Rare giant asymptomatic skull metastasis from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

2020-05-10MnToChenYongQingZhouTinWuDeXinChengGuLiRenZhn

Mn-To Chen , Yong-Qing Zhou , Tin-Y Wu , De-Xin Cheng , Gu Li , Ren-Y Zhn , *

a Department of Neurosurgery, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310003, China

b Department of Neurosurgery, Zhuji People’s Hospital of Zhejiang Province, Zhuji 311800, China

TotheEditor:

Skull metastases are common cranial tumors in adults. Breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer and malignant lymphoma are the most common types of primary tumor. Skull metastases are often asymptomatic; however, they can also cause local pain and cranial nerve palsies, and even severe disability due to compression of the dural sinuses [1] . In these cases, surgery is necessary to improve the patients’ quality of life, especially relieving the mass effect of skull metastasis. Skull metastases from less common malignant tumors such as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) have rarely been described [2-6] , and its treatment still remained a big challenge for all neurosurgeons. Here, we present an asymptomatic case of giant skull metastases from ICC treated with complete resection and chemotherapy.

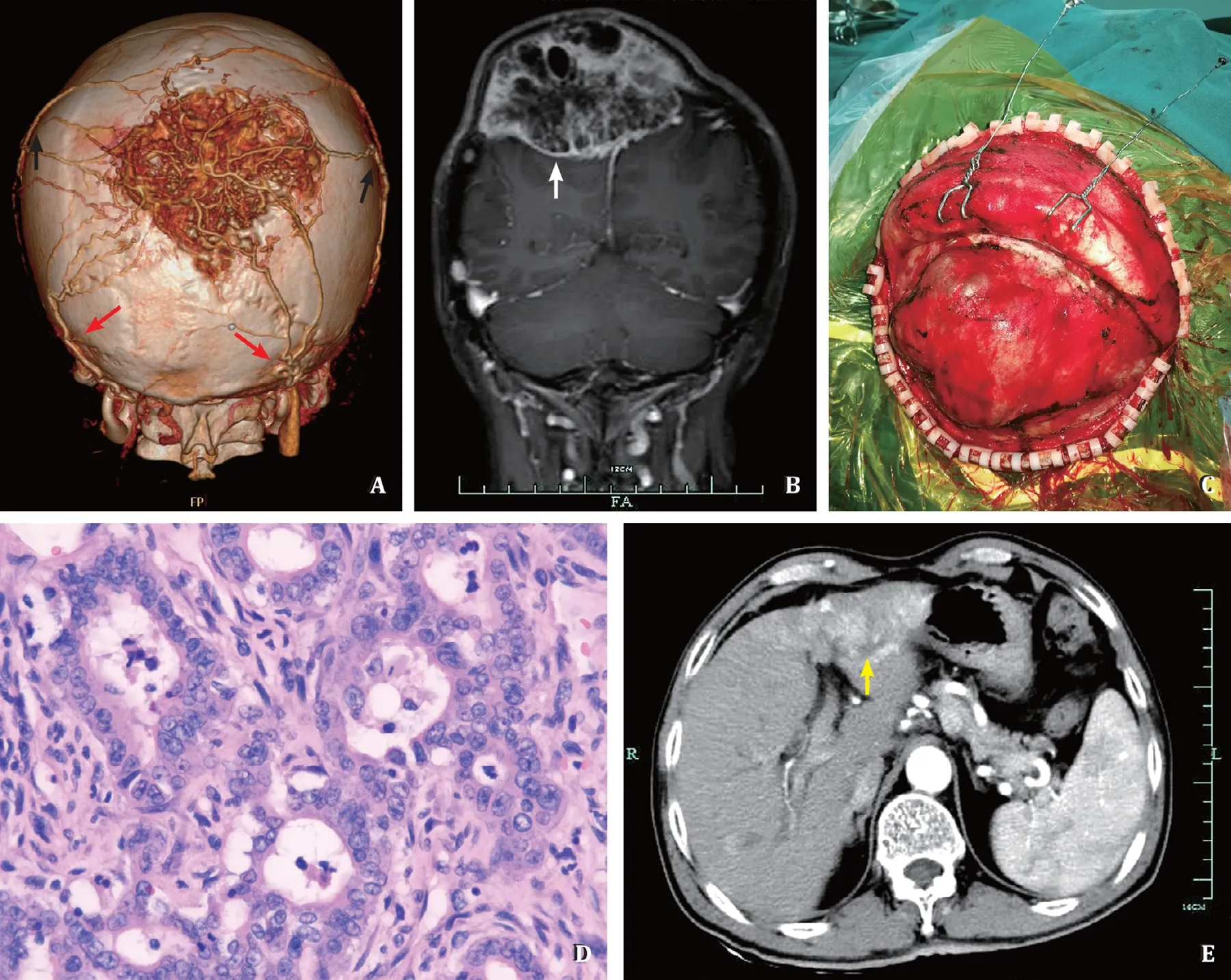

A 66-year-old male came to our hospital with a complaint of a painless mass in the bilateral parietal-occipital region of the head. The patient had discovered this mass nearly 1 year ago,and it had grown rapidly in recent months. He had no serious diseases, except for laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to gallstones 1 year ago. A cranial computed tomography (CT) angiography scan showed a giant mass with rich blood supply from the bilateral occipital arteries and superficial temporal arteries ( Fig. 1 A).Magnetic resonance imaging indicated an 8 × 6 × 6 cm mass in the bilateral parietal-occipital skull, and the adjacent brain parenchyma and sagittal sinus were oppressed noticeably ( Fig. 1 B).The preoperative laboratory data showed that HBsAg was positive without liver dysfunction. Hematology was normal.

A craniectomy was rapidly conducted. The tumor was completely resected. The giant mass penetrated the skull and invaded the dura ( Fig. 1 C). Frozen sections indicated an adenocarcinoma metastasis. Histopathological examination showed adenocarcinomatous cells with tube arrangement ( Fig. 1 D) and focal bone invasion. Immunohistochemical results was positive for cytokeratin 7 (CK7) and CK19, while negative for CK20, caudal-related homeobox 2 (CDX2), prostate-specific antigen (PSA), thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), napsin A and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP-15). The contrast-enhanced CT indicated abnormal enhancement in the left lobe ( Fig. 1 E) and likely to be ICC and retroperitoneal lymphadenectasis. Besides, the postoperative tumor marker carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) was 153.7 U/mL. With the combination of histopathological examination, immunohistochemical findings contrast-enhanced CT, and laboratory data CA19-9, the diagnosis of skull metastasis from ICC was confirmed in the clinical settings.

The postoperative recovery was satisfactory with no neurological deficits. Then, the patient further received four phases of chemotherapy with gemcitabine (1500 mg) and cisplatinum(35 mg). Unfortunately, the patient suffered myelosuppression and died 6 months after surgery.

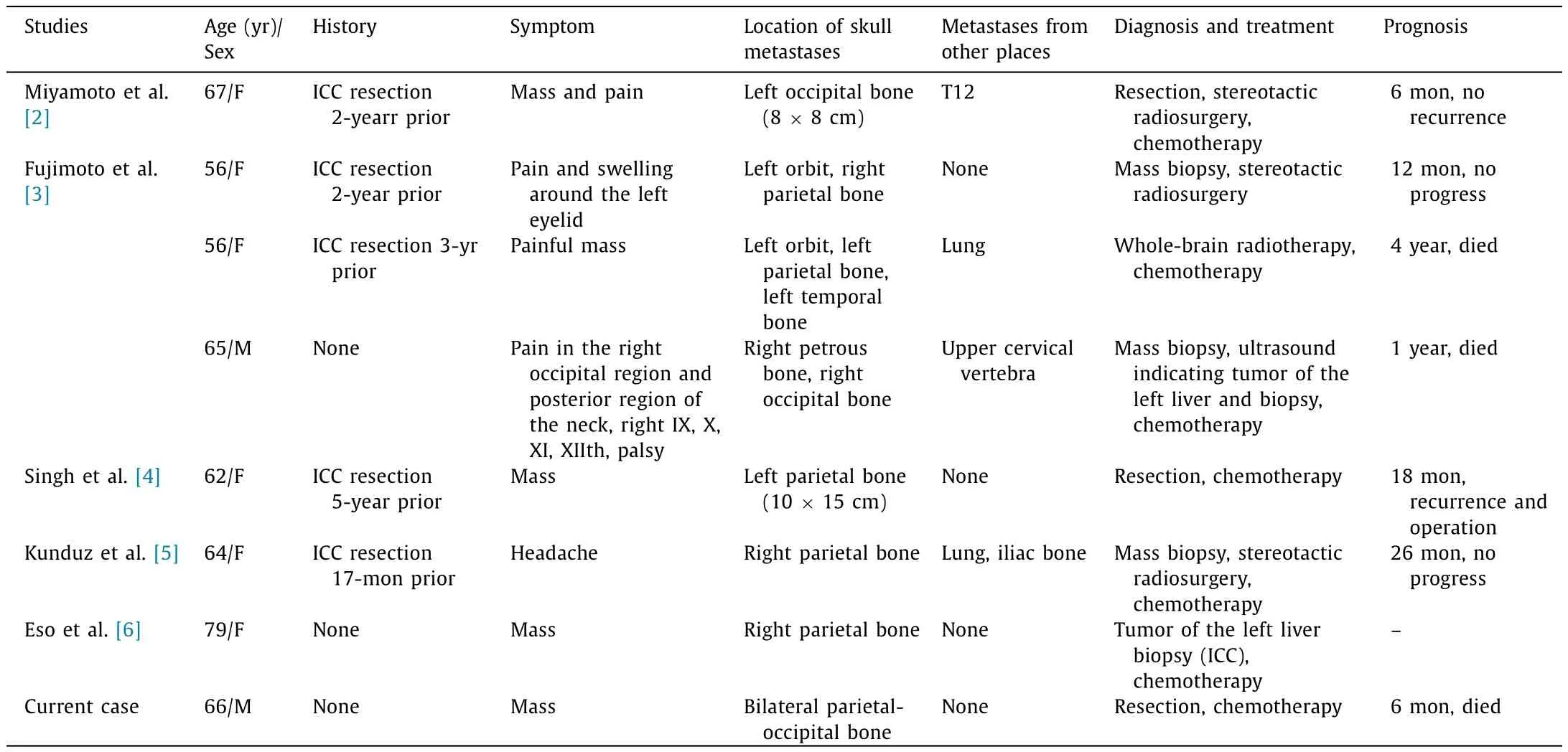

After a thorough search of the literature, we found five studies that included 7 cases of skull metastases from ICC ( Table 1 ).Hematogenous pathway and osseous pathway are the main principle ways for skull metastases. The hematogenous pathway goes from the lung to the skull, which was the case in patient 2 in the study by Fujimoto et al. [3] and in the patient in the study by Kunduz et al. [5] . The osseous pathway occurs via the cerebrospinal venous system and includes two main divisions: one division includes the cortical veins, dural sinuses and cavernous sinus, while the other includes the vertebral venous system. We believe that our case, along with the patient in the study by Miyamoto et al. [2]and patient 3 in the study by Fujimoto et al. [3] , involve the osseous pathway.

Fig. 1. A: Computed tomography angiography scan showed a giant mass with rich blood supply from the bilateral occipital arteries (red arrows) and superficial temporal arteries (black arrows); B: Magnetic resonance imaging indicated an 8 × 6 × 6 cm mass in the bilateral parietal-occipital skull, with heterogeneous enhancement (white arrow); C: The general observation of tumor during the operation; D: HE staining showed adenocarcinomatous cells with tube arrangement (original magnification ×400);E: The contrast-enhanced CT of the liver indicated abnormal enhancement of the left liver (yellow arrow).

Table 1Summary of all reported cases of patients with skull metastases from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Due to the fact that morbidity from ICC is rare and the lack of data regarding the treatment of skull metastases from ICC, no standard protocol has been established. According to the literature, surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are the three most common treatment modalities [2-6] . For patients with a history of ICC resection, biopsy but not resection should be first selected to acquire pathological diagnosis before conducting the subsequent therapy. However, when isolated metastases in the skull represent the primary clinical manifestation, surgical resection with negative margins is recommended. Michael et al. [1] suggested that surgery in carefully selected calvarial patients provided effective palliation of symptomatic metastases that overlie or invade the venous sinuses. Therefore, we believe that resection should not be discouraged for the treatment of skull metastases, even that the lesions are giant or those invading the venous sinuses and skull base. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy are important adjuvant therapy methods. Radiotherapy is recommended when lesions are difficult to resect, in particular skull-base metastases [3] .However, Novegno et al. [7] performed a meta-analysis of 32 patients and found no significant effectiveness of postoperative radiotherapy in patients with brain metastases from cholangiocarcinoma. Cholangiocarcinoma remains resistant to most of chemotherapeutic agents, whereas gemcitabine, particularly in combination with cisplatin, has been shown to improve overall survival [8] . Novegno et al. [7] found that the mean follow-up time in four patients with solid central nervous system metastases was 32.7 months, which suggested that chemotherapy may signi ficantly prolong the survival length even in cases of brain metastases from cholangiocarcinoma. However, the number of patients receiving chemotherapy was only 4 out of 25 patients with solid central nervous system metastases [7] . Therefore, more clinical data are needed to confirm the exact effect of chemotherapy and radiotherapy on skull metastases from ICC.

In patients with brain metastases from cholangiocarcinoma,better results were associated with the initial treatment performed in terms of the possibility of resecting the primary tumor.Novegno et al. [7] found that 14 patients with hepatic resection had the longest mean follow-up time of 34.05 months from the first cholangiocarcinoma diagnosis; 5 patients with locoregional and/or systemic therapies had a mean follow-up time of 21.2 months; and 5 patients who did not receive any treatment had only 9.46 months. A population-based study by Yan et al. [9] also indicated that patients treated with surgery for primary and/or metastatic lesions had a better survival outcome than patients who did not have surgery. A retrospective observational study of 89 cholangiocarcinoma patients indicated that a CA19-9 level ≥103 U/mL was associated with a higher probability of metastasis and a lower rate of treatment with curative intent [10] . Therefore,in our case, elevated CA19-9 maybe an unfavorable predictor of survival.

In conclusion, we report a case of rare asymptomatic giant skull metastasis from ICC with a poor prognosis. Clinicians should consider the possibility of resection of the primary tumor and metastatic lesion. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy can be adjuvant therapies for patients with these skull metastases from ICC, while the effect on outcome requires further research.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Cheng-Dong Chang (Department of Pathology,First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine) for reviewing the pathological exams.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Man-Tao Chen:Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing -original draft.Yong-Qing Zhou:Project administration, Resources.Tian-Ya Wu:Data curation.De-Xin Cheng:Writing - review &editing.Gu Li:Project administration, Writing - review & editing.Ren-Ya Zhan:Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review &editing.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Medicine and Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province(2018ZH009) and Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province( LQ20H160040 ).

Ethical approval

Informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient families.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy before resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Human microbiome is a diagnostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Current practice of anticoagulant in the treatment of splanchnic vein thrombosis secondary to acute pancreatitis

- Enhanced recovery after surgery program in the patients undergoing hepatectomy for benign liver lesions

- Assessment of biological functions for C3A cells interacting with adverse environments of liver failure plasma