Daily high-dose aspirin does not lower APRI in the Aspirin-Myocardial Infarction Study

2020-05-25ShilpaTiwariHecklerGordonJiangYuryPopovKennethMukamal

Shilpa Tiwari-Heckler, Z. Gordon Jiang,✉, Yury Popov, Kenneth J. Mukamal

1Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, 2Division of General Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Abstract

Keywords: liver fibrosis, aspirin, APRI, antiplatelet, AMIS

Introduction

Liver fibrosis is a common pathway for most forms of chronic liver disease that leads to cirrhosis and liver failure. In addition to its well-established function in thrombus formation, platelets play a crucial role in the regulation of inflammation and tissue repair[1]. In the liver, platelet-derived growth factor-beta (PDGF-β) is a key profibrogenic cytokine that promotes the activation of quiescent stellate cells into myofibroblasts[2–3]. In addition, activated platelets release tumor growth factor-beta and chemokine (CX-C motif) ligand 4. Together with PDGF-β, these cytokines can promote fibrogenesis in liver diseases through the activation of quiescent hepatic stellate cells[4–5]. As a result, antiplatelet therapy, antibody-mediated platelet depletion, and aspirin protect against liver fibrosis in murine models of liver fibrosis[4].Similarly, aspirin, ticlopidine, and cilostazol, three antiplatelet agents, attenuate liver steatosis,inflammation and fibrosis in diet-induced rat models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)[6]. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a nationally representative crosssectional study, suggested that individuals using aspirin, especially those with chronic liver diseases,had lower indices of liver fibrosis compared to those with no aspirin use[7]. This putative anti-fibrotic association was not seen in those with the use of ibuprofen[7]. A recent study by Schwarzkopfet aldemonstrated an inverse association between the use of antiplatelet agents (aspirin and/or clopidogrel) and liver fibrosis measured by transient elastography among patients with cardiovascular diseases[8]. In their study, the circulating level of PDGF-β was associated with platelet counts but not with the use of antiplatelet agents. Furthermore, a prospective study by Simon and colleagues showed that among individuals with NAFLD and low-grade fibrosis (stage 0–2), the daily use of aspirin is associated with a significantly lower risk of incidental development of advanced liver fibrosis (stage 3–4) measured by noninvasive fibrosis indices[9]. The putative anti-fibrotic effect of antiplatelet agents, such as aspirin, has not yet been studied in clinical trials. Here, we examine the prospective impact of daily aspirin use on liver fibrosis measured by the aspartate aminotransferase(AST)-to-Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) in the Aspirin-Myocardial Infarction Study (AMIS).

Materials and methods

AMIS was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind,placebo-controlled trial, sponsored by National Heart,Lung and Blood Institute and conducted to study the impact of aspirin on mortality among individuals with a documented history of myocardial infarction[10]. A total of 4 524 men and women aged between 30 and 68 in the United States were randomized to receive either one gram of aspirin or placebo daily for three years. Platelet count and AST were measured at baseline and annually at follow-up visits. Primary data were provided by NHLBI. APRI, a validated fibrosis index, was measured as previously described[11]. We analyzed the association between aspirin use and changes in APRI over time using generalized estimating equations and an unstructured correlation matrix, in which the impact of aspirin was calculated as the time-by-treatment interaction between the year of follow-up (0 –3) and aspirin assignment. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the impact of aspirin on subjects likely to have significant liver fibrosis defined by APRI≥0.7 at baseline. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 13 (College Station, USA).

Results

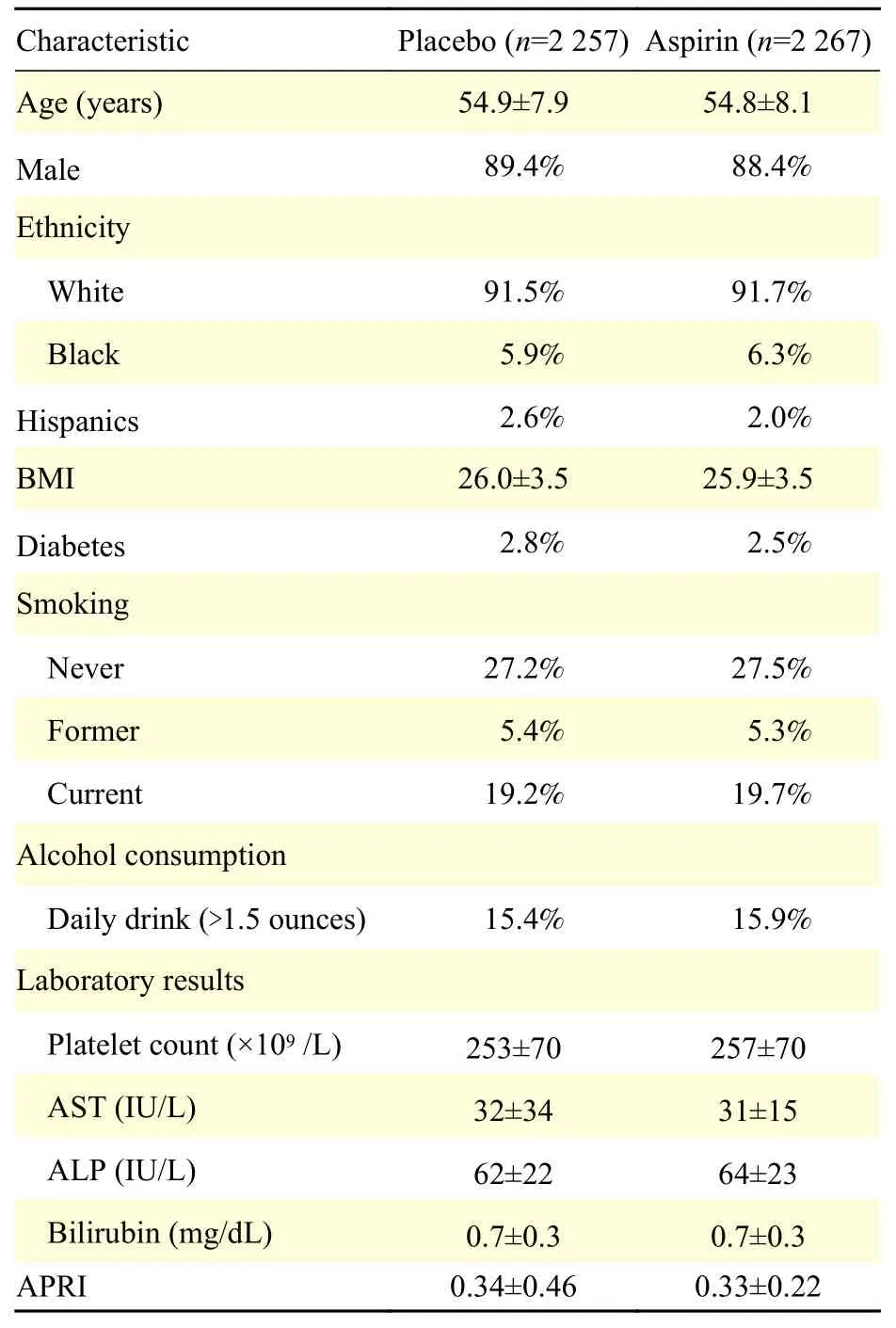

The baseline characteristics of patients in the AMIS trial are summarized inTable 1. Most study participants were Caucasian (92%) and male (~89%)with a mean age of 55 years, body-mass index of 26,and a prevalence of diabetes of 2.6%. The mean APRI values at baseline were 0.34±0.46 in the placebo and 0.33±0.22 in the aspirin groups. Only 2.5% of individuals (n=113) had baseline APRI higher than 0.7.

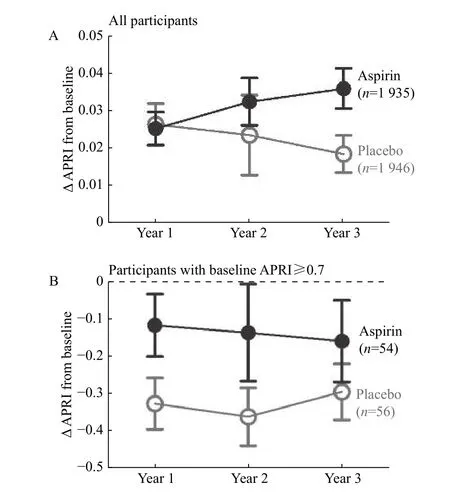

Over three years, mean APRI increased in both aspirin and placebo groups compared to baseline.Assignment to aspirin tended to be associated with a greater increase in the rate of change in APRI over time than placebo (difference in the rate of change 0.007 per year; 95% CI 0.002–0.015,P=0.12) (Fig. 1A).There was no significant difference in the rate ofchanges in platelet counts between the aspirin and placebo groups over time (P=0.4), but a trend toward 0.52 IU/L higher AST annually in the aspirin group compared to the placebo group (95% CI 0.05–1.09,P=0.07) was noted. Among individuals with elevated APRI at baseline (mean APRI of 1.1±0.5 for the aspirin and 1.0±0.4 for the placebo group), APRI values tended to decrease more consistently over time among subjects who received aspirin than among those who received placebo (Fig. 1B), but the differences in changes of APRI over time were not significant between the two groups (P=0.7).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of study participants

Discussion

Current strategies of treating fibrosis in chronic liver diseases anchor on the treatment of underlying causes to prevent disease progression. There is an urgent need for therapeutic interventions that can specifically target fibrogenesis and potentially reverse fibrosis. Accumulating evidence suggests that antiplatelet agents, such as aspirin, may have antifibrotic properties and could be a cost-effective therapeutic option.

Fig. 1 Changes in APRI over time in AMIS. A: Changes in APRI compared to baseline among all subjects in aspirin and placebo groups. B: Changes in APRI compared to baseline among subjects with probable significant fibrosis (APRI≥0.7). Three participants with an elevated AST more than 200 IU/L at baseline but normal at follow-ups were excluded due to concerns for acute hepatitis. The error bar represents standard deviation.

Randomized clinical trials testing this therapeutic indication of aspirin are yet to be conducted. Very few are antiplatelet clinical trials with liver-related measurements. AMIS allowed us to leverage the annual measurement of the platelet count and AST to calculate APRI, a validated index of liver fibrosis. In this study, daily use of 1 000 mg of aspirin did not change the three-year trajectory of APRI compared with the placebo. Although APRI is an imperfect index for liver fibrosis, these results from a large randomized trial suggest an absence of sizable benefit from daily aspirin in the primary prophylaxis for liver fibrosis among individuals without pre-existing liver diseases. On the contrary, there was a trend toward higher APRI among aspirin users over time, albeit small and unlikely to be clinically significant. AMIS used 1 000 mg of aspirin in the treatment arm, a practice common at the time of the clinical trial, but significantly higher than current standards. As the inhibition of aspirin on platelets is irreversible, a higher dose is not likely to render additional benefits but could result in significant side effects. Of note,idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity due to aspirin can occur,especially at the high dose used in AMIS. Therefore, a liver protective effect of aspirin could manifest at lower doses of aspirin at 75–100 mg as used for cardiovascular prevention. The dose-effectiveness of aspirin for liver fibrosis has not been formally studied.

The AMIS trial does not directly address the impact of aspirin among individuals with chronic liver disease, as few participants had significant preexisting fibrosis by APRI. The negative result does not negate the preclinical observations of platelet involvement in the regulation of liver inflammation and fibrosis. In one retrospective study, low-dose daily aspirin was associated with a lower risk of liver fibrosis progression among patients with HCV recurrence after liver transplantation[12]. Others have noted that an association between aspirin use and reduced risks of hepatocellular carcinoma in a mouse model of chronic hepatitis and human studies[13]. In AMIS, there was a numerical tendency toward lower APRI values over time with aspirin use in the subgroup of subjects with high APRI values, but this result was far from significant and limited by regression to the mean among those with initially high APRI values.

As a secondary analysis, this study has major limitations that include a patient population not representative of patients with chronic liver diseases,an imperfect proxy fibrosis measurement, a dose of aspirin higher than the current standard and therefore unable to minimize its adverse effects, and a moderate duration of follow-up. A negative result here highlights the need forde novoclinical trials to investigate the potential benefit of antiplatelet agents for chronic liver diseases. Nonetheless, observations here can provide useful insights for future trial design.Foremost, the putative antifibrotic benefit of antiplatelets such as aspirin is likely minimal among individuals without chronic liver diseases. This was also seen in NHANES Ⅲ where the negative association between aspirin use and fibrosis indices was significantly larger among individuals with chronic liver diseases than in those with no liver diseases[7]. Hence, a primary prophylaxis trial, such as the design in the Physician Health Study, may not be appropriate. The modality of fibrosis measurement and the duration of follow-up are also important considerations that need to be weighed against the costs of the study.

Overall, we report a negative association between the daily use of high-dose aspirin and changes in APRI over three years among patients with a prior history of myocardial infarction. Despite encouraging preclinical and cross-sectional studies, randomized clinical trials are necessary to evaluate the potential therapeutic value of antiplatelet agents in treating liver fibrosis in chronic liver diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work is in part supported by a German Research Foundation grant to STH (DFG TI 988/1-1),an NIH grant to ZGJ (K08DK115883) a Clinical Research Award from ACG and an Alan Hoffman Clinical and Translational Research Award from AASLD to ZGJ.

杂志排行

THE JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH的其它文章

- Angiosarcomatous component in gliosarcoma: case report and consideration of diagnostic challenge and hemorrhagic propensity

- RNA-seq analysis identified hormone-related genes associated with prognosis of triple negative breast cancer

- The level of bile salt-stimulated lipase in the milk of Chinese women and its association with maternal BMI

- AAV-mediated human CNGB3 restores cone function in an allcone mouse model of CNGB3 achromatopsia

- Inhibitory role of peroxiredoxin 2 in LRRK2 kinase activity induced cellular pathogenesis

- H2S protects against diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis by preventing the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome