Thermal-physiological Strategies Underlying the Sympatric Occurrence of Three Desert Lizard Species

2019-09-27XueqingWANGShuranLILiLIFushunZHANGXingzhiHANJunhuaiBIandBaojunSUN

Xueqing WANG, Shuran LI, Li LI, Fushun ZHANG, Xingzhi HAN, Junhuai BI*# and Baojun SUN

1 College of Life Science, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot 010022, Inner Mongolia, China

2 Key Laboratory of Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China

3 College of Life and Environmental Science, Wenzhou University, Wenzhou 325035, Zhejiang, China

4 Grassland research institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hohhot 010010, Inner Mongolia, China

5 College of wildlife Resources, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040, Heilongjiang, China

Abstract Sympatric reptiles are the ideal system for investigating temperature-driven coexistence. Understanding thermally physiological responses of sympatric lizards is necessary to reveal the physiological mechanisms that underpin the sympatric occurrence of reptiles. In this study, we used three lizard species, Eremias argus, E. multiocellata, and Phrynocephalus przewalskii, which are sympatric in the Inner Mongolia desert steppe, as a study system. By comparing their resting metabolic rates (RMR) and locomotion at different body temperatures, we aimed to better understand their physiological responses to thermal environments, which may explain the sympatric occurrence of these lizards. Our results showed that E. argus had significantly higher RMR and sprint speed than E. multiocellata, and higher RMR than P. przewalskii. In addition, the optimal temperature that maximized metabolic rates and locomotion for E. argus and E. multiocellata was 36°C, whereas for P. przewalskii it was 39°C. Our study revealed the physiological responses to temperatures that justify the sympatric occurrence of these lizards with different thermal and microhabitat p References and active body temperatures. Eremias argus and E. multiocellata, which have lower body temperatures than P. przewalskii, depend on higher RMR and locomotion to compensate for their lower body temperatures in field conditions. Our study also highlights the importance of using an integrative approach, combining behavior and physiology, to explore the basis of sympatric occurrence in ectothermic species.

Keywords Sympatric lizards, resting metabolic rate, locomotion, Eremias argus, E. multiocellata, Phrynocephalus przewalskii

1. Introduction

Understanding the mechanisms that allow species coexistence is one of the core issues in community ecology. Niche differentiation is considered to be the basis of coexistence among sympatric species. Niche differentiation is a process by which competing species utilize environmental resources differently, and it can include aspects such as activity period, use of space, and food p References (Hardin, 1960; Shurinet al., 2004). Pacala and Roughgarden (1985), for example, reported the existence of several anole lizards that shared food resources (i.e., insects) on the Caribbean islands but occupied different microhabitats such as leaf litter floor and branches to avoid any possible competition for microhabitats or food resources.Lophophorus sclateriandIthaginis cruentus, two pheasant species, were observed to share high-altitude habitats in Gaoligong Mountain but to feed on different plants or different parts of the same plants (Luoet al., 2016).

In ectotherms, performances of specific activities such as locomotion, immunity, growth, and even reproduction are greatly affected by body temperatures (Angilletta, 2009; Angillettaet al., 2002). Within thermal tolerance range, the physiological performance of ectotherms is known to enhance as body temperature increases until the optimal temperature is reached; after that, performance rapidly decreases if body temperature continues to increase (Huey and Kingsolver, 1989). Because of its effect on body temperature and thus on function and performance, environmental temperature is one of the most important ecological factors for ectotherm animals (Angilletta, 2009) and, therefore, is also considered an important resource (e.g., Liet al., 2017). Among sympatric ectotherms, different temperature p References may result in different body temperatures, which in turn may result in segregation of microhabitat utilization and allow sympatric occurrence (Adolph, 1990; Hertz, 1992; Martinvallejoet al., 1995; Wilkinson and Grover, 1996). Understanding how variation in thermal environment affects sympatric species has become a hot topic in animal ecology (e.g., Liet al., 2017; Osojniket al., 2013; Ruschet al., 2018; Žagaret al., 2015).

As ectotherms, sympatric lizards constitute ideal systems for investigating temperature-driven niche differentiation and coexistence (Pianka, 1986). Lizards can regulate their body temperatures in a narrow range mainly through behaviors to facilitate physiological functions (Adolph, 1990; Angilletta, 2009). On the Mongolian plateau, three ground-dwelling sympatric lizard species coexist in arid, semi-arid, or grass lands area:Eremias argus,E. multiocellata, andPhrynocephalus przewalskii(Zhaoet al., 1999). These sympatric species have been demonstrated to occupy different microhabitats (e.g., vegetation coverage) and to have significantly different thermal p References and active body temperatures.Phrynocephalus przewalskiimainlyselects open and warm microhabitats and has a higher preferred body temperature range (Tsel: 33.9-39.2℃) thanE. argus(Tsel: 32.8-37.5°C) andE. multiocellata(Tsel: 33.4-36.8°C), which occupy shaded and cool habitats (Table S1) (Liet al., 2017). Accordingly, the active body temperatures are significantly higher inP. przewalskiithan inE. argusandE. multiocellata(Table S1) (Liet al., 2017). These species’ demands for thermal environmental resources were speculated to be met because of microhabitat differentiation, which may be an important basis for their sympatric occurrence (Liet al., 2017).Nevertheless, as ectotherms, their body temperatures should be effective on fitness-related physiological functions before they affect their sympatric occurrences (Angilletta, 2009; Angillettaet al., 2002; Hochachka and Somero, 2002). Our current knowledge on these species’ differences regarding thermal preference or active body temperatures is insufficient to explain the effect of their thermal niche-partitioning on promoting their sympatric occurrence. Therefore, in order to reveal the physiological basis that underpins their temperature-driven sympatric occurrence, it is critical to investigate the effects of body temperature on important physiological traits ofE. argus,E. multiocellata, andP. przewalskii.

Metabolism is one of the most important physiological processes because it determines an organism’s demands from the environment and energy allocation among functions (Brownet al., 2004; McNab, 2002). Lizards’ metabolic rates have been demonstrated to be significantly sensitive to body temperatures; these, in turn, require the animals’ fast response to any environment thermal variation (e.g., Maet al., 2018a; Maet al., 2018b; Sunet al., 2018). For example, the metabolic rates were enhanced as body temperature increasing, and could respond to thermal variation by acclimation in lizard (e.g., Sunet al.,2018). Furthermore, the segregation of metabolic rates at the same temperatures may help niche differentiation (Žagaret al., 2018; Žagaret al., 2015). In addition, locomotion is thermal dependent and critical to escape danger, forage, and choose mating partners, and thus affects survival and reproduction in ectotherms (Robson and Miles, 2010; Shine, 2003; Shuet al., 2010; Wilson, 2001).

Here, with sympatricE. argus,E. multiocellataandP. przewalskiifrom Shierliancheng of Inner Mongolia area as a study system, we measured the metabolic rates and locomotion of each species at a range of body temperatures from 15-42°C in order to determine interspecific differences in physiology and fitness-related performances. We predicted that: 1)E. argusandE. multiocellata, which occupied shaded microhabitats and have lower active body temperatures, would have higher metabolic rates and sprint speeds but lower optimal temperatures for sprint speed thanP. przewalskiiat a same temperature within a moderate range before the optimal temperature is reached; 2) combined with temperaturerelated curves of metabolic rates and sprint speed, the three sympatric species would perform better when at their own active body temperatures under preferred microhabitat conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lizard collection and husbandryThe grounddwelling lizardsE. argus, E. multiocellata, andP. przewalskiiwere collected from late June to early July at the Shierliancheng field station, Institute of Grassland Research of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (111°09′ E, 40°21′ N, elevation 1010-1021 m), where the ground-dwelling lizards (i.e.,E. argus, E. multiocellata, andP. przewalskii) sympatry (Liet al., 2017). During collection, gravid female lizards were determined by palpate and released. Male and nongravid female adults of each species were transferred to our laboratory in Beijing, where they were weighed (to the nearest 0.001 g) and measured (to the nearest 1 mm). Every five or six lizards of each species were kept in a terrarium (550 × 400 × 350 mm3, length × width × height). The terraria were placed in a temperaturecontrolled room at 20°C with photoperiod cycles of 10 h dark: 14 h light (6:00-20:00). A heating bulb (50 w) was placed above one end of each terrarium to provide a temperature gradient inside the terrarium from 20-50°C within each photoperiod. Food (crickets dusted with vitamins) and water were providedad libitum.

2.2. Resting metabolic rateAfter seven days of husbandry, the resting metabolic rates (RMR) of 14E. argus(7 ♂ and 7 ♀), 13E. multiocellata(5 ♂ and 8 ♀), and 14P. przewalskii(7 ♂ and 7 ♀) (totaln= 41) were measured at ten test temperatures (15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36, 39, and 42°C), with one temperature every other day in a random sequence. Lizards were fasted for at least 12 hours before each measurement. Initially, each lizard was placed in an incubator (Sanyo, Japan) at the selected test temperature for 90 min; then, the lizard was placed in a respirometry chamber within the incubator and the measurement was performed. RMR was measured using a closed-flow respirometry system with a volume of 281.4 ml (Stable Systems International Inc. Las Vegas, NV, USA) and estimated via CO2production rate following a previously established method (Sunet al., 2018). In brief, the system contained the following modules: Universal interface II (UI2), Subsampler TR-S (SS3), Mass flow control unit (MFC-2), Oxygen analyzer (FC-10a), and Carbon dioxide analyzer (Ca-10a). At the beginning of each measurement, the system was opened for two to three minutes so that air came through an entrance tube with a flow rate of 300 ml/min to make the baseline stable. Afterward, the measurement system was transferred to a closed-circuit respirometry, and then carbon dioxide production rates (VCO2) in closedcircuit were continuously recorded for 10 min. The entire environment was dark (no light exposure) during measurements, and all measurements were conducted from 10:00-18:00 to minimize the effects of circadian rhythms. The metabolic rates were calculated as the CO2production per gram0.75of body mass per hour (ml/g0.75/hr) following the ‘metabolic theory of ecology’ (Brownet al., 2004), with the equation of metabolic rates =VCO2× volume/body mass, whereVCO2is the CO2production rate in percentage (%/hr) in the closed circuit with the volume of 281.4 ml (Sunet al., 2018). After each measurement, lizards were transferred back to the terraria until the next measurement initiated. After around 20 days of RMR tests, the locomotion tests were performed.

2.3. LocomotionThe locomotion of 37 lizards was determined using a 1 000 mm custom-made race track at ten test temperatures randomly (15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36, 39 and 42°C) after the RMR measurements. Locomotion measurements were not performed in fourE. argusas they were out of conditions (i.e., inactive or unwilling to move under stimulation) one day after the RMR experiments. Before the locomotion measurement, lizards were placed in an incubator at each test temperature for 90 min. The sprint speed was then determined in a 1 000 mm race track with photoelectric timers every 200 mm. For measurements, the lizard was placed in one end of the track and then stimulated on the tail with a paintbrush to run along the race track. The time spent by the lizard to run over every 200 mm interval was recorded using the photoelectric timer. Tests were conducted from 10:00-14:00. Each individual was tested twice with an interval of one hour between tests; the fastest speed of the two tests (i.e., 10 speed records) was recorded as the sprint speed for each lizard. Tests were conducted every other day.

2.4. Statistical analysisBefore statistical analysis, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test andLevene’stest were conducted to detect data normality and variance homogeneity. Repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted to determine species differences in RMR and locomotion, with species as a main factor and test temperatures as a repeated factor. When interaction between species and test temperatures was detected, a further comparison was conducted to analyze the differences among species at relevant test temperature ranges.

3. Results

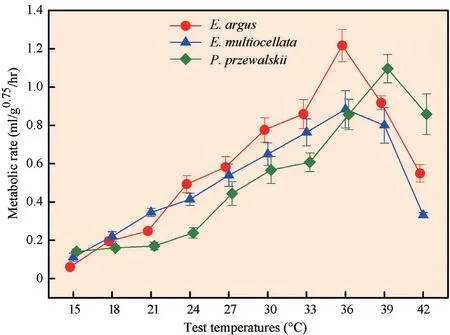

3.1 Resting metabolic ratesThe RMRs were significantly different among the three species.Eremias argushad a higher RMR thanE. multiocellataandP. przewalskii(E. argusa>E. multiocellatab>P. przewalskiib;F2,38= 3.65,P= 0.036) (Figure 1). RMR increased with test temperature until the optimal temperature was reached; then, RMR decreased as temperature continued to increase (repeated factor ‘test temperature’:F9,342= 97.956,P< 0.0001). The optimal temperature of RMR forE. argusandE. multiocellatawas 36°C, whereas forP. przewalskiiit was 39°C. The effect of the test temperatures on RMR was species-dependent. At low temperatures (from 15-36°C),E. argushad a significantly higher RMR thanP. przewalskii, withE. multiocellatain between (E. argusa>E. multiocellataab>P. przewalskiib;F2,38= 8.251,P= 0.001). At high temperatures (39-42°C), the RMR ofP. przewalskiiwas significantly higher than those ofE. argusandE. multiocellata(P. przewalskiia>E. argusb>E. multiocellatab;F2,38= 18.023,P< 0.0001) (Figure 1).

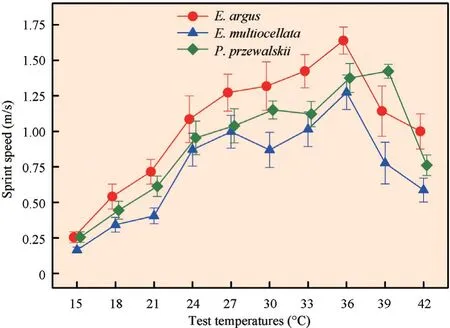

3.2. Locomotion Sprint speed ofE. arguswas significantly higher than that ofE. multiocellata, whereas sprint speed ofP. przewalskiiwas not significantly different from those of either species (E. argusa>P. przewalskiiab>E. multiocellatab;F2,34= 5.376,P= 0.009) (Figure 2). Test temperature had a significant effect on sprint speed (F9,306= 61.687,P< 0.0001). Sprint speed increased with temperature until the optimal temperature, after which it decreased as temperature continued to increase. The optimal temperature of sprint speed forE. argusandE. multiocellatawas 36°C, whereas forP. przewalskiiit was 39°C. At low temperatures (15-36°C), the sprint speed ofE. arguswas significantly higher than that ofE. multiocellata; the sprint speed ofP. przewalskiiwas not significantly different from those of either species (E. argusa>P. przewalskiiab>E. multiocellatab;F2,34= 4.439,P= 0.019). At high temperatures (39-42°C), the sprint speeds ofP. przewalskiiandE. arguswere similar and both higher than that ofE. multiocellata(P. przewalskiia>E. argusa>E. multiocellatab;F2,34= 6.792,P= 0.003) (Figure 2).

4. Discussion

On the basis of previously known thermal biology traits such as active body temperatures, and thermal preference of the sympatric lizardsE. argus,E. multiocellata, andP. przewalskii(Tables S1) (Liet al., 2017), in the present study we determined the interspecific differences in RMR and locomotion at different body temperatures from 15 to 42°C. We found thatE. argushave significantly higher RMR and locomotor performance, andE. multiocellatahas significant higher RMR, when compared toP. przewalskii, especially at low body temperatures from 15 to 36°C, but lower optimal temperatures for RMR and locomotion, which indicates the existence of a physiological adaptation to the decrease in body temperature that also influences their performances. Therefore, we found that physiology and performance are both fine-tuned to the thermal p References of the studied lizard species.

Figure 1 Resting metabolic rate (RMR) of Eremias argus, E. multiocellata, and Phrynocephalus przewalskii at 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36, 39, and 42°C. RMR was expressed as CO2 production per g0.75 body mass per hour (ml/g0.75/hr). Red circles, blue triangles, and green rectangles indicate the RMR of E. argus, E. multiocellata, and P. przewalskii, respectively. The optimal temperatures for E. argus, E. multiocellata, and P. przewalskii were 36°C, 36°C, and 39°C, respectively. Data are shown as mean ± SE. The RMRs (expressed as ml/g/hr) are also provided in Table S2, for the convenience of interspecific comparison in ‘Meta-Analysis’.

Figure 2 Locomotion of Eremias argus, E. multiocellata, and Phrynocephalus przewalskii at 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36, 39, and 42℃. Locomotion was expressed as sprint speed (m/s). Red circles, blue triangles, and green rectangles indicate the sprint speed of E. argus, E. multiocellata, and P. przewalskii, respectively. The optimal temperatures for E. argus, E. multiocellata, and P. przewalskii were 36℃, 36℃, and 39℃, respectively. Data are shown as mean ± SE.

The interspecific differences in metabolic rates amongE. argus,E. multiocellata, andP. przewalskiiare consistent with the differences that were observed in hatchlings incubated under fluctuant temperatures (Maet al., 2018a, 2018b). The metabolic rates of hatchlings ofE. argusandE. multiocellatawere higher than in those ofP. przewalskiiand enhanced with the increase in the test temperatures; this may indicate that the interspecific differences are fixed at the different life cycle stages of these species. As the fundamental physiological process, metabolic rates may reflect the organism’s physiological response to the environment (Brownet al., 2004; McNab, 2002). However, unlike endotherms—which have thermal neutral zones within which organismal metabolic rates are thermally insensitive—, ectothermic metabolic rates are significantly thermally dependent, with a slow increasing rate at low temperatures and a rapid increase at high temperatures, followed by a steep drop after optimal temperature is reached (Gilloolyet al., 2001; White, 2011). As the fundamental ‘pacemaker’ of biological rate, metabolic rate is related to lizard species’ body temperature, which is in turn affected by thermal environments (Brownet al., 2004; Glazier, 2015).Eremias argusandE. multiocellataselect shaded microhabitats and thus have lower body temperatures thanP. przewalskii(Table S1) (Liet al.,2017).Having high metabolic rates at low temperatures (15-36°C, Figure 1) may create advantages forE. argusandE. multiocellataat low temperatures by allowing the allocation of more metabolic energy for the performance of activities such as escaping or foraging (e.g., Sunet al., 2018; Whiteet al., 2012; White and Kearney, 2013). In contrast, as a higher RMR may enable a higher metabolic energetic production, a higher RMR at high temperatures inP. przewalskiimay be responsible for improving this species’ performance, accompanied by higher thermal p References and active body temperatures. Alternatively, a higher RMR at high temperatures may induce more energetic allocation for maintenance, which might be a cost (Sokolovaet al., 2012).

The existence of interspecific differences in locomotion across body temperatures has been demonstrated in numerous species of lizards(Chenet al., 2003; Duet al., 2000; Ji, 1995; Jiet al., 1996; Sunet al., 2014; Xu, 2001; Zhang and Ji, 2004). Locomotion could reflect the species’ ability to escape, forage, and even reproduce (Husak and Fox, 2006; Shuet al., 2010). The higher sprint speed inE. argusthan inP. przewalskiiandE. multiocellatamay result in selective advantages in escaping, foraging, and even reproduction, especially at low temperatures (Bergmann and Irschick, 2010; Xu, 2001; Zamora-Camachoet al., 2014).

As they are desert species, the optimal temperatures for sprint speed inE. argus(36°C),E. multiocellata(36°C), andP. przewalskii(39°C) are higher than those reported for skinks (32-34°C ) (Duet al., 2000; Ji, 1995; Xu, 2001) and grass lizards (28-34°C ) (Chenet al., 2003; Jiet al., 1996; Zhang and Ji, 2004). In addition, the high optimal temperature forP. przewalskiifound in this study is consistent with this species’ higher active body temperatures, thermal preference, and thermal tolerance (Liet al., 2017) if compared to the sympatricE. argusandE. multiocellata. The differences in optimal temperatures may be an evolutionary consequence of adaptation to different climatic environments (Zhang and Ji, 2004). Lizards in open and warm environments (e.g., deserts) tend to have high body temperatures, and their optimal temperatures for functions are normally positively correlated with body temperatures (e.g., Ji, 1995; Zhang and Ji, 2004). Potentially, active body temperatures and optimal temperatures for function may be both affected by habitat thermal environments through natural selection or acclimation (Gilbert and Miles, 2017; Sinclairet al., 2016). Within a species’ distribution area, other climatic factors (i.e., humidity) may also directly or indirectly induce variation in thermal traits in lizards, including optimal temperatures of thermal performance curve or critical temperatures (Sinclairet al., 2016; Sundayet al., 2012). Nonetheless, in the present study, these three sympatric species lived in adjacent microhabitats with very similar precipitation and evaporation indices (Wanget al., 2016); thus, we propose that the divergences in optimal temperatures of metabolic rates and locomotion among species were driven by thermal environments. However, future studies on the effect of multiple factors on thermal traits in sympatric ectotherms systems would be very important and necessary.

In general, the sympatric speciesE. argus,E. multiocellata, andP. przewalskiihave different preferred microhabitats, resulting in interspecies variation of thermal p References and active body temperatures (Table S1) (Liet al., 2017).Eremias argusandE. multiocellataresort to high physiological processes within a low temperatures range (i.e., 15-36°C) to compensate for their lower body temperatures in field conditions. Alternatively,P. przewalskiioccupies open and warm microhabitats, and it has higher body temperatures. Lower metabolic rates and sprint speed at low body temperatures may be an adaptive strategy forP. przewalskii; its low energetic production at low body temperatures results in a lower energetic cost—indicated by low sprint speed—, which in turn reduces energy expenditure (Brownet al., 2004; Younget al., 2011). Similarly, within a certain geographical scale, populations or species that occupy warm habitats (e.g., tropical region) also have higher body temperatures, and therefore tend to have lower performance (e.g., swimming speed) and metabolism rates when compared to species from cold environments at even temperatures, as ‘Metabolic Cold Adaptation’ predicts (e.g., Whiteet al., 2012). Given that, the combination of different active body temperatures and physiological trait responses is an effective solution that allows the sympatric occurrence of the three desert lizards, by enabling their functions within an active body temperature range. Our study highlights the importance of integrative investigations on temperature-driven sympatric occurrence at a physiological level, based on thermal biological traits and active body temperatures. Future studies should focus on the dynamic of the effects of body temperatures on physiological responses in field to reveal the modification of physiological and body temperatures to thermal variation. Especially in the context of climate warming, studies integrating body temperatures alterations and thermal performance curves may provide insight into the responses and the evaluation of the vulnerabilities of sympatric species (Sinclairet al., 2016).

AcknowledgementsWe thank WANG C. X. and MA L. for their assistance. Animal Ethics Committees at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences approved the ethics and protocol (IOZ14001) for the collection, handling, and husbandry of the study animals. BI J. H. (No.31660615) and SUN B. J. (No. 31870391 and 31500324) are supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

杂志排行

Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- A New Species of Megophryid Frog of the Genus Scutiger from Kangchenjunga Conservation Area, Eastern Nepal

- Mitochondrial Diversity and Phylogeographic Patterns of Gekko gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae) in Thailand

- Molecular Cloning and Putative Functions of KIFC1 for Acrosome Formation and Nuclear Reshaping during Spermiogenesis in Schlegel’s Japanese Gecko Gekko japonicus

- Altitudinal Variation in Digestive Tract Lengh in Feirana quadranus

- The Marking Technology in Motion Capture for the Complex Locomotor Behavior of Flexible Small Animals (Gekko gecko)