基于微卫星标记的真鲷放流群体与增殖海域群体遗传变异比较分析

2020-11-06孙典荣单斌斌杨长平周文礼

赵 雨, 孙典荣, 单斌斌, 刘 岩, 杨长平, 周文礼

基于微卫星标记的真鲷放流群体与增殖海域群体遗传变异比较分析

赵 雨1, 2, 孙典荣2, 单斌斌2, 刘 岩2, 杨长平2, 周文礼1

(1. 天津农学院 水产学院, 天津 300384; 2. 中国水产科学院 南海水产研究所 农业农村部南海渔业资源开发利用重点实验室, 广东 广州 510300)

真鲷()是中国沿岸海域重要的经济种类, 增殖放流作为修复真鲷渔业资源、恢复自然群体的方法, 现已在中国被广泛地应用。然而, 将大量人工繁育的苗种投入自然海域中, 可能会对自然群体造成一定程度的遗传学影响。因此, 在开展真鲷增殖放流的同时, 应进行遗传监测。本研究使用7对真鲷微卫星标记, 对2017年于防城港沿岸海域开展的真鲷增殖放流进行遗传监测, 对比分析了真鲷亲体、放流真鲷苗种以及放流后混合群体的遗传多样性。研究结果表明, 真鲷亲本群体与真鲷放流群体的等位基因丰度(13.525 3, 16.428 6)和期望杂合度(0.792 7, 0.814 5)没有明显的差异, 表明在苗种繁育过程中, 没有出现遗传多样性丢失的现象。真鲷放流群体和放流后混合群体的期望杂合度(0.814 5, 0.822 8)、等位基因丰度(16.428 6, 16.755 5)相似, 表明真鲷放流群体和放流后混合群体处于相同的遗传多样性水平。3个群体的多态信息含量为0.768 8~0.805 5, 表明3个群体均具有较高的遗传多样性。群体间遗传分化指数(0.016 667)和遗传距离(0.265 375~0.301 915)的结果显示群体间的遗传分化微弱, 未形成明显的遗传分化。因此, 可认为本研究中真鲷增殖放流未对放流后混合群体造成明显的遗传学影响。本研究为今后真鲷增殖放流遗传监测提供了理论参考依据。

真鲷(); 微卫星; 遗传影响; 增殖放流

真鲷()隶属于鲈形目(Perciformes)、鲈亚目(Percoidei)、鲷科(Sparidae), 俗称红加吉(Red Sea bream), 分布于印度洋和太平洋西部近海, 在中国由北至南近岸海域均有分布, 是中国名贵经济鱼类和海水养殖的重要对象[1]。

20世纪50年代, 由于中国对真鲷资源的不合理开发与利用, 且缺乏对真鲷资源的有效保护, 导致资源严重匮乏且短时间内难以恢复[2]。为增加真鲷资源, 满足市场需求, 中国在20世纪80年代末开始进行真鲷的增殖放流活动[3]。20世纪70年代~90年代真鲷苗种人工繁育与养殖的成功也为增殖放流提供了极大的便利[4]。1990年, 中国与日本合作, 在山东省5处放流地点共放流真鲷苗种73 024尾[5]。1991年~ 1995年间, 在渤海放流真鲷苗种90多万尾[6]。此后放流量不断增加, 改善了真鲷资源状况[7-8]。近年来, 中国真鲷的增殖放流也在不断进行。东山县在2018年6月和2019年6月分别放流真鲷苗种25.8621万尾和23.2558万尾[9-10]。石狮市于2018年在深沪湾梅林码头附近海域放流真鲷31万尾[11]。嵊泗县也于2019年6月进行了真鲷的增殖放流[12]。

然而, 将大量人工繁育的苗种投入自然海域中, 可能会对自然群体造成一定程度的遗传学影响[13-14]。放流群体不仅会与野生群体争夺食物与生存空间[15], 还因其与野生群体存在的遗传差异, 与自然群体产生的后代发生基因交流, 进而影响其遗传多样性和遗传结构[16]。有研究表明, 增殖放流会对自然群体造成遗传学影响, Perez-Enriquez[17]等利用3个微卫星对日本四国岛周边7个地点的真鲷群体开展研究, 以探究真鲷增殖放流对自然群体造成的遗传学影响, 结果显示放流后增殖海域内的自然群体与邻近海域的自然群体存在一定程度遗传差异。Kitada[18]等通过遗传监测结合40 a时间的渔获数据, 评估了长期的增殖放流对日本鹿儿岛湾的真鲷野生种群的大小和遗传多样性造成的影响, 其分析发现, 增殖放流降低了该地真鲷种群的遗传多样性, 但随着野生种群规模的增大, 遗传效应逐渐减弱, 并提出, 除非采取有效的措施控制捕捞量并恢复自然栖息地, 否则从长远来看, 为加强和保护种群而进行的增殖放流的作用十分有限。Gonzalez[19]等通过研究广岛湾5个地点的黑鲷()发现, 最高放流强度地点的黑鲷拥有最少的等位基因且与其中3个地点的群体遗传分化显著, 表明增殖放流对广岛湾黑鲷的遗传多样性造成了重要影响。Shan[20]等基于线粒体控制区的序列对珠江口的黑鲷增殖放流进行了研究, 结果显示放流后珠江口种群的遗传多样性低于其他野生种群, 黑鲷的放流可能影响了珠江口野生种群的遗传多样性。相反, Katalinas[21]等利用微卫星对1999年~2011年间在南卡罗莱纳进行的美国红鱼()的增殖放流进行了评估, 结果显示放流并未对美国红鱼野生群体遗传多样性产生影响。Ozerov[22]等也利用微卫星和SNPs评估了16 a间因增殖放流对芬兰湾和波罗的海的大西洋鲑鱼()野生种群的遗传影响, 结果表明大西洋鲑鱼的增殖放流增加了野生种群的等位基因丰富度, 但改变了其种群结构。遗传学分析可以帮助划定鱼类种群的边界、了解种群的健康和大小, 并向管理人员提供放流的参考信息[23], 因此应对野生群体进行遗传监测, 以为渔业管理和增殖放流提供科学依据。

微卫星以其广泛分布、含量丰富, 多态性高等优点, 现已发展成为一种被广泛应用的分子标记技术[24-26]。本研究利用微卫星序列作为分子标记, 对在防城港沿岸海域开展的真鲷增殖放流进行遗传监测, 以期阐明其群体遗传多样性和遗传结构现状, 为真鲷的资源保护及合理的开发提供基础资料和科学依据。

1 材料与方法

1.1 样品采集

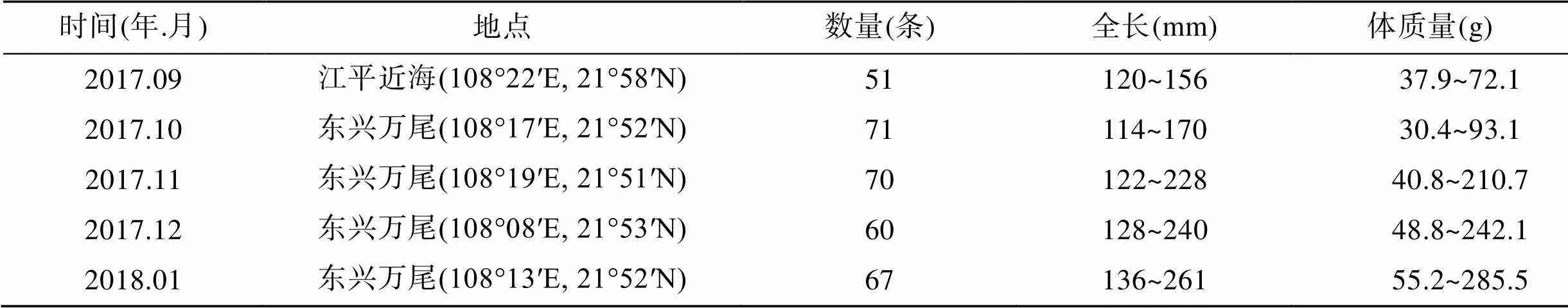

真鲷亲体采自北海广西海洋研究所养殖基地; 放流群体(子代群体)为真鲷亲体繁育后所得后代; 2017年5月, 在防城港沿岸海域(108°05′E, 21°55′N)进行增殖放流, 共放流体长为3.7~5.8 cm的真鲷苗种12.27万尾; 放流后, 于2017年9月~2018年1月进行采样调查,回捕真鲷样品(表1)。所有样品经传统形态学测量后, 取鱼体背部肌肉组织于95%乙醇中保存, 以备后续实验。

表1 真鲷回捕信息

1.2 基因组DNA提取

取276尾真鲷亲体、98尾放流真鲷以及294尾回捕真鲷样品肌肉组织, 严格按照海洋动物组织基因组DNA提取试剂盒(天根生化科技有限公司, 北京)中的说明书操作步骤进行DNA提取。

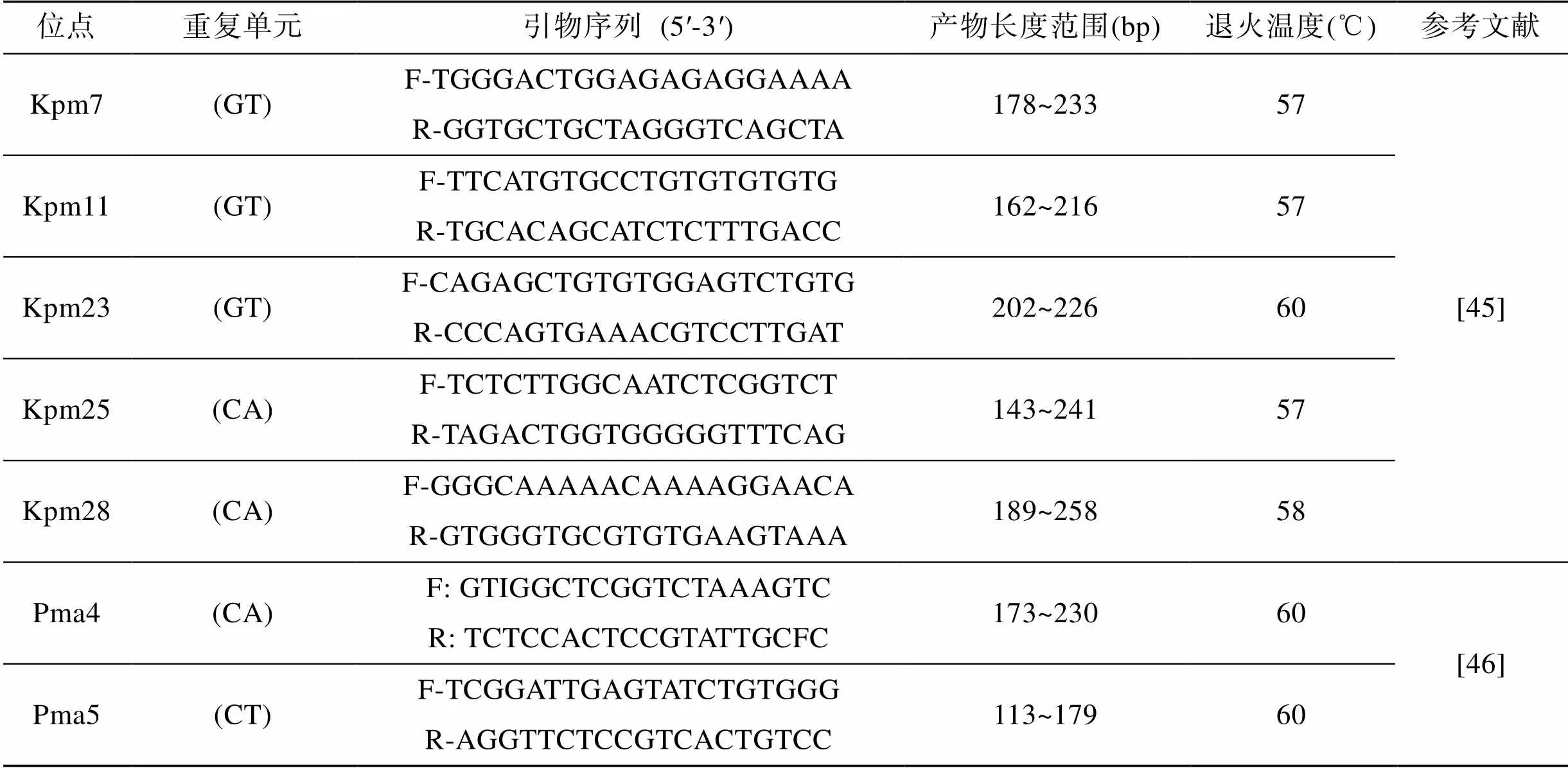

1.3 PCR扩增及测序分型

选取多态性较高的7对微卫星引物进行扩增, 每对引物的5’端分别用TAM、FAM和HEX 3种荧光标记, 具体引物信息见表2。PCR反应总体积为25 µL, 其中包括10×PCR Buffer 2.5 µL, dNTPs 2 µL, 双向荧光引物各1 µL, Taq DNA聚合酶0.15 µL, 去离子水17.5 µL。PCR反应条件为: 94℃预变性5 min; 94℃变性50 s, 在引物特定的退火温度下退火50 s, 72℃延伸1 min, 循环35次; 最后72℃延伸10 min。制备1.5%琼脂糖凝胶(含DuRed染料)对PCR产物进行电泳检测, 筛选出扩增成功的产物送至生物公司进行毛细管电泳检测, GeneMarker 2.2.0软件收集各位点等位基因数据, 然后进行人工校正。

表2 对微卫星引物的特征描述

1.4 数据分析

使用PopGene[27]软件统计每个微卫星位点的等位基因数()、观测杂合度()、期望杂合度()、多态信息含量(PIC)、有效等位基因()。使用FSTAT 2.9.3[28]软件获得其等位基因丰富度(S), 计算两两群体间遗传分化指数ST并通过1000次随机抽样检验显著性。通过GENEPOP 4.0[29]检验各位点是否符合Hardy-Weinberg平衡检验。使用Micro-Checker[30]软件检测各位点是否存在无效等位基因。此外, 使用Population 1.2计算3个真鲷群体之间的遗传距离[31]。

2 实验结果

2.1 群体遗传多样性

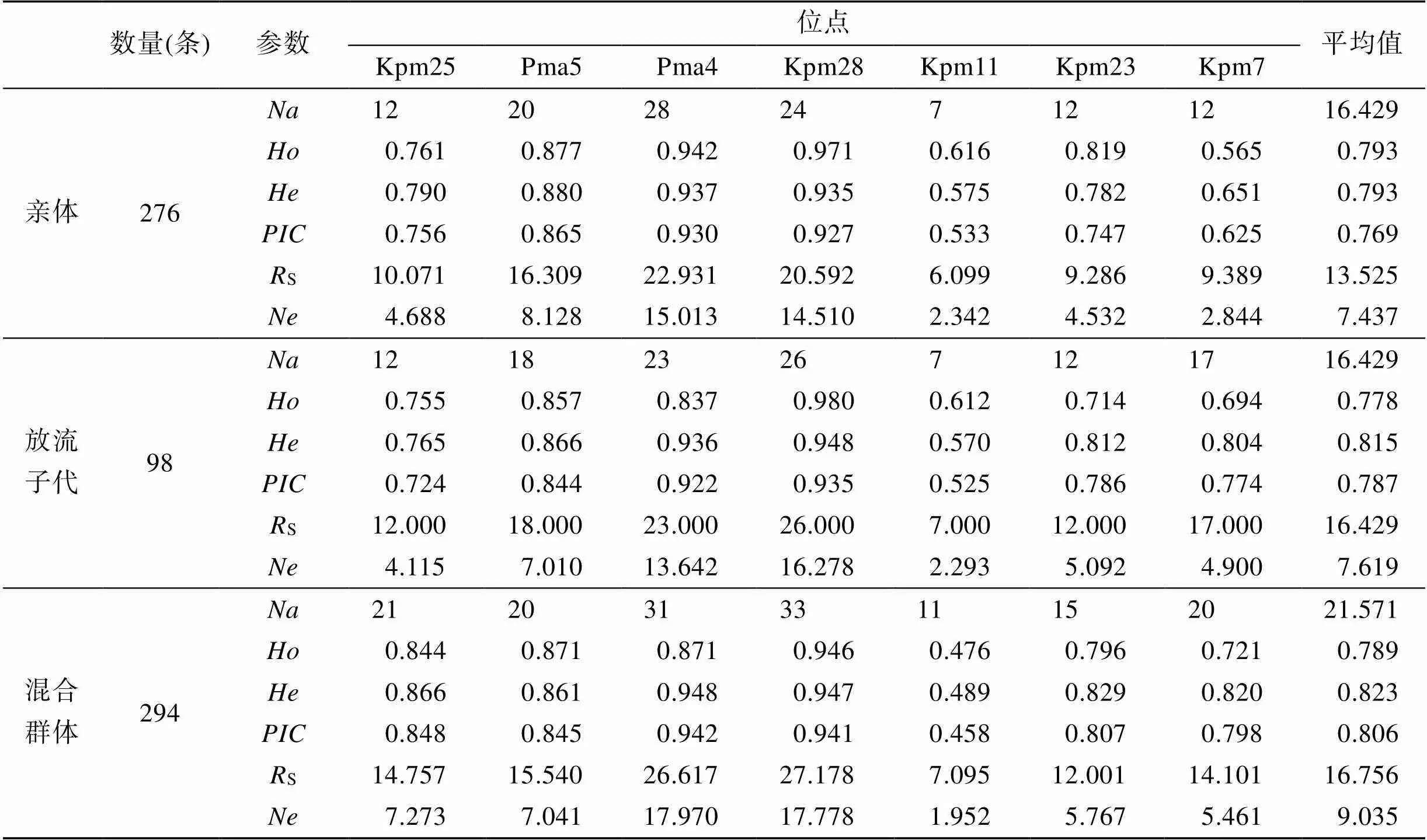

本研究的3个真鲷群体在7个微卫星位点上总等位基因数分别为115、115和151个等位基因(表3), 平均等位基因数为(16.429~21.571)。3个群体的有效等位基因数为(1.952~17.970), 均不同程度地低于其对应的等位基因数。3个群体在7个位点的平均观测杂合度为(0.778 4~0.793 0), 除真鲷亲体群体外, 均低于其平均期望杂合度, 说明群体中发生了杂合子缺失。真鲷亲本群体与真鲷放流群体的等位基因丰度(13.525 3, 16.428 6)和期望杂合度(0.792 7, 0.814 5)没有明显的差异, 表明在苗种繁育过程中, 没有出现遗传多样性丢失的现象。真鲷放流群体和放流后混合群体的期望杂合度(0.814 5, 0.822 8)、等位基因丰度(16.428 6, 16.755 5)相似, 表明真鲷放流群体和放流后混合群体处于相同的遗传多样性水平。真鲷放流群体和真鲷亲本群体分别在Pma4位点和Kpm7位点存在无效等位基因, 同时放流后混合群体在这两个位点均存在无效等位基因。3个群体的多态信息含量为0.768 8~0.805 5, 表明3个群体均具有较高的遗传多样性。使用GENEPOP4.0对3个群体的7个位点逐个进行Hardy-Weinberg平衡检验的结果显示, 真鲷亲本群体与真鲷放流群体在7个微卫星位点均符合Hardy-Weinberg平衡, 而放流后混合群体中有4个位点显著偏离平衡。

2.2 群体遗传结构

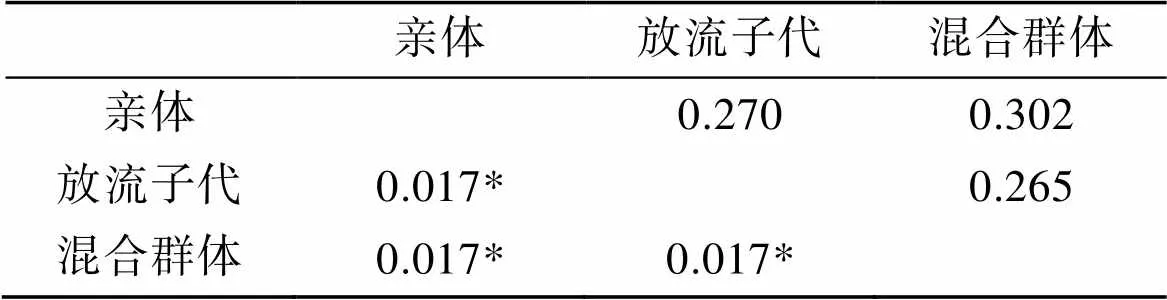

使用FSTAT 2.9.3计算的结果显示, 放流后混合群体与真鲷亲本群体、放流后混合群体与真鲷放流群体、真鲷亲本群体与真鲷放流群体的遗传分化指数ST为0.016 667, 表明两两群体间存在显著地微弱的遗传分化。计算真鲷群体间的遗传距离, 结果显示3个真鲷群体间遗传距离较小(0.265 375~ 0.301 915)(表4)。

表3 真鲷群体遗传多样性参数

表4 真鲷群体间的FST值(对角线之下)和遗传距离(对角线上)

*.<0.05

3 讨论

遗传多样性关系到种群的进化与适应, 物种对环境变化的适应能力和进化的潜力与种内遗传多样性或变异性成正比, 并以此保持物种和整个生态系统的多样性[32-33]。物种遗传多样性丧失的问题不仅在增殖放流活动中至关重要, 更因其涉及生物体对环境变化的适应性和进化反应, 在保护遗传学中受到高度重视[34]。Romo[35]等利用微卫星标记对条斑星鲽()在日本增殖放流的效果进行了评估, 结果显示放流群体与自然群体并无明显遗传差异, 该项目中增殖放流未产生消极影响。Kitada[36]等通过比较分析鹿儿岛真鲷的放流和日本北部的太平洋鲱()的放流发现, 虽然在真鲷群体和太平洋鲱群体中均出现稀有等位基因的丢失, 但放流群体对其产生的遗传影响远远小于由其生活史、环境和渔业选择压力造成的影响, 并提出增殖放流的遗传影响的大小应取决于种群的大小、放养强度、种群和放流后代的遗传多样性以及种群间的基因流动, 因此在增殖放流项目中保持种群的遗传多样性是非常重要的。Katalinas[21]等曾用微卫星研究增殖放流对南卡罗来纳河口美国红鱼()的遗传影响, 其结果并未出现遗传多样性的显著变化, 并推测可能是由于世代交叠、野生鱼类种群规模大、美国红鱼表现出相对较长的寿命等对放流产生的遗传影响起到一定的缓释作用。本文中, 有52个亲本个体在7个位点上共17个等位基因(Kpm25位点1个、Pma5位点2个、Pma4位点8个、Kpm28位点2个、Kpm11位点1个、Kpm23位点2个,Kpm7位点1个)未在子代中出现, 因此这些亲本个体并未实际参与繁殖。在子代中有24个个体在7个位点上共21个等位基因(Kpm25位点2个、Pma5位点2个、Pma4位点4个、Kpm28位点4个、Kpm11位点1个、Kpm23位点2个, Kpm7位点6个)未在亲本中出现, 推测是由于亲本未采集完全。虽然本研究的亲体样品并未包含全部亲体, 但由于样品数量充足, 可以代表亲体群体的遗传多样性与遗传结构。

等位基因丰富度、位点杂合度以及多态信息含量是反映群体遗传多样性的重要参数[37]。本研究与Gonzalez[34]等对相模湾和东京湾的真鲷群体进行的研究采用了6对相同的微卫星引物。在Kpm7(0.710~ 0.892, 0.565~0.721), Kpm23(0.822~0.845, 0.714~0.819), Kpm25(0.787~0.870, 0.755~0.844), Pma5(0.891~0.92, 0.857~0.877), Kpm11(0.469~0.712, 0.476~0.616)这5个位点上, 本研究中真鲷群体的观测杂合度略低于日本学者的研究群体, 仅在Kpm28位点上略高于日本群体(0.87~0.947, 0.946~0.980)。本研究中的3个群体在各个位点上的平均观测杂合度(0.778~0.793)、平均期望杂合度(0.793~0.823)和平均等位基因丰富度(13.525~16.756)略低于Sawayama[38]等在日本濑户内海采集的野生群体(0.952, 0.939, 17.4)和Sawayama[39]等在日本爱媛县附近采集的研究群体(0.719~0.906, 0.714~0.938, 7.0~25.3), 但总体上无明显差异, 证明本研究中的真鲷群体与日本群体处于相同的遗传多样性水平。通常, 用于繁育增殖放流苗种的亲体数量有限, 人工繁育苗种的遗传多样性较野生群体低, 被投入自然海域的放流苗种通过与野生群体之间的基因交流从而降低野生群体的遗传多样性, 因此放流苗种应尽可能减小与野生群体之间的差异[34]。Gonzalez[40]等曾用6个微卫星标记比较了广岛湾放流黑鲷与野生黑鲷的遗传多样性, 结果表明虽然群体间观察到较微弱的遗传多样性差异, 但这种对广岛湾野生种群遗传组成潜在的有害影响, 使得有必要对增殖放流的遗传效应进行定期监测。在季晓芬[41]利用13对微卫星评估草鱼增殖放流对野生群体遗传多样性影响的研究中, 虽然在石首、监利两地的放流群体为人工养殖群体, 但草鱼放流群体仍保持较高的遗传多样性, 推测是由于其苗种来源于长江。胡新艳[42]等也利用微卫星对用于放流的养殖群体遗传多样性进行了分析, 结果显示可能是由于亲代的人工选择的干扰, 导致了杂合子的缺失和过剩。在本研究中, 真鲷亲本群体与真鲷放流群体的等位基因丰度(13.5253, 16.4286)和期望杂合度(0.7927, 0.8145)没有明显的差异, 推测可能本实验在苗种繁育过程中使用了足够数量的亲本, 使得放流苗种中未发生明显的遗传多样性丢失。

群体遗传分化指数ST是利用遗传信息反映群体之间遗传分化的指标, 数值越大表明两群体间的遗传分化水平越高[40]。Wright[43]提出遗传分化指数度量标准: 0

[1] 乐小亮, 章群, 赵爽, 等. 中国近海真鲷遗传变异的线粒体控制区序列分析[J]. 广东农业科学, 2010, 2: 136-139. Yue Xiaoliang, Zhang Qun, Zhao Shuang, et al. Genetic variation of red sea bream () in coastal waters of China inferred from mitochondrial DNA control region sequence analysis[J]. Guangdong Agricultural Sciences, 2010, 2: 136-139.

[2] 陈大刚. 黄渤海渔业生态学[M]. 北京: 海洋出版社, 1991: 302-305.Chen Dagang. Fisheries Ecology of Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea[M]. Beijing: China Ocean Press, 1991: 302-305.

[3] 张斌, 李继龙, 杨文波, 等. 人工繁育真鲷苗种标志放流理论基础研究[J]. 中国渔业经济, 2010, 28(3): 94-109. Zhang Bin, Li Jilong, Yang Wenbo, et al. Assessments for impacts of red sea bream artificial releasing and enhancement[J]. Chinese Fisheries Economics, 2010, 28(3): 94-109.

[4] 柳学周, 雷霁霖, 刘忠强, 等. 真鲷()苗种生产技术的开发研究[J]. 中国水产科学, 1996, 3(1): 47-55. Liu Xuezhou, Lei Jilin, Liu Zhongqiang, et al. Studies on seed production tcehnology of red sea bream[J]. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 1996, 3(1): 47-55.

[5] 刘世禄. 黄海所“中日青岛小麦岛真鲷育苗与增殖放流”合作项目首获成功[J]. 渔业信息与战略, 1991, 12: 25-26. Liu Shilu. The cooperation project of “breeding and releasing of red sea bream from Qingdao wheat island of China and Japan” in Yellow sea fisheries research institute was successful for the first time[J]. Fishery Information & Strategy, 1991, 12: 25-26.

[6] 刘璐, 林琳, 李纯厚, 等. 海洋渔业生物增殖放流效果评估研究进展[J]. 广东农业科学, 2014, 41(2): 133-137. Liu Lu, Lin Lin, Li Chunhou, et al. Effect assessment of marine fishery stock enhancement: A review of the literature[J]. Guangdong Agricultural Sciences, 2014, 41(2): 133-137.

[7] 大连市海洋与渔业局办公室. 大连市首次进行鱼类人工增殖放流[J]. 水产科学, 2005, 24: 42. Dalian Ocean and Fishery Bureau Office. The first artificial stock enhancement of fish in Dalian[J]. Fishery Sciences, 2005, 24: 42.

[8] 邹建伟, 黄俊秀, 王强哲, 等. 南海北部湾真鲷的捕捞现状研究[J].渔业信息与战略, 2016, 31(3): 179-185. Zou Jianwei, Huang Junxiu, Wang Qiangzhe, et al. Study on fishing status ofin Beibu Gulf, South China Sea[J]. Fishery Information & Strategy, 2016, 31(3): 179-185.

[9] 东山县海洋与渔业局. 东山县海洋与渔业局关于开展真鲷增殖放流的公示[EB/OL]. (2018-06-19)[2020-03-08].http: //www.dongshandao.gov.cn/cms/html/dsxrmzf/2018- 06-19/645328494.html.Dongshan County Marine and Fishery Bureau. Public notice of Dongshan County Marine and Fishery Bureau on carrying out stocking enhancement of red sea bream[EB/OL]. (2018- 06-19)[2020-03-08].http://www.dongshandao.gov.cn/cms/ html/dsxrmzf/2018-06-19/645328494.html.

[10] 东山县海洋与渔业局. 东山县海洋与渔业局关于开展真鲷增殖放流的公示[EB/OL]. (2019-06-19)[2020- 03-08].http://www.dongshandao.gov.cn/cms/html/dsxrmzf/ 2019-06-19/1762862063.html. Dongshan County Marine and Fishery Bureau. Public notice of Dongshan County Marine and Fishery Bureau on carrying out stocking enhancement of red sea bream[EB/OL]. (2019- 06-19)[2020-03-08].http://www.dongshandao.gov.cn/cms/ html/dsxrmzf/2019-06-19/1762862063.html.

[11] 福建省海洋与渔业局. 石狮市放流31万尾真鲷鱼苗[EB/OL]. (2018-06-12)[2020-03-08].http://hyyyj.fujian. gov.cn/xxgk/hydt/jcdt/201806/t20180612_3161585.htm. Fujian Provincial Marine Fishery Bureau. 310, 000 red sea bream fry are released in Shishi City[EB/OL]. (2018- 06-12)[2020-03-08].http://hyyyj.fujian.gov.cn/xxgk/hydt/ jcdt/201806/t20180612_3161585.htm.

[12] 嵊泗县海洋与渔业局. 我县顺利举行2019年渔业资源增殖放流仪式活动[EB/OL]. (2019-06-18)[2020-03- 08]. http://www.shengsi.gov.cn/art/2019/6/18/art_1452159_ 34693414.html. Shengsi County Marine and Fishery Bureau.Our county successfully held the ceremony of fishery resources stock enhancement in 2019[EB/OL]. (2019-06-18)[2020-03-08].http://www.shengsi.gov.cn/art/2019/6/18/art_1452159_34693414.html.

[13] Norris A T, Bradley D G, Cunningham E P. Microsatellite genetic variation between and within farmed and wild Atlantic salmon () populations[J]. Aquaculture, 1999, 180(3-4): 247-264.

[14] 杨长平, 孙典荣. 南海区渔业资源增殖放流关键技术研究与示范[M]. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2019: 132-134. Yang Changping, Sun Dianrong. Research and Demonstration on Key Technologies of Fishery Resources Stock Enhancement in the South China Sea[M]. Beijing: China Agriculture Press, 2019: 132-134.

[15] Cooney R T, Brodeur R D. Carrying capacity and North Pacific salmon production: stock-enhancement implica- tions[J]. Bulletin of Marine Science, 1998, 62(2): 443-464.

[16] Sekino M, Hara M, Taniguchi N. Loss of microsatellite and mitochondrial DNA variation in hatchery strains of Japanese flounder[J]. Aquaculture, 2002, 213: 101-122.

[17] Perez-Enriquez R, Takemura M, Tabata K, et al. Genetic diversity of red sea breamin western Japan in relation to stock enhancement[J]. Fisheries Science, 2001, 67(1): 71-78.

[18] Kitada S, Nakajima K, Hamasaki K, et al. Rigorous monitoring of a large-scale marine stock enhancement program demonstrates the need for comprehensive management of fisheries and nursery habitat[J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9(1): 1-10.

[19] Gonzalez B E, Umino T. Fine-scale genetic structure derived from stocking black sea bream,(Bleeker, 1854), in Hiroshima Bay, Japan[J]. Journal of Applied Ichthyology, 2009, 25(4): 407-410.

[20] Shan B, Liu Y, Song N, et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of black sea bream () based on mitochondrial control region sequences: The genetic effect of stock enhancement[J]. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 2020: 101-188.

[21] Katalinas C J, Brenkert K, Darden T, et al. A genetic assessment of a red drum,, stock enhancement program[J]. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 2018, 49(3): 523-539.

[22] Ozerov M Y, Gross R, Bruneaux M, et al. Genomewide introgressive hybridization patterns in wild Atlantic salmon influenced by inadvertent gene flow from hatchery releases[J]. Molecular Ecology, 2016, 25(6): 1275-1293.

[23] O’Donnell T P, Denson M R, Darden T L. Genetic population structure of spotted seatroutalong the south-eastern USA[J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 2014, 85(2): 374-393.

[24] Tautz D. Hypervariability of simple sequences as a general source for polymorphic DNA markers[J]. Nucleic Acid Research, 1989, 17(16): 6463-6471.

[25] Weber J L. Human DNA polymorphisms and methods of analysis[J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 1990, 1(2): 166-171.

[26] 李莉好, 喻达辉. 基因组微卫星位点的分离方法及其在水产动物中的应用[J]. 南方水产科学, 2006, 2(5): 74-80. Li Lihao, Yu Dahui. Methods for isolating microsatellite DNA loci from genomic DNA and the applications in aquatic animals[J]. South China Fisheries Science, 2006, 2(5): 74-80.

[27] Yeh F C, Yang R C, Boyle T B J, et al. POPGENE, the user-friendly shareware for population genetic analysis[J]. Molecular Biology and Biotechnology Centre, University of Alberta, Canada, 1997, 10: 295-301.

[28] Goudet J. A program to estimate and test gene diversities and fixation indices (version 2.9.3)[EB/OL]. (2002) [2020-09-07]. http://www.unil.ch/dee/home/menuinst/ softwares/fstat. html.

[29] Rousset F. Genepop’007.a complete re-implementation of the genepop software for Windows and Linux[J]. Molecular Ecology Resources, 2008, 8: 103-106.

[30] Van Oosterhout C, Hutchinson W F, Wills D P M, et al. MICRO-CHECKER: software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data[J]. Molecular Ecology Notes, 2004, 4: 535-538.

[31] Cavalli-Sforza L L, Edwards A W F. Phylogenetic analysis: models and estimation procedures[J]. Evolution, 1967, 21(3): 550-570.

[32] 施立明. 遗传多样性及其保存[J]. 生物科学信息, 1990, 2(4): 158-164. Shi Liming. Genetic diversity and its conservation[J]. Bioscience Communication, 1990, 2(4): 158-164.

[33] 李纯厚, 贾晓平. 中国海洋生物多样性保护研究进展与几个热点问题[J]. 南方水产科学, 2005, 1(1): 66-70. Li Chunhou, Jia Xiaoping. Advances and hot topics for the marine biodiversity protection in China[J]. South China Fisheries Science, 2005, 1(1): 66-70.

[34] Gonzalez E B, Aritaki M, Sakurai S, et al. Inference of potential genetic risks associated with large-scale releases of red sea bream in Kanagawa prefecture, Japan based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis[J]. Marine Biotechnology, 2013, 15(2): 206-220.

[35] Romo M M O V, Suzuki S, Ikeda M, et al. Monitoring of the genetic variability of the hatchery and recaptured fish in the stock enhancement program of the rare species barfin flounder[J]. Fisheries Science, 2005, 71(5): 1120-1130.

[36] Kitada S, Shishidou H, Sugaya T, et al. Genetic effects of long-term stock enhancement programs[J]. Aquaculture, 2009, 290(1-2): 69-79.

[37] Borrell Y J, Alvarez J, Blanco G, et al. A parentage study using microsatellite loci in a pilot project for aquaculture of the European anchovyL[J]. Aquaculture, 2011, 310(3-4): 305-311.

[38] Sawayama E, Takagi M. Genetic diversity and structure of domesticated strains of red sea bream,, inferred from microsatellite DNA markers[J]. Aquaculture Research, 2016, 47(2): 379-389.

[39] Sawayama E, Nakao H, Kobayashi W, et al. Identification and quantification of farmed red sea bream escapees from a large aquaculture area in Japan using microsatellite DNA markers[J]. Aquatic Living Resources, 2019, 32: 1-9.

[40] Gonzalez E B, Nagasawa K, Umino T. Stock enhancement program for black sea bream () in Hiroshima Bay: monitoring the genetic effects[J]. Aquaculture, 2008, 276(1-4): 36-43.

[41] 季晓芬, 段辛斌, 刘绍平, 等.基于微卫星评估草鱼放流亲本对野生群体遗传多样性的影响[J]. 水产学报, 2018, 42(1): 10-17.Ji Xiaofen, Duan Xinbin, Liu Shaoping, et al. Genetic effect of released brood grass carp () on wild population in the Yangtze River inferred from microsatellite markers[J]. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2018, 42(1): 10-17.

[42] 胡新艳, 刘雄军, 周幼杨, 等.基于微卫星的胭脂鱼养殖群体遗传多样性及人工放流监测的分析[J]. 淡水渔业, 2017, 47(1): 35-41.Hu Xinyan, Liu Xiongjun, Zhou Youyang, et al. Genetic diversity ofcultured population based on microsatellite molecular marker and analysis of the artificial release monitoring[J]. Freshwater Fisheries, 2017, 47(1): 35-41.

[43] Wright S. Evolution and the Genetics of Populations[M]. Chicago University: Chicago Press, 1978.

[44] Gonzalez E B, Aritaki M, Knutsen H, et al. Effects of large-scale releases on the genetic structure of red sea bream (, Temminck et Schlegel) populations in Japan[J]. PloS one, 2015, 10(5): e0125743.

[45] Gonzalez E B, Aritaki M, Taniguchi N. Microsatellite multiplex panels for population genetic analysis of red sea bream[J]. Fisheries Science, 2012, 78(3): 603-611.

[46] Takagi M, Taniguchi N, Cook D, et al. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci from Red Sea breamand detection in closely related species[J]. Fisheries Science, 1997, 63(2): 199-204.

Comparison and analysis of genetic variation between the released population and the population in the breeding area ofbased on microsatellite markers

ZHAO Yu1, 2, SUN Dian-rong2, SHAN Bin-bin2, LIU Yan2, YANG Chang-ping2, ZHOU Wen-li1

(1.College of Fisheries, Tianjin Agricultural University, Tianjin 300384, China; 2. Key Lab of South China Sea Fishery Resources Exploitation & Utilization, Ministry of Agriculture; South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, China Academy of Fishery Sciences, Guangzhou 510300, China)

is an important economic species in China’os coastal waters andstock enhancement is atool commonly used to restore the fish stocks. Putting large numbers of hatchery-raised fish into natural habitats can however have some genetic effect on the natural population. Therefore, genetic monitoring should be carried concurrently. In this study, after the release of the stock enhancement in Fangchenggang in 2017, 7 polymorphism microsatellite markers were selected to genotype the genetic differentiation among brood-stock, offspring, and the mixed population. The findings showed that there was no significant difference in allelic richness (13.525 3, 16.428 6) and expected heterozygosity (0.792 7, 0.814 5) between the broodstock and offspring populations, suggesting that there was no loss of genetic diversity in the breeding process.Additionally, the expected heterozygosity (0.814 5, 0.822 8) and allelic richness (16.428 6, 16.755 5) of the offspring and the mixed population after release were similar, suggesting that the two populations had the same genetic diversity.The three populations had a polymorphic information content of 0.7688-0.8055, indicating high genetic variation among the three populations. Moreover, the results of the index of genetic differentiation (0.016 667) and the genetic distance (0.265 375-0.301 915) showed that the genetic differentiation between populations was low and no significant genetic differentiation was established. In summary, after publication, there was hardly any genetic effect of stock enhancement on the mixed population.

; genetic effect; microsatellite markers; stock enhancement

Nov. 18, 2019

S931.5

A

1000-3096(2020)010-0066-08

10.11759/hykx20191118005

2019-11-18;

2020-03-09

中央级公益性科研院所基本科研业务费专项资金资助项目(2020TD01); 中国-东盟海上合作基金资助项目(2016100020); 广东省科技计划项目(2019B121201001)

[Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, No. 2020TD01; China-ASEAN Maritime Cooperation Fund, No. 2016100020; Science and Technology Project of Guangdong Province, No. 2019B121201001]

赵雨(1996-), 女, 硕士研究生, 主要从事渔业资源保护与环境修复研究, E-mail: nzhaoyu@yeah.net; 周文礼,通信作者, 研究员, E-mail: saz0908@126.com

(本文编辑: 谭雪静)