Successful withdrawal of antiviral treatment in two HBV-related liver transplant recipients after hepatitis B vaccination with long-term follow-up

2022-01-07MnXieYunJinZngBeiZhngWeiRo

Mn Xie , Yun-Jin Zng , c , Bei Zhng , Wei Ro , c,*

a Department of Gastroenterology, the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao 266600, China

b Division of Hepatology, Liver Disease Center, the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao 266600, China

c Department of Organ Transplantation, the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao 266600, China

d Department of Immunology, Medical College of Qingdao University, Qingdao 266071, China

TotheEditor:

Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) combined with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) has become the standard regimen for preventing recurrence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in HBV-related liver transplant (LT) recipients. HBsAg seropositivity was detected in only 7.2%-8.6% of LT recipients who received monotherapy with high-genetic-barrier NAs after a short period of combined therapy [ 1 , 2 ]. Despite progress in the application of newer NAs in HBV-related LT recipients, complete withdrawal of HBV prophylaxis after LT was controversial and considered risky by some centers [3] . We here present two cases of complete and sustained HBV cccDNA-negative status after withdrawal of prophylaxis when intrahepatic and active immune response was achieved with hepatitis B vaccination. Our experience provides a strategy for reliable and safe withdrawal of anti-HBV prophylaxis in HBV-related LT recipients.

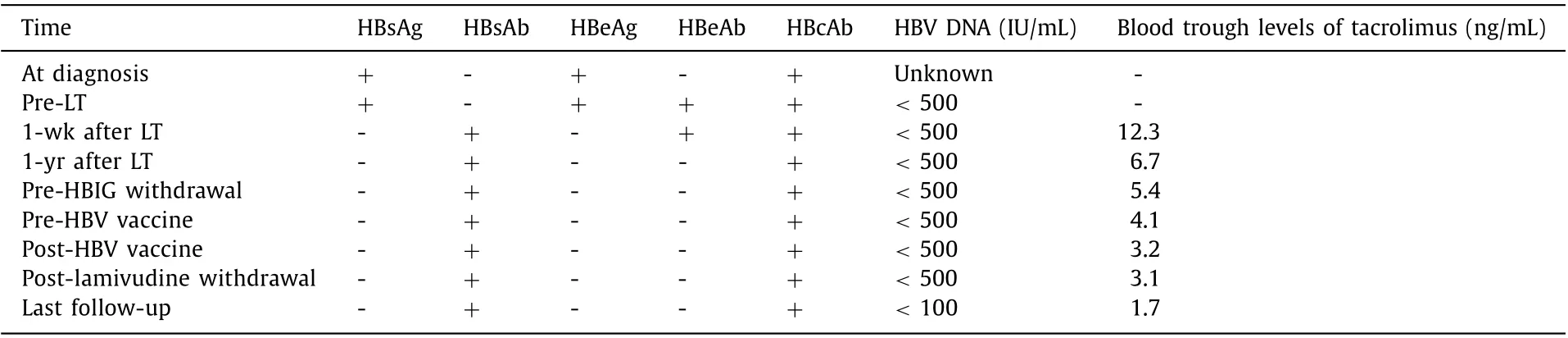

Patient A: A 33-year-old male had HBV infection diagnosed in childhood but received no antiviral therapy before LT, which was performed for acute-on-chronic liver failure on August 2005 when he was 18. The model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) score before LT was 32. After LT, a tacrolimus-based immunosuppressive regimen was administered which included corticosteroids for 6 months. The serologic and virologic status of HBV and the trough levels of tacrolimus after LT were shown in Table 1 . Anti-HBV prophylaxis regimen including HBIG combined with lamivudine was prescribed after LT. 40 0 0 IU HBIG was given intravenously during the anhepatic phase, and 20 0 0 IU HBIG was given daily for the first 7 days. Thereafter, HBIG was given on-demand at a dose of 400 IU intramuscularly to keep the serum anti-HBs titer above 200 IU/L until 6 months after LT and to keep it above 100 IU/mL after that. Three years after LT, HBV DNA and HBV cccDNA in liver biopsy were negative, as assessed using previously reported techniques [4] . After that, HBIG was discontinued and HBV vaccine (EngerixB, GSK, Brentford, Middlesex, UK) 40 IU was injected monthly until the anti-HBs titer>100 IU/mL which was continued on-demand to maintain a stable titer. Forty-six months after LT,lamivudine was discontinued. A second liver biopsy was performed 12 months after the patient had been weaned off antiviral therapy,and intrahepatic HBV DNA and HBV cccDNA were still negative. After 128 months of complete withdrawal of antiviral treatment (174 months after LT), HBV had not recurred. Liver function tests were stable throughout the follow-up period.

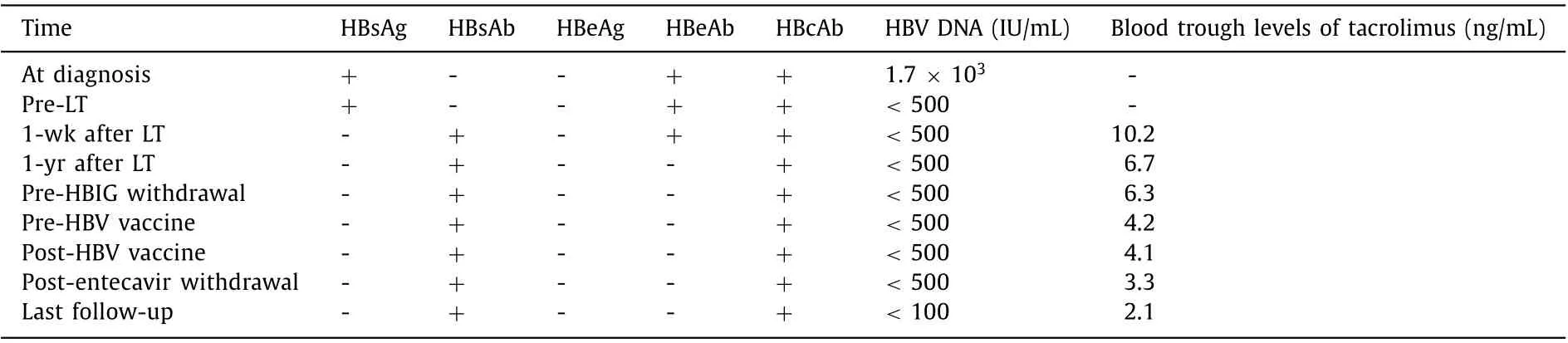

Patient B: A 42-year-old male who had been diagnosed with HBV infection at age 18 had decompensated liver cirrhosis at age 27. Then he was treated with entecavir and experienced a complete virologic response 3 months later. However, the patient still received LT for repeated gastrointestinal bleeding during April 2008 at age 30. The MELD score before LT was 28. After LT, he received a tacrolimus-based immunosuppressive regimen. The serologic and virologic status of HBV and the trough levels of tacrolimus were listed in Table 2 . After LT, the patient received anti-HBV prophylaxis including entecavir combined with HBIG by a protocol like that of patient A. Intrahepatic HBV DNA and HBV cccDNA in a liver biopsy performed 47 months after LT were negative. After that,HBIG was discontinued and HBV vaccine (EngerixB, GSK) 40 IU was injected monthly. After anti-HBs titer exceeded 100 IU/mL for one more year, entecavir was discontinued (60 months after LT). In another two liver biopsies performed 67 months and 88 months after LT, intrahepatic HBV DNA and HBV cccDNA remained negative. No recurrence of HBV was observed 82 months after complete withdrawal of antiviral treatment (142 months after LT). Graft function was stable during the follow-up period.

In these two HBV-related LT recipients, firstly, active immune response was maintained with HBV vaccination and tests came back negative for intrahepatic HBV DNA and HBV cccDNA in liver biopsy tissues. Secondly, NA and HBIG treatment were discontinued and the patients did not use any treatment for a long time. No HBV recurrence was observed. Although we cannot make any recommendations based on this limited experience, the results suggest criteria for safe withdrawal of anti-HBV prophylaxis in HBVrelated LT recipients. This information is especially useful becauseliterature reports on this subject are sparse and inconclusive, and consensus guidelines have not been established.

Table 1 Serologic and virologic status of HBV and trough levels of tacrolimus of patient A.

Table 2 Serologic and virologic status of HBV and trough levels of tacrolimus of patient B.

Attempts have been made to discontinue antiviral therapy completely after a period of combined prophylaxis therapy in LT recipients, and the HBV recurrence rate has been reported to be 5.6% to 20% [ 3 , 5-7 ]. In studies by Lenci et al. [ 3 , 5 ], antiviral therapy was discontinued completely without HBV vaccination. In a study by Duan et al. [6] , HBIG and NA were withdrawn in a stepwise fashion after active response of HBV vaccine was observed. Intrahepatic HBV cccDNA was not measured in any of these studies mentioned above.

With antiviral prophylaxis therapy, some LT recipients were HBsAg negative, but the intrahepatic HBV DNA and/or HBV cccDNA were positive, which indicated occult HBV infection. Although antiviral treatment has not been recommended generally for treatment of occult HBV infection, patients’ immunocompromised state or defective HBV immunity has prompted clinicians to prescribe antiviral therapy to prevent HBV recurrence [4] . However, it has been unclear whether this prophylaxis need to be lifelong, especially when the blood concentration of immunosuppressant is decreased. Intrahepatic total HBV DNA has been detected in more than 80% of recipients and cccDNA in 28%-51.6% of recipients with HBIG or NAs monotherapy. However, a recent study showed that the incidence of occult HBV infection may be significantly lower among the recipients with combined prophylaxis therapy [4] . Of note, the detection rate of occult HBV infection in LT recipients could become higher with improved technology, such as droplet digital PCR. It seemed reasonable that LT recipients with low viral load had a lower risk of HBV recurrence after withdrawal of prophylaxis therapy. Therefore, we strongly recommended that the intrahepatic HBV DNA and HBV cccDNA test be performed before withdrawal of antiviral therapy.

HBV vaccination has not become standard therapy for prevention of HBV recurrence after LT because of the uncertain response(24.6%-51.8%) [6-9] , which was significantly lower than that in the general population. It remains unclear whether the active immune response to the vaccine could be maintained for a long-term.In these two cases, the serum anti-HBs titer was remained over 100 IU/mL for more than one year with repeated vaccination, and the titer decreased more slowly than expected after active immunity was maintained.

Although some uncertainty remains, it seems reasonable that in HBV-related LT recipients, when intrahepatic HBV cccDNA was negative and active response to vaccine appeared, complete withdrawal of long-term antiviral treatment could be feasible. In the future, prophylaxis protocols for HBV after LT might be further refined to reduce unnecessary treatment and expense in the application of this strategy.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Man Xie: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Yun-Jin Zang: Project administration, Writing - review &editing. Bei Zhang: Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review& editing. Wei Rao: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the “Clinical medicine + X” Foundation of Medical College of Qingdao University (2017223).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma with sarcomatous change:Clinicopathological features and outcomes

- Successful treatment of complete traumatic transection of the suprahepatic inferior vena cava with veno-venous and cardiopulmonary bypass with hypothermic circulatory arrest ✩

- High perioperative lactate levels and decreased lactate clearance are associated with increased incidence of posthepatectomy liver failure

- An NSQIP survey of outcomes after resection of choledochal cysts in adults

- Glucagonoma syndrome with necrolytic migratory erythema as initial manifestation

- A rare type of choledochal cysts of Todani type IV-B with typical pancreaticobiliary maljunction