Changing clinical profile, management strategies and outcome of patients with biliary tract injuries at a tertiary care center in Sri Lanka

2011-07-03JasinArachchigeSamanBingumalJayasundaraWaradanaMohanMalithdeSilvaandAjithAlokaPathirana

Jasin Arachchige Saman Bingumal Jayasundara, Waradana Mohan Malith de Silva and Ajith Aloka Pathirana

Kalubowila, Sri Lanka

Changing clinical profile, management strategies and outcome of patients with biliary tract injuries at a tertiary care center in Sri Lanka

Jasin Arachchige Saman Bingumal Jayasundara, Waradana Mohan Malith de Silva and Ajith Aloka Pathirana

Kalubowila, Sri Lanka

BACKGROUND:Biliary tract injuries are mostly iatrogenic. Related data are limited in developing countries. There are lessons to be learned by revisiting the clinical profiles, management issues and outcome of patients referred to a tertiary care center in Sri Lanka, compared with the previous data from the same center published in 2006. Such a review is particularly relevant at a time of changing global perceptions of iatrogenic biliary injuries. This study aimed to analyze and compare the changes in the injury pattern, management and outcome following biliary tract injury in a Sri Lankan study population treated at a tertiary care center.

METHODS:A retrospective analysis was made of 67 patients treated between May 2002 and February 2011. The profiles of the last 38 patients treated from October 2006 to February 2011 were compared with those of the first 29 patients treated from May 2002 to September 2006. Definitive management options included endoscopic biliary stenting, reconstructive hepaticojejunostomy with creation of gastric access loops, and biliary stricture dilation. Post-treatment jaundice, cholangitis and abdominal pain needing intervention were considered as treatment failures.

RESULTS:In the 67 patients, 55 were women and 12 men. Their mean age was 40.6 (range 19-80) years. Five patients had traumatic injuries. Thirty-seven injuries (23 during the second study period) were due to laparoscopic cholecystectomy and 25 (10 during the second study period) to open cholecystectomy. The identification rate of intra-operative injury was 19% in the laparoscopic group and 8% in the open group. Bismuth typeI, II, III and IV injuries were seen in 18, 18, 15 and 12 patients, respectively. Endoscopic stenting was the definitive treatment in 20 patients. In 35 patients who had hepaticojejunostomy, 33 underwent creation of the gastric access loop. Twentytwo reconstructions were performed during the second study period. A gastric access loop was used for endotherapy in three patients with anastomotic occlusion at the site of hepaticojejunostomy. The overall outcome was satisfactory in the majority of patients. There were four injury-related deaths.CONCLUSIONS:Biliary tract injuries associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy have become the most frequent cause of biliary injury management at our center. Although endotherapy was useful in selected patients, in the majority, surgical reconstruction with hepaticojejunostomy was required as the definitive treatment. Creation of the gastric access loop was found to be a useful adjunct in the management of hepaticojejunostomy strictures.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 526-532)

gastric access loop; hepaticojejunostomy; endoscopic biliary stenting; biliary tract injuries

Introduction

Biliary tract injuries create a management challenge to the surgeon.[1]Iatrogenic injury during cholecystectomy is the most common etiological factor, while penetrating and blunt abdominal trauma is reported to cause biliary injury at a lesser frequency.[1,2]Initial extravasation of bile leads to biliary peritonitis and sepsis.[1-3]Subsequent bile duct strictures cause obstructive jaundice, suppurative cholangitis, and liver abscess formation and if unattended, leads to secondary biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension. These complications carry a significant morbidity and mortality.[1,4]

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is currentlyaccepted as the gold standard treatment for symptomatic gallstone disease. It has gained evidence-based superiority over open cholecystectomy (OC).[1,4-6]Despite two decades of experience, LC still carries a 2-2.5 times higher risk of bile duct injury than its open counterpart.[1,2,7-10]Primary suture repair, repair over a T-tube, endoscopic stenting and reconstructive surgery with hepatico/choledochojejunostomy are the available management options for iatrogenic biliary injuries.[1-3,11]These procedures require considerable surgical and endotherapeutic expertise. However, all such options carry a considerable morbidity, treatment failure and mortality.[1,2,4,12]Management at specialized centers has been shown to improve the outcome.[2,3]

There is paucity of data related to bile duct injuries in developing countries. As a tertiary care referral center with a special interest in hepatobiliary surgery, we reported our initial experience of managing biliary injuries in 2006.[13]In that study, the majority of injuries were found to have occurred following OC, and reconstructive hepaticojejunostomy and endoscopic stenting were found equally effective in the management of selected cases.

The global perception of iatrogenic biliary injury is evolving.[2,14,15]Much is published on the quality of life and medico-legal aspects following such injuries.[16,17]A revisit to the database is useful to identify changes in the injury profile, management strategies and outcome after management of biliary injuries in Sri Lanka, as compared with the previous report.[13]This study aimed to analyze and compare the changes in the injury pattern, management strategies and outcome following bile duct injury in a Sri Lankan study population treated at a tertiary care referral center.

Methods

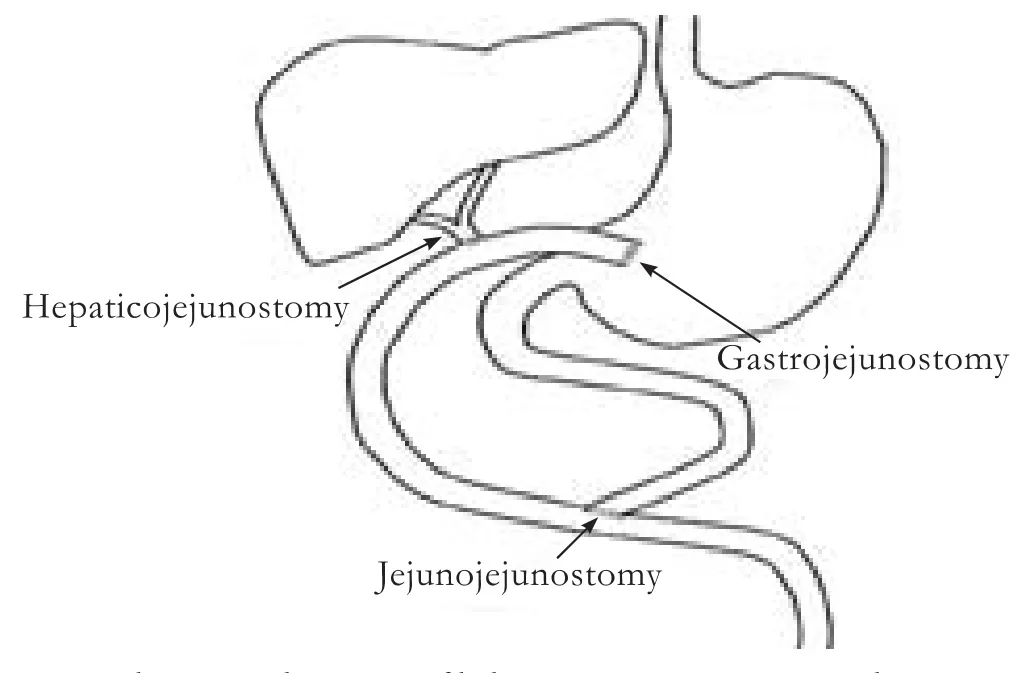

The data of 67 consecutive patients referred to the University Surgical Unit, Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila, from May 2002 to February 2011 for the management of bile duct injuries were retrospectively analyzed. The profiles of the last 38 patients treated in the second study period between October 2006 and February 2011 (52 months) were compared with those of the first 29 patients treated in the study period between May 2002 and September 2006 (52 months).[13]The data were reviewed with regard to the etiology of injury, patient demographics, type of injury, management and outcome following a definitive treatment. The Bismuth classification was used to classify the injuries according to the results of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) as well as intra-operative findings. Most patients underwent ERC, and those, who had lateral wall defects and in whom the guide wire could access the proximal bile duct segment through the stricture or the injury site, had biliary stenting. Patients who had complete "cutoffs", those with strictures not responding to endotherapy, and those with strictures at a previous hepaticojejunostomy site underwent PTC to evaluate the proximal biliary tract. They were given reconstructive hepaticojejunostomy as a definitive treatment. All except two hepaticojejunostomies were accompanied by creation of the gastric access loop (Fig. 1).[18]

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of biliary reconstruction with a gastric access loop.

Patients who had endoscopic stenting were evaluated by ERC at three-month intervals and had stent removal or stricture dilation and re-stenting. After stent removal, asymptomatic patients were reviewed every three months for one year before being discharged from follow-up. If symptomatic, they were reviewed more frequently and managed appropriately by stricture dilation with stenting or reconstructive surgery. Patients who had hepaticojejunostomy were reviewed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery and annually thereafter. Follow-up was based on clinical evaluation and liver function tests. Ultrasonography, computed tomography, PTC or isotope scanning was performed when indicated. Post-treatment jaundice, cholangitis or recurrent abdominal pain requiring intervention were considered as treatment failures.

Patients with anastomotic site occlusion underwent stricture dilation through a gastric access loop or had revision surgery. All surgical and endotherapeutic procedures were performed after informed written consent was obtained from the patients. During the period of surveillance other than the planned review visits, all patients were given open access to the weekly clinic if they have any problems.

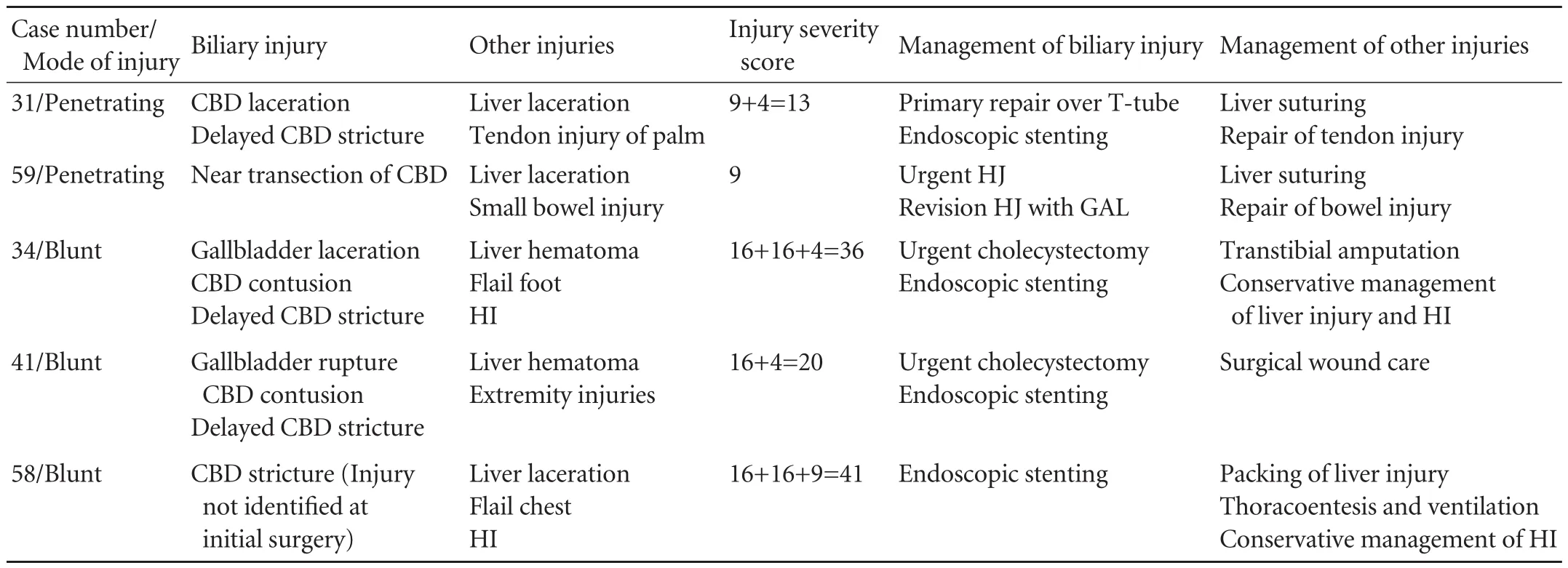

Table 1. Details of traumatic biliary injuries

Outcome assessment was based on the clinical records and investigations available on the last clinic review when it was within six months from February 2011 (29 patients). Patients who had been discharged from follow-up and those who were on annual follow-up and not reviewed within six months from February 2011 were called to be reviewed (10 patients) or symptom assessment was done over the telephone (13 patients). Thirty-three patients in the hepaticojejunostomy group and 19 in the endotherapy group were evaluated.

Results

Demographics

This study consisted of 55 women and 12 men, whose mean age was 40.6 (range 19-80) years. Five patients had traumatic injuries and the rest had iatrogenic injuries. Thirty-seven patients with injuries were due to LC performed as an elective procedure. Ten of these operations were subsequently converted to open surgery. Five patients were subjected to primary repair or reconstruction, but in the rest, the injury was not identified. All traumatic injuries and 23 LC-related injuries were referred during the second study period. Twenty-five injuries were due to OC. Four patients in this group underwent bile duct exploration and one had surgery as an emergency. Only 10 OC-related biliary injuries were referred during the second study period. In the iatrogenic injury category, except for one OC performed by a surgical trainee, all cholecystectomies were performed by consultant surgeons.

Presentation

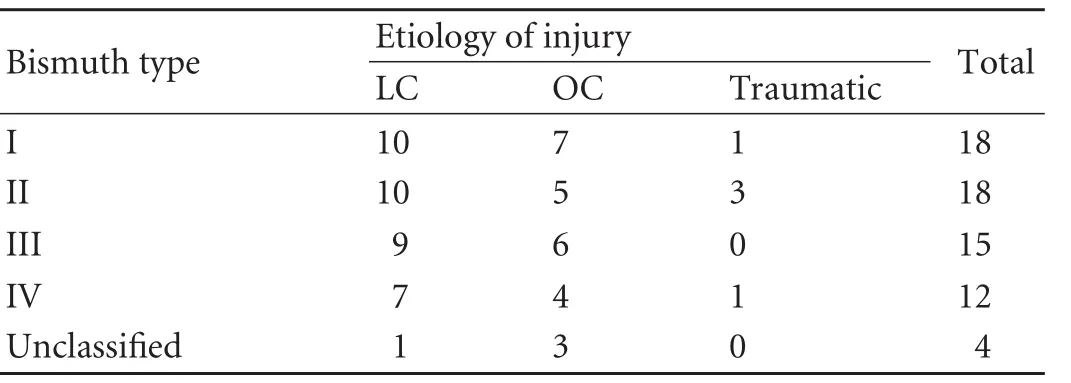

Table 2. Bismuth classification of the injuries

In the traumatic category, three patients had blunt abdominal trauma and the other two had penetrating stab injuries. The patients with blunt trauma showed evidence of biliary obstruction within two weeks. Of the two patients with penetrating injuries, one who had a partial injury to the common bile duct presented with a stricture two months after initial repair over a T-tube. The other, who had a hepaticojejunostomy for a near complete transection of the common bile duct, presented with an anastomotic stricture three months after surgery (Table 1).

Of the patients with iatrogenic category, 9 patients with injuries were identified intraoperatively. The injury identification rate was 19% in the laparoscopic group and 8% in the open group.

Type of injury according to Bismuth classification (Table 2)

ERC was performed in 54 patients. In 24 patients, endoscopic stenting was performed. Twenty-eight patients needed PTC for further evaluation of the injury. Injuries were classified by ERC, PTC and intra-operative findings.

Treatment and follow-up

Endotherapy was the definitive treatment in 20 out of 24 patients who had endoscopic stenting. The majority of these patients had Bismuth typeiand II injuries (Table 3). Stent was removed after exchange of one or two stents. All patients were asymptomatic for more than one year after stent removal except one who have been followed up only for nine months. A lady who developed an advanced ovarian carcinoma was not subjected to stent removal and she died eight months after biliary stenting because of deterioration of malignancy. A lower percentage of patients showed successful endotherapy during the second study period. Four of the 24 patients who had initially received endotherapy required biliaryenteric reconstruction during this period because of tight strictures resistant to dilation after a mean of three stent exchanges. These patients developed frequent episodes of cholangitis despite stricture dilation and stent exchanges (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram of a tight biliary stricture which required surgical reconstruction after five stent exchanges.

Table 3. Management options according to Bismuth type of injury

Thirty-five patients underwent hepaticojejunostomy as a definitive reconstructive operation. In this group, the Bismuth level of the injury was more severe than that in the endotherapy group (Table 3). Thirtythree of these reconstructions were accompanied by creation of a gastric access loop including four revision operations and one re-revision operation. The stricture of hepaticojejunostomy site with no therapeutic access to the anastomosis indicated for revision operation. Two patients were lost to follow-up three and nine months after reconstructive surgery. The rest of the patients had a mean follow-up of 37.1 (range 1-90) months. Compared with 13 reconstructions performed during the first study period, 22 hepaticojejunostomies were performed during the second study period. In this period, three patients developed anastomotic occlusion at 4, 22 and 5 months after hepaticojejunostomy and were treated successfully with endotherapy via a gastric access loop. The first patient underwent stricture dilation by stenting, the second had balloon sweepingfor hepaticolithiasis, and the third had stricture dilation. All of the three patients had satisfactory outcomes after endotherapy (Fig. 3). The other patients were asymptomatic following biliary reconstruction. One patient is awaiting for a hepaticojejunostomy.

Fig. 3. Endoscopic view of a hepaticojejunostomy stricture through a gastric access loop.

Table 4. Management options during the two study periods

Seven patients were referred back to the initial center after ERC, as requested. The management options during the two study periods are listed in Table 4.

Outcome after treatment

All 19 reviewed patients who had undergone endotherapy as a definitive treatment had satisfactory outcomes. Thirty (91%) patients showed satisfactory outcomes after reconstructive hepaticojejunostomy. Three who developed stricture of hepaticojejunostomy site had good outcomes after endotherapeutic intervention via a gastric access loop.

Mortality

Four patients died within one month of biliary injury. Three patients (aged 28, 38 and 72 years) with iatrogenic injuries after LC died of initial biliary sepsis. One patient with blunt abdominal trauma associated with hepatobiliary injury died from septic thrombosis of the hepatic vein and inferior vena cava.

Discussion

Most of the biliary injuries were iatrogenic. Out of the 29 iatrogenic injuries reported in the first study published in 2006, 14 (48%) occurred following the laparoscopic approach.[13]During the second study period, 70% of iatrogenic injuries occurred after LC. The increased availability of laparoscopic surgery and the learning curve effect may be responsible for the higher number of laparoscopic biliary injuries observed during the second period.

Our intra-operative injury identification was 19% in the LC group and 8% in the OC group. Studies have reported an intra-operative injury identification rate around 30% for LC.[1,3,8]We found that intra-operative cholangiography (IOC) had not been performed in all patients referred after iatrogenic biliary injuries. Although there is no evidence that IOC prevents bile duct injuries, several studies have shown that IOC during LC increases the intra-operative injury identification rate.[10,19-21]

The reported incidence of non-iatrogenic injury to the extra-hepatic biliary tree ranges between 1% and 5% of patients who sustain blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma.[22,23]Isolated injury to the extra-hepatic biliary tree is uncommon. The liver is the most commonly injured organ and the gallbladder is the most frequently injured segment of the biliary tree.[22-24]Traumatic bile duct injuries include partial or complete transections and contusions. All our patients had developed biliary or anastomotic strictures by the time they were referred. The profile of our series is compatible with the published data.

Studies have shown similar long-term success rates of endotherapy and surgery in the management of benign biliary strictures.[11]ERC helps to identify the site and severity of the injury and stenting is useful to abort bile leaks in partial bile duct injuries. Nineteen (29%) patients who received endotherapy in our series showed good outcomes with a mean follow-up of 45.7 months. Endotherapy is effective in reducing the psychological fear of the patient and the family, and helped to downgrade the crisis situation. It is also helpful as a confidence-building measure with assurance of recovery, and therefore the subsequent treatment. Costamagna et al[25]reported good longterm outcomes of patients treated with endotherapy with multiple stenting. Three patients in our series had double stents with good outcomes. In all, four patients who were primarily treated with endotherapy with good immediate and short-term outcomes subsequently needed reconstructive surgery due to the recurrence of strictures in spite of repeated dilations. They had recurrent episodes of cholangitis and required repeated stent exchanges, and reconstructive surgery was carried out to alleviate the problem. Our results indicate that endoscopic stricture dilation is useful in the overall management of biliary injuries although the probability of stricture formation continues to remain after "successful" endotherapy.

Most of the patients require hepaticojejunostomy reconstruction. It is interesting to note that out of the 34 patients who underwent hepaticojejunostomy for iatrogenic injuries, 20 (59%) had the injury induced by the laparoscopic approach.

Provision of an access to hepaticojejunostomy anastomosis was considered as mandatory during biliary reconstruction in our series. Biliary enteric anastomoses are found to be prone to subsequent occlusion even in the hands of experts.[4,12,18]Untreated hepaticojejunostomy strictures can lead to long-term complications such as hepaticolithiasis, cholangitis, liver abscess formation, secondary biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension.[26]Revision surgery is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. We preferred the gastric access loop over the conventional jejunal access loop. Limitations of advanced radiological facilities andlimited availability of therapeutic radiologists required us to create gastric access. The gastric access loop provided us an opportunity to intervene and perform successful endoscopic stricture dilation in three patients and helped to avoid major revision surgery in our series. Perakath et al[27]reported the first successful therapeutic use of the gastric access loop. The loop was first described by Sitaram et al in 10 patients and access to the hepaticojejunostomy site was possible in five.[18]Selvakumar et al[4]reported a retrospective analysis of 13 patients with a gastric access loop. The loop was accessible in only eight patients. Access was not possible in a patient who developed a hepaticojejunostomy stricture, due to a tight gastrojejunostomy stricture resistant to repeated balloon dilation. Possible bile reflux to the stomach in the presence of a gastric access loop leading to biliary dyspepsia was a concern to many surgeons. In a recent publication from our group, we objectively evaluated the issue using an analog scoring system (dyspepsia disability score).[28]The cohort of patients with a gastric access loop did not suffer from disabling biliary dyspepsia after a mean follow-up of 35.4 months following surgery and limited endoscopic evaluation and histological assessment excluded gastritis or peptic ulceration.[28]

In conclusion, the present study highlights that LC-associated biliary tract injury is the most frequent cause of biliary injury referred to hospitals, the majority requiring reconstructive surgery. In selected patients with less severe injuries, endotherapy was successful when biliary-enteric integrity was found to be intact. Therapeutic strategies changed in some patients who were initially treated with endotherapy as a "definitive" treatment, who subsequently needed open surgery. Provision of a gastric access loop was found to be a useful adjunct. We recommend the creation of gastric access which we found useful in the treatment of hepaticojejunostomy stricture in settings with limited availability of interventional radiological facilities.

Acknowledgement

We thank Mr. IWPM Wanigasooriya for assistance in data collection and maintaining the database.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Contributors:JJASB proposed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the first draft under the supervision of dSWMM and PAA. dSWMM and PAA edited the final draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. JJASB is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 McPartland KJ, Pomposelli JJ. Iatrogenic biliary injuries: classification, identification, and management. Surg Clin North Am 2008;88:1329-1343; ix.

2 Lillemoe KD. Current management of bile duct injury. Br J Surg 2008;95:403-405.

3 Lillemoe KD. Evaluation of suspected bile duct injuries. Surg Endosc 2006;20:1638-1643.

4 Selvakumar E, Rajendran S, Balachandar TG, Kannan DG, Jeswanth S, Ravichandran P, et al. Long-term outcome of gastric access loop in hepaticojejunostomy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2008;7:152-155.

5 Jenkins PJ, Paterson HM, Parks RW, Garden OJ. Open cholecystectomy in the laparoscopic era. Br J Surg 2007;94: 1382-1385.

6 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement on Gallstones and Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Am J Surg 1993;165:390-398.

7 A prospective analysis of 1518 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. The Southern Surgeons Club. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1073-1078.

8 Adamsen S, Hansen OH, Funch-Jensen P, Schulze S, Stage JG, Wara P. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective nationwide series. J Am Coll Surg 1997;184:571-578.

9 Hasl DM, Ruiz OR, Baumert J, Gerace C, Matyas JA, Taylor PH, et al. A prospective study of bile leaks after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2001;15:1299-1300.

10 Deziel DJ, Millikan KW, Economou SG, Doolas A, Ko ST, Airan MC. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a national survey of 4,292 hospitals and an analysis of 77 604 cases. Am J Surg 1993;165:9-14.

11 Davids PH, Tanka AK, Rauws EA, van Gulik TM, van Leeuwen DJ, de Wit LT, et al. Benign biliary strictures. Surgery or endoscopy? Ann Surg 1993;217:237-243.

12 Al-Ghnaniem R, Benjamin IS. Long-term outcome of hepaticojejunostomy with routine access loop formation following iatrogenic bile duct injury. Br J Surg 2002;89:1118-1124.

13 De Silva WM, Sivananthan S, De Silva D, Fernando N. Biliary tract injury during cholecystectomy: a retrospective descriptive review of clinical features, treatment and outcome. Ceylon Med J 2006;51:132-136.

14 Savader SJ, Lillemoe KD, Prescott CA, Winick AB, Venbrux AC, Lund GB, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy-related bile duct injuries: a health and financial disaster. Ann Surg 1997;225:268-273.

15 Moore DE, Feurer ID, Holzman MD, Wudel LJ, Strickland C, Gorden DL, et al. Long-term detrimental effect of bile duct injury on health-related quality of life. Arch Surg 2004;139: 476-482.

16 Kern KA. Malpractice litigation involving laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cost, cause, and consequences. Arch Surg 1997;132:392-398.

17 Gouma DJ, Obertop H. Quality of life after repair of bile ductinjury. Br J Surg 2002;89:385-386.

18 Sitaram V, Perakath B, Chacko A, Ramakrishna BS, Kurian G, Khanduri P. Gastric access loop in hepaticojejunostomy. Br J Surg 1998;85:110.

19 Branum G, Schmitt C, Baillie J, Suhocki P, Baker M, Davidoff A, et al. Management of major biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 1993;217:532-541.

20 Woods MS, Traverso LW, Kozarek RA, Tsao J, Rossi RL, Gough D, et al. Characteristics of biliary tract complications during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a multi-institutional study. Am J Surg 1994;167:27-34.

21 Berci G, Sackier JM, Paz-Partlow M. Routine or selected intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Am J Surg 1991;161:355-360.

22 Parks RW, Diamond T. Non-surgical trauma to the extrahepatic biliary tract. Br J Surg 1995;82:1303-1310.

23 McNabney WK, Rudek R, Pemberton LB. The significance of gallbladder trauma. J Emerg Med 1990;8:277-280.

24 Bade PG, Thomson SR, Hirshberg A, Robbs JV. Surgical options in traumatic injury to the extrahepatic biliary tract. Br J Surg 1989;76:256-258.

25 Costamagna G, Tringali A, Mutignani M, Perri V, Spada C, PandolfiM, et al. Endotherapy of postoperative biliary strictures with multiple stents: results after more than 10 years of follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:551-557.

26 Blumgart LH, Kelley CJ, Benjamin IS. Benign bile duct stricture following cholecystectomy: critical factors in management. Br J Surg 1984;71:836-843.

27 Perakath B, Sitaram V, Mathew G, Khanduri P. Postcholecystectomy benign biliary stricture with portal hypertension: is a portosystemic shunt before hepaticojejunostomy necessary? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2003;85:317-320.

28 Jayasundara JA, de Silva WM, Pathirana AA. Therapeutic value and outcome of gastric access loops created during hepaticojejunostomy for iatrogenic bile duct injuries. Surgeon 2010;8:325-329.

Received February 8, 2011

Accepted after revision July 11, 2011

As knowledge increases, wonder deepens.

—Charles Morgan

Author Affiliations: University Surgical Unit, Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila, Sri Lanka (Jayasundara JASB, de Silva WMM and Pathirana AA)

Jasin Arachchige Saman Bingumal Jayasundara, MBBS, 4/7D, First Lane, Ananda Maithrie Mawatha, Maharagama, Sri Lanka (Tel: 0094714187835; Email: bingumal@sltnet.lk)

© 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(11)60089-1

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Protective effect of clodronate-containing liposomes on intestinal mucosal injury in rats with severe acute pancreatitis

- Collagen proportionate area of liver tissue determined by digital image analysis in patients with HBV-related decompensated cirrhosis

- Evaluation outcomes of donors in living donor liver transplantation: a single-center analysis of 132 donors

- Salvianolic acid B modulates the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes in HepG2 cells

- Protective effect of probiotics on intestinal barrier function in malnourished rats after liver transplantation