Surgical treatment of gallbladder cancer: An eight-year experience in a single center

2021-01-13YasuyukiKamadaTomohideHoriHidekazuYamamotoHidekiHaradaMichihiroYamamotoMasahiroYamadaTakefumiYazawaMasakiTaniAsahiSatoRyotaroTaniRyuheiAoyamaYudaiSasakiMasazumiZaima

Yasuyuki Kamada, Tomohide Hori, Hidekazu Yamamoto, Hideki Harada, Michihiro Yamamoto, Masahiro Yamada, Takefumi Yazawa, Masaki Tani, Asahi Sato, Ryotaro Tani, Ryuhei Aoyama, Yudai Sasaki, Masazumi Zaima

Yasuyuki Kamada, Tomohide Hori, Hidekazu Yamamoto, Hideki Harada, Michihiro Yamamoto, Masahiro Yamada, Takefumi Yazawa, Masaki Tani, Asahi Sato, Ryotaro Tani, Ryuhei Aoyama, Yudai Sasaki, Masazumi Zaima, Department of Surgery, Shiga General Hospital, Moriyama 524-8524, Shiga, Japan

Abstract

Key Words: Gallbladder cancer; Surgery; Prognosis; Outcome; Metastasis; Lymph node; Extrahepatic bile duct

INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) remains a relatively rare malignancy with a variable presentation[1-7], but it is the most common biliary malignancy and has the worst prognosis[3,4,7].Although GBC generally carries a poor prognosis[1-4,7-15], complete surgical resection is associated with improved outcomes in GBC patients[1,2,11,14,16-23].Some surgeons have suggested that aggressive surgeries [e.g., resection of the extrahepatic bile duct (EHBD), extended hepatectomy and intentional lymph node dissection (lymphadenectomy) of the para-aortic lymph nodes (LNs)] may improve long-term survival in patients with advanced GBC[1,2,9,11,13,14,16,18-25].Metastatic LNs, invasion into the peribiliary nerve plexuses and positive surgical margins of the biliary tract are important prognostic factors[1,7,11,15,18,21].

Although radical resection is considered by many to be the ideal management strategy for GBC[1,2,11,14,16-23], selecting the appropriate surgical procedure based on the depth of the primary tumor and the clinical stage of GBC is still controversial[1-4,10,11,14,16,17,19,20,23,24,26].Optimal treatment for advanced GBC is unclear[1,2,24], especially in patients with T2 disease according to the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification[27].The use of radical cholecystectomy and extended procedures with EHBD resection are a matter of debate[1,2,10,14,16,20,24,25].Radical cholecystectomy involves an extended cholecystectomy with a full-thickness resection and a wedge resection with partial hepatectomy of the gallbladder bed[28-31].The impact of routine resection of the EHBD, extended LN dissection, and major hepatectomy on outcomes still lacks consensus[1,11,16,20,24].

We retrospectively investigated our patients who underwent surgical treatment for incidentally or non-incidentally diagnosed GBC; their data are presented together with a discussion of the therapeutic strategies for GBC and a literature review.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A total of nineteen GBC patients who underwent surgical treatment at our institution from January 2011 to March 2019 were enrolled in this study.The patients comprised five men and fourteen women, with a mean age of 72.5 ± 11.5 years.Two patients had a past history of other cancers, and one patient had cholelithiasis as a comorbidity.None had viral hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.The GBCs were staged according to the TNM classification[27].

This retrospective study was approved by the ethics review committee for clinical studies of our institution.This study was performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.Informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment.

Statistical analysis

All results are shown as mean ± SD or median (range).Survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the log-rank test was used for between-group comparisons.All calculations were performed using SPSS Software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).Values ofP< 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Preoperative management

Preoperative profiles are summarized in Table 1.Six patients presented with fever and abdominal pain, and two patients had obstructive jaundice; the remaining eleven patients (57.9%) were asymptomatic (Table 1).The eight symptomatic patients were categorized as stage ≥ IIB (Table 1).Biliary drainage was required in two symptomatic patients with stage IVB disease (Cases 14 and 17) due to obstructive jaundice and acute cholangitis (Table 1).

Preoperative evaluation

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction was observed in two patients (Cases 2 and 16; Table 1).No patients had occupational risk factors for GBC.Six patients were initially diagnosed with benign diseases (two stage IIB patients and one each with stage IA, IB, IIA and IIIA disease) (Table 1), and these patients were classified as having suspicious or incidental GBCs.The preoperative stages of patients who received radical surgery were stage IVB (five patients); stage IIA (three patients); and stages IIB, IIIA, IIIB and IVA (two of each stage; Table 1).

Preoperative chemotherapy and radiation

None of the patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation.One patient received chemotherapy [four courses with gemcitabine (GEM) + cisplatin (CDDP)] and radiation (60 Gy) for unresectable GBC; this patient underwent conversion surgery (Case 10).

Surgical treatment

Operative factors are summarized in Table 2.Eleven patients underwent primary extended cholecystectomy with full-thickness resection and partial hepatectomy of the gallbladder bed, and three patients underwent wedge resection of the gallbladder bed as a two-stage surgery (Table 2).Although partial hepatectomy and/or wedge resection of the gallbladder bed were performed in fourteen patients, only one patient received a systemic hepatectomy (right-lobe hepatectomy accompanied by partial caudate lobectomy; Case 17).

A total of eight patients (three with stage IIB disease and one each with stage IIA, IIB, IIIA, IVA and IVB disease) underwent intentional resections of the EHBD, including five who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (Table 2).Lymphadenectomy of the para-biliary, para-arterial and peri-portal venous LNs was performed in eleven patients (57.9%; three with stage IIIB disease; two each with stage IIB, IIIA, IIIB and IVB disease; and one each with stage IIA and IVA disease).The para-aortic LNs were dissected in one stage IVB patient (Case 19).

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was initially performed in seven patients with a preoperative diagnosis of benign disease, and three of these patients (two with stage IIB disease and one with stage IIIA disease) received two-stage surgery based on pathological findings.All three underwent wedge resection, and one patient received resection of the EHBD (Cases 6, 7 and 8; Table 2).Three patients (stages IA, IB and IIA) did not receive two-stage surgery (Cases 1, 2 and 4).

Table 1 Preoperative evaluation, chemotherapy and/or radiation, and the final stage

Curative resections, evaluated as graphic and surgical R0 according to the Japanese guidelines (General rules for clinical and pathological studies on cancer of the biliary tract[32]), were accomplished in fifteen patients.A total of four patients (three with stage IIIA and one with stage IVA disease; Cases 9, 10, 11 and 17) received noncurative resections; the biliary cut surface or surgical surface margins were each positive in two patients (Table 3).

Table 2 Operative factors

Intraoperative factors

The median operative time was 269 min (range, 32-775 min).Median blood loss was 430 mL (range, 0-3700 mL), and blood transfusions were needed in four patients.Intraoperative histopathological examination was performed in eight patients to assess the primary tumors, cut surface of the biliary tract, nerve plexus and LNs.Although carcinomas were correctly identified in all cases, the extension (i.e., oncological depth) of the primary tumor was misdiagnosed by intra-operative examination in one patient (Case 6).

Postoperative course during the early postoperative period

Postoperative complications were observed in six patients (four cases of intraperitoneal abscess and one each of pancreatitis and pancreatic fistula), and these complications were categorized as grade 2 (n= 3), grade 3a (n= 2) and grade 3b (n= 1) according to the Clavien–Dindo classification[33](Table 2).

Pathological assessment

The pathological findings are summarized in Table 3.Diagnoses of tubular, papillary, and poorly-differentiated adenocarcinomas were made in 12, 3 and 2 cases, respectively.Additionally, one adenosquamous cell carcinoma and one neuroendocrine carcinoma were diagnosed.No satellite lesions of dysplasia and/or neoplasia were observed.Only one patient (Case 1) was diagnosed with mucosal cancer (a so-called “m cancer”), and neither a second-stage surgery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy nor an extended cholecystectomy was chosen for this patient (Table 2).

The primary tumor was located in the liver in 10 patients and the ventral side in nine (Table 3).Invasions into the lymphoid duct, vessels and peribiliary nerve plexus were pathologically assessed, respectively.These invasions occurred in six, ten and five cases, respectively (Table 3).Notably, nine GBCs invaded into the GB neck or cystic duct (Table 3).

Positive margins at the biliary cut surface were observed in two patients (Cases 11 and 17), and positive margins at the ventral, dorsal and/or hepatic surfaces were identified in two patients (Cases 10 and 12; Table 3).

Table 3 Pathological findings

The final TNM stage based on pathology[27]was stage IA, IB or IVA in one patient each; stage IIB or IVB in two patients each; stage IIA in three patients; stage IIIB in four patients and stage IIIA in five patients (Table 1).

Lymphoid metastasis

The median number of harvested LNs was 13 (range, 1–35).Actual LN metastases were observed on pathology in five patients, with a median of two metastatic LNs per patient (range, 1–18) (Table 3).In one patient, six of the seven para-aortic LNs were metastatic (Case 19).

Histopathological assessment of the LNs around the cystic duct (i.e., the 12c LNs according to the Japanese guideline[32]) was performed in four patients with suspicious or incidental GBC, and metastasis was detected in two patients.These two cases had other LN metastases (Cases 15 and 16; Table 3).

Nerve plexus metastasis

Invasion of the nerve plexus was pathologically observed in five patients, and three of these cases (60.0%) were GBCs with invasion into the GB neck and/or cystic duct (Table 3).Although these five patients also underwent resection of the EHBD (Tables 2 and 3), all five patients died from metastases and/or recurrences (Table 4).In two patients with advanced GBC, positive margins were observed at the cut surface of the biliary tract in spite of EHBD resection (Cases 11 and 17; Table 3).Only one of eight patients who received EHBD resection (12.5%) survived without any metastases and/or recurrences (Case 3; Tables 2 and 4), and this patient was categorized as stage IIA (Table 1).

Liver metastasis

A total of fifteen patients received hepatectomies (Table 2).Pathological examination of the resected liver specimens revealed direct invasion into the liver in seven patients (Table 3).Liver metastases occurred postoperatively in six patients (three in segment 4, one each in segments 5 and 7, and one in the majority of the liver); four of the targeted segments were located in the left side of the liver (66.7%) (Table 4).Four of these six patients’ primary tumors showed vessel invasion (Table 3).Four metastatic tumors occurred in the left lobe (Table 4), and no metastases were observed in the caudate lobe.

Adjuvant and postoperative chemotherapy

Only one patient (stage IIIA) received adjuvant chemotherapy: Six courses of S-1 (Case 11).Three patients received chemotherapy after detection of metastases and/or recurrences.The regimens employed were GEM + CDDP, GEM + CDDP followed by GEM + S1, and CDDP + vinblastine, respectively (Cases 7, 10 and 19).

Outcomes

The clinical courses of all patients were followed for a median of 2.03 years (0.15–5.05 years).Metastasis and/or recurrence was observed in fourteen patients (74.7%); the five patients without metastasis/recurrence had stage IIA disease (two patients) and stage IA, IB or IIB disease (one of each) (Tables 1 and 4).Metastasis occurred in the liver (six patients), para-aortic LNs (four patients) intraperitoneal dissemination (four patients), and local recurrence (four patients) (Table 4).

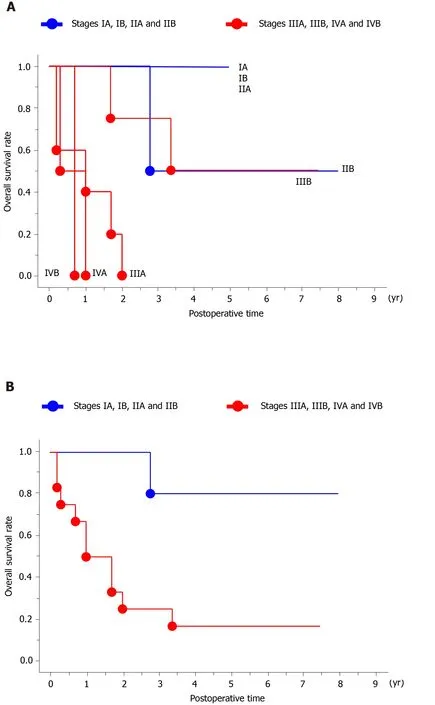

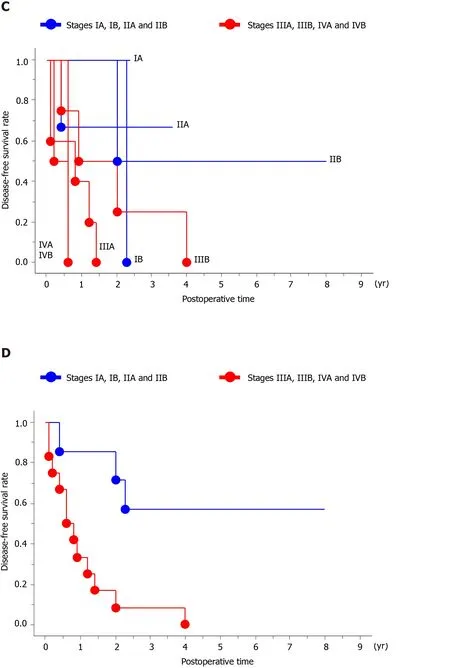

The overall survival curves by stage are shown in Figure 1A; there was a significant difference in overall survival between patients with stage ≤ IIB and stage ≥ IIIA disease (P= 0.0080; Figure 1B).The overall median survival in the eleven patients with oncological death was 1.66 years (range, 0.16-3.36 years; Figure 2A).

The disease-free survival curves by stage are shown in Figure 1C; there was a significant difference in disease-free survival between patients with stage ≤ IIB and ≥ IIIA disease (P= 0.0054; Figure 1D).The disease-free interval of the fourteen patients with recurrences was 0.79 years (0.12–4.01 years; Figure 2B).

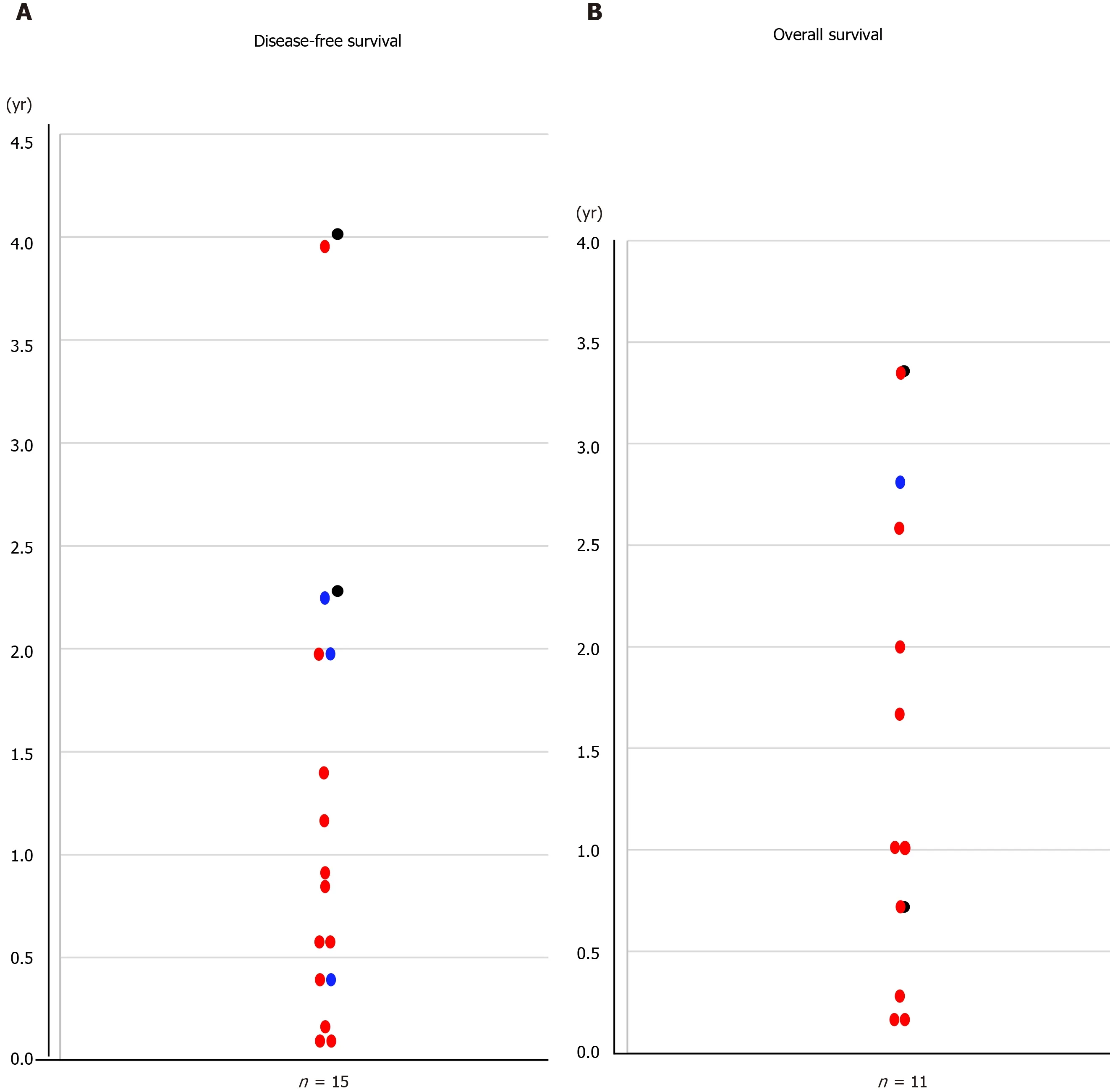

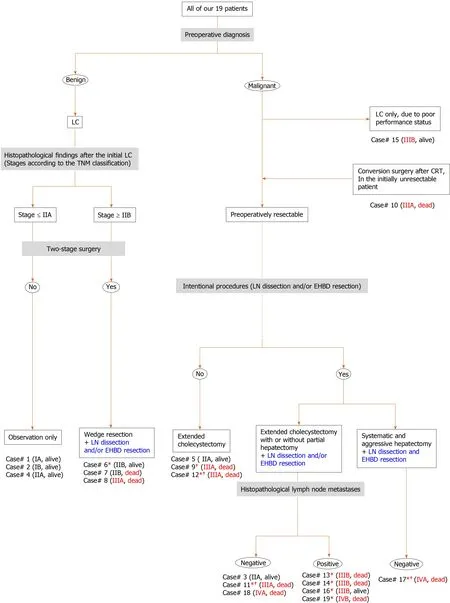

Comprehensive flowchart for important points in our patients

The specific characteristics of each patient may be difficult to understand.Characteristic findings and important points (e.g., preoperative diagnosis, surgical treatment, histopathological assessments, stage according to the TNM classification and prognosis) are summarized in Figure 3.

Table 4 Metastases, recurrences and outcome

DISCUSSION

In GBC patients, the presence of associated symptoms is considered a relative contraindication to radical resection as these patients have a poor prognosis and high postoperative morbidity[1-3,9].Of our eight symptomatic patients (Table 1), all were categorized as stage ≥ IIB, and seven (87.5%) showed poor outcomes (Table 4).Although jaundiced patients with advanced GBC should be considered as candidates for surgical resection, careful evaluation is important before undertaking aggressive surgery in this population[2,9].

Certain factors (e.g., liver injury and occupational history) are associated with an increased risk of developing GBC[12].In particular, data support a relationship between pancreaticobiliary maljunction and GBC[34].Among our patient population, only two cases (10.5%) had pancreaticobiliary maljunction.

Gallbladder cancer can be suspected preoperatively, identified intraoperatively, or discovered incidentally on final pathology[2-4,26,35].In cases with suspicious or incidental GBCs, lesions tend to be stage T2 or T3 by the TNM classification[26,27].Once GBC is diagnosed, a two-stage surgery should be considered[26], although simple or extended cholecystectomy produces comparable survival outcomes in GBC patients with T1 lesions[17].Among our patients, the three with suspicious/incidental GBC of lower stages showed excellent outcomes without two-stage surgery (Cases 1, 2 and 4).Perforation during the initial surgery carries a higher risk of dissemination[35], although extended resection of adjacent organs may not be necessary in order to achieve radicality even in this instance[25].Therefore, radical cholecystectomy (e.g., fullthickness resection and extended cholecystectomy) should be considered in the absence of unexpected rupture among patients with suspicious and incidental GBCs.In this study, we assessed the importance of metastasis to the 12c LNs[32]in suspicious and incidental GBCs.Of the four patients with suspicious/incidental GBCs in which the 12c LNs were histologically assessed, the two patients with 12c LN metastasis (Cases 15 and 16) had other metastatic LNs, while the two patients without 12c LN metastasis did not have other LN metastases (Cases 2 and 7).Even though the number of sampled LNs was small (1 or 2), the 12c LNs seem to be useful sentinel nodes in patients with suspicious and incidental GBCs.For patients with suspicious/incidental GBCs, full-thickness cholecystectomy and sampling of the 12c LNs may be suitable for the initial surgery, although two-stage surgery may be required based on histological findings.

Figure 1 Overall and disease-free survival.

Figure 2 The median overall and disease-free survival.

GBCs tend to invade adjacent structures, including the liver parenchyma, bile duct, major vessels, nerve plexuses and regional LNs[1,11,14,20].Metastatic LNs and bile duct margins are important prognostic factors[1,7,11,15,18-21], and invasion into the nerve plexuses is also a significant independent prognostic factor[11].Intentional dissection of the LNs and nerve plexuses is still controversial[1,2,11,15,16,19,20,22,24,25].Extended dissection of LNs and/or nerve plexuses should involveen blocresection of the EHBD[1,11,16,20,24,36].From the viewpoint of achieving curative resection, EHBD resection may have some advantages[1,11,16,20].However, although routine EHBD resection in GBCs without bile duct invasion is associated with improvements in harvested LNs and local recurrence rate, this procedure does not improve the survival rate and is associated with a higher morbidity rate[14,16,24].Among our patients, four of the five patients with metastatic LNs received intentional extended LN dissection, but all these patients developed metastases and/or recurrences (Cases 13, 14, 16 and 19).Extended LN dissection worked well in only one patient with early stage disease (Case 3).Moreover, nerve plexus invasion was observed in five patients, and all five of these patients succumbed to oncological death despite EHBD resection (Cases 11, 13, 14, 17 and 19).Of patients undergoing EHBD resection, only one patient with early stage disease survived without any metastases and/or recurrences (Case 3).Unfortunately, extended dissection of the nerve plexuses was not beneficial for advanced GBC patients with invasion into the GB neck and/or cystic duct in our study.Similar to previous reports[1,9,11,15,19,20,24], our advanced GBC patients with metastatic LNs and invasion into the nerve plexus experienced poor outcomes even after aggressive surgery including removal of the EHBD.

Figure 3 Comprehensive flowchart of important points in our patients.

Major hepatectomy for biliary hilar malignancy may involve intraoperative risks and/or postoperative mortality[14,37].Extended resection with partial hepatectomy and dissection of the regional LNs may be an option for GBC patients with T2 lesions[1,2,21], but major hepatectomy should only be performed in select cases[1,10].Minimal hepatectomy should be performed to achieve curative resection whenever possible[1].Drainage from the gallbladder is an important metastatic pathway[6,36], especially for liver metastases[6,36].Previous publications have suggested that biliary drainage into the left-sided liver, including the caudate lobe, has an impact on metastasis[6,21,23,36,38,39].Some physicians have documented that the caudate lobe is an important target site for metastases[21,23,26,38,39]and recommend complete resection of the caudate lobe, including Spiegel’s lobe[21,36,38,39].Among our patient population, liver resections were performed in fifteen patients, but a systematic hepatectomy was only performed in one patient (Case 17).Despite hepatic resection, the liver was preserved as a target site of metastases in our patients.We observed metastases in the left-sided liver (Cases 12, 17, 18 and 19) but did not detect metastases in the caudate lobe in any of the eighteen patients with caudate lobe remnants.Accordingly, we suggest that complete resection of the caudate lobe may not be necessary in all cases.Positive surgical bile duct margins should be considered a strong negative prognostic factor[1], and our two patients with positive biliary tract margins showed very poor outcomes (Cases 11 and 17).Therefore, although minimal hepatectomy should be considered for some GBC patients if complete resection can be accomplished by this method[1,10], aggressive hepatectomy is mandatory if needed to accomplish negative biliary margins[1,20].

Overall survival and disease-free survival are shown in Figure 1, both of which clearly differ for patients with stage ≤ IIBvsstage ≥ IIIA disease.The median overall and disease-free survival times for patients were 1.66 and 0.79 years, respectively.Aggressive treatment, including extended surgeries, may be beneficial for early-stage GBC[1,25], especially in populations with disease stages ≤ IIB.However, the poor prognosis of advanced GBC has been documented even after extended and/or aggressive procedures[1,9,15,20,24].Despite this poor prognosis, the role of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for GBCs remains controversial[4].Among our patients, only one patient (who became resectable) received chemotherapy and radiation before conversion surgery (Case 10), and adjuvant chemotherapy was only performed in one patient with a non-curative resection (Case 11).Some chemotherapy regimens have been developed for GBC[1,10], and certain regimens (e.g., S-1 + cisplatin + GM, S-1 + GM, GM + cisplatin, nanoparticle albumin-bound-paclitaxel + cisplatin + GM and capecitabine) are considered to be useful[1,10,40-42].Considering the frequency of early recurrence and/or metastases, the timing of surgery and use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy may need to be re-evaluated.Aggressive adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered[10], and surgical resection of metastases and/or recurrences may offer a better chance of long-term survival in select patients[18].As other physicians have previously documented[1,2,4,7,8,10,21], standard therapeutic strategies need to be established for advanced GBC.

Here, we reviewed the main literature in this field[20,43-71], and crucial remarks in each are summarized in Table 5.The highest volume center in Japan is Nagoya University (Nagoya, Japan), and they continuously documented their decennial results[14,18,20,22,51,72-75].Also, we analyzed the existing guidelines in Europe (in 2017)[76,77], United States (in 2019)[78]and Japan (in 2019)[79]in detail.Especially for a comparison purpose, important comments on therapeutic strategies for GBCs in each guideline are summarized in Table 5.Central inferior bisegmentectomy (i.e., hepatectomy of segments 4b and 5) is suitable for GBC[80-82], although we employed radical or extended cholecystectomy.Skillful surgeons conversed on the topic of minimally invasive approaches to GBC[83-87], and we all may have to focus on these advanced manipulations in the near future.

This study was as a comparative, observational and retrospective study performed at a single institution, and our sample size was small.Also, this study was not a randomized controlled trial.Accordingly, we cannot rule out bias and other potential limitations.Of course, we understood that our study’s conclusions must be interpreted with extreme caution.However, we hope this report will inform the management of GBCs in future patients.

In conclusion, even in the current era, the survival of GBC patients remains unacceptable.Improved therapeutic strategies, including neoadjuvant chemotherapy, optimal surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy, should be developed to better treat patients with advanced GBC.

Table 5 Important literature and guidelines

EHBD: Extrahepatic bile duct; GBC: Gallbladder cancer; LN: Lymph node.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is the most common biliary malignancy with the worst prognosis, but aggressive surgeries may improve long-term survival.

Research motivation

We evaluated our own data along with a discussion of therapeutic strategies for GBC.

Research objectives

Nineteen GBC patients who underwent surgical treatment were enrolled in this study.

Research methods

We retrospectively investigated our patients with incidentally or non-incidentally diagnosed GBC.

Research results

Suspicious or incidental GBCs at earlier stages showed excellent outcomes without the need for two-stage surgery.Lymph nodes (LNs) around the cystic duct were reliable sentinel nodes in suspicious/incidental GBCs.Extended lymphadenectomy and resection of the extrahepatic bile duct (EHBD) prevented metastases or recurrence in early-stage GBCs but not in advanced GBCs with metastatic LNs or invasion of the nerve plexus.All patients with positive surgical margins showed poor outcomes, and we may need to reconsider the indications for major hepatectomy, minimizing its use except when it is required to accomplish negative bile duct margins.There were significant differences in overall and disease-free survival between patients with stages≤ IIB and ≥ IIIA disease.The median overall survival and disease-free survival were 1.66 and 0.79 years, respectively.

Research conclusions

Outcomes for GBC patients remain unacceptable.

Research perspectives

Improved therapeutic strategies should be considered for patients with advanced GBCs.

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Clinical implications, diagnosis, and management of diabetes in patients with chronic liver diseases

- Biomarkers for hepatocellular cancer

- Comprehensive review of hepatotoxicity associated with traditional Indian Ayurvedic herbs

- N-acetylcysteine and glycyrrhizin combination: Benefit outcome in a murine model of acetaminopheninduced liver failure

- Transaminitis is an indicator of mortality in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study

- Clinical efficacy of direct-acting antiviral therapy for recurrent hepatitis C virus infection after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma