Effects of Constant High Temperature on Survival, Development and Reproduction of Aphis glycines Matsumura

2020-11-03LiuJianBaiBingGaoBoandLiuZhe

Liu Jian, Bai Bing, Gao Bo, and Liu Zhe

College of Agriculture, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin 150030, China

Abstract: Life cycle of Aphis glycines Matsumura is characterized as heteroecious and holocyclic.Temperature is one of the most important abiotic factors that can affect development and reproduction of A.glycines.In this study, A.glycines were fed on G.max at five constant temperatures, 27℃, 29℃, 31℃, 33℃ and 35℃.The development and reproduction of A.glycines were studied in the laboratory and the data were compared to controls on G.max at 25℃.The results showed that most of A.glycines nymphs developed into adults successfully at temperature range from 25℃ to 33℃, but only a few nymphs could develop into adult at 35℃.Longevity,fecundity and body sizes of A.glycines adults all decreased gradually when temperature increased from 25℃ to 33℃.Intrinsic rate of increase of A.glycines at 27℃ was as big as that at 29℃, which were bigger than those at 25℃, 31℃ and 33℃.At 35℃, no offspring were deposited by adults.It provided information on development and reproduction of A.glycines exposed to high temperatures,which was important to study the adaptability of A.glycines to environmental temperature and for predicting its dynamics in soybean field in northeast China.

Key words: Aphis glycines Matsumura, high temperature, development

Introduction

Soybean aphid,Aphis glycinesMatsumura, is a secondary important pest of soybean,Glycine max(L.) Merrill, which is native to Asia (Wuet al., 2004).After 2000,A.glycinesinvaded into North America(Davidet al., 2004) and Oceania (Murray and Petter,2002), and became a worldwide pest.They usually accumulate on top leaves, tender leaves and tender stems of soybeans, and weaken the plants by their sucking behavior (Wanget al., 1994; 1996).Even at a low population density, feeding byA.glycinesand some fungi occurring on honeydew on leaves produced by the aphid both can impair photosynthetic progress in soybeans greatly.In addition,A.glycinescan transmit some species of plant viruses, such as soybean mosaic virus, alfalfa mosaic virus (Hillet al.,2001; Clark and Perry, 2002) and potato virus Y (Daviset al., 2005).During years with heavy infestations ofA.glycines, they can cause serious damage and yield reduction to soybeans (Sunet al., 2000).

Life cycle ofA.glycinesis characterized as heteroecious and holocyclic.When the daily average temperature is above 10℃ in spring, overwintering eggs on primary hosts hatch and become wingless fundatrices.Their offspring undergo several generations, then alate viviparous females are produced which migrate into soybeans.In summer, viviparous females occur in the field.When temperature decreasesand day-length shortens in autumn, winged gynoparae are produced and then they migrate to primary hosts where they produce oviparae.Meanwhile, winged males develop in soybeans also migrate to primary hosts where they mate with oviparae, which lay overwintering eggs (Wanget al., 1962; Wuet al., 2004).

Summer hosts ofA.glycinesare cultivated soybean,G.max, and wild soybean species,Glycine sojaSieb and Zucc (Hillet al., 2004).The winter hosts areRhamnus davuricusPall.(Wanget al., 1962),Rhamnus japonicaMaximowicz (Takahashiet al.,1993),Rhamnus catharticaL.,Rhamnus alnifoliaL' Héritier andRhamnus lanceolataPursh (Voegtlinet al., 2004; Yooet al., 2005).In recent years, Japanese metaplexis,Metaplexis japonica(Thunb.) and white clover,Trifolium repensL., were also reported as hosts ofA.glycines(Chenet al., 2015; Chenet al., 2017).Some field surveys on natural enemies ofA.glycineswere also conducted, especially when they invaded into North America since 2000.In north America,Orius insidiosus(Say) (Butler and O'Neil, 2007) andPropylea quatuordecimpunctataL.(Mignaultet al.,2006) are identified as the dominant natural enemies.In northeast China, 13 species of predators are found,such asPropylaea japonica(Thunberg),Harmonia axyridis(Pallas),Chrysopa sinicaTjeder and it also indicates that predator communities can partially suppress soybean aphid population density in soybean fields (Liuet al., 2012).In early June,A.glycinescan be found in soybean fields.A.glycinesincrease sharply usually from July to August.Soybean aphids disappear in field in September (Fanet al., 2017; Daiet al., 2014).To effectively manipulateA.glycinespopulation and achieve an optimal benefit/cost ratio for management, a clear knowledge of the economic and control thresholds is necessary.The average economic threshold to apply insecticides is reported as 250 soybean aphids per plant (McCarvilleet al.,2011).Control ofA.glycinesinvolves several distinct tactics, including chemical control (Biet al.,2016), cultural control (Hanet al., 2016), biological control (Koch and Costamagna, 2017) and host plant resistance (Wengeret al., 2014).These control options can be used individually or together.

Temperature is one of the most important abiotic factors that can affect development and reproduction of herbivorous insects.Survival rate ofAphis gossypiiGlover nymph is 90% at 25℃, and it is only 36.7% at 30℃.With the temperature increasing from 10℃ to 25℃, the intrinsic rate of increase, net productive rate and finite rate of increase ofA.gossypiiall increase gradually (Xuet al., 2019).Aphis citricolaVan der Goot develops and reproduces well at 20℃.When the temperatures are above or below 20℃, intrinsic rate of increase, net productive rate and finite rate of increase of this pest all decrease (Xuet al., 2019).At 22℃, adult fecundity, adult lifespan and net productive rate ofSitobion avenae(Fabricius) are the biggest, while their intrinsic rates of increase are smaller (Xu, 2015).The optimum temperature forA.gycinesdevelopment is 25℃.At this temperature,population number ofA.glycinescan be doubled in 1.5 days (McCornacket al., 2004) and the average adult fecundity is 27.60 offspring per female (Xuet al., 2011).Extreme temperatures affect development ofA.gycinessignificantly.At 30℃ and 10℃, the average adult fecundity ofA.gycinesare both only about 15 offspring per female (Xuet al., 2011).With temperatures increasing which are all above 25℃, the data on mean generation time, net productive rate, life expectancy (McCornacket al., 2004) and adult body size (Chenet al., 2015) ofA.gycinesall decrease gradually.In Harbin Region, northeast China, the environmental average temperatures are keeping rising in recent years, with the temperature-rising rate 0.37℃per 10 years (Yuet al., 2009; Zhouet al., 2013).In summer in this region, the daily average temperature is often above 27℃ (2007-2014, Heilongjiang Meteorological Bureau, China).WhenA.glycinesare exposed to the higher temperatures in the field, their survival,development and reproduction are still in questions.

In this study,A.glycineswere fed onG.maxat 27℃, 29℃, 31℃, 33℃ and 35℃.Their survival,development and reproduction were studied in thelaboratory and the data were compared to the controls onG.maxat 25℃.The results provided information on development and reproduction ofA.glycinesexposed to high temperatures above 27℃, which was important to study the adaptability ofA.glycinesto environmental temperature and for predicting its dynamics in soybean field in northeast China.

Materials and Methods

Aphid source and host plants

Soybean aphids,A.glycines, were collected from a soybean field in Northeast Agricultural University(NEAU), Harbin, Heilongjiang Province, China (45°7'N, 126°6'E) in 2018.The colony was maintained on soybean seedlings (variety Heinong 51) in a growth chamber at (25±1)℃, 70%±5% relative humidity and a photoperiod of 14 : 10 (L : D) h with artificial light of 12 000 LX.

Seeds ofG.max(variety Heinong 51) were purchased from Fangyuan Agriculture Corporation, Wuchang,Heilongjiang Province, China.Soybeans were grown in a growth chamber with 6 to 10 seeds per pot in 10 cm×10 cm (diameter×height) plastic pots at (25±1)℃, 70%±5% RH and a photoperiod of 14 : 10 (L : D) h.Seedlings 15-20 cm tall at the V2 growth stage (Fehret al., 1971) were used for experiments.

Survival, development and reproduction of A.glycines at different temperatures

Apterous adults ofA.glycineswere removed from the monoclonal population onto four pots ofG.maxplants (one aphid per pot).The plants were placed in a growth chamber at (25±1)℃, 70%±5% RH and a 14 : 10 (L : D) h photoperiod for a 2-week reproductive period.Then, 50 apterous adults were transferred from these four pots of soybeans onto another five pots of soybeans (10 adults per pot).These plants were placed in a growth chamber at the same conditions mentioned above for a 24-hour reproductive period, after which,all the adults were removed.With a small brush, newly deposited nymphs were individually removed from the plants for the experiment.

A piece of square moisturizing cotton, two by 2 cm (length by width), was put at the bottom of a 45 mL, four by 4.5 cm (diameter by height) glass beaker, and a piece of round filter paper of 4 cm in diameter was put on the surface of the moisturizing cotton.Then, the filter paper was wetted with 2 200 μL water by dropping onto the surface of filter paper using a pipette.Detached leaves ofG.maxwere cut into 1.5 cm2square pieces using a pair of scissors.A nymph ofA.glycineswas removed with a small brush from the colony mentioned above onto the reverse side of a square leaf piece adhered to the surface of the filter.The beaker was then placed upside down onto a 5-cm-diameter plastic Petri dish (moisturizing cotton method).For each temperature treatment, 50 nymphs were tested.Beakers were placed in growth chambers at 25℃, 27℃, 29℃,31℃, 33℃ and (35±1)℃, 70%±5% RH and a 14 : 10(L : D) h photoperiod.Individual nymphs were checked daily for ecdysis and survival.Adults that had been reared from nymphs at 25℃ to (35±1)℃ were maintained in the same conditions as the immature insects.Nymphs deposited by each female were counted and removed daily.Adult longevity was recorded daily until the death of each adult.Leaves and media were replaced every 5-7 days, when leaves became yellowish or upon observation of fungal growth (Chenet al., 2017).

Body sizes of A.glycines adult at different temperatures

When the adults were dead in trial on survival, development and reproduction ofA.glycinesmentioned above, they were kept in 75% alcohol solution.Then,body length and body width of adults were measured by optical microscope and a micrometer.To estimate the body size ofA.glycinesadult, superficial area parameter (SA), which was counted asSA=π×a×b/4(π≈3.14,awas the body length value,bwas the body width value), was used to calculate and evaluate the body sizes of adults (Chenet al., 2015).

Data analysis

Raw data of nymph duration, adult longevity and adult fecundity, along with their means and standard errors ofA.glycinesat different temperatures were calculated by TWOSEX-MSChart software (Chi and Liu, 1985;Chi, 2017).Differences in nymph duration, adult longevity, adult fecundity and adult body size ofA.glycinesamong different temperatures were analyzed by analysis of variance (PROC GLM) and Tukey's honest significant difference (HSD) tests (SAS 8.1).

Means and standard errors of intrinsic rate of increase (r), net productive rate (R0), finite rate of increase (λ) and mean generation time (T) were calculated using bootstrap technique (Efron and Tibshirani,1993) in the computer program TWOSEX-MSChart(Chi, 2017).Because bootstrap analysis used random resampling, a small number of replications would generate variable means and SEs.200 000 bootstrap iterations were used to reduce the variability of the results.Differences in these four parameters ofA.glycinesamong different temperatures were analyzed by a paired bootstrap test (Huang and Chi,2011; Yuet al., 2013).

Results

Survival of A.glycines at different temperatures

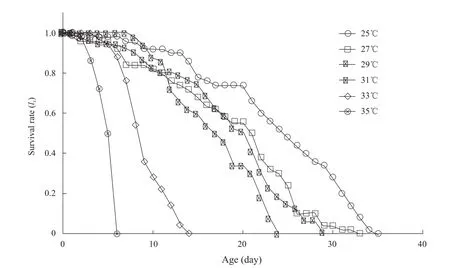

Survival time ofA.glycinesdecreased gradually, when temperatures increased from 25℃ to 35℃ (Fig.1).At temperature ranges from 25℃ to 31℃, almost all the nymphs ofA.glycinesdeveloped into adults successfully (Table 1), and they survived well under the same trend (Fig.1).At 33℃, most of nymphs could develop into adults, but they were all dead within 14 days.At 35℃, only few nymphs could develop into adults and they were dead within 6 days (Table 1 and Fig.1).

Fig.1 Age-specific survival rate (lx) of A.glycines at different temperatures

Nymph duration, adult longevity and adult fecundity of A.glycines at different temperatures

Nymph duration ofA.glycinesat 25℃ was as long as that at 33℃, which were both longer than that at 27℃,29℃ and 31℃ (df=5, 227,F=27.08,P<0.0001).At 35℃, only two nymphs ofA.glycinescould develop into adults and the nymph duration was 4.00 days(Table 1).

Table 1 Nymph duration, adult longevity and adult fecundity (Mean±SE) of A.glycines at different temperatures

Adult longevity ofA.glycinesdecreased gradually,when temperatures increased from 25℃ to 35℃.Adult longevity ofA.glycinesat 25℃ was as long as that at 27℃ and 29℃ and it was longer than that at 31℃.Adult longevity ofA.glycinesat 33℃ and 35℃was both the shortest, which were 4.11±0.39 and 1.00 days (df=5, 227,F=26.66,P<0.0001) (Table 1).

Adult fecundity ofA.glycinesdecreased gradually,when temperatures increased from 25℃ to 35℃ (df=5, 227,F=106.20,P<0.0001).At 25℃, the fecundity ofA.glycinesadult was the biggest, with 53.22±2.50 offspring.At 35℃, no offspring were deposited though two nymphs developed into adults (Table 1).

Life table parameters of A.glycines at different temperatures

When the temperature increased from 25℃ to 29℃,intrinsic rate of increase and finite rate of increase ofA.glycinesboth increased.And then they decreased gradually when temperatures increased from 31℃to 33℃.Net productive rate ofA.glycinesat 25℃was as big as that at 27℃, which were both bigger than that at 29℃, 31℃ and 33℃.Mean generation time ofA.glycinesdecreased gradually, when temperatures increased from 25℃ to 33℃.At 35℃,the value of intrinsic rate of increase, net productive rate and finite rate of increase ofA.glycineswere zero day-1, one offspring and one day-1, respectively(Table 2).

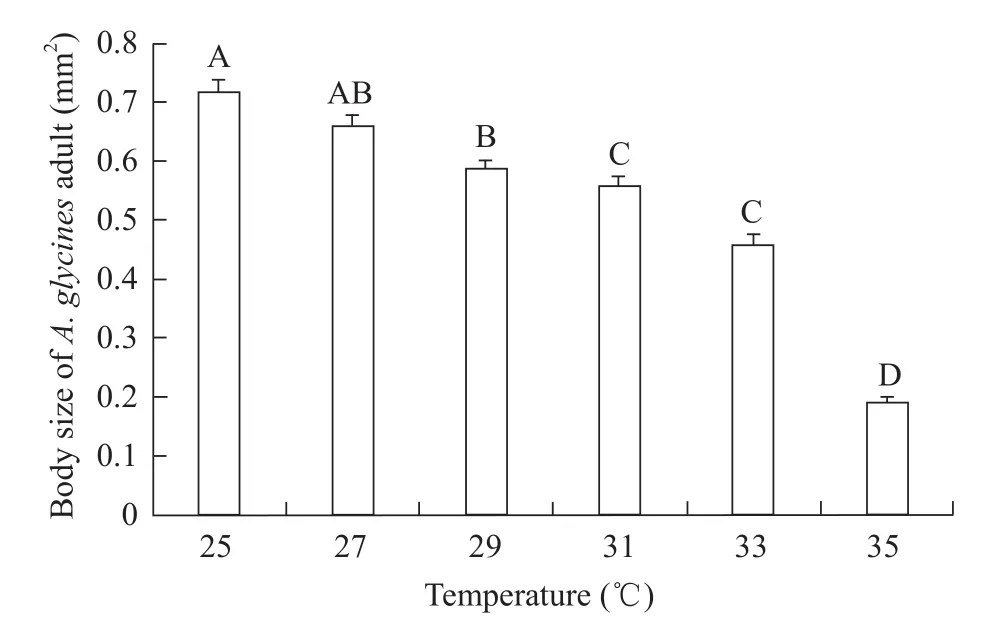

Body sizes of A.glycines adults at different temperatures

When the temperature increased from 25℃ to 35℃,body sizes ofA.glycinesadults decreased gradually(df=5, 205,F=119.43,p<0.0001).At 25℃, the body size of adult was the biggest, with data of (0.72±0.02) mm2.At 35℃, the body size of adult was (0.19±0.01) mm2that was the smallest.

Table 2 Life table parameters (Mean±SE) of A.glycines at different temperatures

Fig.2 Body sizes of A.glycines adults at different temperatures

Discussion

In this study, it showed that most ofA.glycinesnymphs could develop into adults and offspring could be deposited successfully at the temperature range to 25℃-33℃, which was consistent with the reported results (Hiranoet al., 1996; Chenet al.,2015).At 35℃, four percentage ofA.glycinesnymphs developed into adults, which was different from the reported results thatA.glycinesnymphs could not complete development at this temperature (Wanget al., 2019; Mccornacket al., 2004).

At 25℃, the values ofA.glycinesnymph duration,adult longevity and adult fecundity were all bigger than those ofA.glycinesreared by leaf-disc method(Wanget al., 2019).The differences could probably be attributed to different rearing methods used in each study.In this study,A.glycineswere reared by moisturizing cotton method where more water was kept in the moisturizing cotton under the filter paper in beakers.Thus, the square pieces of soybean would survive better than that in leaf-disc method for being able to get enough water.SoA.glycinesdeveloped and reproduced better in this study than those reared by leaf-disc method (Wanget al., 2019).At 27℃, the values ofA.glycinesnymph duration, adult longevity and adult fecundity were all bigger than those reported data ofA.glycinesreared by living soybean plants (Hiranoet al., 1996).Whether it showed thatA.glycinescould develop and reproduce better on detached leaves used in moisturizing cotton method than that on living plants, it was still in questions.

In this study, intrinsic rate of increase ofA.glycinesat 25℃ was smaller than that of aphids reared by leafdisc method, but the adult longevity ofA.glycineswas longer than the reported results (Wanget al.,2019).It was probably an important adaptive strategy ofA.glycinesto environment.As mentioned above,when adult longevity ofA.glycineswas shorten, they presented a big intrinsic rate of increase to increase their population number.In this study, the intrinsic rates of increase ofA.glycinesat 25℃ and 27℃ were both smaller than the reported 0.474 day-1(Mccornacket al., 2004) and 0.533 day-1(Hiranoet al., 1996).Soybean aphids used in this study were collected in Harbin, northeast China, which were different from the aphid populations collected in Morioka, Japan (Hiranoet al., 1996) and in Rosemount, America (Mccornacket al., 2004).WhenA.glycineswere collected from these different regions, intrinsic rates of increase ofA.glycinesfrom these different geographic populations were probably different from each other, even when they were reared at the same temperature.

Body size ofA.glycinesadult decreased gradually,when the temperature increased from 25℃ to 35℃,which was consistent with the reported results (Chenet al., 2015).Body size ofA.glycinesadult was 0.72 mm2at 25℃, which was slightly smaller than 0.76 mm2reported by Yanget al(2010).ThoughA.glycinesused in these aforementioned studies were both collected in soybean fields in NEAU, they were taken in different years and from different sites.There were four biotypesA.glycinesin America,which differed in survival, develop and reproduction when they were fed on soybeans with differentRag(resistance toAphis glycines) genes (Hillet al., 2006).Whether there were different biotypes ofA.glycinesin northeast China, it was still in questions up to now.IfA.glycinesused in these studies mentioned above were from different biotypes, the question, why the bodysize ofA.glycinesin this study was smaller than the reported results (Yanget al., 2010), would probably be answered.

Body size ofA.glycinesadult was the smallest at 35℃, which was consistent with the reported result of cotton aphid,A.gossypii, with smaller body sizes at high temperatures (Liuet al., 2003).At high temperatures, herbivores usually had to increase physiological metabolism which would use up a large number of biological energy in body (Duet al., 2007).The more biological energy was used to increase physiological metabolism, the fewer biological energy could be used to construct body sizes.This was probably one of the reasons whyA.glycinespresented the smallest body size at 35℃.

Soybean aphids thrived at the temperature range of 25℃-33℃ in the laboratory.So it was believed thatA.glycinescould survive well in field, when the environmental temperature was below 33℃.Instead of constant temperatures, aphids were subjected to fluctuating temperatures in nature.In northeast China, environmental temperatures usually fluctuate significantly between day and night in summer, even with above 35℃ in the day and below 25℃ at night (2007-2014, Heilongjiang Meteorological Bureau, China).If these studies could be conducted at fluctuating temperatures between day and night, more accurate results on development and reproduction ofA.glycinesat these temperatures would probably be acquired.Though only two nymphs ofA.glycinesdeveloped into adults at constant 35℃, a number ofA.glycinesnymphs could probably survive and develop into adults successfully at fluctuating 35℃ in nature.

In this study, individual aphids were checked daily for survival, ecdysis and the deposited nymphs.If they could be checked every 12 h in trials, duration of nymph and adult would be recorded more accurately.Though the temperatures above 27℃ often occurred in northeast China, it was often short-term in nature (2007-2014, Heilongjiang Meteorological Bureau, China).If studies on effect of short-term high temperatures on survival, development and reproduction ofA.glycinesare conducted in the future,whether they can complete development at 35℃ in nature will probably be answered in detailed.

Conclusions

Most ofA.glycinesnymphs developed into adults successfully at temperature range from 25℃ to 33℃, but only a few nymphs could develop into adult at 35℃.Longevity, fecundity and body sizes ofA.glycinesadults all decreased gradually when temperature increased from 25℃ to 33℃.The results were important to study the adaptability ofA.glycinesto environmental temperatures.

杂志排行

Journal of Northeast Agricultural University(English Edition)的其它文章

- Effects of Drought Stress and Re-watering on Osmotic Adjustment Ability and Yield of Soybean

- Winter Hardiness Physiological Response with Dehydration in Winter Wheat

- Fine Genetic Mapping of Dwarf Trait in Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.)Using a RIL Population

- Evolution of Heavy Metal Speciation During a Large-scale Sewage Sludge Composting

- Generation of a Canine-origin Neutralizing scFv Against Canine Parvovirus

- Study on Relationship Between Differential Proteins of Bacillus cereus LBR-4 and Its Salt Tolerance Mechanism