Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin is tolerable and effective even in elderly patients 75-years-old and over

2021-01-13HideyukiTamaiNaokiShingakiYoshiyukiIdaRyoShimizuShuyaMaeshimaJunpeiOkamuraAkiraKawashimaTaiseiNakaoTakeshiHaraHiroyoshiMatsutaniIzumiNishikawaKatsuhikoHigashi

Hideyuki Tamai, Naoki Shingaki, Yoshiyuki Ida, Ryo Shimizu, Shuya Maeshima, Junpei Okamura, Akira Kawashima, Taisei Nakao, Takeshi Hara, Hiroyoshi Matsutani, Izumi Nishikawa, Katsuhiko Higashi

Hideyuki Tamai, Naoki Shingaki, Department of Hepatology, Wakayama Rosai Hospital, Wakayama 6408505, Japan

Yoshiyuki Ida, Ryo Shimizu, Shuya Maeshima, Second Department of Internal Medicine, Wakayama Medical University, Wakayama 6418509, Japan

Junpei Okamura, Akira Kawashima, Taisei Nakao, Department of Internal Medicine, Naga Municipal Hospital, Wakayama 6496414, Japan

Takeshi Hara, Department of Gastroenterology, Wakayama Rosai Hospital, Wakayama 6408505, Japan

Hiroyoshi Matsutani, Izumi Nishikawa, Katsuhiko Higashi, First Department of Internal Medicine, Hidaka General Hospital, Wakayama 6440002, Japan

Abstract

Key Words: Hepatitis C virus; Genotype 2; Sofosbuvir; Ribavirin; Elderly patients; Cirrhosis

INTRODUCTION

Although interferon (IFN)-based therapy was standard for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection for many years, clinical trials of IFN-free direct-acting antiviral agent (DAA) regimens using sofosbuvir and ribavirin for patients with genotype 2 HCV have been reported from Western countries since 2013[1-3].Those clinical trials demonstrated higher viral eradication rates and lower discontinuation rates than IFN-based therapies, and treatment-related health-related quality of life impairment during treatment was reportedly mild in these clinical trials[4].However, patients ≥ 75-yearsold were not included in the sofosbuvir plus ribavirin regimen of those clinical trials.In May 2015, clinical use of combination therapy comprising sofosbuvir and ribavirin was approved as the first IFN-free therapy for patients infected with genotype 2 HCV in Japan[5].This therapy was well tolerated and achieved a high sustained virological response (SVR) rate of 96% in a Japanese Phase III trial.However, patients ≥ 75-yearsold were again not included in that trial.The safety and effectiveness of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for elderly patients ≥ 75-years-old has thus remained unclear.

In real-world settings, elderly patients ≥ 75-years-old represent a substantial and growing population and carry a high risk of advanced liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).These patients should be treated as soon as possible.However, ribavirin has various specific side effects that affect tolerability, such as hemolytic anemia, fatigue, cough, depression, and chest pain[6,7], whereas sofosbuvir is tolerable with minimal adverse effects[8].In our previous study of lowdose pegylated IFN plus ribavirin therapy for elderly and/or cirrhotic patients infected with HCV genotype 2, drug dose reduction or interruption rates among nonelderly cirrhotic patients, elderly noncirrhotic patients, and elderly cirrhotic patients were all relatively high (65%, 63%, and 77%, respectively)[9].A high risk of ribavirin dose reduction or interruption and lower effectiveness in elderly patients can thus be expected even with sofosbuvir plus ribavirin therapy.To evaluate the realworld safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for elderly patients ≥ 75-yearsold compared to nonelderly patients, we conducted a post-marketing prospective cohort study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This was a multicenter prospective cohort study.Between June 2015 and June 2017, all patients at Wakayama Medical University Hospital, Naga Municipal Hospital, Hidaka General Hospital, and Wakayama Rosai Hospital who were eligible were enrolled in the present study.The inclusion criterion was infection with HCV genotype 2.Exclusion criteria were any of following: (1) Infection with genotypes other than genotype 2; (2) Hemoglobin concentration < 10 g/dL; (3) Estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2; (4) Decompensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class B or C); and (5) Any form of cancer.However, patients who had received curative cancer treatments were not excluded from this study.Therefore, patients with HCC who had undergone surgical resection or ablation therapy were included in this study.

Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed clinically from liver biopsy or imaging studies such as ultrasonography, contrast-enhanced computed tomography, and/or magnetic resonance imaging using morphological signs of cirrhosis from portal hypertension, such as portosystemic shunt or hypersplenism.Sample size for the present study was determined by practicability but was planned to exceed the number of patients analyzed in the Japanese phase III trial[5].All study protocols were approved by the ethics committees of the participating hospitals.Written informed consent was obtained from all patients included in this study.The present study was registered on the University Hospital Medical Information Network (trial ID: 000023269).

Treatment regimens

Standard approved doses of 400 mg sofosbuvir (Sovardi, Gilead, TKY, Japan) plus ribavirin (Copegus, Chugai Pharmaceutical, TKY, Japan or Rebetol, MSD, TKY, Japan) adjusted by body weight (1000 mg/d for patients weighing > 80 kg, 800 mg/d for patients weighing ≤ 80 but ≥ 60 kg, and 600 mg/d for patients weighing < 60 kg) were orally administered for 12 wk.If hemoglobin level fell to < 10 g/dL, ribavirin dose was reduced to 200 mg/d, and if hemoglobin level fell to < 8.5 g/dL, ribavirin was discontinued.If the attending physician judged this treatment as difficult to continue due to adverse events, both sofosbuvir and ribavirin were discontinued.

Laboratory test

HCV-RNA load was measured using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (COBAS TaqMan PCR assay version 2; Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ, United States).HCV genotype was determined using the antibody serotyping method (SRL, TKY, Japan).HCV serotypes 1 and 2 correspond to genotypes 1a/1b and 2a/2b, respectively.When HCV serotype could not be determined, genotype was examined using real-time polymerase chain reaction assay (BML, TKY, Japan).HCVRNA was checked on the day of therapy initiation and every 4 wk during treatment.Biochemical analyses including blood cell counts, C-reactive protein level, blood sugar level, and liver and renal function tests were performed every 2 wk during treatment.

Assessment of effectiveness

Rapid virological response (RVR) was defined as serum HCV-RNA negativity in week 4 after therapy initiation.End-of-treatment response was defined as serum HCV-RNA negativity in week 12 after therapy initiation.SVR was defined as HCV-RNA negativity at 24 wk after the end of therapy.The primary end point of this study was SVR at 24 wk after the end of therapy.Treatment failure was defined as non-SVR.

Assessment of safety and tolerability

Patients were assessed for the safety and tolerability of treatment by attending physicians who monitored adverse events and laboratory parameters such as blood cell counts and liver and renal function tests every 2 wk.Adverse events were assessed according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0.The incidence of and reasons for therapy discontinuation or interruption due to adverse events were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Therapeutic efficacy was evaluated using an intention-to-treat analysis.The Mann-WhitneyUtest or thet-test was used to analyze continuous variables.Fisher’s exact test or the chi-square test was used to analyze categorical variables.Logistic regression analysis for univariate comparisons was performed to investigate factors contributing to SVR.When multiple factors were significant from univariate analyses, multivariate analysis was also performed to identify independent factors.Values ofP< 0.05 were considered statistically significant.SPSS for Windows version 24J statistical software (SPSS, TKY, Japan) was used for all data analyses.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of patients

A total of 265 patients met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were enrolled in the present study.Although one patient discontinued treatment due to an adverse event, all enrolled patients completed follow-up for evaluation of safety and effectiveness.Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.Median age was 68-years-old (range, 17-86 years), and the cohort was comprised of 150 male and 115 female patients.Patients ≥ 75-years-old, cirrhotic patients, patients with moderate chronic kidney disease (defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), patients with a history of HCC treatment, and patients with a history of pegylated IFN plus ribavirin therapy accounted for 31%, 34%, 20%, 12%, and 15%, respectively.Median baseline hemoglobin level was 13.6 g/dL (range, 10.2-20.1 g/dL).

Comparison of pre-treatment factors between patients ≥ 75-years-old and < 75-years-old

A comparison of pre-treatment factors between patients ≥ 75-years-old and < 75-yearsold is shown in Table 2.Significant differences were seen in height, weight, body mass index, cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, history of HCC treatment, white blood cells, hemoglobin, platelets, alanine aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl transferase, alphafetoprotein (AFP) levels, and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

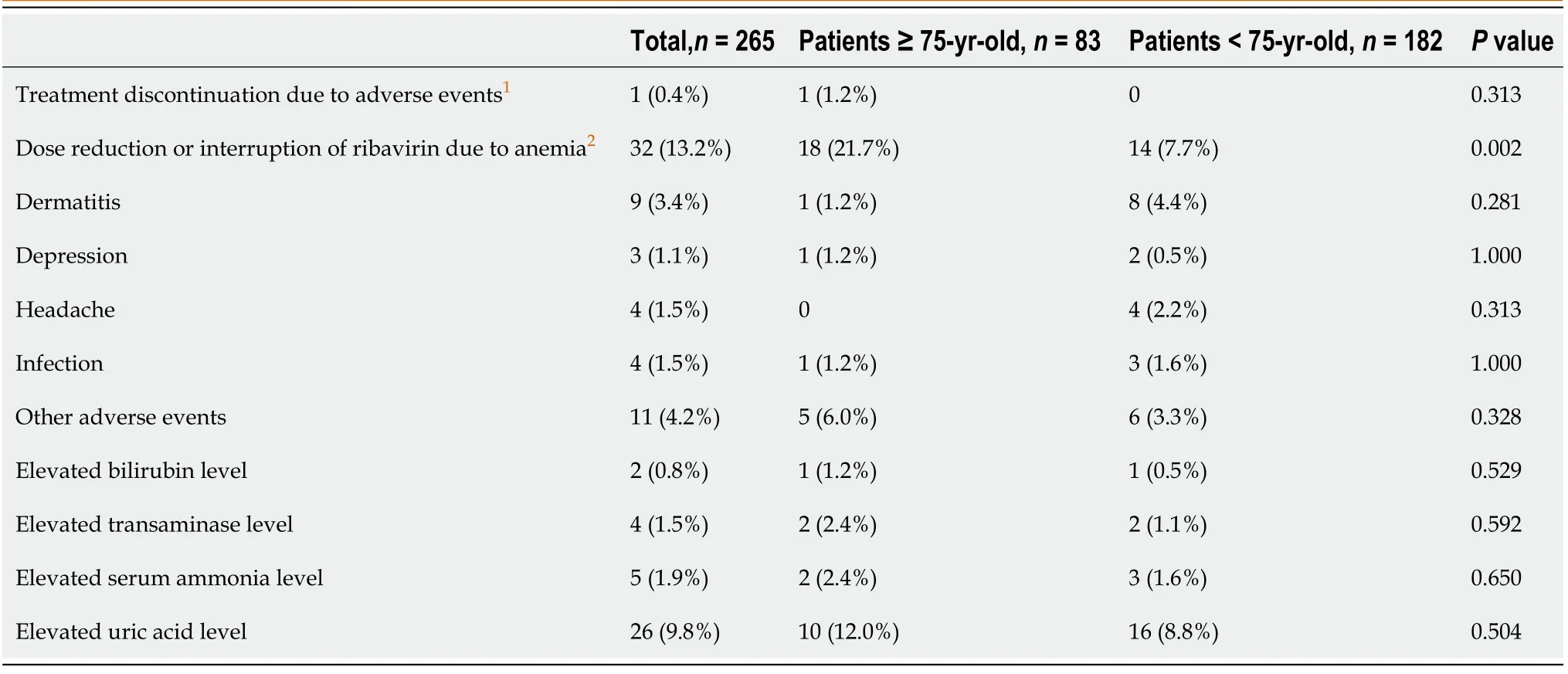

Treatment response

SVR rates overall and according to age groups are shown in Figure 1.SVR rates for the overall cohort, patients < 65-years-old, patients ≥ 65-years-old but < 75-years-old, and patients ≥ 75-years-old were 97% (258/265), 98% (93/95), 97% (84/87), and 98% (81/83), respectively.No significant differences were observed among age groups (P= 0.842).

A comparison of the viral negativity rate between patients ≥ 75-years-old and < 75-years-old during treatment is shown in Figure 2.RVR rates for patients ≥ 75-years-old and < 75-years-old groups were 84% and 89%, respectively.Although RVR rate tended to be higher in patients ≥ 75-years-old than in patients < 75-years-old, the difference was not significant (P= 0.266).End-of-treatment response rates of patients ≥ 75-yearsold and < 75-years-old were 99% and 100%, respectively.No significant difference was apparent between groups (P= 1.000).

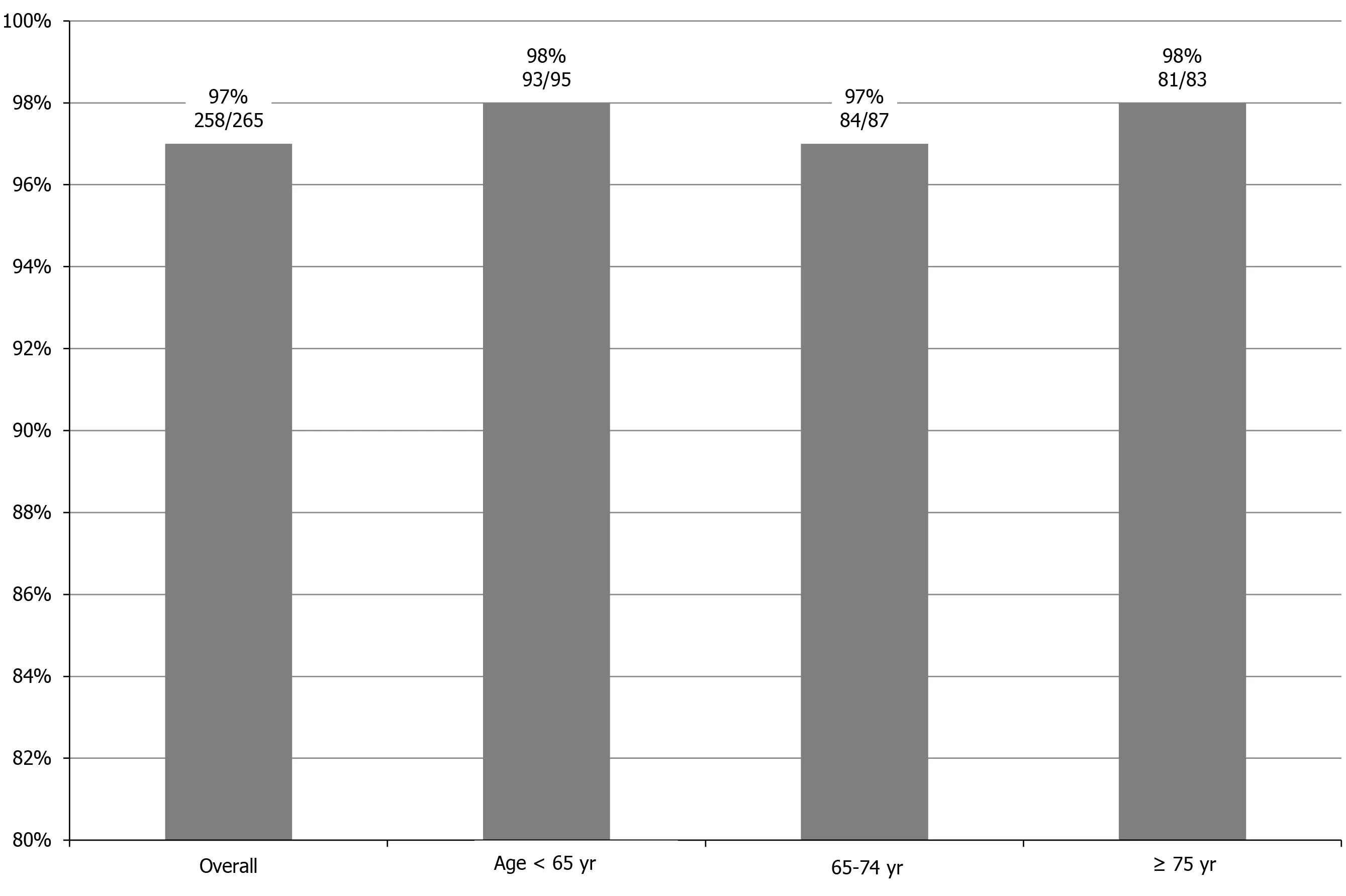

SVR rates according to background factors are summarized in Figure 3.Although no significant difference was seen in comparisons of SVR rates according to sex, cirrhosis, elderly cirrhosis, IFN plus ribavirin therapy, anemia (hemoglobin < 12 g/dL), or chronic kidney disease, a significant difference was seen between patients with and without a history of HCC treatment (P= 0.004).In patients ≥ 75-years-old with a history of IFN plus ribavirin therapy, all patients achieved SVR (100%; 14/14).In patients ≥ 75-years-old with cirrhosis, the SVR rate was 98% (40/41).

Factors contributing to SVR

Results of logistic regression analysis to investigate factors contributing to SVR are shown in Table 3.On univariate analyses, a history of HCC treatment and AFP were factors significantly contributing to SVR.Multivariate analyses revealed AFP as the only factor independently associated with SVR.

Table 1 Patient characteristics

Treatment failure

Non-SVR was shown in seven patients (3%).Factors between patients with and without SVR are compared in Table 4.When drug adherence was defined as a percentage of the actual administered dose to the planned dose, RVR adherence was not identified as significantly related to non-SVR.History of HCC treatment was the only factor significantly related to non-SVR.

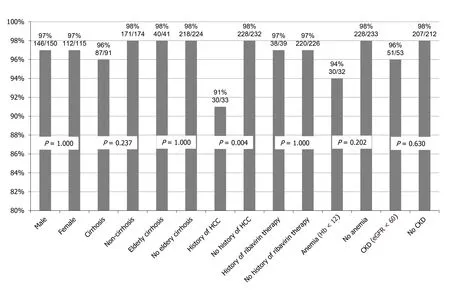

Safety and tolerability

The discontinuation rate due to adverse events was 0.4% (1/256).The reason for discontinuation was drug-induced pneumonitis with positive results for sofosbuvir on drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation testing.Adverse event profiles for the overall cohort, patients ≥ 75-years-old, and patients < 75-years-old are shown in Table 5.The most frequent adverse event other than anemia was elevated uric acid level (Grade 1).No severe liver injury or exacerbation of renal dysfunction was seen.A similar safety profile was observed between patients ≥ 75-years-old and < 75-years-old, except for ribavirin dose reduction or interruption due to anemia.Median ribavirin adherence was significantly lower for patients ≥ 75-years-old (96.8%) than for patients < 75-yearsold (100%,P= 0.001).Ribavirin dose reduction or interruption was required in 12.1% (32/265) of patients because of anemia, and anemia appeared in 7.7% (14/182) of patients < 75-years-old, and 21.7% (18/83) of patients ≥ 75-years-old.A significant difference in ribavirin dose reduction or interruption rate was also seen between groups (P= 0.002).

Table 2 Comparison of pre-treatment factors between patients ≥ 75-years-old and < 75-years-old

DISCUSSION

This was a multicenter post-marketing prospective cohort study of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin therapy for patients infected with genotype 2 HCV in a real-world clinical setting.In the present study, 31% of patients were ≥ 75-years-old, and 12% had a history of HCC treatment.Furthermore, 34% of enrolled patients had cirrhosis, and 20% had moderate chronic kidney disease.

Although some real-world data based on post-marketing cohort studies of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin have been reported, few reports have evaluated safety and efficacy for patients ≥ 75-years-old.Regarding safety, Ogawaet al[10]indicated that the frequency of adverse effects was higher for a ≥ 65-year-old group (18.9%) than for the < 65-year-old group (4.3%,P< 0.001).However, discontinuation of all drugs was required for only 3 of the 446 patients (0.7%)[10].Atsukawaet al[11]indicated that the incidence of anemia increased significantly with age, and ribavirin dose reduction rate increased sharply in patients > 70-years-old[11].Anemia during treatment occurred in 10.6% (23/218) of patients < 75-years-old, and in 48.1% (25/52) of patients ≥ 75-yearsold[11].However, none of those 270 patients discontinued use of either ribavirin or sofosbuvir[11].In the present study, although dose reduction or interruption of ribavirin due to anemia was required in 21.7% of patients ≥ 75-years-old and 7.7% of patients < 75-years-old, treatment discontinuation was required for only one patient (0.4%).Therefore, although careful monitoring of anemia and ribavirin dose adjustment is necessary to avoid discontinuation of therapy, this treatment appears tolerable even in patients ≥ 75-years-old.

Regarding efficacy, Nishidaet al[12]reported that although the difference was not significant, patients ≥ 75-years-old tended to show a lower SVR rate than patients < 75-years-old (81.3%, 13/16 for patients ≥ 75-years-old; 96.0%, 24/25 for patients < 75-years-old)[12].Atsukawaet al[11]showed SVR rates of 98.1% (51/51) for patients ≥ 75-years-old and 96.8% (211/218) for patients < 75-years-old (P= 0.999)[11].Ogawaet al[10]reported that although SVR12 was achieved by 95% (69/73) of patients > 75-years-old, the SVR12 rate was significantly lower in cirrhotic patients > 75-years-old with a history of IFN treatment (73.3%, 11/15) than in noncirrhotic patients > 75-years-old (100%, 17/17;P< 0.01)[10].In the present study, the SVR rate of patients ≥ 75-years-old was 98% (81/83).Among patients ≥ 75-years-old with a history of IFN plus ribavirin therapy, the SVR rate was 100% (14/14).Furthermore, the SVR rate of cirrhotic patients ≥ 75-years-old was also extremely high (98%, 40/41).From these results, a high SVR rate (> 95%) would be expected even in patients ≥ 75-years-old, irrespective of cirrhosis or history of IFN treatment.

Table 3 Uni- and multivariate analyses of pre-treatment factors contributing to sustained virological response

Discontinuation of pharmacotherapy[13], history of HCC[10,13], cirrhosis (advanced fibrosis)[10,14,15], renal dysfunction[16], history of IFN-based treatment[10,15], lower serum albumin, and ribavirin dose at baseline[14]have all been reported as factors associated with non-SVR of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin.Hirosawaet al[13]indicated that the risk factor most strongly associated with non-SVR was a history of HCC treatment (odds ratio: 9.29)[13].In the present study, a history of HCC treatment and AFP were factors significantly associated with SVR on univariate analysis, and AFP was the only independent factor on multivariate analyses.High serum AFP levels in patients without HCC have been associated with advanced liver fibrosis and a risk of HCC occurrence[17,18].Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin might thus be less effective in cases showing advanced liver fibrosis.Patients with a history of HCC treatment or high AFP level should probably be treated using some other ribavirin-free DAA therapy.

In recent HCV treatment guidelines from Western countries, sofosbuvir plus ribavirin therapy is no longer recommended because of the adverse effects of ribavirin and the relatively lower SVR rate compared to other DAA therapies[14,19,20].In fact, the real-life SVR rate from nationwide German data was lower compared to SVR rates of clinical trials (83% in intention-to-treat analysis)[21].Recently, ribavirin-free DAA therapies such as glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir, and sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir have also been approved for use in patients with HCV genotype 2 in Japan[22,23].These therapies have shown no adverse effects due to ribavirin and have thus become firstline treatments.These therapies also represent rescue treatments for patients with sofosbuvir plus ribavirin failure.However, in consensus statements and recommendations on the treatment of hepatitis C from the Asian-Paci c Association for the Study of the Liver, sofosbuvir plus weight-based ribavirin for 12 wk is recommended as a first-line treatment, and ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 12 wk is recommended for treatment-naïve HCV genotype 2 patients who cannot tolerate ribavirin[24].In addition, SVR rates from Asian real-world data were similar to those of the phase III trial[25].Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin therapy offers advantages in terms of both cost and real-world evidence.

Table 4 Comparison of factors between patients with and without sustained virological response

Some limitations need to be considered for the present study.First, some selection biases would be present.Second, the number of patients may not have been sufficient to reach definitive conclusions regarding safety and effectiveness in patients ≥ 75-years-old.Third, reasons for failure of this therapy could not be clarified by our analysis because the number of patients who did not achieve SVR was too small.Furthermore, sofosbuvir-specic resistance-associated substitutions (RASs) were not tested for in this study.The prevalence of the naturally occurring RAS·S282T, as the only known variant conferring sofosbuvir resistancein vitro, is reportedly rare in genotype 2 (0.22%)[26].However, RAS·A150V has recently been found to be associated with reduced response to treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin and has appeared in genotype 2a (13.8%) and genotype 2b (1.03%)[26].In addition, the naturally occurring nucleoside inhibitor-specific RASs (E237G, M289I/L, L320 F, and V321A/I) are also found in genotype 2[26].The influence of these preexisting RASs on SVR should be analyzed using a larger number of cases with treatment failure.

Table 5 Adverse events during treatment

Figure 1 Sustained virological response rates according to age groups.

Sofosbuvir and ribavirin represent an acceptable and effective treatment even for patients ≥ 75-years-old in a real-world setting.An extremely high SVR rate can be achieved when adequate management for adverse effects is performed to avoid discontinuation of treatment, irrespective of age.

Figure 2 Comparison of viral negativity rates between patients ≥ 75-years-old and < 75-years-old during treatment.

Figure 3 Sustained virological response rates according to background factors.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

In real-world settings, elderly patients infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) represent a substantial and growing population and carry a high risk of advanced liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.Therefore, these patients should be treated as soon as possible.Clinical trials of interferon-free direct-acting antiviral agent regimens using sofosbuvir and ribavirin for patients with genotype 2 HCV have been reported since 2013.However, patients ≥ 75-years-old were not included in the sofosbuvir plus ribavirin regimen of those clinical trials.The safety and effectiveness of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for elderly patients ≥ 75-years-old has thus remained unclear.

Research motivation

In recent HCV treatment guidelines from Western countries, sofosbuvir plus ribavirin therapy is no longer recommended because of the adverse effects of ribavirin and the relatively lower sustained viral response (SVR) rate compared to other direct-acting antiviral agent therapies.However, in consensus statements and recommendations on the treatment of hepatitis C from the Asian-Pacic Association for the Study of the Liver, sofosbuvir plus weight-based ribavirin for 12 wk is recommended as a first-line treatment, and SVR rates from Asian real-world data were similar to those of the phase III trial.Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin therapy also offers advantages in terms of both cost and real-world evidence.The real-world safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for elderly patients ≥ 75-years-old can provide useful information regarding treatment strategy for elderly patients with HCV in the Asia-Pacific region.

Research objectives

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the real-world safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for elderly patients ≥ 75-years-old compared to non-elderly patients

Research methods

This is a multicenter post-marketing prospective cohort study of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin therapy for patients infected with genotype 2 HCV in a real-world clinical setting.We treated 265 patients with genotype 2 HCV using standard approved doses of sofosbuvir (400 mg/d) plus ribavirin adjusted by body weight, administered orally for 12 wk.In the present study, 31% of patients were ≥ 75-years-old, and 12% had a history of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treatment.Furthermore, 34% of enrolled patients had cirrhosis, and 20% had moderate chronic kidney disease.The primary end point of the present study was SVR at 24 wk after the end of therapy.

Research results

Regarding efficacy, SVR rates for the overall cohort, patients < 65-years-old, ≥ 65-years-old but < 75-years-old, and ≥ 75-years-old were 97% (258/265), 98% (93/95), 97%(84/87), and 98% (81/83), respectively (P = 0.842).Among patients ≥ 75-years-old with a history of interferon plus ribavirin therapy, the SVR rate was 100% (14/14).Furthermore, the SVR rate of cirrhotic patients ≥ 75-years-old was also extremely high(98%, 40/41).From these results, a high SVR rate (> 95%) would be expected even in patients ≥ 75-years-old, irrespective of cirrhosis or history of interferon treatment.Logistic regression analyses identified history of HCC treatment and alpha-fetoprotein as factors significantly associated with SVR.SVR rate was significantly lower for patients with HCC treatment (91%) than for patients without history of HCC treatment(98%, P = 0.004).Regarding safety, although dose reduction or interruption of ribavirin due to anemia was required in 21.7% of patients ≥ 75-years-old and 7.7% of patients <75-years-old, treatment discontinuation was required for only one patient (0.4%).Therefore, this treatment appears tolerable even in patients ≥ 75-years-old.

Research conclusions

Sofosbuvir and ribavirin represent an acceptable and effective treatment even for patients ≥ 75-years-old in a real-world setting.An extremely high SVR rate can be achieved when adequate management for adverse effects is performed to avoid discontinuation of treatment, irrespective of age.

Research perspectives

Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin might be less effective in patients with a history of HCC treatment or high alpha-fetoprotein level, irrespective of age.These patients should probably be treated using some other ribavirin-free direct-acting antiviral agent therapy.

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Clinical implications, diagnosis, and management of diabetes in patients with chronic liver diseases

- Biomarkers for hepatocellular cancer

- Comprehensive review of hepatotoxicity associated with traditional Indian Ayurvedic herbs

- N-acetylcysteine and glycyrrhizin combination: Benefit outcome in a murine model of acetaminopheninduced liver failure

- Transaminitis is an indicator of mortality in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study

- Clinical efficacy of direct-acting antiviral therapy for recurrent hepatitis C virus infection after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma