两种海星对三种双壳贝类的捕食选择性和摄食率

2013-12-08齐占会毛玉泽张继红方建光

齐占会,王 珺,毛玉泽,张继红,方建光

(1. 农业部南海渔业资源开发利用重点实验室,广东省渔业生态环境重点实验室,中国水产科学研究院南海水产研究所, 广州 510300; 2. 中国水产科学研究院黄海水产研究所,青岛 266071)

两种海星对三种双壳贝类的捕食选择性和摄食率

齐占会1, 2,王 珺1,毛玉泽2,张继红2,方建光2

(1. 农业部南海渔业资源开发利用重点实验室,广东省渔业生态环境重点实验室,中国水产科学研究院南海水产研究所, 广州 510300; 2. 中国水产科学研究院黄海水产研究所,青岛 266071)

在实验室条件下,研究了多棘海盘车和海燕这两种海星对栉孔扇贝、菲律宾蛤仔和贻贝三种双壳贝类的捕食选择性和摄食率及温度的影响,测定了捕食Q10温度系数。结果显示:多棘海盘车和海燕对三种贝类均可捕食,且表现出明显的捕食选择性,选择顺序依次为菲律宾蛤仔、贻贝和栉孔扇贝。海星对菲律宾蛤仔的摄食率显著高于其他两种贝类,分别为0.50和0.37个/d;对扇贝的摄食率最低,分别为0.05和0.07个/d。海星摄食率随水温升高而呈上升的趋势,总平均摄食干重分别为0.69 和0.79 g/d。水温从4.3 ℃升高到7.8 ℃多棘海盘车和海燕捕食Q10系数分别为6.38和2.33,而水温从7.8 ℃升高至13.3 ℃时,Q10系数没有显著升高,分别为1.13和1.22。说明水温从4.3 ℃升高时,海星捕食强度显著升高,是防御海星的重点时期。根据海星对贝类捕食的选择性,可在养殖笼内放入贻贝等低值贝类来保护扇贝,缓冲海星对扇贝的捕食,并在缓冲期间对养殖笼内的海星进行清除。

海星;多棘海盘车;海燕;捕食选择性;摄食率

海星属于棘皮动物,海星纲(Asteroidea),是典型的掠食性动物,可捕食贝类、海胆、珊瑚和螃蟹等,对潮间带生物和底栖生物群落的异质性和生物多样性具有重要影响[1- 4]。我国沿海分布的海星主要属于海盘车科(Asteriidae)和海燕科(Asterinidae)的种类。海星爆发时数量可达150000—720000个/公顷[5- 6],是养殖贝类主要敌害生物之一[7- 11]。2007年青岛附近海域海星出现暴发性增殖,几乎使沿岸海域养殖的贝类损失殆尽。作者对青岛流清河海域吊养的栉孔扇贝养殖笼内海星的情况进行了调查统计,发现几乎所有笼内都有海星存在,扇贝死亡率在80%以上。

弄清海星的摄食率、捕食选择性及关键受控因素是揭示其对海洋生物群落影响和作用机制的基础[12- 15],也是研究其防治策略,规避其危害的前提[16- 18]。但目前国内对海星捕食选择性、捕食速率及影响因素等的研究还较少[19, 33]。

多棘海盘车Asteriasamurensis和海燕Asterinapectinifera是我国沿海两种最常见的海星种类。本文以这两种海星为对象,研究了它们对栉孔扇贝、菲律宾蛤仔和贻贝三种贝类的捕食选择性和摄食率以及温度的影响,探讨了海星捕食机制,旨在揭示海星捕食生理生态学特征,为进一步研究海星防控策略,减少其对养殖贝类的危害提供科学依据。

1 材料与方法

1.1 实验材料

实验用多棘海盘车(辐径114—135 mm)和海燕(辐径41—53 mm)均从山东荣成桑沟湾寻山海区用地笼网捕获。所用栉孔扇贝Chlamysfarreri、菲律宾蛤仔Ruditapesphilippinarum和贻贝Mytilusgalloprovincialis均取自桑沟湾养殖海区。

1.2 养殖条件

实验于2008年3月19日至4月5日在山东荣成寻山集团海洋生物实验室进行。海星和贝类在水泥池(长×宽×高=6.0 ×1.0 ×0.5 m,水体2400 L)内养殖。实验用海水为桑够湾海域天然海水,经过沉淀和沙滤后使用。实验期间海水水质参数用YSI6600测量,溶解氧在5.0 mg/L以上,盐度32.14-32.54,pH 7.93—8.10。每天8:00全部换水一次。采用自然光照。实验开始前海星暂养驯化一周,使其适应养殖环境和实验处理。驯化期间混合投喂实验贝类,待海星摄食稳定后开始实验。

1.3 实验设计

多棘海盘车和海燕在水泥池内的养殖密度为5只/池,每水泥池内投喂栉孔扇贝、菲律宾蛤仔和贻贝各30粒。投喂时将这三种贝类充分混合,使各种贝在水泥池底随机分布,遭遇海星捕食的条件相同。每天7:00和17:00观察记录海星对贝类的捕食情况,捡出死壳,不补充贝类。研究这两种海星对三种不同贝类的摄食率和捕食选择性。每实验处理设置三个重复。实验用贝均是达到商品规格的贝类,贝类的软体组织在65 ℃下烘干48 h后称量干重,实验贝类生物学参数见表1。

1.4 数据处理

1.4.1 摄食率

从3月19日至4月5日记录分别记录多棘海盘车和海燕所捕食的贝类种类和数量,某种贝类开始被捕食即计为计算海星对该种贝类摄食率的起始时间。摄食率(个/d;Feed intake (FI): ind/d) 的计算公式为:

FI=D/t

式中,D为海星对某种贝类的捕食数量(个),t为时间(d)。

1.4.2 捕食比例

统计3月19日—24日,3月25日—30日和3月31日—4月5日三个时间段内,多棘海盘车和海燕所捕食的贝类的种类和数量,分析各种贝类在海星猎物中所占比例及随时间的变化。捕食比例(P)的计算公式为:

P=n/N×100%

式中,n为被海星所捕食的某一贝类的数量(个),N为海星捕食的三种贝类的总数量(个)。

1.4.3 捕食温度系数

记录两种海星在4.3 ℃、7.8 ℃和13.3 ℃下的总摄食干重。总摄食干重以所捕食的三种贝类软体组织的总干重计算,连续记录5d,以平均值作为该温度下海星的捕食强度(g/d)。温度系数(Q10) 的计算公式为:

Q10=(V2/V1)10/(t2-t1)

式中,Q10表示温度每升高10 ℃时捕食强度增加的倍数;V1和V2为捕食强度;t1和t2分别为各阶段的开始和结束温度。

1.4.4 统计分析

数据以平均值±标准误(mean±S.E.)表示。采用单因子方差分析(one-way ANOVA)和Duncan多重比较对数据差异进行分析,以Plt;0.05作为差异显著标准。数据统计分析采用Statistica 6.0软件进行。

表1 实验贝类的生物学参数指标

2 实验结果

2.1 海星捕食行为观察

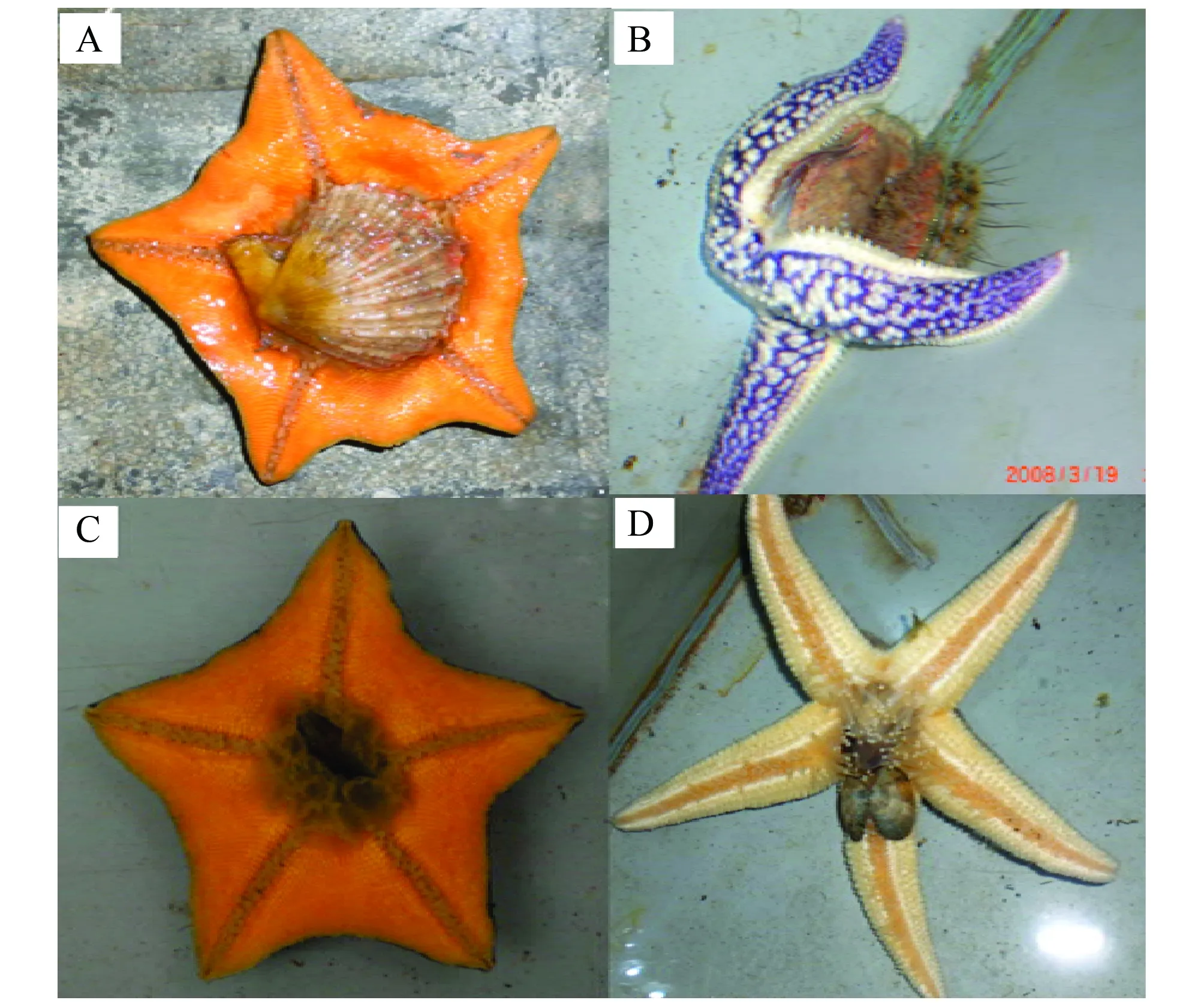

图1 海星捕食行为(A)海燕捕食栉孔扇贝,(B)多棘海盘车捕食栉孔扇贝,(C)海燕捕食贻贝,(D)多棘海盘车捕食菲律宾蛤仔Fig.1 The feeding behavior of sea stars: (A) A. amurensis prey on C. farreri, (B) A. amurensis prey on C. farreri, (C) A. amurensis prey on M. galloprovincialis, (D) A. amurensis prey on R. philippinarum

观察发现多棘海盘车和海燕捕食时主要靠腕足上细小的管足将猎物“包裹”住,抱缚于腹面盘中央的“口”部。管足吸附在贝壳上并向两侧拉伸,拉开很小的缝隙,将贲门胃伸及贝壳内注入消化液消化并吸食贝类软体组织,之后将完整的贝壳抛弃。实验过程中发现多棘海盘车和海燕可同时捕食两只或多只菲律宾蛤仔或贻贝(图 1)。相对于海燕,多棘海盘车的警惕性更高,对外界刺激也更为敏感,捕食过程中受到干扰时,很容易将已捕获的猎物“吐出”放弃捕食,而海燕可以忍受更大程度的干扰,这可能是其猎食活动更为旺盛的原因之一。实验过程中发现两种海星在白天和夜间均有捕食活动,但夜间捕食强度明显高于白天,这可能是海星对光线较暗的海底生境产生的适应性。

2.2 海星对贝类的捕食选择性

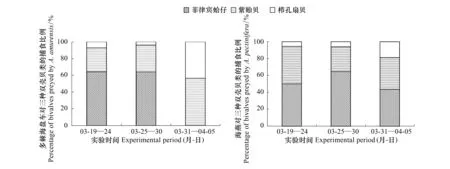

海星对贝类的选择性和捕食比例见图2。两种海星对这三种贝类均有捕食,且表现出明显的主动选择性。实验初期两种海星均明显优先捕食菲律宾蛤仔,其次为贻贝,当这两种贝类数量减少时,对栉孔扇贝的捕食比例才有所增加。3月19日—24日,多棘海盘车捕食的菲律宾蛤仔、贻贝和栉孔扇贝比例分别为64.28%,28.57%和7.14%;海燕对这三种贝类的捕食占比例分别为50%,44.44%和5.56%。结果表明多棘海盘车和海燕三种贝类的主动选择顺序依次为:菲律宾蛤仔、贻贝和栉孔扇贝。

图2 多棘海盘车(A)和海燕(B)对3种贝类的捕食比例Fig.2 The percentage of bivalves preyed by sea stars (A) Asterias amurensis and (B) Asterina pectinifera

2.3 海星对贝类的摄食率

多棘海盘车和海燕均是对菲律宾蛤仔的摄食率显著高于对其他两种贝类的摄食率,分别为0.50和0.37个/d,对扇贝的平均摄食率最低,分别为0.05和0.07个/d。对菲律宾蛤仔的摄食率显著高于其他两种贝类(Plt;0.05)(表2)。在本实验条件下,多棘海盘车和海燕摄食率均随水温升高而呈上升的趋势,每天总的平均摄食干重分别为0.69 g/d和0.79 g/d(表2,图3)。从4.3℃到7.8℃多棘海盘车和海燕的Q10系数分别为6.38和2.33,而水温从7.8℃继续升高至13.3℃时,Q10系数变化不显著,分别为1.13和1.22(表3)。

图3 海星摄食率随温度变化趋势(A)多棘海盘车和(B)海燕Fig.3 Variation of feeding rates with water temperature (A) Asterias amurensis and (B) Asterina pectinifera on bivalves

种类Species摄食率Feedingrate/(个/d)栉孔扇贝Chlamysfarreri菲律宾蛤仔Ruditapesphilippinarum贻贝Mytilusgalloprovincialis总摄食干重(g/d)Totalfeedingrate多棘海盘车Asteriasamurensis0.05±0.02a0.50±0.10b0.26±0.09c0.69±0.08海燕Asterinapectinifera0.07±0.02a0.37±0.08b0.27±0.06c0.79±0.04

同一行中没有相同字母上标的数值之间差异显著

表3 多棘海盘车和海燕的捕食温度系数

3 讨论

3.1 海星捕食选择性

海星捕食过程包括搜索遭遇猎物、捕食猎物和处理取食猎物等环节[20- 22]。每个环节如海星个体大小和处理猎物所需时间[20, 23]以及猎物的种类、大小和密度等都会影响海星对食物的选择[24, 33]。海星对食物的选择,分为主动选择和被动选择。Wong and Barbeau[16]研究了海星Asteriasvulgaris对扇贝Placopectenmagellanicus和贻贝Mytilusedulis的捕食选择性,发现在贻贝存在的情况下,无论是主动选择还是被动选择,海星都优先选择贻贝,主要是由于贻贝不能通过游泳移动来逃避捕食,更易被捕获。与之相一致,本研究也发现多棘海盘车和海燕也都表现出了对食物的主动选择性,均优先选择捕食菲律宾蛤仔和贻贝,只有这两种贝类数量变小时才增加对栉孔扇贝的捕食。这可能主要受到捕食能量效率的影响,海星捕食的能量效率主要受到猎物的丰度和能量含量高低以及搜寻和处理猎物时的能量消耗等因素的影响,这些因素是决定了海星对食物的选择[1, 25- 26]。从能量效益角度分析,单次捕食选择较大规格的贝类能量收益较高,但在捕捉和处理猎物过程中能量消耗也较多,尤其是还存在捕食不成功的风险,反而降低了捕食的能量效率。

本实验采用的栉孔扇贝个体相对较大,闭壳肌发达闭合力强,并且扇贝壳上有尖利的棘刺,不利于海星捕食,反而是选择小规格的贝类比较容易捕食,能量效率也相对更高[27- 28]。Sommer等[29]研究了个体大小对海星Asteriasrubens捕食贻贝M.edulis的影响,也发现海星倾向于捕食个体相对较大的贻贝,但不捕食壳长在4.8 cm以上的贻贝,也主要是由于能量效率的原因。杜美荣等[19]研究报道多棘海盘车优先选择贻贝,而不是菲律宾蛤仔,与本实验结果存在一定差异。这可能是由于他们所采用的贻贝(壳长10—21mm)小于菲律宾蛤仔(壳长19—27mm),而本实验采用的贻贝和菲律宾蛤仔规格相近(表 1),这也证明了贝类的个体大小是影响海星捕食选择的重要因素。

3.2 海星摄食率及温度的影响

不同种类海星的摄食率存在很大差异。Nadeau等[17]研究结果显示,在水温10—15 ℃条件下,海星A.vulgaris(辐径70—90 mm)和L.polaris(辐径90—110 mm)对扇贝P.magellanicus(壳长25—35 mm)的摄食率分别为0.9和0.02个/d,高于本实验中海星的摄食率(表2),这主要是由于海星种类和贝类规格不同,本研究采用的扇贝规格较大,能量含量较高,且对海星捕食具有一定防御抵抗能力,而小规格扇贝更易受到攻击捕食。

温度对于变温动物的生命活动具有显著的影响。研究发现海星捕食强度主要受到猎物密度和规格[17- 18]、底层基质[24]和水温[30]等的影响。温度升高会使捕食者用于捕食活动的时间增加,寻找猎物时的活动速度也更快,进而使发现猎物的机率升高,并且也会使捕捉和处理猎物的时间缩短,总体上提高了捕食效率[30]。这一现象在其它水生生物如蟹类等的捕食研究中也得到了证实[31- 32]。本研究结果显示,在一定范围内多棘海盘车和海燕对贝类的捕食强度均随着温度的升高而增加。这与Barbeau和Scheibling[30]的研究结果相一致,他们也发现海星A.vulgaris对扇贝P.magellanicus的捕食强度在一定范围内随水温上升而升高,但捕食强度升高的温度范围与本研究结果存在显著的差异。他们发现当水温从4 ℃升高至8 ℃,海星的捕食强度没有明显的变化,而温度从8 ℃继续升高至15 ℃时,捕食强度显著提高(Q10=6.9)。本研究中从4.3 ℃到7.8 ℃海星捕食强度明显提高(Q10系数分别为6.38和2.33),但继续升高至13.3 ℃,捕食强度变化不明显(Q10系数分别为1.13和1.22)(表3)。这些不同的实验结果表明不同种类海星最适捕食的温度不同。本实验是在水温4.3—13.3 ℃条件下进行的,海星在其他温度范围下的捕食情况以及捕食的最适温度还需要进一步研究确定。

3.3 海星防御建议

网笼养殖的贝类主动逃避海星捕食的能力较差,一方面由于栉孔扇贝等贝类的成熟个体通过足丝附着在养殖笼上营固着生活,另一方面具有一定游泳迁移能力种类,也几乎不可能从养殖笼内逃脱,因此只能通过采取其它措施来防御海星捕食。本研究的结果显示水温从4.3℃升高至7.8℃时海星的捕食强度显著升高,这一阶段是防御海星的重点时期。根据海星对贝类捕食的选择性,可在养殖笼内放入贻贝等低值贝类来保护扇贝,缓冲海星对扇贝的捕食,并在缓冲期间对养殖笼内的海星进行清除。

[1] Sloan N A. Aspects of the feeding biology of asteroids. Oceanography and Marine Biology Annual Review, 1980, 18: 57- 124.

[2] Power M E, Tilman D, Estes J A, Menge B A, Bond W J, Mills L S, Daily G, Castilla J C, Lubchenco J, Paine R T. Challenges in the quest for keystones. BioScience, 1996, 46: 609- 620.

[3] Witman J D, Dayton P K. Rocky subtidal communities // Bertness, M.D., Gaines, S.D., Hay, M.E. eds. Marine Community Ecology. Sinauer Associates, Massachusetts, 2001. 339 - 366.

[4] Verling E, Crook A C, Barnes D K A, Harrison S S C. Structural dynamics of a sea starMarthasteriasglacialispopulation. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2003, 83: 583- 592.

[5] Hendler G, Miller J E, Pawson D L, Kier P M. Echinoderms of Florida and the Caribbean. Washington: Smithsonian Institution press, 1995: 390.

[6] Farias N E, Meretta P E, Cledón M. Population structure and feeding ecology of the bat starAsterinastellifera(Möbius, 1859): Omnivory on subtidal rocky bottoms of temperate seas. Journal of Sea Research, 2012, 70: 14- 22.

[7] Hatcher B G, Scheibling RE, Barbeau M A, Hennigar A W, Taylor L H, Windust A. Dispersion and mortality of a population of sea scallopPlacopectenmagellanicusseeded in a tidal channel. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 1996, 53: 38- 54.

[8] Hawkes G, Day R. Review of the biology and ecology ofAsteriasamurensis:status report to Fisheries Research and Development Corporation // Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (Australia). Hobart: CSIRO Division of Fisheries,1993:38.

[9] Barbeau M. A, Hatcher B G, Scheibling R E, Hennigar A W, Taylor LH, Risk A C. Dynamics of juvenile sea scallopPlacopectenmagellanicusand their predators in bottom seeding trials in Lunenburg Bay, Nova Scotia. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 1996, 53: 2494- 2512.

[10] Cliche G, Giguère M, Vigneau S. Dispersal and mortality of sea scallops,Placopectenmagellanicus(Gmelin 1791), seeded on the sea bottom off Iles-de-la-Madeleine. Journal of Shellfish Research, 1994, 13: 565- 570.

[11] Thompson M, Drolet D, Himmelman J H. Localization of infaunal prey by the sea starLeptasteriaspolaris. Marine Biology, 2005, 146: 887- 894.

[12] Gaymer C F, Himmelman J H. Mussel beds in deeper water provide an unusual situation for competitive interactions between the sea starsLeptasteriasPolarisandAsteriasvulgaris. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2002, 277: 13- 24.

[13] Gaymer C F, Himmelman J H, Johnson L E. Distribution and feeding ecology of the seastarsLeptasteriaspolarisandAsteriasvulgarisin the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canadian Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2001, 81: 827- 843.

[14] Gaymer C F, Himmelman J H, Johnson L E. Effect of intra- and interspecific interactions on the feeding behavior of two subtidal seastars. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2002, 232: 149- 162.

[15] McClintock J B, Lawrence J M. An optimization study on the feeding behavior ofLuidiaclathrataSay (Echinodermata: Asteroidea). Marine Behavior amp; Physiology, 1981, 7: 263- 275.

[16] Wong M C, Barbeau M A. Prey selection and the functional response of sea starsAsteriasvulgarisVerrill and rock crabsCancerirroratusSay preying on juvenile sea scallopPlacopectenmagellanicusGmelin and blue musselsMytulisedulisLinnaeus. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2005, 327: 1- 21.

[17] Nadeau M, Barbeau M A, Brêthes J. Behavioural mechanisms of sea stars (AsteriasvulgarisVerrill andLeptasteriaspolarisMüller) and crabs (CancerirroratusSay andHyasaraneusLinnaeus) preying on juvenile sea scallops (Placopectenmagellanicus(Gmelin)), and procedural effects of scallop tethering. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2009, 374: 134- 143.

[18] Barbeau M A, Scheibling R E, Hatcher B G. Behavioural responses of predatory crabs and sea stars to varying density of juvenile sea scallops. Aquaculture, 1998, 169(1/2): 87- 98.

[19] Du M R, Fang J G, Zhang J H, Mao Y Z, Ge C Z, Gao Y P, Liu D H. Feeding rate and food preference ofAsteriasamurensison four species of bivalves. Fishery Modernization, 2012, 39(2): 25- 47.

[20] Himmelman J H, Dutil C, Gaymer C F. Foraging behavior and activity budgets of sea stars on a subtidal sediment bottom community. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2005, 322: 153- 165.

[21] Holling C S. The functional response of invertebrate predators to prey density. Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada, 1966, 48: 1- 86.

[22] Osenberg C W, Mittelbach G G. Effects of body size on the predator-prey interaction between pumpkinseed sun fish and gastropods. Ecological Monographs, 1989, 59: 405- 432.

[23] Arnold W S. The effects of prey size, predator size, and sediment composition on the rate of predation of the blue crab,CallinectessapidusRathbun, on the hard clam,Mercenariamercenaria. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1984, 80: 207- 219.

[24] Wong M C, Barbeau M A. Effects of substrate on interactions between juvenile sea scallops (PlacopectenmagellanicusGmelin) and predatory sea stars (AsteriasvulgarisVerrill) and rock crabs (CancerirroratusSay). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2003, 287: 155- 178.

[25] Allen P L. Feeding behaviour ofAsteriasrubens(L.) on soft bottoms bivalves: a study in selective predation. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1983, 70: 79- 90.

[26] Beddingfield S D, McClintock J B. Feeding behavior of the sea starastropectenarticulates(Echinodermata: Asteroidea): an evaluation of energy-efficient foraging in a soft-bottom predator. Marine Biology, 1993, 115: 669- 676.

[27] Juanes F, Hartwick E B. Prey size selection in dungeness crabs: the effect of claw damage. Ecology, 1990, 71: 744- 758.

[28] Gaymer C F, Dutil C, Himmelman J H. Prey selection and predatory impact of four major sea stars on a soft bottom subtidal community. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2004, 313: 353- 374.

[29] Sommer U, Meusel B, Stielau C. An experimental analysis of the importance of body-size in the seastar-mussel predator-prey relationship. Acta Oecologica, 1999, 20(2): 8l- 86.

[30] Barbeau M A, Scheibling R E. Temperature effects on predation of juvenile sea scallops (PlacopectenmagellanicusGmelin) by sea stars (AsteriasvulgarisVerrill) and crabs (CancerirroratusSay). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1994, 182: 27- 47.

[31] Nickell T D, Moore P G. The behavioural ecology of epibenthic scavenging invertebrates in the Clyde Sea area: laboratory experiments on attractions to bait in moving water, underwater TV observation in situ and general conclusions. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1992, 159: 15- 35.

[32] Yu Z H, Yang H S, Liu B Z, Xing K, Xu Q, Zhang L B. Predation of scallopChlamysfarreriby crab Charybdis japonica. Marine Sciences, 2010, 34(12):62- 66.

[33] Liu J, Zhang X M. Study on the prey selection of sea starsAsteriasamurensispreying on juvenile oysterCrassostreagigas, musselsMytilusedulisand clamsRuditapesphilippinarum. Journal of Ocean University of China, 2012, 42(7/8): 98- 105.

参考文献:

[19] 杜美荣, 方建光, 张继红, 毛玉泽, 葛长字, 高亚平, 刘顶海. 多棘海盘车对四种贝类摄食率和选择性的初步研究. 渔业现代化, 2012, 39(2): 25- 47.

[32] 于宗赫, 杨红生, 刘保忠, 邢坤, 许强, 张立斌. 日本蟳捕食栉孔扇贝机制的初步研究. 海洋科学, 2010, 34(12):62- 66.

[33] 刘佳,张秀梅. 多棘海盘车对太平洋牡蛎、紫贻贝、菲律宾蛤仔摄食选择性的研究.中国海洋大学学报, 2012, 42(7/8): 98- 105.

PreyselectionandfeedingrateofseastarsAsteriasamurensisandAsterinapectiniferaonthreebivalves

QI Zhanhui1, 2, WANG Jun1, MAO Yuze2, ZHANG Jihong2, FANG Jianguang2,*

1KeyLaboratoryofSouthChinaSeaFisheryResourcesDevelopmentandUtilization,MinistryofAgriculture;KeyLaboratoryofMarineFisheryEcologyEnvironmentofGuangdongProvince/SouthChinaSeaFisheriesResearchInstitute,ChineseAcademyofFisherySciences;Guangzhou510300,China2YellowSeaFisheriesResearchInstitute,ChineseAcademyofFisheriesSciences,Qingdao266071,China

Sea stars are one of the primary predators of shellfish and often cause mass mortality among cultured shellfish. To develop effective control strategies, it is critical to understand the feeding ecophysiology (e.g., feeding rate and prey selection) of sea stars.

AsteriasamurensisandAsterinapectiniferaare the dominant sea star species in the coastal waters of China. We evaluated prey selection and the feeding rate of these two sea stars on three species of bivalves: scallopsChlamysfarreri, clamsRuditapesphilippinarum, and blue musselsMytilusgalloprovincialis. The experimental sea stars and bivalves were collected from Sanggou Bay, Northern China and transported to our seaside laboratory. The animals were acclimated to laboratory conditions for 7 d prior to the initiation of the experiment. The experiment was conducted between March 19 and April 5, 2008, at different seawater temperatures. Following acclimation, the sea stars were placed in cement tanks (L×W×H=6×1×0.5 m) at a density of 5 individuals per tank (single species per tank). The sea water was pumped from Sanggou Bay and sand filtered. Daily water exchange was ca 100%. We placed the bivalves (N=30 per species) evenly in each tank to ensure the sea stars had an equal probability of encountering the three species of bivalves. Each treatment was conducted in triplicate (N= 3 tanks). The number of bivalves of each species preyed upon by the sea stars was recorded twice daily at 7:00 and 17:00. In addition, we measured theQ10coefficient at water temperatures ranging from 4.3—7.8℃ and from 7.8—13.3℃.

Both species of sea star preyed on all three bivalve species. Similarly, both species exhibited preference in the order clamgt;musselgt;scallop. During the first part of the experiment (March 19—24),A.amurensispreyed on 64.28, 28.57, and 7.14% of the scallops, clams, and blue mussels, respectively.A.pectiniferapreyed upon 50, 44.44, and 5.56% of the bivalve species, respectively. The mean feeding rates ofA.amurensisandA.pectiniferaon the clam (0.50 and 0.37 ind/d, respectively) and blue mussel (0.26 and 0.27 ind/d, respectively) were significantly higher than those on the scallop (0.05 and 0.07 ind/d, respectively). The feeding rate was significantly influenced by water temperature and generally increased with increasing water temperature. The total mean feeding rates of the two sea stars were 0.69 and 0.79 g·d-1, respectively (based on dry tissue weight of bivalves). As water temperature increased from 4.3 to 7.8℃, theQ10coefficients forA.amurensisandA.pectiniferawere 6.38 and 2.33, respectively. However, when the water temperature was increased from 7.8 to 13.3℃, there was no increase in the feeding rate (Q10=1.13 and 1.22, respectively). Our results have implications for the provision of protective refuges for the species of interest (i.e., scallops) during culture in suspended lantern nets. Protective strategies are most likely to be needed when the water temperature increases above 4.3℃, as the feeding rate and activity of sea stars increased significantly above this point. Based on prey selectivity, bivalves that have a lower commercial value (e.g., blue mussels) may be co-cultured in the scallop lantern nets to serve as a buffer against predators. Furthermore, any sea stars present in the cultivation nets should be removed during the buffering period.

sea star;Asteriasamurensis;Asterinapectinifera; prey selection;feeding rate

国家自然科学基金(41106088);“十二五”国家科技支撑计划(2011BAD13B02);863计划(2012AA052103);重点实验室开放课题(201104,MESE- 2011- 02,开- c10- 09)

2012- 08- 21;

2013- 08- 20

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: Fangjg@ysfri.ac.cn;qizhanhui@scsfri.ac.cn

10.5846/stxb201208211174

齐占会,王珺,毛玉泽,张继红,方建光.两种海星对三种双壳贝类的捕食选择性和摄食率.生态学报,2013,33(16):4878- 4884.

Qi Z H, Wang J, Mao Y Z, Zhang J H, Fang J G.Prey selection and feeding rate of sea starsAsteriasamurensisandAsterinapectiniferaon three bivalves.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2013,33(16):4878- 4884.