当代芬兰建筑中的自然和现代主义

2012-07-27尤哈那拉赫蒂JuhanaLahti

尤哈那·拉赫蒂/Juhana Lahti

孙凌波 译/Translated by SUN Lingbo

1 阿尔瓦·阿尔托,帕伊米奥疗养院/Alvar Aalto, Paimio Sanatorium

2 埃里克·布吕格曼,卡伊诺住宅/Erik Bryggman,Villa Kaino

芬兰建筑主要因两点而闻名:实用而直接的现代主义和一种同自然之间的虚构的关系。从阿尔瓦·阿尔托和他同时代——包括埃里克·布吕格曼(Erik Bryggman)和保利·布卢姆斯泰特(Pauli E.Blomstedt)在内——的那些设计了80年前的芬兰现代建筑作品的建筑师开始,就是如此。阿尔托在1930年代的设计,特别是完成于1933年的帕伊米奥疗养院,布吕格曼设计的私人住宅和图尔库的公寓区,以及布卢姆斯泰特的教堂设计,都是芬兰现代建筑早期阶段的标志。

在这之后,现代主义运动的主流和分支总是成为芬兰建筑学习的对象。如此忠诚于现代主义的原因,可以归结到芬兰自1917年独立以来的社会发展,以及北欧人一贯的建筑和设计方向。

北部的地理位置和文化

在北欧的多种现代主义中,建筑是与众多北部欧洲的文化特性交织在一起的。起决定性的因素是气候和自然环境,同时还有从路德教而来、体现在北欧福利国家的一种共有的精神。这里值得一提的是,在当地民众与自然之间的关系形成的过程中,有一个关键因素——“自由信步”的理念,简而言之,即在一定限度内,每个人都有权利进入到自然环境及其所赋予的一切中去。这一传统在那些居住环境与自然紧密相联的地方广为人知,在北欧国家更是根深蒂固。

波罗的海地区的自然环境十分富足、多样,且尺度较小。内陆中不计其数的湖面形成了广阔的水路。芬兰被称为“千岛之国”。实际上可以说,芬兰的自然环境充满了各种独特的场所。我们没有一望无际的海岸沙滩或巨大的高差,但是,我们拥有河、湖和群岛。多样且无所不在的水陆交替,为芬兰的自然环境提供了一种韵律。这种韵律既是视觉上的,也是精神上的。此外,四季的变换——温暖明亮的夏季和寒冷多雪的冬季——强化了景观的多变,对自然空间的应用有着显著影响。

关于芬兰建筑

前文所述都与芬兰人所认知的好建筑密切相关。在这里,成为好建筑的关键因素是同地段或场所的联系,及其空间体验。

首先,成为好建筑要尊重地段及其历史,无论它是在自然环境里还是在城市之中。以阿尔瓦·阿尔托为代表的1930-1960年代的芬兰建筑师,一贯坚持在项目进程中对地段上的树木加以保护。这是让自然成为建筑院落一部分的方式之一。在这个时代,区域划分成为城市规划的一部分。在郊区规划中,居住区同自然绿色区域的联系尤为重要。对历史建筑遗产的评估是近年城市规划中的一种现象。历史性木构建筑作为现代化发展中被忽视的一面,在1970年代的芬兰城市中被大量摧毁。破坏的疯狂在那之后平息下来,但事情还未完全改变。数年过去之后,现代建筑也已经成为我们建筑遗产的一部分。同样,历史性的城市环境现在也被认为是值得保留的。在芬兰,并不存在像芬兰南部邻国爱沙尼亚首都塔林所出现的那种历史建筑竖向扩建的案例。类似的一个启示性案例就是关于收录在本期专辑中的ALA建筑师事务所的“云城市”设计的论战。

第二,它把建筑紧邻的环境视为建筑的延伸和整体建筑设计的一部分。进入一栋建筑的路径和从室内看到的室外景观,是建筑及其体验的一个特别重要的部分。让自然光线进入建筑是现代建筑中的一个普遍理念,在我们这个冬季只有极短时间宝贵日照的北纬度地区尤为受欢迎。上面提到过的对一个地段或场所的特别强调,与建筑的特色紧密相关。对于建筑周围景观视野的细致考量,则会将建筑设计与地段和周围自然环境联系在一起。完成于1957年、由海基·西伦(Heikki Siren)和凯亚·西伦(Kaija Siren)设计的Otaniemi礼拜堂是一个著名的案例。接近和离开一栋建筑的方式在创造空间体验的过程中扮演着重要角色。与此相关的案例是亚梵拓建筑师事务所设计的圣劳伦斯礼拜堂。该礼拜堂处在一个历史性的环境之中,设计的精华在于接近建筑、进入建筑和离开它进入教堂庭院的一系列运动。

第三,它包含低密度居住的理想,这与芬兰人口极为稀少的现实有关。在这方面,芬兰在城市规划中的建筑文化,同一些国际大都市或人口稠密区域差别很大。这种理想在今天日渐稠密的城市环境中如何实现是具有争议的,但是,芬兰人仍把自然环境视为他们城市的一部分,并对高层建筑持有怀疑态度。对于自然环境的偏爱在1950年代建于赫尔辛基区域的“森林郊区”项目中有所体现。其中一个在塔皮奥拉,依据地形曲线布局的低层公寓街区坐落在树林中,地块间也没有围墙分隔。高层建筑目前是赫尔辛基区域的一个活跃的讨论话题,“云城市”项目就是这样的案例之一。反对高层建筑的论据,包括对历史性城市空间的保护和自然光线的重要性这两方面。人们不希望高层建筑超越、破坏目前的天际线,并对城市的其他部分产生遮挡,特别是在太阳几乎很少升到地平线以上的冬天。

公共建筑的重要性

包括公共医疗、公共图书馆、教育体系和国有教堂在内的各种各样的公共建筑,与福利国家服务有着重要关联。

大部分芬兰人都是路德教教徒。在基督教的路德教会传统中,教堂建筑少有装饰,多用于安静的礼拜仪式。礼拜堂是为葬礼仪式而设计的更小型的建筑。最新的宗教建筑强调了集体性及传统的建造方式并把自然作为一种视觉元素。

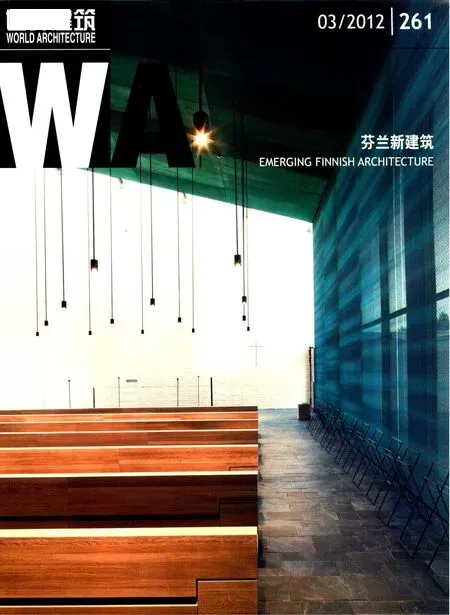

亚梵拓建筑师事务所设计的圣劳伦斯礼拜堂是将现代建筑传统升级而满足当代需求的一个范例。雅致而独特的材料选择和采光方案,使这个建筑艺术作品近乎完美,同时,令其在现代芬兰礼拜堂建筑的链条中占据了一席之地。在此之前著名的礼拜堂建筑还包括位于土尔库、在同一块墓地园区中相对而立的由埃里克·布吕格曼设计的复活礼拜堂(1941)和佩卡·皮特凯宁(Pekka Pitkänen)设计的神圣十字礼拜堂(1967)。

现代建筑传统也体现在萨纳克森纳胡(Sanaksenaho)建筑师事务所设计的位于希文萨洛的圣亨利基督教会艺术礼拜堂(2005)和郎安溪-海希莱(Lassila Hirvilammi)建筑师事务所在于韦斯屈莱设计的库奥卡拉教堂。这些项目的室内方案会令人联想到埃罗·埃里凯宁(Eero Eerikäinen)和奥斯莫·西帕里(Osmo Sipari)设计的萨拉教堂(1950)和维尔约·雷维尔(Viljo Revell)设计的位于康阿斯阿拉的Vatiala礼拜堂(1960)。

学校和托儿所是社区建筑的另一类案例。目前的芬兰教育体系是全世界最优秀的体系之一,这可能是芬兰作为福利国家的最大成就。每个人从托儿所开始都有同等的教育机会。教育体系也为保持芬兰的文化凝聚力做出了贡献。对于舒适的教学设施的设计传统由来已久。学校的体育场一直被作为整体设计的一部分加以考虑,这对于托儿所来说尤为重要,因为户外游戏是儿童日常生活的一个重要部分。安全的体育场地由此应该成为儿童建筑的一个组成部分。位于紧邻赫尔辛基的埃斯坡的两栋建筑——维斯塔斯建筑师事务所设计的克蔻加尔维综合学校(2010)和JKMM建筑师事务所设计的萨乌娜拉赫蒂儿童之家(2011),是这类建筑中的典范。

适度居住的理念

一个民主社会的悠久传统体现在住宅的形式和理想上。让每个人都拥有高品质的住宅,已经成为北欧福利国家意识形态的核心。与此相关的案例是低租金的小型学生公寓。通常,一些最优秀的建筑师会通过建筑竞赛获得委托设计学生住宅。这样的案例包括受到1950年代北欧居住建筑启发的由Playa建筑师事务所设计的位于维基的HOAS学生公寓(2010),以及布鲁诺&毛努拉(Brunow & Maunula)事务所设计的位于Kumpula、作为喧嚣城市中宁静一隅的HOAS学生公寓(2007)。

从另一个角度来看,民主传统和迄今为止的人与其环境的自然关系,都同大多数芬兰人所熟悉的夏季住宅的传统有关。这一传统也与我们的自然景观密切相关——正如上文提到的,我们的自然景观中包含着无以计数的场所。夏季住宅案例中值得一提的是那些在公共娱乐区域的租赁地块上、对所有人开放的夏季别墅,它们最初是为穷困民众设计的。这是“信步自由”理念的一种有趣的延伸,仅在赫尔辛基一地,就有数千个这样的夏季别墅。在21世纪之初,这一传统通过新一代城市居民的发掘而重获新生。维斯塔斯建筑师事务所设计的位于Lauttasaari的“城市别墅”,实现了对传统概念的一次完美的更新。夏季别墅广受欢迎,人们还为此规划了新的服务区域。比如,夏季别墅区就被包括在了赫尔辛基东部的新居住区——Kruunuvuorenranta的规划之中。

本期专辑中所展现的很多项目都体现了上文提到的特点。它们大多通过建筑设计竞赛而实现。在芬兰,建筑设计竞赛的传统可以追溯到19世纪晚期。竞赛是找到最佳可能方案的一种有效的方式,这也是我们民主文化的一种体现——每个人都有机会展现他们的才能。在本文中,我对专辑中的某些项目进行了较为详尽的说明。在关系到住宅形式和公共空间设计的项目中,传统与激动人心的当代方案相结合而形成了芬兰建筑的特色。而所有的项目都或多或少地带着骄傲与尊敬,展现了对于北欧现代建筑传统的认知。□

Finnish architecture is renowned primarily for two things: pragmatic and no-nonsense modernism and a mythical relationship with nature. This has been the case ever since Alvar Aalto and his contemporaries, including Erik Bryggman and Pauli E. Blomstedt, designed the first masterpieces of Finnish modern architecture some 80 years ago. Aalto's 1930s designs, especially the Paimio Sanatorium completed in 1933, Bryggman's private houses and blocks of flats in the city of Turku, and Blomstedt's church designs, most importantly the Kannonkoski Church completed in 1938, mark the early stage of Finnish modern architecture.

Modernism has subsequently been the movement that the mainstream, and often also the alternative, Finnish architecture has leant on. The commitment to modernism is related to Finland's social development since it gained independence in 1917 and the Nordic approach to architecture and design.

Northern Location and Culture

In the Nordic variety of modernism, the architecture is interwoven with many Northern European cultural traits. The determining factors at play are climate and natural surroundings, but also a communal spirit, drawing on Lutheranism, which has been embodied by the Nordic welfare state. A key characteristic in the formation of the local people's relationship with nature, which is worth mentioning here, is the idea of "freedom to roam", which, in a nutshell, means that everyone has the right to access the natural environment and what it offers,within certain limits. This tradition, which is known globally by people who live in close connection with nature, has stood its ground in the Nordic countries.

The natural environment in the Baltic Sea region is very rich, varied and small in scale. The inland, again, features an endless number of lakes that form vast waterways. Finland is known as the land of a thousand lakes. In fact, you can say that Finnish nature is filled with unique places. We do not have endless sandy beaches by oceans or particularly great differences in height. Instead, we have rivers, lakes and archipelagos. This varied and omnipresent alternation of land and water provides a rhythm to the Finnish natural landscape. This rhythm is both visual and spatial. In addition, the changing of the four seasons, with warm and light summers and dark, snowy and cold winters when the waterways freeze, accentuates the variability of the landscape and has a considerable effect on the use of natural space.

On Finnish Architecture

I see that all the above is closely associated with what people perceive as good architecture in Finland. Being tied to a site or place and spatial experience are key issues here.

Firstly, what is considered good architecture is linked with having respect for a site and its history, whether in a natural or an urban setting.The leading Finnish architects from the 1930s to the 1960s, most importantly Alvar Aalto, consistently insisted that the trees on building sites were to be protected against damage throughout the projects.This was a way to allow nature to be a concrete part of the buildings’ yard areas. During this era,zone thinking became part of urban planning, and the link between residential areas and natural green zones assumed particular prominence in suburban planning. In urban planning, having an appreciation for historic building stock is a phenomenon of recent decades. As a flip side to the development of modernisation, the 1970s still saw numerous

3 保利·布卢姆斯泰特,Kannonkoski 教堂/Pauli E. Blomstedt,Kannonkoski Church

4 海基和凯亚·西伦,Otaniemi礼拜堂/Kaija and Heikki Sirén,Otaniemi Chapel

historic wooden buildings pulled down in practically all Finnish cities. The demolition frenzy has since subsided, although things have not changed completely. Over the decades, modern architecture,too, has been accepted as part of our built heritage.Similarly, historic urban environments are now considered worth preserving. In Finland, there are no cases of vertical expansion of historic buildings,as, for example, in Tallinn, the capital of Estonia,Finland's southern neighbour. A revealing example of the situation is the controversy over the Cloud City design by ALA Architects, which is presented in this magazine.

Secondly, it is linked with viewing a building's immediate surroundings as its expansion and an integral part of the overall architectural design. The entry into a building and the views from inside are a particularly important part of the architecture and the way it is experienced. Allowing natural light into a building, an idea prevalent in modern architecture, was enthusiastically welcomed at our northern latitudes, where there are precious few hours of sunlight in the wintertime. Placing special emphasis on a site or place, which I mentioned above, is closely related to architectural character.The carefully thought-out views that open onto the building's surroundings tie it to the site and the surrounding nature to the architectural design. A well-known example of this is the Otaniemi Chapel by Heikki Siren and Kaija Siren, completed in 1957.The approach to and exit from a building play an important role in creating a spatial experience. A case in point is the Chapel of St. Lawrence designed by Avanto Architects. Located in a historical setting,the essence of the chapel design is the movement towards the building, into it and back out of it into the churchyard.

Thirdly, it includes the ideal of low-density living, which is related to the fact that Finland is a very sparsely populated country. In this respect, the Finnish architectural culture in urban planning differs considerably from the situation in international metropolises or other densely populated areas. How this ideal is realised in today's increasingly dense urban environment is arguable,but Finns still value natural environments as part of their cities and remain sceptical about high-rise buildings. The appreciation of natural environments shows, for example, in the“forest suburbs” built in the 1950s in the Helsinki region. One of these is Tapiola, in which fairly low blocks of flats sit amidst trees, laid out according to the contours of the terrain and without fences separating the plots.High-rise construction is presently a topic of lively discussion in the Helsinki region, and the Cloud City project is one example of this. The arguments

5 里克·布吕格曼,复活礼拜堂/Erik Bryggman,Resurrection Chapel

6 佩卡·皮特凯宁,神圣十字礼拜堂/Pekka Pitkänen,Chapel of Holy Cross

against high-rises include the preservation of historic urban spaces and the importance of natural light: people do not want tall buildings to rise above the current skyline for fear of changing the cityscape and overshadowing the rest of the city,especially in the winter, when the sun barely rises above the horizon.

The Signifi cance of Public Buildings

Various public buildings are importantly linked to the welfare state services, which encompass public health care, public libraries, the education system and the state church.

Most Finns are members of the Lutheran church. In the Lutheran tradition of Christianity,church buildings feature little ornamentation and they are mostly used for silent worship. Chapels are smaller buildings that are designed for funeral ceremonies. The more recent religious buildings highlight communality, nature as a visual element,and traditional building methods.

The Chapel of St. Lawrence by Avanto Architects is a fine example of how the heritage of modern architecture has been updated to meet contemporary needs. The elegant and unique material choices and lighting solutions perfect this architectural work of art, which at the same time takes its place in the chain of modern Finnish chapel buildings, including the Resurrection Chapel by Erik Bryggman (1941) and the Chapel of the Holy Cross by Pekka Pitkänen (1967), which form a pair on the same cemetery site in the city of Turku.

The heritage of modern architecture is also shown in the St. Henry's Ecumenical Art Chapel in Hirvensalo by Sanaksenaho Architects (2005) and the Kuokkala Church in Jyväskylä by Lassila Hirvilammi Architects (2009). The interior solutions of these projects demonstrate the architects' familiarity with the designs of the Salla Church by Eero Eerikäinen and Osmo Sipari (1950) and the Vatiala Chapel in Kangasala by Viljo Revell (1960).

Schools and nurseries are another example of architecture designed for communities. The current Finnish education system is among the best in the world and is perhaps the greatest achievement of the Finnish welfare state. Everyone is given equal opportunities in education, starting from the nursery. The education system also plays a role in maintaining cultural cohesion in Finland. The design of comfortable facilities that support teaching has a strong tradition. School playgrounds are considered to be part of the overall design, which is especially important with nurseries, as playing games outside is a significant part of the children's day. Safe playgrounds should therefore be an integral part of buildings for children. Fine examples of designs in this category are the Kirkkojärvi School by Verstas Architects (2010) and the Saunalahti Children's House by JKMM Architects (2011), both located in Helsinki's neighbouring city of Espoo.

The Ideal of Modest Living

Having a long-lasting tradition of a democratic society shows in housing forms and ideals. Making high-quality housing available for everyone has been at the core of the Nordic welfare state ideology.A case in point is the small and low-rent student flats. Often, some of the best architects are hired for the design of student housing, and projects are subject to architectural competition. This was the case with the HOAS student housing unit in Viikki by Playa architects (2010), which was inspired by the 1950s Nordic residential architecture, and the HOAS student housing unit at Intiankatu 20 in Kumpula by Brunow & Maunula (2007), which is designed to function as a quiet pocket in a noisy urban setting.

From another angle, the democratic tradition and the, as yet, natural relationship between people and their environment is linked to the tradition of summer residences, with which most Finns are familiar. The tradition is also closely related to our natural landscape, which, as I mentioned above,is seen to contain countless places. A noteworthy example of summer residences designed to be available to all are the summer cottages that are located on rented plots in public recreation areas and that were originally designed for the underprivileged. This is an interesting extension to the right of freedom to roam, and there are thousands of summer cottages like these in Helsinki alone. At the start of the 21st century, this tradition is enjoying a revival, as new generations of city

7 埃罗·埃里凯宁和奥斯莫·西帕里,萨拉教堂/Eero Eerikäinen and Osmo Sipari,Salla Church

8 维尔约·雷维尔,Vatiala礼拜堂/Viljo Revell. Vatiala Chapel

9 阿尔奈·艾尔维,维尔约·雷维尔等,塔皮奥拉东部郊区/Aarne Ervi Viljo Revell et al,Tapiola Eastern Suburb(1-9 由芬兰建筑博物馆提供/Photos from MFA)

residents have discovered it. The City Cottage in Lauttasaari by Verstas Architects (2010) is a superb update of the traditional concept. The summer cottages are sought after and new areas to accommodate them are being planned. As an example, summer cottage areas are included in the plan of Kruunuvuorenranta, a forthcoming new residential area in eastern Helsinki.

Many of the projects presented in this magazine reflect the characteristics mentioned above. A large number of them have been realised as a result of architectural competitions. The practice of architectural competitions has a long tradition that goes back to the late 19th century.Competitions are an effective way of finding the best possible solution but they also serve as a manifestation of our democratic culture, as everyone gets an opportunity to showcase their skills. In this article, I have highlighted specific projects to illustrate in more detail the issues discussed. The projects relate to the forms of housing and the design of communal spaces,in which traditions and exciting contemporary solutions meet in a way that is characteristic of Finnish architecture. Moreover, they all, to a greater or lesser extent, exhibit an awareness of the tradition of Nordic modern architecture, and they do so with pride and respect. □