Enduring legacy of coal mining on the fungal community in a High Arctic soil after five decades

2022-11-01DorsafKERFAHIKevinNEWSHAMKeDONGHokyungSONGMarkTIBBETTandJonathanADAMS

Dorsaf KERFAHIKevin K.NEWSHAMKe DONGHokyung SONGMark TIBBETT and Jonathan M.ADAMS

1School of Natural Sciences,Department of Biological Sciences,Keimyung University,Daegu 42601(Republic of Korea)

2NERC British Antarctic Survey,MadingleyRoad,Cambridge CB3 0ET(UK)

3Department of Life Science,Kyonggi University,Suwon-si 16227(Republic of Korea)

4School of Earth and Environmental Sciences,The Universityof Manchester,Manchester M13 9PL(UK)

5Department of Sustainable Land Management&Soil Research Center,School of Agriculture,Policyand Development,Universityof Reading,Reading RG6 6AR(UK)

6School of Geographic and Oceanographic Sciences,Nanjing University,Nanjing 210008(China)

ABSTRACT Mineral extraction is known to affect soil fungi in polar environments,but it is unknown how long these effects persist.Here,by amplifying the internal transcribed spacer regions of rRNA genes in soil fungi,we compared soil fungal community in intact natural tundra with that in a nearby former coal mining area,abandoned 52 years previously,on Svalbard in the High Arctic.Compared with those in intact tundra,soils in the former mining area were more acidic and had lower plant coverage.Despite of similar diversity in the two areas,the fungal community was dominated by Basidiomycota in the intact tundra,but by Ascomycota in the former mining area.Ectomycorrhizal genera formed a major part of the tundra community,but were notably less abundant in the mining area.The principal variation among samples was soil pH.Surprisingly,network connectivity analysis indicated that the fungal community in the former mining area had greater network connectivity than that in the tundra area.Overall,the ecosystem in the former mining area has made only limited recovery towards the natural tundra state even after more than five decades.It is unclear whether the recovery of the fungal community is limited more by the low primary productivity,slow migration of fungi and plants,or slow changes in soil parameters.Our findings emphasize the susceptibility of polar ecosystems to disturbance,given their particularly slow recovery back towards the natural state.

KeyWords: abandoned mining site,ectomycorrhizal fungi,intact tundra,mine tailings,mineral extraction,polar ecosystem recovery

INTRODUCTION

Mineral extraction,particularly coal mining,has been practiced for more than a century on Svalbard(Hoel,1925;Miles and Wright,1978),an archipelago in the High Arctic located at 74–81°N.Coal mining operations commenced at several different locations on Spitsbergen,the largest island in the archipelago,in the early 1900s(Hisdal,1998;Dowdallet al.,2004),and the last coal mining activity at Ny-Ålesund,on which we report here, ended in 1962, when a major accident forced the closure of the mine.Mining operations have had substantial effects on the terrestrial habitats of Svalbard,many of which are still evident to this day.One of the main effects of coal mining regolith on soils is a sharp decline in pH, caused by the high sulfur content of coal spoil, which leads to sulfuric acid production. Soil pH in the vicinity of spoil heaps close to Longyearbyen on Svalbard can reach as low as 2.9(Askaeret al.,2008),which causes the release of metals such as nickel,zinc,and lead in runoff,known as acid mine drainage(Krajcarováet al.,2016;Kłoset al.,2017),the accumulation of cadmium(Cd)and molybdenum(Mo)in soils(Krajcarováet al.,2016),and subsequent damage to vegetation(Noll,2003).

However, the impacts of coal mining on soil fungal community have seldom been studied in polar environments(Mundraet al.,2016).This is a significant gap in knowledge,since fungi play pivotal roles in all terrestrial ecosystems as decomposers of organic matter and as partners in symbioses(Tedersooet al.,2014;Knacket al.,2015;Dighton,2016),notably the ectomycorrhizal(EcM)symbiosis,which helps plants to acquire growth-limiting nutrients from soils(Smith and Read,2010).

In this study,we investigated the long-term(ca.50 years)legacy of coal mining activity on Svalbard.We compared the soil fungal community in a spoil heap area at an abandoned coal mining site with that in a nearby area which,according to local records and habitat surveys(Gawor and Dolnicki,2011),is intact natural tundra.The principal question motivating our study was:to what extent is the legacy of past coal mining activity still present in the fungal community within the affected area,compared with the natural undisturbed tundra?We hypothesized that,as suggested by their generally sparse vegetation with low frequencies of EcM-forming dwarf prostrate shrubs such asSalixpolaris(Väreet al.,1992),the abandoned spoil heaps would have lower fungal diversity and a simpler,less integrated(indicated by lower connectivity)fungal community compared with the natural tundra,with a lower relative abundance of EcM fungi.Such a finding would emphasize that, based on the vegetation composition and cover,soil functionality is still far removed from the natural tundra,indicating the long persistence of an anthropogenic legacy in this environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site description

Soil samples were taken in July 2014 at sites near the Dasan Base at Ny-Ålesund on the Brøgger Peninsula,situated on the west coast of Spitsbergen(Fig.1).The mean summer air temperature at Ny-Ålesund isca.4°C,with a mean air temperature of-12°C during winter(Førlandet al.,2011).The growing season for plants usually starts in mid-June and ends in late August.The mean annual precipitation is 330 mm(Førlandet al.,2011),mostly falling as snow outside the brief growing season.With a mean annual temperature ofca.-5°C,much of Svalbard is underlain by permafrost.

Fig.1 Satellite image of Ny-Ålesund,Svalbard,the High Arctic(a)and ground-level views of the two soil sampling sites near the Dasan Base in Ny-Ålesund, i.e., the undisturbed natural tundra site (b) and the former mining site(c).Sources:Environmental Systems Research Institute(ESRI)and the Geographic Information System(GIS)User Community.

The soils of the Brøgger Peninsula are mostly poorly developed Lithic Haplorthels,and the bedrocks are dominated by Upper Carboniferous and Permian rocks with quartzite and interlayered carbonates (Wojciket al., 2019). Accordingly,soil pH in the intact areas is weakly acidic to alkaline.At 13 undisturbed sites sampled along the peninsula, soil pH ranged between 6and 8.5, with a mean value of 7.5(Zhanget al.,2016).The natural vegetation of the peninsula is a mixture of grasses,mosses,lichens,dwarf shrubs,and cushion plants(Bliss and Matveyeva,1992;Coulsonet al.,1993;Cooper,2011),forming a patchy mosaic of various habitat types(Jónsdóttir,2005;Coulsonet al.,2015).

The history of the Svalbard archipelago is well documented,including the history of the research base and airstrip.Settlement on Svalbard has always been limited, with no established population in the area before the coal mine was founded(Miles and Wright,1978).Some old roads remain but are covered by vegetation.Grazing from introduced reindeer,which are present everywhere on Svalbard,occurs at low intensities, but on the coastal plain tundra area adjacent to the mine, there are no obvious trampling effects from humans or animals except for limited trackways.The boundaries of the mining area are well marked by the topographical features of spoil heaps,concrete,and a range of other artifacts such as wooden debris.These are absent from the adjacent flat coastal plain tundra.It is clear that,apart from clearly defined old roads and trackways,which we avoided sampling,the adjacent tundra is essentially in a near-natural state.

Sampling methods,DNA extraction,and soil analysis

A total of 11 soil samples were collected from an area of the undisturbed natural tundra (Fig. 1a, b). More than 90%of the ground in this area was covered by plants(e.g.,mosses).As is typical for undisturbed plant community in low-lying areas on the Brøgger Peninsula(Kernet al.,2019),the natural tundra vegetation was dominated by the dwarf shrubS.polaris(Fig.S1,see Supplementary Material for Fig.S1).Another EcM species,the forbBistorta vivipara(Väreet al.,1992;Mundraet al.,2016),occurred in the undisturbed tundra along withSaxifraga oppositifolia,mosses(DicranumandPohliaspp.),lichens,and occasionalSilene acaulis.The entire sampling area measured approximately 70 m×70 m and was centered at 78°55.242′N,11°56.809′E.Within this area,11 quadrats of 1 m2were placed at least 20 m apart,and five soil cores 10 cm in diameter and 5 cm in depth were collected from each of the four corners and the center of each quadrat,after gently removing any surface mosses and rocks.These five subsamples from each quadrat were then pooled and gently mixed,generating 11 composite soil samples,one per quadrat.

Soil samples were collected from spoil heaps and the areas between heaps at the former mining site,which is one of the two main mines in Ny-Ålesund(Fig.1a,c).The spoil heaps were covered with fragments of coal shale,scattered lumps of coal,a thick layer of coal dust,and wooden and metal debris(Fig.1c).The vegetation cover(<50%)was lower than that in the tundra area(Fig.S1)and consisted mainly of mosses(typicallySanionia uncinata),with scattered patches of lichens,S.acaulis,Dryas octopetala,andFestucaspp.,and occasional EcM-formingS.polarisandB.vivipara.The sampling area was approximately 70 m×70 m and centered at 78°54.716′N,11°57.569′E.Ten composite soil samples were collected from 10 quadrats(1 m2)at least 20 m apart within this area in the same way as described above.

The 21 composite soil samples were transported to the laboratory in Ny-Ålesund, where they were air-dried and DNA was extracted from 0.3 g subsamples using the Mo-Bio Power Soil DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories,USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was stored at-80°C and then sent frozen with dry ice for sequencing at Dalhousie University,Canada,using the paired-end (2× 300 bp) Illumina MiSeq platform(www.cgeb-imr.ca).Polymerase chain reaction(PCR)primers targeting the fungal internal transcribed spacer(ITS)region of rRNA genes(i.e.,ITS2,averageca.350 bp)were ITS86F and ITS4R(Vancov and Keen,2009).Soil pH was measured by adding approximately the same volume of deionized water toca. 4 g (fresh weight) soil to generate slurries(Gavlaket al.,2003;Miller and Kissel,2010)and recording the pH after 10 min using a glass electrode(pH 21,Hanna Instruments,UK).Total nitrogen and carbon concentrations were measured by combustion using dried soil samples at the National Instrumentation Center for Environmental Management, South Korea, based on the standard Soil Science Society of America protocol.Briefly,soil samples were weighed into small foil capsules and combusted in an automated LECO CHN 600 analyzer(LECO Corp.,USA).The released carbon dioxide(CO2)and dinitrogen(N2)were quantified by gas chromatography(Sparkset al.,2020).

Sequence processing

The sequence data generated from the Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform were processed using Mothur(Schlosset al.,2009).Sequences with ambiguous bases,with more than eight homopolymers, and<200 bp were removed using the screen.seqs command in Mothur.Putative chimeric sequences were detected and removed using the Chimera Uchime algorithm contained in Mothur inde novomode(Edgaret al.,2011),which first splits sequences into groups and then checks each sequence within a group using the more abundant groups as a reference.Rare sequences(<10 reads)were removed to avoid the risk of including spurious reads generated by sequencing errors (Huseet al., 2010).Operational taxonomic units(OTUs)were assigned using the QIIME implementation of UCLUST45,with a threshold of 97%pairwise identity.Taxonomic classification of each quality sequence was performed against the UNITE version 6.0 database(Kõljalget al.,2013),with the exception that members of Zygomycota were assigned to Mucoromycotina(Hibbettet al.,2007),using the classify command in Mothur at a cutoffof 80%with 1 000 iterations.The MiSeq sequence data used in this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information(NCBI)Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA561666.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed on a standardized subsample of 4 372 reads per sample using the sub.sample command (http://www.mothur.org/wiki/Sub.sample) in Mothur.Diversity indices such as Shannon index,Simpson index,and OTU richness were calculated using the Mothur platform(Schlosset al.,2009).To test whether the diversity indices and relative abundance of the most frequent fungal phyla differed significantly between the former mining and tundra sites, we usedt-test for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normal data in the R software package 2.15.2.Bray-Curtis distance was calculated to analyze fungal community similarity.To reduce the contribution of highly abundant OTUs in relation to less abundant ones in the calculation of the Bray-Curtis measure, abundance data of OTUs were square-root transformed,and the pairwise differences in fungal community composition were calculated by analysis of similarity(ANOSIM)in relation to Bray-Curtis distance.We performed regression analysis using linear functions in SigmaPlot to test whether fungal alpha-diversity indices(OTU richness,Shannon index,etc.)were correlated with soil parameters.Fungal functional guilds were assigned using FUNGuild(Nguyenet al.,2016).We only accepted guild assignments for which the confidence ranking was “highly probable”. Assignments were also manually checked to determine their accuracy.

RESULTS

Edaphic factors

As anticipated, soil pH was significantly lower (P=0.002,W=11)in the former mining area,with mean pH values of 4.8 (ranging 2.3–6.8) and 7.1 (ranging 6.5–8.2)for soils sampled from the mining and intact tundra areas,respectively(Fig.S2,see Supplementary Material for Fig.S2).Soil C and N concentrations did not differ between the two areas(Fig.S2).

Soil fungal communitydiversityand composition

After quality checking and trimming processes,we obtained a total of 91 812 quality fungal sequences from the 21 soil samples,which were classified into 2 005 OTUs at the 97% similarity level. To correct for differences in the numbers of reads,all samples were subsampled to the level of the smallest number of reads found in any one sample(4 372). Alpha diversity, calculated using OTU richness and diversity indices,did not show any significant variation(P≥0.07,W >41 for OTU richness and Simpson and Chao indices;P= 0.14,t=-1.54 for Shannon index)between the tundra and former mining areas(Fig.S3,see Supplementary Material for Fig.S3).

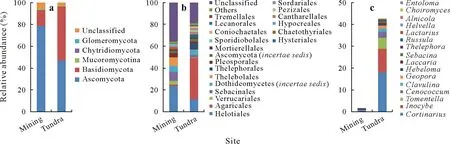

Five fungal phyla and subphyla were present in the soils.Ascomycota was the most abundant phylum,representing about 63%of all detected fungal reads,followed by Basidiomycota(32%)and the subphylum Mucoromycotina(1.5%),with Chytridiomycota and Glomeromycota accounting for<1%of the total reads(Fig.2a).Less than 4%of the total reads were unclassified.The relative abundances of the different phyla and subphyla varied significantly between the former mining and tundra areas,except for Mucoromycotina(P=0.083,W=51.5).The relative abundance of Ascomycota was significantly higher (P <0.001,t= 4.37, degree of freedom (df) = 14.96) in the former mining area (78%)than in the natural tundra(47%).Basidiomycota displayed the opposite pattern (P <0.001,W= 10), with relative abundances of 15%and 49%in the former mining and tundra areas, respectively. Compared with the above three phyla and subphyla,Chytridiomycota and Glomeromycota were present at lower frequencies in the former mining (P=0.004,W=88)and tundra areas(P=0.034,W=60.5).

There were significant differences between the two areas in the relative abundances of nine frequently detected orders(Table SI,see Supplementary Material for Table SI).Among the most abundant orders(relative abundance>1%),only Agaricales differed significantly (P <0.001,W= 0) in frequency between the two areas. This order was more abundant in the tundra area (37.5%) than in the former mining area(1.5%)(Fig.2b).Helotiales was the second most abundant order,representing 17%on average of total fungal reads,but did not differ(P=0.25,W=72)in frequency between the coal mining (23%) and tundra areas (11%).The order Sebacinales had an average relative abundance of 5.6% and did not show any variation between the two sites(P=0.41,W=67).Dothideomycetes,Thelebolales,and Pleosporales had relative abundances<5% and did not vary between the two sites,either(P=0.19,W=36 for Dothideomycetes;P=0.35,W=67 for Thelebolales;P=0.83,W=51.5 for Pleosporales).

He arrived home on February, 3, 1981.Three days later, he arranged to see Diana at Windsor Castle. Late that evening, while Prince Charles was showing Diana the nursery, he asked her to marry him.

A total of 24 139 sequences belonged to known groups of EcM fungi and accounted for approximately 25% of the total fungal sequence reads.The relative abundance of EcM fungi was significantly higher(P <0.001,W=0)at the tundra site(43%)than at the former mining site(2%),(Fig.2c).We identified 16EcM genera in the tundra area,withCortinariusbeing the dominant genus(18%),followed byInocybe,Tomentella,Cenococcum, andClavulina. In contrast,only eight genera were found in the former mining area.A heat map illustrating the most abundant EcM OTUs in the soils showed that the relative abundances of the generaCortinariusandTomentellawere significantly higher(P <0.001,W=0.2 andP <0.001,W=0,respectively)in the tundra than in the mining areas (Fig. 3, Table SII,see Supplementary Material for Table SII). The generaCenococcum,Clavulina,andSebacinawere only detected in the tundra area (P≤0.003,W= 5–20). In contrast,the relative abundances ofRhizoscyphus,Rhodotorula,andCladophialophorawere significantly lower (P≤0.010,W=91–98)in the tundra than in the former mining areas.

The non-metric multidimensional scaling(NMDS)plot of pairwise Bray-Curtis dissimilarities revealed that the soils from the two sites had distinct(ANOSIM:R=0.68,P=0.001) fungal communities that formed separate clusters(Fig. 4). The environmental fitting analysis indicated that only pH was a strong structuring factor for fungal community composition(r2=0.534,P=0.001).

Fig.2 Relative abundances of fungal phyla(a),fungal orders(b),and ectomycorrhizal fungi(c)detected at the undisturbed natural tundra site and the former coal mining site near the Dasan Base in Ny-Ålesund,Svalbard,the High Arctic.

Fig.3 Heat map of the 30 most abundant fungal operational taxonomic units(OTUs)recorded in the 11 composite soil samples from the undisturbed natural tundra site(Tundra1–Tundra11)and the 10 composite soil samples from the former coal mining site(Mining1–Mining10)near the Dasan Base in Ny-Ålesund,Svalbard,the High Arctic.A darker blue color represents a higher abundance.

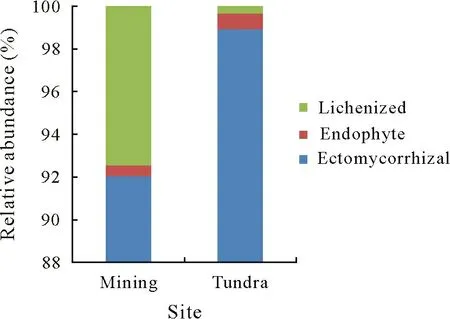

Taxonomic functional analysis using FUNGuild showed that 18% on average of the total OTUs were assigned to the “highly probable” confidence ranking, with 25% for the tundra site and 10% for the mining site. All of these fungal taxa belonged to the symbiotroph category.Fungal OTUs were classified into three fungal guilds,i.e., EcM,endophyte, and lichenized (Fig. 5). The tundra site had a significantly higher (P= 0.002,t=-3.74, df = 13.76)relative abundance of EcM fungi than the former mining site.However,lichenized fungi were significantly more abundant(P=0.01,W=89.5)at the mining site than at the tundra site.Endophytic fungi did not differ(P=0.60,W=47.5)in relative abundance between the two sites.

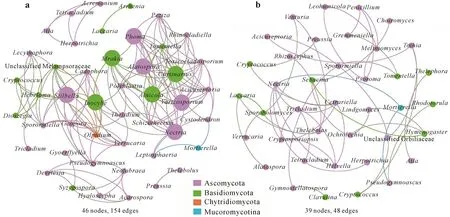

Correlation-based network analysis was conducted to study the connectedness between different fungal genera at the two sites(Fig.6). The connectivity analysis, which was based on significant positive correlations (r >0.90,P <0.05),showed that the mining site(46nodes and 154 edges) had a higher number of positive correlations than the natural tundra site(39 nodes and 48 edges).The fungal taxa showing the highest number of positive correlations with other taxonomic groups and functional groups belonged toInocybe,Geopora,Thelidium,Verrucaria, andPhomaat the former mining site andGremmeniella,Clavulina,Penicillium,andThelephoraat the tundra site.

DISCUSSION

Fig.4 Non-metric multidimensional scaling(NMDS)ordination based on Bray-Curtis distance showing the clustering of fungal communities in relation to soil pH at the former coal mining site and the undisturbed natural tundra site near the Dasan Base in Ny-Ålesund,Svalbard,the High Arctic.

The observations reported here showed a clear difference in soil fungal community composition and diversity between the intact tundra and former mining areas on Svalbard,supporting our hypothesis and indicating that a legacy of coal mining activity has persisted in this High Arctic environment for more than half a century.The most striking differences between the two habitat types were the abundance and diversity of EcM fungi.These taxa,which are chiefly Basidiomycetes in the order Agaricales(Smith and Read,2010),were much more abundant and diverse in the intact tundra than in the former mining area(Fig.2c).

Fig.5 Relative abundances of fungal functional groups(trophic modes)at the former coal mining site and the undisturbed natural tundra site near the Dasan Base in Ny-Ålesund,Svalbard,the High Arctic.

The reduced incidence of EcM host plants is probably a significant factor in explaining the lower abundance and diversity of EcM taxa in the former mining area. In the mining area, coverage by the EcM host plant speciesS.polarisandB. viviparawas lower than that in the intact tundra. Both of these higher plant species are routinely colonized by EcM fungi on Svalbard, often by the same EcM genera that were recorded in the soils studied here,i.e.,Cortinarius,Inocybe,andLaccaria(Väreet al.,1992;Mundraet al.,2016),which at least in part explains the lower abundances of these genera in the mining soils.However,there were substantial differences in soil edaphic factors between the intact tundra and former mining areas,notably pH,with mean pH values of 7.1 and 4.8 in the two areas,respectively. Given that soil pH has substantial effects on the taxa of soil fungi,including EcM taxa(Tedersooet al.,2014; Timlinget al., 2014; Newshamet al., 2017), it is likely that the observed differences in the composition of EcM community between the former mining and tundra sites(Fig.2c)were at least partly associated with the lower soil pH in the former mining area.

Fig.6 Co-occurrence network analyses of fungal genera at the former coal mining site(a)and the undisturbed natural tundra site(b)near the Dasan Base in Ny-Ålesund,Svalbard,the High Arctic.The edges stand for significant correlations(Spearman’s ρ >0.9,P <0.01).The size of each node is proportional to the number of connections.Different colors represent different phyla.

The accumulation of heavy metals such as copper(Cu)and Mo in the former mining soil(Krajcarováet al.,2016;Kłoset al.,2017)might have affected the fungal community composition. A previous study found thatLaccariaandHebeloma,which synthesize metallothioneins in response to Cu and Cd exposure(Rameshet al.,2009;Reddyet al.,2014), are frequent EcM symbionts ofB. viviparagrowing in mine tailings on Svalbard(Mundraet al.,2016).In addition,the slow dispersal of certain key EcM species or other keystone fungal species involved in nutrient cycling or acquisition might have prevent the recovery of vegetation in the mining area.Previous studies on post-mining areas in temperate habitats reported slow recovery of EcM species.This may hinder soil development and may even necessitate the inoculation of EcM propagules into soil in order for woody plants to become established(Reddell and Milnes,1992; Haselwandter and Bowen, 1996; Glenet al., 2008;Spainet al.,2015).While this mechanism might in part be responsible for the lack of recovery at the former mining site on Svalbard,the dispersal of EcM spores,across both the Arctic and temperate regions,is widespread and takes place over great distances(Gemlet al.,2012).Thus,it is likely that differences in EcM host coverage and edaphic factors were primarily responsible for the lower diversity and reduced frequency of EcM fungi at the former mining site here.

Previous studies on temperate habitats similarly found detrimental effects of coal mining activity on soil fungal community, but with faster recovery. In a recent study at rehabilitated mine sites in eastern Australia,although there was no significant change in the relative abundance of EcM fungi over time,the richness of EcM fungi in soil increased over the 3–23 years after mining had ceased(Ngugiet al.,2020). A study in the Czech Republic also found significant development of plants and soil fungal community on a chronosequence of coal mining spoil heaps over 54 years(Harantováet al., 2017). The authors reported that Ascomycetes such asPseudogymnoascus,Cladosporium,andTrichodermawere frequent in the soils up to 13 years post mining, consistent with the results of the present study.However, in contrast to our observations, EcM fungi in the Czech study, includingTomentella,Cortinarius, andRussula,became frequent in the spoil heaps after 21 years,corresponding with increased cover by the gymnospermsPinus sylvestrisandPicea abies(Harantováet al., 2017).The much longer recovery time of>50 years reported here suggests that the more extreme environmental conditions on Svalbard,where soil temperatures down to 10-cm depth remain below freezing point for 8–10 months each year(Tibbett and Cairney,2007;Conveyet al.,2018),probably inhibit recovery from mining activity(Coulsonet al.,1995).

With approximately twice as many EcM genera, the EcM community in the undisturbed natural tundra was more diverse than that in the mining area.CortinariusandTomentellawere frequent at the tundra site. However, the diversity of the total fungal community did not differ between the two areas.A previous study in a temperate environment showed reductions in fungal species richness(Chao 1)due to coal mining activity,with recovery spanning 23 years(Ngugiet al.,2020),but other studies on soil microbial community in temperate habitats found no or apparent positive effects of coal mining activity on Chao 1 diversity(Ponceletet al.,2014;Harantováet al.,2017).These previous data and the data reported here suggest that in some instances,the overall diversity of soil microbial community may be unaffected by mining activities, probably owing to increases in the frequencies of stress-tolerant microbes such asBeauveriaandPenicilliumin soils following disturbance(Arnebrantet al.,1987;Harantováet al.,2017;Ngugiet al.,2020).

We hypothesized that fungal community connectivity would be lower in the former coal mining area. In fact,the results showed the opposite pattern,where the miningassociated site had higher connectivity than the tundra site.The implications of this for the resilience of the soil fungal community are unclear, but it contrasts with typical expectations that later successional communities are more connected.Morriënet al.(2017)found that on abandoned arable land,soil biological networks became more connected as succession proceeded,with enhanced efficiency of nutrient cycling, which can be explained by a change in the composition and/or activity of soil fungal community.Greater connectivity in an earlier successional or perturbed system suggests that the paradigm proposed by Morriënet al.(2017)may not be universally true.We similarly found greater fungal community connectivity in logged tropical forests and palm oil plantations than in primary forests(Tripathiet al.,2016),which also challenges the view that connectivity is usually greater in systems that have not been recently perturbed.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study shows a clear effect of former coal mining activity on the fungal community of a High Arctic soil more than five decades after mining activities ceased,emphasizing the slow rate of ecosystem recovery and succession in this polar environment.It is unclear to what extent the limited vegetation cover arises from the lack of development of soil fungal community and to what extent the lower vegetation cover itself limits the development of soil fungal community.It would be interesting to conduct experiments in which plant species, soil organic matter, nutrients, and fungal inoculum are introduced separately to disentangle cause and effect, with larger numbers of replicate samples allowing structural equation modelling analyses(Benschotenet al.,1997). The higher connectivity of soil fungal biota in the former mining area suggests that the paradigm that earlier successional systems develop greater connectivity may not apply universally.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material for this article can be found in the online version.

杂志排行

Pedosphere的其它文章

- Effects of silver nanoparticle size,concentration and coating on soil quality as indicated by arylsulfatase and sulfite oxidase activities

- Comparing the Soil Conservation Service model with new machine learning algorithms for predicting cumulative infiltration in semi-arid regions

- Time effects of rice straw and engineered bacteria on reduction of exogenous Cu mobility in three typical Chinese soils

- Carbon nanomaterial addition changes soil nematode community in a tall fescue mesocosm

- In situ stabilization of arsenic in soil with organoclay,organozeolite,birnessite,goethite and lanthanum-doped magnetic biochar

- Improvement of phosphorus uptake,phosphorus use efficiency,and grain yield of upland rice(Oryza sativa L.)in response to phosphate-solubilizing bacteria blended with phosphorus fertilizer