食品中多酚形态的研究进展

2015-11-02颜才植叶发银赵国华

颜才植,叶发银,赵国华,2,*

(1.西南大学食品 科学学院,重庆 400715;2.重庆市特色食品工程技术研究中心,重庆 400715)

食品中多酚形态的研究进展

颜才植1,叶发银1,赵国华1,2,*

(1.西南大学食品 科学学院,重庆 400715;2.重庆市特色食品工程技术研究中心,重庆 400715)

近年来,植物多酚因其存在的普遍性、对食品品质形成的重要性以及众多的生理活性,已成为食品科学和营养学研究的一个热点。多酚以游离态和结合态两种形态存在于食品中。大量研究表明,植物多酚对食品 品质及健康功能的贡献,不仅取决于其种类和数量,而且取决于其在食品基质中的存在形态。本文在广泛调研文献的基础上,对食品中多酚形态,不同形态多酚的分析方法,常见食品(谷物、水果、蔬菜、可食花卉、其他食品)中游离态多酚与结合态多酚的含量,以及食品加工对多酚形态的影响进行总结,并对食品中多酚形态研究存在的问题及其发展方向进行阐述。

游离态多酚;结合态多酚;形态;分析;加工

多酚(polyphenols)是广泛存在于可食性植物组织中的一类植物化学物质(phytochemicals),它被证实具有抗氧化活性,能有效预防高血脂、高血糖、心脑血管疾病、肿瘤等慢性疾病。近20 年来,在食品营养学和预防医学领域,大量研究表明,多酚对人体健康的促进作用不仅与多酚在食品中的种类和数量相关,而且与其在食品基质中的存在形态密切相关。其存在形态甚至影响到我们对多酚在食品中的种类和数量的定量分析。过去大多数测定多酚含量的方法是采用溶剂直接萃取后进行定量分析。此法只能测定可萃取多酚,对于那些与食品基质结合紧密的多酚则无法测定,因此测定结果往往明显低于其实际含量。Krygvier等[1]率先提出结合态多酚的概念,即需要通过碱水解才能萃取的多酚。Krygier等提供了精确测定游离态多酚和结合态多酚的方法,其研究被人们广泛重视,结合态多酚逐渐成为多酚研究的一个重要方面[2-4]。多酚形态与其健康效应的关系以及通过加工改变多酚形态以提升其生物利用度的研究已有大量报道和综述,本文不再赘述;而有关食品中不同形态多酚的比例以及加工对其形态变化的影响规律方面的研究较为薄弱,因此本文对食品中多酚的存在形态、分析方法,以及加工对多酚形态的影响进行综述,以期为膳食多酚对食品品质形成影响的深入研究提供参考。

1 食品中多酚的形态及其分析方法

1.1食品中多酚形态的划分

多酚在食品基质中的存在形式即为多酚的形态,食品多酚的形态对于其溶解性、可萃取性、生物活性、人体利用度以及在食品中的应用等方面都有重要的影响。可根据多酚的存在形态将其分为游离态多酚和结合态多酚。游离态多酚是以单体形式被物理吸附或截留于食品基质中的多酚,其游离形态表现出了良好的溶解性,易溶于水或有机溶剂。结合态多酚是经由共价键与食品基质(如细胞壁物质)相结合的多酚,具有难萃取的特点。食品中与多酚结合的细胞壁物质主要包括木聚糖(存在于小麦[2]、玉米[2]、大麦[2]等)、阿拉伯木聚糖(存在于甜菜[3]、玉米皮[3]等)、纤维素(存在于甜菜[3]、玉米皮[3]等)、木质素(存在于竹笋[4]等)、果胶(存在于菠菜[5]、甜菜[5]等)、半纤维素(存在于麸皮[4]等)和某些蛋白质(存在于玉米皮[3]、谷粒[4]等)。粮谷类食品中的结合态多酚研究报道较多,主要包括阿魏酸、香豆酸、羟基肉桂酸、可水解单宁等与多糖类物质共价结合的酚酸类物质。

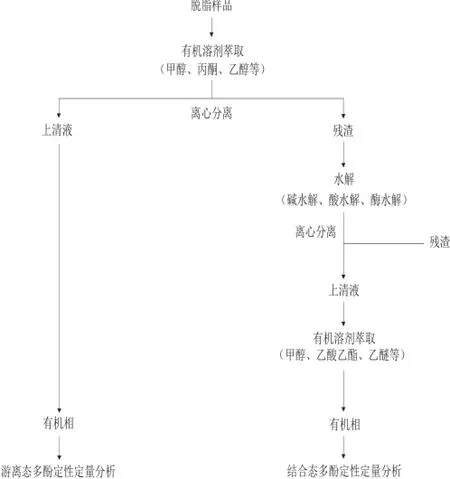

1.2食品中多酚形态的分析

食品中的游离态多酚可通过选择合适的溶剂直接萃取后进行定量(比色法或色谱法)分析,而结合态多酚由于被细胞壁物质束缚而无法被溶剂直接萃取。故结合态多酚只有先采用合适的水解方式(碱、酸、酶)使其释放为游离态再进行萃取分析。因此,食品中多酚形态的分析流程一般分为两步:一是目标对象经干燥脱脂后直接使用适当溶剂萃取,萃取液用于分析游离态多酚;二是对残渣进行适当水解,释放出结合态多酚再对其进行萃取分析。

水解释放是结合态多酚分析的关键步骤,常用的水解方法包括碱水解、酸水解和酶水解。酸水解主要是通过破坏糖苷键来释放结合态多酚,但不能释放通过酯键结合的多酚;同时酸水解往往需要较高的温度,这会导致多酚发生降解而流失。而碱水解可在室温条件下进行,多酚降解流失少,并且能同时释放通过糖苷键和酯键而结合的多酚[6]。目前报道的碱水解的文献数量远远多于酸水解和酶水解的数量,但没有确凿证据评定何种方法更好。在结合态多酚的分析研究中,碱水解的使用频率明显高于酸水解,尤其是谷物中结合态多酚的测定一般都采用碱水解方式。Krygier等[1]发现酸水解可导致玉米中酚酸的损失高达78%,而碱水解的只有4.8%。酶水解由于酶的特异性原因,其普适性较差,常用的酶包括β-葡萄糖氧化酶、淀粉酶、果胶酶、纤维素酶、半纤维素酶、细胞壁降解酶等[7-8]。商业果胶酶和酯酶制剂已经应用于甜菜渣中的结合态多酚的水解[9],木聚糖酶和酯酶被用于大麦中的酚酸提取[10]。Zheng Huzhe等[8]使用纤维素酶、β-葡聚糖酶、半纤维素酶、木聚糖酶等一系列碳水化合物酶提取青苹果中的多酚,其中香豆酸,阿魏酸和咖啡酸的提取量较非酶水解空白组分别提高了8、4、32 倍。图1给出了食品中多酚形态分析常用的流程。

图1 食品中多酚形态分析的常用流程Fig.1 General analysis procedures for polyphenol forms in foods

2 常见食品中多酚的形态分布

2.1谷物食品

由表1可知,除Shao Yafang等[11]报道的3 种大米,Chandrasekara等[12]报道的5 种粟(黍)以及Alu'datt等[13]报道的亚麻仁与大豆外,其他粮谷类食物中结合态多酚的含量都明显高于游离态多酚,尤其是玉米及小麦产品中,大多数分析结果都表明其结合态多酚占总多酚的比例超过了90%,有的甚至达到了99.8%[14]。但同时也发现,对不同来源的同一种食物的分析结果存在较大差异,如在玉米籽粒中,Gutiérrez-Uribe[15]和Irakli[16]等的结果表明,游离酚的含量占总多酚的比例在0.5%~0.8%之间,Adom等[17]的结果却高达13.6%,这可能与样品来源及分析操作方法有密切关系。

表1 谷物类食品中游离态多酚与结合态多酚的含量及比例Table 1 Contents and percentages of free and bound polyphenols in cereals

2.2水果

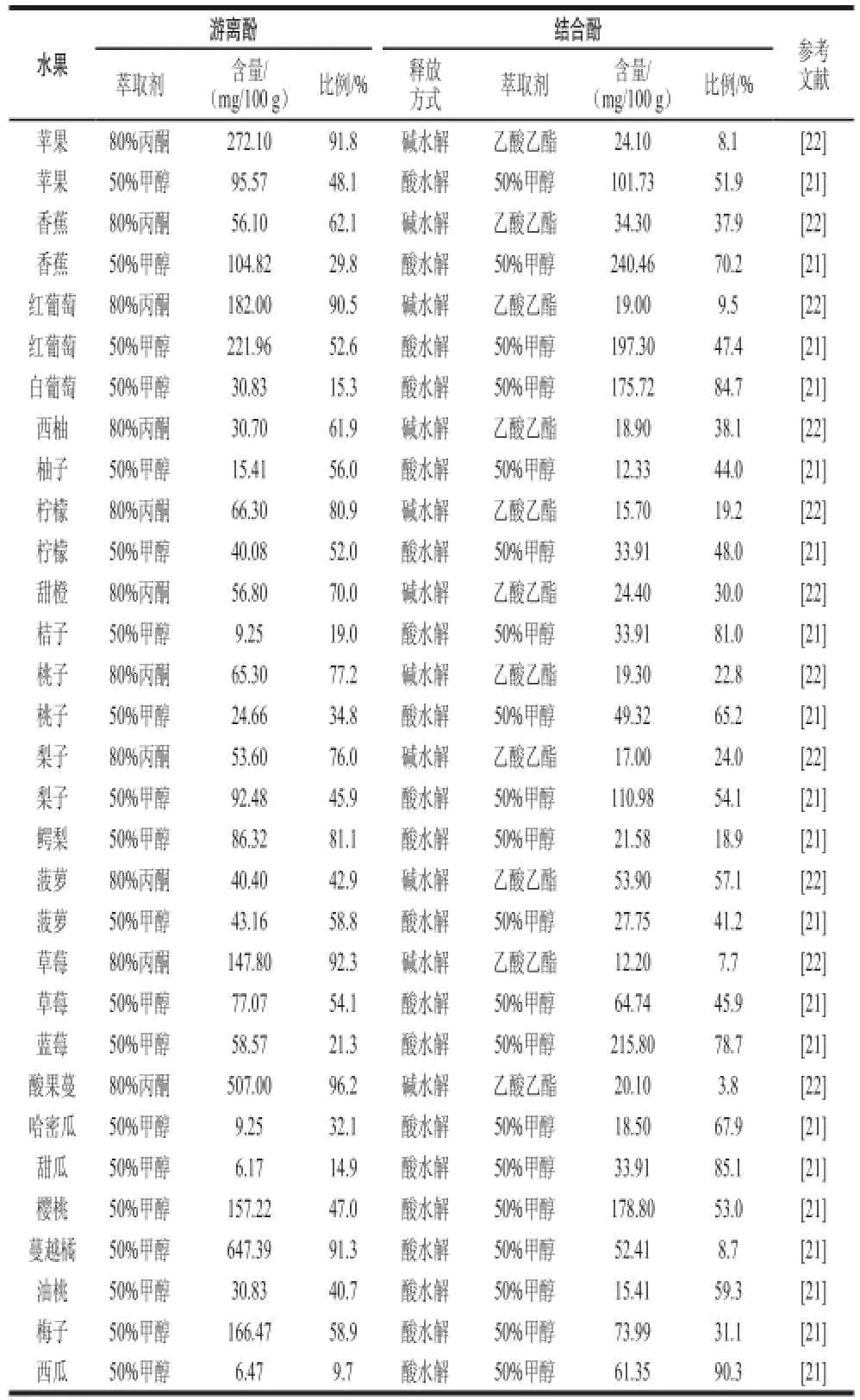

表2给出了常见水果中游离态多酚与结合态多酚的含量与比例。除了Vinson等[21]报道的香蕉、蓝莓、哈密瓜、樱桃、白葡萄、甜瓜、油桃、桔子外,其他水果中游离态多酚含量均高于结合态多酚,尤其是在一些颜色较深或酸涩味较重的水果中,分析结果表明其游离态多酚占总多酚的比例可超过90%。对不同来源的同一种水果的分析结果也存在着差异。对比Vinson[21]和Sun Jie[22]等的结果发现,苹果、香蕉、梨子、柠檬、草莓、桃子在多酚的含量或比例上有明显的差异,但对于菠萝分析结果的差异就很小。笔者推测造成此情况的原因可能与品种、来源、贮藏或分析过 程中的多酚降解、分析方法(如水解方式等)的不同有关。

表2 常见水果中游离态多酚与结合态多酚含量及比例Table 2 Contents and percentages of free and bound polyphenols in common fruits uits

2.3蔬菜

表3给出了常见蔬菜类食物中游离态多酚与结合态多酚的含量与比例。各种蔬菜的食用部分不同,由表3可知,花、叶相比于根、茎是多酚更易富集的部位。Hervert-Herná ndez[23]和Albishi[24]等的报道都说明了品种对于蔬菜中多酚的含量和比例有着重要的影响。同时,同一种蔬菜的不同组织中的多酚含量差异明显[24-27]。

表3 常见蔬菜中游离态多酚与结合态多酚的含量及比例Table 3 Contents and percentages of free and bound polyphenols in common vegetables

2.4可食花卉

表4给出了Kaisoon等[31]研究的一些可食花卉中的游离态多酚与结合态多酚的含量与比例。由表4可知,大部分可食花卉中的多酚含量都不高,并且在比例分布上并无明显的规律。可食花卉是一种潜力巨大的食品原料,但对其多酚等活性成分的研究还需进一步深入。

表4 常见可食花卉中游离态多酚与结合态多酚的含量及比例Table 4 Contents and percentages of free and bound polyphenols in some edible flowers

2.5其他食品

表5给出了一些食物中游离态多酚与结合态多酚的含量与比例。Gruz等[32]的结果显示,枸杞在生长过程中,游离态多酚含量几乎没有变化,但结合态多酚含量却逐渐降低。Chandrasekara等[33]的研究结果说明同一食品原料的不同部位的多酚含量可能存在巨大差异,这与表4中呈现的结果一致。

表5 其他食物中游离态多酚与结合态多酚的含量及比例Table 5 Contents and percentages of free and bound polyphenols in some other foods

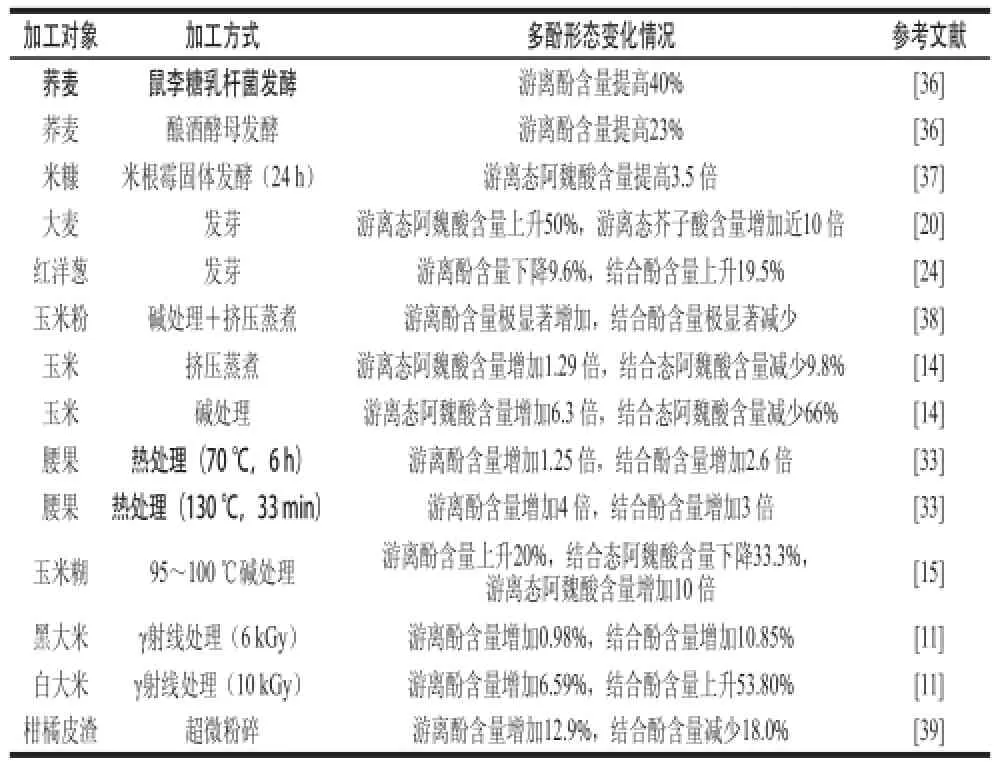

3 加工对食品中多酚形态的影响

有大量研究报道表明,多种加工处理方式对食品中的多酚形态往往具有显著影响。在大多数情况下,食品加工处理能使结合态多酚部分转化为游离态多酚,从而使游离态多酚含量上升而使结合态多酚含量下降。究其原因,主要是在食品加工过程中由于酸水解、碱水解、酶水解、热降解、机械化作用等使多酚与细胞壁物质之间的共价作用或非共价作用解除,而导致结合态多酚向游离态多酚转化。糙米在不同温度条件下贮藏会导致其中的多酚形态发生不同的变化。37 ℃条件下贮藏6 个月的实验发现糙米中结合酚比例由32%降至29%。游离态阿魏酸含量几乎不变,结合态阿魏酸含量下降13%;游离态香豆酸含量增加1 倍,结合态对香豆酸含量下降37%;游离态没食子酸含量增加5 倍,结合态没食子酸几乎全部消失;游离态香草酸含量有所增加,结合态香草酸含量下降超过50%。而低温(4 ℃)贮藏6 个月糙米中结合酚比例由32%下降至31%。游离态阿魏酸含量略微上升,结合态阿魏酸含量下降12%;游离态香豆酸含量增加2.4 倍,结合态对香豆酸含量减少33.3%;游离态没食子酸含量增加6 倍,结合态没食子酸几乎全部消失;游离态香草酸含量略有增加,结合态香草酸含 量下降超过50%[19]。表6给出了一些常见食品加工方式对多酚形态的影响。

表6 加工处理对食品中多酚形态的影响Table 6 Effect of food processing on forms of polyphenols

4 结 语

综上所述,食品多酚形态的研究近年来取得了快速的进步与质的飞跃,尤其在多酚形态的定义、分析、各类食品中不同形态多酚的含量普查等多方面有了快速的积累。结合当前的研究状况,后续有关食品中多酚形态的研究可从以下几个方面加强或深入:1)更为标准化的多酚形态分析方法的研究;2)食品原料生产的环境条件(如干旱、肥料等)对农产品中多酚形态及含量的影响;3)食品及其原料在贮藏和加工过程中多酚形态的变化需进一步深入,并明确其变化的机制;4)游离态多酚与结合态多酚在发挥生物活性方面的相互作用机制(协同增效);5)食品中多酚形态的调节技术与方法研究。

[1] KRYGIER K, SOSULSKI F, HOGGE L. Free, esterified, and insoluble-bound phenolic acids. 1. Extraction and purification procedure[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 1982,30(2): 330-334.

[2] WONG D W S. Feruloyl esterase[J]. Applied Biochemistry and Biotech nology, 2006, 133(2): 87-112.

[3] SAULNIER L, THIBAULT J F. Ferulic acid and diferulic acids as components of sugar-beet pectins and maize bran heteroxylans[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 1999, 79(3): 396-402.

[4] LIYANA-PATHIRANA C M, SHAHIDI F. Importance of insolublebound phenolics to antioxidant prop erties of wheat[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2006, 54(4): 1256-1264.

[5] COLQUHOUN I J, RALET M C, THIBAULT J F, et al. Structure identification of feruloylated oligosaccharides from sugar-beet pulp by NMR spectroscopy[J]. Carbohydrate Research, 1994, 263(2): 243-256.

[6] KIM K H, TSAO R, YANG R, et al. Phenolic acid profiles and antioxidant activities of wheat bran extracts and the effect of hydrolysis conditions[J]. Food Chemistry, 2006, 95(3): 466-473.

[7] LANDBO A K, MEYER A S. Enzyme-assisted extraction of antioxidative phenols from black currant juice press residues (Ribes nigrum)[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2001, 49(7):3169-3177.

[8] ZHENG Huzhe, HWANG I W, CHUNG S K. Enhancing polyphenol extraction from unripe apples by carbohydrate-hydrolyzing enzymes[J]. Journal of Zhejiang University: Science B, 2009, 10(12):912-919.

[9] FAZARY A E, JU Y H. Feruloyl esterases as biotechnological tools:current and future perspectives[J]. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica, 2007, 39(11): 811-828.

[10] SANCHO A I, BARTOLOM☒ B, G☒MEZ-CORDOV☒S C, et al. Release of ferulic acid from cereal residues by barley enzymatic extracts[J]. Journal of Cereal Science, 2001, 34(2): 173-179.

[11] SHAO Yafang, TANG Fufu, XU Feifei, et al. Effects of γ-irradiation on phenolics content, antioxidant activity and physicochemical properties of whole grainrice[J]. Radiation Physics and Chemistry,2013, 85: 227-233.

[12] CHANDRASEKARA A, SHAHIDI F. Content of insoluble bound phenolics in millets and their contribution to antioxidant capacity[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2010, 58(11): 6706-6714.

[13] ALU'DATT M H, RABABAH T, EREIFEJ K, et al. Phenolic: protein interactions in oilseed protein isolates[J]. Food Research International,2013, 52(1): 178-184.

[14] MORA-ROCHIN S, GUTI☒RREZ-URIBE J A, SERNASALDIVAR S O, et al. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of tortillas produced from pigmented maize processed by conventional nixtamalization or extrusion cooking[J]. Journal of Cereal Science,2010, 52(3): 502-508.

[15] GUTI☒RREZ-URIBE J A, ROJAS-GARC☒A C, GARC☒A-LARA S,et al. Phytochemical analysis of wastewater (nejayote) obtained after lime-cooking of different types of maize kernels processed into masa for tortillas[J]. Journal of Cereal Science, 2010, 52(3): 410-416.

[16] IRAKLI M N, SAMANIDOU V F, BILIADERIS C G, et al. Development and validation of an HPLC-method for determination of free and bound phenolic acids in cereals after solid-phase extraction[J]. Food Chemistry, 2012, 134(3): 1624-1632.

[17] ADOM K K, LIU Ruihai. Antioxidant activity of grains[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2002, 50(21): 6182-6187.

[18] LOPEZ-MARTINEZ L X, OLIART-ROS R M, VALERIO-ALFARO G, et al. Antioxidant activity, phenolic compounds and anthocyanins content of eighteen strains of Mexican maize[J]. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2009, 42(6): 1187-1192.

[19] ZHOU Zhongkai, ROBARDS K, HELLIWELL S, et al. The distribution of phenolic acids in rice[J]. Food Chemistry, 2004, 87(3):401-406.

[20] DVOŘ☒KOV☒ M, GUIDO L F, DOST☒LEK P, et al. Antioxidant properties of free, soluble ester and insoluble-bound phenolic compounds in different barley varieties and corresponding malts[J]. Journal of the Institute of Brewing, 2008, 114(1): 27-33.

[21] VINSON J A, SU Xuehui, ZUBIK L, et al. Phenol antioxidant quantity and quali ty in foods: fruits[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2001, 49(11): 5315-5321.

[22] SUN Jie, CHU Yifang, WU Xianzhong, et al. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of common fruits[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2002, 50(25): 7449-7454.

[23] HERVERT-HERNÁNDEZ D, SÁYAGO-AYERDI S G, GONI I. Bioactive compounds of four hot pepper varieties (Capsicum annuum L.),antioxidant capacity, and intestinal bioaccessibility[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2010, 58(6): 3399-3406.

[24] ALBISHI T, JOHN J A, AL-KHALIFA A S, et al. Antioxidative phenolic constituents of skins of onion varieties and their activities[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2013, 5(3): 1191-1203.

[25] AYAZ F A, HAYIRLIOGLU-AYAZ S, ALPAY-KARAOGLU S, et al. Phenolic acid contents of kale (Brassica oleraceae L. var. acephala DC.) extracts and their antioxidant and antibacterial activities[J]. Food Chemistry, 2008, 107(1): 19-25.

[26] HARBAUM B, HUBBERMANN E M, ZHU Zhujun, et al. Free and bound phenolic compounds in leaves of pak choi (Brassica campestris L. ssp. chinensis var. communis) and Chinese leaf mustard (Brassica juncea Coss)[J]. Food Chemistry, 2008, 110(4): 838-846.

[27] GUTI☒RREZ-URIBE J A, ROMO-LOPEZ I, SERNA-SALD☒VAR S O. Phenolic composition and mammary cancer cell inhibition of extracts of whole cowpeas (Vigna unguiculata) and its anatomical parts[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2011, 3(4): 290-297.

[28] CHU Yifang, SUN Jie, WU Xianzhong, et al. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of common vegetables[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2002, 50(23): 6910-6916.

[29] PERIČIN D, KRIMER V, TRIVIĆ S, et al. The distribution of phenolic acids in pumpkin's hull-less seed, skin, oil cake meal,dehulled kernel and hull[J]. Food Chemistry, 2009, 113(2): 450-456.

[30] NACZK M, WANASUNDARA P, SHAHIDI F. Facile spectrophotometric quantification method of sinapic acid in hexaneextracted and methanol-ammonia-water-treated mustard and rapeseed meals[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 1992, 40(3):444-448.

[31] KAISOON O, SIRIAMORNPUN S, WEERAPREEYAKUL N, et al. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of edible flowers from Thailand[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2011, 3(2): 88-99.

[32] GRUZ J, AYAZ F A, TORUN H, et al. Phenolic acid content and radical scavenging activity of extracts from medlar (Mespilus germanica L.) fruit at different stages of ripening[J]. Food Chemistry,2011, 124(1): 271-277.

[33] CHANDRASEKARA N, SHAHIDI F. Effect of roasting on phenolic content and antioxidant activities of whole cashew nuts, kernels, and testa[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59(9):5006-5014.

[34] XU Guihua, YE Xingqian, CHEN Jianchu, et al. Effect of heat treatment on the phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of citrus peel extract[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2007, 55(2): 330-335.

[35] SINGH R S G, NEGI P S, RADHA C. Phenolic composition,antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of free and bound p henolic extracts of Moringa oleifera seed flour[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2013, 5(4): 1883-1891.

[36] DORDEVIC T M, SILER-MARINKOVIC S S, DIMITRIJEVICBRANKOVIC S I. Effect of fermentation on antioxidant properties of some cereals and pseudo cereals[J]. Food Chemistry, 2010, 119(3):957-963.

[37] OLIVEIRA M S, CIPOLATTI E P, FURLONG E B, et al. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity in fermented rice (Oryza sativa)bran[J]. Food Science and Technology, 2012, 32(3): 531-537.

[38] GODOYC ☒ V O, L☒PEZ-VALENZUELAA J A, DELGADOVARGASA F, et al. Nutraceutical beverage from a high antioxidant activity mixture of extruded whole maize and chickpea flours[J]. European International Journal of Science and Technology, 2012, 1(3): 1-14.

[39] TAO Bingbing, YE Fayin, LI Hang, et al. Phenolic profile and in vitro antioxidant capacity of insoluble dietary fiber powders from citrus (Citrus junos Sieb. ex Tanaka) pomace as affected by ultrafine grinding[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2014, 62(29):7166-7173.

A Review of Studies on Free and Bound Polyphenols in Foods

YAN Caizhi1, YE Fayin1, ZHAO Guohua1,2,*

(1. College of Food Science, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, China;2. Chongqing Special Food Programme and Technology Research Center, Chongqing 400715, China)

In recent years, plant polyphenols have become a hotspot in food science and nutrition because of the universal presence and importance for food quality and biological activities. Polyphenols in foods can fall into two categories, i.e.,free and bound polyphenols. Many studies have shown that the contribution of plant polyphenols to food quality and healt h function depends not only on their categories and amounts, but also on forms existing in food matrixes. The existing forms,analytic methods, free and bound polyphenol contents in various foods (cerea ls, fruits, vegetables, edible flowers and others)and the effects of processing on the existing forms of food polyphenols are summarized. Moreover, the existing problems and future prospects of research on free and bound polyphenols in foods are elaborated.

free polyphenols; bound polyphenols; form; analysis; processing

TS201.2

A

1002-6630(2015)15-0249-06

10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201515046

2015-03-23

国家自然科学基金面上项目(31371737);重庆市特色食品工程技术研究中心能力提升项目(cstc2014pt-gc8001)

颜才植(1990—),男,硕士研究生,研究方向为食品化学。E-mail:yancaizhi1990@163.com

赵国华(1971—),男,教授,博士,研究方向为食品化学与营养。E-mail:zhaoguohua1971@163.com