Frequency and safety of COVID-19 vaccination in children with multisystem inf lammatory syndrome: a telephonic interview-based analysis

2022-11-08KubraAykacKubraOzturkOsmanOguzDemirDilanDemirGumusSevgiAslanElaCemMirayYilmazCelebiMustafaDoganKarabacakGulsumAlkanFatmaDilsadAksoyBurcuCeylanCuraaYylaEdaKepenekliSolmazCelebiMelikeEmirogluIlkerDevrimAliBulentCengiz

Kubra Aykac · Kubra Ozturk · Osman Oguz Demir · Dilan Demir Gumus · Sevgi Aslan · Ela Cem ·Miray Yilmaz Celebi · Mustafa Dogan Karabacak · Gulsum Alkan · Fatma Dilsad Aksoy · Burcu Ceylan Cura aYyla ·Eda Kepenekli · Solmaz Celebi · Melike Emiroglu · Ilker Devrim · Ali Bulent Cengiz · Mehmet Ceyhan ·Yasemin Ozsurekci

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines are currently approved or authorized to prevent serious outcomes,such as severe disease, hospitalization, and death. The Pf izer-BioNTech vaccine is recommended for everyone aged f ive and older in the United States (US) to prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection[ 1, 2]. However, it is unclear whether children with a history of multisystem, inf lammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)may be at risk for a MIS-like response following COVID-19 vaccination or SARS-CoV-2 reinfection [ 2]. Therefore, physicians remain uncertain about vaccinating children with a history of MIS-C. This study investigates the occurrence of severe, systemic side eff ects of COVID-19 vaccines and the recurrence of the MIS-C symptoms in children with a history of MIS-C to overcome vaccine hesitancy.

We recruited children with a history of MIS-C diagnosed between April 2020 and December 2021 in seven hospitals in diff erent regions of Turkey. Our study included three groups of children: (1) those with a history of MIS-C who met the US Center for Disease Control (CDC) or World Health Organization def initions for MIS-C [ 3, 4]; (2) those with a history of severe/critical COVID-19 [ 5]; (3) and those visiting hospitals for another reason and had no history of severe/critical COVID-19 or MIS-C (controls). Children were called by phone and were asked to complete a questionnaire. We checked their vaccination status in the mobile application developed by the Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health to inform and guide citizens about COVID-19. Turkey authorized the Pf izer-BioNTech (mRNA) and Sinovac (inactivated virus) vaccines only for children aged 12 years or older.

We developed a questionnaire including questions adopted from previous studies and new questions related to vaccine side eff ects reported by the CDC [ 6, 7]. Children with a MIS-C and severe/critical COVID-19 diagnosis and children without a MIS-C or severe/critical COVID-19 history were called by phone and were asked a standard set of questions that included their age, gender, and COVID-19 vaccination status. If the child had received a COVID-19 vaccination, we asked about the date of vaccination, the brand of the vaccine given, doses, side eff ects experienced (including their date and duration), polyclinic visit, and hospitalization. Children were asked about local and systemic reactions. Parents were asked questions about factors aff ecting their vaccination decision, including infection or reinfection anxiety in their family,information disseminated via social media, and advice from schools, friends, doctors, and the healthcare ministry.

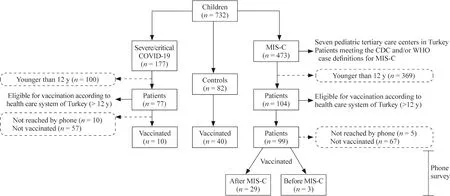

A total of 732 children were evaluated during the study period (Fig. 1). Among the 99 children with a history of MIS-C, 29 (29.2%) were vaccinated for COVID-19 despite their history of MIS-C. Among the 67 children with a history of severe COVID-19, only 10 (14.9%) were vaccinated for COVID-19. Among the 82 control children, 40 (48.7%)were vaccinated for COVID-19.

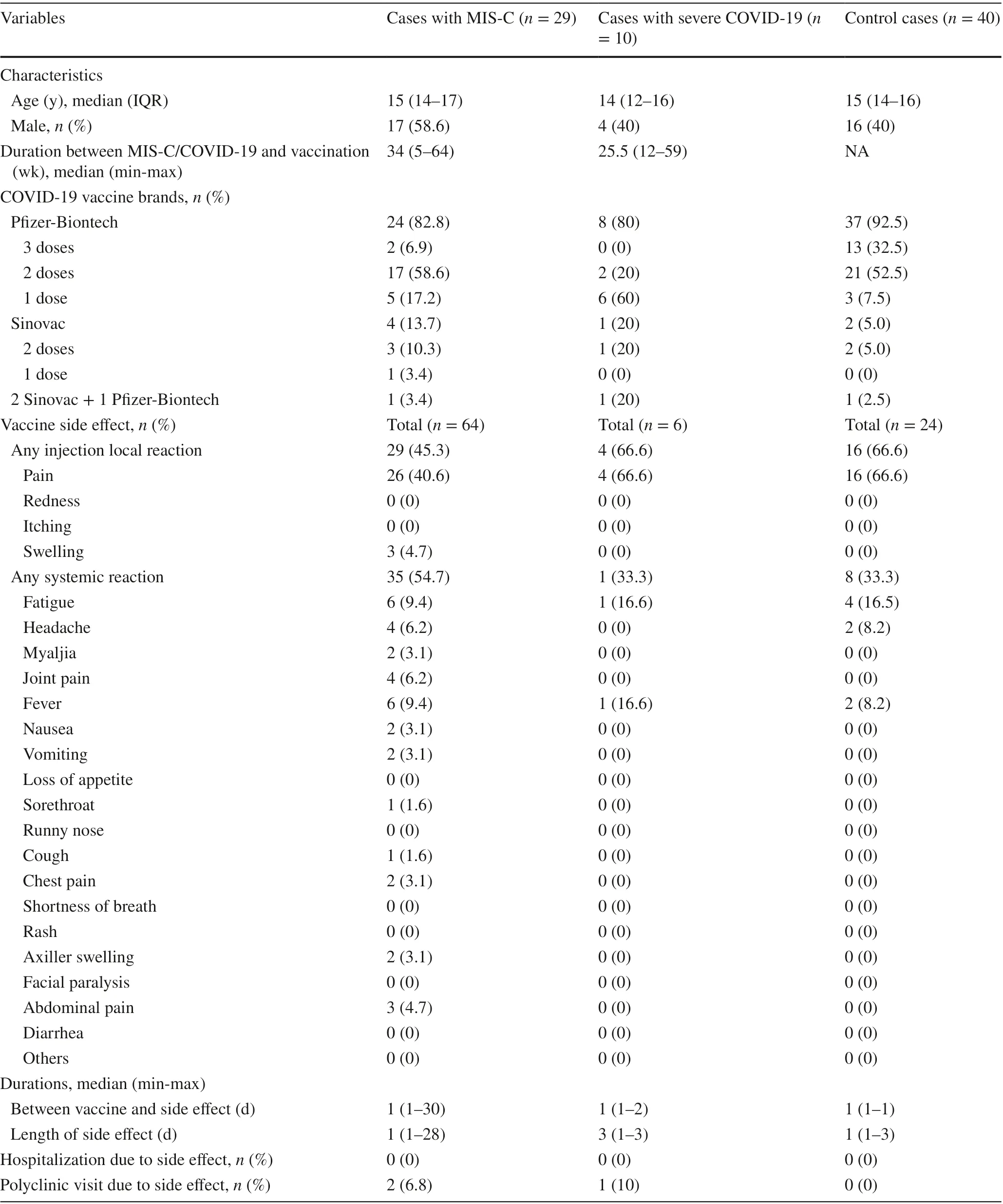

While 29 children with a history of MIS-C received 1—3 doses of a COVID-19 vaccine after their MIS-C diagnosis,three were vaccinated before their MIS-C diagnosis. Only 6.9% had received three doses, 58.6% had received two doses, 17.2% had received one dose of the Pf izer-BioNTech vaccine, and 13.7% had received 1—2 doses of the Sinovac vaccine. In addition, one child had received two doses of the Sinovac vaccine and one booster dose of the Pf izer-BioNTech vaccine. However, 67 (67.7%) have not yet been vaccinated for COVID-19. Among the 77 children with a history of severe COVID-19, two had received two doses and six had received one dose of the Pf izer-BioNTech vaccine, while one had received two doses of the Sinovac vaccine. Among the 82 control children, 40 (48.7%) had been vaccinated for COVID-19. Of these, 13 (32.5%) had received three doses, 21 (52.5%) had received two doses, and 3 (7.5%) had received one dose of the Pf izer-BioNTech vaccine, while 2(5%) had received two doses of the Sinovac vaccine.

There were 64 side eff ects reported across 53 vaccine doses in 29 children with MIS-C history, f ive side eff ects reported across 13 vaccine doses in 10 children with severe COVID-19 history, and 24 side eff ects reported across 89 vaccine doses in 40 control children (Table 1). The number of children who described at least one side eff ect after any vaccination dose was 18 (62.1%) for children with MIS-C history, 3 (30%) for children with severe COVID-19 history,and 16 (40%) for control children. The systemic reactions to total side eff ects ratios were 54.7%, 33.3%, and 33.3%in children with MIS-C history, severe COVID-19 history,and controls, respectively. The diff erence in systemic reaction rate between children with MIS-C history and control children was not statistically signif icant (P= 0.074). The most common vaccine-associated systemic side eff ects were fatigue (9.4%) and fever (9.4%) in children with MIS-C history, similar to the controls. The median duration between the f irst dose and our call was 119 days (5—206 days), and the maximum follow-up was 206 days. No severe systemic side eff ects were reported by any of the children, and no myocarditis or pericarditis was reported by vaccine recipients. The most common local side eff ect was injection site pain, reported by 4 (80%) of children with severe COVID-19 history and 16 (66.6%) of control children, similar to the 26 (40.6%) of children with MIS-C history (Supplementary Fig. 1).

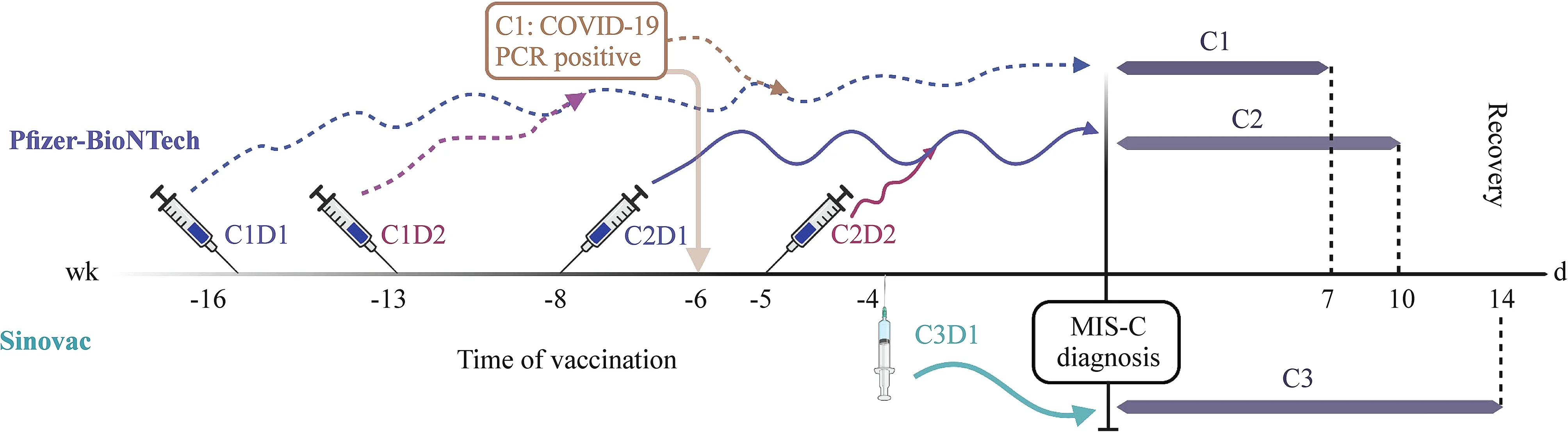

Two (3.1%) male children with MIS-C history had chest pain after the f irst dose of the Pf izer-BioNTech vaccine. The f irst child had chest pain that lasted two days within one month of vaccination. Myocarditis was ruled out because he had normal cardiac enzymes, electrocardiography, and echocardiography. He has not yet received the second vaccine dose. The second child had chest pain two days after the vaccination and resolved within three days without treatment at any health care facility. He received the second dose of the Pf izer-BioNTech vaccine without any side eff ects. In two children with MIS-C history, chest pain was observed 2—30 days after vaccination with the Pf izer-BioNTech vaccine, representing the longest duration observed between vaccination and the appearance of side eff ects. The median duration of side eff ects was one day (1—28 days) among children with MIS-C history, three days (1—3 days) among children with severe COVID-19 history, and one day (1—3 days)among control children. The longest-lasting vaccine-associated side eff ect was axillary lymphadenopathy, which lasted for 28 days. Three children were vaccinated before MIS-C diagnosis in our cohort (Fig. 2). All three children were discharged with no complications.

Fig. 1 The number of children included in this study. COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, MIS-C multisystem inf lammatory syndrome in children, CDC US Center for Disease Control, WHO World Health Organization

Table 1 Data of vaccinated children after MIS-C and severe COVID-19 diagnosis and control cases

The most common factor aff ecting the vaccination decision was infection or reinfection anxiety in the family, aff ecting 21 (72.4%) of children with MIS-C history, 8 (80%) of children with severe COVID-19 history, and 40 (100%) of control children. Other factors aff ecting vaccination decision-making for parents with children with MIS-C history were friends (13.8%), social media (6.9%), school (3.4%),and doctors (3.4%). Moreover, social media (10%) and doctors (10%) were the key factors aff ecting vaccination decisions for children with severe COVID-19 history.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the f irst study to evaluate the adverse eff ects of COVID-19 vaccination in children with a history of MIS-C and the factors inf luencing vaccination decisions. In this study, while most participating centers did not directly recommend COVID-19 vaccination for children with a history of MIS-C, 29.2% of children were vaccinated with any COVID-19 vaccine without serious adverse events. Therefore, our results indicate that the COVID-19 vaccines manufactured by Pf izer-BioNTech and Sinovac are well-tolerated in children 12—18 years old with MIS-C diagnoses. However, the number of vaccinated children included in this study is small, particularly for the Sinovac vaccine. Our f indings are consistent with an international electronic survey on vaccination in children with MIS-C history that found COVID-19 vaccines safe and well tolerated [ 6]. Nevertheless, larger epidemiological studies with clinical follow-up are required to evaluate further the safety of COVID-19 vaccines in children with MIS-C history.

Systemic and local reactions are commonly reported in adolescents after vaccination with coronavirus vaccines[ 7, 8]. In this study, both systemic and local reactions were observed in children with MIS-C and severe COVID-19 history and in controls. However, there were no hospitalizations due to severe adverse events. No statistically signif icant difference in systemic reaction rate was found between children with a history of MIS-C and controls. Nevertheless, more than half of children with the history of MIS-C reported at least one systemic or local side eff ect after vaccination.Injection site pain was the most frequently reported side eff ect, followed by fatigue, fever, headache, and arthralgia.These f indings are consistent with a review of vaccine-safety data that found injection site pain, fatigue, headache, and myalgia to be the most commonly reported reactions in adolescents older than 12 years [ 7].

According to the CDC, one of the most commonly reported side eff ects following COVID vaccination was chest pain, a precursor symptom for myocarditis. Myocarditis is rare but has occurred in some mRNA-based COVID-19-vaccinated individuals, particularly those aged 12 years and older. Furthermore, myocarditis cases have been reported predominantly in males aged 12—29 years within the f irst week after receiving their second vaccine dose [ 1].Two children in our study experienced chest pain, but neither was diagnosed with myocarditis. Additionally, it is important to note that myocarditis/pericarditis risk associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection is greater than that of mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination in adolescents [ 1].

Fig. 2 Vaccine types and the timing of COVID-19 vaccination and MIS-C diagnosis in three children who were vaccinated prior to MIS-C diagnosis. PCR polymerase chain reaction, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, MIS-C multisystem inf lammatory syndrome in children,C1D1 case 1 dose 1, C1D2 case 1 dose 2, C2D1 case 2 dose 1, C2D2 case 2 dose 2, C3D1 case 3 dose 1 (the f igure was created using Biorender.com)

The basis of vaccination decisions, which could substantially increase population immunity in the future, is a matter of curiosity. One of the most striking f indings of our study is that most parents decided to vaccinate their children based on concerns about COVID-19 reinfection in the context of the ongoing pandemic regardless of their doctor’s recommendation. Among the seven tertiary-care pediatric centers participating in this study, only 14.2% of their doctors recommended COVID-19 vaccination of children with a history of MIS-C. These data highlight how indecisive physicians dealing with MIS-C can be regarding the vaccination of their patients. Moreover, family anxiety was a driving force behind the vaccination of children with a history of MIS-C,complicating vaccination recommendations for pediatricians and potentially important for vaccination decision-making in the broader infectious disease f ield. Three of our children were vaccinated before their MIS-C or COVID-19 diagnosis.One child had diabetes mellitus as an underlying disease that may decrease vaccine eff ectiveness [ 9]. Similarly, MIS-C cases with vaccination history before diagnosis are rarely reported [ 10— 15], leading to physician concerns regarding vaccine eff ectiveness or potential COVID-19 vaccine-associated MIS-C.

Following the identif ication of MIS-C, MIS in adults and hyperinf lammation after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination have emerged as new conditions that challenge our understanding of the nature of this inf lammatory condition that has high mortality and appears to be associated with SARS-CoV-2 and its antigens. It remains unclear how SARS-CoV-2 vaccines cause the hyperinf lammatory response. Buchhorn et al.compared functional autoantibody levels with G-proteincoupled receptors among four children with MIS-C diagnoses following COVID-19 and two children with MIS-C after vaccination with the Pf izer-BioNTech vaccine, concluding that it ref lects the eff ects of the spike protein on multiple autoantibody pathways [ 13]. However, further evidence is required to conf irm this hypothesis.

The CDC has reported recently that the estimated eff ectiveness of vaccines against MIS-C was 91%. Receiving two doses of the Pf izer-BioNTech vaccine eff ectively prevented MIS-C in children aged 12—18 years [ 1]. Therefore, clinicians should consider MIS-C diagnosis even in vaccinated children, and vaccination is likely eff ective in preventing severe COVID-19-related complications in children, including MIS-C. In this study the vaccination rate was lower in children with a history of severe COVID-19 than in children with a history of MIS-C or control children. However, no clear data about the vaccination rate and basis of vaccination decisions in children with severe COVID-19 history have been reported. Our study included a small number of children in that category. However, additional robust studies with larger cohorts are required to determine vaccination rate, side eff ects, and eff ectiveness and to identify factors behind vaccine hesitancy.

In conclusion, our results indicate that it seems as if COVID-19 vaccines are well tolerated in children aged 12—18 years with MIS-C diagnoses. However, additional studies with larger cohorts and diff erent COVID-19 vaccines are required to evaluate their eff ects on children with MIS-C history and the role of COVID-19 vaccination in preventing MIS-C.

Supplementary InformationThe online version contains supplementary material available at https:// doi. org/ 10. 1007/ s12519- 022- 00604-7.

Author contributionsKA contributed to conceptualization, methodology, and software. KO, OOD, and DDG contributed to data curation.SA, EC, MYC, MDK, GA, FDA, and BCCY contributed to data curation and original draft preparation. EK, SC, ME, ID, ABC, and MC contributed to supervision. YO contributed to reviewing and editing.All the authors approved the f inal version of the manuscript.

FundingNo funding was secured for this study.

Data availability The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approvalThis study was approved by Hacettepe University Ethics Committee (2022/03-74).

Conflict of interestThe authors have indicated they have no potential conf licts of interest to disclose.

杂志排行

World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Single ventricle: amphibians and human beings

- Clinical diff erences among racially diverse children with celiac disease

- Effi cacy of live attenuated vaccines after two doses of intravenous immunoglobulin for Kawasaki disease

- Associations between body mass index in diff erent childhood age periods and hyperuricemia in young adulthood: the China Health and Nutrition Survey cohort study

- Music therapy and pediatric palliative care: songwriting with children in the end-of-life

- Secondary genomic f indings in the 2020 China Neonatal Genomes Project participants