One hundred and seventy-eight consecutive pancreatoduodenectomies without mortality: role of the multidisciplinary approach

2011-07-05JaswinderSamraRaulAlvaradoBachmannJulianChoiAnthonyGillMichaelNealeVikramPuttaswamyCameronBellIanNortonSarahChoStevenBlomeRitchieMaherSivakumarGananadhaandThomasHugh

Jaswinder S Samra, Raul Alvarado Bachmann, Julian Choi, Anthony Gill, Michael Neale, Vikram Puttaswamy, Cameron Bell, Ian Norton, Sarah Cho, Steven Blome, Ritchie Maher, Sivakumar Gananadha and Thomas J Hugh

Sydney, Australia

Original Article / Pancreas

One hundred and seventy-eight consecutive pancreatoduodenectomies without mortality: role of the multidisciplinary approach

Jaswinder S Samra, Raul Alvarado Bachmann, Julian Choi, Anthony Gill, Michael Neale, Vikram Puttaswamy, Cameron Bell, Ian Norton, Sarah Cho, Steven Blome, Ritchie Maher, Sivakumar Gananadha and Thomas J Hugh

Sydney, Australia

BACKGROUND:Pancreatoduodenectomy offers the only chance of cure for patients with periampullary cancers. This, however, is a major undertaking in most patients and is associated with a significant morbidity and mortality. A multidisciplinary approach to the workup and follow-up of patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy was initiated at our institution to improve the diagnosis, resection rate, mortality and morbidity. We undertook the study to assess the effect of this approach on diagnosis, resection rates and short-term outcomes such as morbidity and mortality.

METHODS:A prospective database of patients presenting with periampullary cancers to a single surgeon between April 2004 and April 2010 was reviewed. All cases were discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting comprising surgeons, gastroenterologists, radiologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists and nursing staff. A standardized investigation and management algorithm was followed. Complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification.

RESULTS:A total of 295 patients with a periampullary lesion were discussed and 178 underwent pancreatoduodenectomy (resection rate 60%). Sixty-one patients (34%) required either a vascular or an additional organ resection. Eighty-nine patients experienced complications, of which the commonest was blood transfusion (12%). Thirty-four patients (19%) had major complications, i.e. grade 3 or above. There was no in-hospital, 30-day or 60-day mortality.

CONCLUSIONS:Pancreatoduodenectomy can safely be performed in high-volume centers with very low mortality. The surgeon's role should be careful patient selection, intensive preoperative investigations, use of a team approach, and an unbiased discussion at a multidisciplinary meeting to optimize the outcome in these patients.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 415-421)

pancreatoduodenectomy; multidisciplinary; vascular resection

Introduction

Partial pancreatoduodenectomy is a complex procedure involving resection of the pancreatic head, the duodenum, the common bile duct and the gallbladder. The operation was originally described by Kausch[1]and popularized by Whipple et al.[2]It offers the only possibility of cure for periampullary cancers.[3]However, for the majority of patients with a periampullary cancer, resection is not an option, as they have metastatic disease at initial presentation. Others are deemed unfit for surgery because of poor cardio-respiratory status or associated co-morbidities. A small number of patients often refuse surgery because of their psycho-social perceptions of their disease or for other reasons.

In order to achieve an optimal outcome in these patients, a logical work-up is essential. More importantly, patients need to be assessed by a multidisciplinary team. The work-up includes imaging to assess the extent of tumor as well as the patient's ability to tolerate surgery. A modern multiphase CT can accurately detect liver metastasis and vascular encasement. Laparoscopy, when combined with modern imaging, has been instrumental in reducing the rate of negative laparotomy for advanced disease. In the past, many surgeonsviewed the abutment of the portal vein by tumor as a contraindication to curative surgery. In the last 15 years, it has been demonstrated that partial portal vein resection can be performed safely.[4]The outcome of these patients is similar to those without portal vein involvement provided a negative tumor margin is achieved.[5]This has become a standard operation in major pancreatic units. Selection bias by the surgeon can have a significant impact on his or her operative mortality. The indications for not proceeding with operative intervention should be documented when assessing the resection rate or operative mortality. The mortality associated with pancreatoduodenectomy has decreased from 25% in the 1970s[6]to less than 5% in the last decade.[7]However, the morbidity has remained at 40%.[8]In the past, morbidity was difficult to assess as there were no strict definitions of complications. This task has been simplified by the development of standardized definitions of pancreatic fistula,[9]delayed gastric emptying[10]and hemorrhage.[10]The assessment of complications has also been further refined, an example of which is the Clavien-Dindo classification.[11]This classification is treatment-driven and is based on measures taken to deal with a given complication.

In our institution, a multidisciplinary approach was adopted for the management of all periampullary tumors in 2004. This study aimed to document the impact of this approach on patients presenting with periampullary cancer in relation to diagnosis, resection rate, mortality and short-term outcomes (blood transfusion and morbidity).

Methods

A computerized record of 295 patients who were referred with a periampullary tumor to a single surgeon (Samra JS) between April 2004 and April 2010 has been maintained prospectively on the Northern campus of the University of Sydney. All cases were discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting, which was attended by surgeons, radiologists, gastroenterologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists and nursing staff. Based on the clinical presentation, blood tests (liver function tests, CA19-9, chromogranin A, IgG4) and the radiological findings, recommendations were made. The members of the team took part in the assessment of these patients for surgery and recommendations were made where further investigations were required. A number of patients required a more detailed multidetector computer tomography (MDCT) compared with the original CT scan because of poor-quality images. Members of the team were instrumental in the critical analysis of preoperative images and recommendation for investigations. Pre-operative identification of possible vascular and adjacent organs was increased by the involvement of the team. All patients with metastasis, encasement of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) or complete occlusion of the portal vein (PV) or superior mesenteric vein (SMV) over a length >4 cm were considered unresectable. Those with either tumor abutment of the SMA, short distance (1 cm) encasement of the common hepatic artery or PV/SMV junction involvement were categorized as borderline resectable, as a modification of the MD Anderson resectability criteria.[12]Patients in this group were offered resection on a selective basis. When there was disagreement between the members of the team, then a second opinion was sought from an independent institution and this occurred in a number of cases.

All patients with angina, uncontrolled hypertension, atrial fibrillation, diabetes or a previous history of cardiac surgery were investigated by electrocardiogram, echocardiogram and a full clinical assessment by a cardiologist. Patients with an ejection fraction of less than 30% were selectively advised against surgery and all those with a significant history of smoking had a respiratory assessment including an FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 second), a VC (vital capacity) and a six-minute walk test.

Patients with a serum CA19-9 less than 300 IU/L underwent a single-stage procedure, which included a laparoscopy followed by a pancreatoduodenectomy. Those with a serum level of CA19-9 greater than 300 IU/L had a laparoscopy one week prior to their pancreatoduodenectomy. An en-bloc resection technique was used as described previously.[13]The hospital stay was calculated from the day of surgery until the day of discharge. Complication data were collected prospectively using the Clavien-Dindo classification system. Inhospital mortality, along with the 30-day and 60-day mortality rates, was also documented. Statistical analysis was carried out using the Mann-Whitney U test for comparing different groups.

Results

Fig. The outcomes of 295 patients with a possible operable lesion in the head of the pancreas.

The management pathway of the original cohort of 295 patients who presented with a resectable periampullary lesion is demonstrated by a flow chart (Fig.). A dedicated fine cut MDCT detected additional liver lesions in 36 (36/295, 12.2%) patients as confirmed by fine needle aspiration biopsy. In a further cohort of 26 patients, the refined imaging along with multi-planar reconstructions and maximal intensity projections were able to demonstrate either SMA encasement, celiac artery encasement or complete occlusion of the PV. Twenty-three patients were excluded on fitness grounds; 10 of these had senile dementia and the remainder had severe cardio-respiratory disease. Five patients with resectable disease declined surgical intervention. As a result of the preoperative investigations and the discussion at the multidisciplinary meeting, 205 of the 295 patients (69.5%) were found to be suitable to undergo laparoscopy. Of these 205 patients, 16 were found to have peritoneal or liver lesions on laparoscopy and these were all confirmed as metastatic disease by frozen section. Laparotomy was done in the remaining 189 patients (189/295, 64%). In this group, resection was abandoned in eleven; four of these had subtle subcapsular liver lesions not identified during laparoscopy and seven had more extensive tumor around the SMA. The resection rate was therefore 86.8%, i.e. 178 of 205 patients were found suitable for resection following discussions at the multidisciplinary meeting.

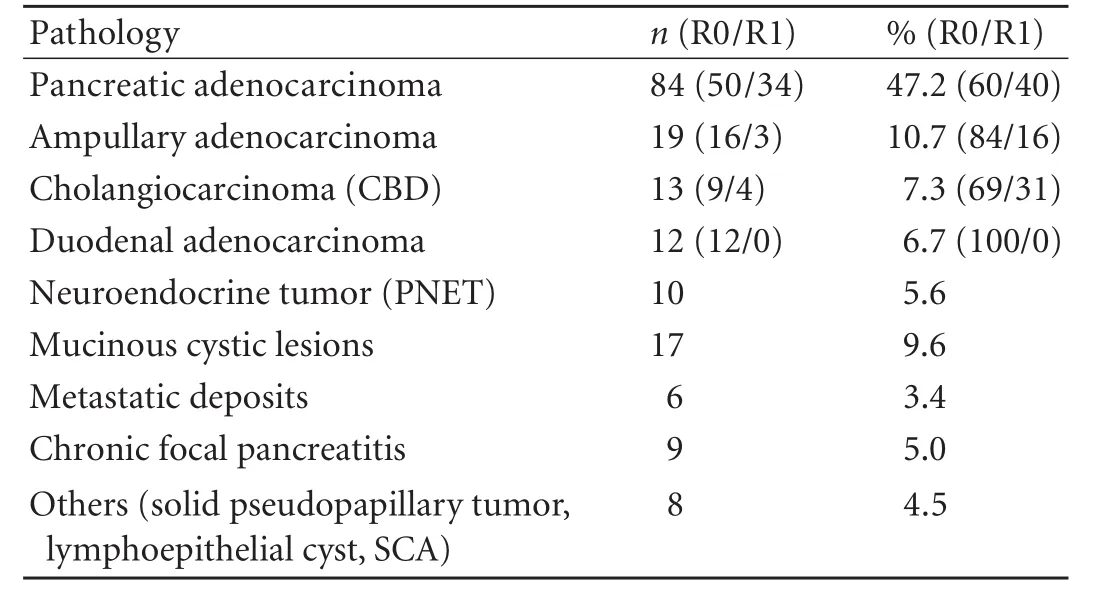

Pancreatoduodenectomy was carried out in the remaining 178 patients and their demographics and pathology are shown in Table 1. The resection rate (pancreatoduodenectomy) for the original cohort was 60%. Twenty-three patients who were not subjected to surgery were older (median age 87 years, range 57-92 years) than those who underwent surgery (median age 67, range 18-88 years) (P<0.0015). The five patients who refused surgery were similar to the cohort who underwent surgery. Sixty-one (61/178, 34%) patients required either a vascular resection or an additional visceral resection. Fifty of these patients underwent PV or SMV resection (28%) and nine had an additional arterial resection of the commonhepatic artery (5%). The final pathology is shown in Table 2 along with the R0, R1 and R2 resection rates for the pancreatic, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and ampullary cancers. The R1 resection rate for all cancers was based on a 1.5 mm tumor clearance.[14]Nine patients underwent pancreatoduodenectomy for what was thought to be malignancy on preoperative investigations; however, the histology post-resection showed focal chronic pancreatitis. No patient with a known preoperative diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis was included in this study and therefore all patients underwent a pancreatoduodenectomy instead of other procedures such as Frey or Beger procedures.

Table 1. Demographic, clinical presentation and ASA data on 178 patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy

Table 2. Pathology and R0/R1 resection data on 178 patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy

Table 3. Complication data on 178 patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy

Eighty-nine (89/178) patients experienced a complication following surgery (Table 3). The commonest complication was the need for blood transfusion (12%). Forty-one patients (23%) required a blood transfusion and 36 (88%) of these had vascular resection. In this group, the median number of units transfused was 2 (range 1-27). The procedure-related complications were pancreatic fistula (9%), delayed gastric emptying (4%) and postoperative hemorrhage (4%). Thirty-four patients (19%) had a major complication, i.e. grade 3 or above. Patients with a major complication had a significantly longer hospital stay (median 26, range 12-44 days) compared with the remainder of the cohort (median 13, range 7-44 days) (P<0.001). Patients without any complications had the shortest median stay (median 12, range 7-20 days). There was no in-hospital mortality. In addition, there were no 30-day or 60-day deaths.

Discussion

The role of pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary cancers was still questioned in the 1990s.[15]It was perceived as a formidable procedure both for the patient and the surgeon. Understandably, there was reluctance among many physicians to refer their patients for surgical opinion. This view has remained deeply entrenched among many physicians. For example, a recent review from the United States showed that up to 40% of patients with early periampullary cancers were not given surgery despite being resectable.[16]There is no reason to believe that the situation is any different in Australasia.

The majority of patients referred for periampullary cancer surgery have advanced tumor at initial presentation and it is essential to have an accurate assessment of the extent of their disease. Often, the initial CT is of poor quality and therefore can underestimate the extent of disease. In our study, a more detailed and dedicated MDCT, when interrogated by a multidisciplinary team, was able to prevent unnecessary further surgical intervention in 21% of patients. The role of MDCT in detecting local vascular invasion[17]as well as liver metastasis[18]has been well established. In the presence of pancreatitis, local vascular invasion can be overestimated. This is not an uncommon finding in the setting of a pancreatic adenocarcinoma, where obstruction of the main pancreatic duct leads to pancreatitis.[19]Unfortunately, this can only be accurately assessed at the time of laparotomy. The addition of laparoscopy remains a useful tool in detecting small-volume peritoneal metastatic disease.[20]This investigation prevented an unnecessary laparotomy in 16 (5%) of our patients. Preoperative imaging, when assessed in the context of a multidisciplinary team, has become the single most important tool in detecting extra-pancreatic disease. The multidisciplinary team is essential to assess every patient with a periampullary tumor to ensure that no patient with a potentially resectable tumor is denied surgery, that surgery is not undertaken in patients without optimum investigation to identify metastatic disease, as well as to identify and plan vascular and adjacent organ resection preoperatively to ensure a greater percentage of R0 resection.

Historically, the resection rate for pancreatic cancer patients has been 5%[21,22]and any variance in this rate usually reflects referral bias.[23]The resection rate of 60% in our series partially reflects referral bias. It is also likely to be due to our aggressive vascular resection policy. In the current series, 28% of all patients had either PV or SMV resection. In the literature, the vascular resection rate for pancreatic adenocarcinoma varies from 6% to 52%,[24,25]compared with 50% in our series.

The pathological assessment of resection margin has been a topical and controversial issue. In the past, only one or two samples were taken along the pancreatic resection margin to define the (R) resection status and as a result the true rate of incomplete (R1 or R2) excision has been underestimated. There is now clear evidence that when resection margins are carefully assessed by an experienced pathologist, and multiple sections are taken of key resection margins (particularly the periuncinate margin), the R1 resection rate can be as high as 76% to 85% even in well-screened patients in experienced large-volume centers.[26,27]Contrary to some literature suggesting that margin status is not an important predictor of survival, there is now good evidence that the presence of a clear margin is a key predictor of survival but only in units where margins are carefully assessed. In short, we suspect that extreme variances in the reported rates of R1 resections may be due to differences in the quality of pathological reporting rather than to differences in surgical technique. It is often the retroperitoneal/periuncinate (SMA) margin which is positive.[27]It is this transection margin which determines local recurrence and survival.[28]We used a clearance of 1.5 mm[14]ratherthan 1.0 mm[29]to define R0 resection. Our unit adopted an aggressive policy as early as 2004 to clear this margin as extensively as possible.[13]This technique allows more soft tissue to be removed from the right-hand margin of the SMA allowing better assessment of neural invasion by the tumor. However, it does not guarantee lower local recurrence, as tumor invasion can occur circumferentially[30]as well as up and down the SMA.[31]Our R1 resection rate for pancreatic adenocarcinoma was 40%, a value similar to the largest single-institution study.[8]This high value reflects the fact that 1.5 mm clearance can be difficult to achieve and that there was rigorous pathological assessment of the margin status. If the 1.5 mm margin criterion was not used and R0 was defined simplistically as the absence of tumor at an inked surgical margin, then the R1 resection rate would have been as low as 12%. It is our belief that many studies, probably including ours, still underestimate the R1 resection rate. It is important to define clear surgical resection reference points so as to standardize the resection process, otherwise comparative data could yield erroneous results. Synoptic pathological reporting which we adopted in 2006[32]can assist this process.

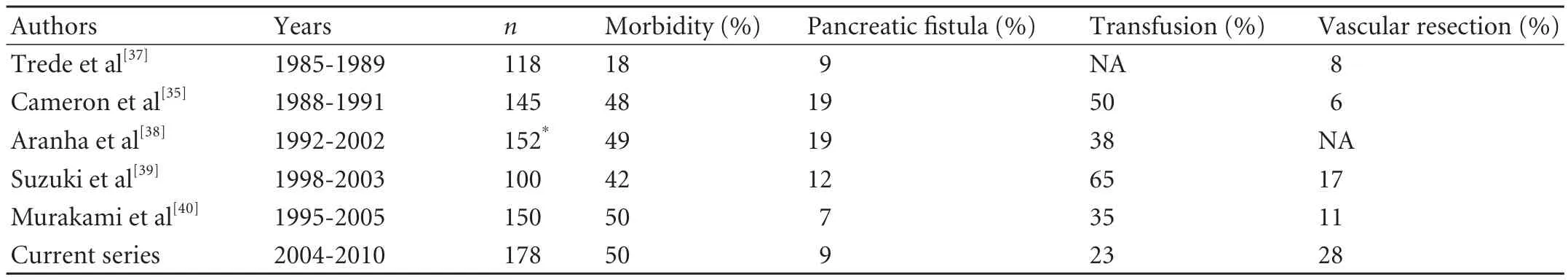

Table 4. Published series including the current series with more than 100 consecutive pancreatoduodenectomies without mortality

The morbidity rate of 50% is similar to the seminal study published on this topic.[33]In the Clavien-Dindo classification, blood transfusion is defined as a grade 2 complication. In our study, at least 10% of the excess morbidity was due to blood transfusion alone. In the absence of transfusion morbidity, the residual morbidity of 40% is similar to other larger prospective studies.[34,35]

There were no perioperative, postoperative or inhospital deaths in this series. This is one of the largest, single-surgeon pancreatoduodenectomy series without mortality. We calculated the 60-day rather than the 30-day mortality as traditionally measured. There is some evidence that the 60-day mortality gives a more accurate assessment of the mortality associated with pancreatic resection.[36]There have been a number of series, with more than 100 consecutive pancreatoduodenectomies, without mortality (Table 4). The series treated by Aranha et al[38]was based on a pancreatoduodenectomy and pancreatogastrostomy. They did not include patients who had pancreaticojejunostomy. There were deaths in the latter group as indicated by their other publications.[41]Table 4 also confirms the trend towards increased vascular resections. More importantly, the morbidity has remained unchanged at 40%. All of these series have come from units where more than 15 pancreatoduodenectomies are performed annually.[42]The relationship between high volume and low mortality following pancreatoduodenectomy has now been well established.[7,43]

In conclusion, pancreatoduodenectomy can be performed safely in high-volume units with a very low mortality. It is inevitable that there is a finite rate of mortality associated with these complex pancreatic resections. The surgeon's role should include careful patient selection, use of intensive preoperative investigations, participation of other team members in the decision-making process, and an unbiased discussion at a multidisciplinary meeting. This approach is likely to optimize outcomes in these patients.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:The study received Hospital approval for auditing of morbidity and mortality.

Contributors:SJS proposed the study. SJS, BRA and CJ collected, analyzed and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the design, interpretation of the study and to further drafts. SJS is the guarantor

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Kausch W. Das Carcinom der Papilla duodeni und seine radikale Entfernung. Beitr Klin Chir 1912;78:439-451.

2 Whipple AO, Parsons WB, Mullins CR. Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Ann Surg 1935;102:763-779.

3 Riall TS, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Winter JM, Campbell KA, Hruban RH, et al. Resected periampullary adenocarcinoma: 5-year survivors and their 6- to 10-year follow-up. Surgery2006;140:764-772.

4 Harrison LE, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF. Isolated portal vein involvement in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A contraindication for resection? Ann Surg 1996;224:342-349.

5 Tseng JF, Raut CP, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection: margin status and survival duration. J Gastrointest Surg 2004;8:935-950.

6 Nakase A, Matsumoto Y, Uchida K, Honjo I. Surgical treatment of cancer of the pancreas and the periampullary region: cumulative results in 57 institutions in Japan. Ann Surg 1977;185:52-57.

7 McPhee JT, Hill JS, Whalen GF, Zayaruzny M, Litwin DE, Sullivan ME, et al. Perioperative mortality for pancreatectomy: a national perspective. Ann Surg 2007;246:246-253.

8 Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Arnold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J, et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: A single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1199-1211.

9 Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13.

10 Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2007;142:761-768.

11 Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-213.

12 Katz MH, Pisters PW, Evans DB, Sun CC, Lee JE, Fleming JB, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: the importance of this emerging stage of disease. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:833-848.

13 Samra JS, Gananadha S, Gill A, Smith RC, Hugh TJ. Modified extended pancreatoduodenectomy: en bloc resection of the peripancreatic retroperitoneal tissue and the head of pancreas. ANZ J Surg 2006;76:1017-1020.

14 Chang DK, Johns AL, Merrett ND, Gill AJ, Colvin EK, Scarlett CJ, et al. Margin clearance and outcome in resected pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2855-2862.

15 Gudjonsson B. Carcinoma of the pancreas: critical analysis of costs, results of resections, and the need for standardized reporting. J Am Coll Surg 1995;181:483-503.

16 Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Talamonti MS. National failure to operate on early stage pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg 2007;246:173-180.

17 Tian H, Mori H, Matsumoto S, Yamada Y, Kiyosue H, Ohta M, et al. Extrapancreatic neural plexus invasion by carcinomas of the pancreatic head region: evaluation using thin-section helical CT. Radiat Med 2007;25:141-147.

18 Ikuta Y, Takamori H, Ikeda O, Tanaka H, Sakamoto Y, Hashimoto D, et al. Detection of liver metastases secondary to pancreatic cancer: utility of combined helical computed tomography during arterial portography with biphasic computed tomography-assisted hepatic arteriography. J Gastroenterol 2010;45:1241-1246.

19 Suda K, Takase M, Takei K, Kumasaka T, Suzuki F. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical studies on the mechanism of interlobular fibrosis of the pancreas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000;124:1302-1305.

20 John TG, Greig JD, Carter DC, Garden OJ. Carcinoma of the pancreatic head and periampullary region. Tumor staging with laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasonography. Ann Surg 1995;221:156-164.

21 Bramhall SR, Allum WH, Jones AG, Allwood A, Cummins C, Neoptolemos JP. Treatment and survival in 13,560 patients with pancreatic cancer, and incidence of the disease, in the West Midlands: an epidemiological study. Br J Surg 1995;82: 111-115.

22 Sener SF, Fremgen A, Menck HR, Winchester DP. Pancreatic cancer: a report of treatment and survival trends for 100 313 patients diagnosed from 1985-1995, using the National Cancer Database. J Am Coll Surg 1999;189:1-7.

23 Imaizumi T, Hanyu F, Harada N, Hatori T, Fukuda A. Extended radical Whipple resection for cancer of the pancreatic head: operative procedure and results. Dig Surg 1998;15:299-307.

24 Martin RC 2nd, Scoggins CR, Egnatashvili V, Staley CA, McMasters KM, Kooby DA. Arterial and venous resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: operative and long-term outcomes. Arch Surg 2009;144:154-159.

25 Carrère N, Sauvanet A, Goere D, Kianmanesh R, Vullierme MP, Couvelard A, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with mesentericoportal vein resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. World J Surg 2006;30:1526-1535.

26 Verbeke CS, Leitch D, Menon KV, McMahon MJ, Guillou PJ, Anthoney A. Redefining the R1 resection in pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2006;93:1232-1237.

27 Esposito I, Kleeff J, Bergmann F, Reiser C, Herpel E, Friess H, et al. Most pancreatic cancer resections are R1 resections. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1651-1660.

28 Jamieson NB, Foulis AK, Oien KA, Going JJ, Glen P, Dickson EJ, et al. Positive mobilization margins alone do not influence survival following pancreatico-duodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2010;251:1003-1010.

29 Campbell F, Smith RA, Whelan P, Sutton R, Raraty M, Neoptolemos JP, et al. Classification of R1 resections for pancreatic cancer: the prognostic relevance of tumour involvement within 1 mm of a resection margin. Histopathology 2009;55:277-283.

30 Noto M, Miwa K, Kitagawa H, Kayahara M, Takamura H, Shimizu K, et al. Pancreas head carcinoma: frequency of invasion to soft tissue adherent to the superior mesenteric artery. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1056-1061.

31 Kayahara M, Nakagawara H, Kitagawa H, Ohta T. The nature of neural invasion by pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 2007;35: 218-223.

32 Gill AJ, Johns AL, Eckstein R, Samra JS, Kaufman A, Chang DK, et al. Synoptic reporting improves histopathological assessment of pancreatic resection specimens. Pathology 2009;41:161-167.

33 DeOliveira ML, Winter JM, Schafer M, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, et al. Assessment of complications after pancreatic surgery: A novel grading system applied to 633 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 2006;244:931-939.

34 Müller SA, Hartel M, Mehrabi A, Welsch T, Martin DJ, Hinz U, et al. Vascular resection in pancreatic cancer surgery: survival determinants. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:784-792.

35 Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA. One thousandconsecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg 2006;244: 10-15.

36 Carroll JE, Smith JK, Simons JP, Murphy MM, Ng SC, Shah SA, et al. Redefining mortality after pancreatic cancer resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:1701-1708.

37 Trede M, Schwall G, Saeger HD. Survival after pancreatoduodenectomy. 118 consecutive resections without an operative mortality. Ann Surg 1990;211:447-458.

38 Aranha GV, Hodul PJ, Creech S, Jacobs W. Zero mortality after 152 consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies with pancreaticogastrostomy. J Am Coll Surg 2003;197:223-232.

39 Suzuki Y, Fujino Y, Ajiki T, Ueda T, Sakai T, Tanioka Y, et al. No mortality among 100 consecutive pancreaticoduodenect omies in a middle-volume center. World J Surg 2005;29:1409-1414.

40 Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Nakagawa N, et al. No mortality after 150 consecutive pancreatoduodenctomies with duct-to-mucosa pancreaticogastrostomy. J Surg Oncol 2008;97:205-209.

41 Aranha GV, Hodul P, Golts E, Oh D, Pickleman J, Creech S. A comparison of pancreaticogastrostomy and pancreaticojejunostomy following pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2003;7:672-682.

42 Lieberman MD, Kilburn H, Lindsey M, Brennan MF. Relation of perioperative deaths to hospital volume among patients undergoing pancreatic resection for malignancy. Ann Surg 1995;222:638-645.

43 Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1128-1137.

Received March 8, 2011

Accepted after revision May 25, 2011

Author Affiliations: Upper Gastrointestinal Surgical Unit (Samra JS, Bachmann RA, Choi J, Gananadha S and Hugh TJ), Department of Anatomical Pathology (Gill A), Department of Vascular Surgery (Neale M and Puttaswamy V), Department of Gastroenterology (Bell C, Nortoniand Cho S), and Department of Radiology (Blome S and Maher R), University of Sydney, Royal North Shore Hospital, St Leonards, NSW 2065, Sydney, Australia

Jaswinder S Samra, MD, Suite 1, Level 4, AMA House, 69 Christie St, NSW 2065, Sydney, Australia (Tel: 61-2-94363775; Fax: 61-2-94382278; Email: jaswinder.samra@optusnet.com.au)

© 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Risk factors of severe ischemic biliary complications after liver transplantation

- Health-related quality of life in living liver donors after transplantation

- Surgical treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome: analysis of 221 cases

- Efficacy of liver transplantation for acute hepatic failure: a single-center experience

- Combined invagination and duct-to-mucosa techniques with modifications: a new method of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis

- Large regenerative nodules in a patient with Budd-Chiari syndrome after TIPS positioning while on the liver transplantation list diagnosed by Gd-EOB-DTPA MRI