技术美学与生命寓言

——对新媒体艺术家徐文恺及个展“不确定”的观察和误读

2016-04-14艾姝

艾 姝

技术美学与生命寓言

——对新媒体艺术家徐文恺及个展“不确定”的观察和误读

艾 姝

编者按:艺术家徐文恺学计算机出身,长于通过数据处理及信息过滤,在他的创作中极大限度地运用建筑、电子音乐、表演、产品设计、医学等跨领域的语言,展现了当今这个网络技术发达的时代,成长于媒体之下的青年艺术家对艺术“不确定性”的理解与表现。

Editor’s note:The artist Xu Wenkai, who majored in computer science when at university, is good at data processing and information fltering. In his creation, he makes the most of the interdisciplinary language of architecture, electronic music, performance, product design and medicine to demonstrate a young artist’s understanding and expression of“uncertainty” of art in this age characterized by developed Internet technology.

图1 徐文恺 从左至右 Untitled,Untitled 0,Untitled 2 视频装置 LCD显示器,亚克力组件 16×24×3.4/件,04:00左右3件 2015年Fig. 1 Xu Wenkai, (from left to right) Untitled, Untitled 0, Untitled 2, video installation, LCD Screen, Acrylic Fittings, 16×24×3.4 cm each piece, 2015

图2 徐文恺 《Untitled》的展览现场Fig. 2 Exhibition view of Xu Wenkai’sUntitled

2015年的最后一天,在北京雾霾弥漫的空气中,观众进入到798艺术区杨画廊的展示空间,心情可能会从雾霾导致的“紧张档”调换到“轻松档”。因为艺术家徐文恺在个展“不确定”中,讨论了“新生命”——与网络信息和生物技术、太空探索、环境污染等时代背景紧密关联的论题。

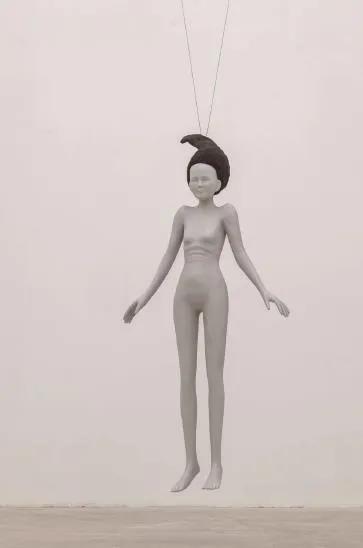

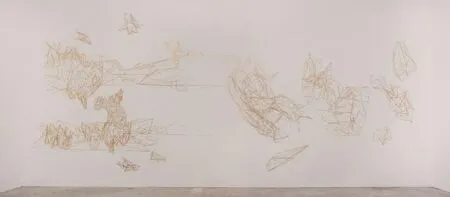

第一个6平方米左右的纯白空间中只有三个小屏幕,其中分别“浮动”着用计算机绘制的头部、手和头骨的特写镜头(图1、图2)。三个小屏幕簇拥在一面墙的一角,而其余三面墙上没有任何图像,有待想象。第二个纯白空间比第一个更为高大,四个造型相近的灰色瘦长“人体”悬浮着(图3、图4)组成第二件作品。它们是之前小屏幕展示的头部和手部图像的“实体”。每个实体的脖子后部都有一个“文身”(图5、图6),这就是“未来人”区别于彼此的唯一身份符号。在悬浮的人体后,墙面上类似于身份符号的放大版图形构成了背景——此为第三件作品(图7—图9)。金色的铜线像蜘蛛网一样“附着”在白色墙面上。远看过去,这些线条构成体仿佛悬浮在白色的“悬置空间”中。这面暗示悬置空间的墙面,是从计算机虚拟空间向真实三维空间的延伸和过渡,不仅是空间背景,也是叙事背景:二维与三维、虚拟与实体的转换通道。第四件作品被安置在此展厅入口的右侧墙角,是通过3D打印技术制作的头骨(图10)。它是第一个展厅中小屏幕上所展示头骨的实体。头骨的后侧明显泛黄,这是作者刻意将它放到窗边曝晒的结果。所有这些作品都没有放置标签,观众看到的正是一些“不确定”的、有待进一步想象的概念作品。

展厅二层,陈列着一件老作品《Meta》(2013年,图11—图13),这也是徐文恺本次展览作品的构想基础,它勾勒出理解一层四件新作品的关键语境。一切从计算机运算开始,创作者编定基本的规则,后面的运算自发地持续下去,并根据参数变化产生超出预设的图像——带领我参观的画廊工作人员根据自己的理解,向我如此“转述”了作品的意义。于是,我理解这件作品的底层数据应该类似于著名的约翰·康威“生命起源”程序,其基本规则是:棋盘一样的格子,亮为“生”,灭为“死”,灭的格子周围的八个格子中只要有三个格子亮着,则中心的这个格子会亮起来,意味着生;如果亮着的格子周围的八个格子中有四个及以上的格子亮着,则中心这个格子会因为“拥挤”致死而灭掉。这是一个类似于丢下种子就自发开始的细胞复制过程。《Meta》这段不断变化的图像中,有类似于展览空间一层的未来人身份符号的图形,它们也类似于暗示“悬置空间”的墙面上的图形结构——展览中各个作品的意义就基于如福柯指出的那种“近似”。尽管整个叙事可能存在思维断裂,但这些未来人的样态应与《Meta》中的数据繁殖、进化有关,至少它们的身份符号暗示出这种渊源。当然,以这套运算进行下去,未来人的样态也可能是那个骷髅的样子,所以一切仍旧“不确定”。

On the last day of 2015, in the hazy air in Beijing, when the viewers entered the exhibition space of Yang Gallery of 798 Art District, they might feel relaxed after experiencing haze-caused nervousness. For in his solo exhibition “Uncertain”, the artist Xu Wenkai tried to discuss “new life”, a topic closely related to the background of this era, such as network information, biotechnology, space exploration, and environmental pollution.

In the frst space, a pure white space of about 6 m2, there were only three small screens, on which close-up shots of a head, a hand and a skull drawn by computer were “foating” respectively (fgs. 1, 2). The three small screens clustered closely on the corner of a wall while the other three walls were blank for imagination. The second pure white space was bigger and taller than the frst, where four suspending grey and thin“human bodies”, similar in form, constituted the second work (fgs. 3, 4). They were actually the “real objects” of the head and the hand shown on the small screens in the frst work. On the back of the neck of each real object there was a “tattoo” (fgs. 5, 6), the only identity mark of the“future human beings” that could differentiate them from one another. Behind the suspending bodies, the enlarged pattern of something like identity mark on the wall constituted the background, and it was the third work (fgs. 7-9). Golden copper wires were attached to the white wall like spider webs. Seen in the distance, these wires seemed suspending in a white “suspending space”. This wall, suggestive of a suspending space, was the extension and transition from the computer’s virtual space to the real three-dimensional space. It was not only a spatial background, but also a narrative one: a transitional channel from the two-dimensional to the three-dimensional and from the virtual to the real. The fourth work, placed at the right corner beside the entrance to the exhibition hall, was a skull made by means of 3D printing technology (fg. 10). It was the real object of the skull shown on one of the three small screens in the frst exhibition room. The back of the skull was obviously yellowing as the result of being exposed to the sun at the window by the artist deliberately. As none of the four works had a tag, what the viewers saw was “uncertain”conceptual works for further imagination.

On the second foor of the exhibition hall, an old work titledMetawas displayed (2013, fgs. 11-13), which also served as the basis for Xu Wenkai’s conception of the exhibits. It offered a key to understanding the four new works exhibited on the first floor. All started from computer calculation, and the basic regulation was laid down by the creator. Subsequent calculations continued spontaneously and generated unexpected images according to parametric variation. A gallery staff member paraphrased the above meaning of the work to me according to his own understanding while guiding me through the exhibition. Therefore, I realized that the underlying data of the work resembled that of the program “Game of Life”, designed by John Conway. Its basic rules were as follows. The bright squares of something like chessboard meant “alive” while the dark ones, “dead”. If three of the eight squares that surrounded a dark square were bright, then the central square would become bright, meaning “alive”; if four or more of the eight squares that surrounded a bright square were bright, then the central square would become dark because of crowdedness. This was like the spontaneous process of cell replication caused by a seed. Among the ever-changing images ofMetaare those resembling the identity marks of future human beings displayed on the first floor as well as the patterns on the wall suggestive of a “suspending space”. The meanings of the exhibits were based on the “resemblance” pointed out by Foucault. Although the whole narration might have fractures of thinking, the appearances of future human beings might have some link with the data replication and evolvement shown inMeta, or at least their identity marks implied such an origin. Certainly, if the calculation went on, future human beings might look like that skull and, therefore, everything was still “uncertain”.

徐文恺的教育背景与通常的艺术家有很大差异,他毕业于武汉大学计算机系。从本次展览的作品来看,有两个鲜明的特点。其一,思考的纬度上,他更观照技术哲学的相关问题。

图3 徐文恺 图腾 雕塑 树脂、海绵、金属结构 尺寸可变2015年Fig. 3 Xu Wenkai, Totem, sculpture, resin, sponge, metal structure, variable size, 2015

图4 徐文恺 图腾 雕塑 树脂、海绵、金属结构 尺寸可变2015年Picture 4 Xu Wenkai, Totem, sculpture, resin, sponge, metal structure, variable size, 2015

之前的作品中,他常常利用“机器”为媒介,探讨技术对于人和社会造成的影响;然而,从《Meta》开始,延续到这次个展的四件作品,他以技术制造现实的“镜像”,并从中思考生命规则、生命发展等问题,这里有其对技术反思的推进,从社会学思考转向更宏观的生命哲学命题。当然,他或许也回应着近年国内日益高涨的科幻热潮。本次徐文恺作品的另一个特点是,形式上根植于技术美学的维度。美学在当代艺术中的位置早已式微,当代艺术作品的成功更仰赖于主题的重要性和艺术家的洞见力;但“形式”仍是视觉艺术难以绕开的重要问题。徐文恺《Meta》以后的作品之所以可以被冠以“技术美学”,可以从作品的整体设计和制作的精细程度来理解。极简的、标准化的工业设计潮流,在个体身体特征几乎无法辨识的“未来人”身上得以体现,只有唯一的“文身”来区分彼此。而《Meta》中不断繁殖着的虚拟“生命形态”,其极简的线条通过数据运算形成千变万化的形式,引人联想到达·芬奇以数学规律捕获人体黄金比例的传奇事件——数与美,在人类历史中,长期孪生。《Meta》所开启的未来的可能世界中,“美”在计算机的数学运算中自然获得,那些如晶体的、玫瑰花朵的形状,都被数据运算处理得简洁而精致;其播放器(图11)则是一个由艺术家专门制作的木盒子,电路板被工整地装饰在盒子表面,兼具材质的美感和技术感,饱含对技术的爱与敬畏,与很多新媒体艺术家直接搬用电视、显示器等现成播放器的做法截然不同。而一层展厅中墙面上“悬浮”的金属图形,也是从计算机运算产生的图形中截取出来,再严格按照比例,从等大的铜板上切割出的二维实体。当然,上述这种借鉴现代科技和制造手段所诞生的艺术作品,并非只是徐文恺理科背景的体现,也是当前新媒体艺术所要求的技术能力和技术思维的体现,还是新媒体艺术复归到文艺复兴时期以达·芬奇为代表的科学与艺术结合实践传统的体现。

Xu Wenkai’s educational background differs a lot from those of other artists. He graduated from the Computer Engineering Department, Wuhan University. His works at the exhibition show two distinct characteristics. First, he is concerned more about philosophy of technology. In his former works, he often used “machines” as a medium to discuss the influence of technology on human beings and society. However, fromMetato the four works at this solo exhibition, he has produced “mirror images” of reality by means of technology, and refects on such issues as rules and development of life. Here his promotion of rethinking about technology and his turning from sociological considerations to the more macroscopic proposition of philosophy of life are implied. Of course, maybe he has done this as a reaction to the increasingly rising science fction rush in China in recent years. Another characteristic of Xu’s works is that they are based, in form, on technology aesthetics. Aesthetics has long suffered from a decline of its status in contemporary art, and the success of modern art works depend more on the importance of themes and the insight of artists. However, “form”is still an important element hard to bypass in visual art. The labelling of Xu Wenkai’sMetaand his later works as “technology aesthetics”can be understood from the perspective of the overall design and the elaborateness of making. The trend of Minimalist and standardized industrial design is embodied in future human beings whose individual features are too similar to differentiate. The only identity mark is the“tattoo”. The virtual “life form” in successive reproduction inMetais revealed in simple lines that varies with data operation, reminding people of the legendary event that Leonardo da Vinci acquired the golden ratio of human body by mathematical laws. Number and beauty have been twins throughout history. In the future possible world thatMetaopened up, “beauty” can be naturally acquired in computer calculation. Those shapes similar to crystalline rose petals look simple but fne after being processed by data operation. The player (fg. 11) is a wooden box specially made by the artist on the surface of which a circuit board is placed in a neat manner. This player, full of beauty of texture and sense of technology and with the love and awe for technology contained in it, is totally different from the ready-made players such as TV sets and monitors many new-media artists used directly. The “suspending” metal patterns on the wall of the frst-foor exhibition hall are two-dimensional solid structures, cut out of same-size copper plates according to a selected part of the pattern also generated from computer calculation in a certain proportion. Of course, the above-mentioned art works withmodern technology and methods used for reference are an embodiment of not only Xu Wenkai’s science background, but also the technical skills and technical thinking demanded by new media art, and moreover, the returning of new media art to the Renaissance tradition, represented by Leonardo da Vinci, of combining science with art.

图5 徐文恺 图腾(局部) 雕塑 树脂、海绵、金属结构尺寸可变 2015年Fig. 5 Xu Wenkai, Totem (detail), sculpture, resin, sponge, metal structure, variable size, 2015

图6 徐文恺 图腾(局部) 雕塑 树脂、海绵、金属结构尺寸可变 2015年Fig. 6 Xu Wenkai, Totem (detail), sculpture, resin, sponge, metal structure, variable size, 2015

从《Meta》到这次展览的“实物”作品《碎片》(图7)、《图腾》(图3—图6)、《存在》(图10),有一种从“数字”(digital)到“模拟”(analog)的转换。如前文所述,《碎片》展示了二者转换的通道。数字虚拟世界是由二进制(0和1)构成的整数的世界,可以被精确复制,不存在原本与复制本的本质区别;而模拟的世界是对现实的物理模仿,由连续的物理信号或物质构成的,如果复制,则会产生衰减和差异,则无法真正存在两件完全一样的事物。徐文恺将自己在数字世界中创造的形象制造为“实物”,别有意味:这是对数字世界的“虚拟物”反向“模拟”,此举并不能被简单地理解为类似动漫衍生品“手办”的形态。毕竟,徐文恺严格地规定这些未来人的外形为标准化、同一化的——排除现实世界中人造物必然的差异性——正像《存在》中的头骨,是被3D打印出来的虚拟产物的“精确”物理呈现。不过,作者也意识到了,一旦具有真实世界的形体,物体必然经历物理世界的改变,不再是虚拟世界中所设计的样子,因而他会把头骨置于阳光下曝晒。因而,徐文恺的试验通过“数字”造物与“模拟”造物的混合使用,探讨着世界的更丰富可能。

图7 徐文恺 碎片 装置 蚀刻铜片×59 尺寸可变 2015年Fig. 7 Xu Wenkai, Bits of Information, installation, etching copper plate×59, variable size, 2015

图8 展览“不确定”现场Fig. 8 View of the exhibition Untitled

图9 徐文恺 展览「不确定」现场Fig. 9 View of the exhibition Untitled

A transition from “digital” to “analog” exists betweenMetaand the “real object” works showcased at the exhibition, includingBits of Information(fg. 7),Totem(fgs. 3-6), andExist(fg. 10). As mentioned above,Bits of Informationshows the channel for the transition. The digital virtual world is a world of integers constituted by a binary system of 0 and 1, which can be precisely duplicated without the essential difference of the original and the duplicate. However, as the simulated world is a physical imitation of reality, constituted by continuous physical signals or materials, duplication will involve attenuation and variation. As a result, it is impossible to produce two totally identical things. There is a distinctive meaning in Xu Wenkai’s turning the images he created in the digital world into “real objects”: it is a reverse simulation of the virtual in the digital world. Works thus produced cannot be simply interpreted as “Garage Kits”, anime derivative products. After all, Xu Wenkai portrays those future human beings with strictly standardized and uniform appearances, in which the inevitable differences between man-made objects in the real world are eliminated, just like the skull inExist, which is the precise physical presentation,by 3D printing, of a virtual product. The artist has also realized, however, that once something is materialized, it must undergo changes in the physical world and no longer has the designed appearance in the virtual world. That’s why he exposed the skull to the sun. Therefore, by means of mixed use of “digital” and “simulative” creations, Xu, in his experiment, explores more possibilities of the world.

Certainly, from a more macroscopic perspective of human technology development, the above mentioned process from digital programming to real object manufacturing may be, to some extent, a metaphor of the working of genetic technology, a “life fable” supported by historical and realistic information. If we connect the genesis myth demonstrated byMetawith the future human beings inTotem, and suppose that the latter is the extension of the former (he has no means to truly simulate the process of producing human beings, but only hints at a connection through the similarity between the tattoos on future human beings’ bodies and the images of origin), then perhaps human beings would have proceeded from making tomb fgures in ancient times to the world myth of cloning Dolly and replicating human organs on the basis of biological technology, and eventually to producing human beings. Through the new “tailoring” of underlying genetic data, the fundamental genetic traits of biological entities are duplicated, screened, controlled, rewritten, and even created. The underlying data ofMetaare “genes”, and the artist’s intervention in data operation is “gene rewriting”. The various images we see at last are the “new lives after genetic manipulation”.

图10 徐文恺 存在 装置 3D打印、树脂 30×30×27cm 2015年Fig. 10 Xu Wenkai, Exist, sculpture, 3D printing, resin, 30×30×27 cm, 2015

当然,从更宏观的人类技术发展的语境中看,上述从数字编写到实体制造的过程,在某种程度上还可能隐喻着基因技术之所为,是有历史、现实信息作为支撑的“生命寓言”。若将徐文恺的《Meta》所演示的创世神话和他创造的《图腾》未来人联系起来,假设后者是前者的延续——他并没有能力真正模拟这个造人过程,但通过未来人身上文身与起源图像的相似性来暗示一种关联——那么人类或许已经从古代制造墓葬“人偶”的阶段,奔向基于生物技术的克隆多利羊、人类器官的生物复制,最终造人的现世神话。通过对底层基因数据的重新“裁剪”,生物实体的基因性状被复制、筛选、控制、改写甚至创造。《Meta》图像的底层数据就是“基因”,而作者对数据运算的干预就是“基因改写”,最终我们看到的各种图像形态就是“基因控制后的新生命”。

图11 徐文恺 Meta 视频装置 LCD显示器、电路板、木头组件 42.5×28×4.5cm 12’30” 2013年Fig. 11 Xu Wenkai, Meta, video installation, LCD screen, PCB, wood fttings, 42.5×28×4.5cm, 12’30” , 2013

图12 徐文恺 Meta 视频装置(截图) LCD显示器、电路板、木头组件 42.5×28×4.5cm 12’30” 2013年Fig. 12 Xu Wenkai, Meta, LCD screen, PCB, wood fttings, 42.5×28×4.5cm, 12’30” , 2013

2016年1月12日,笔者就本次个展的作品与徐文恺(网络代称:aaajiao)通过微信交流。在他自己看来,《Meta》是无意义的,它的存在是为了反对2013年时无论在现实社会还是新媒体艺术圈里都异常火爆的大数据及其视觉化呈现。这种无意义是要消解大数据可视化的伪命题。这件作品的数据程序由徐文凯及其团队编写,具体的参数变化则来自徐文恺手动控制的MIDI设备,即物理的、模拟样式的机器。如此,数据演算的程序模式是数字形态的自发运算,而MIDI杠杆的调整是人为随机制造的“模拟”形式的信息,最终的作品视觉效果更为丰富,也无法被精确复制。最终,在Meta这个模型中,输入数据所产生的图像什么也说明不了,意义被消解。他希望作品要与别人的做法不同,要有视觉特色,也要具有开放性。这就是徐文恺告诉我的关于《Meta》创作的“本意”。而在笔者眼里,如前文所述,《Meta》让我想起了著名的约翰·康威“生命起源”程序,与他的本意有极大出入,自然笔者基于此对整个展览的解读也显示为“误读”——不过,徐文恺“不确定”展中的这四件新作的确是基于《Meta》展开的。我并没有告诉他我的解读,只是在听到他的原意之后告诉他:一、画廊提供了与他不一样的信息;二、艺术作品的传播需要意义。他就此点的回应是,他并不排斥不同身份的观众根据自己经验对作品意义的解释——正因为作品是开放的,才会激发观众不同的解读,这正是他认为开放性作品的有趣之所在。

图13 徐文恺 Meta 视频装置(截图) LCD显示器、电路板、木头组件 42.5×28×4.5cm 12’30” 2013年Fig. 13 Xu Wenkai, Meta, LCD screen, PCB, wood fttings, 42.5×28×4.5cm, 12’30” , 2013

On January 12, 2016, I communicated on Wechat with Xu Wenkai (net name: aaajiao) about the exhibits. According to him,Metais meaningless. He created it as an act of opposition to the big data and itsvisual appearance which was really hot in society and the new media art circles in 2013. The meaninglessness was aimed to destruct the pseudoproposition of big data visualization. The data program of the work was written by Xu Wenkai and his team. The specifc parametric variation came from the MIDI equipment, a type of physical and simulative equipment, manually controlled by Xu Wenkai,. The program mode of data calculation was spontaneous operation in digital form while the MIDI lever was adjusted by simulative information randomly generated. The final work had richer visual effects which could not be exactly duplicated. InMeta, the images generated after data input meant nothing. Xu Wenkai hoped that his works, with their visual features and openness, could be distinct from those by other artists. This was what Xu Wenkai told me about the original idea ofMeta. As mentioned above,Metareminded me of the famous program of “Game of Life” by John Conway, quite inconsistent with Xu Wenkai’s own interpretation of the work. Therefore, I naturally misread the exhibition. However, the four new works in “Uncertain” were indeed created on the basis ofMeta. I didn’t tell the artist about my interpretation, but only told him after learning his original intention: 1. The gallery provided different information. 2. Meaning is needed in the spreading of art works. In response, he said that he would not reject interpretations of the meanings of his works by different viewers according to their own experiences. It is the openness of works that stimulates the viewers’different interpretations, and just here lies, in his view, the interest of open works.

艾 姝:天津美术学院学报编辑

Ai Shu: editor of the Journal of Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts

Technology Aesthetics & Life Fable: Observation and Misreading of New Media Artist Xu Wenkai and His Exhibition “Uncertain”

/Ai Shu