Assessment on India’s involvement and capacity-building in Arctic Science

2021-04-10NikhilPAREEK

Nikhil PAREEK

• Article •

Assessment on India’s involvement and capacity-building in Arctic Science

Nikhil PAREEK

Department of Defense and National Security Studies, Panjab University, Chandigarh 160014, India

India became an observer in Arctic Council in 2013 and has three research stations operational in the poles, including “Maitri” commissioned in 1989 and “Bharati” commissioned in 2012 at Antarctic and “Himadri” at Arctic. Though the Government of India has consistently been extending full support to the research endeavours yet the same is bogged by inadequate research output, lack of dedicated polar research vessel and other bureaucratic bottlenecks. A massive void in the Indian scientific pursuits is that India does not possess a polar research vessel or an icebreaker and has to rely on chartered vessels, seriously limiting its research timeframe as well as huge economic drain and thus compromising the scientific research. This cleft in the professed research narrative despite having a physical presence for over 3 decades in the polar regions and the proposal for acquisition of a polar research vessel having been approved in June 2010 yet the same is yet to be operationalised which is seriously impinging the scientific research as well as the professed commitment to Arctic research. Recently, India has released its draft Arctic Policy and had sought public comments thereon till 26 January 21 before its finalisation. India’s draft policy reiterates the oft stated goals of scientific research, connectivity, global governance and international cooperation, and human development with emphasis on Indian human resource pool. The inspiration of a delayed Indian policy on the High North appears to be the Chinese white paper of 2018. The scientific pursuits can propel the strategic engagement in the region to greater levels by extensive collaboration and cooperation with several other nations present there. Indian attempts so far have remained acutely short of the promise and India should build on its strengths for obtaining a leadership position in this strategically vital and economically lucrative region.

Arctic, India, MOSAiC, Polar Research Vessel (PRV), scientific research

1 Introduction

The polar regions, especially the Arctic are considered to be a key driver of the Earth’s climate and the functioning of the world’s oceans and they even impact the geographically distant regions in a major way. Since the Arctic region possesses unique characteristics, it nurtures the origin of several climatic processes and can serve as an early warning of the ensuing climatic changes. In recent times, there has been an accelerated ice melt in the Arctic which is leading to a phenomenal rise in sea levels threatening to inundate many coastal nations. The rapidly receding ice cover will open new opportunities in the coming years in sectors like oil and gas, fisheries, tourism, and transportation. The logical fallout of the receding ice cover ushers in the prospect of the opening of new sea routes, namely, North East Passage/Northern Sea Route (NEP/NSR), North West Passage (NWP), Trans Polar Route (TPR), and the Arctic Bridge (AB) route.

The Asian Observer states have prominently been participating in the Arctic discourse both within the framework of the Arctic Council as well by bilateral arrangements with Arctic nations by increased impetus on scientific and economic cooperation yet India’s efforts remain lukewarm, requiring earnest, focussed and persistent policy direction. The scholarly output and the polar scientific studies by Indian scientists in various fields like Climatology, Glaciology and Oceanography remain short of accolades and promise and thus fail to grab international attention. For a third world country though with expansive aspirations it is vital for India to let science assume a lead role in shaping its Arctic engagement policy and mould interstate relations with a view to have greater outreach and influence. India’s political leadership and diplomatic corps have for long proclaimed its role as a global leader/world Guru but commensurate stature on world stage has still not been achieved. There is plentiful role of science as a tool of diplomacy to build long lasting partnership with allies for mutual benefit which make up the components of science diplomacy. Thus in the present times of scientific and technological breakthroughs, the ties between science and foreign policy to advance the best national interests is advocated. Since science can trespasses the barriers beyond political, economic, and cultural differences it can be effectively employed by diplomats/scientists for greater good of their nations as well as humanity. Till now, the progress on scientific discourse and science diplomacy has been subdued and India should make up for its lack of financial muscle and strategic calculations by steadfastly honing its scientific endeavours. India needs to enhance its investment in scientific research and innovation (Nayak, 2019).

2 National requirement

There is no gainsaying that when the Ottawa Declaration was signed in 1996, the signatories would not have fathomed that soon far-away countries like India, Singapore, Republic of Korea etc. would vie for a permanent berth in the Arctic Council. Unlike the European countries like France, the Netherlands and UK, which were granted observer status due to their existing memberships of the Arctic Environment Protection Strategy (AEPS), the Asian interest in the Arctic was necessitated due to commercial promise in Arctic exploration, resource exploitation and scientific discovery. The Arctic offers exploration in the quest for scientific knowledge and expertise coupled with the geopolitical manoeuvring to maximise the strategic strongholds in spheres like natural resources, regional governance and international influence. In the year 2007, one-time observer status in the Arctic Council was given to China and Republic of Korea, first among the Asian countries. In the same year, India which had signed the Spitsbergen Treaty in 1920 as a British dominion launched its first scientific expedition to the Arctic Ocean, and the following year, a research base named “Himadri” was inaugurated at the International Arctic Research Base at Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard, Norway. The Indian application for pursuing its research interests was based on the principle of freedom of scientific research and non-discrimination in conducting scientific pursuits that applied to the signatories of the Spitsbergen Treaty. India also cited its long polar research experience in Antarctica since 1983 as a basis to enlarge its scientific endeavours in the Arctic.

Later in May 2013, India was accorded the observer status along with four other Asian states namely China, Singapore, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. When India became an observer in Arctic Council, it had three research stations operational in the poles, including “Maitri” commissioned in 1989 and “Bharati” commissioned in 2012 at the Antarctic and “Himadri” at the Arctic.

After being granted the observer status, India had listed its “interests in the Arctic region as scientific, environmental, commercial as well as strategic” (Ministry of External Affairs, 2013). As per the initial Indian statement, after being accepted as an Observer, it had claimed that it will carry out studies in disciplines like Glaciology, Atmospheric sciences & Biological sciences. (Ministry of External Affairs, 2013). In the 2018 Observers’ Review Report submitted by India to the Arctic Council it was cited that “the Arctic Region is of special importance to India due to its critical role in governing global climate, sea level, and biodiversity” (Arctic Council, 2016). India also claimed that “Polar scientific research is a national priority for India” (Arctic Council, 2016). The basis for Indian scientific research in polar regions stems from having a research presence in the Antarctic since 1983 and wanting to replicate the model in the Arctic. For a third world developing country like India, the issue of the rapid Arctic ice melt and resultant changes in climate is compounded by having a burgeoning population and frequent environmental disasters disrupting lives and livelihoods. As per the official view of the Indian government, one of the chief reasons to pursue scientific research in the Arctic is “to study the hypothesized teleconnections between the Arctic climate and the Indian monsoon by analyzing the sediment and ice core records from the Arctic glaciers and the Arctic Ocean” (Ministry of External Affairs, 2013). Polar research is characterised by a high degree of interdisciplinary fields, the requirement of sophisticated infrastructure and logistic support, and international cooperation. Polar observatories are of crucial importance for the detection and analysis of changes occurring in the polar regions and are the bases for modelling of future scenarios. Research in the Arctic is being undertaken by countries and organisations to understand the transforming global climate system and its impact on respective populations and the environment. Thus the streams of science being studied in the Arctic encompasses multidisciplinary fields like biology, oceanography, geosciences, physics, space sciences, environmental sciences, astronomy, socio-economic sciences and humanities, and so on.

Though India has cited its research experience in the Antarctic as the basis of its scientific engagement in the Arctic, yet a comprehensive study of the bipolar comparisons of climatic conditions and distribution patterns of species is yet to be published. Likewise, India is yet to release any document/strategy on economic fallouts of a changing Arctic as well as resultant ramifications on health, climate change, and impact on indigenous communities. India relies on scientific cooperation with Norway to fulfill its requirements of scientific laboratory/observatory however the inter-disciplinary coordination as well as output remains scant. To further the scientific cooperation, the Indian Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES) funds PhD students at the Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI) and there is yet another Norwegian grant supporting Indian students at the University Centre in Svalbard.

The National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR) is mandated to carry out India’s research activities in the polar regions and Southern Ocean realms. The NCPOR functions under the MoES as an autonomous organisation heralding Indian research at Poles.

3 Rationality of national Arctic program

Ny-Ålesund (78º55′N, 11º56′E), a settlement situated on the shore of Kongsfjorden, has developed into an international research platform, with stations from 11 nations (China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Korea, Norway, Russia, Sweden, UK) and many visiting international researchers (Alfred Wegener Institut, 2008). Indian research in the Arctic has focussed primarily on atmospheric studies/meteorology, geosciences and environmental sciences. Since establishment of the Himadri research station, Indian research has hinged on obtaining geophysical/biological/chemical attributes around Kongs- fjorden alone and data on other vital areas like Central Arctic Ocean, Hornsund Fjord, Krossfjorden etc. are still not being adequately studied. This is partly due to the fact that India does not possess a polar research vessel (PRV) or an icebreaker and thus the research remains confined to the limited places.

Kongsfjorden is a glacial fjord without sills on the West Spitsbergen coast and has stood out as the focus area of Indian Arctic studies. India’s first multi-sensor mooring was deployed on 23 July 2014 at 78º56'N and 12ºE in the inner Kongsfjorden where the depth is ~180 m (NCPOR, 2015a). Since the multi sensor mooring has been deployed at Kongsfjorden and India lacks the wherewithal to probe the Central Arctic Ocean and other areas, its research remains lopsided. Kongsfjorden represents one of the best-studied Arctic fjord systems. However, research conducted to date has concentrated largely on small disciplinary projects, prompting the need for a higher level of integration of future research activities (Bischof et al., 2019).

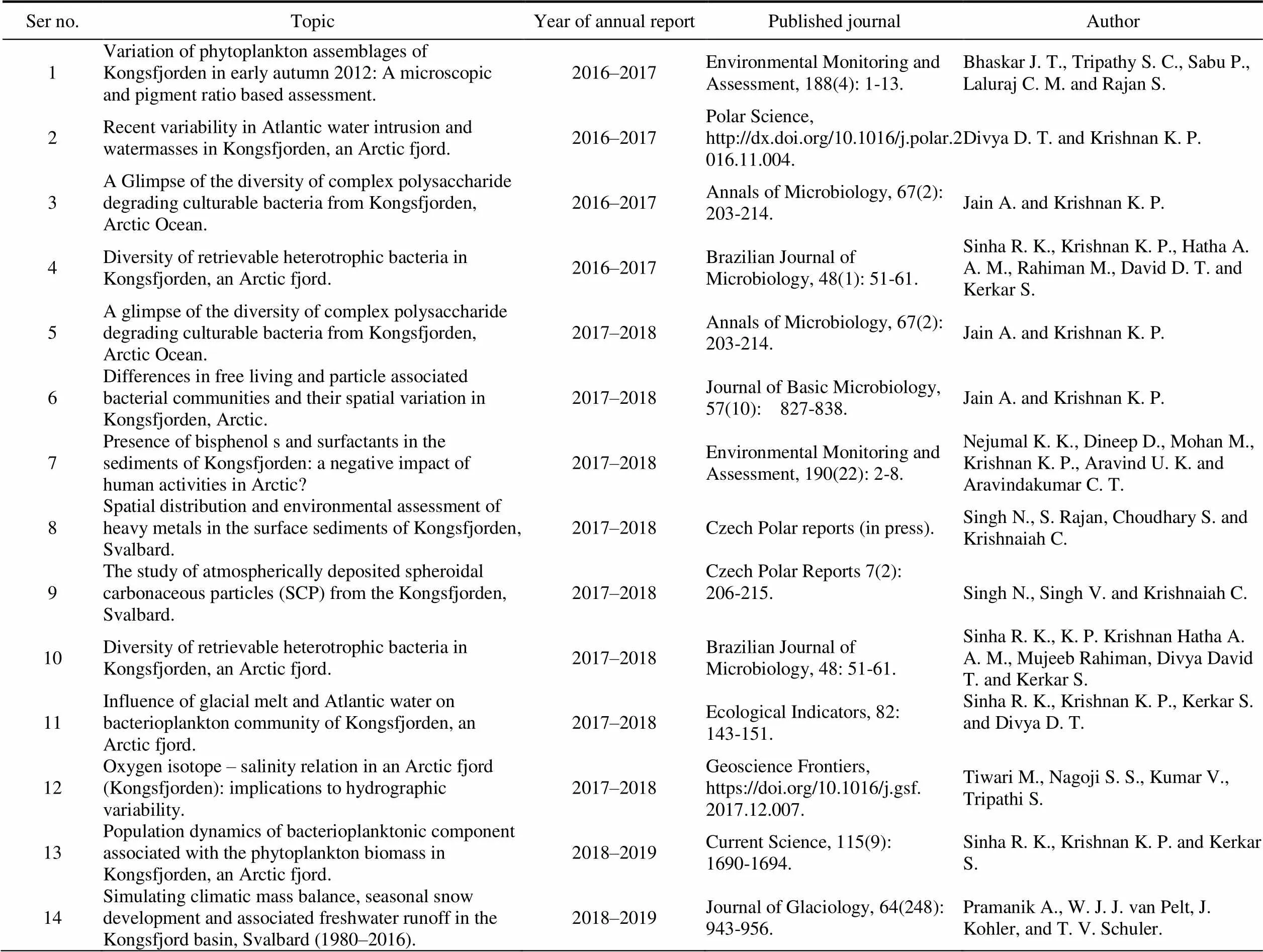

There is a significant amount of observations available from the Kongsfjorden area, including historical and recent databases on: oceanography of Svalbard waters (1905–), meteorology (1911–), contaminants (1988–), tide gauge measurements (1974–), hard-bottom benthos (1980–), seabirds (1988–), CTD-measurements (1993–), zooplankton (1995–), stable isotopes and lipids (1996–), ice concentration, snow and ice thickness (2003–, occasionally 1997–) and radionucleides as tracers of C-flux and mixing processes (1996–) (Alfred Wegener Institut, 2008). Since lots of information and data has already been documented and recorded, Indian research could have been diverted to explore novel avenues rather than duplication of mostly available research. With a view to clearly understand the global change and climate change induced processes the past history of the ecosystem should be described using long-term monitoring by utilising oceanographic data. Other research institutions like the Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI), The University Center in Svalbard (UNIS), Institute of Oceanology Polish Academy of Science (IOPAS), etc. collect ship-based data, which could have been requested by diplomatic leverages and analysed for effective research however India lags behind on his aspect too. The following table gives out the research topics and areas by Indian researchers on Kongsfjorden in the last three years. Since there are plethora of research teams operating around Kongsfjorden, it would have been beneficial for India to enter into collaborative arrangements and data sharing among the Arctic nations as well as Observer states that would have led to accurate, reliable information as well as reduce the duplication of efforts. Also, in the absence of a dedicated icebreaker India has to rely on chartered vessels for sending its research personnel to the Himadri station seriously limiting its research timeframe as well as causing huge economic drain on its meagre resources.

Most of the topics by Indian researchers have already been studied and documented by researchers from other countries; however the recourse to obtain such data by sharing and collaboration has not been explored.

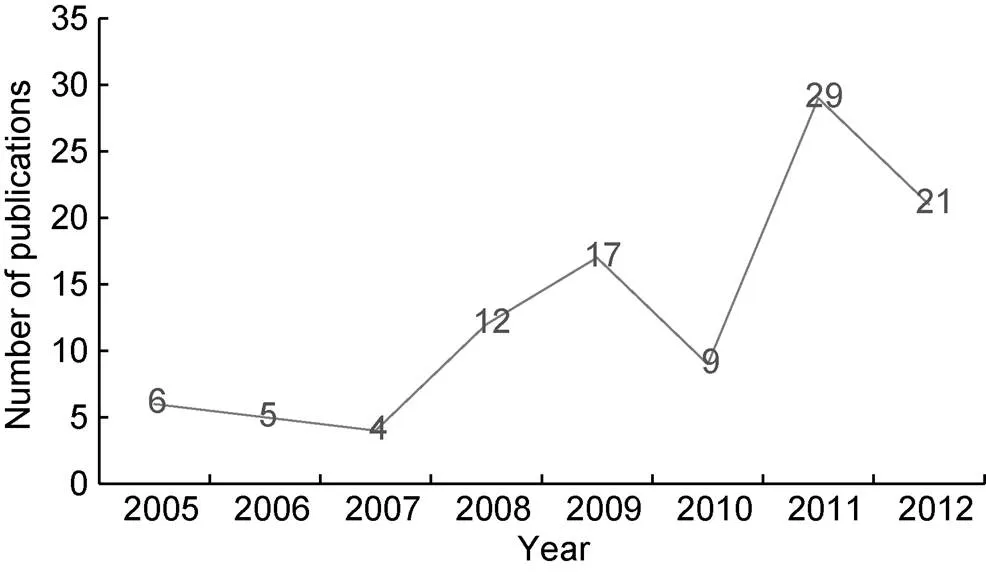

Though Indian polar research legacy boasts of over three and a half decades of experience, yet the Indian Scientific endeavours in the Arctic remain rather modest with minimal international collaboration. As per a report, 63.1% of the publications had Indian authors only and one-fourth of the articles were published in Indian Journals only (Stensdal, 2013). Figure 1 placed below shows that the published research by India falls acutely short of the promise of stated Indian claims.

4 Efficiency of budgeting/funding

The polar research and scientific diplomacy require a number of initiatives including the establishment of Arctic research facility/facilities, sending various scientific expeditions in diverse areas to measure and study the geophysical and other characteristics onboard PRVs and other engagements in science-related committees. Since India has established three research stations at the poles, there is a need to access these all around the year to obtain accurate scientific data. The need to have polar icebreaker ships to have access to these facilities, under challenging ice conditions is one of the foremost requirements to have credible research and to access research stations at will, to further the stated national scientific policy purpose. The requirement of a PRV is important as India has plans to rebuild “Maitri”, its research station in Antarctica, and make it impervious to its harsh environment for at least 25 years. The strategic importance of the Arctic region is growing exponentially and in the coming days, there will be increased economic activity as peak sea ice thins due to global warming and climate change.

Table 1 Research topics on Kongsfjorden (2016–2019)

Source: NCPOR, 2017, 2018, 2019a.

Figure 1 Arctic research publications with Indian authors, 2005–2012.

The cleft in the professed research narrative despite having a physical presence for over three decades in the polar regions and the proposal for acquisition of a PRV having been “approved in Jun 2010”(Ministry of Earth Sciences, 2015a) but the construction and operationalisation of the PRV remains a distant dream. This belated and nonchalant response is impinging on the scientific efforts and also manifesting in scanty Indian research of reputable standards.

As per the answer to a Parliamentary question, it was stated by the Minister of Earth Sciences that the approval of PRV was approved at an estimated cost of 4900×10INR (nearly 107×10USD ) in June 2010 and the timelines for implementation thereof were as under:

(1) Finalization of the design specifications including the onboard laboratory instrumentation and infrastructure.

(2) Floating of a Global Tender for the construction and identification of the Shipyard.

(3) Finalization of the Agreement with the identified yard.

(4) Initiation of construction of the PRV (2012–2013).

(5) Construction and sea trials (2013–2015).

(6) Commissioning of the vessel (2015–2016)(Ministry of Earth Sciences, 2015a).

In 2014, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs approved the Revised Cost Estimates for procurement of the PRV at the revised cost of 10510×10INR (nearly 178×10USD) (Ministry of Earth Sciences, 2015b). Then in 2015, Indian Government decided to construct the PRV at a shipyard in Spain (Tejonmayam, 2015) yet this project too later fell through due to escalated costs and Indian government’s focus on its “Make in India” initiative, though India did not have anexperiencein the construction of ice-class vessels and PRVs.

After much delay and procrastination, the Global Expression of Interest (EOI) for providing competent experienced workforce in supporting the construction of PRV was released by Goa Shipyard Limited (GSL) on 30 April 2019 (Goa Shipyard Limited, 2019). Going by the historical indicators of project execution by India, there are at least a full three to four years before the PRV is constructed and considered to be seaworthy, provided there are no further glitches and delays.

The Indian inexperience in construction of icebreakers and PRVs, which are required to wade through one and a half metres of ice, is likely to cause further impediments in the construction of vessel as India wants to steer the production despite its lack of experience in the fabrication of ice-class vessels. The efficacy of the indigenously constructed vessel meeting the required standards in the unpredictable polar climatic conditions will be learnt after extensive sea trials and handling in the tough polar conditions. The Expression of Interest document has listed the requirement ‘for providing experienced workforce in construction of PRV (Goa Shipyard Limited, 2019) which clearly conveys that India intends to fabricate the vessel rather than enter into a supply cum maintenance contract with any reputed global shipbuilder. The latter arrangement could have also provided for technological upgrades from time to time and repairs/overhauls if contracted.

It has been noticed that retrofit and lay-up repairs for NCPOR’s ORV (Ocean Research Vessel) Sagar Kanya have been carried out at Srilanka in the past. The retrofit in 2014 was carried out at Colombo Dockyard Plc (Colombo Dockyard PLC, 2014) and likewise some repair work was carried out in 2017 (NCPOR, 2018). These instances point out that the repairs for even non-ice class research vessels is being undertaken outside India and not being contracted to government organisations like Goa Shipyards Ltd, which though has been assigned the responsibility of fabrication of the maiden Indian Icebreaker. Colombo Dockyard had even been undertaking overhauls of ships of Shipping Corporation of India (SCI), Indian Navy and other Indian companies. The rationale for indigenous fabrication of ice class vessel with meagre shipbuilding credentials and experience may later prove to be both a financially unwise decision as well as missing on the opportunity to build strategic partnerships by way of this project.

5 Ratio of relative investments and output

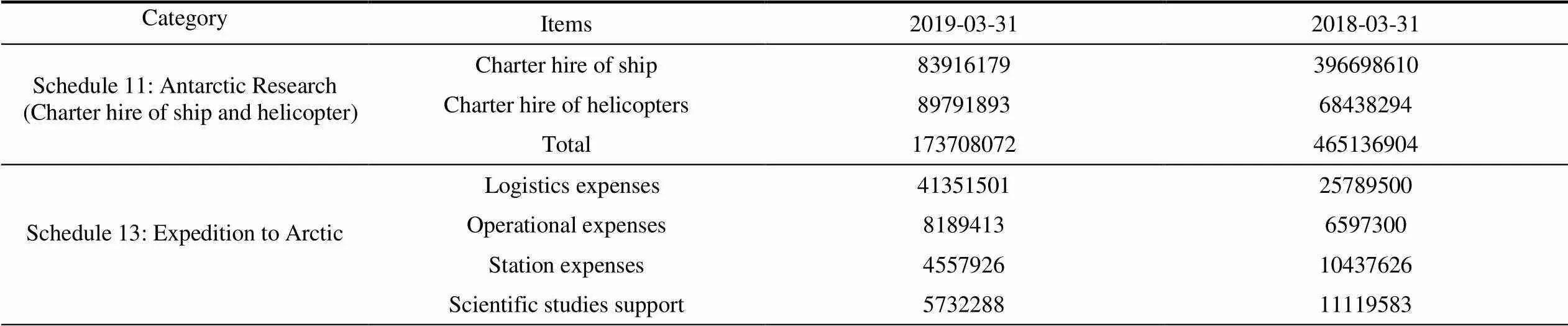

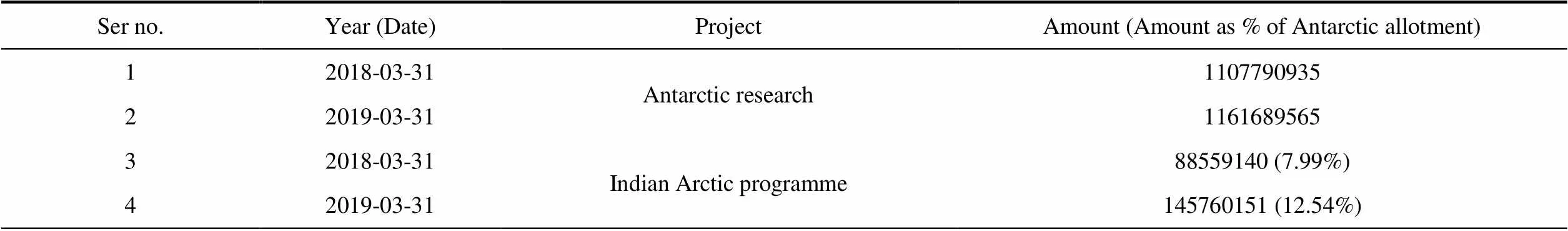

Though the quantum of funds expended by the NCPOR for the previous years in chartering various vessels for the sustenance of its research stations in the Arctic is not given out explicitly in the annual reports (NCPOR, 2018), yet it can be seen from Table 2 below that the expenses on charter hire of ships alone far exceed the Station, Scientific Studies and Operational expenses put together.

On perusal of the above table, it is clear the charter hiring expenses of ships and helicopters in respect of the Arctic are neither included nor provided separately in the Annual reports yet, it is abundantly clear that sizeable sums of money are being spent on the hiring of vessels so as to keep the polar research stations working. A connected issue is that the ice-class vessels cannot be employed in other oceanographic research work. As per the acknowledgment by the Ministry of Earth Sciences, “So far the expeditions have been launched using cargo vessels with the result that no significant marine scientific experiments could be launched and owning our own ice breaker vessel will reduce India’s dependence on foreign vessels and give us freedom of planning diverse scientific programs” (Ministry of Earth Sciences, 2018a)

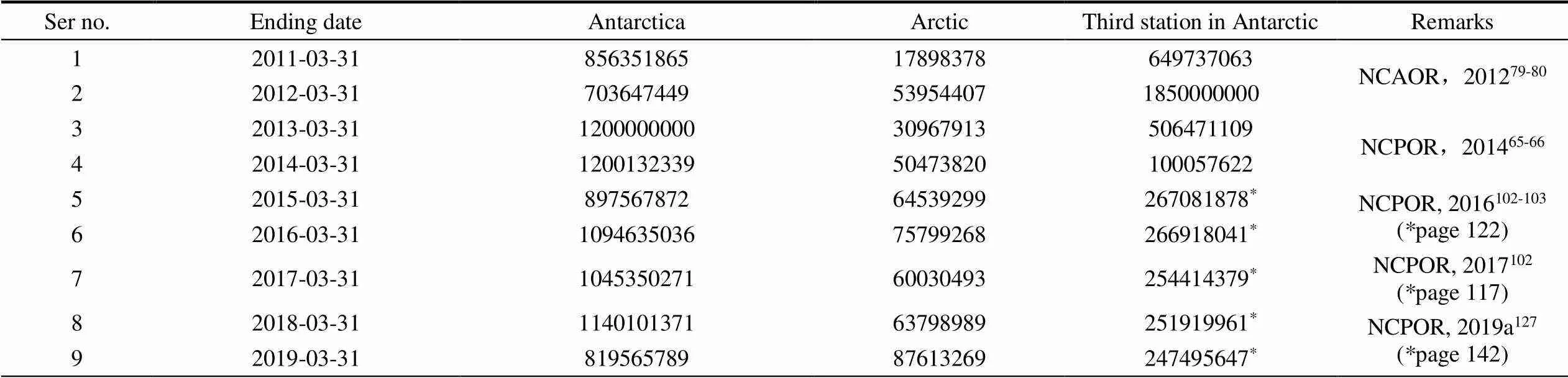

Table 2 Polar expenditure (Currency: INR/Rupees)

Source: NCPOR, 2019a, page 143, 145.

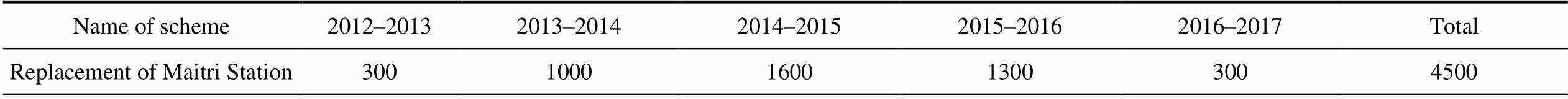

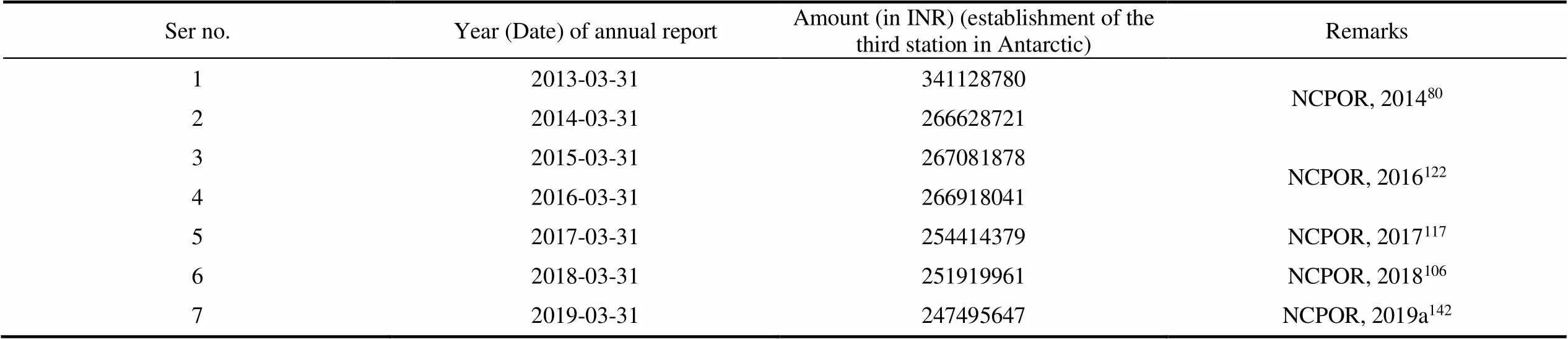

India also plans to rebuild its Maitri station at a more favourable and environmentally friendly location satisfying the Antarctic Protocols. This project has been termed as the third station in Antarctica and sizeable amounts are being earmarked for the same. However, there appears to be a major variance between figures quoted by MoES (Ministry of Earth Sciences, 2015c) and those placed in NCPOR Annual Reports. Table 3 shows the budgeting/estimation of funds by the MoES, published and posted on its official website. Table 4 shows the outlay on establishment of the hird Antarctic station (Funds shown as annual depreciation) as per NCPOR Annual Reports.

The annual accounts of NCPOR are being audited by an independent Chartered Accountant and the rationale of writing off such huge amounts as depreciation even before the commissioning of the station is left for accounting professionals to comment, however there appears to be certain omissions in the allotment and accounting of the funds. As per NCPOR Annual Report 2018–2019, the funds for establishment of the third station in Antarctica are INR 1077013169 and INR 825093208 for the years 2018 and 2019 respectively. Surprisingly, there also is a disconnection between the proposed earmarking of funds by the Ministry of Earth Sciences and the organisation implementing the same.

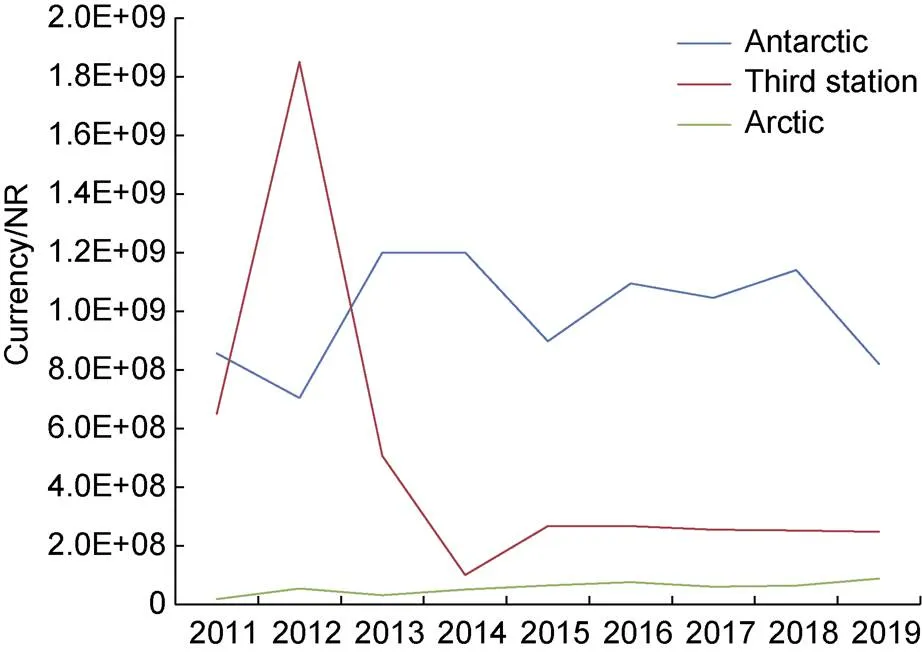

It is also evident by the fund allotment by the Indian government that the Antarctic scientific activities assume much greater focus than the Arctic efforts. Table 5 and Figure 2 placed below clearly depict that the Indian government lays focus on the Antarctic research and the monetary outgo far exceeds that of the Arctic region.

There are huge geostrategic, political and economic payoffs in the Arctic as compared to the Antarctic, yet the latter still seems to be the focal point of India’s polar research. The Arctic has gained greater notice and traction in world affairs due to its impact on climate change and role in shaping regional politics and it is vital for India to give greater priority to the affairs of the North. Table 6 placed below shows the variance in allotment of funds between the various projects.

Table 3 Budget requirement for replacement of Maitri Station

Currency: Million Rupees (INR). Source: Ministry of Earth Sciences, 2015c.

Table 4 Establishment of the third station in Antarctic

Table 5 Resource allotment for polar programmes

Notes: (1) All figures have been taken from Schedule 3: Earmarked funds except * which have been taken from Schedule 7: Grant-in aid;(2) All figures in Rupees/INR.

Figure 2 Resource allotment for polar programmes.

6 Project implementation

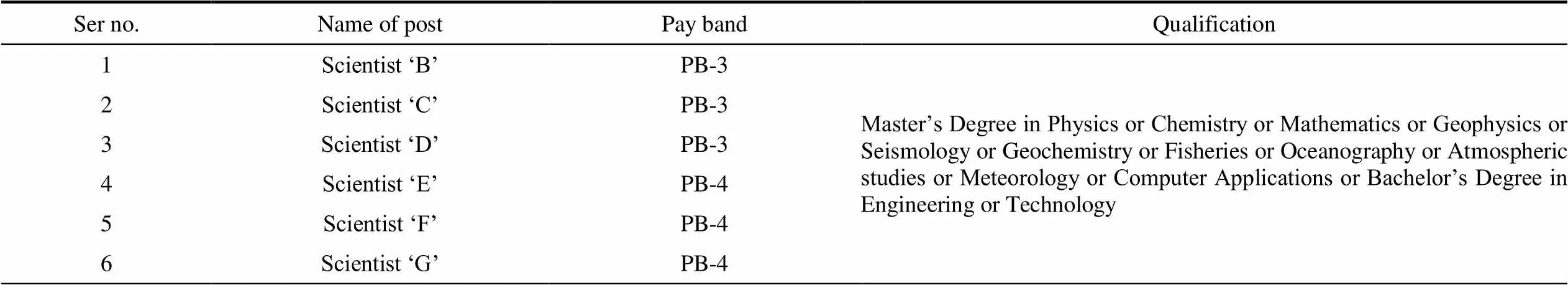

As per the Gazette notification by the Government of India/(Ministry of Earth Sciences, 2012) and Scientists Recruitment Rules, 2011 (National Institute of Ocean Technology, 2011) scientists are recruited in six categories in the Ministry of Earth Sciences. Table 7 given below shows these categories of scientists in the MoES.

The staff strength of NCPOR as given in the Annual Reports points out that the number of sanctioned personnel is arrived at keeping in mind the expertise required in assorted scientific fields. Table 8 below gives out the filled vacancies as on 31 Mar 2019.

Table 6 Funds allotted to various programmes (2018 and 2019)

Source: NCPOR, 2019a.

Table 7 Scientists in MoES

Source: National Institute of Ocean Technology, 2011.

Table 8 Staff of NCPOR as on 31 Mar 2019

Source: NCPOR, 2019a.

Keeping in mind the expanding scope of research and required support staff the NCPOR staff was enhanced from 38 scientists to 45 and the other staff from 35 to 43 since 2013 (NCPOR, 2014) which is substantial at increase of around 20% and should have led to greater and synergised research in specific specialised domains. Since there is no independent scientific audit of the NCPOR work the quality of scientific output can be commented by scientific bodies/institutions.

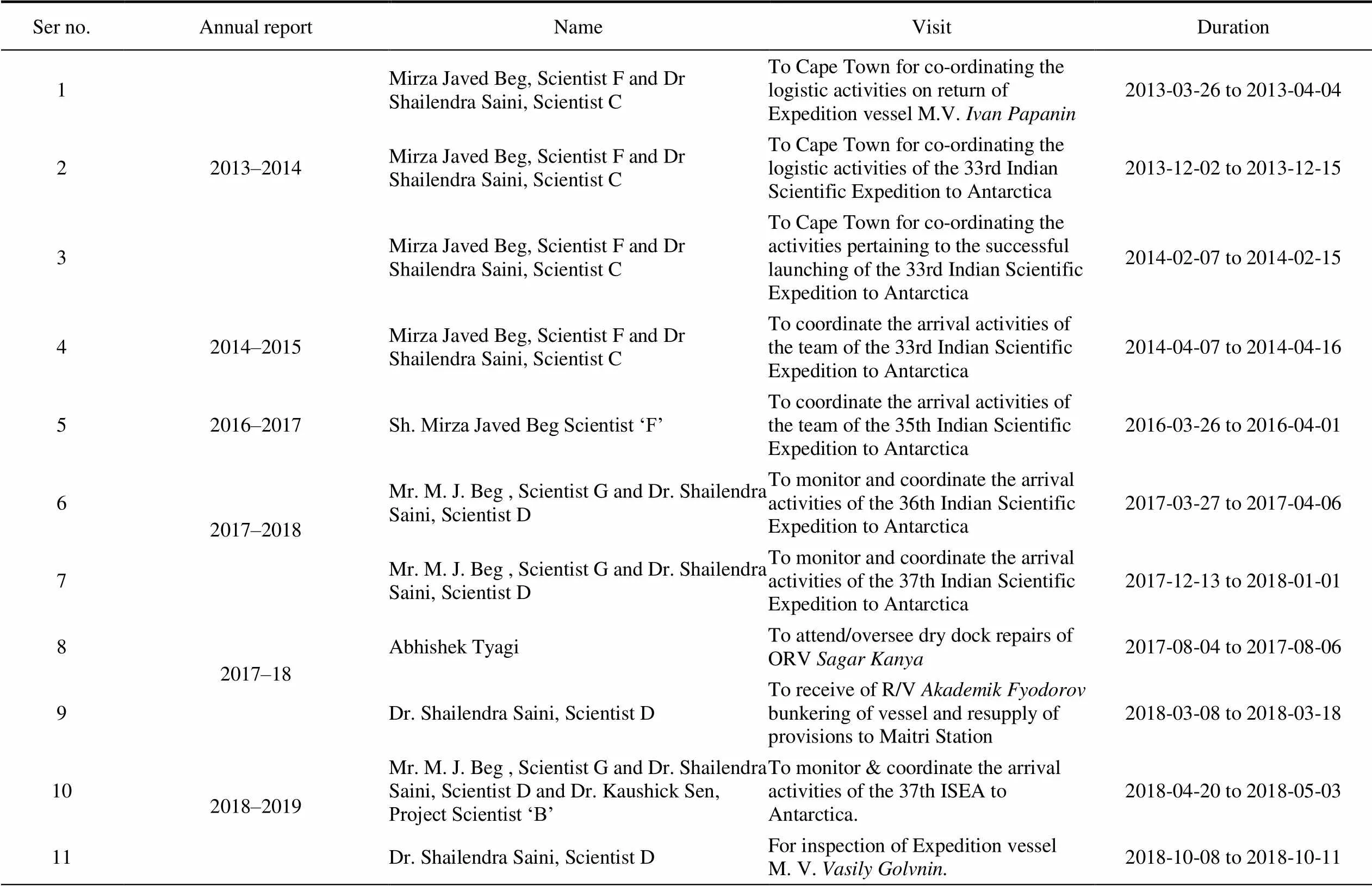

As per the data placed on NCPOR Annual Reports, it is seen that scientists from the above mentioned categories are regularly being sent for inspection of research vessels and to coordinate the logistic activities of Indian scientific expeditions to the polar regions. This clearly shows acute apathy to professionalism and assigning of general administrative tasks like coordinating the logistics arrangements without considering the expertise and experience of scientists in their specific domains. The job of ascertaining and certifying vessels should be suitably and effectively done by experienced naval/shipping engineering personnel, yet the fixation with bureaucratic red-tape and the lack of inter-ministerial cooperation is evident. Table 9 below shows the instances where scientists have been assigned such responsibilities.

Table 9 Scientists assigned on ship inspection/administrative tasks

Source: NCPOR, 2014, 2015c, 2017, 2018, 2019a.

As per data available on open domain, it is learnt that Mirza Javed Beg is a geologist by profession (NCPOR, 2019b) and Dr. Shailendra Saini is M Sc (Electronics) (NCPOR, 2015b) and don’t possess the requisite skills to test and certify the seaworthiness of vessels on parameters like hull inspection, maritime regulations, IMO Conventions (SOLAS, MARPOL), navigational audits and importantly safety while operating in polar conditions.

Importantly, Shipping Corporation of India (SCI) which manages the oceanographic and coastal vessels on behalf of government agencies/departments including NCPOR (The Shipping Corporation of India Limited, 2019) is not being given such responsibility which clearly portrays that the view being adopted is myopic and there is lack of coordination between the government departments which is impinging the core area of scientific research as trained personnel are being given tasks outside their core competencies. It is also vital to point out that the Directorate General of Shipping; Government of India has also released its Guidelines for Advanced Training Course for ships operating in Polar Waters (Directorate General of shipping, 2018) which caters to training and certification requirements for Masters, Chief Mates and Officers in Charge of navigational watch on ships operating in Polar waters. The recourse to aforesaid delegation of scientists on engineering/administrative tasks projects a sorrow state showing the lack of any inter-ministerial interaction and as well as lax oversight and supervision by senior functionaries. The inadequacy of management both at NCPOR as well as at Ministry level especially MoES and Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) levels is also discerned which may be one of the reasons of inadequate Indian scientific pursuits at the polar regions. The callousness in allocation of such work leads to not only inadequate inspection of vessels but digresses the scientists from the core area of polar research work. Incidentally, as per the NCPOR Annual Report 2018–2019 page 25 ‘MVwas stranded in sea ice for nearly 27 days’ post such inspection by the Dr S Saini, NCPOR scientist (NCPOR, 2019a).

An underlying incentivisation of the scientists by affording government funded foreign trips at the cost of operational and research output points to the unprofessional conduct and bureaucratic appeasement. There is no gainsaying that the core expertise of these scientists is being denuded by assigning them on such assignments.

7 Involvement in the international community of scientists

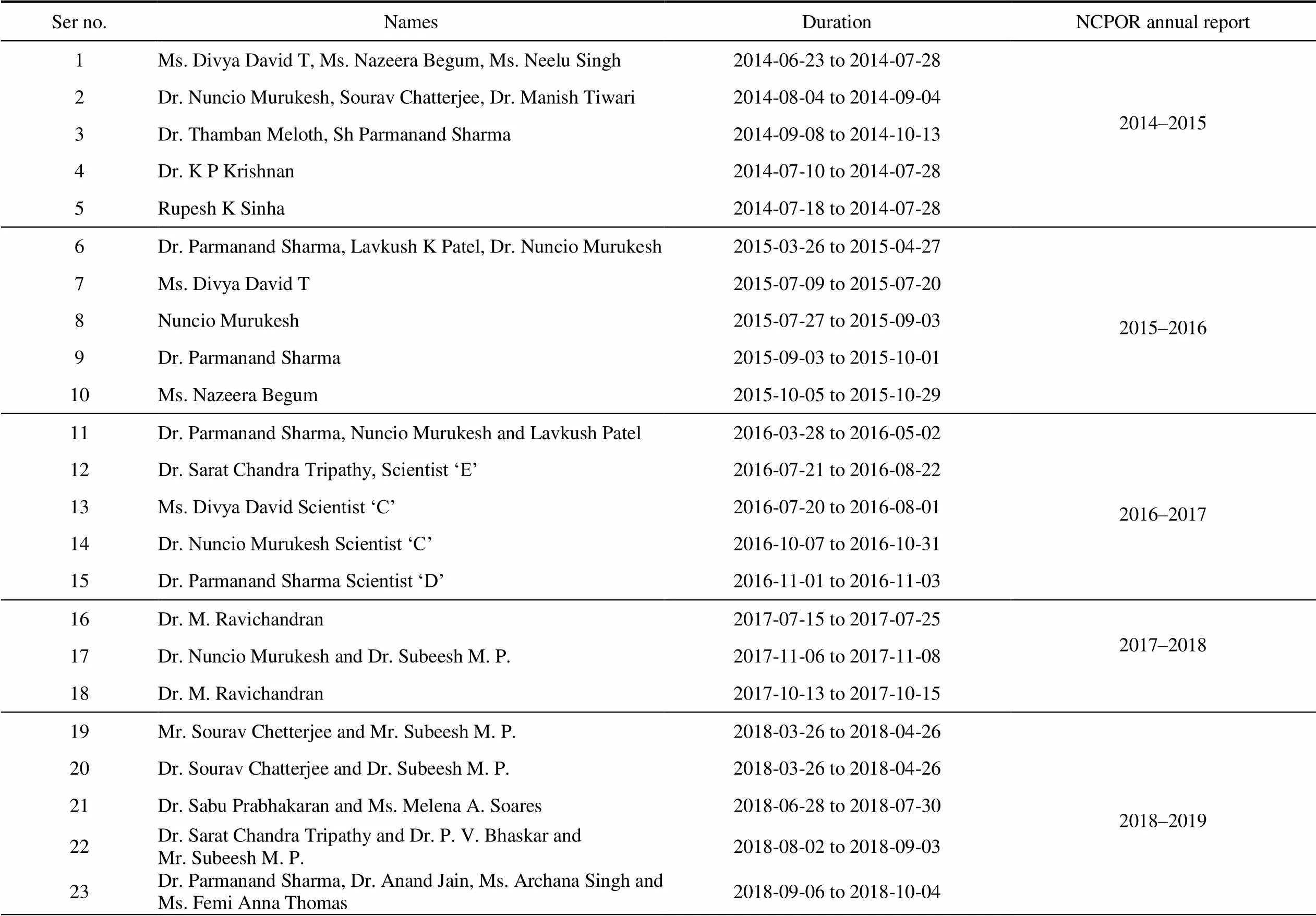

Based on the study of NCPOR Annual Reports another interesting yet worrying attribute which has been noticed is that the duration of stay of various research personnel is generally limited to one month or close to it. Also generally there is no researcher stationed at Himadri research station between the months of October to March hence the comparative study of the biological/chemical specimens may not be providing the comprehensive account. As per layman’s understanding, it is assessed that the spread, distribution and propagation of living specimens/species is dynamic and would be changing according to the season. For an accurate and precise assessment of specimens it is vital to study theses throughout the fall and winter and through spring and summer as well.

Another distressing feature noticed by study of the Annual Reports is that the size of Indian delegation to Antarctica expeditions is much larger and thereby having scientists of various specialisations though the Arctic expeditions are being sent at skeletal form. Table 10 below gives out the duration of visit of various scientists at the Arctic in the last five years.

Table 10 NCPOR Scientists at Himadri Station (2014–2019)

Source: NCPOR, 2014, 2015c, 2016, 2017, 2018.

It is observed that in year 2012–2013, 14 scientists were sent on field assignment to Arctic (NCPOR, 2013) and the fields of study of particular scientists like glaciology (4), snow chemistry (1), biodiversity in the Arctic (1), Kongsfjorden monitoring (6), Arctic precipitation (2) is explicitly given out. The later reports have gradually discontinued giving out the fields of study of NCPOR personnel as also the concerned area of specialisation.

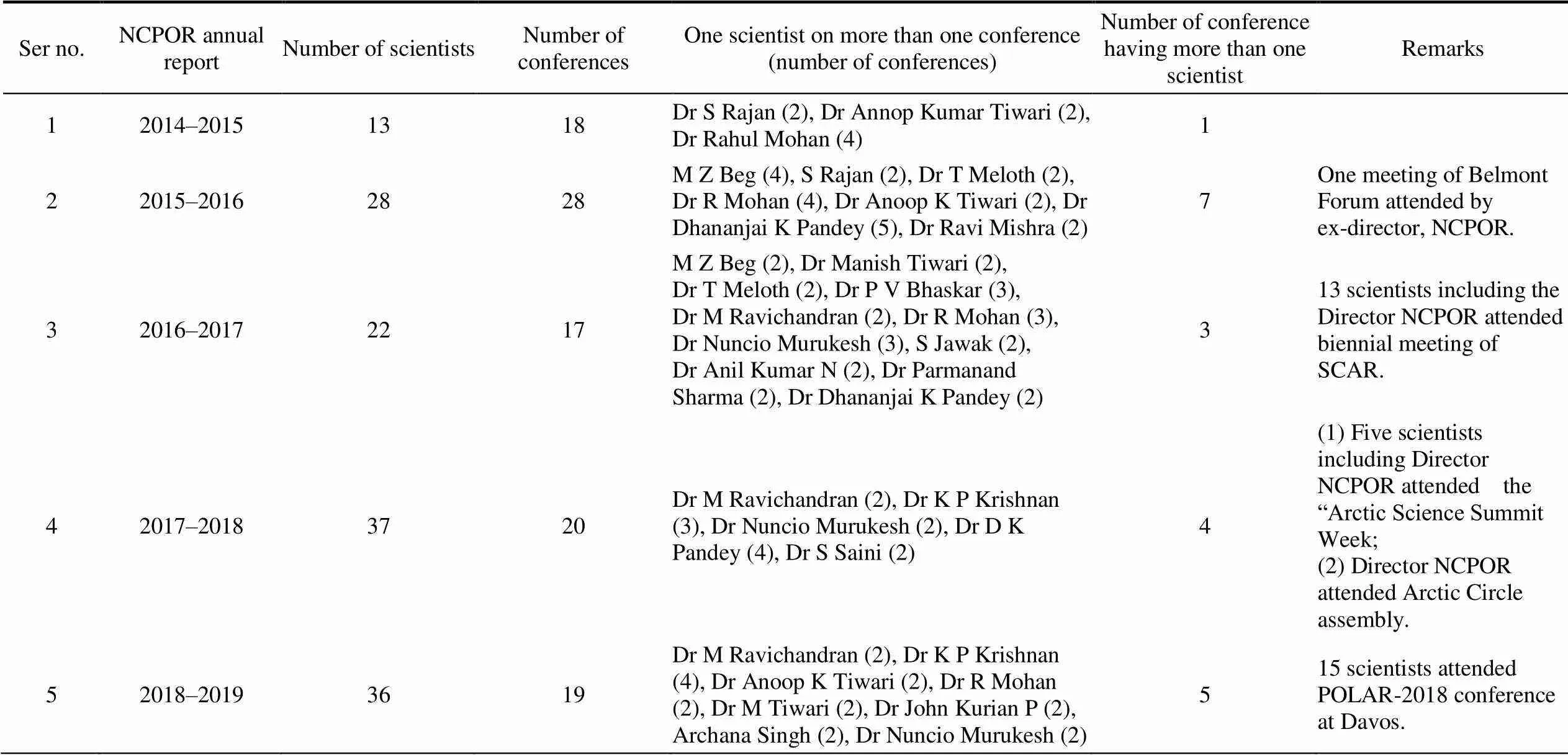

In contrast to sending full complement of research teams to “Himadri” to progress the scientific studies in multiple disciplines, it is noticed that large number of scientists are being sent to attend meetings, conferences and seminars. As is covered elsewhere, on one hand the Indian government is citing lack of financial resources while on the other it is seen that a substantially large delegations are being sent to diverse places for attending conferences. Though the latter provide easy access to research activities and assists in building networks with other academics and experts yet India could advantageously employ the assistance provided by Norway in utilising its research infrastructure and build robust partnerships with other Observer states at Ny-Ålesund itself. Table 11 below gives out the visits by NCPOR scientists to various meetings/ conferences.

Table 11 Conferences/seminars attended by NCPOR scientists (2014–2019)

Source: NCPOR, 2015c, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019a.

8 Participation in Arctic governance and international cooperation

In the formal structure of the Arctic Council, the Ministerial Meetings are hierarchically followed by the Senior Arctic Officials (SAO) meetings where major decisions are taken. The participation by non-Arctic states and observers is thus confined to the Working Group (WG) meetings which are conducted in less formal structures, unlike the Ministerial and SAO meetings which have diplomatic settings.

Each member state is represented by a Senior Arctic Official (SAO), who is usually drawn from that country’s foreign ministry. The lacklustre Indian scientific participation even at the Working Group (WG) level is due to the restricted domain of expertise, limited to the areas of the WGs. Though the Ministerial and SAO meetings are supposed to be attended by the diplomatic officers, India has been seen to be sending its scientists which denudes the strategic and geopolitical significance and worryingly projects irreverence to Arctic council structures.

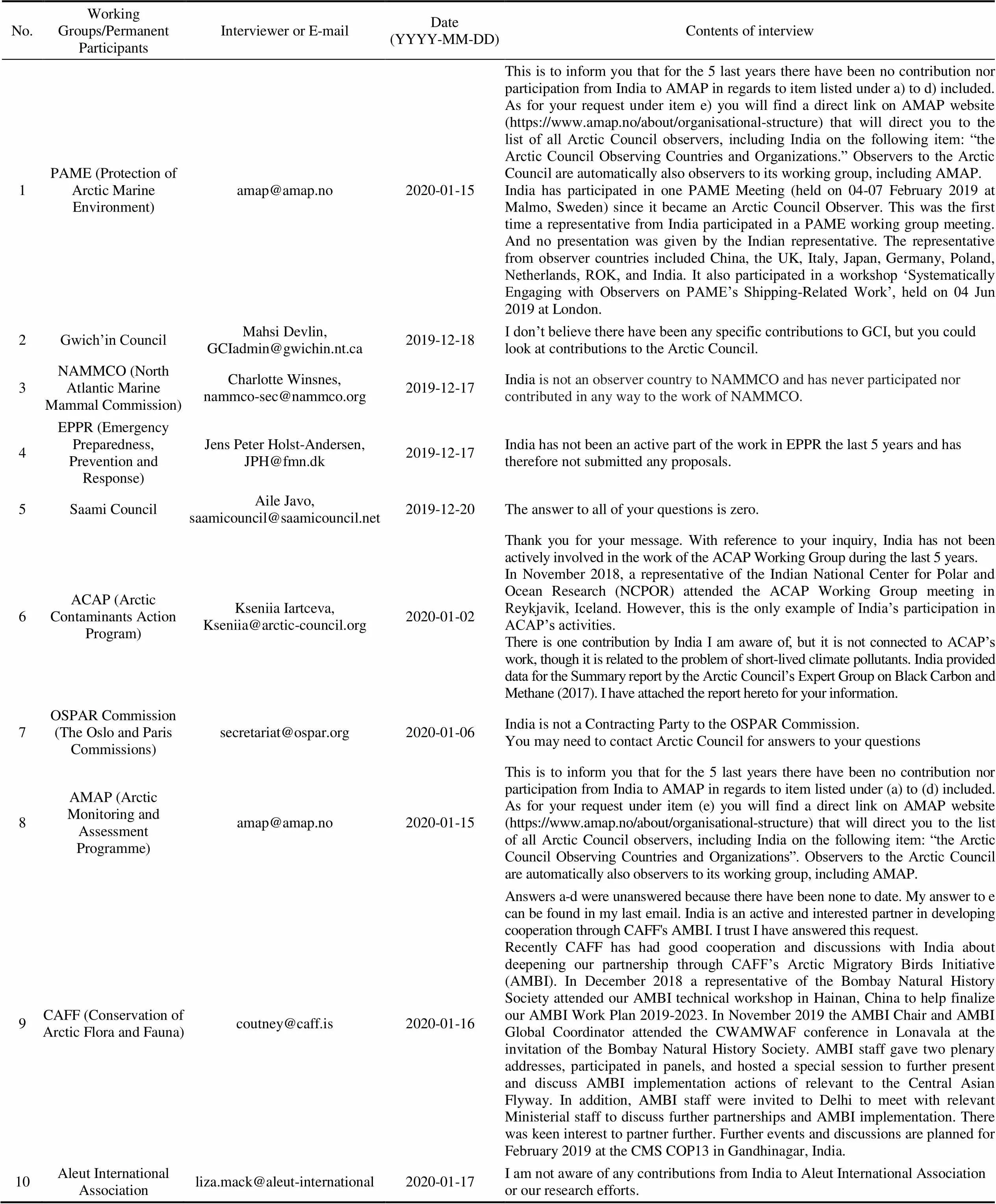

The Arctic Circle meetings bring together governments, organisations, corporations, universities, think tanks, environmental associations, indigenous communities, concerned citizens, and others interested in the development of the Arctic and its consequences for the future of the globe but is a non-scientific meeting. Though there are political undercurrents in the meetings yet economic agenda,climate change, sustainable development, etc are more hyped. As can be seen from Table 12 that India sent its Director NCPOR to attend the annual Arctic Circle assembly in 2017 but no one was sent in 2019. In the annual reports of NCPOR it has been noticed that the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCM) have regularly been attended by the Indian scientists. The motivations for agreeing an Antarctic Treaty were political not scientific, in essence calling a truce on territorial dispute and preventing the militarization of Antarctica (Scully, 2011). India appears to be taking a myopic view of Antarctica through a scientific prism only and thus losing out on the geopolitical leverage as a CP (Consultative Party). The emerging economies such as China, South Korea and India, along with a re-emerging Russia, are all interested in taking leading roles in shaping new international instruments that will better reflect their national interests. (Brady, 2013). Also when India’s observer status in Arctic Council was renewed in May 2019, Dr M Rajeevan, Secretary, MoES was present in Rovaniemi rather than any diplomatic/ foreign service representative which depicts the massive fissures in India’s approach to its engagement with Arctic Council and its Arctic involvement which is viewed from a scientific prism and not from the strategic/geopolitical perspective. Table 12 shows few instances when scientists were sent to attend diplomatic conferences.

There is also a variance between the pre-AC observer states and the new ones like India with the former having their established scientists entrenched in the WGs while the latter have no leverage in the WGs, too. The participation by India in AC meetings and with PPs/WGs has also been acutely deficient and thus few outcomes have been accomplished, so far. Email sent to Director NCPOR dated 19 Dec 19 seeking India’s participation in Arctic went unanswered. India’s Engagement with select Permanent Participants, Working Groups, NGOs of AC in the last five years obtained by way of personal communication/emails is reproduced as Appendix Table S1. The standard questions posed to these organisations were:

Table 12 NCPOR scientists attending diplomatic conferences

Source: NCPOR, 2015c, 2017, 2018.

(1) Proposals submitted, proposal accepted, outcomes;

(2) Funding assistance;

(3) Papers etc submitted which were accepted and published;

(4) Any citation/reward/acknowledgment of prolific scientific work by India;

(5) Any other information on India’s endeavours.

In September 2019, the largest Arctic science mission in history, Multidisciplinary Drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC) with the participation of 20 countries and hundreds of scientists had set off from Norway. The goal of the MOSAiC expedition is to take the closest look ever at the Arctic as the epicenter of global warming and to gain fundamental insights that are key to better understand global climate change. The scientists are aboard the German icebreaker Polarstern and will spend a year drifting through the Arctic Ocean – trapped in ice.Another ship on the expedition is the Russian research vessel, Akademik Fedorov. The primary question the MOSAiC scientists are asking: “What are the causes of diminishing Arctic ice? and what are the consequences? ”(Koenig, 2019). The focus of the expedition in the scientific domain is – Atmosphere, sea ice, Ocean, Ecosystem, and Biogeochemistry. Conspicuously, there is no participation from India in this expedition.

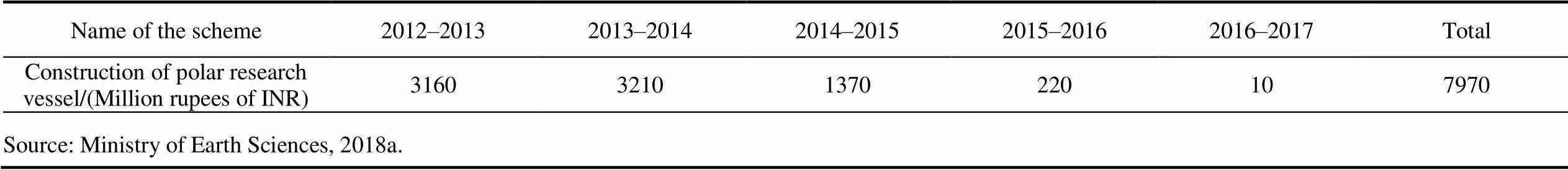

9 Implementation capability

Though as per a 2018 report of Indian Parliament upper House’s (Rajya Sabha) – 315th report noted that “the proposal for acquisition of PRV under the PACER program will be delayed due to paucity of funds” (Sabha, 2018). Yet as per data put on Ministry of Earth Sciences website, the budgeting for the PRV has been continuing since 2012–2013. The activities of MoES are carried out under the following five major programs (Ministry of Earth Sciences, 2018b): (1) Atmosphere and Climate Research – Modelling, Observing Systems and Services (ACROSS); (2) Ocean Services, Technology, Observations, Resources, Modelling and Science (OSTORMS); (3) Polar and Cryosphere Research (PACER); (4) Seismology and Geosciences (SAGE); (5) Research, Education, Outreach and Training (REACHOUT). Table 13 placed below shows the annual budgetary allocation for the PRV programme.

Table 13 Budget requirements: PRV

There has been provisional budgeting for the PRV project, yet the allocation appears to have been left to NCPOR with often wavering by the government, as brought out in para 3 above. Though the Government is in the full knowledge of the requirement of PRV, yet the PRV project has been engulfed in procedural red-tapism and delays which sadly has been witnessed as a regular feature of Indian procurements. The PRV procurement tale is a saga of unfettered delays and invaluable loss of precious foreign exchange as also cost overruns which have impeded the scientific research.

The induction of PRV in India will afford ample opportunity to the ruling political class to build favourable public perception and media hype. The PRV project should have witnessed active cooperation among various Ministries and Departments/organisations like the MEA, MoES, NCPOR, SCI, GSL and so on which appears to be missing in the Indian context. The resultant delay in procurement of the PRV has not only escalated the project cost but portrays stark fissures between the Indian political rhetoric and corresponding deliverables. Government departments are hierarchical organisations. A large body of literature shows that there is a conflict between the individual and the organisational objectives at every stage of the hierarchy (Singh, 2010). Sadly, the most adversely affected by the delayed induction of the PRV i.e. the scientists have also remained muted spectators and since Arctic grabs little traction in the local masses and media, there is little outcry and complains.

10 Asian participation

The relationship between Asia and the Arctic is a complex one and not simply reducible to questions of security and resource politics on the one hand and implicating a small number of Asian states on the other hand. Moreover some Asian cities such as Sapporo, Seoul, Shanghai and Singapore are important providers of expert knowledge on the Arctic and hubs for transnational exchange and collaboration (Dodds et al., 2020). The beginnings of entry in the Arctic for the Asian countries is varied among the Asian countries as South Korea and China had expressed interest in becoming Arctic Council Observers in 2007 while Japan and Singapore submitted their applications in 2009 and 2011 respectively. India was comparatively quite delayed in applying for observer status in Nov 2012. The main reason thereof was a dilemma to join the Arctic system by ceding some diplomatic territory or to remain relevant as an outsider. Pulled between the opposing sides, India chose to toe the line taken by the other Asian states as it lacked the political and economic stature and coherence to be a major player.

It is vital to study the relative progress made by the other Asian countries in their quest for scientific research in the Arctic especially regarding the research vessels as the inclusion of China, Japan, and Singapore as observers coincided with that of India in 2013.

China had purchased its icebreaker R/V(“Snow Dragon”) from Ukraine in 1993 and its second indigenously built icebreaker R/V2 had set off on her maiden voyage for the Antarctic in October 2019. After the purchase of the icebreaker, China has been conducting its scientific research aboard this vessel in the Arctic.

Korea on the other hand is eyeing the immense opportunities opening with the usage of the Northern Sea Route as it is one of the most important shipbuilding nations with the ability to build icebreakers and other special vessels. It has its research vessel ARAON which was made operational in 2010.

Japan has used four icebreakers for its Antarctic research expedition and three of these vessels have already retired. R/Vicebreaker was launched in 2009 is its latest and the active icebreaker currently. Japan also possesses the icebreaking-capable R/V, which is equipped with Doppler radar and other instruments.

Quite like the North-East Asian countries, Singapore also was among the first to build icebreakers. The first Singaporean icebreaker was built in 2008 for Lukoil, which is being employed in the Barents Sea. When seen in contrast to the Indian progress on the possession and development of a PRV, there are stark dissimilarities and differences in the research efforts of the other four Asian countries. Since there is a vast cleft between the professed rhetoric and the action by India, with underlying impetus increasing with the concerns on adverse impacts of climate change as well as greater role India aspires to play at the geostrategic level, it is vital for India to expedite its much delayed PRV project for greater productive research as well as to convey its serious commitment to the Arctic affairs.

The inputs submitted by the Asian observers to the Arctic Council as Observer Review Reports in 2018 for extension/renewal of membership throws the contrasts on the level of involvement and participation as compared to India:

(1) Korea has participated actively in programs and activities of the Arctic Council’s working groups, task forces and expert groups. In the past two years, Korean experts participated in a total of 26 meetings that were organised by the working groups of AMAP, CAFF, PAME, EPPR and SDWG, the task forces of SCTF (Scientific Cooperation Task Force) and TFAMC (Task Force on Arctic Marine Cooperation) and the expert groups of EGBCM (Expert Group on Black Carbon and Methane), PAME SEG (Shipping Experts Group) and EPPR SAR (Search and Rescue). Also, ‘the master plan will also include Korea’s plan to build a second ice-breaking research vessel (Arctic Council, 2018a).

(2) Japan is equipped with various advanced platforms to support scientific observation such as(a research vessel), Ny-Ålesund research station in Svalbard, and the earth observing satellites GCOM-W. It jointly maintains Poker Flat research range super site in Alaska with IARC. It also jointly activate the Ice Base Cape Baranova in Russia, the Spasskaya Pad Forest Station in Yakutsk, and the research sites with Centre for Northern Studies in Canada (Arctic Council, 2018b).

(3) Singapore has continued to attend key AC meetings. We continue to participate actively in various AC working groups, and other events that support the AC’s work as well as the organised fora in Singapore to increase awareness and bring the discussions on the Arctic to South East Asia (Arctic Council, 2018c).

(4) The government of China recognises the great significance of the work of the Council’s working groups, task forces and expert groups in promoting the goals of the Council. China has continuously taken part in the relevant work including but not limited to the following aspects (Arctic Council, 2018d).

(5) Unlike the Asian observers, India has given a brief of its projects being carried out in the Arctic and no specific instances of collaboration/participation with WGs/Expert groups are elucidated. In the 2018 Observer Review Report, India has incorrectly also cited the research cooperation with permanent participants. India commits to have focused research initiatives and looks forward to cooperation from permanent participants to expand the research themes with wider geographic coverage (Arctic Council, 2018e). In this scenario close scientific and logistic collaborations with permanent (sic) will provide much needed momentum for pan-Arctic measurements (Arctic Council, 2018e).

Recently, India has released its draft Arctic Policy and sought public comments thereon till 26 Jan 21 before its finalisation. India’s draft policy reiterates the oft stated goals of scientific research,connectivity, global governance and international cooperation, and human development with emphasis on Indian human resource pool. The inspiration of a delayed Indian policy on the High North appears to be the Chinese White Paper of 2018. The teleconnections between the Arctic climate change to Indian monsoon and influence of a warming Arctic on tropical climate is the key takeaway and basis of this policy. The focus is also on scientific progression and promotion of Indian science fraternity in international events.

Few sore points that have been missed in the draft policy is the Arctic-8’s sensibilities and views on participation by countries lying outside the Arctic Circle as also the evolving scientific collaborations of these states with non-AC member states. Sadly, there is no enunciation of ministerial jurisdiction between MEA, MoES, MoEFCC and quite unlike other observer states there is no nodal agency/ministry earmarked to handle Polar affairs. There is also a lack of policy guidelines on future national goals and interactions with the Arctic region.Listing a wide range of activities – diplomatic, economic, as well as scientific – that New Delhi seeks to pursue in the Arctic, the document reflects what has become a marquee feature of India’s recent global engagements: ambitious planning (Abhijnan, 2021). As is the theme in this paper, India has not concretely identified and stated its position on its investments in Russia’s oil and gas projects or on integration and participation by the indigenous people (PPs).

China has been terming itself as a Near-Arctic State since May 2012 and had released its White Paper on the Arctic in 2018. With the exception of India, countries such as Singapore have appointed Arctic Ambassadors while China and Japan had issued their policy frameworks and strategies long back. In summation, though India’s diplomatic moves in the Arctic have been measured and respectable but lacking the national will to secure a distinctive place in Arctic affairs and policy.

11 Need for scientific collaboration

Considering the wide expanse of the requirement of scientific research there is a need to incorporate novel ways to coordinate, innovate, structure, and invest so as to derive maximum output and fruitful results. The resultant research output is then transferred into the policy domain and shared with partners and associates for the common benefit of mankind. The socio-economic implications of this research have manifold manifestations in the changing global landscape hastened by climate change. Concurrently, there is a political, geopolitical, and diplomatic dimension of research in the Arctic which impacts the foreign relations between nations and affects the regional groupings/forums too. It is vital to actively participate and strengthen international cooperation in the field so that the latest progress is accessible to others to cover the maximum geographical area and outreach.

More arduous than the establishment of a research station at the Arctic is the provision of year-round maintenance and logistical support to ensure quality and efficiency in research. India had taken a leaf from several, mostly advanced countries in establishing “Himadri” which requires huge sums of money for regular and routine upkeep and maintenance. However, considering the strategic and scientific potential of such a research base India chose to ignore the huge gap between India’s economic and financial clout and resources in comparison to the other Observers. Since India professes to possess strong bilateral and friendly ties to many Nordic (Norway/Iceland), Russia and Japan, it would have been prudent to combine the logistical networks with a view to save on huge costs as well as an enhanced focus on making specific centers (hubs) as centres of excellence. Since the facilities in the Arctic are extremely costly, India should channelize its meagre resources in obtaining a PRV earnestly.

Dedicated research vessels capable to operate all year round under any weather conditions in the Central Arctic Ocean and in the Southern Ocean are vital marine infrastructures for polar research (European Science Foundation, 2010). The developed and economically rich nations of Europe are pooling their research vessel resources under the aegis of organisations like COMNAP (Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs) in the Antarctic and FARO (Forum of Arctic Research Operators) in the Arctic and yet India has been adamantly and wastefully splurging money on hiring chartered vessels making little scientific progress. India should emulate the European model and engage in collaborative and synergised research with the other Asian Observers for incisive and fruitful research. India should also address the issue of duration of PRV between the Arctic and the Antarctic and the interoperability of the on-board equipment. The savings on recurring annual icebreaker hiring charges could be better utilised to obtain automated under-ice vehicles, remotely operated vehicles, observatories, moored systems, or ice-tethered buoys. These pieces of equipment can provide data for modelling and long term trend analysis. Another deficiency noticed in the Indian approach to the undertaking of polar research is evidenced that there are no plans or policies to integrate the ship faring operational experience with Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) as also the integration of space capabilities. India has made considerable progress in space technology and it will serve a great purpose to share this information with the Arctic states towards achieving scientific goals.

12 Conclusion

India has been spending considerable amounts of money in polar scientific pursuits but they appear to be generic and repetitive in nature, which in turn is jeopardising the mantle of research diplomacy to further the national interests. The execution of government projects in India has been marred by very high cost and time overruns. Though the capital expenditure on the PRV is marginal yet the progress on this project provides a dim view of India’s lax attitude to the geostrategic calculations. Considering the lofty promises made by India by asserting its stakes in the research at the polar regions, the delay in procurement and operationalization of the PRV by over ten years has led to a two-thirds fold increase in the cost outlay. Unlike the pre-liberalisation era in India, where there were financial constraints in the implementation of projects, the present delay in the acquisition of PRV stems from India dragging its feet in fulfilling its geopolitical ambitions. There seems to be a mismatch between the Indian national polar policies and management measures on Arctic Science. One of the key reasons for the deficit in Indian position is the unfortunate gap which has been persisting between the various Ministries and organisations, imperilling the national Polar programme.

From the foregoing, it is evident that over the last several years, India has been paying substantial sums of money to foreign-owned and operated PRVs. The availability and timeframe of operation of these vessels also has to be aligned with the availability of ships with the chosen partner vessel companies and India does not have the flexibility and direction to venture at chosen time and locations. Instead of incorporating hugely successful shipbuilding nations like Korea, China, or Nordic countries to progress its bilateral strategic engagement, India is planning to progress the design and fabrication of PRV in India, despite a lack of experience and expertise. It is imperative for the policy advocates to assume control of this situation, earnestly.

The Arctic offers invaluable lessons in cooperation in Polar research with many examples like the 1995 German-Russian expedition to the Laptev Sea, 2019 MOSAiC expedition with the participation of 20 countries aboard the German vesseland many others. The scientific cooperation between the Asian Arctic observers’ states also remains woefully inadequate due to the prevailing mutual mistrust in sharing data and resources. India has also not explored this avenue to partner with Asian observers due to strategic rivalry and competition, especially with China. Since there already is a precedent in the form of International Arctic Science Committee (IASC) formed in 1990 to foster scientific cooperation in the Arctic as both an object and place of scientific research and international cooperation, a new forum for enhancing scientific cooperation among observer states may be introduced for mutual benefit.

The lack of PRV is affecting the quality of scientific research as well as reach to explore new territories and Indian research thus remains inadequate and uninspiring. The increasing economic, political, and geostrategic significance of the Arctic, which has witnessed tremendous transformation in recent times calls for more robust and tangible assertions by stakeholders including India to fulfil its aspirations.

For India to project an influential and active position in the Arctic scientific research, it is essential to have an all year round unbridled access to the region. To maintain some credibility in its research, there is a requirement to cover the deep Arctic and ice-covered waters of Antarctic. The polar icebreaker research vessel is an essential requirement in the national policy in a rapidly changing Arctic region, which is evincing interest of a plethora of non-Arctic states and the consequent interplay of geopolitics and geo-economics. There seems to be a huge divide between India’s stated position of ‘We are extremely interested in the Arctic region and intend to play an active role in the Arctic Council too(IANS, 2013) and her actions in various fields which fall short of the promise, projecting India in a poor light. These actions and India’s seriousness in Arctic scientific research are being keenly viewed especially by the Arctic states and there seems to be a big divide between the rhetoric and actions. The solution requires a holistic charting of the national objectives with streamlining of several parameters and scientific engagement should be the undisputable start point towards India’s professed goals in the Arctic region.

Acknowledgements The author thanks three anonymous reviewers, and Associate Editor, Dr. Jian Yang for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Abhijnan R. 2021. India releases draft Arctic Policy, The Diplomat, 05 January 2021. [2021-02-28]. https://thediplomat.com/2021/01/india- releases-draft-arctic-policy/.

Alfred-Wegener-Institut (AWI). 2008. The Kongsfjorden System – a flagship programme for Ny-Ålesund. [2020-03-22]. https://epic.awi. de/id/eprint/32450/1/ConcludingDocument_KongsfjordenSystem.pdf.

Arctic Council. 2016. India’s engagement with Arctic Council. [2020-01- 12]. https://oaarchive.Arctic-council.org/bitstream/handle/11374/1869/EDOCS-4033-v1-2016-12-16_India_Observer_activity_report.PDF?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Arctic Council. 2018a. The Republic of Korea’s 2018 Observer Review Report. [2019-11-12]. https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/ 11374/2262.

Arctic Council. 2018b. Japan’s 2018 Observer Review Report. [2019-11-12]. https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/2259.

Arctic Council. 2018c. The Republic of Singapore’s 2018 Observer Review Report. [2019-11-12]. https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/ handle/11374/2263.

Arctic Council. 2018d. The People’s Republic of China’s 2018 Observer Review Report. [2019-11-12]. https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/ handle/11374/2251.

Arctic Council. 2018e. The Republic of India’s 2018 Observer Review Report. [2019-11-12]. https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/1137 42256.

Bischof K, Convey P, Duarte P, et al. 2019. Kongsfjorden as harbinger of the future Arctic: knowns, unknowns and research priorities. Chapter 14: The Ecosystem of Kongsfjorden, Svalbard//Hop H, Wiencke C (eds). The Ecosystem of Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Advances in Polar Ecology, vol 2. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 537-562, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46425-1_14.

Brady A M. 2013. Diplomatic chill: politics trumps science in Antarctic Treaty System. World Politics Review. (2013-03-19) [2020-01-03]. https://asoc.nonprofitsoapbox.com/storage/documents/news/March_2013/WPR_Article___Diplomatic_Chill__Politics_Trumps_Science_in_Antarctic_Treaty_System.pdf.

Colombo Dockyard PLC. 2014. Coldock Times. [2019-12-12]. https://uqp.no/Userfiles/Upload/files/2014-10-01%20Coldock%20Times%20Vol%208%20E%20Mail%20%20-%20Version%20FINAL%20LTE.pdf.

Directorate General of Shipping. 2018. Guidelines for advanced training course for ships operating in polar waters. [2020-01-02]. https:// www.dgshipping.gov.in/writereaddata/ShippingNotices/201809170557076658977dgs_cir22_2018_trg.pdf.

Dodds K, Yuan Woon C. 2020.Introduction: the Arctic Council, Asian states and the global Arctic. ‘Observing’ the Arctic. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 1-27, doi:10.4337/9781839108211.00006.

European Science Foundation (EPB). 2010. EPB strategic position paper: European research in the polar regions: relevance, strategic context and setting future directions in the European research area. [2019-09-26]. https://trimis.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/project/ documents/20121005_163319_85545_European_Research_PolarRegions.pdf.

Goa Shipyard Limited, 2019. Notice inviting expression of interest. [2020-01-02]. https://goashipyard.in/file/2019/04/EOI-29042019.pdf.

IANS, 2013. India to play active role in Arctic Council, Hindustan Times. [2019-11-22]. https://www.hindustantimes.com/delhi/india-to-play- active-role-in-Arctic-council/story-MRPA85wG4NsTAtV3okXFUL. html.

Koenig R. 2019. Polar bears, ice cracks and isolation: Scientists drift across the Arctic Ocean, NPR, 13 Dec). [2019-12-04]. https:// www.npr.org/2019/12/04/784691513/polar-bears-ice-cracks-and-isolation-scientists-drift-across-the-Arctic-ocean?utm_campaign=storyshare&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_medium=social.

Ministry of Earth Sciences. 2012. Notification. (2012-09-19) [2019-09-12]. https://moes.gov.in/writereaddata/files/rr.pdf.

Ministry of Earth Sciences. 2015a. Procurement of polar research vessel. [2020-03-23].https://moes.gov.in/content/procurement-polar-research-vessel.

Ministry of Earth Sciences. 2015b. Procurement of polar research vessel. [2020-02-25]. https://moes.gov.in/writereaddata/files/RS_US_05_234 2015.pdf.

Ministry of Earth Sciences. 2015c. Replacement of Maitri Station. [2019-10-02]. https://moes.gov.in/programmes/replacement-maitri- station.

Ministry of Earth Sciences. 2018a. Construction of polar research vessel. [2020-01-12]. https://moes.gov.in/programmes/construction-polar- research-vessel.

Ministry of Earth Sciences. 2018b. Earth Science projects. [2019-11-26]. https://www.moes.gov.in/writereaddata/files/LS_EN_2037_07032018.pdf.

Ministry of External Affairs. 2013. India and the Arctic. [2019-12-21]. http://www.mea.gov.in/in-focus-article.htm?21812/India+and+the+Arctic.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2012. Annual Report 2011-12. [2019-12-12]. http://www.ncaor.gov.in/annualreports.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2013. Annual Report 2012-13. [2019-12-12]. http://www.ncaor.gov.in/annualreports.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2014. Annual Report 2013-14. [2019-12-12]. http://www.ncaor.gov.in/annualreports.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2015a. IndARC multi-sensor mooring. [2019-12-23]. http://www.ncaor.gov.in/pages/ display/398-indarc.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2015b. Annual Awards-2015, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Dr. Shailendra Saini. [2019-09-12]. https://moes.gov.in/writereaddata/files/shailendra_saini. pdf.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2015c. Annual Report 2014-15. [2019-12-12]. http://www.ncaor.gov.in/annualreports.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2016. Annual Report 2015-16. [2019-12-12]. http://www.ncaor.gov.in/annualreports.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2017. Annual Report 2016-17. [2019-12-12]. http://www.ncaor.gov.in/annualreports.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2018. Annual Report 2017-18. [2019-12-12]. http://www.ncaor.gov.in/annualreports.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2019a. Annual Report 2018-19. [2019-12-22]. http://www.ncaor.gov.in/annualreports.

National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). 2019b. Mirza Javed Beg, Scientist ‘G’ and Project Director (Logistics) has been elected as Vice Chair of Council of Managers of National Antarctic Program (COMNAP). [2019-10-12]. http://ncaor.gov.in/news/view/ 307.

National Institute of Ocean Technology. 2011. Recruitment rules for autonomous institutes under MOES (scientists). [2019-10-03]. https://www.niot.res.in/Recruitment%20Rules/Scientist.pdf.

Nayak S. 2019. Cooperation with China to advance scientific and technological knowledge. China Rep, 55(2): 145-153, doi:10.1177/ 0009445519834700.

Sabha R. 2018. Three hundred fifteenth report. Demands for Grants (2018-19) of the Ministry of Earth Sciences (Demand No. 25).( 2018-03-13) [2019-11-03]. https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/ Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/19/103/315_2019_1_14.pdf.

Scully T. 2011. The development of the Antarctic Treaty System//Berkman P A, et al. Science diplomacy: Antarctica, and the governance of international spaces. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 29-38. doi:10.5479/si.9781935623069.29.

Stensdal I. 2013. Asian Arctic research 2005-2012: harder, better, faster, stronger, Fridtjof Nansen Institute. FNI Report 3/2013. Lysaker, FNI, 2013, 39 p. [2019-10-22]. https://www.fni.no/publications/asian- arctic-research-2005-2012-harder-better-faster-stronger.

Singh R. 2010. Delays and cost overruns in infrastructure projects: extent, causes and remedies. Economic and Political Weekly, 45(21): 43-54.

Tejonmayam U. 2015. India to procure ship that can break through 1.5m thick ice. Economic Times. (Last updated, 2015-03-24) [2019-12-09]. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/science/india-to-procure-ship-that-can-break-through-1-5-m-thick-ice/articleshow/46672554.cms?from=mdr.

The Shipping Corporation of India Limited. 2019. [2019-10-12]. https:// shipindia.com/pdf/performance/69thAnnualReport2018-20191.pdf.

Appendix Table

Appendix Table S1 Email interviews with Working Groups/Permanent Participants of the Arctic Council

No.Working Groups/Permanent ParticipantsInterviewer or E-mailDate (YYYY-MM-DD)Contents of interview 1PAME (Protection of Arctic Marine Environment)amap@amap.no2020-01-15This is to inform you that for the 5 last years there have been no contribution nor participation from India to AMAP in regards to item listed under a) to d) included. As for your request under item e) you will find a direct link on AMAP website (https://www.amap.no/about/organisational-structure) that will direct you to the list of all Arctic Council observers, including India on the following item: “the Arctic Council Observing Countries and Organizations.” Observers to the Arctic Council are automatically also observers to its working group, including AMAP.India has participated in one PAME Meeting (held on 04-07 February 2019 at Malmo, Sweden) since it became an Arctic Council Observer. This was the first time a representative from India participated in a PAME working group meeting. And no presentation was given by the Indian representative. The representative from observer countries included China, the UK, Italy, Japan, Germany, Poland, Netherlands, ROK, and India. It also participated in a workshop ‘Systematically Engaging with Observers on PAME’s Shipping-Related Work’, held on 04 Jun 2019 at London. 2Gwich’in CouncilMahsi Devlin, GCIadmin@gwichin.nt.ca2019-12-18I don’t believe there have been any specific contributions to GCI, but you could look at contributions to the Arctic Council. 3NAMMCO (North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission)Charlotte Winsnes, nammco-sec@nammco.org2019-12-17India is not an observer country to NAMMCO and has never participated nor contributed in any way to the work of NAMMCO. 4EPPR (Emergency Preparedness, Prevention and Response)Jens Peter Holst-Andersen, JPH@fmn.dk2019-12-17India has not been an active part of the work in EPPR the last 5 years and has therefore not submitted any proposals. 5Saami CouncilAile Javo, saamicouncil@saamicouncil.net2019-12-20The answer to all of your questions is zero. 6ACAP (Arctic Contaminants Action Program)Kseniia Iartceva, Kseniia@arctic-council.org2020-01-02Thank you for your message. With reference to your inquiry, India has not been actively involved in the work of the ACAP Working Group during the last 5 years.In November 2018, a representative of the Indian National Center for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR) attended the ACAP Working Group meeting in Reykjavik, Iceland. However, this is the only example of India’s participation in ACAP’s activities.There is one contribution by India I am aware of, but it is not connected to ACAP’s work, though it is related to the problem of short-lived climate pollutants. India provided data for the Summary report by the Arctic Council’s Expert Group on Black Carbon and Methane (2017). I have attached the report hereto for your information. 7OSPAR Commission (The Oslo and Paris Commissions)secretariat@ospar.org2020-01-06India is not a Contracting Party to the OSPAR Commission.You may need to contact Arctic Council for answers to your questions 8AMAP (Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme)amap@amap.no2020-01-15This is to inform you that for the 5 last years there have been no contribution nor participation from India to AMAP in regards to item listed under (a) to (d) included. As for your request under item (e) you will find a direct link on AMAP website (https://www.amap.no/about/organisational-structure) that will direct you to the list of all Arctic Council observers, including India on the following item: “the Arctic Council Observing Countries and Organizations”. Observers to the Arctic Council are automatically also observers to its working group, including AMAP. 9CAFF (Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna)coutney@caff.is2020-01-16Answers a-d were unanswered because there have been none to date. My answer to e can be found in my last email. India is an active and interested partner in developing cooperation through CAFF's AMBI. I trust I have answered this request.Recently CAFF has had good cooperation and discussions with India about deepening our partnership through CAFF’s Arctic Migratory Birds Initiative (AMBI). In December 2018 a representative of the Bombay Natural History Society attended our AMBI technical workshop in Hainan, China to help finalize our AMBI Work Plan 2019-2023. In November 2019 the AMBI Chair and AMBI Global Coordinator attended the CWAMWAF conference in Lonavala at the invitation of the Bombay Natural History Society. AMBI staff gave two plenary addresses, participated in panels, and hosted a special session to further present and discuss AMBI implementation actions of relevant to the Central Asian Flyway. In addition, AMBI staff were invited to Delhi to meet with relevant Ministerial staff to discuss further partnerships and AMBI implementation. There was keen interest to partner further. Further events and discussions are planned for February 2019 at the CMS COP13 in Gandhinagar, India. 10Aleut International Associationliza.mack@aleut-international2020-01-17I am not aware of any contributions from India to Aleut International Association or our research efforts.

6 September 2020;

8 March 2021;

19 March 2021

, ORCID: 0000-0001-7201-1647, E-mail: nikhilginni@gmail.com

10.13679/j.advps.2020.0027

: Pareek N. Assessment on India’s involvement and capacity-building in Arctic Science. Adv Polar Sci, 2021, 32(1): 50-66,

10.13679/j.advps.2020.0027

杂志排行

Advances in Polar Science的其它文章

- Information for authors

- Editorial Note

- Complete genome analysis of bacteriochlorophyll a-containing Roseicitreum antarcticum ZS2-28T reveals its adaptation to Antarctic intertidal environment

- Leveraging the UAV to support Chinese Antarctic expeditions: a new perspective

- Seabird and marine mammal at-sea distribution in the western Bering Sea and along the eastern Kamtchatka Peninsula

- Biomarker records of D5-6 columns in the eastern Antarctic Peninsula waters: responses of planktonic communities and bio-pump structures to sea ice global warming in the past centenary