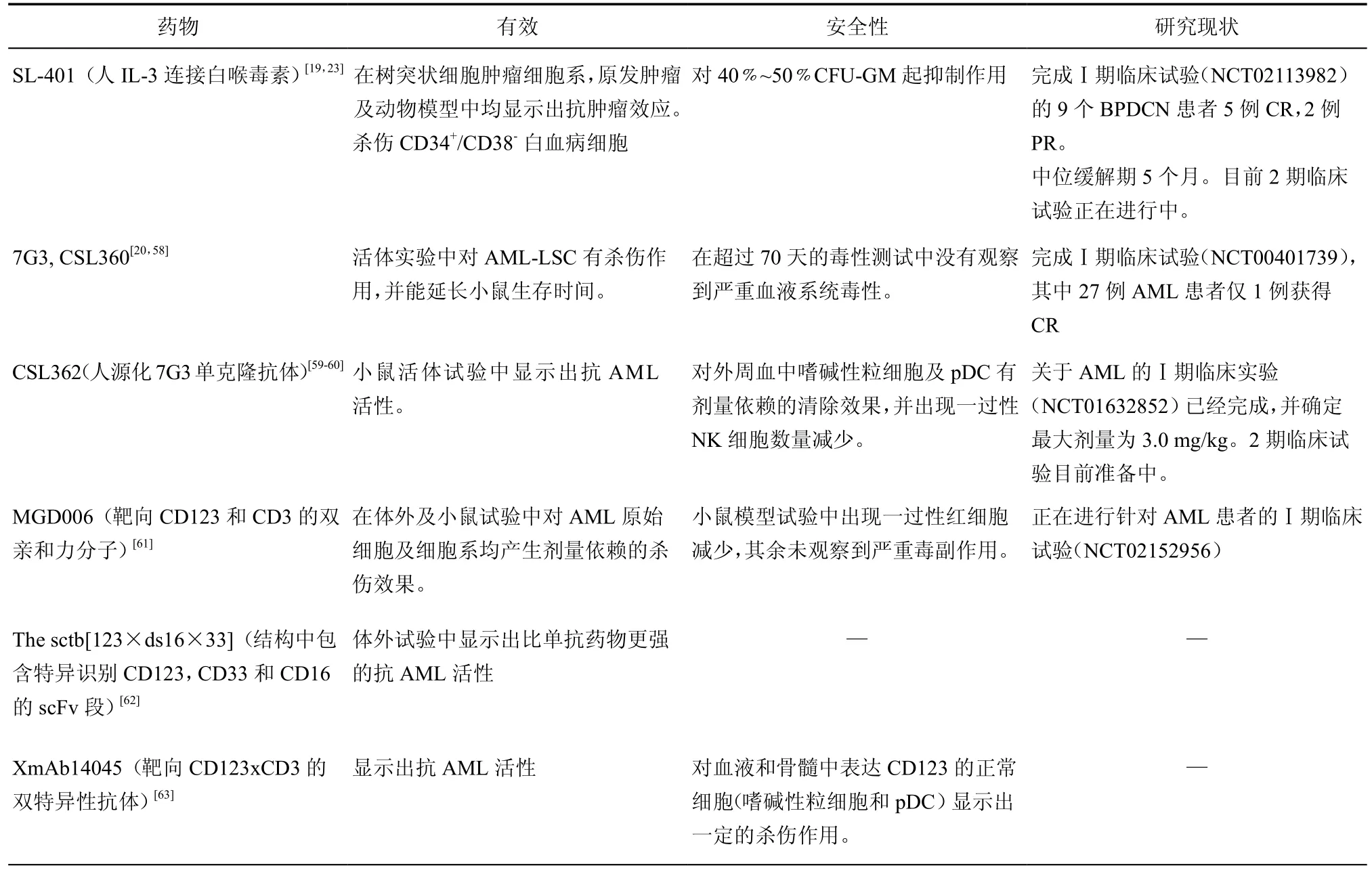

表1 基于CD123单抗药物现状

(二)CD123表达情况

CD123是一种糖蛋白,同时也是白细胞介素3受体跨膜α亚单位(IL-3Ra),与CD131一起组成高亲和力的IL-3受体,一旦与IL-3结合,则促进细胞增殖及存活。

1. CD123正常表达

CD123主要在造血系统中表达,CD123在正常CD34+CD38-细胞中低表达或者不表达[12],Taussig等[13]发现,在脐带血中大多数CD34+/CD38-细胞表达CD123,而骨髓CD34+/CD38-细胞中CD123+细胞比例较低。此外,正常情况下在髓系祖细胞、B淋巴祖细胞中CD123有较高表达,而红系祖细胞和多向分化潜能祖细胞中低表达或不表达[14-15];浆细胞样树突状细胞与嗜碱性粒细胞中高表达,而在嗜酸性粒细胞、单核细胞和髓系树突状细胞中低表达[16]。

2.CD123异常表达

CD123在AML-LSC及AML原始细胞均高表达[12,17-18]。在NSG小鼠模型中,CD34+/CD38-/CD123+细胞群较 CD34+/ CD38-/CD123+细胞群有更强的重建AML能力;AML原始细胞中CD123的高表达与信号转导与转录激活因子5(signal transducer and activator of transcription 5, STAT5)信号通路的活化相关。在临床上,初诊时原始细胞数量越高的患者,CD123的表达水平越高;CD123高表达的患者与CD123正常患者相比预后更差[19]。这些研究都说明CD123可能与白血病的发生密切相关。

除了在AML中表达,CD123在慢性粒细胞白血病,骨髓增生异常综合症及肥大细胞增多症,B-细胞急性淋巴细胞白血病(B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia,B-ALL)[20]中也有所表达。最近,Du等[21]首次报道T-细胞急性淋巴细胞白血病(T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia,T-ALL)也表达CD123。

Jingmei等[22]发现CD123在造血干细胞移植后急性GVHD患者中升高,可作为一个重要辅助指标用于鉴别急性GVHD及巨细胞病毒感染,特别是对于胃肠道病变。

CD123是LSCs的主要标志,同时在AML原始细胞中表达比例明显高于正常细胞,尤其是CD34+CD38-细胞,使CD123成为AML靶向治疗可行靶点,并且有望为AML治疗带来新的突破。

(三)靶向CD123抗体药物

目前关于CD123单抗药物的研究总结见表1。靶向CD123的抗体药物虽然均处于早期临床试验阶段,也并未展现出突出疗效,但仍是目前研究的热点。Ⅰ期临床研究中患者表现展现出良好的耐受性,没有出现严重的血液系统不良反应。针对浆细胞样树突状细胞肿瘤的治疗(SL-401)取得了较高缓解率,其中一名患者缓解时间长达20个月以上,但初始有反应的3名患者复发后再次治疗均无效[23]。而在另一项针对AML临床研究(CSL360)中完全反应率较低,仅1/27达CR[20],说明靶向CD123的抗体药物尚需要通过优化抗体亲和力、多靶点抗体结合等方法,增强抗肿瘤活性。

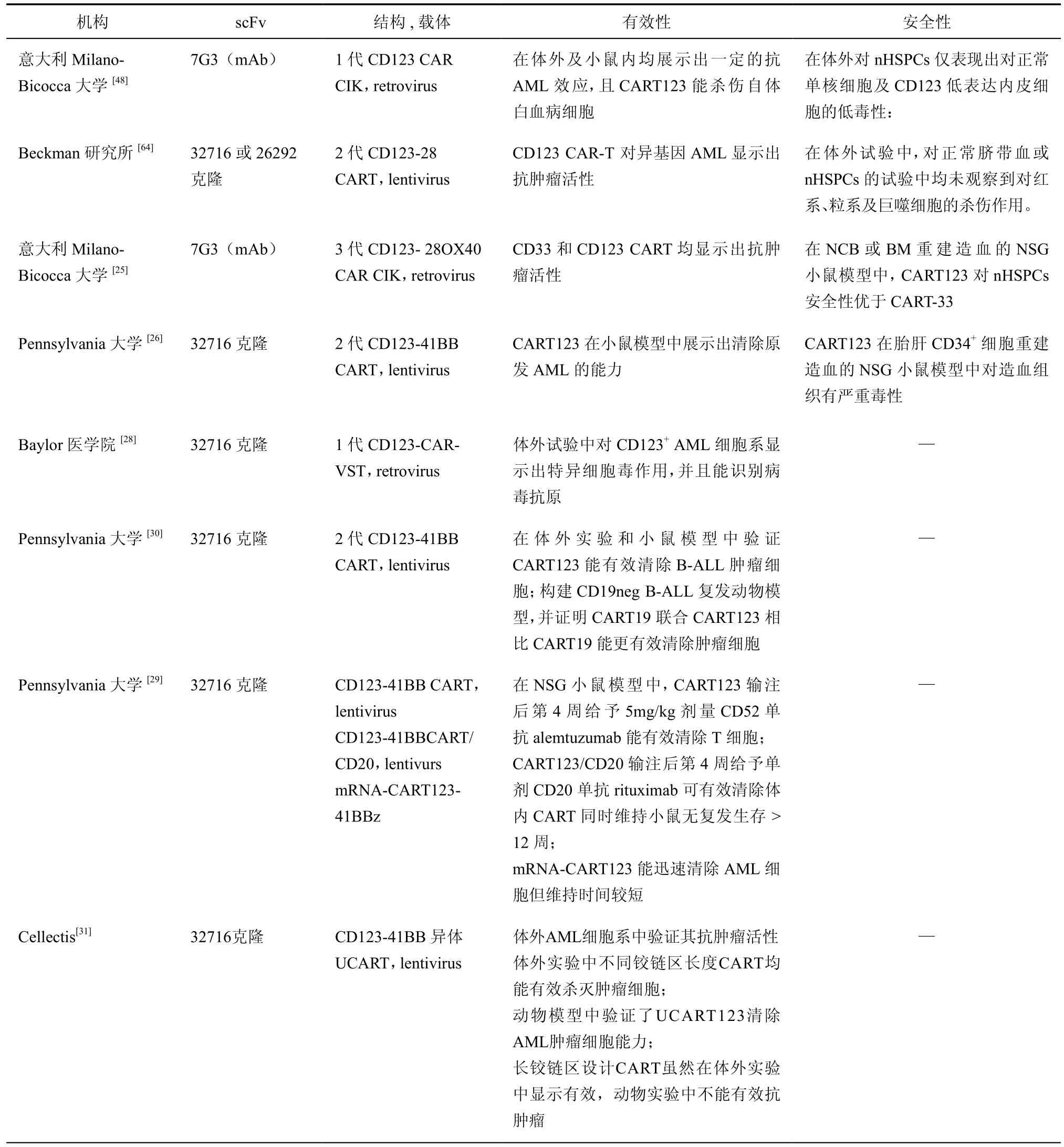

表2 CART123临床前研究汇总

(四)CD123 CART临床前研究

目前关于CD123的临床前研究汇总于表2,部分研究中发生造血系统毒性,安全性有待商榷。Pizzitola等[25]将CD28、OX40共刺激分子作为胞内段,较二代CAR增加了IFN-γ,TNF-α,TNF-β和IL-2等细胞因子分泌水平,提高了抗肿瘤效应,且没有增加其对造血系统的毒性。Moretti等[16]研究发现,来自脐血的CD34+正常造血祖细胞与CART123共培养后仍保留正常增殖分化能力。Gill等[26]首次提出CART123安全性问题,他们在体外及胎肝CD34+细胞重建的NSG小鼠模型中均观察到CART123引起严重的造血系统,主要是CD34+CD38-细胞,及B淋巴细胞、血小板及髓系细胞数量的减少,并建议将CART123作为一种HSCT前的清髓方案更加安全。当然,不同来源造血组织CD123表达水平不一,Huang等[15]指出在CD34+胎肝细胞中CD123表达水平高于脐血或骨髓来源CD34+细胞。由于个体、组织来源不同均可导致CD123表达水平的差异,故靶向表达CD123正常细胞引起的毒性反应不可避免。选择合理阈值采取干预措施,或通过scFv,CAR结构的改善提高特异性,可能成为未来提高CART123安全性的策略。考虑到AML移植后患者易感染EB病毒,巨细胞病毒等病毒且常规药物治疗疗效差或副作用大,最近Zhou等[28]设计了一种CD123-CAR-VST,既能杀伤CD123+AML细胞又对EMV等病毒感染有一定的控制作用。

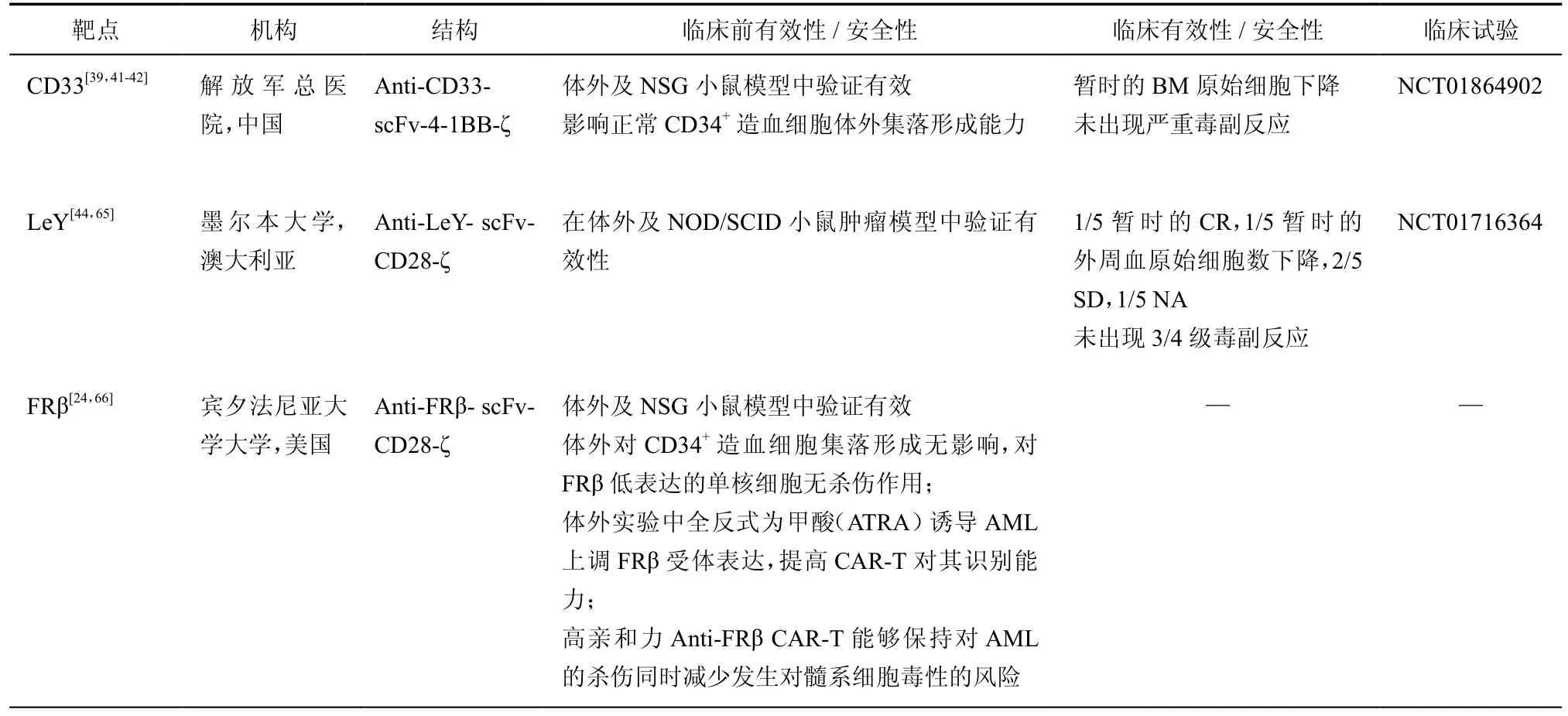

表3 其他治疗AML的CART研究进展

Tasian等[29]假设CART123清除体内AML细胞后及时清除CART细胞,能够在一定程度上保持对AML的控制同时减少靶向CD123毒性发生,并且比较了3种不同方法清除CART的效果。

Ruella等[30]发现80﹪的B-ALL原始细胞中表达CD123,并在CD19阴性复发的B-ALL肿瘤细胞中检测到。在体外实验和动物模型中,CART123不仅能有效清除B-ALL肿瘤细胞,并且CART19联合CART123相比CART19能更有效清除CD19阴性复发肿瘤细胞,可能解决目前CART19治疗后复发率的问题。

Celletis公司继UCART19后,研发了异体UCART123,通过TALEN技术敲除TCRα消除GvHD作用,从而可实现“off-the-shelf”,即通过正常供者T细胞大规模制备CART,较自体CART明显缩短制备时间[31]。

(五)CD123 CAR-T临床试验方案

截至目前,有两个CD123 CAR-T治疗AML患者的Ⅰ期临床试验在开展中。第一个是由美国希望之城医学中心注册(NCT02159495),采用CAR123-28z结构,以减少CAR-T体内存留时间,因为文献表明以CD28作为胞内段的第二代CAR结构在体内存活时间仅1个月[32];并且携带有自杀基因EGFRt,能够在EGFR单抗作用下清除CAR-T。此外,他们将CART123作为allo-HSCT前的清髓方案,以最大限度减少肿瘤负荷[6]。第二个是由Pennsylvania大学注册的CD123-BBz二代CAR(NCT02623582),由于前期研究中发现了对造血系统的损伤,在临床试验中采用电转RNA-CART多次输注策略确保安全。

在57th ASH会议上,Luo等[27]口头报告了首例CART123治疗AML患者案例。他们设计的CD123-scFv/ CD28/CD137/CD27/CD3ζ-iCasp9(4SCAR123)4代CAR在患者接受预处理(CTX 250mg/kg/day3天方案)后输注。输注后患者出现了严重细胞因子风暴综合症,通过单次给与妥珠单抗Tocilizumab(IL-6R拮抗剂)后得到控制。患者的骨髓原始细胞治疗前59﹪,CART输注后20 d降低至40﹪,并尚未观察到严重毒副作用。

(六)其他治疗AML的CAR-T细胞靶点

目前治疗AML的CAR-T研究临床试验注册情况如表3所示,除CD123以外,仅靶向CD33和Lewis Y的研究公布了临床试验阶段的数据。目前主要的AML治疗靶点有CD33,Lewis Y,FRβ。此外,TIM-3,CLL-1等由于其表达特异性,也有望成为AML治疗靶点[11,33]。

1. CD33:CD33(Siglec-3)在90﹪的AML原始细胞中持续表达,同时在多能髓系祖细胞,成熟粒、单细胞及单能干细胞等细胞中表达[34-39]。CD33是AML中第一个用于单抗药物及免疫治疗治疗的表面分子。但由于白血病细胞及正常造血细胞中表达水平相近,缺乏特异性,在临床试验中观察到明确的毒性而致使安全性未得到一直公认[40]。一些关于CART-33的临床前研究显示了其抗肿瘤效应[41],其中Marin等[42]观察到其对nHPCs的毒性,解放军总医院Wang等[39]开展了全球首例CART-33临床试验(NCT01864902)并且治疗了1例AML患者。尽管观察到了短暂的疗效,其安全性及有效性仍待进一步探讨。不幸的是介于CD33单抗药物GO的严重副作用,关于CD33的临床试验目前被暂停。而Pizzitola等[25]研究发现相比于CART33,CART123有同等的抗AML效应且安全性更好。

2. Lewis Y:Lewis Y是一种功能尚未知的岩藻糖抗原,它在大量蛋白中均可检测到,包括肿瘤相关抗原[43]。并且在包括AML在内的广泛恶性肿瘤中表达拷贝数很高,而在正常组织中表达较低,其表达越多预后越差[44]。

3.FRβ:叶酸受体(FR)家族由α,β,γ和δ 4个已知成员组成的一组叶酸结合蛋白受体,并且这些受体的分布具有组织特异性:FRα主要分布于上皮组织,而FRβ主要分布于髓系造血细胞中[45]。这些受体在恶性肿瘤中普遍出现上调,其中FRβ在70﹪左右的AML患者肿瘤中检测到,使其成为一个AML治疗具有潜力的靶点[46-47]。

五、结论

将目前基于7G3序列的CD123单抗药物在Ⅰ期临床试验中的结果并不理想,而相应的CART123在临床前的试验中显示出明显的抗肿瘤效应[25,48],说明了CAR-T在髓系肿瘤上应用的潜能。研究已表明,从CAR结构上,4-1BB胞内段能避免T细胞无反应性,并促进T细胞增殖及产生记忆细胞,对T细胞在体内的持续明显优于CD28,且4-1BBL优于4-1BB胞内段设计,而CD28胞内段设计则优于CD80胞外段[49],意味着未来CAR-T设计将不断优化,获得更好疗效。而同时介于CART123可能带来的造血毒性,增加CART123可控性成为开展临床试验的必要前提。除了瞬时转染、序贯以allo-HSCT以外,还可采用iCAR-T[50]、synNotch CAR[51-52]等设计可能会减少其脱靶效应的发生率;另一方面,采用HSV-TK kinases自杀基因策略,可杀灭增殖中的CAR-T细胞,控制GVHD作用,而保有少量CAR-T在体内,起到免疫监视作用[53],最新的相关“分子开关”机制,通过抗体药物或小分子药物调控CAR-T在体内发挥作用[54-57],也给CAR-T治疗可控性带来了新的思路。总而言之,有效的抗肿瘤效果结合适当的可控性,将是未来CART123治疗AML 的发展方向。

1 Dohner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(12):1136-1152.

2 陆晓茜, 马志贵, 高举, 等. 维A酸X受体信号通路与白血病[J]. 器官移植, 2014, 5(6):383-388.

3 Grosso DA, Hess RC, Weiss MA. Immunotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia[J]. Cancer, 2015, 121(16):2689-2704.

4 Creutzig U, Van Den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Gibson B, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in children and adolescents: recommendations from an international expert panel[J]. Blood, 2012, 120(16):3187-3205.

5 Döhner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet[J]. Blood, 2010, 115(3):453-474.

6 Mardiros A, Forman SJ, Budde LE. T cells expressing CD123 chimeric antigen receptors for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia[J]. Curr Opin Hematol, 2015, 22(6):484-488.

7 Konopleva MY, Jordan CT. Leukemia stem cells and microenvironment: biology and therapeutic targeting[J]. J Clin Oncol,2011, 29(5):591-599.

8 Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice[J]. Nature,1994, 367(6464):645-648.

9 Forman SJ, Rowe JM. The myth of the second remission of acute leukemia in the adult[J]. Blood, 2013, 121(7):1077-1082.

10 Jordan CT. Unique molecular and cellular features of acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells[J]. Leukemia, 2002, 16(4):559-562.

11 Kikushige Y, Shima T, Takayanagi S, et al. TIM-3 is a promising target to selectively kill acute myeloid leukemia stem cells[J]. Cell Stem Cell,2010, 7(6):708-717.

12 Jordan CT, Upchurch D, Szilvassy SJ, et al. The interleukin-3 receptor alpha chain is a unique marker for human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells[J]. Leukemia, 2000, 14(10):1777-1784.

13 Pelosi E, Castelli G, Testa U. Targeting LSCs through membrane antigens selectively or preferentially expressed on these cells[J]. Blood Cells Molecules and Diseases, 2015, 55(4):336-346.

14 Wognum AW, De Jong MO, Wagemaker G. Differential expression of receptors for hemopoietic growth factors on subsets of CD34+hemopoietic cells[J]. Leuk Lymphoma, 1996, 24(1/2):11-25.

15 Huang S, Chen Z, Yu JF, et al. Correlation between IL-3 receptor expression and growth potential of human CD34+hematopoietic cells from different tissues[J]. Stem Cells, 1999, 17(5):265-272.

16 Moretti S, Lanza F, Dabusti M, et al. CD123 (interleukin 3 receptor alpha chain)[J]. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents, 2001, 15(1):98-100.

17 Du W, Li XE, Sipple J, et al. Overexpression of IL-3Rα on CD34+CD38-stem cells defines leukemia-initiating cells in Fanconi anemia AML[J]. Blood, 2011, 117(16):4243-4252.

18 Muñoz L, Nomdedéu JF, López O, et al. Interleukin-3 receptor alpha chain (CD123) is widely expressed in hematologic malignancies[J]. Haematologica, 2001, 86(12):1261-1269.

19 Testa U, Riccioni R, Militi S, et al. Elevated expression of IL-3Ralpha in acute myelogenous leukemia is associated with enhanced blast proliferation, increased cellularity, and poor prognosis[J]. Blood, 2002,100(8):2980-2988.

20 Jin L, Lee EM, Ramshaw HS, et al. Monoclonal antibody-mediated targeting of CD123, IL-3 receptor alpha chain, eliminates human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2009, 5(1):31-42.

21 Du W, Li J, Liu W, et al. Interleukin-3 receptor α chain (CD123) is preferentially expressed in immature T-ALL and May not associate with outcomes of chemotherapy[J]. Tumour Biol, 2016, 37(3):3817-3821.

22 Lin J, Chen S, Zhao Z, et al. CD123 is a useful immunohistochemical marker to facilitate diagnosis of acute graft-versus-host disease in colon[J]. Hum Pathol, 2013, 44(10):2075-2080.

23 Frankel AE, Woo JH, Ahn C, et al. Activity of SL-401, a targeted therapy directed to interleukin-3 receptor, in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm patients[J]. Blood, 2014, 124(3):385-392.

24 Lynn RC, Poussin M, Kalota A, et al. Targeting of folate receptor β on acute myeloid leukemia blasts with chimeric antigen receptorexpressing T cells[J]. Blood, 2015, 125(22):3466-3476.

25 Pizzitola I, Anjos-Afonso F, Rouault-Pierre K, et al. Chimeric antigen receptors against CD33/CD123 antigens efficiently target primary acute myeloid leukemia cells in vivo[J]. Leukemia, 2014, 28(8):1596-1605.

26 Gill S, Tasian SK, Ruella M, et al. Preclinical targeting of human acute myeloid leukemia and myeloablation using chimeric antigen receptormodified T cells[J]. Blood, 2014, 123(15):2343-2354.

27 Luo Y, Chang LJ, Hu YX, et al. First-in-Man CD123-Specific chimeric antigen Receptor-Modified T cells for the treatment of refractory acute myeloid leukemia[C/OL]// 57th ASH Annual Meeting & Exposition,Orlando, 2015[2016-02-21]. https://ash.confex.com/ash/2015/ webprogram/Paper85290.html.

28 Zhou L, Liu X, Wang X, et al. CD123 redirected multiple virus-specific T cells for acute myeloid leukemia[J]. Leuk Res, 2016, 41:76-84.

29 Tasian SK, Kenderian SS, Shen F, et al. Efficient termination of CD123-Redirected chimeric antigen receptor T cells for acute myeloid leukemia to mitigate toxicity[J]. Blood, 2015, 126(23):565-565.

30 Ruella M, Barrett DM, Kenderian SS, et al. Treatment of leukemia antigen-loss relapses occurring after CD19-targeted immunotherapies by combination of anti-CD123 and anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2015, 3(S2):O5.

31 Galetto R, Lebuhotel C, Françon P, et al. Allogenic T-Cells targeting CD123 for adoptive immunotherapy of acute myeloid leukemia(AML)[J]. Blood, 2014, 124 (21):1116.

32 Norelli M, Casucci M, Bonini C, et al. Clinical pharmacology of CAR-T cells: Linking cellular pharmacodynamics to pharmacokinetics and antitumor effects[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2016, 1865(1):90-100. 33 Van Rhenen A, Van Dongen GA, Kelder A, et al. The novel AML stem cell associated antigen CLL-1 aids in discrimination between normal and leukemic stem cells[J]. Blood, 2007, 110(7):2659-2666.

34 Feldman EJ, Brandwein J, Stone R, et al. Phase III randomized multicenter study of a humanized anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody,lintuzumab, in combination with chemotherapy, versus chemotherapy alone in patients with refractory or first-relapsed acute myeloid leukemia[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2005, 23(18):4110-4116.

35 Pearce DJ, Taussig D, Zibara K, et al. AML engraftment in the NOD/SCID assay reflects the outcome of AML: implications for our understanding of the heterogeneity of AML[J]. Blood, 2006,107(3):1166-1173.

36 Nakahata T, Okumura N. Cell surface antigen expression in human erythroid progenitors: erythroid and megakaryocytic markers[J]. Leuk Lymphoma, 1994, 13(5/6):401-409.

37 Taussig DC, Pearce DJ, Simpson C, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells Express multiple myeloid markers: implications for the origin and targeted therapy of acute myeloid leukemia[J]. Blood, 2005,106(13):4086-4092.

38 Hernández-Caselles T, Martínez-Esparza M, Pérez-Oliva AB, et al. A study of CD33 (SIGLEC-3) antigen expression and function on activated human T and NK cells: two isoforms of CD33 are generated by alternative splicing[J]. J Leukoc Biol, 2006, 79(1):46-58.

39 Wang QS, Wang Y, Lv HY, et al. Treatment of CD33-directed chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in one patient with relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia[J]. Mol Ther, 2015, 23(1):184-191.

40 Larson RA, Sievers EL, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Final report of the efficacy and safety of gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) in patients with CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in first recurrence[J]. Cancer, 2005, 104(7):1442-1452.

41 Dutour A, Marin V, Pizzitola I, et al. In vitro and in vivo antitumor effect of Anti-CD33 chimeric Receptor-Expressing EBV-CTL against CD33 acute myeloid leukemia[J]. Adv Hematol, 2012:683065.

42 Marin V, Pizzitola I, Agostoni V, et al. Cytokine-induced killer cells for cell therapy of acute myeloid leukemia: improvement of their immune activity by expression of CD33-specific chimeric receptors[J]. Haematologica, 2010, 95(12):2144-2152.

43 Yin BW, Finstad CL, Kitamura K, et al. Serological and immunochemical analysis of Lewis y (Ley) blood group antigen expression in epithelial ovarian cancer[J]. Int J Cancer, 1996,65(4):406-412.

44 Ritchie DS, Neeson PJ, Khot A, et al. Persistence and efficacy of second Generation CAR T cell against the LeY antigen in acute myeloid leukemia[J]. Mol Ther, 2013, 21(11):2122-2129.

45 Shen F, Ross JF, Wang X, et al. Identification of a novel folate receptor,a truncated receptor, and receptor type beta in hematopoietic cells:cDNA cloning, expression, immunoreactivity, and tissue specificity[J]. Biochemistry, 1994, 33(5):1209-1215.

46 Ross JF, Wang H, Behm FG, et al. Folate receptor type beta is a neutrophilic lineage marker and is differentially expressed in myeloid leukemia[J]. Cancer, 1999, 85(2):348-357.

47 Pan XQ, Zheng X, Shi G, et al. Strategy for the treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia based on folate receptor beta-targeted liposomal doxorubicin combined with receptor induction using all-trans retinoic acid[J]. Blood, 2002, 100(2):594-602.

48 Tettamanti S, Marin V, Pizzitola I, et al. Targeting of acute myeloid leukaemia by cytokine-induced killer cells redirected with a novel CD123-specific chimeric antigen receptor[J]. Br J Haematol, 2013,161(3):389-401.

49 Zhao Z, Condomines M, Van Der Stegen SJ, et al. Structural design of engineered costimulation determines tumor rejection kinetics and persistence of CAR T cells[J]. Cancer Cell, 2015, 28(4):415-428.

50 Fedorov VD, Themeli M, Sadelain M. PD-1- and CTLA-4-based inhibitory chimeric antigen receptors (iCARs) divert off-target immunotherapy responses[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2013, 5(215):215ra172.

51 Morsut L, Roybal KT, Xiong X, et al. Engineering customized cell sensing and response behaviors using synthetic notch receptors[J]. Cell,2016, 164(4):780-791.

52 Roybal KT, Rupp LJ, Morsut L, et al. Precision tumor recognition by T cells with combinatorial Antigen-Sensing circuits[J]. Cell, 2016,164(4):770-779.

53 Greco R, Oliveira G, Stanghellini MT, et al. Improving the safety of cell therapy with the TK-suicide gene[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2015, 6:95. 54 Ma JS, Kim JY, Kazane SA, et al. Versatile strategy for controlling the specificity and activity of engineered T cells[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016, 113(4):E450-E458.

55 Rodgers DT, Mazagova M, Hampton EN, et al. Switch-mediated activation and retargeting of CAR-T cells for B-cell malignancies[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016, 113(4):E459-E468.

56 Wu CY, Roybal KT, Puchner EM, et al. Remote control of therapeutic T cells through a small molecule-gated chimeric receptor[J]. Science,2015, 350(6258):aab4077.

57 Juillerat A, Marechal A, Filhol JM, et al. Design of chimeric antigen receptors with integrated controllable transient functions[J]. Sci Rep,2016, 6:18950.

58 He SZ, Busfield S, Ritchie DS, et al. A phase 1 study of the safety,pharmacokinetics and anti-leukemic activity of the anti-CD123 monoclonal antibody CSL360 in relapsed, refractory or high-risk acute myeloid leukemia[J]. Leuk Lymphoma, 2015, 56(5):1406-1415.

59 Nievergall E, Ramshaw HS, Yong AS, et al. Monoclonal antibody targeting of IL-3 receptor α with CSL362 effectively depletes CML progenitor and stem cells[J]. Blood, 2014, 123(8):1218-1228.

60 Busfield SJ, Biondo M, Wong M, et al. Targeting of acute myeloidleukemia in vitro and in vivo with an anti-CD123 mAb engineered for optimal ADCC[J]. Leukemia, 2014, 28(11):2213-2221.

61 Chichili GR, Huang L, Li H, et al. A CD3xCD123 bispecific DART for redirecting host T cells to myelogenous leukemia: preclinical activity and safety in nonhuman primates[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2015,7(289):289ra82.

62 Kügler M, Stein C, Kellner C, et al. A recombinant trispecific singlechain Fv derivative directed against CD123 and CD33 mediates effective elimination of acute myeloid leukaemia cells by dual targeting[J]. Br J Haematol, 2010, 150(5):574-586.

63 Yc S, Erik P, Hsing C, et al. Immunotherapy with Long-Lived Anti-CD123×Anti-CD3 Bispecific Antibodies Stimulates Potent T Cell-Mediated Killing of Human AML Cell Lines and of CD123+Cells in Monkeys:A Potential Therapy for Acute Myelogenous Leukemia[J]. Blood, 2014, 124(21):2316-2316.

64 Mardiros A, Dos Santos C, Mcdonald T, et al. T cells expressing CD123-specific chimeric antigen receptors exhibit specific cytolytic effector functions and antitumor effects against human acute myeloid leukemia[J]. Blood, 2013, 122(18):3138-3148.

65 Peinert S, Prince HM, Guru PM, et al. Gene-modified T cells as immunotherapy for multiple myeloma and acute myeloid leukemia expressing the Lewis Y antigen[J]. Gene Ther, 2010, 17(5):678-686.

66 Lynn RC, Feng Y, Schutsky K, et al. High-affinity FRβ-specific CAR T cells eradicate AML and normal myeloid lineage without HSC toxicity[J]. Leukemia, 2016, 30(6):1355-1364.

Chimeric Antigen Receptor-modifying Tagainst CD123 for the treatment of AML

Sun Yao,Zhang Bin, Chen Hu. Department of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation, Affiliated Hospital & Cell and Gene Therapy Center, Academy of Military Medical Sciences, Beijing 100071, China

s: Chen Hu, Email:chenhu217@aliyun.com; Zhang Bin, Email:zb307ctc@163. com

Acute myeloid leukemia(AML)is a refractory hematologic malignancies which still lacks a good prognosis and craves a new treatment. With the progress of the chimeric antigen receptor-modifying(CAR)T cell(CAR-T)technology and the achievement got on the B-cell malignancies,an increasing targets are been investigated, ranging from kinds of hematology to solid tumors. CD123 molecule is a potential target of leukemia stem cells(LSCs)and leukemia blasts,while anti-CD123 CAR-T has the ability to clear the AML leukemia stem cells(LSCs)and blasts. We summarize the current progress and the direction about the treatment of anti-CD123 CAR-T.

Leukemia; Acute; Antigen; Receptor; Stem cells; Interleukin-3 Receptor alpha Subunit; T cells

2016-02-21)

(本文编辑:蔡晓珍)

10.3877/cma.j.issn.2095-1221.2016.03.009

100071 北京,军事医学科学院附属医院造血干细胞移植科 军事医学科学院细胞与基因治疗中心

陈虎,Email:chenhu217@aliyun.com;张斌,Email:zb307ctc@163.com

孙耀, 张斌, 陈虎. 靶向CD123抗原嵌合受体T细胞治疗急性髓系白血病的研究[J/CD].中华细胞与干细胞杂志:电子版,2016, 6(3):184-190.