Engaging in scientif ic peer review: tips for young reviewers

2021-12-24EvgeniosAgathokleous

Evgenios Agathokleous 1

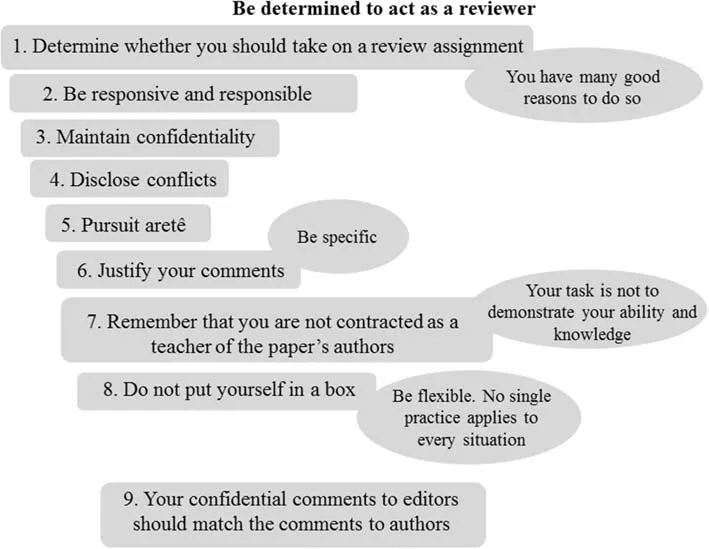

Abstract Are you a student at a higher institution or a graduate who has published his/her f irst paper in the Journal of Forestry Research or another legitimate scientif ic journal? If yes, this paper is written specif ically for you since you may soon start receiving invitations to act as a referee.If you are an early career reviewer, you may still f ind this paper enlightening. Based on his experience, a senior editor summarizes some critical information that, in his view, you may need to know. He provides nine main suggestions to have on your radar, and discusses what you should do or not do as a peer reviewer.

Keywords Academic editor · Peer review · Referees ·Reviewer role · Scientif ic publishing

Why should you agree to review a paper?

In a previous paper, I have analyzed the peer-review process for beginner authors (Agathokleous 2022). If you have published your f irst article in the Journal of Forestry Research or another legitimate scientif ic journal, be prepared to serve as a reviewer too (Fig. 1), especially if you are the designated corresponding author of your published paper.

Avoidance of stimuli or situations that are perceived threatening is a characteristic of adaptive fear (Krypotos et al. 2015). If you have never reviewed before, do not worry about your ability and performance. The editor probably knows that the chances you have reviewed before are extremely low. I bet he/she does not depend solely on your review report, but in any case you can always clarify to the editor that this is your f irst experience. Yes, you can input conf idential comments that only editors will see. Bear in mind that an editor may also want to train you. Prof icient and highly proactive editors often invest time to expanding their reviewer pool, thus an editor may want to give you a chance to experience reviewing; you may be invited in addition to an existing minimum number of experienced reviewers. Hence,do not fear to accept an invitation to review.

Reviewers are sentinels of science (Fig. 2), and the success and progress of science depends on the reviewers’ diligent work. Editors’ decisions largely depend upon reviewers’recommendations, and can f inally impact the directions in specif ic research areas, and, thus, the progress of scientif ic advance, accumulation of scientif ic knowledge, and societal development. Hence, peer review, including reviewer’s roles and responsibilities, is a widely discussed subject in the published literature (suggestions for further reading:Bloom 1999 ; Brazeau et al. 2008 ; Kotsis and Chung 2014;Rodríguez-Bravo et al. 2017; Chung 2019; Glonti et al.2019; Dhillon 2021). Because reviewing is tightly linked with authoring, and given the importance of peer review,you should actively contribute to peer review. Since you published and others were committed to review your paper,you should also review others’ papers. Even if you do not know it, you may often review a paper authored by reviewers of a paper you published and vice versa. Another important reason why you should agree reviewing a paper is that documented peer review record can help your career’s development.For example, a major determinant of academic evaluations for the promotion of faculty members is international recognition, and this includes peer review record, which relates to reputation and international visibility and recognition as an expert in your research areas. Many universities around the world mandate the proof of peer reviewer record.Some funders also ask to list experience as peer reviewer.Finally, scientists often assume editorial roles based on their diligent work as reviewers. Hence, by being a diligent,responsive, and responsible reviewer, you may fi nd yourself on editorial boards of journals. There are many ways that someone can get credit for their work as reviewers, including well-known platforms such as Publons ( https:// publons. com/ ) and Reviewer Credits ( https:// www. revie wercr edits. com/ ), of which some off er even awards to excellent reviewers. Many journals also publish acknowledgements to reviewers, including their names (not associated with specifi c manuscript without your permission), which may be seen as an additional recognition. By contributing as a reviewer, you can build a better relationship with a journal, and this is a positive outcome. But beyond these, reviewing papers keeps you informed on the most recent developmentsin your fi eld and transforms you into a better author. Writing papers is an acquired skill that can be developed through reading and reviewing.

Fig. 1 Tips to consider regarding your peer reviewer role

Fig. 2 Research scientists are “condemned” to hold up the weight of humanity and Earth. In Greek mythology, titanomachy (Titan battle)were battles that took place in Thessaly over a period of ten years. In these battles Titans, an older generation of Greek gods of Mount Othrys led by Atlas, fought against Olympians, the younger generations of Greek gods led by Zeus that would come to sovereignize Mount Olympus. The two parties fought over which generation would dominate the universe, and the battles ended with the victory of the Olympians. This resulted in the Olympians taking over the universe and Atlas being condemned to hold up the celestial sphere (heavens or sky) for eternity. This is only a metaphor inspired by Greek mythology to emphasize the weight of responsibility of scientists toward the world while making the paper more entertaining, and should not be translated literally. The f igure was created based on a plant that reminded Atlas to the author of this paper

Be responsive and responsible

When you receive an invitation to review a paper, judge whether you are willing to accept it or not as soon as possible. If you know immediately that you are not going to accept it, let the editor know by turning down the invitation.Do not wait some days to do so because this may cause unnecessary delays to the peer review of the specif ic paper(Dhillon 2021). As you do not want your own paper to have a slow and overly delayed peer review, respect other authors by not causing to them what you do not want for yourself. There is a due date somewhere written in the review invitation you have received. Do your best to accept the invitation (if you will do) by the due date. When you consider accepting reviewing a paper, it is important that you read the journal’s peer review policies. In particular, be informed whether the journal mandates the public display of the reviewers’ identity on the papers and/or the publication (commonly online only) of review reports following acceptance and upon publication of the reviewed paper.This may be especially important for those who are at the beginning or early stages of their career. Studies suggest that early-career researchers like blind double-peer review,where both authors’ and reviewers’ names are blinded, and most of them f ind the open peer review uncomfortable (Rodríguez-Bravo et al. 2017). Therefore, consider these aspects prior to accepting or declining an invitation to review; for further information regarding dif ferent peer-review models see Dhillon ( 2021). If you accept an invitation to review a paper, do your best to be responsible and submit your review report by the deadline indicated in the email thanking you for agreeing to review. Things change, and editors understand that circumstances might induce your need for more time. If this is the case, contact the journal’s of fice as soon as you know it and request an extension of the deadline—specify how much more time you expect to need. Failure to submit your review report in due time without any notif ication can lead to editors creating a bad image for your responsiveness and responsibility, especially if some weeks have passed and you have not responded even after receiving several reminders. Prof icient and proactive editors are likely to unassign you soon after the deadline has passed or even before the due date (depending on the situation), and invite other reviewers if needed.

Maintain conf identiality

Do not share any information—by any means—related to the peer review of a manuscript you agreed to review, either pre- or post-publication, unless you have the consent of the editors. By agreeing to review a paper, you also agree to keep all the information conf idential, unless instructed otherwise. Note that some journals instruct to even delete all relevant f iles once you have completed a review, so read carefully the reviewing instructions of the journal. Do not reveal any information to your family, colleagues, friends,supervisors, or students because it is considered a breach of conf identiality ( https:// publi catio nethi cs. org/ revie wer- conf i denti ality- breach- discu ssion). While some reviewers may agree to review a paper and then ask their students or other lab members to make a preliminary review for their training, it is expected that they inform and have the consent of editors in advance. However, remember that you get no credits for your work. Instead, you and your supervisor (or any other senior colleague) can make use of formal co-review on the basis of a mutual understanding. Several journals of fer this option nowadays “to help early-career researchers gain experience in peer review while ensuring they get credit for the work they contribute” ( https:// www. stm- publi shing. com/iop- publi shing- launc hes- co- review- policy/).

Disclose conf licts

In addition to the conf licts of interests for authors (Agathokleous 2022), there are further conditions consisting conf lict of interest when it comes to reviewers (Charlton 2004;Gasparyan et al. 2013; John et al. 2019; Dhillon 2021). A good example summarizing these conditions can be seen in the online guidelines of the Journal of Systems and Software: “The following situations are considered conf licts and should be avoided:

• Co-authoring publications with at least one of the authors in the past three years

• Being colleagues within the same section/department or similar organizational unit in the past three years

• Supervising/having supervised the doctoral work of the author (s) or being supervised/having been supervised by the author(s)

• Receiving professional or personal benef it resulting from the review

• Having a personal relationship (e.g. family, close friend)with the author(s)

• Having a direct or indirect f inancial interest in the paper being reviewed

It is not considered a Conf lict of Interest if the reviewers have worked together with the authors in a collaborative project (e.g. EU or DARPA) or if they have co-organized an event (e.g., PC co-chairs)” ( https:// www. journ als. elsev ier. com/ journ al- of- syste ms- and- softw are/ polic ies/ conf l ictof- inter est- guide lines- for- revie wers). More information is provided by experts’ bodies, such as the ICMJE ( http:// www.icmje. org/) and the World Association of Medical Editors(WAME) (Ferris and Fletcher 2012).

Pursuit aretê

As explained in my previous paper (Agathokleous 2022),aretê is the ethical/moral excellence or supremacy (Yiaslas 2019). Keep this in mind while serving as a reviewer. Avoid any unethical or immoral practices. These include personal attacks to authors, criticisms at a personal level, and inappropriate language, including the use of slangs, insulting or vilif ication, or verbal irony. Science has been built on the spirit of aretê since the ancient times. We should respect that and maintain some level of moral supremacy. Your job as a reviewer is not to comment on the authors’ ability or criticize authors at a personal level. If you subjugate yourself to your emotions and succumb to such practices, the editor may need to edit your review report or even exclude your entire review report. Furthermore, you may succeed in f lagging yourself as an inappropriate reviewer for the journal. You are supposed to comment on the research itself, the quality of the paper, and its appropriateness for publication in the journal, therefore stick onto that.

In the pursuit of aretê, avoid to be seduced by your emotions. There is no doubt that intelligence, commonly indicated by the intelligence quotient (IQ), is a great asset for a researcher. However, intellectual ability is not everything,and you may sabotage your performance, reputation, and even career if you subtly undermine yourself by being driven by your emotions. These may be some of the reasons why emotional intelligence (EI) has received increased attention in the recent years (Akerjordet and Severinsson 2007; Drigas and Papoutsi 2018; O’Connor et al. 2019). EI ref lects “the ability to identify, understand, and use emotions positively to manage anxiety, communicate well, empathize, overcome issues, solve problems, and manage conf licts” (Drigas and Papoutsi 2018). Remember that neither editors nor authors are interested in your feelings. Write your critique based on evidence/facts, not based on feelings.

“Anybody can become angry—that is easy, but to be angry with the right person and to the right degree and at the right time and for the right purpose, and in the right way—that is not within everybody’s power and is not easy”,Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics.

As a general suggestion, however, if you are in such a mental state, sleep on the review report. Keep it in the “deep freeze” for several days (even one day can make a big dif ference) and return later to write your report.

Justify your comments

No matter what you claim or criticize, make sure to justify the reasons and provide evidence. For example, if you are commenting on some methodological bias, e.g. insuf ficient number of experimental units, do not simply say that the experimental design is f lawed or that there are insuf ficient replicates of the experimental unit. Instead, write the number of replicates and mention the page and/or line number where this can be traced in the manuscript. As an author, you hope to receive constructive comments from reviewers, indicating also where you can f ind relevant errors in the manuscript, to facilitate your revision. As a reviewer, remember to do the same and indicate the relevant manuscript’s line numbers for each specif ic comment you list. Furthermore, do not push authors to cite yours and your colleagues’ papers based on subjective non-scientif ic grounds. Coercive self-citation by peer-reviewers has widely occurred (Thombs et al. 2015;Van Noorden and Singh Chawla 2019; Wren et al. 2019),and it may be expected that relevant analytical tools for policing such practices will be developed in the future,perhaps with some relevant indexes publically associated with the researchers’ names. Instead, be objective and do this, if necessary, based on objective scientif ic grounds that will be clearly explained, e.g. if authors present some views or ideas as if they were their original ones whereas you or your colleagues have presented them f irst. As an additional example, if you claim that there is literature suggesting or showing something, references should be properly cited in your critique. Finally, if you criticize that the language is problematic, justify what kinds of problems you have found and provide a few examples.

Here, I also advice against commenting that authors should ask a native speaker to check their paper. Whether they will do this or subject it to professional editing it is their decision. It was brought into my attention that non-native reviewers sometimes criticize the language simply because manuscripts are authored by non-native speakers. For example, a non-native reviewer commented that a paper should be checked by a native speaker simply because English was not the native language of the authors, yet authors had subjected the manuscript to professional editing. The certif icate of proof-reading was made available to editors upon submission, and the reviewer was not aware of this. The English language of the manuscript was excellent, and the reviewer did not provide any example of linguistic error. Moreover, a dif ferent reviewer was English native speaker and found the language f ine. The review report of the non-native reviewer was written in very poor language, suggesting that the reviewer was likely incompetent to assess the text subjected to professional proof reading. Some other times the opposite occurs. Manuscripts authored by English native speakers contain (sloppy) errors but non-native speakers do not suggest proof-reading by colleagues or professional proofreaders. There are two types of errors: performance errors and competence errors. The former errors are not serious and can be made by native speakers too, when tired or hurried,whereas the latter errors are more serious and ref lect inadequate knowledge (Touchie 1986). Therefore, if an author is not English native speaker and his/her manuscript contains only performance errors, he/she should be treated in the same way as an English native speaker. My point here,however, is that you should refrain from discriminating or making stereotypical comments based on authors’ names or institutions. At the end, there should be nothing self-implied nowadays. Someone can have a non-English name and live in a non-English-speaking country but be an English native speaker. Of note, you do not know who might be English native speaker. Be objective, and make such comments only if you are certain and can provide at least some examples.However, do not f ill your review report with every single typo or formatting issue you f ind (Dhillon 2021)—you act as a reviewer, not as a proof-reader.

Your role is not to teach authors (and they are not your students)

As a reviewer, you are not expected to re-write authors’paper. It is their own paper, and is written with their style and personal nuance. Editors have not invited you to teach authors writing papers. Do not diatribe. Just do what you are asked to do: editors have called upon your expertise to comment on the scientif ic value, novelty, and originality of the research as well as the quality of the paper, and provide constructive suggestions wherever possible. You do not need to try impressing authors and editors with your knowledge and skills. If it helps to remember that nobody knows everything,I would draw your attention to the ancient Greek apothegm

Open the response letter by writing a general paragraph summarizing your main critique; this facilitates editors’work and shows how well you have understood the research and paper. Here is a good place to highlight whether there are major limitations or problems with the study design,research methods, statistical applications, results interpretations, and conclusions drawing. This will help the editor to create a better picture of whether the paper may be publishable following revision. Then, provide a detailed list of all your observations, comments, and suggestions, with specif ic references to the relevant place in the manuscript (i.e. mention line numbers). Recall that you should justify all your comments and avoid general comments with no any proof or justif ication.

Do not put yourself in a box

Be f lexible. As we said, no single practice applies to every situation. Each review report may be totally dif ferent than all the preceding ones. Some years ago I heard a colleague saying that a review report should be one-two brief paragraphs,maximum one page. Science has no such rules. It depends on the paper, but a meticulous review report can be some pages long. A perfectly written paper with no issues in its scholarly content would leave little space for criticism and suggestions, leading to relatively smaller reports. As a reviewer, I have authored review reports from as little as a dozen words(one-two brief paragraphs) to as large as over 2,000 words.Face each paper as an individually specif ic case, and try to do a good job—be responsible.

Do not succumb to “two-face policy”

I call “two-face policy” the phenomenon where a reviewer’s recommendation or conf idential comment to editor does not match the comments to authors. This phenomenon appears sometimes and does not represent a good image for a reviewer in my view. I recommend against this practice.In general, conf idential comments to editors are needed only sometimes, such as to clarify that your review does not cover a specif ic methodology. Do not criticize authors at a personal level in the comments to editors. Transparency is important, and authors have the right to defend themselves by responding to any criticisms. Hence, if you want to input conf idential comments to editors, it is expected that they are in good alignment with the comments to authors.

Declarations

Conf lict of interest Any commercial name cited in this manuscript,e.g. of journal or software, is not for advertisement, and the author does not intend or encourage the use of their services. The views presented herein are those of the author and do not represent views of the editorial board of the journal, the editorial of fice of the journal, the journal itself, the publisher, or the author’s institution. E.A. is Associate Editor-in-Chief of this journal; however, he was not involved in the peer-review process of this manuscript. The author declares that there are no conf licts of interest.

杂志排行

Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Genome-wide identif ication and cold stress-induced expression analysis of the CBF gene family in Liriodendron chinense

- Decay rate of Larix gmelinii coarse woody debris on burned patches in the Greater Khingan Mountains

- Characterizing conservative and protective needs of the aridland forests of Sudan

- Point-cloud segmentation of individual trees in complex natural forest scenes based on a trunk-growth method

- Accuracy of common stem volume formulae using terrestrial photogrammetric point clouds: a case study with savanna trees in Benin

- Appropriate search techniques to estimate Weibull function parameters in a Pinus spp. plantation