建筑对非城市空间观念定义的贡献

——意大利乡村,从早期农村改革到后乡村视角

2019-11-26安娜艾琳德尔摩纳哥AnnaIreneDelMonaco

安娜·艾琳·德尔·摩纳哥/Anna Irene Del Monaco

周政旭 译/Translated by ZHOU Zhengxu

1 前言

农业地域是一种“人居环境”,它出现在城市肌理之前(暂时地)和之外(在地理和功能上)。城市肌理由乡村地区产生,依赖其存在,并与之融为一体。简·雅各布斯在其成功的处女作 《美国大城市的生与死》之后,在《城市经济》[1]中总结到,乡村经济,包括农业劳动力,直接建立在城市经济和城市劳动力之上。

今天,在意大利和全球其他若干区域,城乡一体化不再仅仅是与农产品生产和城市财富密切相关的功能联系和空间互补。实际上,在数十年内,意大利南部的乡村地区已经失去了传统职业和功能性身份:大量的土地已被弃耕,许多在南方基金1)支持下建立和扩张的农场和乡村建筑已经转型为休闲胜地、昂贵或大量的住宿设施。尽管意大利北部的帕达纳城市群或波河河谷仍然属于高效率地区,该区域具有可以回溯到帕拉迪奥时代的水力填海和河流治理工程,现在正转向单一文化境地,并面对着日益增加的分散型都市化和乡村旅游带来的压力。地理学者认为,波河流域是意大利最富有的地区,而且是人口最稠密的区域(尽管威尼托在19 世纪晚期曾经是最贫穷的地区),而且是意大利唯一与中国的珠江三角洲地区十分类似的大尺度城市化区域[2]。

此外,《意大利宪法》批准的景观主题的重要性也随着《2000 年欧洲景观公约》以及立法和各部门政策的演变而在政治上有所增强,各类文件包括《2000 年意大利文化遗产和景观法典》《国家农村发展计划2007/2013》,以及2014-2020 年的农业政策的战略目标。实际上,在北方和南方地区,农业景观的物理改变也会导致最现代化技术的使用(例如温室种植产业等)。

然而,正如意大利目前渴望以原产地农产品、乡村旅游和休闲开发加强吸引外国旅游者和投资人所展示的,现在的城乡关系似乎变成了神话和幻象。下文包括意大利乡村地区通过在20 世纪修改城乡之间的边界和限制(物理和概念上)而实现的主要相关创新(政策和建筑设计),也证明当前在生产和人口恢复战略方面缺乏一种综合性全国计划来恢复农业区域,因为主要的转型和投资普遍是由工人和私人企业或倡议推动的。

为了更好地理解意大利当代乡村生活状况,从历史上追寻不断演进的空间格局将是一件有趣的事。这种空间格局证明了乡村生活理念已应用于城市内外,它取决于持续的已规划或未规划的公共或私人金融机制:如战后乡村聚落的马尔泰拉、公共住房计划的蒂布蒂诺、大众旅游投资的奥斯图尼瓦尔图尔村,以及今天的私人旅游倡议。所有对这些事实、图纸及设计项目的筛选和组织,将被运用于不同文化背景和思潮(理性主义、乡土主义、新现实主义、如画风格等)的讨论中。

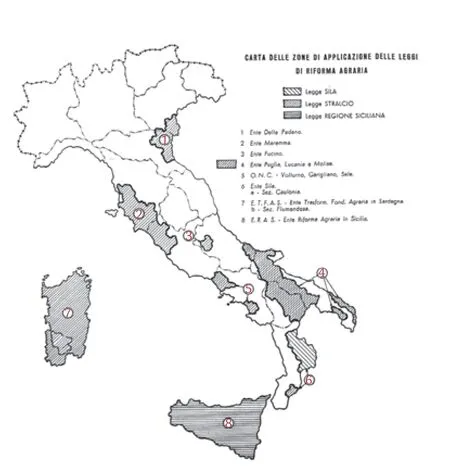

1 1950年土地改革计划/Agrarian reform chart 1950(图片来源/ Sources: BASIRICÒ T. Progetti e costruzioni per la colonizzazione agraria del '900. Italia Spagna Portogallo, Aracne 2018.)

2 相关文献

尽管各种讨论很少共同陈述或具有统一方式,但大致按10 年划分,以形成一个关于意大利乡村与建筑设计进步的综合性论述。例如,专门研究意大利法西斯主义时期的建筑历史学家,如斯皮罗·科斯托夫[3],乔治·丘奇[4],黛安·吉拉尔多[5], 或者亚里士多德·卡利斯特[6],倾向于在理性主义建筑框架下探讨庞廷的土地整理及其以乡村为基础的城市。其他研究城市规划、公共住房和战后大规模的城市移民的学者如彼得·罗[7]和宝拉·迪·比亚吉奥[8]撰写了如INAcasa 计划(一项政府资助的可负担住宅计划)的有关政策和类型先例。或者,学者们提出关于建筑和技术原始形式的理念,以米开朗基罗·萨巴蒂诺[9]为代表的学者通过研究《卡萨贝拉》创始人朱塞佩· 帕加诺的作品及其遗产探讨了地方和官方建筑之间的联系。或者,如同法比奥·曼戈尼[10]、杰玛·贝利及玛丽亚·格拉齐亚·坦佩雷利在其书中有趣地描述的那样,研究19 世纪和20 世纪意大利的旅游聚落景观的历史。

其次,对于意大利南部的问题,在开发计划和政策方面一直有大量的研究,正如萨比诺·卡塞塞写道:“自由时代最重要的知识分子和政治家已经考虑过南北划分这一‘最卓越的国家问题’。在经历长达20年的法西斯主义统治期间,这一问题被从公众讨论中清除,直到意大利共和国时期,该问题重新回到多数政党的政治议程上。土地改革,南部开发基金拉近了这个国家的南北两部分之间的距离”[11]。今天,由于经济形势,也因为结构性经济条件导致的南北意大利乡村地区的巨大差异,两部分之间的分野正日益成为一个重大的全国性问题。

1 Premise

Agricultural territory is a kind of "human settlement" that emerged before (temporally) and outside (topologically and functionally) the urban texture. It is generated by, dependent on, and integrated with it. The revelatory lessons by Jane Jacobs gathered in the book The Economy of Cities[1]- built on the success of her debut book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities - points out that rural economies, including agricultural labour, are directly built upon city economy and city labour.

Today in Italy and in several other regions globally, the integration between the rural and the urban no longer corresponds to just the close functional connection and spatial complementarity related to production of agricultural goods and city wealth. Indeed, within a few decades, the agricultural areas of the Mezzogiorno (Southern Italian regions) have been losing their traditional vocation and functional identity: many lands have been left uncultivated, many farms and rural buildings built and expanded thanks to the incentives of the Cassa del Mezzogiorno1), have been transformed into resorts, expensive or mass accommodation facilities. Whereas the Megalopoli Padana or Po Valley (Northern Italian regions), still highly productive, due also to the historical hydraulic reclamation and river regulation works - dating back to Palladio's time - is turning to monocultural conditions and dealing with the increasing pressure of scattered urbanisation and rural tourism. The Po Valley is considered by geographers the richest and most densely populated Italian area (although Veneto was the poorest during the late Nineteen century), and is the only Italian large-scale urbanisation phenomena most closely comparable to the Chinese Pearl River Delta[2].

Furthermore the importance of the theme of landscape, ratified by the Costituzione Italiana (Italian Constitution), grew politically also with the European Landscape Convention 2000, as well as the evolution of the legislative framework and various sectors of policies: Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio (Italian Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code) 2000, the strategic objective in the Piano Nazionale di Sviluppo Rurale (National Rural Development Plan) 2007/2013 (PSN) and in agricultural policies 2014-2020. Indeed, today both in Northern and Southern areas the physical alteration of the agricultural landscape is also the result of the use of the most modern technologies (such as the greenhouses crops industry, etc.).

Nevertheless, the current relationship between the urban and the rural domain seems to have become myth and mirage, as demonstrated by the current yearning in Italy for agricultural products at kilometre zero and the most recent private investment to enhance touristic and leisure development in the countryside attracting particularly foreign tourists and investors. The following paragraphs include the major relevant innovations (policies and architectural design) implemented in the Italian countryside through the last century modifying the boundaries and the limits (physical and conceptual) between urban and rural areas, demonstrating also the contemporary lack of a comprehensive national plan to regenerate the agricultural areas in terms of production and repopulation strategies, as the main transformation and investments are prevalently driven by individual and private entrepreneurship or initiative.

For a better understanding of the situation of life in contemporary Italian countryside it would be interesting to trace historically the dynamics of a changing spatial pattern demonstrating that the implementation of the idea of rural life has been built in and out of the city depending on the on-going planned or unplanned, public or private financial mechanism: the post war rural settlements (La Martella), public housing programmes (Tiburtino) and the mass tourism investments (Ostuni Valtur Village), the private tourism initiatives of today. All these traces will select and reorganise facts, figures and design projects usually discussed in different cultural contexts and scholars' specialisations (rationalism, vernacular, neo-realism, picturesque, etc…).

2 Precedents in the literature

The topics discussed below and subdivided by decades are rarely presented jointly or reconnected unitedly for a comprehensive discourse in which the Italian Countryside is directly related to the advancement and innovation in architectural design. For instance, historians of architecture specialised in the Italian fascist period, like Spiro Kostof[3], Giorgio Ciucci[4], Diane Ghirardo[5], or Aristotle Kallis[6]tend to discuss land reclamation of the Pontine land and its rural foundation cities within the framework of the topic of "rationalist architecture". Other scholars researching urban planning, public housing and post war mass urban immigration, such as Peter Rowe[7]and Paola Di Biagio[8], wrote about policies as INA-casa Plan (a government-sponsored affordable housing programme) and typological precedents. Or else, on the idea of the primitive form of construction and techniques, the connection between the vernacular and the official architecture like Michelangelo Sabatino[9]investigates with special reference on the work of Giuseppe Pagano, founder of Casabella magazine, and its legacy. Or on the history of the landscape of tourist settlements in Italy in ninetieth and twentieth century as interestingly described in their book by Fabio Mangone[10], Gemma Belli and Maria Grazia Tampieri.

Then, there is a consistent number of studies addressing the issue of Mezzogiorno, the southern Italy microregion, in terms of development programmes and policies, a relevant issue on which, as Sabino Cassese[11]writes "the most important intellectuals and politicians of the liberal age have considered the North-South divide 'the national question par excellence'. After the twenty years of fascism, which erased the problem from public debate, in the republican Italy the question returned to the political agenda of mass parties. The agrarian reform, the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno (Svimez) brought the two parts of the country closer together". Today the divide among the two parts, because of the economic situation, is increasingly growing as a major national problem also because the northern and the southern Italian countryside are deeply different also due to their structural economic conditions.

3 Land reclamation during Fascism (1920s-1940s)

The reclamation of rural areas begun before the Unity of Italy (1861) and continued during fascism as Emilio Sereni stated well in his books Capitalism in the Countryside, 1860-1960[12]and History of the Italian Landscape[13]. The land reclamation interventions recovered marshlands located in Pontine plain in Latium, Sardinia, Apulia, Campania (Fig.1). Many of these places in the oldest time were regular stops during the Gran Tour and where it was possible to contract malaria or other diseases, as at the nearby the Paestum Temples.

In 1937 Mussolini considered the "ruralisation of Italy" as an antidote for the progressive sterility of the population seen as "a consequence to the industrial revolution's urbanisation [...] thus became the reference points of urban planning as a political-technical discipline useful in the implementation of programmes of 'totalitarian national farm'."[14]The results of this new national agricultural policy (the launching of the Battle of the grain) revealed successful measures after only six years.

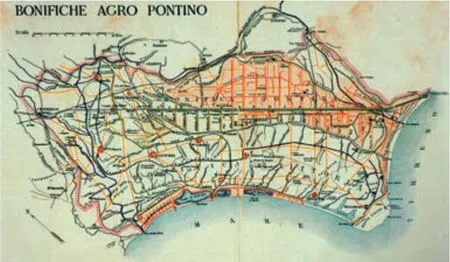

The "disurbamento" (disurbanism) theory, elaborated by the architects during the Fascist Regimen, Gustavo Giovannoni in particular, - considered among the most original contribution of Italian culture in that period - was first of all a territorial plan which would finally make available, as Alberto Calza-Bini wrote "a tool of harmonious discipline, with which the aims the Regime has set itself may be achieved: removal of unemployed from the major city centres, the equitable distribution of productive work throughout the national territory, the enhancement and strengthening of natural land resources."[15]Then the theory of "disurbanism" was related to the establishment of new centres, especially in areas of total land reclamation: "although it applies to a regressive scope such as that of 'totalitarian ruralisation', it became an experimental terrain for some of the most beautiful achievements of young Italian architects and urban planners with newly built new towns with vernacular, neorealism, rationalist features. We have always spoken of these new centres as the "new cities". But Luigi Piccinato, presenting the plan of Sabaudia in 1934, calls them "non-city", as a tribute to the theories of the "disurbanism". "Non-city" in as much as mere centres of services for the agricultural reclamation area"[14](Fig.2).

Together with the agrarian one other social reforms were issued: in 1947 the Legge Fanfani (Inacasa Plan) had the aim of solving the public/affordable housing issue together with the scourge of post-war unemployment. The Ina-casa Plan was partially funded by the Marshall Plan - "European Recovery Programme". After 14 years it gave work to 600,000 workers to build 350,000 dwellings (2800 dwellings per week). In this case too, the youngest and talented architects had the opportunity to prove their qualities as in Quartiere Tiburtino (1949-1954) authored largely by Mario Ridolfi and Ludovico Quaroni and others (Fig.3). On a 9-hectare sloping site in the Rome's eastern periphery, Tiburtino was composed of 771 dwelling units for 4000 inhabitants. The target population was lower-income immigrants to Rome from rural areas in neighbouring provinces and from southern Italy. The design proposal was based on the development of a "shape grammar" based mainly on the studies of Ridolfi establishing some specific elements of the project "sympathetic to the informal and ad hoc configurations and architectural inventions to be found in countryside villages and towns familiar to the new immigrants […]. Overall and in combination with garden terraces alongside of small, well vegetated, and paved plaza as well as interstitial spaces, a picturesque vernacular developed with the look of a small Italian town amid otherwise modern materials and construction techniques"[7]39.

2 庞廷平原规划(1930年代后期),国家行动/Pontine Landfield Plan (late 1930s), Opera Nazionale Combattenti (图片来源/Sources: 参考文献/Ref[14];又见/See also: Onc, L' Agro Pontino. Anno XVIII, Roma. )

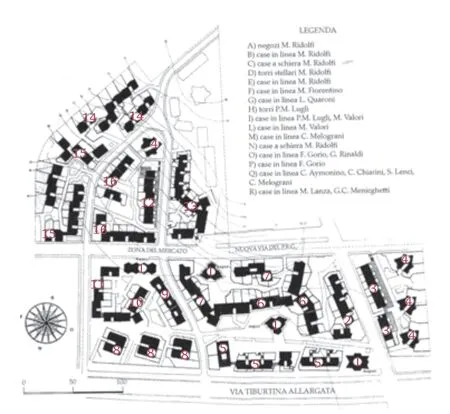

3 Tiburtino住宅区,由马里奥·里多尔菲和鲁多维科·夸罗尼 等人设计/Tiburtino Neighborhood by L. Quaroni, M. Ridolfi, et others, 1950-1954(图片来源/Sources: ROSSI P O. Guida all' architettura modena 1909-2000. Laterza, 2003: 173.)

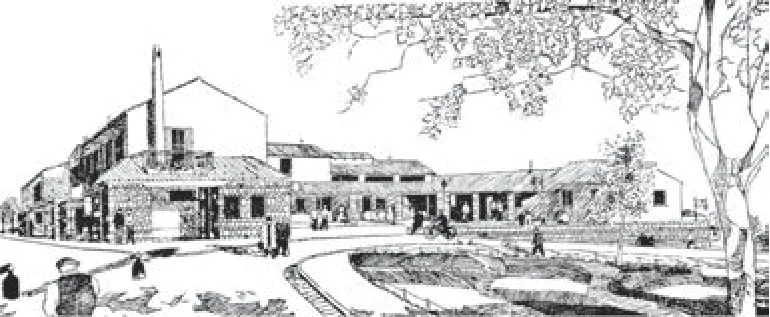

4 拉马尔泰拉,马泰拉/La Martella Village, Matera, 1952(图片 来源/Sources: TAFURI M. Ludovico Quaroni e lo sviluppo dell' architettura moderna in Italia. Edizioni di Comunità, 1964.)

3 法西斯统治期间的土地整理(1920-1940年代)

乡村地区的整理始于意大利统一之前(1861 年),并在法西斯统治期间继续推进,这一点在埃米利奥·塞雷尼的作品《乡村资本主义,1860-1960》[12]和《意大利景观的历史》[13]中有清晰的介绍。土地整理干预措施恢复了位于拉丁、撒丁岛、阿普利亚、坎帕尼亚的庞廷平原上的沼泽地(图1)。在最古老的时代,这些地方的很多地区都是游学之旅的常规站点,在这里如帕埃斯图姆神庙附近可能会感染疟疾或其他疾病。

1937 年,墨索里尼认为,“意大利的乡村化是一剂解毒剂,可以缓解日益增长的人口减少症,这被视为‘工业革命的城市化导致的后果’,因此成为对实施‘极权主义国家农场’计划具有政治-技术学科有用的参考要点”[14]。这一新的国家农业政策(“谷物之战”)仅仅在6 年间就已见成效。

法西斯统治时期的建筑师们,尤其是古斯塔夫·乔万尼,所阐述的“反城市理论”,被认为是该时期意大利文化最具原创性的贡献之一。该理论首先是一项国土空间计划,正如阿尔韦托·卡尔扎-比尼所描述的:“一种和谐管制的工具,政权可以通过它来实现自己的目的:将失业者从主要城市中心迁出,在全国范围内公平分配生产性工作,增加及加强自然土地资源”[15]。当时,这种“反城市主义”理论与建立新中心有关,尤其是在整个土地整理区域:“尽管它适用于退化的范围,例如‘集权主义乡村化’,对于一些年轻的意大利建筑师和城市规划者而言,它已经成为一个试验性的地方,拥有新建成的新城镇,它们具有本土、新现实主义和理性主义的特征。我们一直把这些新中心称为‘新城市’。但是路易吉·皮奇纳托在1934 年提出了萨博迪亚计划,将它们称为‘非城市’,是对‘反城市主义’理论的致敬。 ‘非城市’不仅仅是农业垦区的服务中心”[14](图2) 。

除了土地改革之外,还有其他社会改革被发起了:1947 年,莱格·范凡尼INA-casa 计划的目标是解决公共住房/可负担住宅问题及战后失业问题。INA-casa 计划由欧洲复兴的经济援助计划“马歇尔计划”提供部分资助。经过14 年的努力,该计划为60 万工人提供工作机会,建造了35 万套住房(每周建造2800 套住房)。同样在这种情况下,就像马里奥·里多尔菲和鲁多维科·夸罗尼等人所作的Tiburtino 住宅区(1949-1954)中所展现的那样,最年轻的和最富有才华的建筑师们利用这个机会证明了它们的卓越品质(图3)。Tiburtino 住宅区位于罗马东部边缘一个9hm2的山坡,这里建造了771 套居住单元,可容纳4000 名居民。这些住房的目标人群是来自邻近省份农村地区和意大利南部的低收入移民。该设计方案基于“形状文法”理论的发展,主要基于对里多尔菲的研究,确立了项目的一些特定元素:“与新移民所熟悉的农村村庄和城镇中常见的非正式自发配置与建筑发明相呼应……在总体上进行规划,并与花园露台、绿化良好的小广场及空隙空间相结合,运用现代材料和建筑技巧,形成了独特的本土景观,呈现出一个意大利小镇的风貌”[7]39。

时至今日,1930 年代的研究在概念上仍然未被超越,仍然具有参考价值,例如由瓜尔尼罗·丹尼尔和朱塞佩·帕加诺于1933 年出版的《意大利乡村建筑》以及达戈贝托·奥丁西于1931 年出版的《乡村建筑》。

4 乡村移民,土地改革(1940-1950年代)

二战后,紧张的气氛席卷了南方农村。大约1/8的意大利人口——4600 万人中至少有600 万人仍然不会读也不会写。文盲是一种社会隐患,尤其是在意大利南部的农村中心区域。根据1951 年的人口普查,文盲的“资格”不再属于那些不会写自己名字的人,而是属于那些不会读书和写字的人。1947 年9 月17日,意大利政府颁布了一项建立公立工人学校的法令,以应对这种紧急情况2)。

阿尔契德·加斯贝利总理领导的政府通过改革实现了多种政治目标。这些政治目标旨在缓解南方乡村地区的社会紧张状况,努力让劳动力继续从事农业生产,并重建一个扎根于农田的社会结构,这一切都和共和国民主制度的命运息息相关。

1950 年,土地改革开始了,范围涉及莫利塞、普利亚、巴斯利卡塔、卡拉布里亚、西西里岛、撒丁岛,以及其他地区的一些省份:波河三角洲、马雷马和富奇诺。超过300hm2的土地被征收,2800 名业主得到补偿,被征收的70 万hm2土地作为农场分配给农民的主要来源。

随着土地改革的推进,一个独立的公共行政机构南方基金成立了,专门负责意大利南部的特殊发展政策3)[11]。受影响的区域包括所有南部地区以及拉齐奥、马尔凯和托斯卡纳大区的一些地区。南方基金的最初拨款达1 万亿意大利里拉,供10 年内使用。它的功能本质上是建造公共工程。在南方基金的行动下,整理工程已经完成,灌溉面积超过50 万hm2。修建了新的水渠,各地都改善了道路状况。

正如学者们所确认的那样,南方基金的作用就像罗斯福所倡导的田纳西州流域管理局一样,是“一个被授予政府权力但拥有私营企业灵活性和主动性的公司”[16]。1950-1960 年的10 年间,南方基金批准了169,202 个项目,金额高达1.4 万亿意大利里拉,其中1029 个项目涉及公共工程部门,374 个项目涉及私营部门。

南方农业基础设施大大改善了生产系统,产量翻了一番。在许多垦区,例如梅塔庞蒂诺的垦区,人口增长了4 倍,失业现象被根除。这些转型为新的社会团体和新的统治阶级开辟了道路。这些投资是1960年代大众旅游发展的基础,特别是在沿海地区,而且仍然是当代豪华旅游和大众旅游的基础。

在1950 年代,马泰拉——位于意大利南部巴斯利卡塔的一座拥有6 万居民的城市,因被选为2019年欧洲文化之都而闻名于世——曾经是一个试验场,尤其是建筑新现实主义的试验场。

1943 年,美国人对马泰拉的兴趣日益增加,当时美国军队途经附近的领土登上半岛,看到仍然住在洞穴民居的人们。在土地改革和《马泰拉特别法》的框架内,农村工人从洞穴民居搬迁到7 个新建的社区,如拉马尔泰拉和斯宾比安克。这场干预行动由马泰拉城市和农业研究委员会资助,并由联合国救济和重建署无家可归者援助委员会(UNRRA-CASAS)及国家规划研究所(INU)推动,在INU 所长阿德里亚诺·奥利维蒂和美国阿肯色大学德裔社会学家弗雷德里克·弗里德曼的倡议下,第一次关于马泰拉的系统认知调查的目标是创建新的“社区”,在这些社区中,教育运动和人类重组受到青睐。1949 年,奥利维蒂的私人朋友弗里德曼抵达马泰拉,他的研究也以各种文献为基础,如卡洛·列维的著作《基督停留在埃博利》(1945)。弗里德曼认为马泰拉是一个农民世界的典型地区。他发现“……农民生活的客观条件和其反应的高尚之间形成鲜明对比。这种对比教会了来访者……这种穷困不仅仅是物质条件的状态……这是一种生活方式,是一种生活哲学……”。

Studies that still remain valid references, as of today not conceptually surpassed, were produced during the thirties as The Italian Rural Architecture by Guarniero Daniel and Giuseppe Pagano - Casabella editor in 1933 - and the manual published by Dagoberto Ortensi in 1931 as Rural Buildings.

4 Migration from the countryside, the Agrarian Reform (1940s-1950s)

Immediately after the Second World War a tense climate swept the southern countryside. About one-eighth of the Italian population - at least 6 million citizens out of 46 million - could still neither read nor write. Illiteracy was a social scourge especially in the rural centres of Southern Italy. For the general census of 1951, the "qualification" of illiterate was no longer attributed to those who could not write their name, but to those who could not read and write. The Italian government responded to this emergency by issuing a decree-law instituting public workers schools on September 17, 19472).

The political objectives of the government lead by Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi through the reform aimed to appease social tensions in the southern countryside, trying to keep the workforce in agricultural activities and to rebuild a social fabric anchored to the farmlands, involved in the fate of the republican democratic system.

In 1950 the agrarian reform was launched concerning Molise, Puglia, Basilicata, Calabria, Sicily, Sardinia and some provinces of other regions: the Po Delta, the Maremma and the Fucino. Properties exceeding 300 hectares are expropriated 2800 owners are indemnified. The 700 thousand expropriated hectares constituted the majority of the lands assigned as farms to the peasants.

With the agrarian reform, Cassa del Mezzogiorno3)[11]was established, an independent body of the Public Administration dedicated to special development policy for the Southern Italy. The territory included in its sphere of influence all the southern regions and some areas of the regions of Lazio, Marche and Tuscany. The initial allocation of the Cassa amounts to one trillion, to be used over a period of ten years. Its function was essentially to build public works. With the actions of the Cassa, reclamation was completed and irrigation extended to over 500 thousand hectares. New aqueducts were built and roadways were improved everywhere.

As scholars affirm Cassa del Mezzogiorno was intended like the Tennessee Valley Authority promoted by Franklin Delano Roosevelt "a corporation clothed with the power of Government but possessed of the flexibility and initiative of a private enterprise"[16]. Over a decade, from 1950 to 1960, the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno approved 169,202 projects, for an amount of 1403 billion Italian Liras, of which 1029 related to projects in the public works sector and 374 the private sector.

The infrastructure of southern agriculture greatly improved the production system, doubling its output. In many reclamation areas, such as that of the Metapontino, the population grows even fourfold and unemployment was eradicated. These transformations opened the way for new social groups and new ruling classes. These investments were at the basis of the mass tourist development during the Sixties, especially in the coastal areas, and are still the basis for the contemporary luxury and low-cost tourism.

During fifties, Matera - a city of 60 thousand inhabitants in Basilicata internationally renowned as it was selected as the 2019 European Capital of Culture - was already an experimental field especially for architectural Neorealism.

The interest of the Americans in Matera grew in 1943 when the American Army was going up the peninsula passing by territories nearby and saw people who still lived in the caves (Sassi). In the framework of the Agrarian Reform and of the Special Law for Matera the rural workers were relocated from Sassi to seven newly built neighbourhoods such as La Martella and Spine Bianche. The intervention was funded by The Commission for the study of the city and the Agro of Matera and was promoted by the UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) - CASAS (Homeless Assistance Committee) and the INU (National Planning Institute), on the initiative of Adriano Olivetti, president of INU, and Frederic Friedmann, a German sociologist professor at the University of Arkansas, USA. The goal of this first systematic cognitive survey on Matera was to create new "communities", in which pedagogical moments and human reorganization were favoured. Friedmann, a personal friend of Olivetti, arrived in Matera in 1949 grounding his research also on documents like Carlo Levi's book Christ stopped at Eboli (1945). Friedmann recognised Matera as an exemplary place, a model of the peasant's world. He discovers "... the striking contrast between the objective conditions of the peasant's life and the nobility of his reactions. This contrast teaches the visitor ... that misery is more than a state of material condition ... it is a way of life, a philosophy ..." (Fig.4).

La Martella is one of the most relevant completed rural villages designed (1952-1954) by Ludovico Quaroni with Federico Gorio, Michele Valori, Piero Maria Lugli, Luigi Agati. Spine Bianche is a residential neighbourhood designed by Aldo Aymonino and others implemented together with Giancarlo De Carlo and Mario Fiorentino. According to Manfredo Tafuri, it "represents an attempt to rationalisation of populist etymologies. According to Vittorio Gregotti, with Spine Bianche it is implemented a dialogue between the tradition of Milanese rationalism and the research, typical of the Aymonino generation, of a critical realism able to face, on the concreteness of the Italian context, the best traditions of modern design. The project expresses the transition to significant modification, as an awareness of being in history without depending on it."[17]Besides Southern Italy other regions were also involved in the reclamation processes and other agencies were founded like Ente Maremma (Southern Tuscany), and the already mentioned Pontine plain.

5 The failure of the Agrarian Reform (1950s-1960s): the Mediterranean myth and the vernacular architecture

The Agrarian Reform fails, in the transition between the years Fifties and Sixties due to the industrial development of Northern Italy and Central Europe and with the consequent migration of the agrarian masses (villages of the abandoned Reformation especially in Calabria and Sicily). However, the culture of vernacular architecture as an alternative language to modernism will continue to be practiced and studied by architects and scholars.

Ludovico Quaroni elaborated studies for cities in Apulia and Basilicata, in particular A Study for the Coordination of Reclamation Area (1956) and Three Conferences on the Urban Planning and the Southern Italian Buildings later published in the book The Physical City of 1981[18]. However, this will not be just an Italian cultural phenomenon: one of the most internationally relevant contribute during those years is Architecture without Architects of Bernard Rudofsky[19]published in 1964. He also designed a remarkable project, Villa Oro, in Naples with Luigi Cosenza (Fig.5).

The mid-sixties, the years of the economic boom, are also the years of the "cementification of the coasts", as the two issues of Casabella of 1964 dedicated to the Italian coasts denounce.

All the architectural experiments and typological models developed for almost three decades (from 1930s to 1960s) represent an important ground of knowledges and references for the modern tourist settlements built beginning in 1960s in Italy - directly and indirectly financed by northern industrial groups and state companies - linguistically grounded on the studies and experiences of the period of neo-realism and of the major agrarian reforms. A significant set of examples are the three Tourist Villages[20]built by Valtur4)in southern Italy, from 1966 to 1972, Ostuni in Apulia, Isola Capo Rizzuto (Calabria), Brucoli (Sicilia), designed by Lucio Barbera, Luisa Anversa, Gabriele Belardelli (Fig.6), published by Bruno Zevi in his magazine L'Architettura. Cronache e storia during the early Seventies and winning National prize (IN/ARCH). They may be considered a relevant typological alternative of tourist residences experimenting "the compact settlements instead of the isolated villa to protect the integrity of the Mediterranean landscape" as Zevi argued in his critical editorial text: "The greatest merit [of these villages] - he continues - seems to have burned both the myths of spontaneous architecture, and the international schemes detached from the history of those regions. But having considered the means of establishing the new environment, perhaps traceable in the positive experience of the Roman school, in particular Ridolfi and in the ways of aggregating volumes that refer to the English residential experiences such as those of Denys Lasdun or James Gowan". It is the beginning of a phase in which countryside and seaside in Italy become privileged fields of mass tourism and of developers' interventions (especially the seaside coastal areas). According to Istat, the national census bureau in 1959 only 13% of the population went on vacation while in 1985 it rose to 59%. The highly exclusive beach resorts of the earliest seaside tourism were built in Rimini (1843) and Venice (1857) while after 1930 they started becoming popular and rapidly multiplied.

5 奥罗别墅,那不勒斯,由路易吉·科森扎和伯纳德·鲁多夫斯基 设计/Villa Oro, Naples, by Luigi Cosenza and Bernard Rudofsky, 1934-1937(图片来源/Sources: https://www.archiportale.com)

6 瓦尔图尔,奥斯图尼,由由卢西奥·巴贝拉、路易莎·安弗洛 斯、加布里埃尔·贝拉德利设计/Villaggio Valtur, Ostuni, by Lucio Barbera, Luisa Anversa, Gabriele Belardelli, Vieri Quilici, Claudio Maroni, 1970(图片来源/Sources: 参考文献/Ref[20])

拉马尔泰拉(图4)是由鲁多维科·夸罗尼、费德里科·戈里奥、米歇尔·瓦洛里、皮耶罗·玛丽亚·陆格利及路易吉·阿格缇设计(1952-1954)的最具相关性的已建成村庄之一。斯宾比安克是奥尔多·艾莫尼诺和其他人设计的住宅小区,与吉安卡洛·德·卡洛、马里奥·佛罗伦萨共同实施。根据曼弗雷多·塔夫里的说法,它“代表了一种平民主义词源学的合理化尝试。维托里奥·格雷戈蒂认为,通过斯宾比安克项目,在米兰理性主义传统与艾莫尼诺一代典型的批判现实主义研究之间实现了一场对话,而批判现实主义在意大利语境的具体层面,是现代设计的最佳传统。这个项目表达了向重大修正的转变,是一种不依赖于历史却存在于历史之中的意识”[17]。除了意大利南部之外,其他地区也参与了土地整理过程,而且还建立了其他机构,如恩德马雷马(托斯卡纳区南部)和上文已提到的庞廷平原。

5 土地改革的失败(1950-1960年代)地中海神话和乡土建筑

在1950、1960 年代的过渡时期,由于意大利北部和中欧的工业发展,以及随之而来的农业人口迁移,土地改革遭遇了失败。然而,建筑师和学者们继续研究和实践乡土建筑文化,以其作为现代主义的替代语言。

鲁多维科·夸罗尼对阿普利亚和巴斯利卡塔的城市进行了详细的研究,尤其是在其于1956 年出版的《整理区协调研究》和在《3 次关于城市规划和南部意大利建筑的会议》中对这些城市有详细论述,后来1981 年他将这些会议论述集结出版了《体形城市》一书[18]。然而,这不仅仅是一种意大利文化现象:在那些年中,最具国际相关性的贡献之一是伯纳德·鲁多夫斯基[19]于1964 年出版的《没有建筑师的建筑》。他还在那不勒斯和路易吉·科森扎一起设计了一个著名的项目——奥罗别墅(图5)。

1960 年代中期是经济繁荣的年代,正如1964年专门讨论意大利海岸的两期《卡萨贝拉》所谴责的那样,这段时期也是“海岸水泥化”的年代。

在近30 年间(1930-1960 年代)发展起来的所有建筑实验和类型学模型,是意大利1960 年代开始建设的现代旅游区的一种重要的知识基础。这些旅游区直接和间接由北方工业集团和国有公司提供资助——在语言上以新现实主义时期和重大农业改革时期的研究和经验为基础。一组重要的例子是由瓦尔图尔4)于1966-1972 年间在意大利南部建造的3 个旅游度假村[20]:阿普利亚的奥斯特尼、卡拉布里亚的伊索拉卡波里祖托、西西里岛的布鲁科利,这些度假村由卢西奥·巴贝拉、路易莎·安弗洛斯、加布里埃尔·贝拉德利设计(图6)。由布鲁诺·泽维于1970 年代初在其杂志L'Architettura. Cronache e storia 中发表,并荣获国家级大奖(IN/ARCH)。它们被认为是旅游住宅试验的一种替代形态,这种试验是泽维在其评论文章中提出的“紧凑型居住区,而非孤立别墅,以保护地中海景观的完整性”:“(这些村庄)最大的优点——他继续说道——似乎消灭了自发建筑的神话,也消灭了脱离这些地区历史的国际计划。但考察了建立新环境的各种方式,也许在罗马学派的积极经验中可以寻觅踪迹,尤其是在里多尔菲身上,以及参考英国居住经验的各种方式中,如丹尼斯·拉斯顿或詹姆斯·高恩的经验。”这是意大利的乡村和海滨成为大众旅游和开发商特权领域(尤其是海滨沿岸地区)的开始阶段。根据意大利统计局的记录,1959 年,国家人口普查局统计到只有13%的人口去度假,到了1985 年度假人口比例上升至59%。最早的海滨旅游胜地建于里米尼(1843)和威尼斯(1857),而在1930 年后,它们开始变得十分流行并迅速成倍增加。

从1970 年代开始,农业用地政策被放弃。人们假定现代农业必须考虑少数拥有尖端技术和工艺的熟练工人——这占很低的人口比例(见美国、德国等国的农业人口数据),这种看法也许是正确的。

在这一框架内,学者们将城市-区域关系的愿景视为一种人类学-建筑学研究领域,正如维托里奥·格里高蒂(时任《卡萨贝拉》编辑) 于1985 年出版的著名论文《区域与建筑》中所宣称的那样,作为一个理论和结构研究领域,其中整个区域都在努力实现生活质量和功能的对等。这些意大利建筑文化的方法出现在著名的杂志《卡萨贝拉》——格雷戈蒂编辑的“建筑的区域”中,或者鲁多维科·夸罗尼讲授的设计工作室课程中。鲁多维科致力于罗马-佛罗伦萨和罗马-那不勒斯之间的激进的乌托邦原型连续体城市研究[21],尤其考虑到基础设施的漫长建造过程,1968 年,由乔治·拉夫洛领导的经济部启动了一项全国方案——“1980 年代计划”[22](图7),围绕该计划,全国开展了一系列讨论,形成了一些基本原则。推广国家基础设施发展的先进理念和基于“综合发展方法”景观理念的简单概念化,但由于政治经济中采用了压倒一切的文化方法,该计划失败了。今天,尽管一些观察家告诉我们,仅有旅游业是不够的,而几十年来农业的发展一直不充分, 除了农业生产发生深刻变化之外,意大利农村越来越多地被用于旅游和娱乐。

6 今天的意大利乡村工业

意大利南部的几个农业区——可以被视为人类景观和自古以来就被改造过的人工产物——如今正在失去其主要的传统功能。近年来,许多土地被荒废,取而代之的是直接的公共支付和奖励。近几十年来,在此季节性就业的工人大部分是移民。这些农场建筑(农场、农舍、商店)中的许多建筑都是在南方基金的激励下建造和扩建的,现已转变为农场、度假村、独家和低成本的住宿设施。这一现象体现了许多美丽的意大利后乡村地区的功能变化。在意大利,我们现在正在失去农业。作为一种普遍性实践,这种情况明确证实了内阁会议主席-青年和国家公务员事务部的倡议,它于2016 年10 月建立了农业公务员制度。

一方面,尽管很少,但仍有关于初创公司致力于促进农业生物多样性和新的社会化农场成功的案例;另一方面,有许多关于农民的故事证实了意大利农业结构性变化的原因:其中有一位计算机工程师辞职后建立了一座农场,他以有机的方式种植一种玉米,并在网上进行销售。此外,年轻一代对在农村工作、投资和生活也越来越感兴趣,工作包括葡萄园生产、特殊稀有品种或被弃品种的栽培、住宿加早餐型旅馆或度假村,投资自己的家庭资金或获得公共奖励以更新旧的和被放弃的农村建筑。《金融时报》[23]最近发表的一篇文章讲述了一个前雷曼兄弟公司的白领逃离城市,回到农村生活的故事(生产马苏里拉奶酪和其他奶酪)。文章中还有意大利农业联合会青年农民协会主席的报告:“现在人们认为这是一份不错的工作,且伴以良好的生活方式……毕业生热衷于投资旅游业和农业。”

From the Seventies onward, the abandonment of policies for agrarian spaces followed. It is assumed, perhaps rightly, that modern agriculture must count a small number of skilled workers with cutting-edge technologies and processes - a very low percentage of population (see data on the agricultural population in the USA, Germany, etc.).

In this framework the vision of the relation between city-territory was conceived by scholars as an anthropological-architectural research field, as claimed by Vittorio Gregotti in his well-known essay Territory and Architecture, published in 1985 when he was editor of Casabella, as a theoretical and structural research field in which the whole territory strives for the equivalence of the quality of life and functions. These approaches to Italian architectural culture is presented in a well-known Casabella issue The Territories of Architecture edited by Gregotti, or in the design studio courses taught by Ludovico Quaroni, working on the radical proto-utopian Continuum City[21]between Rome-Florence and Rome-Naples and especially considering the lengthy processes of the infrastructures, some fundamental foreseen in Italy since the national debate around the "Progetto '80"[22](Fig. 7) a national programme started in 1968 by the Ministry of Economy directed by Giorgio Ruffolo promoting an advanced idea of infrastructural development of the country and a primitive conceptualisation of the idea of landscape based on an "integrated development approach" which failed because of the overwhelming cultural approaches in the political economy. Today, besides a deeply transformed agricultural production, Italian countryside is increasingly used for tourism and entertainment although several observers tell us that tourism alone is not enough, as agriculture has not been sufficient for decades.

7 1980年代计划/Progetto 1980s, general scheme(图片来源/ Sources: 参考文献/Ref[22])

6 The Italian Rural Industry Today

Several agricultural areas of the Mezzogiorno - which can be described as an anthropological landscape and man-built artefact modified since ancient times - today are losing their main traditional vocation. Many lands, in recent years, have been left uncultivated in exchange for direct public payments and incentives. The workers, employed seasonally, during the recent decades have been mainly immigrants. Many of the farm buildings (farms, farmhouses, stores), built and expanded with the incentives of the Cassa del Mezzogiorno, have been transformed into farms, resorts, exclusive and low-cost accommodation facilities, thus defining the change of vocation of many beautiful post-rural Italian places. That in Italy we are now losing the agrarian vocation, as a widespread practice, definitively confirms the initiative of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers - the Department of Youth and National Civil Service, which established the option for civil service in agriculture (October 2016).

If on the one hand the success stories of startups - too few succeed - that work on biodiversity in agriculture and promote new social farms, on the other hand there are many stories of farmers who confirm the reasons for the structural crisis of Italian agriculture: among the others there is the example of a computer engineer quit a job to set up a farm producing a forgotten strain of corn, which he grows organically and sells online. Besides, there is also a growing interest among the young generation in working, investing and living in the countryside involved in vineyard production, special rare or abandoned cultivation, running bed and breakfast or resorts, investing their own family money or acquiring public incentives to renew old and abandoned rural buildings. A recent article published on Financial Times[23]narrates the story of a former Lehman Brothers white-collar shunning for rural life (producing buffalo milk to make mozzarella and other cheeses) and the report of the president of Italy's Confagricoltura young farmer's association "It's considered a cool job now with good lifestyle […] Graduates are enthusiastic about investing in tourism and farming".

7 European and Italian tendencies today

Rural Europe is home to more than half of the EU population and covers more than three quarters of the territory. Analysing the Dutch case in a recent interview Rem Koolhaas[24]observes that in an age when we are all obsessed with cities, countryside is the most radical place of transformation, less and less "agricultural" less and less "authentic". The Dutch countryside, like some villages in the Swiss Alps, observes Koolhaas - if on the one hand depopulates, on the other grows and multiplies -, is inhabited provisionally, presents the characteristics of the phenomena of "thinning", increases the area of transformation and the intensity of its exploitation diminishes, since the activities that take place in it have changed: the functions of service have increased and the agricultural ones are greatly reduced or modified: "What we found was a thriving prototype of the nonagricultural countryside - a new genre of land use called 'the intermediate' - a well-manicured place where surface appearances bear almost no relation to what is actually happening on the land and in the buildings" (Fig.8).

Koolhaas's discourse confirms what has been evident since the time of Ambrogio Lorenzetti's fresco in Siena "The Allegory of Good and Bad Government" (1338-1339): although common sense tends to associate agricultural landscape to nature, the countryside is an anthropic and artificial artefact whose authenticity has always been ambiguously interpreted and subjected to the specificity of the economies and policies of the moment and can only be "in tune with our present environmental situation. It can no longer be some sort of idealised reference to a nature inherited from the past, call it "dirty realism" if you wish. For it is precisely this obstinate reference to an idealised nature belonging to another era that has enabled us to perpetrate the worst desecration of nature to this day"[25].

The undefined land called "intermediate" or "periurban" - relating to an area immediately surrounding a city or a town - differs in Europe from city to city. Moreover, it is not always clearly organised by a theoretical scheme as the Five Fingers Plan of Copenhagen elaborated in 1949 by the Dansk Byplanlabouratorium lead by Steen Eiler Rasmussen - or the fringe-belt theories developed by M.G.R. Conzen in the same years for German and English cities. Whatever the regulations or the policies are in Europe there is a growing number of entrepreneurs renovating, transforming, preserving old farmhouses and estates, fifty to three hundred years old, or expanding and refurbishing them into resorts and boutique hotels.

Therefore, there is an interesting growing trend - also a growing business for architects: designing wineries surrounded by vineyards. One of the first winery intended as a contemporary architectural building is the Dominus Winery completed in 1998 in Nappa Valley and designed by Herzog and De Meroun, a building and a landart project using hundreds of gabion baskets filled with local field stone. A few years later, Frank Owen Gehry (Fig. 9) followed in Spain with a project at Rioja accepting the challenge with Marqués de Riscal in 2007, Steven Holl in Austria with Loisium hotel completed in 2005 at Langenlois. Among the most interesting wineries in Italy: La Rocca di Frassinello winery by Renzo Piano (Fig. 10), built in 2007 in the heart of the Maremma in Tuscany, then the Cantina Petra designed in 2003 nearby Livorno by Mario Botta (Fig. 11), the Cantina Antinori opened in Tuscany in 2012 by Studio Archea (Fig. 12), the Cantina Bulgari in San Casciano dei Bagni by Alvisi Kirimoto (Fig. 13) in 2013.

8 库哈斯对荷兰当代乡村的研究/Study on the Dutch contemporary countryside by Koolhaas(图片来源/Sources: 参考文献/Ref[24])

9 里斯卡尔侯爵酒庄酒店,西班牙,2006,弗兰克·盖里设计/ Hotel-Winert Marques de Riscal in Rioja, Spain, 2006 by Frank Owen Gehry

10 斯纳罗葡萄园,托斯卡纳,2007,伦佐·皮亚诺设计/La Rocca di Frassinello, Tuscany, 2007 by Renzo Piano

11 佩特拉酒吧,托斯卡纳,2003,马里奥·博塔设计/Cantina Petra, Tuscany, 2003 by Mario Botta

12 安蒂诺里酒吧,托斯卡纳,2004-2013,阿奇亚工作室设计/ Cantina Antinori, Tuscany, 2004-2013 by Studio Archea

13 宝格丽酒吧,托斯卡纳,2013,拉尔维斯·基里莫托设计/ Cantina Bulgari, Tuscany, 2013 by Alvisi Kirimoto

7 今天欧洲和意大利的趋势

欧洲农村是一半以上欧盟人口的家园,覆盖了超过3/4 的领土。雷姆·库哈斯[24]在最近接受采访中分析了荷兰的情况。他观察到,在一个我们都痴迷于城市的时代,乡村是最激进的变革之地,“农业”越来越少,而“真实”也越来越少。库哈斯发现,荷兰的乡村像瑞士阿尔卑斯山的一些村庄一样——如果说一方面人口在减少,另一方面人口却在增长——因为临时有人居住,这呈现出“稀释”现象的特点,转型的面积增加了,同时开发强度也降低了,因为其中发生的活动产生了变化:服务功能增加了,而农业功能大幅减少或被改变了:“我们曾发现的是非农业乡村的一个繁荣原型——一种被称为‘中间地带’的新的土地利用类型——一个精心整修的地方,这里的表面现象与土地和建筑中实际发生的情况几乎没有关系”(图8)。

库哈斯的论述证实了自安布罗乔·洛伦兹蒂在锡耶纳所绘壁画《好政府和坏政府的寓言》 (1338-1339)时代以来一直显而易见的情况:尽管常识倾向于将农业景观与自然联系起来,但乡村是一个与人类有关的人工产物,其真实性一直被模糊地解释,并受制于当前经济和政策的特殊性,而且只能“与我们当前的环境状况相一致。它不再是对过去传承下来的自然的某种理想,如果你愿意,可以称之为‘肮脏的现实主义’。因为正是这种对属于另一个时代的理想化自然的顽固的参照,允许我们对自然犯下迄今为止最严重的亵渎”[25]。

在欧洲,那些与一个城市或城镇紧邻区域相关的被称为“中间地带”或“城郊”的未定义土地,则因城市而异。此外,它并不总是像1949 年由斯汀·埃拉·拉斯姆森领导的丹麦规划实验室制定的哥本哈根《五指规划》——或者同一时间康赞恩为德国和英国城市研制的边缘带理论那样。无论欧洲有什么样的法规或政策,越来越多的企业家都在翻新、改造、保护那些50 ~300 年前的旧农舍和庄园,或者将它们扩建和翻新成度假村和精品酒店。

因此,有一种有趣的增长趋势——同时也是建筑师们增长的业务:设计由葡萄园环绕的各种葡萄酒厂。其中一个被设计为当代建筑的葡萄酒厂是1998年在纳帕谷建成的多明纳斯葡萄酒厂。它由赫尔佐格与德梅隆设计,是采用数百个装满当地大卵石的石笼建成的一座建筑和一个大地艺术项目。几年后,著名建筑师弗兰克·盖里于2007 年在西班牙的里奥哈地区完成了一个项目:里斯卡尔侯爵酒庄酒店(图9)。而美国当代建筑师斯蒂文·霍尔于2005 年在奥地利的朗根洛伊斯建成了罗仙姆酒店。意大利最有趣的葡萄酒厂包括伦佐·皮亚诺设计的斯奈罗葡萄园(图10),于2007 年建于托斯卡纳区的马雷玛的中心地区,其次是马里奥·博塔于2003 年在利沃诺附近设计的佩特拉酒吧(图11),阿奇亚工作室于2012 年在托斯卡纳开设的安蒂诺里酒吧(图12),以及阿尔维斯·基里莫托于2013 年在圣卡斯基诺代巴格尼开设的宝格丽酒吧(图13)。

当然,基于食品-文化之间的联系,2015 年米兰世博会对农业食品、美食和酒店业带来的积极影响众所周知,而且这些影响与一个真正的、活跃的、有竞争力的行业相一致。测试这些行业对当代建筑的影响将会很有趣——在某种程度上它与乡村生产有关,正如建筑历史学家詹姆斯·阿克曼在其著作《别墅:乡村住宅的形式和意识形态》(1985)中所论述的那样,它证实了社会、经济和政治的变化影响了城乡生活之间那种矛盾的、迷人的和共生的对话。阿克曼的这部著作将各种别墅描述为迄今可设想的最具吸引力的住宅类型之一:“农舍倾向于采用简单的结构,并保存不需要设计师干预的各种古老形式。典型情况下,别墅是建筑师想象力的产物,并强调其现代性。自从古罗马贵族们第一次修复这座别墅以来,别墅的基本规划已经保持了2000 多年未变。这让别墅变得独一无二,而其他的建筑类型——宫殿、宗教场所、工厂——在形式和目的上已经发生了变化”[26]7-10。

但是阿克曼也含蓄地证实了简·雅各布斯在《城市经济》一书中的论点,他断言,“对别墅的理解离不开城市;它的存在不是为了履行自治职能,而是为了给城市价值观和住宿条件提供一种平衡,其经济状况就像一座卫星城市的经济状况……别墅既可以由城市商业和工业产生的货币盈余来建造和支持,或者在城市中心对农业生产的超出自身所需的盈余的需求促进下,由农业维持的人员建造和支持”[26]7-10。

此外,在全球化世界的框架内,酿酒厂的建筑主题事实上反映了阿克曼所探索的价值观,他断言:“在赖特和勒·柯布西耶的作品中,别墅与农场或农舍的区别,如同在西方建筑的所有历史中一样,是意识形态涵义的有计划的应用……乡村,则由于它不可避免地与大自然的内在力量和感官魅力相比较,给我们带来各种富有启发性的答案。”[26]□

Certainly, the positive effects of the post-Milan Expo 2015 on the agro-food and gourmet and hotel industries, based on the food-culture nexus, are well known and correspond to a real, active and competitive industry. It will be interesting to test the impact of these industries - somehow related to the rural production - on contemporary architecture, confirming the contradictory, fascinating and interdependent dialogue between urban and rural life affected by the social, economic and political changes as the architectural historian James Ackerman discusses in his remarkable book The Villa: Form and Ideology of Country Houses (1985) describing villas of all kinds as one of the most attractive types of dwelling ever conceived: "The farmhouse tends to be simple in structure and to conserve ancient forms that do not require the intervention of a designer. The villa is typically the product of an architect's imagination and asserts its modernity. The basic programme of the villa has remained unchanged for more than two thousand years since it was first fixed by the patricians of ancient Rome. This makes the villa unique: other architectural types - the palace, the place of worship, the factory - have changed in form and purpose […]"[26]7-10

But Ackerman, implicitly confirm also the Jane Jacobs's thesis in the book The Economy of Cities when he affirms that "The villa cannot be understood apart from the city; it exists not to fulfil autonomous functions but to provide a counterbalance to urban values and accommodations, and its economic situation is that of a satellite. […] The villa can be built and supported either by monetary surpluses generated by urban commerce and industry or, whom it is sustained by agriculture by the need of urban centres for the surplus it produces beyond its own requirements. […]"[26]7-10

Also, the Winery architectural theme, indeed, in the framework of a globalised world reflect the values explored by Ackeman when he affirms that "what differentiates the vrlla from a farm or a cottage, in the work of F.L. Wright and Le Corbusier as in all the history of Western architecture, is the programmatic application of ideological connotations […] the countryside, with its inevitable comparisons with immanent forces and the sensual charm of the nature, suggests inspired answers."[26]□

注释/Notes

1)南方基金是意大利政府为刺激南部欠发达地区的经济增长和发展而作出的一项公共努力。它成立于1950年,主要目的是建设公共工程和基础设施项目(道路、桥梁、水电和灌溉设施等),提供信贷补贴和税收优惠,以促进投资。尽管它的工作是由连续的、较不集中的机构维持的,但仍于1984年解散。它主要集中在农村地区,许多人说它帮助意大利南部进入了现代世界,尽管有证据表明一些资金由于财务管理不善而被挥霍掉。历史学家丹尼斯·麦克·史密斯在1960年代指出,大约1/3的钱被浪费了。一些钢铁厂等项目承诺但从未建成,许多灌溉项目和水坝也从未按计划完工。/Cassa del Mezzogiorno was a public effort by the government of Italy to stimulate economic growth and development in the less developed Southern Italy (also called the "Mezzogiorno"). It was established in 1950 primarily to construct public works and infrastructure (roads, bridges, hydroelectric and irrigation) projects, and to provide credit subsidies and tax advantages to promote investments. It was dissolved in 1984, although its mandate was maintained by successive, less centralized institutions. It focused mostly on rural areas and many say that it helped Southern Italy to enter the modern world, although there is evidence that some of the funds were squandered due to poor financial management by local southern government. Historian Denis Mack Smith noted, in the 1960s, that about a third of the money was misspent. Steel mills and other projects were promised but never built, and many irrigation projects and dams were never completed as intended. (Wikipedia, March 2019)

2)另一重要贡献来自国家电视台,电视台在1960年代通过电影解决了识字问题。 1960-1968年的一项非常成功的计划是电视节目《永远为时不晚》。/Another important contribution to the cultural progress of the nation came from State television, which in the 1960s tackled the problem of literacy through films. A very successful initiative from 1960 to 1968 was the television programme It's never too late.

3)还可查阅/See also: http://www.sturzo.it.

4)Valtur是一家旅游娱乐私人公司,由Italconsult的总监Raimondo Craveri于1964年成立,由FIAT,Alitalia,Aci,Sara Assicurazioni,Cit和Banque Lambert参与,1974年,意大利政府也通过Insud公司成为该集团的投资者,1976年,Méditerranée俱乐部也加入了该集团。 在随后的几十年中,Valtur聚集了众多公共投资者。/Valtur a private company for tourism and entertainment (Valorizzazione Turistica) founded in 1964 by Raimondo Craveri, director of Italconsult with the financial participation of FIAT, Alitalia, Aci, Sara Assicurazioni, Cit and Banque Lambert. In 1974 also, the Italian Government entered as investor in the group through the company Insud and in 1976 also Club Méditerranée joined. During the following decades Valture gathered public and public investors.

参考文献/References

[1] JACOBS J. The Economy of Cities. Vintage Books, 1970.

[2] BARBERA L, DEL MONACO A I. A Rural-Urban Metamorphosis in China: The Real Great Leap Forward. L'architettura delle città, The Journal of the Scientific Society Ludovico Quaroni, (3-4-5), 2014.

[3] KOSTOF S. The Third Rome. 1970.

[4] CIUCCI G. Gli architetti e il fascismo. Architettura e città 1922-1944. Einaudi, 1989.

[5] GHIRARDO D. Italian Architects and Fascist Politics: An Evaluation of the Rationalist's Role in Regime Building. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 1980: 109-127.

[6] KALLIS A. The Third Rome, 1922-1943: The Making of the Fascist Capital. Palgrave Macmillan,2014.

[7] ROWE P G. Har Ye Kan, Urban Intensities: Contemporary Housing Types and Territories. Birkhäuser, 2014: 39.

[8] BIAGI P. La grande ricostruzione, Il piano Ina-Casa e l'Italia degli anni cinquanta. Donzelli, 2010.

[9] SABATINO M. Pride in Modesty: Modernism Architecture and the Vermacular Tradition in Italy. University of Toronto Press, 2011.

[10] MANGONE F, BELLI G and TAMPIERI M G (eds.). Architettura e Paesaggi della villeggiatura in Italia tra Otto e Novecento. Ricerche Franco Angeli, 2015.

[11] CASSESE S. (ed.) Lezioni sul meridionalismo. Mulino 2016.

[12] SERENI E. Il capitalismo nelle campagne, 1860-1960. Einaudi, 1947.

[13] SERENI E. Storia del paesaggio italiano. Bari, Laterza, 1961.

[14] MUNTONI A. Newly founded Italian Cities of the Thirties. Theories and Technical achievements. L'architettura delle città, The Journal of the Scientific Society Ludovico Quaroni (9), 2016.

[15] BINI A C. Il piano territoriale come strumento della politica fascista del disurbanamento. Urbanistica, gennaiofebbraio, 1941: 3.

[16] ROOSEVELT F D. Message to the Cogress Suggesting the Tennessee Valley Authority. 10 aprile 1933.

[17] LOSASSO M. Quartiere Spine Bianche, Matera (1955-1959): note per una lettura critica. Working Paper, 2010.

[18] QUARONI L. La città fisica (The Physical city). Laterza, 1981.

[19] RUDOFSKY B. Architecture without Architects. John Wiley & Sons, 1964.

[20] Due insediamenti turistici nel Mezzogiorno. Albergovillaggio a Marina di Ostuni, Brindisi. L'Architettura. Cronache e storia(XVI)1970: 6-17.

[21] BARBERA L. The Radical City of Ludovico Quaroni. Gangemi, 2019.

[22] RENZONI C. Il Progetto'80, Un'idea di Paese nell'Italia degli ani Sessanta. Alinea Editrice, 2012.

[23] ROBERTS H. Young Italians shun the city for pull of the land. Financial Times, November 14th 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/baf8c494-72e2-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9.

[24] KOOLHAAS R. Rem Koolhaas: countryside architecture. Icon 2014. http://www.iconeye.com/architecture/features/item/11031-rem-koolhaas-in-the-country.

[25] URSPRUNG P. Nature and Architecture, in Natural Methaphor. An Anthology of Essays on Architecture and Nature, Actar ETH, 2007: 31.

[26] ACKERMAN J. The Villa: Form and Ideology of Country Houses. Princeton University Press, 1985.