鲍廷博:依运河而居的藏书家

2022-08-26夏春锦陆冬英

文/ 夏春锦 陆冬英

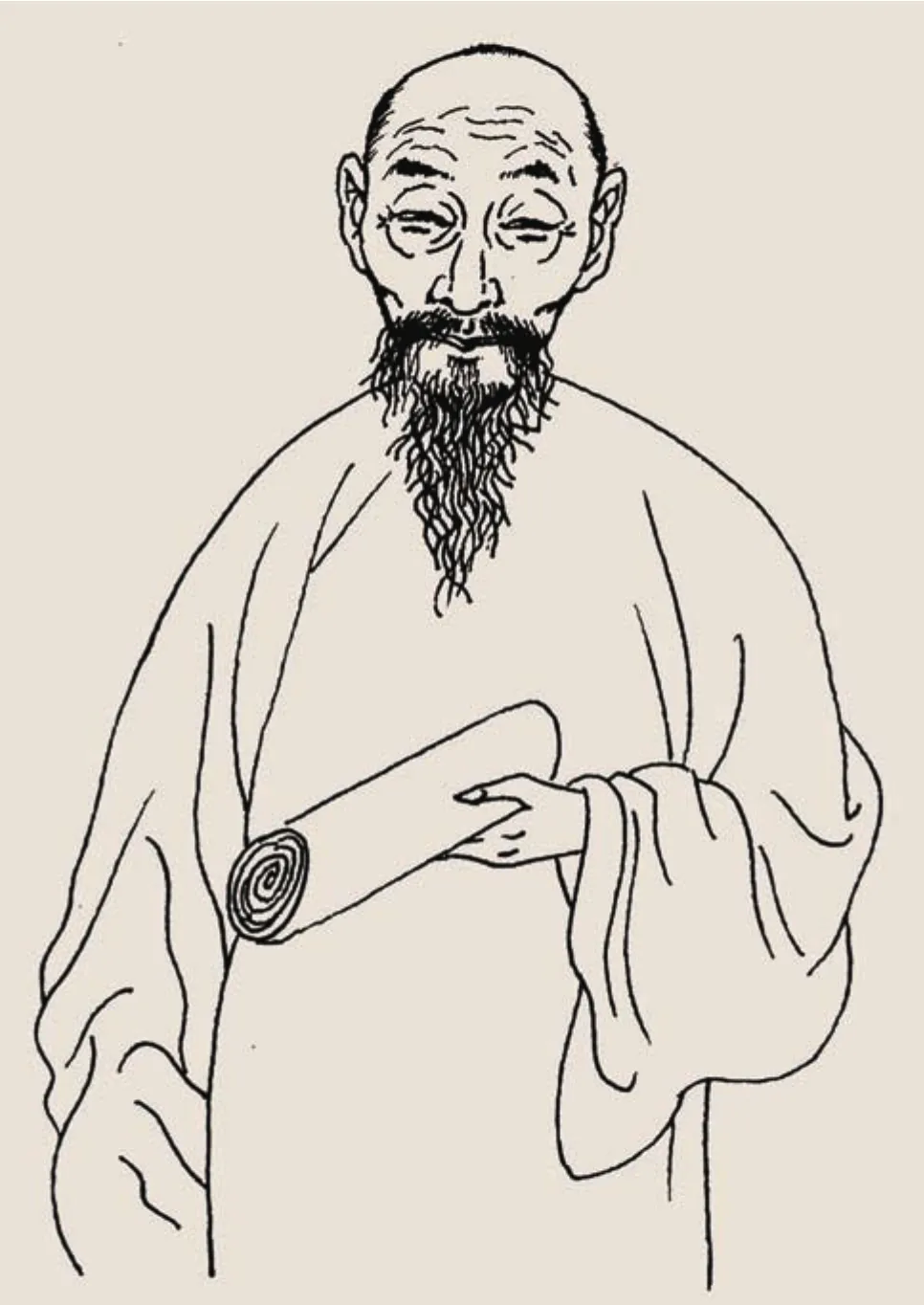

鲍廷博知不足斋。吴蓬/绘Bao Tingbo’s Zhibuzu Zhai (Endless Knowledge Studio). Painted by Wu Peng.

鲍廷博(1728—1814)是清代乾隆、嘉庆年间闻名遐迩的藏书家、刻书家和校勘学家。其祖籍在安徽歙县,自祖父时起寓居杭州,后又移家至桐乡。家有藏书楼名为知不足斋,因清廷修《四库全书》时跻身“天下献书之冠”而受到两代皇帝的礼遇。其精心刊刻的“知不足斋丛书”,亦因校订精审风行海内,成为时人和后世纷纷效仿的典范之作。鲍廷博由此成为中国藏书史上的著名人物,其知不足斋也成为天下读书人为之向往的琅嬛福地。

有研究者著文称,清代百分之八十以上的私家藏书楼都聚集于京杭大运河沿岸,不仅数量丰富,而且所藏之书始终是沿着运河流转。就鲍廷博而言,京杭大运河不仅为他提供了便利的水道交通,更加强了他与各方的联系,他借此得以自由地往来于南北,忙得不亦乐乎。

黄金散尽为藏书

鲍廷博虽出生于徽商之家,但自其祖父鲍贵起就有儒士之风,雅好读书。据记载,鲍氏“先世藏两宋遗集多至三百余家”。这种“贾而好儒”的家风对鲍廷博仁人爱物情怀的养成起到了潜移默化的作用。

鲍廷博一生嗜书如命,不惜重金求购珍本、善本,到了晚年更是因此而倾尽家财,沦落到不得已而鬻书以度残年的境地。鲍廷博生前常用一枚印文为 “黄金散尽为藏书”的藏书印,正是其一生之写照。

早在二十岁之前鲍廷博就已开始大量购书。据乾隆四十一年(1776)朱文藻所作《知不足斋丛书序》云:

盖嗜书累叶如君家者,可谓难矣。三十年来,近自嘉禾、吴兴,远而大江南北,客有异书来售武林者,必先过君之门,或远不可致,则邮书求之……

乾隆四十一年(1776),鲍廷博虚龄四十九岁,往前推三十年,即是二十岁不到的年纪。这一说法与翁广平所说的“二十三岁补歙县庠生,两应省试不售,遂绝意进取,竭力购求典籍”大体吻合。正是有了前期的积累,在其科场失意后才会变本加厉地投入,这份决心和魄力显然是在告知世人,自己将以藏书为毕生志业了。

朱文藻的话揭示了一个重要的史实,即鲍廷博一生的活动范围并不广,除了曾回过徽州,晚年到过北京,其足迹主要还是集中于运河沿线的杭州、嘉兴和苏州等江南地区。这些地方即是鲍廷博开展购书活动的核心区域。

“嘉禾”即嘉兴,“吴兴”即湖州一带,“大江南北”虽是一个比较宽泛的地理概念,但其核心地域则包含了大运河流经的南京、苏州、常州、无锡等地。清代以后,特别是康乾时期,这片地域的工农业生产和商业得到空前发展,文化教育事业也随之迎来了前所未有的繁荣。这其中刻书、藏书等文化活动异常活跃,均达到了封建时代最鼎盛的时期。对于鲍廷博来说,其购书的首选之地就是这一带书贾所开设和经营的书肆、书船,那里品种繁多,选择性大,是其购书的主要来源。

苏州自古繁华,是鲍廷博除了杭州之外去得最多的城市。这源于有清一代,苏州一直是书业最为繁荣的地区之一,有“书肆之盛,比于京师”之誉。乾隆五十四年(1789)十二月二十七日,他就在姑苏城外的紫阳居书肆购得毛氏汲古阁所刻《中吴纪闻》六卷。此书系苏州宋代文人龚明之所著的笔记小说,以记录吴中地区的奇闻轶事和风土民情为主要内容。鲍廷博得书后,将之作为善本进献四库馆,在其身后又被其子鲍士恭刻入“知不足斋丛书”第三十集,得以流布士林。

湖州作为著名的藏书和刻书之乡,也是鲍廷博时常到访的地方。乾隆三十六年(1771),他受挚友吴骞之托,多年寻觅《千顷堂书目》而不得,后“始从苕估购得”一套旧抄本,才完成了朋友的夙愿。

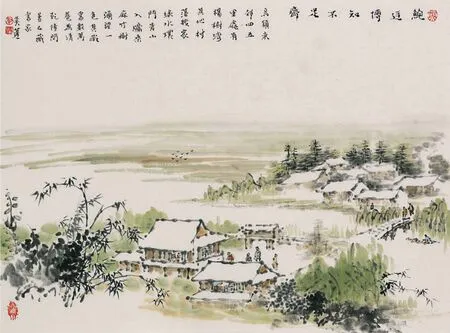

鲍廷博旧藏宋淳熙刻本《金石录》十卷。上海图书馆藏。The Song edition of Record of Bronze and Stone Inscriptions in 10 volumes, which were acquired by Bao Tingbo. They are now collected by the Shanghai Library.

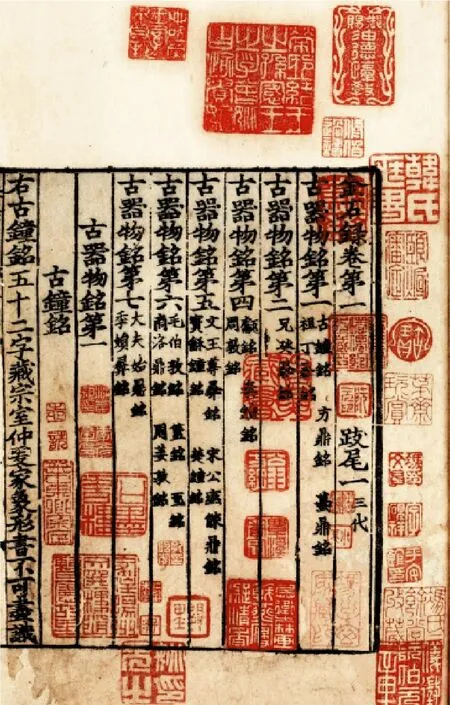

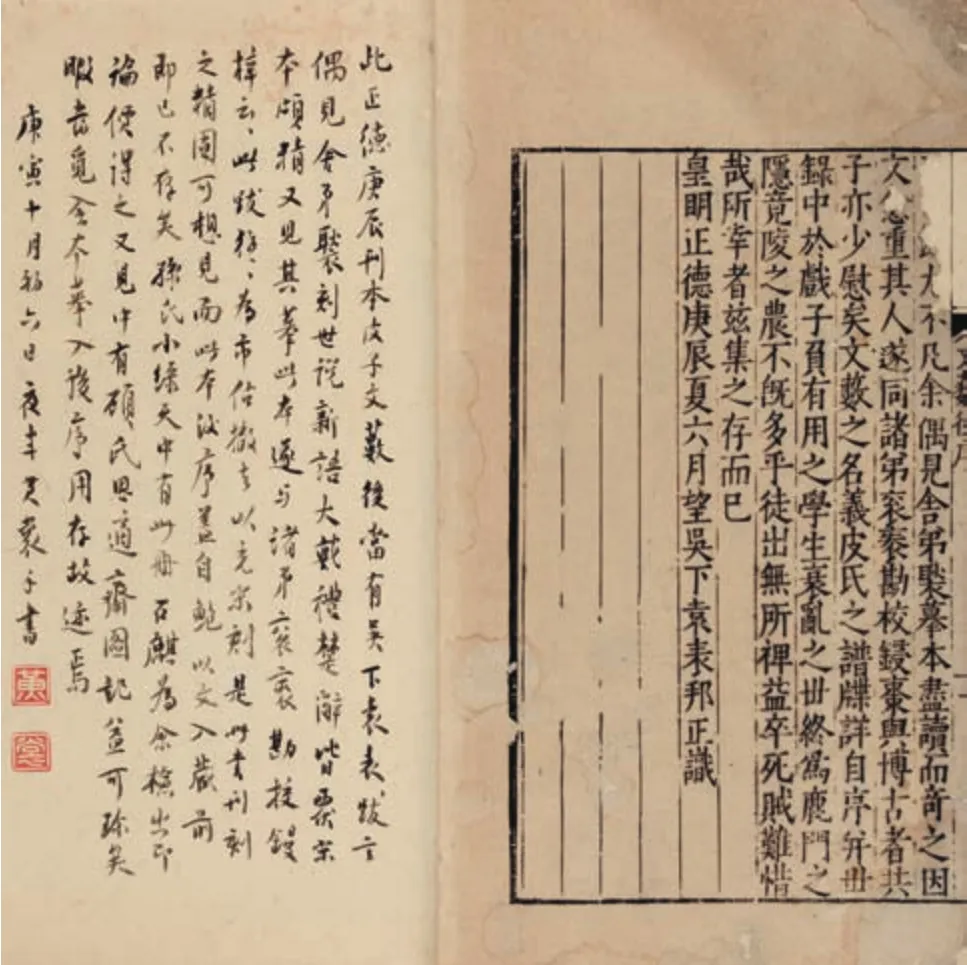

鲍廷博旧藏明正德刻本《皮子文薮》,黄裳与其夫人曾六次题跋。A Mélange of Essays by Pi Rixiu, a Ming dynasty edition acquired by Bao Tingbo.

鲍廷博的藏书印。Bao Tingbo’s ex libris seals.

吴骞所说的“苕估”又称“苕贾”“苕上书估”,是对当时十分活跃又独具特色的湖州书贾的泛称。湖州书贾最大的特点是常以船贩书,世称“湖州书船”,他们借助四通八达的水网河道,特别是便利的运河水道,浮家泛宅,往来于江浙之间,所到之处,常常受到士大夫的礼遇。

鲍廷博还从湖州书贾手上购得极为珍贵的宋版《金石录》三十卷。此书是宋代赵明诚、李清照夫妇的心血之作,而宋版《金石录》更是稀世珍品。这一部仅为十卷,系北宋淳熙刻本,原为嘉兴冯文昌所藏。书后来流落江湖,辗转于阮元、潘祖荫等众多藏书家之手。今藏于上海图书馆。

藏家之间互通有无

在鲍廷博的青年时代,借抄是仅次于购买的最主要的聚书方式。其老友朱文藻曾记录下一份与其互为借录的藏书家名单,总共九家,位于杭州的有六家,分别为郁氏东啸轩、汪氏振绮堂、吴氏瓶花斋、赵氏小山堂、卢氏抱经堂、孙氏寿松堂;位于嘉兴的有两家,海宁的吴氏拜经楼和桐乡的金氏桐华馆;位于宁波的仅一家,即慈溪的郑氏二老阁。从地域分布来看,这些藏书家主要集中于浙江省内,且都是江南运河和浙东运河流经的城市。但朱文藻罗列的并非全部,像杭州城内厉鹗的樊榭山房、汪启淑的飞鸿堂,桐乡金氏的文瑞楼,还有位于苏州的不少藏书家都没有被提及,加上这些才共同组成了鲍廷博借阅传抄的超强阵容。

目前可知,鲍廷博最早抄书的时间不晚于乾隆二十年(1755),时年二十八岁。在这一年当中,他先后抄录过四部书,其中孙承泽的《庚子销夏记》八卷明确交代是“偶于吴下抄得之”,因此书内容精审,得之不易,“窃有贫儿暴富之喜”。

在鲍廷博所抄录的书籍中,质量最高、品种最理想的部分主要就来自他的这个运河边上的朋友圈。与此同时,那些生活在运河沿岸的好友如海宁吴骞、仁和朱文藻、嘉兴戴光曾等也从知不足斋借抄和受赠了不少好书。

运河边上的藏书家之间除了彼此借抄,还可以通过相互转让,以购买的方式从其他藏书楼获得心仪之书。这类书往往最对藏书家的胃口,有些甚至是自己朝思暮想而不可得者。早年,鲍廷博就从钱塘藏书家吴允嘉(1657—?)营构的四古堂购得五代时期和凝、和㠓父子合著的《疑狱集》三卷。

在定居桐乡之前,鲍廷博已与桐乡本地的藏书家多有来往。最早的一次是乾隆二十七年(1762)冬,偕吴长元专程拜访世居运河边上的甑山钱氏,向其借书。而与鲍廷博有私交的则是已经迁居苏州桃花坞的金氏文瑞楼,鲍廷博曾从该楼购得宋朱翌所著《猗觉寮杂记》抄本。仍留在桐乡的金德舆和金锡鬯叔侄,也都热衷于收藏,两人都成为鲍廷博的莫逆之交。

此外,鲍廷博还有过多次向其他苏州藏书家购书的经历。如乾隆三十年(1765)八月二日,从木渎璜川书屋购得元代郑元祐所著《侨吴集》明弘治刻本。他还曾以高价向吴江沈氏购得宋代钱文子著《补汉兵志》抄本一卷。

寓居桐乡

鲍廷博与运河更亲密的接触是在定居桐乡之后。他依托京杭大运河,时常往返于以桐乡为中心点的苏杭间。当时他走得最多的是京杭大运河的南段,即江南运河。该线自镇江的谏壁口,经常州、无锡、苏州、嘉兴至杭州,最终汇入钱塘江。

如乾隆五十二年(1787)春,鲍廷博偕吴骞、吴翌凤泛舟吴江,拜访好友杨复吉,在杨府巧遇同时到访的王鸣盛,彼此得以诗酒为乐。吴骞有诗纪事,云:

其一

蹑屐下姑苏,扬帆径石湖。为怜扬子宅,可钓季鹰鲈。

屏拓峰千叠,楼高酒百壶。此中容啸傲,身世一菰芦。

其二

远塔垂虹外,孤城钓雪边。碧萝三径雨,芳树五湖烟。

客至巾初垫,春移景未迁。三高祠下水,相与定忘年。

在交通不便的古代,身居异地的朋友们见面的机会并不多,但有限的次数反而使得彼此的友谊更加牢固。

因为船行较慢,鲍廷博经常携带书籍出行,于舟中校书成为他的一个习惯。据书上的一些题跋显示,他曾于乾隆五十三年(1788)十二月二十七日“舣舟吴江”,同日又校宋刻本《云庄四六余话》“于平望舟次”。嘉庆九年(1804)岁末,鲍廷博有过一次苏州之行,于舟中校阅明末汲古阁刻本《剑南诗稿》,有题识写道:

甲子十一月十一日,次万年桥阅。薄暮过五龙桥,乘月渡太湖,水天一色,风平无波,天下绝景也,惜无放翁妙笔作一诗咏之。是日得吴枚庵兄手抄《游志续编》,又得《马石田集》四册,快正。泊吴江南门外,读《游志》,烛尽始睡去。

万年桥坐落于苏州胥门外的护城河之上。五龙桥则是苏州城南太湖水的进入口,其南面即是京杭大运河。题识中留下的这些地名和桥名,记录着鲍廷博的运河行程,成为研究藏书家与运河关系的第一手史料。

移居桐乡后,鲍廷博仍不顾年老体衰,时常光顾杭州的书肆,泛舟沿运河出行,一个来回往往要花费数天时间。八十四岁那年(1811)的八月九日,他从桐乡赶到杭州城内的积书堂,购得宋宗室赵与容所著《辛巳泣蕲录》手抄本一卷。回家后于题识中记道:

月十二日阅于菜市桥舟次。十四日舟过谢村,校雠粗毕,与二孙正字舟中看月,至新墅始就睡。十五日午刻抵家记。(陆心源《皕宋楼藏书志》卷二十四)

跋文中写到的新墅即德清新市,他们乘船从杭州拱宸桥附近的北关出发,走谢村、十二里漾、塘栖、新市、含山、练市,再到乌镇。其中杭州北关到塘栖这一段,就是明清的漕运河。到塘栖后,之所以不走崇德县方向,是因为沿新市方向从烂溪回乌镇,路程相对更近。这条水路在鲍廷博的题跋中多有记载,可见是其往返于杭州和桐乡之间的首选路线。

从塘栖经大麻、崇德到桐乡的是下塘河,虽然路程相对较远,但鲍廷博并非从来不走,毕竟经过清初的疏浚,这条水道更加宽阔和安全。如嘉庆四年(1799)十一月二十九日,他于行舟中校毕旧抄本《艮斋诗集》,题识中明确记载是在“舟次大麻”时完成的,显然走的就是这段运河水路。

某种意义上,鲍廷博最终选择桐乡作为其家族的定居之地,运河应该是一个重要的因素。这对于他的藏书刻书事业、文化视野和人生格局,都发挥了积极的意义。

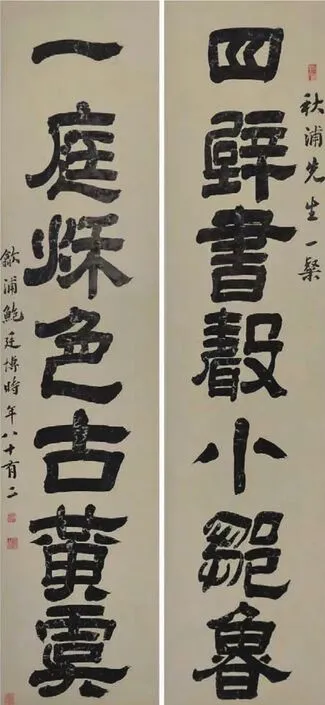

鲍廷博七言联。南京博物院藏。One couplet written by Bao Tingbo, collected at the Nanjing Museum.

A Bibliophile Living along the Grand Canal

By Xia Chunjin Lu Dongying

Bao Tingbo (1728-1814) was a renowned bibliophile with a good reputation as block printer and textual critic in the Qing dynasty (1616-1911). While his ancestral hometown was Shexian, Anhui, he lived in Hangzhou with his grandfather and later moved to Tongxiang. In 1772, Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) ordered the compilation of() and the Bao family presented the largest number of rare books from their private library named Zhibuzu Zhai (or the Endless Knowledge Studio),for which they were awarded by both Emperor Qianlong and his successor, Emperor Jiaqing (1760-1820). Bao’s meticulously collated() was popular in China, setting an example for his contemporaries and future generations. His great contribution made him a noted figure in China’s history of book collecting and his family library, a paradise for book lovers. Research has found that over 80 percent of private libraries in the Qing dynasty were located along the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal. They featured massive collections of books circulating among the bibliophiles. The convenient canal transport enabled Bao to travel freely between the southern and the northern parts of China and to build strong connections with his friends and business partners.

A merchant as he was, Bao Gui, grandfather of Bao Tingbo,loved reading and made it a family tradition. Records show that the merchant family amassed an impressive book collection of over three hundred Song dynasty (960-1279) writers, an important family legacy that exerted an invisible yet formative influence on Bao Tingbo’s love for books. An avid book collector, Bao poured all his money into book collecting. In his later years, he was reduced to selling books for a living after he spent his last penny on books. The life of the bibliophile was a true reflection of his ex libris seal inscription: “No expense is spared in book collecting.”

知不足斋主人渌饮先生遗像(杨澥原绘,华克齐临摹,选自《鲍廷博年谱长编》)。Portrait of the master of Zhibuzu Zhai (Endless Knowledge Studio).

It is documented that Bao started to buy large quantities of books before he was 20. He tremendously increased his investment after his failures in the imperial civil service examination, as a testament to his steely determination to be a lifelong bibliophile.According towritten by Bao’s friend Zhu Wenzao in 1776, apart from occasional return to his ancestral hometown and a brief stay in Beijing in his old age, Bao stayed mainly in the cities along the Grand Canal such as Hangzhou, Jiaxing and Suzhou, which constituted the main areas of his collecting activities.

In the early Qing dynasty, these regions saw unprecedented growth in industry, agriculture and commerce and such developments were accompanied by an exceptional rise of literary pursuits, particularly book engraving and book collecting, both of which reached their heyday in the feudal age. That explains why Bao was a frequent visitor to the book shops and book boats in the above-mentioned canal areas whose great varieties spoiled him for choice.

Suzhou, a prosperous city since ancient China, was Bao’s second most visited destination after Hangzhou. In the Qing dynasty, it was hailed as one of the largest centers for book trade,boasting as many bookstores as those in Beijing. On February 10,1790, Bao bought the six-volumeby Gong Mingzhi (1090-1182?) who recorded the customs of Suzhou. The woodblock print Bao obtained from a bookstore outside Suzhou was produced by the private library cum publishing house set up by Mao Jin (1599-1659). Later, Bao presented the highly prized book to the editorial board of. After he passed away, his son Bao Shigong produced a block print of the book and made it the 30th volume of Endless, facilitating its wide circulation among the literati.

Huzhou, a center for book collecting and book engraving,was also where Bao frequented. In 1771, after many years of fruitless attempts to find, he finally managed to get a collection of old manual copies from a book trader in Huzhou, fulfilling a long-cherished wish of his bosom friend Wu Qian. Another book Bao acquired from a book dealer there was the extremely rare Song edition of the 30-volume, the lifelong undertaking of the epigrapher Zhao Mingcheng (1081-1129)and his intellectual wife, Li Qingzhao (1084-1155). The woodcut print Bao obtained consisted of 10 volumes only. Originally a collection of Feng Wenchang, a bibliophile in Jiaxing, it later became the possession of different private book collectors like Ruan Yuan and Pan Zumeng. Presently, the books are kept in the Shanghai Library. The active book merchants of Huzhou were particularly notable for their book boats. They lived and traveled in their mobile bookstores that frequented the areas between the Yangtze River and the Qiantang River through the convenient waterway network, especially the Grand Canal. Wherever they were, they were treated with courtesy by local officials and literati.

In his youth, Bao borrowed books from collectors and copied them by hand, the second commonly used method to collect books. Zhu Wenzao made a list of nine bibliophiles with whom Bao exchanged books for copying. Of them, six were in Hangzhou,two in Jiaxing, and one in Ningbo, mostly located in the cities along theCanal (the section of the Grand Canal south of the Yangtze River) and the Eastern Zhejiang Canal. Nevertheless,the list would have been a comprehensive manifestation of Bao’s transcribing efforts, had Zhu included in it other prominent bibliophiles in Hangzhou, Tongxiang and Suzhou who exchanged books with Bao, too.

Records show that Bao started to copy books as early as in 1755 when he was 28. One of the four books he copied in that year was eight volumes of1660, a collection of paintings, rubbings and calligraphic works compiled by Sun Chengze. It was specifically documented that Bao chanced upon the treasured edition in Suzhou and made a written copy of it,describing his surprise and joy at obtaining it as “that of a beggar becoming rich overnight”. Of all the books Bao copied, the best came from his friends residing near the Grand Canal who borrowed, copied and received quite a few valuable books as gifts from Bao as well.

Apart from exchanging books for copying, the bibliophiles living near the Grand Canal traded books in their collections with each other to get their long-wished-for books. For example, Bao purchased from Wu Yunjia (1657-?) in Hangzhou three volumes ofco-written by He Ning and his son He Meng in the Later Jin dynasty (936-947).

Long before Bao moved to Tongxiang, he had had many contacts with local book collectors. As early as in the winter of 1762, together with his friend Wu Changyuan, he traveled long distances to visit the Qian family for borrowing books. The Qians had been living in northern Tongxiang for generations.Additionally, he made good friends with another two local bibliophiles Jin Deyu and his nephew Jin Xichang, who chose to stay in Tongxiang despite their family’s relocation to Suzhou. Bao purchased from the Jin family’s private library a handwritten copy of, an anthology of essays on poems penned by the Song dynasty scholar Zhu Yi (1097-1167)during his stay at a monastic residence.

Bao bought books from bibliophiles in Suzhou as well. For instance, he acquired from the private library of the Wu family a Ming dynasty (1368-1644) woodblock print of, an anthology of poetry and essays authored by Zheng Yuanyou (1292-1364) while in Suzhou. Further, Bao purchased from the Shen family at enormous personal expense a manuscript ofwritten by the Song dynasty scholar Qian Wenzi.

After he moved to Tongxiang which was located between Suzhou and Hangzhou, where Bao traveled oftentimes via the Grand Canal, particularly the Jiangnan Canal, a route which started from Zhenjiang and passed through Changzhou, Wuxi,Suzhou and Jiaxing to Hangzhou before it finally merged into the Qiantang River.

In the spring of 1787, Bao took a boat trip on the Wujiang River with his two friends to visit Yang Fuji in Suzhou where the three of them bumped into Wang Mingsheng, an outstanding historian, who was also paying Yang a visit. The pleasant encounter allowed them to enjoy poetry composition over cups of wine. In ancient times when transportation was not so convenient, distant friends did not have many opportunities to meet face-to-face,which strengthened their friendships rather than the other way around.

As boat trips took more time, Bao, who always had books with him wherever he went, made a habit of collating books on his journeys. According to his prefaces and postscripts, his boat was anchored in the Wujiang River near Suzhou on January 22, 1789,and on the same day, while the boat was in dock at Pingwang,Suzhou, he collated the Song woodblock edition of. At the end of 1804, he took another boat trip to Suzhou during which he collated the late Ming dynasty woodcut edition ofHis postscript that showed his Canal boating route became a primary source for research on the relationships between the bibliophile and the Grand Canal.

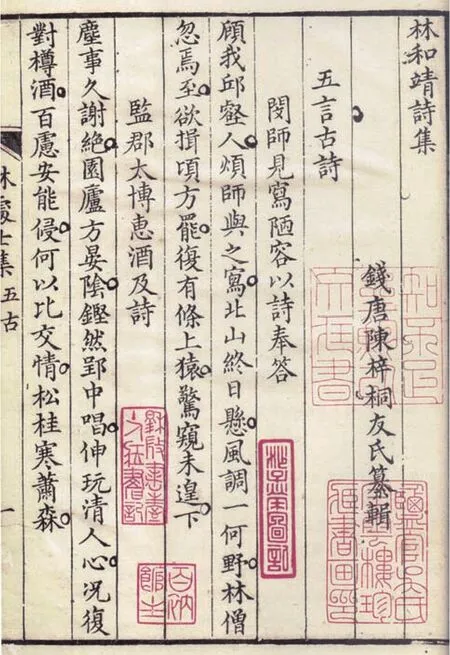

鲍廷博批校过的清乾隆十年深柳读书堂刻本《宋林和靖先生诗集》卷首。(现藏于芷兰斋)The front page of An Anthology of Li Hejing’s Poetry, which had been annotated by Bao Tingbo.

After moving to Tongxiang, Bao, regardless of the agingassociated physical decline, patronized bookstores in Hangzhou through multi-day boat trips. On September 26, 1811, when he was 84, he obtained a handwritten copy of:by Zhao Yurong, a member of the Song imperial clan. Back home, Bao wrote in his postscript:

The above-mentioned Xinshu was actually Xinshi, a small town in Deqing. The postscript indicated that they set off from Beiguan near the Gongchen Bridge in Hangzhou and traveled through Xiecun, Shi’erliyang, Tangxi, Xinshi, Hanshan, Lianshi before they reached Wuzhen in Tongxiang. The first half of the route, namely, the section from Beiguan to Tangxi was part of the Grand Canal. For the second half, they opted for Xinshi instead of Chongde county because the former was closer to the destination. The whole route appeared in many of Bao’s prefaces and postscripts, which suggests it was his choice when traveling between Hangzhou and Tongxiang.

An alternative route to Tongxiang went through Tangxi,Dama and Chongde, along a branch of the Grand Canal called the Xiatang River. It remained one of Bao’s options because the dredging project in the early Qing dynasty had made the waterway wider and safer, though it entailed longer travel time. The boat trip in 1799 was a case in point. On December 25, he completed collating an old copy of(Genzhai was a Vietnamese poet) on the journey and the final work, according to his postscript, was done while the boat lay “at anchor at Dama”, which demonstrated that the alternative route was in use.

In a sense, Bao Tingbo’s decision to relocate his family to Tongxiang had a lot to do with the Grand Canal, a move which contributed to his career as a bibliophile, expanded his horizons as a scholar, and broadened his perspective on life.