Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy before resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review

2020-05-10MinsBlttzisSnthlingmJegtheeswrnAjithSiriwrden

Mins Blttzis , Snthlingm Jegtheeswrn , Ajith K. Siriwrden , b , *

a Regional Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery Unit, Manchester Royal Infirmary, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9WL, UK

b Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9WL, UK

ABSTRACT

Keywords:

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma

Neoadjuvant

Chemotherapy

Radiotherapy

Surgery

Introduction

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (PH-CCA) is a rare bile duct cancer with poor prognosis [1] . The incidence rate of PH-CCA varies from 0.5 to 2 cases per 100000 [2,3] . Current concepts of the cancer biology of PH-CCA are that this is a fibrotic, pauci-cellular tumor with a propensity for local peri-neural and peri-vascular infiltration [1] . Clinically, although surgical resection (typically involving hepatectomy together with resection of the extrahepatic biliary tree) can be regarded as standard of care, a joint expert consensus statement issued in 2015 by the Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association (AHPBA)/Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract(SSAT)/American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) accepted that this is only feasible in a minority either because of advanced stage at presentation or co-morbidity (or both) [4 , 5] . Furthermore,even after apparently successful surgical resection the risk of recurrence remains high - at two years follow-up, the estimated probability of a recurrence was 42% in the joint report from the Amsterdam Medical Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, at five years 67%, and at eight years 76% [6] .

Dis-satisfaction with the outcomes of surgical resection led to the evaluation of liver transplantation as a treatment for PH-CCA [7] . Although liver transplantation has the theoretical attraction of achieving a complete (R0) resection, results after liver transplantation alone were disappointing [7] . The Mayo clinic group developed a protocol incorporating neoadjuvant treatment with external radiation therapy, chemotherapy with 5-fluouracil(5-FU) and internal radiation therapy followed by capecitabine up until transplantation [8] . This highly selective strategy was reported to yield a 5-year survival of 82% in patients completing the full protocol and undergoing liver transplantation [8] . These results are substantially better than the outcomes in even the best series of patients undergoing surgical resection for PH-CCA.Similar results have been reported by other centers using these highly selective pre-operative treatment protocols [9 , 10] .

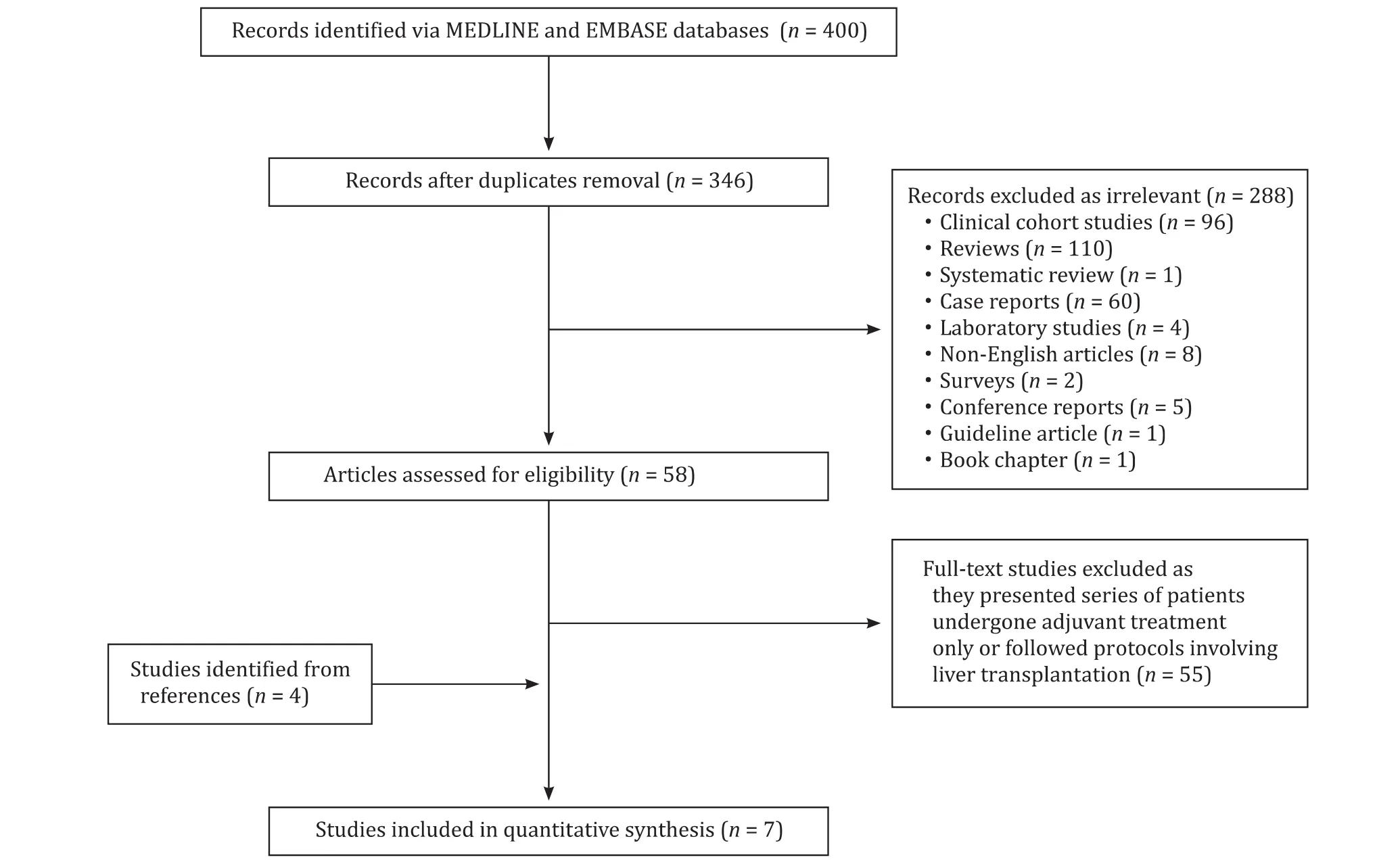

Fig. 1. PRISMA flowchart for literature search.

A critically important question remains as to whether the three components of the protocol (neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy and liver transplantation) are all required in order to obtain good outcomes in patients with localized PH-CCA or whether the neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy combination alone could similarly improve outcomes in patients undergoing surgical resection.

In 2014, Dixon’s group systemically reviewed neoadjuvant treatments including photodynamic therapy for downstaging of locally advanced cholangiocarcinoma [11] . Since that time, chemoradiotherapy has achieved greater recognition and treatments such as photodynamic therapy are no longer regarded as components of neoadjuvant protocols. Grendar et al. [11] concluded that “current evidence suggests that neoadjuvant therapy in patients with unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma can be performed safely and in a selected group of patients the neoadjuvant therapy can lead to subsequent surgical R0 resection. Surgical resection of downstaged patients should be assessed in properly designed phase II studies”.

In the current climate, adjuvant treatment for patients with resected disease has been reported to improve survival and neoadjuvant treatment followed by transplantation may improve outcome for patients with unresectable disease [12-14] . Thus, this systematic review was to focus on neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy before surgery in PH-CCA in order to assess whether phase II/III studies can be justified in current practice.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

This systematic review is to assess neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy prior to resection in patients with localized, nonmetastatic PH-CCA. Patients undergoing neoadjuvant treatment as part of a protocol leading to work-up for liver transplantation are excluded. Publications on case reports, not providing original data,or not written in English were excluded.

Information sources

A systematic review of the literature was performed using MEDLINE and EMBASE databases for publications between 1990 and 2019. The keywords and MeSH headings “hilar cholangiocarcinoma/Klatskin”, “chemoradiotherapy”and “chemotherapy”were used to yield 400 unique citations. After applying exclusion criteria, seven papers were included for further review. The PRISMA flowchart of the search strategy is shown in Fig. 1 .

Data extraction

Data were extracted on the following categories: demographic profile and disease staging, chemoradiotherapy protocols,treatment-related morbidity and outcome.

Assessment of risk of bias in individual studies

The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias [15] . Although principally designed for assessment of randomized trials, this tool has previously been used to assess case cohort series because aspects such as incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) and selective reporting (reporting bias) are applicable to cohort series [15] .

Synthesis of results

Data were extracted to populate a pre-defined series of tables addressing the clinical characteristics described above. Individualpatient survival data were used to calculate a Kaplan-Meier survival plot. Individuals who were last censored before the end of each year were not counted as survivors.

Table 1Demographic and disease profile.

Ethics review

The protocol was reviewed by the research and development department of Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Results

Risk of bias in reports

The criteria for choosing individual patients to undergo neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy are not provided and all reports exhibit selection bias. Reports do not categorize follow-up by treatment and all exhibit attrition bias. All reports demonstrate reporting bias by incomplete description of outcomes.

Demographic and disease profile ( Table 1 ) [16-22]

The median recruitment period is 14 (range 4-31) years. The total number of patients in this series is 87. Two reports from Glazer and colleagues [20] and Kobayashi et al.’s group [21] include patients who had resectable disease prior to neoadjuvant treatment.Fifty (57%) of the 87 were deemed surgically unresectable at baseline, either confirmed at prior laparotomy or CT-evidence of unresectability. Tissue confirmation of malignancy before commencement of neoadjuvant treatment was reported in four studies.

Neoadjuvant treatment protocols ( Table 2 )

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy was utilized in six reports. The chemotherapy backbone regimen was gemcitabine, either as a single agent in 1 report or in combination with cisplatin in 2. Two other reports used a fluoropyrimidine-based neoadjuvant protocol. The study by Eckmann and colleagues utilized only neoadjuvant chemotherapy with either a gemcitabine/cisplatin or oxaliplatin/cisplatin combination [19] . Sumiyoshi and colleagues used the S-1 regimen (tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil), based on a 5-FU prodrug [22] . Radiotherapy was delivered concurrently with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, fractionated to a typical pre-operative dose of 50 Gy. The study of Gerhards and colleagues used only preoperative radiotherapy in a low-dose (10.5 Gy) [17] . The interval from completion of neoadjuvant treatment to surgery varied from 3 days in the study of patients receiving low-dose neoadjuvant radiotherapy to 6 months in Glazer et al’s study where the neoadjuvant treatment was gemcitabine/platinum or 5-FU for 4 to 6 months [17 , 20] .

In addition to neoadjuvant treatment, five studies report adjuvant treatment either by chemotherapy, chemotherapy combined with external radiotherapy or brachytherapy [ 16-18 , 20 , 22] .

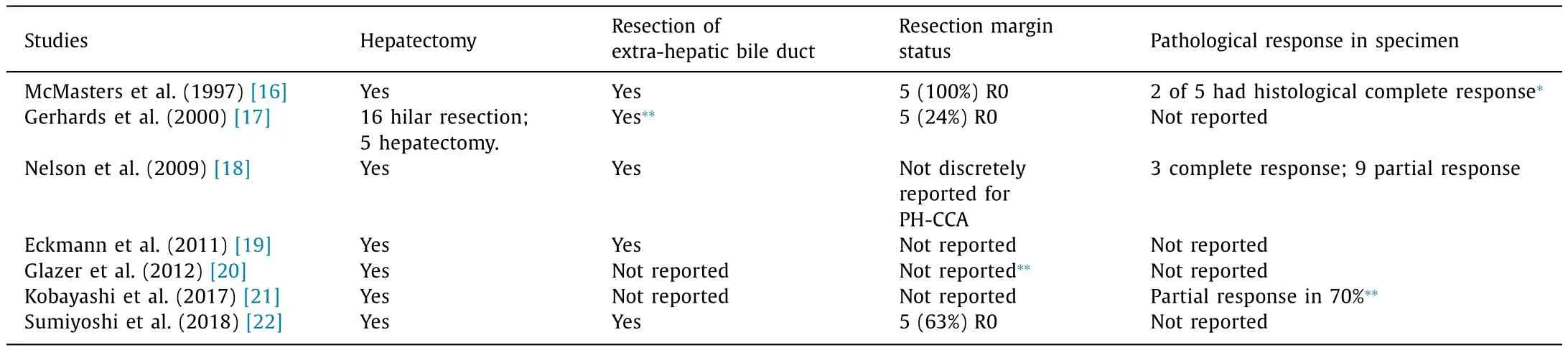

Operative detail ( Table 3 )

Hepatectomy was utilized in all reports [16-22] . Three studies reported histopathological evidence of prior treatment response [16 , 18 , 21] . The report by Nelson and colleagues included 3 patients (25% of cohort) with a complete histological response [18] .All patients who had a complete histopathological response in the resection specimen had a pre-operative diagnosis of PH-CCA. R0 resection margin status was reported in three studies (100%, 24%and 63% respectively) [16 , 17 , 22] .

Outcomes ( Table 4 )

Peri-operative morbidity was not reported by current complication reporting systems in any of the reports. There were two treatment-related deaths at 90 days. Median survival was 19 (95%CI: 9.9-28) months and 5-year survival 20%. The Kaplan-Meier survival plot is shown in Fig. 2 .

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review focused on neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy before resection of PH-CCA. Although the reports originate from recognized cancer centres, this study shows that the pooled data reported here which also constitute part of the review reported by Grendar et al. in 2014 [11] are at high risk for selection, attrition and reporting bias. The rarity of resectable PH-CCA is illustrated by the median recruitment period of 14 (range 4-31) years. This long recruitment period means that there are likely substantial differences in care within reports in addition to the variations among centers. There is also important variation in the type of surgical treatment undertaken and in the reporting of outcome after surgery.

Unlike the Mayo protocol of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy before liver transplantation, it is clear that there is no standard neoadjuvant treatment protocol before surgical resection. Neither case selection criteria nor treatment protocols are standardized.

Yet it is important not to dismiss these data as the study highlights some important and arguably unique aspects of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy before resection of PH-CCA. First, there is the suggestion in some reports that neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy may facilitate a subsequent R0 resection [16 , 17 , 22] . This may be of importance in a disease where it can be difficult to achieve clear surgical margins after resection. Second, there is anevidence in some reports of a histopathological response to treatment [16 , 18 , 21] . The frequency of complete R0 resection after neoadjuvant chemo(radio)therapy is worthy of further study in a phase II protocol.

Table 3Operative detail and histology.

Table 4Outcome.

It is important to note that as the focus of the reports in this review is on patients who successfully underwent resection.Thus, patients who underwent neoadjuvant treatments but did not progress to surgery were not reported in this review. This assessment of treatment response might be important in future trial design.

Fig. 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curve for patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemo/radiotherapy for PH-CCA. Data are based on 32 patients in whom individual outcome data were available.

Thus can the results of these data be utilized in the development of phase II/III studies as recommended by Dixon and colleagues in their review? The clinical evidence base has changed since that time and this must be acknowledged. First, the recently reported BILCAP phase III study of adjuvant capecitabine compared to observation after resection of cholangiocarcinoma(including PH-CCA) shows that although the adjuvant chemotherapy arm failed to achieve statistical significance in a superiority design, the improvement in median survival associated with adjuvant capecitabine to 54 months from a median survival of 36 months in patients not receiving adjuvant treatment is clinically significant [12] . This has led to the recent practice guideline by the American Society for Clinical Oncology that patients with resected biliary tract cancer are offered adjuvant capecitabine chemotherapy for 6 months as standard of care [23] . The data reported here are heterogeneous and at best non-inferior to resection alone and apparently inferior to resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy.

Current practice in Europe would be to offer patients with resected biliary tract cancer the option of the adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin compared to standard of care after curative intent resection of biliary tract cancer (ACTICCA-1)study [24] . This study compares gemcitabine and cisplatin to the newly established standard regimen of capecitabine monotherapy in patients with resected biliary tract cancer. Similarly, the evidence in relation to management of locally advanced, unresectable,non-metastatic PH-CCA has changed with the emergence of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and liver transplantation as a viable option in this setting [10 , 25] .

Scientific equipoise exists in relation to the question of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for PH-CCA. However, practical and patient-focused ethical restraints restrict the advisability of developing such a study. The heterogeneity of chemoradiotherapy regimens reported in this review illustrates the wide range of treatments in use and also highlights the difficulty in selecting a single protocol for any future study. In practice, there may be a contemporary niche for evaluation of the Mayo pre-transplantation chemoradiotherapy protocol in a prospective phase II evaluation in patients with borderline resectable, non-metastatic, cytologically or histologically confirmed PH-CCA in healthcare systems which have not adopted the Mayo liver transplantation protocol.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Minas Baltatzis:Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing -original draft.Santhalingam Jegatheeswaran:Formal analysis,Methodology, Writing - original draft.Ajith K. Siriwardena:Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

The protocol was reviewed by the research and development department of Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Human microbiome is a diagnostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Current practice of anticoagulant in the treatment of splanchnic vein thrombosis secondary to acute pancreatitis

- Enhanced recovery after surgery program in the patients undergoing hepatectomy for benign liver lesions

- Assessment of biological functions for C3A cells interacting with adverse environments of liver failure plasma

- Transarterial chemoembolization versus percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy for recurrent unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Development of a prognostic nomogram