Current practice of anticoagulant in the treatment of splanchnic vein thrombosis secondary to acute pancreatitis

2020-05-10WillimNortonGbijLzrviiuteGeorgeRmsyIreneKreisIrfnAhmedMohmedBekheit

Willim Norton , Gbij Lzrviiute , George Rmsy , b , Irene Kreis , Irfn Ahmed ,Mohmed Bekheit , d , *

a Department of General Surgery, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen AB25 2ZN, UK

b Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health, University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill, Aberdeen AB25 2ZD, UK

c Clinical Effectiveness Unit, Royal College of Surgeons of England, 35-43 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Holborn, London WC2A 3PE, UK

d Department of Surgery, El Kabbary Hospital, El Kabbary, Alexandria, Egypt

ABSTRACT

Keywords:

Severe acute pancreatitis

Splanchnic vein thrombosis

Anticoagulant therapy

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is a common cause of emergency admission to general surgical departments across the world. It has an incidence of 13-45 per 10 0,0 0 0 of the UK population [1] . Pancreatitis has a spectrum of severities and related mortality with severe acute pancreatitis being associated with mortality rates of greater than 40% [2] . Sequelae of this condition includes multi-organ failure, intra-abdominal collections, and thrombosis of the splanchnic veins including splenic, superior mesenteric and portal veins [3] .

Splanchnic vein thrombosis has been shown to be a complication in more than a fifth of cases with severe acute pancreatitis [4] . The etiology is postulated to be the pro-thrombotic nature of the acute inflammatory condition, with contributions from the systemic response to the injury, hypovolemia and fluid shifts [5] .Without treatment, the thrombus can precipitate bowel ischemia,hepatic failure or chronic portal hypertension [6] . Accordingly, anticoagulation would seem a necessity in these cases. However, this could bring about significant risks such as bleeding. Patients with severe acute pancreatitis are also at risk of bleeding. This can be into the retroperitoneum or from pseudo-aneurysms of major vis-ceral arteries [7] . Such bleeding could be catastrophic in the context of an anticoagulated patient [8] .

Thus, the risks versus benefits of anticoagulation in the treatment of splanchnic vein thrombosis are unknown and is not well evaluated in the literature. Indeed, the answer to this question remains entirely in equipoise with no simple answer available from basic surgical first principles or from the literature. Although clearly reported as a complication of acute pancreatitis, there appears little direct studies or guidance on the preferential management of this condition.

This systemic review aimed to explore the current published literature on whether the data is sufficient to recommend anticoagulation in this setting or to advocate its avoidance. This subject has particular relevance to emergency general surgery - a specialty with less supporting evidence than its better established comparators [9] .

Methods

This is a systematic review in which the PRISMA checklist was utilized and standard review techniques observed. The protocol has been registered prior to starting the systematic review process and can be found on the PROSPERO register (ID: CRD42018102705).This project was supported by the Royal College of Surgeons of England Systematic Review Team.

Eligibility criteria

A focused review question was identified prior to searching using the population, intervention, comparison and outcomes (PICO)framework. Selected population was individuals with splanchnic vein thrombosis in acute pancreatitis (irrespective of the cause of pancreatitis). The population were all adults (patients aged over 18 years old) who had the above-defined disease. Intervention arm included therapeutic anticoagulation (including interventional techniques). Control arm were those individuals within the population who were not treated with therapeutic anticoagulation (this included those with prophylactic doses of low molecular weight heparin). Primary outcomes were recanalization versus bleeding complication, mortality and length of hospital stay. Relevant studies were included irrespective of the study type, publication year or language of publication. Translation facilities were utilized where appropriate.

Search strategies

Electronic searches were performed on MEDLINE, EMBASE,PubMed, Cochrane and Web of Science databases. Searches were two-fold to allow identification of all currently available studies and ensure none were missed. (1) A broad search strategy for each of the above database, simply using terms ‘pancreatitis’ and ‘anticoagulation’ -this allowed identification of a broad number of studies. (2) A MeSH constructed search strategy which was similar for each of the databases, this allowed more relevant studies to be identified, however due to paucity of results available on the subject currently, strategy 1 was also utilized to ensure no relevant studies were missed out. Exact match of the search strategies was not possible due to differences in interface between the search algorithms of the individual databases.

Three authors (Norton W, Lazaraviciute G and Ramsay G) performed the searches and any difference in opinion when including studies were resolved through team discussion. Authors of studies that appeared relevant, but were missing of essential information,were contacted via E-mail, with a two-week deadline for response given. A log of each search was kept by exporting them into the Rayyan platform ( www.rayyan.qcri.org ).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were reviewed at title, abstract and full-text stage and were included or excluded accordingly depending on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria: (i) all other reports on the use of this intervention (anticoagulant) in the abovede fined population; (ii) studies on adults (age>18 years) only. Exclusion criteria: (i) studies on chronic pancreatitis; (ii) studies on pancreatitis after pancreatic resections or transplant; (iii) animal studies.

Study selection and data extraction

A flowchart was created to display number of studies included and excluded at each review stage ( Fig. 1 ). Three authors (Norton W, Lazaraviciute G and Ramsay G) performed the process separately and any disagreements in the outcomes were resolved through team discussion. A cloud based data extraction template was used to facilitate data collection. The data extraction template was designed by input from all authors. During the data extraction process, quality of included studies was also assessed using the Downs and Black checklist [10] . The Downs and Black assessment tool was performed on each of the studies to give a quantitate assessment of the evidence available. The original criteria for the final question was modified to only give a response of “1”if a power calculation was used. The use of “0”in the chart was used for both a no response and unable to determine.

Results

Of 1462 papers assessed, a total of 16 studies were included in the systematic review. Fig. 1 shows the flowchart for these searches. None of the studies were randomized controlled trials.Nine studies were case reports, 2 were case series and the remainder were retrospective single-center studies. There were a total of 198 patients in these studies of whom 92 (46.5%) received anticoagulation therapy. The rates of recanalization of veins in the treated and non-treated groups was 14% and 11% and bleeding complications were 16% and 5%, respectively. However, a metaanalysis was not performed due to the lack of high quality studies.

Single-center studies

There were 5 single-center studies included in the review, summarized in Table 1 , with a total number of 182 patients. Due to the paucity of studies and their significant differences, meta-analysis and synthesis of results was not deemed possible.

Gonzelez et al. [6] reported 20 patients in which 4 were treated.No hemorrhagic complications due to anticoagulation and little difference between cavernoma formation (porto-portal shunts) rates were observed. However, those treated had a lower rate of developing other collateral vessels in this study. Harris et al. [11] described their experience of splanchnic vein thrombosis in 45 patients with acute pancreatitis, the majority occurring solely in the splenic vein. Of 17 patients that were treated with anticoagulation,only 2 had recanalized vessels (12%), and a similar rate for those that were not treated (11%). The timing of this recanalization was not mentioned in this paper. Bleeding complications were observed in 5 patients, with only 2 on anticoagulation at the time.

Toqué et al. [12] performed a retrospective analysis of 19 patients. The majority (79%) received therapeutic anticoagulation with 26.3% achieving complete recanalization. No significant bleeding complications were reported. Garret et al. [13] reviewed a cohort of 76 patients who had been admitted to an intensive care unit and had reports a 26% rate of a bleeding complication in those treated with systemic anticoagulation. Treatment did not prevent the formation of cavernoma in this group of patients.

Fig. 1. Flowchart diagram.

Table 1Individual center studies.

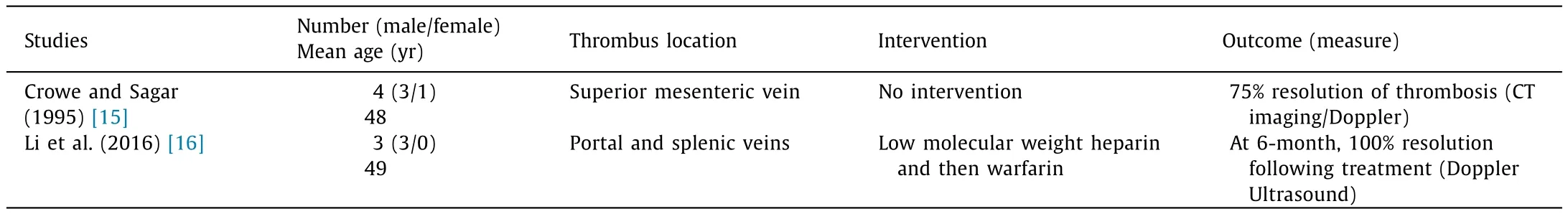

Table 2Case series.

In 2014, Easler et al. [14] analyzed 22 patients who developed splanchnic vein thrombosis following acute pancreatitis, with the thrombosis again predominantly occurring in the splenic then portal veins. No patient had treatment specifically for the thrombosis but two had a bleeding complication, whilst one of these was on anticoagulation (for another cause). No complication was attributable to the thrombosis.

Case series

There are two defined case series ( Table 2 ) describing 7 patients(6 males/1 female) with a mean age of 48.4 years old. Crowe and Sagar [15] described 4 case of superior mesenteric vein thrombus,which were not treated with any anticoagulation. On follow-up imaging, 3 had completely resolved. The patient who had not had resolution on 3-month CT imaging, remained well during study follow-up of 5 years. Conversely, Li et al. [16] report 3 cases with both splenic and portal vein thrombosis, with resolution in all 3 cases following treatment with low molecular weight heparin and subsequent warfarin therapy. They were able to report no complications and describe this treatment as safe.

Case reports

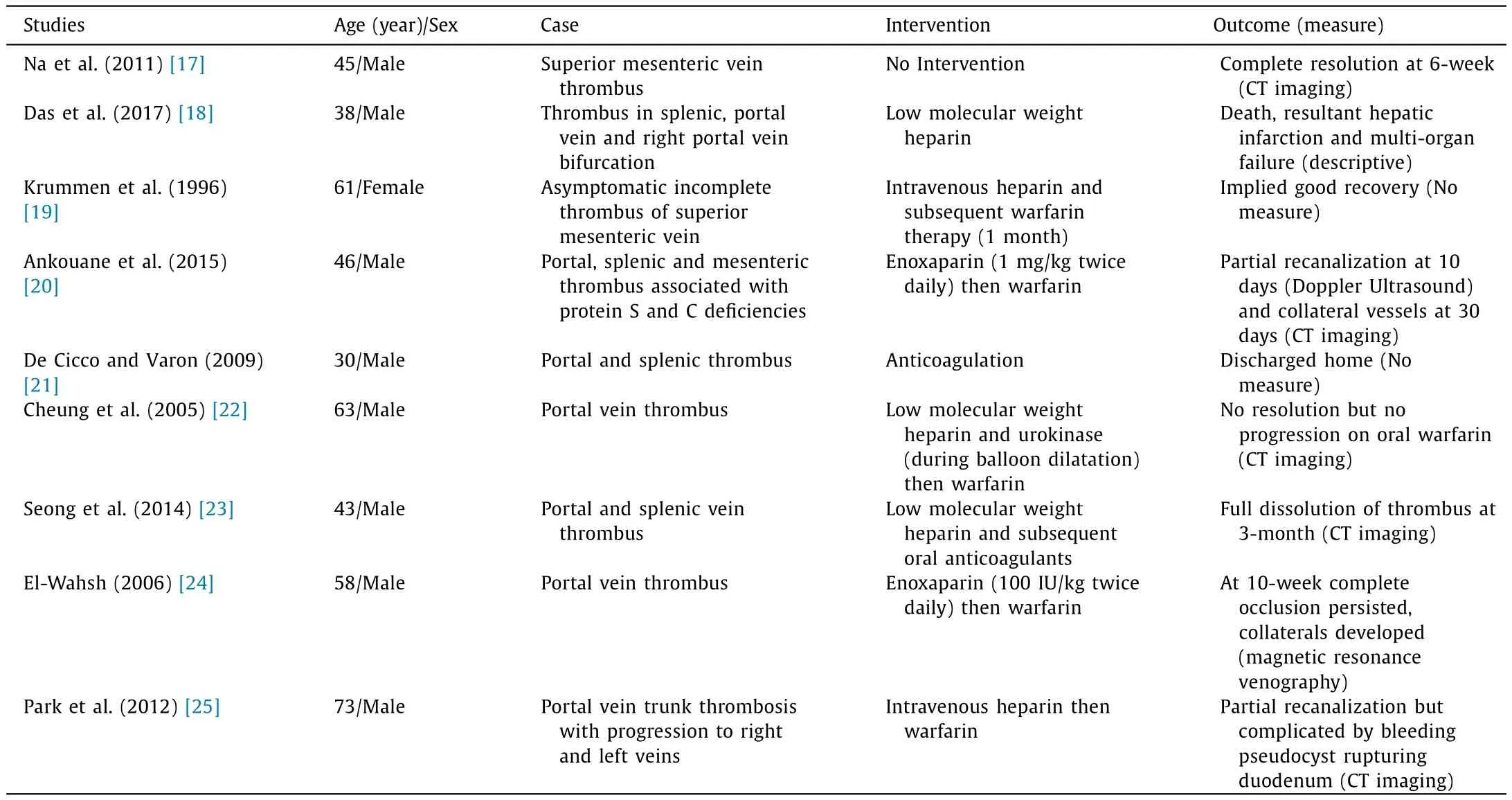

Of the 9 case reports ( Table 3 ), the majority are male with a median age of 46 years (range 30-73). The location of thrombus in these reports is predominantly in the portal vein (67%), with both splenic and mesenteric occurring in 4 (44%). Eight of the reports depicted an intervention with the use of either unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin and subsequent warfarin the most commonly used in 5 cases. The other three either used just low molecular weight heparin, had the addition of urokinase or only defined their intervention as “anticoagulation”.

Three of those treated had favorable objective outcomes either with partial recanalization or complete resolution, whilst two showed either no resolution or complete occlusion. Two had positive subjective reviews of recovery. One patient died of hepatic infarction and multi-organ failure. One of the patients treated with unfractionated heparin and warfarin developed bleeding into a pseudocyst. Although the majority of the case reports suggested treatment, Na et al. [17] indicated complete resolution of a mesenteric vein thrombus, with no surgical or medical intervention.

Quality control

Table 4 lists the quality assessment of each of the papers included and demonstrate a paucity of quality studies available in the literature. The average score overall for all 16 studies was 7.3/28.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to address whether anticoagulation should be given to patients with mesenteric vein thrombosis in severe acute pancreatitis. It has been undertaken in a logical, meticulous fashion and only 16 papers of relevance were identified. If the epidemiological estimates of thrombosis in severe acute pancreatitis are accurate [4] , this is a common sequelae of acute pancreatitis and it was unexpected that there was a lack of high quality studies addressing this issue. As a consequence, it is difficult to recommend one treatment over the other for splanchnic vein thrombosis in acute pancreatitis using a synthesis of the currently published literature as no meta-analysis was possible.

The findings of our analysis of relevant publications are that,in this population of patients, 92 (46.5%) received anticoagulation.Recanalization and bleeding complications were observed in a proportion of both comparison groups (treatment versus no treatment). Therefore, there is little trend towards the appropriate management strategy. Indeed, most authors of the included studies portrayed their own inferences from their study series and all acknowledge the lack of guidance from previous publications. There was also significant heterogeneity of the splanchnic vein thrombosis associated with patients who have developed pancreatic necrosis [14] .

The most common location is in splenic vein. However, the portal vein and superior mesenteric veins can also be involved. It is thus unclear as to whether the treatment strategy would alter given the anatomical location of the thrombus. The portal vein thrombus has been used as an indicator of severity due to the risk of impaired liver function, and has been shown to have a predominance for treatment with anticoagulants [6] . This is despite no difference in eventual recanalization rates. Whilst these could be considered as deep vein thrombosis, the added complicating factor is the risk of significant retroperitoneal bleeding and potential exsanguination.

Another critical question is what defines a thrombosis. Again,there is heterology between the studies. Harris et al. [11] and Garret et al. [13] defined splanchnic vein thrombosis as either visualizing thrombus in the vein or if the vein was compressed or was not visualized with the presence of collaterals. Easler at al. [14] differentiated thrombosis from narrowing in their study. Others did not specify the diagnosis criteria for splanchnic vein thrombosis. Such a definition would be required in any future prospective study as anticoagulation treatment efficacy could differ depending on the presence of thrombus within a vein and complete occlusion of the vessel.

Almost all of the anticoagulation used in this setting was either low molecular weight heparin or warfarin. Indeed, only one publication reported on a different agent -urokinase [22] . In other settings, such as patients who have atrial fibrillation and deep vein thrombosis, novel anticoagulants have become commonplace in clinical practice. There are advantages in the lack of requirement for therapeutic level testing [26] . However, given that there are few reversal agents [27] , and they rely upon regular oralabsorption [26] which can be compromized in pancreatitis, they cannot be recommended in this setting. Our search strategy encompassed any publication potentially using these agents and did not find any.

Table 3Case reports.

Table 4Downs and black.

That this question has yet to be answered in any of the literature is perhaps intriguing. It is a common problem and one which treatment seems to be occurring on the basis of clinician’s opinion rather than with an evidence base. As such, the treatment remains entirely in equipoise and a randomized controlled trial may assist in establishing the correct management course. To our knowledge,no such trial is being undertaken or planned. However, any such randomized controlled trial would need to be appropriately powered and likely to be multi-center in nature. As patients with severe acute pancreatitis are having their care more commonly undertaken in specialized centers, this is not unfeasible in modern surgical management.

The strengths of this work are the rigorous nature in which the systematic review was performed. We have been able to carefully dissect the literature and undertake, what we believe, to be a comprehensive search. Although the intention was also to attempt to perform a meta-analysis of the available results, we were aware of potential challenges from the start due to predicted paucity of studies on the subject which is an acknowledged limitation.

In conclusion, the available literature is of limited quality and it is not clear whether the therapeutic anticoagulation is necessary or required in cases with severe acute pancreatitis associated with splanchnic vein thrombosis. Given the potential morbidity and mortality concerns with either under-treatment or the consequence of bleeding whilst on treatment, this question is clinically relevant and one which will require randomized controlled studies to address.

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. Katsunori Imai (Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Graduate School of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University,Kumamoto, Japan) for help with translating some studies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

William Norton:Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.Gabija Lazaraviciute:Data curation, Formal analysis,Writing - original draft.George Ramsay:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing - original draft,Writing - review & editing. Irene Kreis: Methodology, Writing -original draft.Irfan Ahmed:Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing.Mohamed Bekheit:Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Not needed.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy before resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Human microbiome is a diagnostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Enhanced recovery after surgery program in the patients undergoing hepatectomy for benign liver lesions

- Assessment of biological functions for C3A cells interacting with adverse environments of liver failure plasma

- Transarterial chemoembolization versus percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy for recurrent unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Development of a prognostic nomogram