Higher body mass index deteriorates postoperative outcomes of pancreaticoduodenectomy

2020-05-10SiYiZouWeiShenWangQianZhanXiaXingDengBaiYongShen

Si-Yi Zou , Wei-Shen Wang , Qian Zhan, Xia-Xing Deng, Bai-Yong Shen

Pancreatic Disease Center, Research Institute of Pancreatic Disease, Shanghai Institute of Digestive Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai 200025, China

ABSTRACT

Keywords:

Body mass index

Obesity

Overweight

Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Introduction

The prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased over the past decade in almost all age groups and genders all over China [1-3] . According to the latest national investigation, the overweight and obesity rates have increased from 22.8% to 30.1%and 7.1% to 11.9% between 2002 and 2012, respectively [4] . The rapid development of overweight and obesity will undoubtedly push up the morbidity of obesity-related chronic disease such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease and several malignancies including breast, prostate, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer [5-8] . Recent studies also suggested its significant association with worse outcomes after surgery [9 , 10] .

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is considered a safe, potentially curative surgical treatment for tumors confined to the pancreatic head, distal bile duct, and periampullary region of the duodenum [11] . The mortality of PD has declined to below 3% due to centralization of the procedure in high-volume centers [7 , 12 , 13] .Despite the advances in surgical techniques, standardized postoperative management and improved radiological interventions, morbidity rates still remain as high as 20% -50% [14] .

Numerous studies [15-23] have been carried out to explore the correlation between body mass index (BMI) and morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing pancreatic surgery. Higher BMI is perceived to be a risk factor for intra- and postoperative unfavorable incidents, such as longer operative time, more intraoperative blood loss, higher rates of wound infection and pancreatic fistula,and longer postoperative hospital stay [15-23] . However, most of the aforementioned studies remain limited by grouping overweight of BMI 25.0-29.9 kg/m2, and obese, BMI ≥30 kg/m2, as these cut-offs were defined based on studies involving Western population. World Health Organization (WHO) International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) has recommended the lower cut-offs of BMI ≥23 kg/m2for overweight, and ≥25 kg/m2for obese for Asian people [24] . A 10-year retrospective analysis in China showed individuals with BMI ≥24 kg/m2were more likely to suffer from worse outcomes, but it did not describe the surgical methods [25] . Thus,in this retrospective study of Chinese patients, we aimed to assess outcomes after PD in obese patients and compare them with those in normal weight and overweight patients.

Patients and methods

Patient selection and data collection

From January 2005 to December 2016, 745 adult patients who underwent open PD in the Pancreatic Disease Center at Ruijin Hospital, with retrievable pathological, BMI data and perioperative parameters, were included in this study.

BMI was calculated as a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). For this analysis, patients were categorized according to BMI: obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2),overweight (BMI ≥23 kg/m2and<25 kg/m2), or normal weight(BMI ≥18.5 kg/m2and<23 kg/m2), based on WHO IOTF definitions [24] , and those with BMI<18.5 kg/m2were excluded.

Preoperative data were collected, including demographics(i.e., age, sex, and medical history), preoperative clinical history,laboratory investigations, prior imaging studies, and preoperative therapies (i.e., preoperative biliary drainage). Intraoperative parameters included total blood loss, operative time, blood transfusion,pathology of resected tumors, and use of pancreatic duct stents.The postoperative clinical sequel was assessed by therapeutic and diagnostic strategies, nutritional support, laboratory and imaging studies, recovery of gastrointestinal function, specific types of postoperative complications, duration of drain placement,postoperative hospital stay, re-operations, and mortality.

Surgery procedures

Patients undergoing surgery was explored for respectability. All the surgeries were open and conducted by experienced surgeons.Kocher’s incision was made for free mobilization of descending and transverse parts of duodenum along with posterior pancreatic head. PD was performed along with the resection of gallbladder, common hepatic duct, head of the pancreas, duodenum and the antrum of the stomach near the left gastric artery. The head of the pancreas was transected exposing the portal vein and superior mesenteric vein. We performed pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ)by the duct-to-mucosa method with eight interrupted sutures of 5-0 PDS-II (polydioxanone; Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA). An endto-side cholangiojejunostomy was then performed 8-10 cm distal from the PJ. Finally, end-to-side gastrojejunostomy 50-60 cm distal to cholangiojejunostomy, was performed to place the stomach into a straight vertical line through the retrocolic route. Closed drains were inserted behind the cholangiojejunostomy and at the upper side of the PJ.

Perioperative management

All patients received prophylactic antibiotics for 3 days, H2blocker or proton pump inhibitor to prevent stress peptic ulcer and octreotide analogs. Close observation of vital signs, electrolyte balance, 24 h urine output, postoperative laboratory investigations,drain analysis were noted. All patients had drain removed at operating surgeon’s discretion. Drains were removed if amylase level were below 3 times the serum amylase in absence of any symptomatic clinical manifestations. They were maintained longer when drain amylase was higher with sinister appearance as defined in the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) scheme as “varying from a dark brown to greenish bilious fluid to milky water to clear spring water that looks like pancreatic juice”[26] .Radiologic interventions with diagnostic CT imaging were used for patients to access intra-abdominal fluid collection.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using SPSS software, IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous data were expressed as mean with standard deviation or median with range according to data distribution, whereas categorical data were expressed as percentage. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to detect of abnormally distributed continuous variables. In cases of significant differences, the post-hoc test was applied to verify the differences. The associations between different categorical variables were assessed using the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Stepwise multiple linear regression analysis and multiple logistic regression were used to assess the impact of BMI on postoperative outcomes. APvalue<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographics and preoperative variables

A total of 745 patients who underwent PD were identified. After excluding the patients with BMI<18.5 kg/m2, 707 patients werefinally included in this study. Characteristics of the patients,grouped according to BMI, are presented in Table 1 . Among preoperative laboratory investigations, the overweight and obese groups had significantly higher levels of hemoglobin concentrations (g/L)(123.34 vs. 129.76 vs. 129.66,P<0.001). Cardiovascular disease was more common in obese (23.9%) and overweight patients (13.5%)compared to the normal weight cohort (10.6%) (P<0.001). No significant difference was found among the BMI groups regarding age,sex, clinical history (i.e., pancreatitis, history of abdominal surgery,diabetes), other preoperative laboratory data (i.e., white blood cell count, serum albumin, serum total bilirubin), pancreatic duct dilatation, preoperative pathology diagnosis, or preoperative biliary drainage.

Operative procedure and pathology

The operative and pathology details are presented in Table 2 .Operative time, intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative blood transfusion, combined resection or reconstruction of vein, and pancreatic duct stenting were not significantly different among BMI groups.

All the resected specimens were sent for pathologic evaluations.Most of the operations (588, 83.2%) were performed for malignant cases. Resections were also performed for benign (n= 23) and borderline (n= 96) tumor lesions. There was no significant difference among the BMI groups in malignancies, tumor size, or number of lymph nodes harvested.

Postoperative outcomes

Postoperative hospital stay in obese patients [23 (8-121) d] was significantly longer than that in overweight [19 (7-158) d] and normal weight patients [19 (2-84) d] (P= 0.023). The length of bilioenteric (BE) drain placement were 11 (1-70), 11 (1-64), and 12(1-70) d (P= 0.046) and that for drain duration beside the PJ were 12 (1-53), 13 (2-96), and 15 (1-127) d (P= 0.005) for normal weight, overweight, and obese patients, respectively.

A significantly higher rate of postoperative morbidities was often observed in the overweight and obese groups. The clinicallyrelevant postoperative pancreatic fistula (CR-POPF) showed significant increase trend among the three categories (7.6% vs. 9.9%vs. 17.6%,P= 0.002). An increasing but not significant trend of SIRS rates was identified in the three groups (37.2% vs. 38.5% vs.44.9%,P= 0.215). The duration of SIRS was significantly longer among patients in the obese category than among the patients in the normal weight and overweight category [2 (1-9) vs. 2 (1-7)vs. 3 (1-10),P= 0.003]. For re-operation, obese patients displayed significantly higher rates compared to the normal weight patients(1.1% vs. 5.1%,P= 0.006), and the rate in overweight patients(2.5%) was also higher than in normal weight patients, but without significant difference. Besides this, biliary leakage, gastrointestinal fistula, delayed gastric emptying grades, intra-abdominal infection,intra-abdominal hemorrhage, other complications and mortality were similar across the three groups ( Table 3 ).

Table 1Characteristics of patients grouped according to BMI.

Seventeen out of 707 patients experienced re-operation and six died in hospital. The main cause of re-operation was intraabdominal hemorrhage (11/17, 64.7%);five underwent debridement caused by intra-abdominal infection, and one underwent aneurysmectomy for a left femoral pseudoaneurysm. Most patients recovered well, except one patient, who died of multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome 12 days after debridement. The other causes of hospital death were septic shock (2/6), hemorrhagic shock (2/6),and heart failure (1/6).

Prognostic factors of postoperative incidents

We included variables in a multiple linear regression analysis( Table 4 ) to analyze the prognostic factors related to postoperative hospital stay, duration of SIRS, PJ drainage removal, and BE drainage removal. After adjusted for confounders, the results suggested that BMI was linearly correlated with postoperative hospital stay (estimates 0.965, 95% CI: 0.292-1.638,P= 0.005). Blood loss (estimate 0.003, 95% CI: 0.000-0.005,P= 0.020), duration of PJ drain (estimate 0.733, 95% CI: 0.585-0.882,P<0.001), infection(estimate 6.496, 95% CI: 3.585-9.406,P<0.001) and re-operation(estimate 7.792, 95% CI: 0.128-15.456,P= 0.046) were also found to be linearly correlated with postoperative hospital stay. There was no significant linear dependence between BMI and duration of SIRS, BE or PJ drainage removal (P= 0.087,P>0.1,P= 0.183,respectively). The analysis results demonstrated cardiovascular disease, biliary leakage and infection (allP<0.05) were risk factors for duration of SIRS. Operative time, biliary leakage, infection, CRPOPF and other complications were positively related to duration of BE drain (allP<0.05), and history of abdominal surgery, operative time, blood loss, delayed gastric emptying, intra-abdominal hemorrhage, infection, CR-POPF and other complications were positively related to duration of PJ drain (allP<0.05) (Data not shown).

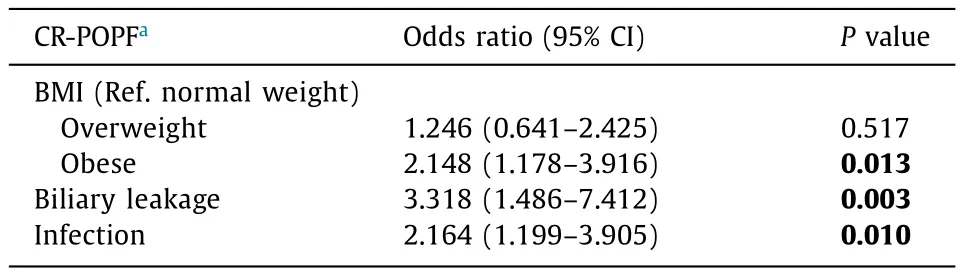

To evaluate the impact of obesity on CR-POPF, we included perioperative parameters in multiple logistic regression analysis. The results confirmed obesity (P= 0.013), biliary leakage (P= 0.003)and infection (P= 0.010) were independent risk factors for CRPOPF ( Table 5 ).

Discussion

The WHO data demonstrated that prevalence of obesity has tripled since 1975, displaying a pandemic magnitude worldwide of rising tendency. Obesity has become a public health care crisis and approximately 3.4 million adults die from overweight and obesity each year [25] . There was already some data relating obe-sity with unfavorable intra- and postoperative incidents [27 , 28] .Dhar et al. [29] and Görög et al. [30] considered obesity an adverse factor in impaireden-blocresection of gastric and rectal cancers.Currently, a variety of studies have been carried out to assess the impact of BMI on morbidity and mortality from pancreatic surgery.However, these results did not reach complete agreement, partly because the available data was collected from a single-center or in small volume, processed ignoring the different surgery patterns, or grouped by BMI of different cut-off values. Despite that Gaujoux et al. [31] demonstrated no statistically significant differences in intraoperative or perioperative outcomes among groups divided by the WHO BMI cut-offs, our study is consistent with other studies [15-23] that overweight and obese patients have worse perioperative outcomes.

Table 5Multivariate logistic regression analysis on predictors of CR-POPF.

Sahakyan et al. [32] implicated obesity as an adverse factor in increased prevalence of comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Shimizu et al. [33] suggested that overweight/obesity was a risk factor for pulmonary complications. In this study, we only found an increasing rate of coronary heart disease in overweight and obese patients. Obesity has been reported to be associated with increased blood loss and longer operative time in PD [15-18 , 20 , 27 , 28 , 34] . But no difference existed among three groups in our study, probably owing to the skilled surgeons.

Overweight/obesity was identified as a risk factor of POPF in several previous studies in spite of the surgery procedures [16 , 20-23 , 32] . Sahakyan et al. [32] and Sledzianowski et al. [35] both found elevated POPF rates in obese patients compared with normal weight patients after distal pancreatectomy.Tsai et al. [16] emphasized the adverse impact of obesity on POPF in patients with malignancy after PD. Our study showed that the incidence of CR-POPF displayed significantly increase among normal, overweight and obese patients regardless of pathology and that multiple logistic regression analysis confirmed obesity as an independent risk factor of CR-POPF, which was in line with other studies [16 , 20-23 , 32] . Former studies [13 , 21] showed that the increase of fatty infiltration, correlated with high BMI in some way,was responsible for higher incidence of POPF, which might explain the present results. The present study verified biliary leakage and infection the other two risk factors for CR-POPF. Chen et al. [25]revealed that patients with BMI ≥24 kg/m2exhibited a greater incidence of bile leak and several studies [18 , 19] stated higher risk of wound infection in patients with higher BMI. Our analysis observed increased likelihood in biliary leakage and infection among three groups without significant difference, but our prospective records showed that obese and overweight groups needed signi ficantly longer use of two drains (nearby biliary-enteric anastomosis and PJ) than the normal weight patients, which correspond to the earlier drain removal in normal weight patients than in the obese mentioned in El Nakeeb et al.’s study [23] .

Numerous studies investigated delayed gastric emptying [20 , 23 , 25 , 36] ; however, the majority of these results were negative. Our study was in accordance with those studies. In contrast, Chen et al. [25] observed an elevated risk of delayed gastric emptying in overweight/obese patients, with the cut-off BMI at 24 kg/m2, which differed from the WHO IOTF redefinition.

It has been verified by in vitro and animal model studies that obesity is associated with low-grade systemic inflammation, and higher BMI or higher intra-abdominal fat content might contribute to worse perioperative outcomes, due to insulin resistance,obesity-associated chronic inflammation, or adipose-tissue secretion of hormones associated with metabolic syndrome [37-39] .A certain number of studies showed that patients with high BMI experienced a high-risk of wound infection [18 , 19] . Arismendi et al. [39] found that systemic inflammatory response in morbid obese patients was strong, with high levels of adiponectin,C-reactive protein, interleukin (IL)-8, IL-10, leptin, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (sTNF-R1), and 8-isoprostane, which became ameliorated after bariatric surgery. Andruszkow et al. [40]indicated presentations of the highest levels of C-reactive protein and increased systemic IL-6 levels until day four in high BMI patients with multiple traumas. Although there was no significant difference in the incidence of SIRS among the three BMI categories,we observed longer duration of SIRS in obese category compared with normal and overweight categories. Cardiovascular disease,biliary leakage and infection, which were frequently observed in overweight/obese groups, were also predictive factors. Prevenient studies thought perioperative blood transfusion lowered immunity and led to infectious complications [41-44] , but our study did not find their correlation. On the contrary, our study suggested that higher BMI was associated with increased trend of re-operation,the significant difference of which was not observed in other studies [23 , 25] .

El Nakeeb et al. [23] reported a significant increase in the hospital stay of overweight patients in comparison to normal weight patients, and they attributed the better outcomes among normal weight patients to lower morbidity, earlier oral feeding, and shorter drain duration. Our results also revealed that postoperative hospital stay significantly prolonged with BMI. Meanwhile, blood loss, duration of PJ drain, infection and re-operation, which might contribute to unfavorable postoperative outcomes, were positively correlated with postoperative hospital stay. Tsai et al. [16] reported that obese patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing PD had higher postoperative mortality, whereas the mortality in our analysis did not differ significantly among the three series.

There are some limitations in this study. The retrospective nature might result in selection bias and misclassification bias. The three groups were divided based on the WHO IOTF redefinition in Asia population, which differed from previous studies. Besides, as mentioned in other studies, we did not collect the original weight of the patients with a history of weight loss. Some studies proposed that the visceral fat area should be taken into account together with BMI to assess the actual fat distribution [31 , 32] . However, related data were not collected in our study.

In conclusion, the data confirmed PD as a safe surgery procedure for patients with high BMI. However, it is necessary to conduct pharmacological prophylaxis and high-quality postoperative management protocols that prevent postoperative complications like POPF in the care of overweight/obese patients, because most people are unlikely to slim down before surgery.

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. Cheng-Hong Peng (Ruijin Hospital) for giving many helpful suggestions of the manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Si-Yi Zou:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis,Methodology, Writing - original draft.Wei-Shen Wang:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing -original draft.Qian Zhan:Methodology, Writing - review & editing.Xia-Xing Deng:Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing.Bai-Yong Shen:Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy before resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Human microbiome is a diagnostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Current practice of anticoagulant in the treatment of splanchnic vein thrombosis secondary to acute pancreatitis

- Enhanced recovery after surgery program in the patients undergoing hepatectomy for benign liver lesions

- Assessment of biological functions for C3A cells interacting with adverse environments of liver failure plasma