吴子熊:让玻璃艺术走向世界

2022-08-26包建永

文/包建永

只要一台砂轮机,吴子熊就能随心所欲地在玻璃杯上刻画和“写字”。With a grinding wheel, Wu Zixiong is able to carve and “write” on glass jars at will.

他的玻雕技艺,已炉火纯青。

飞轮转动,随手拿起一个玻璃杯,以轮为笔,一件玻雕艺术品,瞬间可就。花鸟虫鱼,栩栩如生;砂轮题字,笔走龙蛇。

看他表演玻雕技艺,是一种享受。

许多慕名而来的游客,就是为了一睹玻雕大师现场献技的风采。 “真快!”“真好!”这样的赞美,几乎每次展示都能听到。

赞美的背后,是中国工艺美术大师、浙江省非物质文化传承人吴子熊对玻雕艺术的不懈追求,以及对实现人生价值的无限渴望。

吴子熊与玻雕艺术打交道六十多年,虽然名满天下,但他从未改变工匠本色,一直自称“老工匠”。

在台州市民广场西侧,有幢二层楼的灰色建筑,这就是吴子熊玻璃艺术馆,每天游客骆驿不绝。艺术馆免费对外开放,每当有组团而来的游客,他常常亲自当导游,启动砂轮,为游客展示玻雕艺术的魅力。

其实在游客惊奇于吴子熊的玻璃艺术品时,人们更惊叹于他的传奇人生经历。他从一名小乞丐、搓澡工、车间工人,成长为享誉世界的工艺美术大师。他的玻雕作品,深受世界各国人民喜爱,先后收到三万余件外国友人的题词和签名。

找到一生的事业

1942年秋,吴子熊出生于台州仙居县田市吴桥村。他的祖父是清末秀才,曾行过医,教过书。父亲自幼跟随祖父读书习医。在他出生当晚,父亲梦见一只大黑熊窜进屋里,惊出一身冷汗;醒后不久,儿子出生。父亲给他取名“子熊”。

吴子熊在家排行老六,上有两个哥哥和3个姐姐。在他出生的时候,正值抗战相持阶段,吴家家境已经非常贫困。全家借住在村旁的尼姑庵里。

1946年初,母亲在贫寒交迫中,痛苦离世。1948年,父亲在海门(今属椒江)行医,他与10岁的姐姐少秋和8岁的哥哥和中相依为命,自力更生。半年后,他们才被接到海门,与父亲团聚。

在海门,吴子熊从三年级才开始插班上学。

然而,好景不长,父亲因病去世。为了生存,继母不得不改嫁。

小学毕业后,吴子熊深知继母不容易,他卖过大饼、馒头,做过乞丐,挨过打,受冻挨饿是生活常态。

后来,他渐渐长大。有一年夏天的黄昏,他百无聊赖地走在海门街上,内心烦躁至极。

不知不觉走到海门玻璃厂门口,一个穿着短裤的中年男子,站在阴凉处乘凉。

“同志,您这里需要学徒吗?”吴子熊大着胆子上去问。

“小鬼,你多大了?”是一个外地口音。

“16岁。”

“明天过来吧。”中年男子摸摸他的头说:“我们正好缺一个炉头送瓶人。”

真是“踏破铁鞋无觅处,得来全不费工夫”。

吴子熊的人生轨迹,就这样不经意间发生了改变。

他成了国营企业海门玻璃厂的工人。他的工作,是把炉台上一只只还在溶液中演变成型的各色玻璃器皿,用竹棒插入断口之中,以最快的速度,送到15米外的退火窑窑口。退火工人再用长铁叉接过器皿,送入烈火熊熊的退火窑内。

吴子熊平均每天要送500多个玻璃器皿,也就是在15米的距离内,来回走500多趟,相当于在高温的车间里快步走至少15公里的路程。

他珍惜这份工作,早上班,晚下班,埋头苦干,毫不抱怨。

后来,厂里决定在众多的徒工中选拔一个去研发新的花色品种,大家一致推荐了吴子熊。于是,他被调配给一个师傅当助手,做喷花。

1960年,他又被选中,派去旅大玻璃制品厂参观学习3个月。此次去学习的,还有全国各地玻璃厂派去的几十名技术人员。

在当时,旅大玻璃制品厂是中国玻璃行业的老大,技术上独领风骚。在陈列室里,各种颜色、各种造型的花瓶、花篮、顶灯,绚丽多彩,让人眼花缭乱。美丽的金鱼,开屏的孔雀,嬉水的游虾,仿佛是晶莹玉石上的天然之作。

吴子熊叹为观止。

和他一起来学习的同行都想学艺。但是,厂里只许参观,不传技术,也不许拍照。

“这么难得的机会,我一定要学到本领。”在吴子熊的请求下,他被分配到刻花车间参观。他用心默记车间师傅精湛的雕刻技巧,每一片花瓣,每一条枝丫,每一个连接图案,他都用笔画在手掌上;手上画满了,就借口上厕所,在厕所里迅速把图案分拆,画在香烟壳上。晚上回宿舍,再把香烟壳和手掌上的图案,重新组合起来,画在稿纸上。

师傅们技术捂得紧,他就用真心换真情。每天早上,他第一个到车间,帮助师傅把木桶里的水盛满,把车架擦干净。下班后,又抢着帮助执勤的师傅搞卫生。得知车间里有3位女师傅家里困难,他省下口粮,送给她们5斤、10斤的全国粮票。

日久见人心。师傅们终于松口了,把各自擅长的雕刻手法和技巧都传授给了他。不久后,组内拨出一架空置的砂轮机,让吴子熊等人轮流上岗练习技艺。有时候,师傅们有事或请假,也会让吴子熊代为磨刻。在此期间,他还跟随厂里的师傅,参与了北京人民大会堂的吸顶灯刻制。

晚上和周末的时间,吴子熊也不浪费,他去百货商店、博物馆、展览馆等场所参观,凡有玻璃器皿造型和雕刻图案,他都一一画下来。不到3个月时间,他已经摹画下了近千幅图案资料。

“玻雕艺术让人着迷,我决定为它奋斗终生。” 吴子熊雄心勃勃。

让观者惊为绝技

见过了大海,便不满足于在湖泊里遨游。

从旅大玻璃制品厂回来后,海门玻璃厂党支部研究决定,由吴子熊组建刻画车间,培养人才。

与旅大玻璃制品厂的刻画技术相比,海门玻璃厂的喷砂技术显得非常落后—经过喷砂的玻璃器皿,只留下砂痕,并没有其他图案。喷砂车间不但砂灰飞扬,环境恶劣,还有一定危险性。

吴子熊的首要任务,就是造一台砂轮刻画机。他尝试着改进工艺,试了几次,都失败了。

他四处寻访,找到一位叫邱兆法的老工人。邱师傅在上海中华玻璃厂工作过,曾亲见日本磨花玻璃技师的操作过程。回海门时,他向厂里的老师傅购买了一堆废弃的小砂轮。

“您的小砂轮能卖给我们吗?”

“不用买,我也为海门玻璃厂的发展尽一点力吧。”

在邱师傅的指导下,一台简易刻花机很快就做成了。全厂职工翘首以盼,等待试验成功。

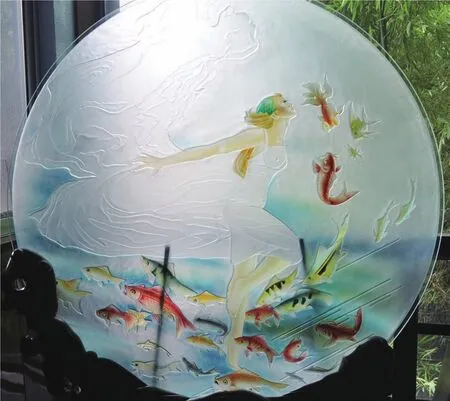

玻雕作品。A work of glass carving and sculpture.

吴子熊既激动,又忐忑。他坐下,开动电动机,小砂轮呼呼地转动起来。他紧握玻璃杯,在砂轮尖上轻轻一碰,划出一道白色弧线,正当他要雕刻花瓣时,“啪”的一声,杯子裂了。他拿起第二只杯子,又是“啪”的一声……连续试了5次,裂了5次。

工人们兴奋而来,一个个无声走开。

没有人比吴子熊更懊恼,但也没有人比吴子熊更坚持。

满足广大农村地区读者的阅读需求是新闻出版公共服务体系的重点之一。到2017年,我国已建成农家书屋60万个,覆盖了全国具备基本条件的行政村,建成数字农家书屋3.5万个,城乡阅报栏(屏)10万个,形成了形式多样、内容丰富的立体传播体系。

他不气馁,去请教车床师傅。车床磨刀师傅告诉他,砂轮转速快,冲力大,磨刀的力量也大;反之,磨刀的力量也小。“要磨出一把锋利的切割刀,砂轮转速很关键。不知道刻玻璃是否也是这个道理?”

一语点醒梦中人。吴子熊记得旅大玻璃制品厂的刻花机转速在400至600转/分钟,他跑回厂里测试,这台简易刻花机的转速居然达到了1000转/分钟以上。这么高的转速,玻璃岂有不破之理!

解决了症结所在,海门玻璃厂第一只刻花玻璃杯很快出品。技术就是红利。海门玻璃厂尝到了甜头,生意火了,刻花机也从1台迅速发展到80台,超过了旅大玻璃制品厂的规模。

吴子熊发现,旅大玻璃制品厂的雕刻师傅虽然技艺高超,但他们是按图刻样,一旦离开图纸,就束手无策,而画图的人,又不会雕刻。

他既会画图,又会操作,这是他的优势。

在海门玻璃厂第一台刻花机上操作尝试几个月后,吴子熊便不再满足于依样画葫芦。此时,他回望旅大玻璃制品厂,那些师傅的技艺不再可望而不可及;旅大玻璃制品厂陈列室里的展品,也不再那么神奇。

他决定创新,走出一条独一无二的玻雕之路。

他把中国传统水墨画艺术,融入到玻雕艺术之中。齐白石的“虾”,徐悲鸿的“奔马”,潘天寿的“苍鹰”,他都下过功夫仔细研究。

渐渐地,一只“活虾”,两只“活虾”……千百只“活虾”活跃于吴子熊的胸中。

从此,不论何时何地,只要一台砂轮机,一只玻璃杯,他就能在几十秒内刻出一只“活虾”来。

观者惊为绝技。

吴子熊变得“多愁善感”起来,世间太多的美好,让他留恋。“自然界中的一朵花,一只鸟,一次偶然的变化,一个微妙的象征,都会唤起我心头的美感。我要把这种美好的体验刻到玻璃作品之中,分享给更多的人。”

令世界为此赞叹

在特殊的十年里,海门玻璃厂业务量大减。这是吴子熊沉寂的十年,也是他技艺精进的十年。

这十年,他利用厂里的碎玻璃,在砂轮上反复练习,尝试各种雕刻手法,最终到达了只要脑中能想到、手下就能刻出的境界。

绘画的线条和构图、书法的走笔、音乐的节奏,都融合在他的玻雕艺术之中。他的作品,匠人按部就班的痕迹没有了,艺术的美感更浓郁了。

改革开放后,吴子熊迎来高光时刻。1978年,人民大会堂浙江厅整修,西厢壁上两盏玻璃雕花壁灯上的马蹄花图案,就是指定他雕刻完成的。之后,他在北京、香港、上海等地亮相,精湛的表演,令观者无不为之叫绝。

“吴子熊”的名字,不胫而走。国外的邀请函,也如雪花般飞来。从1986年起,他先后到访德国、荷兰、英国、澳大利亚、美国、日本、新加坡、意大利等国家,所到之处,现场献艺,无不惊艳四座。

离国越远,越牵挂祖国;出国越多,越觉得祖国可亲。

吴子熊在各国享受鲜花和掌声的同时,也深刻地感受到,许多外国人对中国缺乏基本的了解。1989年2月6日,是农历春节。他应邀在澳大利亚布里斯班市中心的“Myer”连锁商场表演。“Myer”是澳大利亚最大的百货商店集团。但是,当他走进豪华的商场时惊呆了。眼前,四根毛竹支起一个茅棚,茅棚边一把竹梯、一盆树景、四只箩筐—一幅原始的“中国家居图”,与周围环境极不相称。

“中国不是这样的,我不能在茅棚下工作。”吴子熊说。

在他的要求下,组办方另设工作台,重新布置现场。

他的表演一如既往的精彩。他在日记中写道,看着自己的表演和玻雕作品在异国他乡深受欢迎,“一股民族自豪感在胸中洋溢”。

吴子熊以玻雕为媒,自觉担负起文化使者的角色,积极走出去,让世界了解中国。一件件玻雕作品,成了他与数以万计的陌生人建立友谊的纽带。至今,他共收到外国友人题词、签名三万余件,其中不乏各国领导人和文化名人。

2004年5月,位于台州中心大道东侧的吴子熊玻璃艺术馆落成。该馆为国家3A级旅游景区,免费对外开放。

以艺术馆为阵地,立足台州,传播文化。吴子熊的人生,又翻开了新的一页。

正像他在玻雕作品《生命的力量》里表现的那样—生命是顽强的,他所经历的种种苦难和失败,到最后,都成了他不断努力、走向成功的宝贵经验和财富。

“马的一生,是奔跑一生,死时都是保持站立的姿势。我要像马一样,在绚烂的有情世界里,在透明的玻璃世界里,接受考验,奔跑不止。”吴子熊说。

吴子熊玻璃艺术馆第二代传人、中国玻璃艺术大师吴刚和徒弟孙亮的玻雕作品《中国加油—众志成城战疫情》。Go China — Stand United to Fight the Epidemic, a work of glass carving and sculpture by Wu Gang, a second-generation craftsman of the Wu Zixiong Glass Art Gallery and a Chinese master of glass art, and his apprentice Sun Liang.

Making Glass Art Known to the World

By Bao Jianyong

He has perfected the art of glass engraving and carving.

When the flywheel turns, he picks up a glass cup with the wheel as the pen, and a piece of glass engraving art can be done in no time. Patterns of flowers, birds, insects and fish are just lifelike,and the inscription fully shows the beauty of Chinese calligraphy.

It is simply a pleasure to watch him perform his glass engraving and carving skills.

Many tourists come here to watch the master’s skills on display. “That was quick!” “Bravo!” Such compliments can be heard almost constantly.

Behind all these lie the unremitting pursuit of glass art and the infinite desire to realize the value of life for Wu Zixiong, a master of Chinese arts and crafts and an inheritor of intangible cultural heritage in Zhejiang province.

Wu has been into the art of glass engraving and carving for more than 60 years. Although he is famous all over the world, he has never changed his true character as a craftsman and always calls himself as such — “an old craftsman”.

On the west side of the People’s Square in Taizhou city, stands a two-story gray building, the Wu Zixiong Glass Art Gallery,which is open to the public free of charge. Whenever there are tourists who come in groups, Wu often acts as a tour guide and starts the grinding wheel to show the charm of the glass art to them.

While visitors are amazed by Wu’s glass artworks, they are more fascinated with his legendary life. From a small beggar to a workshop worker, Wu eventually grew into a world-renowned master of arts and crafts. His glass sculptures are loved by people all over the world and have received more than 30,000 pieces of inscriptions and signatures from foreign friends.

Wu was born in the autumn of 1942, into a rural family in Wuqiao village, Xianju county. In fact, his grandfather was a scholar in the latter years of the Qing dynasty (1616-1911), who had practiced medicine and been a teacher. Wu’s father studied under his grandfather. It was said that on the night Wu was born,his father dreamed of a big black bear running into the house and awoke with a cold sweat. Soon afterwards, his son was born. His father therefore named him Zi Xiong, literally “Son Bear”.

Wu is the sixth child in his family. He has two elder brothers and three elder sisters. At the time of his birth, the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression was in stalemate, and the Wu family was already very poor. The whole family lived in a Buddhist nunnery near the village, and his two elder sisters were given to others as child brides.

In early 1946, Wu’s mother died in poverty and suffering. In 1948, his father started practicing medicine in Haimen (now part of Jiaojiang district, Taizhou city), where he was left to fend for himself with his 10-year-old sister Shaoqiu and 8-year-old brother Hezhong. Half a year later, they were brought to Haimen and reunited with their father.

玻雕作品。A work of glass carving and sculpture.

吴子熊玻雕作品《九七龙庆回归》。Dragons of 97 Celebrating Hong Kong’s Return, a work of glass carving and sculpture by Wu Zixiong.

However, good times did not last, as Wu’s father later died of illness. To survive, Wu’s stepmother had no choice but to remarry. After graduating from primary school, Wu knew that his stepmother lived a hard life as well. Over the years, he sold flatbread and steamed bread, worked as a beggar, and was beaten.Cold and hunger were the norm.

As he grew up, one summer evening, he was walking along the main street in Haimen with nothing to do and feeling restless.Unknowingly, Wu walked to the gate of Haimen Glass Factory,where a middle-aged man wearing shorts was standing in the shade to enjoy the cool.

“Comrade, do you need any apprentices here?” Wu ventured up to ask.

“How old are you, kid?” The man replied in an accent that was not local.

“16.”

“Alright. Please come here tomorrow,” the middle-aged man ruffled Wu’s hair. “We had a vacancy.”

It seemed like the process was so easy.

Thus, Wu’s life trajectory had been inadvertently and forever changed.

He became a worker at the state-owned Haimen Glass Factory. His job was to insert a bamboo rod into the fracture of a variety of glassware still evolving in solution on the hearth and send it to the mouth of an annealing kiln 15 meters away at the fastest speed. Annealing workers holding a long iron fork would take over the ware into the burning annealing kiln.

On average, Wu delivered more than 500 pieces of glassware every day. Within a distance of 15 meters, it was equivalent to a brisk walk of at least 15 kilometers in a high-temperature workshop.

He cherished his job, clocking in early and clocking out late at work, and he worked hard without any complaint. In 1960, Wu was selected by the factory to study for three months at the Lyuda Glass Factory, the biggest in China at the time, together with dozens more from other factories across the country.

In the showroom, vases, flower baskets and overhead lamps of various colors and shapes dazzled. The beautiful goldfish, the peacock and the swimming shrimp were as if they were alive on the crystal jade.

玻雕作品。A work of glass carving and sculpture.

Wu Zixiong was stunned. His peers who came to study with him all wanted to learn the craft. However, the factory guarded its techniques closely, and even taking photos was forbidden. But it was such a rare opportunity for Wu, and he was determined to learn something.

At Wu’s request, he was assigned to visit the engraving and carving workshop. He memorized the exquisite carving skills of the master craftsmen. Every petal, every branch, every connecting pattern, he drew on his palm. When his hand was painted full, he would draw on the cigarette boxes. Back to the dormitory in the evening, Wu would then copy the drawings on the paper.

While the master craftsmen were initially reluctant to teach Wu the craft, he simply worked hard. Every morning, he was the first to the workshop to help them fill the water in the barrel and wipe the machines clean. After work, he helped clean the whole workshop with the on-duty master craftsmen. Learning that the families of three master craftswomen were living a frugal life, he saved his food rations for them.

Eventually, these master craftsmen were moved and taught Wu their unique carving and engraving techniques and skills.During his stay in Lyuda, he also participated in the ceiling lamp carving project of the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.On weekends, he would visit department stores, museums and exhibition halls to look for glass sculptures and engraving patterns,before copying them down. In less than three months, Wu would collect almost 1,000 pieces of designs.

“Glass art is so fascinating that I decided to devote my life to it,” declared Wu.

After his return from the Lyuda Glass Factory, Wu was entrusted with the task of building their own glass sculpture workshop and cultivating more talents. But compared to Lyuda,Haimen’s technologies, mainly relying on sandblasting, were way more backward. The glassware, after sandblasting, could not retain any patterns or designs except for sand marks.

The priority, therefore, was for Wu to manufacture a grinding wheel carving machine. Despite his multiple attempts, they all failed.

He then traveled around and found an old worker named Qiu Zhaofa. Qiu used to work in a glass factory in Shanghai and saw the operation process of Japanese grinding glass technicians.When he returned to Haimen, he bought a pile of discarded small grinding wheels from the factor.

“Can you sell us your grinding wheels?”

“No need to buy, I’d also like to contribute to the development of Haimen Glass Factory.”

Under the guidance of Qiu, a simple grinding wheel carving machine was quickly made. The whole factory was looking forward to the success of the test.

Wu Zixiong was both excited and nervous. He sat down and started the motor, the grinding wheel whirring. He grasped the glass tightly and touched it lightly on the tip of the grinding wheel to create a white arc. Just as he was about to carve a petal, the glass cracked with a snap. He picked up the second glass and there was another crack ... Five times in a row. Five cracks.

The onlooking workers walked away silently one by one,anticipation turning into disappointment. No one is more annoyed than Wu, but no one is more persistent than him.

Undaunted, he went to consult the lathe operator. He was told the speed of the grinding wheels determined their impact and power, which suddenly made him realize the “mistake” he had committed: 1000 revolutions per minute would surely break the glass!

Later, when the speed was adjusted to 400 to 600 revolutions per minute,the first engraved glass product of the factory was soon born. Soon business boomed and the carving machine increased from a single one to 80, even more than Lyuda.

Wu also started to sharpen his skills. He found that those craftsmen at Lyuda were only able to carve but couldn’t draw, and those who could draw didn’t know how to carve. On the contrary,Wu could do both.

Moreover, he integrated the traditional Chinese ink painting art — the lines and compositions of paintings, the strokes of calligraphy and the rhythm of music — into his glass sculptures.

"A flower,a bird,an accidental change,a subtle symbol,all evoke beauty in my heart. I want to carve this beautiful experience into glass works and share it with more people,” Wu said.

In 1978, when the Zhejiang pavilion of the Great Hall of the People was renovated, he was assigned to carve the horseshoe flower patterns on the two glass-engraved wall lamps on the west wing. Later, he wowed his audiences in Beijing, Hong Kong,Shanghai and other places with his exquisite skills.

The name "Wu Zixiong" soon became known internationally.He was invited to Germany, the Netherlands, Britain, Australia,the US,Japan,Singapore,Italy,among other countries.The more he traveled, the more he felt attached to his home country, the more he realized there was still a lack of understanding about China in many parts of the world.

February 6, 1989 was the lunar New Year. Wu was invited to perform at Myer, Australia’s largest chain store, in downtown Brisbane. But when he walked into the luxury mall, he was shocked. In front of him, four bamboo poles supported a thatched hut, with a bamboo ladder, a bonsai and four baskets— a primitive “Chinese household”, quite incongruous with the surroundings.

“It’s not like this in China; I can’t work in a thatched hut,”Wu protested. At his request, the organizer set up another working station and rearranged the site.

Seeing how well-received his performances and his sculptures were in foreign lands, Wu wrote in his diary that “a sense of national pride filled my heart".

Indeed, each piece of glass sculpture has become a bond of friendship between him and thousands of strangers. So far, he has received more than 30,000 inscriptions and signatures from foreign friends, including luminaries and cultural celebrities.

In May 2004, the Wu Zixiong Glass Art Gallery, located on the east side of Taizhou Central Avenue, was completed. A national 3A tourist attraction, the gallery is open to the public free of charge. With the gallery serving as a base spreading spread art and culture in Taizhou, Wu Zixiong’s life has turned a new page.

Just as he showed in the glass sculpture The Power of Lite , life is tenacious.He experienced all kinds of suffering and failure,and in the end these experiences have become the most valuable wealth of his pishing for his continuous efforts towards more successes.

“A horse’s life is a life full of gallops and even its death a horse would maintain a standing position. I want to be like a horse, in this gorgeous world, in this transparent world of glass, constantly tested and always running.”

Because Wu’s Chinese zodiac animal is the horse.

玻雕作品。A work of glass carving and sculpture.