A New Species of Megophryid Frog of the Genus Scutiger from Kangchenjunga Conservation Area, Eastern Nepal

2019-09-27JanakRajKHATIWADAGuochengSHUTulsiRamSUBEDIBinWANGAnnemarieOHLERDavidCANATELLAFengXIEandJianpingJIANG

Janak Raj KHATIWADA, Guocheng SHU, Tulsi Ram SUBEDI, Bin WANG, Annemarie OHLER, David C. CANATELLA, Feng XIE and Jianping JIANG,5*

1 Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610041, China

2 Centre for Marine and Coastal Studies (CEMACS), Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang 11800, Malaysia

3 Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, CNRS MNHN UPMC EPHE, Sorbonne Universités, CP 30, 75005, 25 rue Cuvier, Paris 75005, France

4 Department of Integrative Biology, University of Texas, Austin, USA

5 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

Abstract This study investigated the systematics of the megophryid genus Scutiger from eastern and western Nepal using molecular and morphological data. Our results support two divergent lineages, one of which has nuptial spines on the dorsal surface of the first three fingers while the other has spines only on the dorsal surface of the first two fingers. The Ghunsa lineage from eastern Nepal shows significant morphological and molecular differences to other species of genus Scutiger and is here described as a new species. Based on the molecular analysis, the Muktinath lineage from western Nepal is confirmed to be Scutiger boulengeri and represents a species complex widespread throughout the Himalayan region. The newly described taxon is endemic to the eastern Himalayas and currently known only from the Ghunsa valley, Taplejung district, Nepal.

Keywords Scutiger, New species¸ Eastern Himalaya, Nepal

1. Introduction

The Eastern Himalayas is one of the biological hotspots in Asia and a place of endemism where new species of vertebrates and invertebrates have been discovered in recent years (Agarwal et al., 2014; Khatiwada et al., 2017; Khatiwada et al., 2015; Mahony et al., 2011). The Kangchenjunga Conservation Area (KCA) is a part of the Eastern Himalayas with high topographical, hydrological and climatic variability (WWF 2007) and is rich in floral and faunal diversity. Furthermore, this region is situated at the transition zone of Palaearctic and Oriental zoogeographical realms (Olson et al., 2001) and therefore species in this region have a close affinity with both realms (Che et al., 2010). The Eastern Himalaya occupies the world’s largest elevation gradient from 60 to 8848 meters, within a 150 -200 kilometers (Dobremez 1976). Fast flowing rivers created sharp and deep river gorges in this region promoting geographic isolation that hinders gene flow, thus leading to speciation and endemism (Agarwal et al., 2014; Che et al., 2010). Amphibians, being poor dispersers and generally philopatric (Smith and Green 2005), and may be expected to have increased rates of genetic differentiation in this region compared to other vertebrate species.

Members of the genus Scutiger Theobald, 1868 have been reported from southwestern China (including Tibet), northern Myanmar, northern India and Nepal (Fei et al., 2012; Frost 2018). Twenty-one species of Scutiger are known, and among these are species in the mountains of central Asia that have the largest elevational range (1000-5300 m) of any amphibians (Subba et al., 2015) (Table S1). Over the last 15 years several species in the family Megophryidae Bonaparte, 1850 have been described from the Eastern Himalayas and adjacent region (Jiang et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2013; Orlov et al., 2015; Sondhi and Ohler 2011; Yang et al., 2016), reflecting an increase in amphibian taxonomic diversity.Nevertheless, only one species of Scutiger has recently been described from this region (Jiang et al., 2016). In Nepal, two megophryid genera, Xenophrys Günther, 1864 and Scutiger are known, with four species of Scutiger toads reported (Dubois 1974; 1987). The first record of a Nepalese Scutiger was Scutiger boulengeri, described as Cophophryne alticola from the Kharta Valley by Procter (Procter 1922) and also reported by others (Dubois 1974; 1987; Nanhoe and Ouboter 1987) from Mukthinath. Scutiger sikimmensis (Blyth 1854) was first recorded from Langtang by Smith (1951), later by Dubois (1974) with new collections from the same locality. Dubois (1987) reported specimens from a series of Nepalese locations (Thankur, Ghorapani, Langtang, Namche Bazar and Jalijale). Nanhoe and Ouboter (1987) confirmed its presence in Ghorapani area of Annapurna Conservation Area. The specimens reported by Smith and Battersby (1953) from Maharigaon (western Nepal) were later allocated to Scutiger nyingchiensis, now S. occidentalis by Dubois (1987). Scutiger nepalensis was described by Dubois in 1974 based on specimens from Khaptad area, and has since been collected from Dharpatan Dhule in western Nepal (Dubois 1987);Nanhoe and Ouboter (1987) extended the distribution to Gurja Ghat. Recently, Hofmann et al., (2017) carried out a molecular phylogenetic analysis of genus Scutiger from all across its distributional range using both mitochondrial and nuclear markers. Their study provided updated genetic insight of genus Scutiger from Nepal and other areas, and further recognized Scutiger nepalensis and Scutiger sikkimensis from the Nepalese Himalaya as highly divergent.

During field surveys in 2015 and 2016 in the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area (Taplejung district, eastern Nepal) and in the Annapurna Conservation Area (Mustang district, western Nepal), we collected a series of adult specimens and tadpoles that were assigned to the genus Scutiger based on the following characters: (1) enlarged paratoids; (2) granular dorsal surface; (3) absence of vomerine and maxillary dentition; (4) hidden tympanum; (5) finger and toes free of webbing; (6) absence of digital pads on fingers and toes; (7) fingers of breeding males with black nuptial spines and with pectoral and axillary glands. Detailed morphological and molecular analyses suggested that Ghunsa specimens are genetically and morphologically distinct from previously known species of genus the Scutiger. Thus, we provide a description of the Ghunsa population of Scutiger as a new species.

2. Materials and Methods

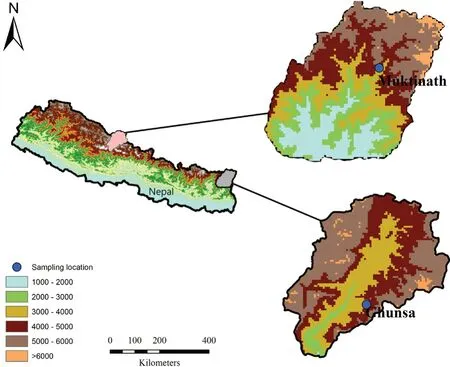

2.1. SamplingFieldwork was carried out between May to September in 2015 and 2016 in eastern and central Nepal (Figure 1). Multiple survey methods were used; for example, visual encounter surveys, acoustic surveys, and leaf litter searches were made during the night (1900h-0000h) as described by Khatiwada et al., (2016) and Khatiwada et al., (2019). Specimens were collected by hand, euthanized using 20% Benzocaine gel, tissue samples were collected, and specimens later fixed in 4% formalin for 24 h and then preserved in 70% ethanol. Tadpoles and eggs at different developmental stages were also sampled from the same location as the type series. These samples were preserved in 70% alcohol. Tissue samples were taken by clipping the fourth toe from adults and small portion of tail muscle of tadpoles, which were then preserved to 95% ethanol for molecular analysis. All amphibians handling and processing were in accordance with the guidelines of the Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation, Nepal and Animal Care and Use Committee of Chengdu Institute of Biology, CAS.

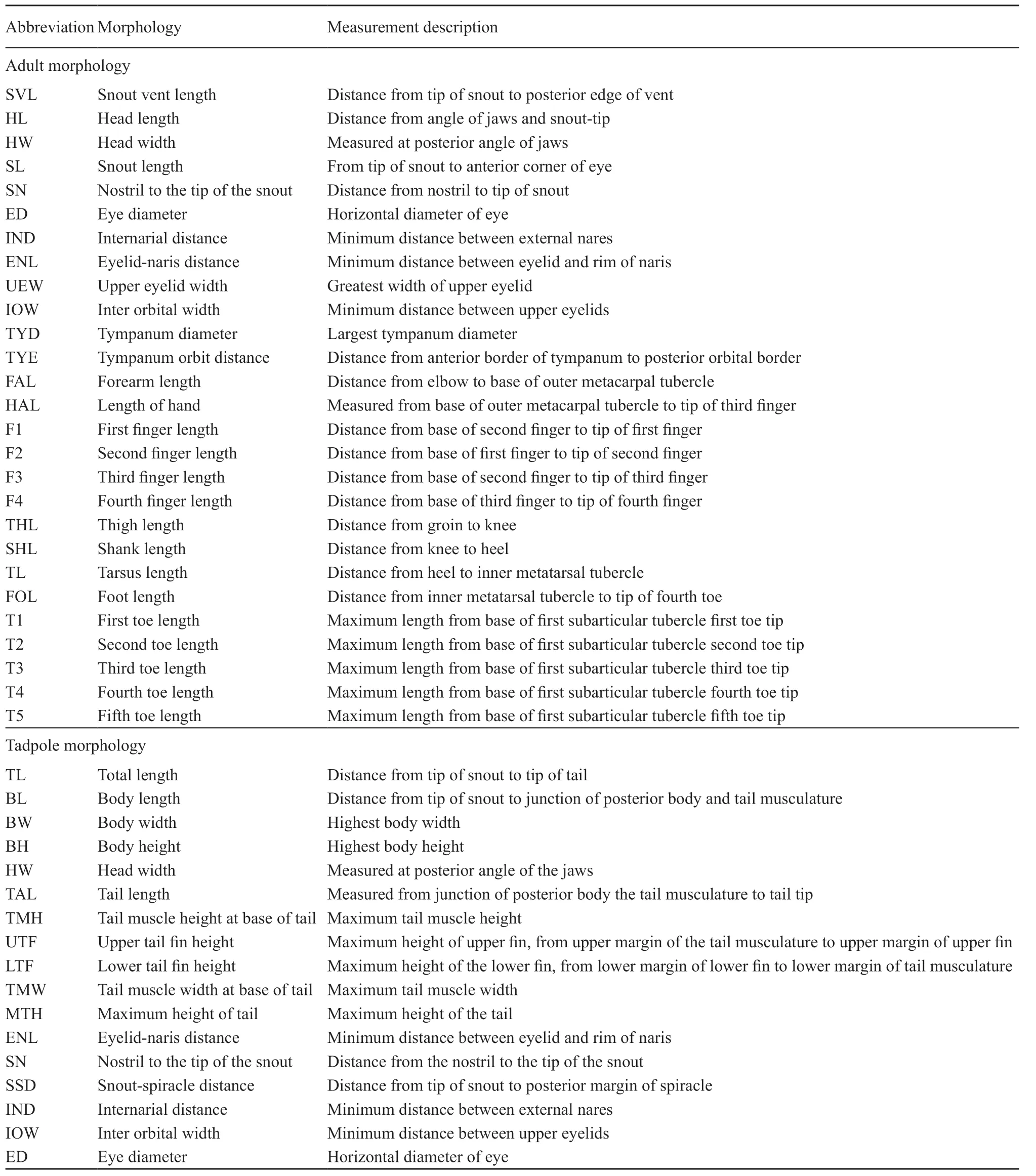

2.2. Morphological analysesMorphological measurements were taken using digital calipers (to nearest 0.1 mm). Measurement descriptions are provided in Table 1. Preserved Scutiger specimens were also measured in the herpetological museum of Chengdu Institute of Biology (CIB), Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu, China, and at the Collection des Reptiles et Amphibians of Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (MNHN), Paris, France. A total of 83 individuals (51 males and 32 females) of Scutiger from nine species were examined (Table S2).

Figure 1 Study area map showing sampling sites in Nepal

Table 1 Morphological characters used and their measurement descriptions for adults and tadpoles.

2.3. Statistical analysisA one-way Analysis of Variance ANOVA was used to test for differences among the new species, S. boulengeri, and S. nepalensis, followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test for pairwise differences. Prior to Principal Component Analysis (PCA), all morphometric data were regressed against SVL and the regression residual of each morphological trait was used as input data for the PCA. Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was used to test the morphometric differences between species by using scores from the principal components (those with eigen-value > 1) as dependent variables and species as independent variables (groups). Statistical analysis was performed in R package vegan (Oksanenet al., 2016) in R-software version 3.3.0 (R Development Core Team 2016).

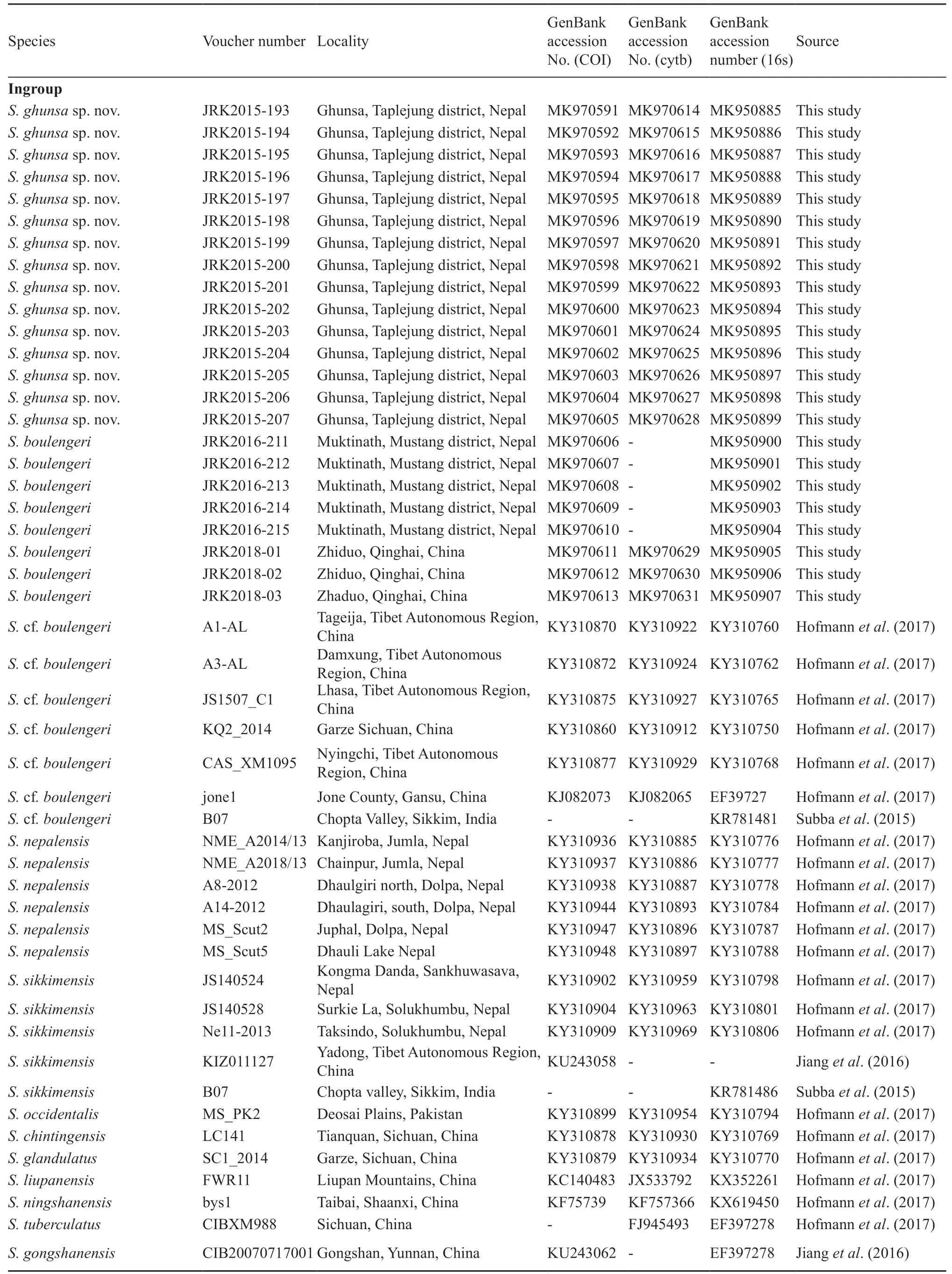

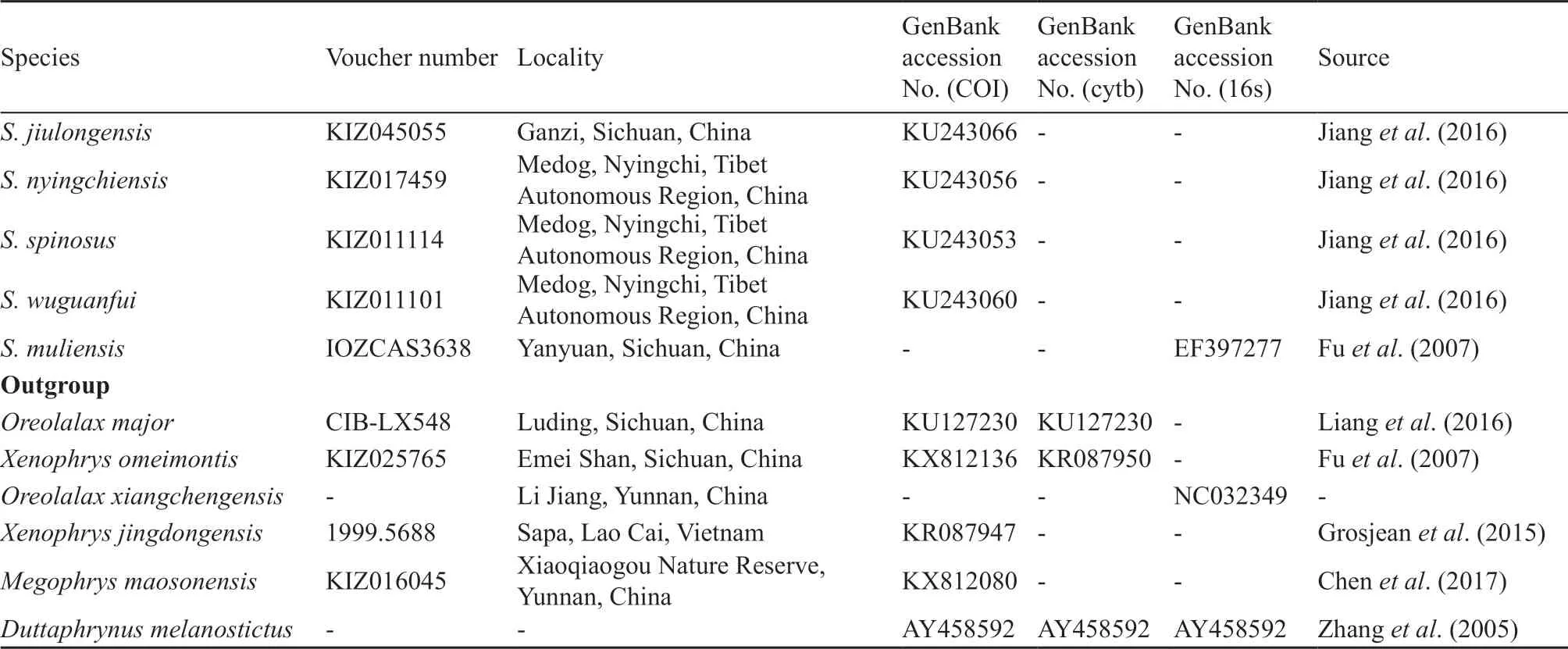

2.4. Molecular systematics analysesThe phylogenetic position of the Ghunsa population ofScutigerwas determined in relation to otherScutigerspecies through analysis of DNA sequence data. Total genomic extraction was carried out on clipped toe or muscle preserved in 95% ethanol using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (QIAGEN). The phylogenetic position of the Ghunsa population ofScutigerwas determined in relation to otherScutigerspecies through analysis of DNA sequence data. The mitochondrial gene 16S ribosomal RNA gene (16S rRNA), complete cytochrome C oxidase 1 gene (COI) and cytochrome b (cytb) from all samples were sequenced and amplified using primers as detailed by Cheet al., (2012). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and thermocycling conditions were set as described by Cheet al., (2012). The amplified PCR products were purified using Qiagen PCR purification kit and sequenced were obtained from an ABI 3100 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Newly obtained sequences were deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers (16s: MK950885-MK950907, COI: MK970591-MK970613, Cytb: MK970614-MK970631). Available nucleotide sequences ofScutigerspecieswere downloaded from the NCBI Genbank database and a list of species included in our analysis is provided in Table 2. ClustalW built into BIOEDIT Version 7.1.9 was used to align the nucleotide sequences (Thompsonet al., 1997) using the default parameters. Alignments were also checked and manually edited as needed.

Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses were employed to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships among the taxa based on haplotypes of the concatenated sequences of three genes (16S, COI and cytb), and COI, and 16S individually. ML analysis was conducted with the rapid bootstrapping algorithm using the program RAxML v8.00 (Stamatakis 2014) on the CIPRES Science Gateway server v3.2 (Milleret al., 2010). Nodal support for ML was assessed with 1000 rapid bootstrap replicates (BS).

PartitionFinder v1.1.0 (Lanfearet al., 2017) was used to find the optimal evolutionary models for Bayesian inference analysis based on Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values (Darribaet al.,, 2012). For the concatenated mtDNA, seven potential data block partitions were defined, one block for 16s rRNA gene and six blocks representing the three codon positions of each of the two protein-coding genes (CYTB and COI). BI analyses were conducted using MrBayes 3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003). Two independent runs were initiated, each with four simultaneous Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains, for 20 million generations and sampled every 1000 generations. The adequacy of convergence of chains and burn-in period was determined by examining plots of log-likelihood scores and the standard deviation of split frequencies. , The first 25% generations were discarded as burn-in, and the remaining samples were used to create a 50% majorityrule consensus tree and estimate Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP). The graphical viewer Figtree (Rambaut 2007) was used to edit the output of RAxML and MrBayes analyses. Uncorrected k2p pair-wise distances within and across genus for COI gene sequences were calculated with MEGA7 using the complete deletion option (Kumaret al., 2016).

3. Results

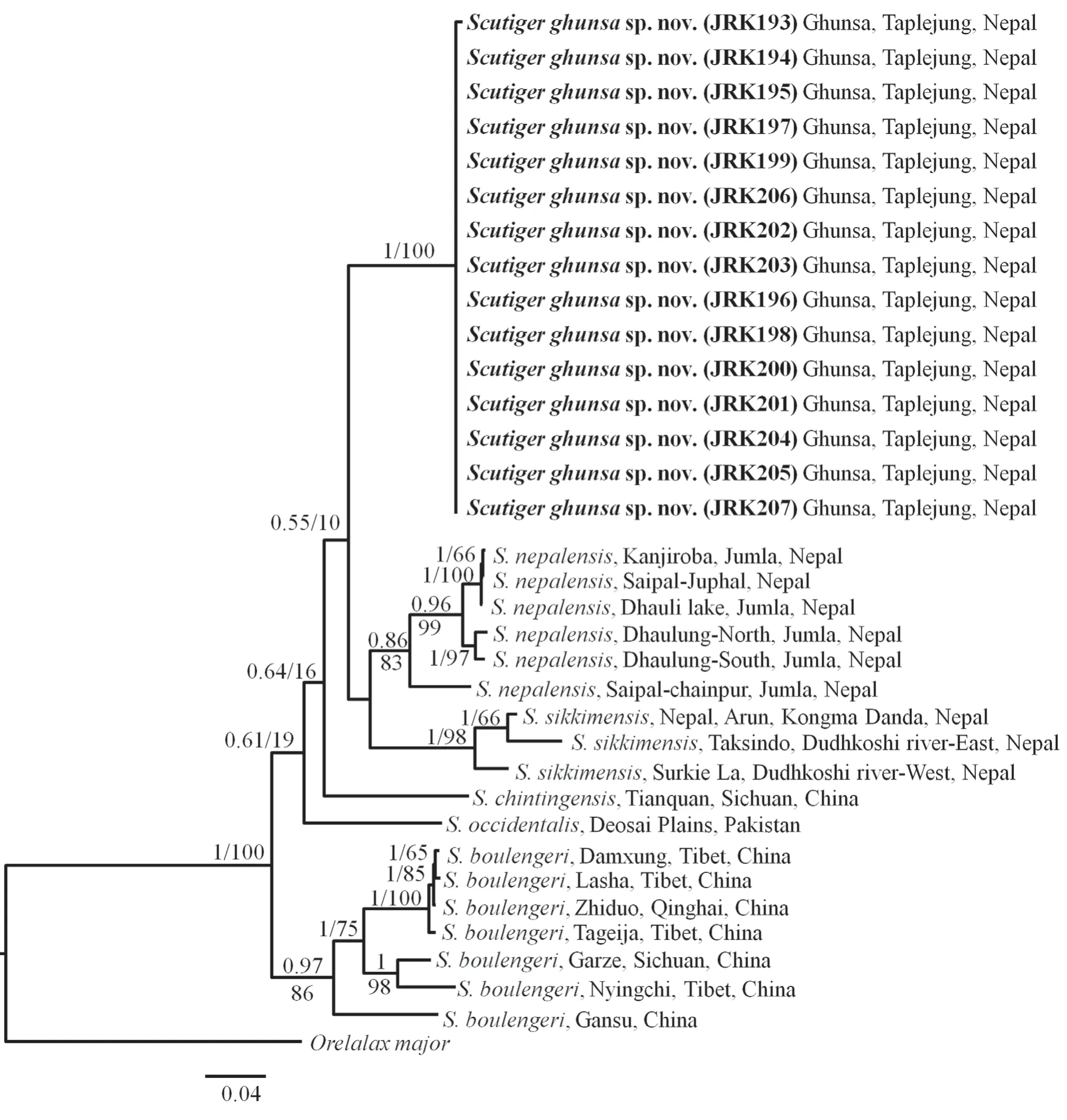

Phylogenetic relationships of mtDNA haplotypesThe aligned dataset of concatenated DNA sequences of the mitochondrial genes (16S, COI and Cyt-b) had a total length of 1939 bp. The maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) phylogenetic trees constructed from concatenated DNA sequences produced similar topologies with strong node support (Figure 2). The phylogenetic analysis indicates that the population ofScutigerfrom Ghunsa, (Kanchenjunga Conservation Area) is weakly supported as the sister taxon to a clade composed ofS. nepalensisandS. sikkimensis. SeveralS. boulengeriwere identified and it was misidentified asS. mammutusby Hoffmanet al.,(2017).

Based on the COI gene only, theScutigerpopulation from Muktinath (Mustang district, Annapurna Conservation Area, western Nepal) was genetically similar toScutiger boulengerifrom nearby neotype locality (Zhiduo and Zhadao counties, Qinghai, China)and clustered together in the phylogenetic tree (Figure S1). Furthermore, the uncorrected COI genetic distances among the Ghunsa population ofScutigerfrom the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area were <0.01%. The distances to the closet congener,S. nepalensiswere 7.4%-11.8%. The genetic divergences between the Ghunsa population and other two known species ofScutigerin Nepal,S. sikkimmensisfrom Arun river basin, eastern Nepal, see in Hofmannet al., (2017)andS.cf.boulengerifrom Mustang, Annapurna Conservation Area, western, Nepal were 10.10% to 11.4% and 10.10% to 10.3% respectively.

Figure 2 Bayesian inference (BI) tree based on concatenated DNA sequences of 16S, COI and Cytb. The values on branches are Bayesian posterior probabilities (bpp) followed by ML bootstrap supports (bs).

WithinS. nepalensis(the clade of six specimens from Jumla district-Hofmannet al., [2017]) and the sample from Saipal mountain, Chainpur, Jumla district, Nepal showed 5.5-5.8% genetic divergence from other individuals of this group. WithinS. sikkimensisgroup, the sample from Yadong, Tibet, China (see details in Jianget al., [2016]) showed 9.9% divergence from populations from Kongma Danda, Arun River, Taksindo, Dudhkoshi River (east), and Surkie La, (see in Hofmannet al., [2017]). Furthermore, within samples ofS. sikkimensisin Nepal, Surkie La, Dudhkoshi river (west) population showed 7.1% genetic divergence from the Kongma Dandaand Taksindo, populations (Figure S1).

Based on 16S sequences alone,S. sikkimensisfrom Sikkim, India showed lower genetic distances (0.00-0.20%) from of the Kongma Danda and Taksindo) populations (Figure S2).Scutiger boulengerifrom Muktinath, Mustang, Nepal were genetically very similar with the specimens from Zhiduo and Zhadao, Qinghai, China and Tageija, Damxung and Lasha, Tibet, China (Figure S2) with genetic distances of only 0.1 to 0.3%.Scutiger boulengerifrom Sikkim, India were also genetically very similar withScutigerfrom Muktinath, Nepal; the genetic distance between them was 0.4%

Table 2 Samples used in molecular analysis with GenBank accession numbers.

(Continued Table 2)

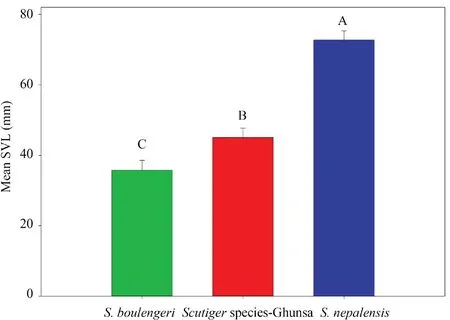

Morphometric analysisMorphometric comparisons were used to verify the distinctiveness of the lineages identified by molecular studies. Based on phylogenetic analysis,theScutigerpopulationfrom Ghunsa was closely related toS. nepalensis.Therefore, quantitative and multivariate analysis was performed from three species ofScutiger(ScutigerGhunsa population,S. nepalensisandS. boulengeri) known to occur in Nepal. InScutigerGhunsa population, females were significantly larger than males in SVL (t= -4.50,p= 0.006,df= 8). Due to lack of females ofS. nepalensis, we only used males for the further morphological comparisons. Oneway ANOVA showed that mean SVL varied significantly among the three species, ranging from 33.8 to 76.0 mm among males (one-way ANOVA,p< 0.001;F= 177.3). Further, post hoc analyses revealed that the mean SVL was significantly different among the three species (Figure 3).

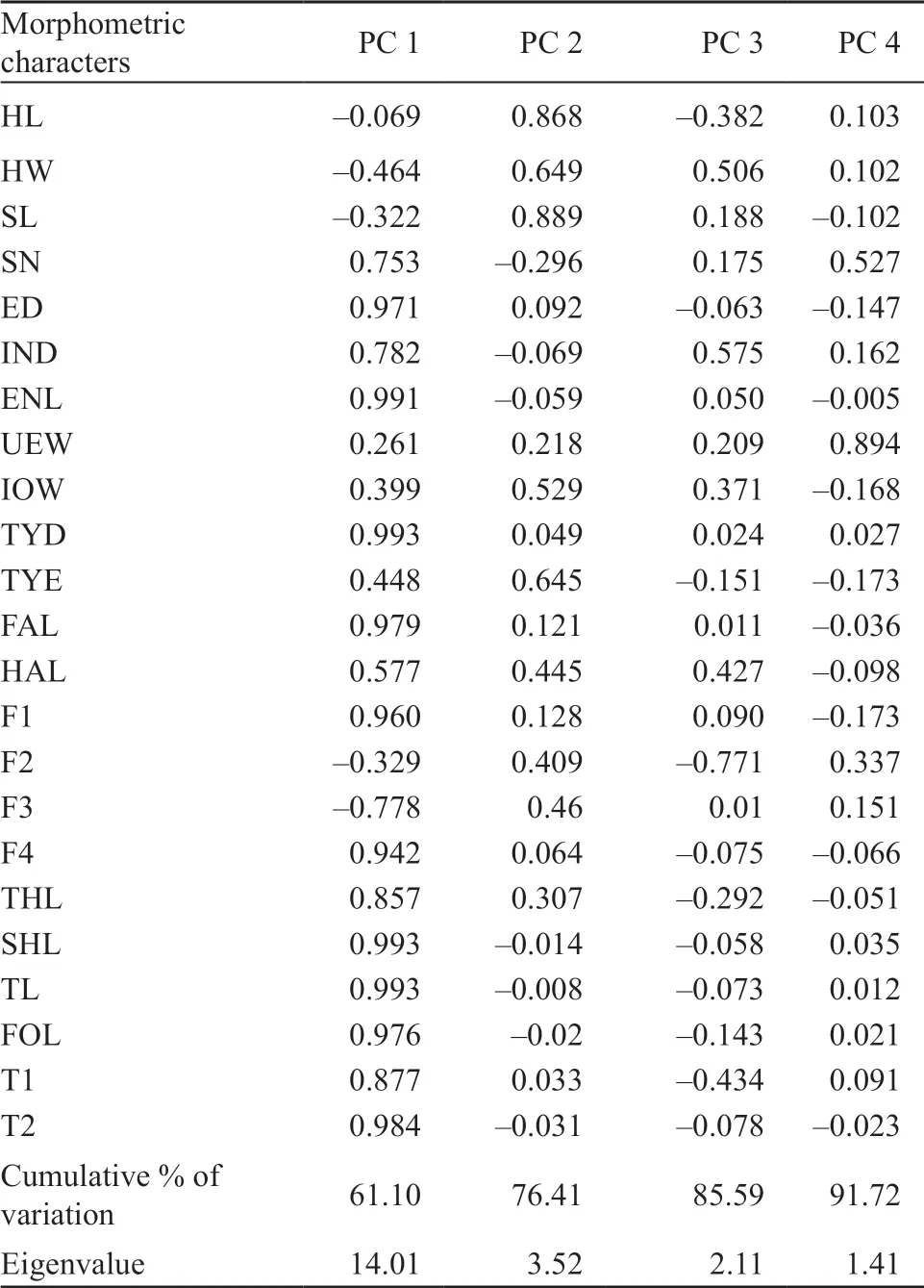

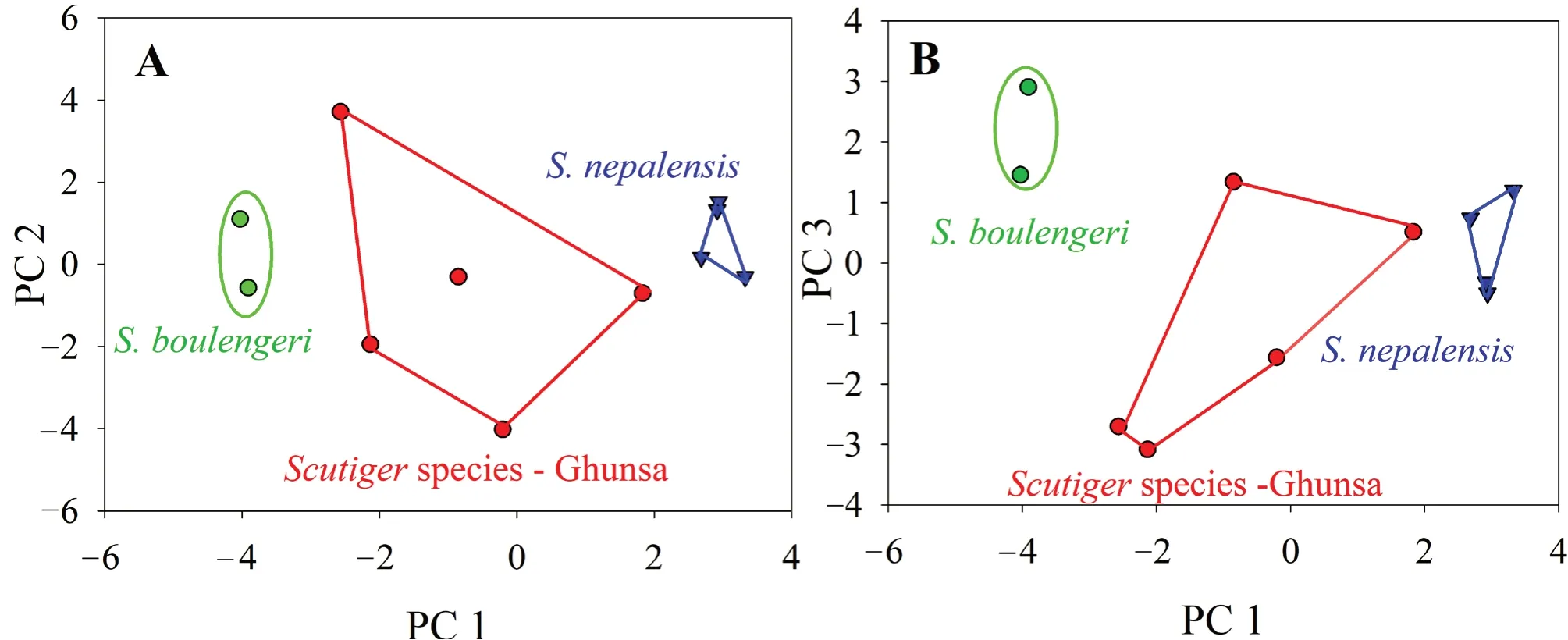

The Principal Component Analysis extracted four components with eigenvalues > 1.0 which accounted for 91.7% of the variation in the dataset. The first three components explained 85.6% of total variation. In PCA plots, the first two principal components (PC1 vs PC2; Figure 4A) and the first vs. the third principal components (PC1 vs PC3; Figure 4B) for males separated the three species from each other. Species variation along PC1 describes essentially the variation in morphological traits with longer length of the nostril to eye distance, inter orbital width, inter narial width, length of hand, 2nd finger, 4th finger, length of tarsus, length of meta-tarsus, 1st toe, 2nd toe, 3rd toe, 4th toe, 5th toe having positive scores whereas, species with shorter morphological traits have negative scores along the PC2 (Table 3). All the threeScutigerspecies were significantly different in morphometric shape (MANOVA, Wilks’ λ = 0.035,F= 8.57,p< 0.001). The difference was in accordance with the PCA results.

SystematicsThese results confirmed that there is substantial genetic divergence between the specimens from Ghunsa and other knownScutigerspecies, and support that this population is a distinctly evolving lineage, representing an undescribed species. This population also presents distinct morphological characteristics that are not observed in the closely related speciesS. nepalensis,which has smaller nostril-to-eye distance, inter-orbital width, inter-narial width, shorter length of hand, 2nd finger, 4th finger, length of tarsus, length of meta-tarsus, 1st toe, 2nd toe, 3rd toe, 4th toe and 5th toe. Based on molecular and morphological evidence, we hereby describe the specimens collected from Ghunsa, Taplejung district, Kangchenjungha Conservation Area, Nepal as a new species.

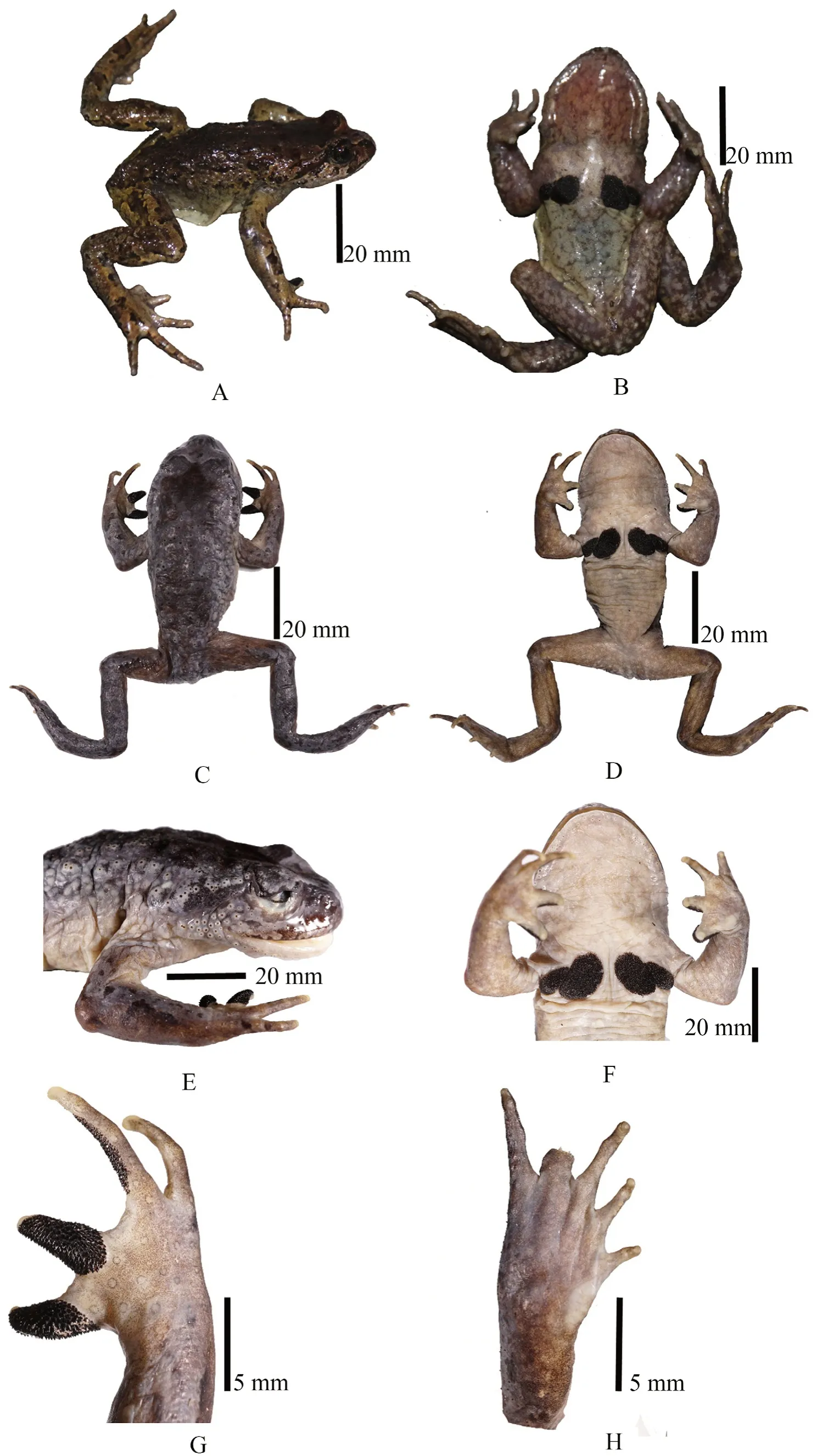

Species Account:Scutigerghunsasp. nov. (Figure 5)Local Name: Ghunsa alpine toad Nepali Name: Ghunsa Khasre Bhyaguto

Figure 3 Body size (mean±SD) variation among male Scutiger species. The bar represents the mean SVL and error denotes the standard deviation. The statistics derived from a one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test. The different letters above the bar signify the significant difference at 0.05.

Holotype:NHM-TU-17A-0116 (Figure 5), an adult male collected from Ghunsa Khola (Khola means “stream” in Nepali) Ghunsa, Taplejung district, Nepal, 27.66185°N, 87.93168 °E, elevation 3475 m a.s.l. collected by Janak Raj Khatiwada between 19:30 and 20:00h on 28thMay 2015 and deposited in the collection of the Natural History Museum, Tribhuvan University, Soyambhu, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Suggested common name:Ghunsa High Altitude Toad

Etymology:The species name is derived from the name of the type locality. It is hoped that this name will raise awareness to the local people about this new species and will further help to conserve the flora and fauna in this area. The specific epithet is a noun in apposition and is invariable in gender.

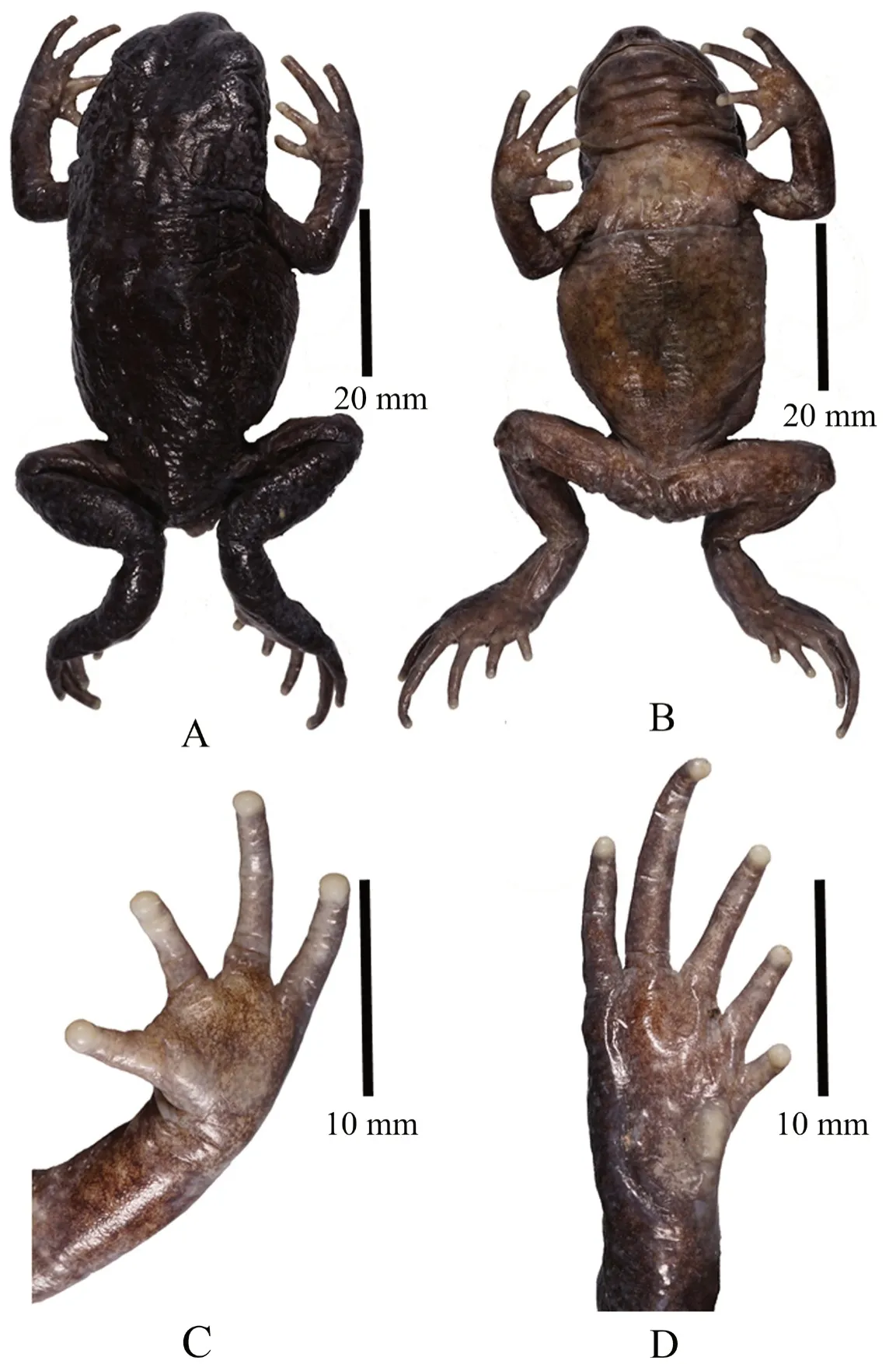

Paratypes:NHM-TU-17A-0117 (adult male) and NHMTU-17A-0118 (adult female, Figure 6) from the same location of as the holotype. The specimens are deposited in the collection of the Natural History Museum, Tribhuvan University, Soyambhu, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Diagnosis:Scutigerghunsasp. nov. is assigned to the genusScutiger, based on both molecular phylogenetic data and the following morphological characters: (1) enlarged paratoids; (2) dorsal surface granular in adult males; (3) vomerine and maxillary dentation absent; (4) hidden tympanum; (5) finger and toes free of webbing; (6) absence of digital disk on fingers and toes; (7) inner three fingers of breeding males with black nuptial spines in adult males; (8) breeding males with pectoral and axillary glands.

Scutigerghunsasp. nov is distinguished from all other known species ofScutigerby having the following morphological characters: (1) adult with medium body size, SVL 42.1-47.2 mm in males and 50.2-53.9 mm in females; (2) head wider than longer; (3) snout shorter than 20-40% of head length; (4) eye shorter than 20% of head length; (5) interorbital distance longer than internarial distance; (6) maxillary teeth absent; (7) vocal sac absent; (8) odontoids present on the lower mandibles; (9) hidden tympanum; (10) length of arm 20-40% of SVL; (11) hand length shorter than 20% of SVL (12) breeding males with pectoral and axillary glands; (13) inner pectoral gland almost twice the size of outer gland in breeding males; (14) nuptial spines on dorsal surface of first, second and lateral surface on third fingers in breeding males; (15) finger and toes free of webbing; (16) subarticular tubercles absent (17) dorsal surface of body and limbs granular; (18) belly of breeding males without spines. For detailed morphological comparisons, see Table 4.

Description of holotype (all measurements in mm)

Moderate body size (SVL 43.6); head wider than long (HW 16.4, HL 11.4, HW:HL 143 %); snout short and round (SL:HL 41.6%); large paratoid glands on either side of head between posterior corner of eye to armpit (axills) (7.1 mm); canthus rostralis distinct; nostril dorsolateral, just below canthal ridge; loreal region slightly concave, eyes large and convex (ED 6.3); eye diameter almost similar to snout length (ED:SL 99 %); tympanum and supratympanic fold absent; interorbital space flat, interorbital distance (IOD 5.3), greater than width of the upper eyelid (UEW 4.3); internarial surface flat (ENL 4.0); choanae small; vomerine teeth and ridges absent; maxillary teeth absent; tongue oval, deeply notched posteriorly, lingual papillae absent; openings of vocal sacs absent.

Table 3 Summery table of PCA statistics showing: character loadings, Eigenvalues, and percentage of explained variance for Principal Components (PC) 1-4.

Figure 4 Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on male specimens of Scutiger from Nepal based on 24 morphometric traits. Prior to Principal Component Analysis (PCA), all morphometric data were regressed against SVL and regression residual of each morphological trait was used in a PCA.

Arm robust, short (FAL:SVL 23%) and shorter than hand (HAL:SVL 54%); relative finger lengths I<II<IV<III; third finger (F3 5.9) shorter than arm (FAL 10); fingers tip round, not dilated; fingers without distinct lateral fringes, webbing absent; subarticular tubercles indistinct; flat, large and ovoid metacarpal tubercles, inner tubercle almost equal in size to outer tubercle; nuptial spines on dorsal and lateral surface of first and second fingers, but only on inner side of third finger.

Hindlimbs powerful and long, tibiotarsal articulation reaches tympanum when hindlimb pressed parallel to body; shank (SHL 17.5) almost equal to thigh (THL 17.0) but tarsus short (TL 11.1), foot length longer (FOL 19.2) than shank and thigh; toes thin and long, relative length I<II<III<V<IV (fourth toe of right foot cut for molecular analysis); toe tips round; weakly webbed; subarticular tubercles indistinct; inner metatarsal tubercle flat and oval; outer metatarsal tubercle poorly developed; supernumerary and plantar tubercles absent.

Skin texture:Skin of dorsum rough with scattered warts bearing black spines, density of warts and granules increasing towards vent; dorsal surface of snout and interorbital region smooth; few scattered tubercles on upper and lower mandibles; dorsal surface of forelimbs and hindlimbs with smaller tubercles than back; flanks with larger white warts or granules; side of shank with white warts or glandular tubercles without spines; a pair of pectoral and axillary glands present on chest, pectoral glands two times longer than axillary glands, glands covered by minute, dense black spines; vent surrounded by granules.

Colouration in life:An olive brown triangular spot on snout and interorbital region; posterior surface of head and dorsal body light brown; alternating olive brown and dark brown bands on upper lip; iris golden; forelimbs and hind limbs olive brown; irregular black spots on both limbs including fingers and toes; flanks light brown and gradually fading into creamy yellow ventrally. Ventral surface of head light brown; chest and abdomen creamy white with irregular light gray-brown lines; ventral surface of limbs brown with small irregular creamy white spots.

Colouration in preservation:In ethanol, olive brown triangular spot on snout and interorbital region fading to white; dorsum body, head and upper limbs brownishblack; ventral surface of belly creamy white; limbs light brownish-black; black spines more distinct on shank and thigh; and iris black.

Figure 5 Holotype of Scutiger ghunsa sp. nov. (NHM-TU-17A-0116, adult male). in life: A. dorsolateral view, B. ventral view. In preservative: C. dorsal view, D. ventral view, E. lateral view, F. ventral view of chest, G. Dorsal surface of hand, H. ventral surface of foot.

Figure 6 Paratype of Scutiger ghunsa sp. nov. NHM-TU-17A-0117, adult female, SVL 47.8 mm. A. dorsal view; B. ventral view; C. ventral surface of hand; and D. ventral surface of foot.

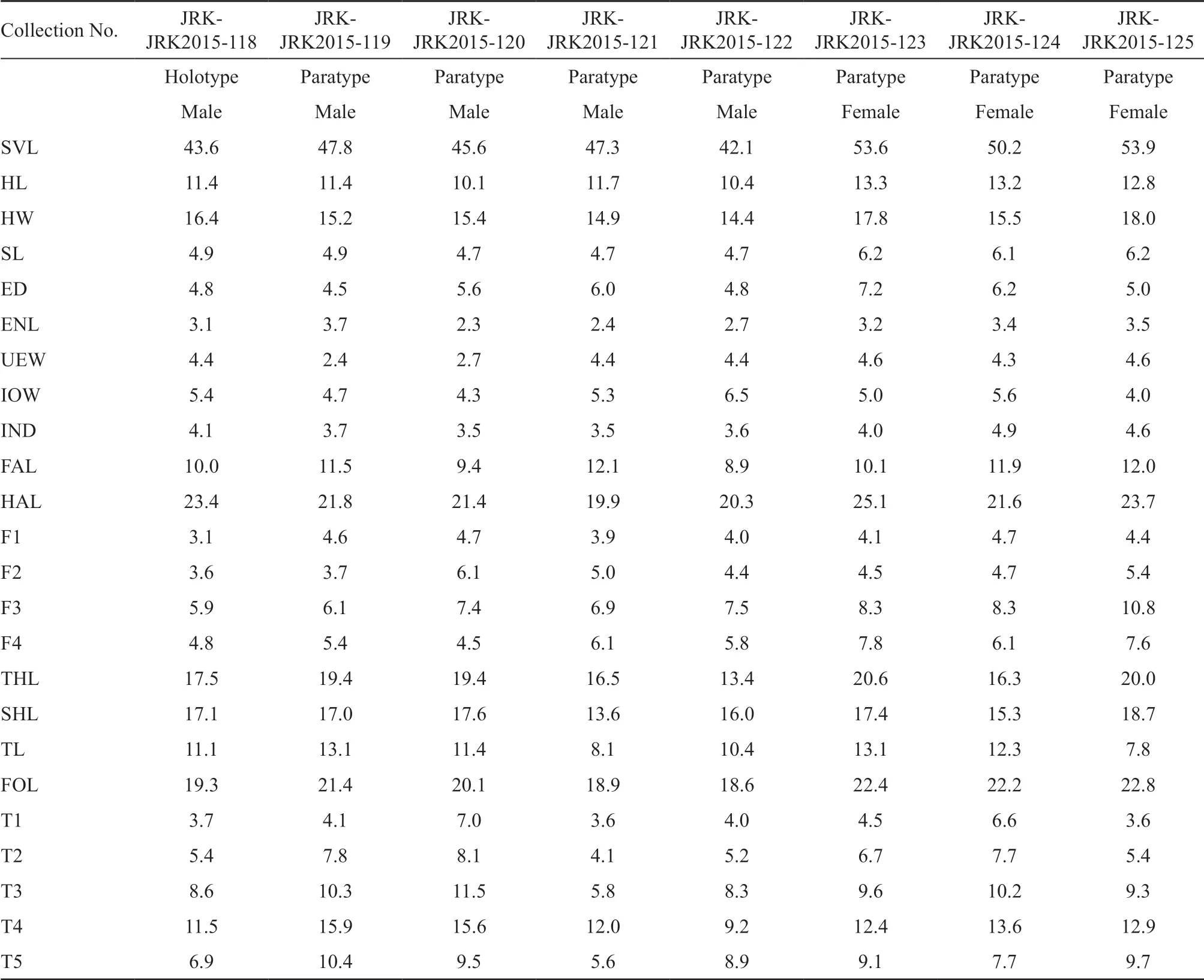

Variation and sexual dimorphism:Morphometric variation of type specimens is presented in Table 5. The female were significantly larger in SVL (t= -4.50,p= 0.006,df= 6), head width (t= 2.63,p= 0.039,df= 6), inter narial width (t= 2.74,p= 0.034,df= 6), 3rd finger (t= 3.18,p= 0.019,df= 6), and 4th finger (t= 3.21,p= 0.016,df= 6) than males. Males with nuptial spines on the dorsal surface of first three fingers (absent in females); a pair of pectoral and axillary glands present on chest (absent in females). Females with smooth skin, body surface devoid of spines; warts flatter on dorsal body surface than in males.

Eggs

A total of 14 eggs were collected while being guarded by a male under a rock. The eggs were rounded in shape and ranged from 3.4 to 4.2mm (Mean 3.9 ± SD 0.28, N = 14). The vegetal and animal poles were creamy in colour.

Larvae (all measurements in mm)

Thirteen tadpoles (identity confirmed by molecular analysis) from different stages were examined (Gosner 1960). The following description is based on Gosner stage 27 tadpole ofScutigerghunsasp. nov. In dorsal view, body oval, posterior part wider than the anterior part, total body length (N = 5, TL = 27.6-33.1), body length 33% of TL and tail length 66% of TL. Head oval and broad, snout rounded, eyes dorsolaterally set, nostrils oval, closer to snout (ENL 18% of BL, SN 11% of BL, SSD 56% of BL, IND 22% of BL and IOW 29% of BL) than to eye. Oral disc ventrally set; lips with papillae, one uninterrupted row of keratodonts (denticles) and two interrupted rows of keratodonts on upper labium. Lower labium comprising one uninterrupted keratodont row followed by two interrupted keratodont rows. Tooth row formula (Dubois 1995): 1:2+2/2+2:1 (Figure 7). Spiracle sinistral, single, midventral, posterodorsally directed; extended as a short tube, oval spiracular opening. Dextral vent tube opening at the margin of ventral fin. Intestinal coils visible. Tail musculature robust and greatly narrowing to tail tip; tail tip pointed; upper tail fin higher than lower tail fin, both fins converging at tip.

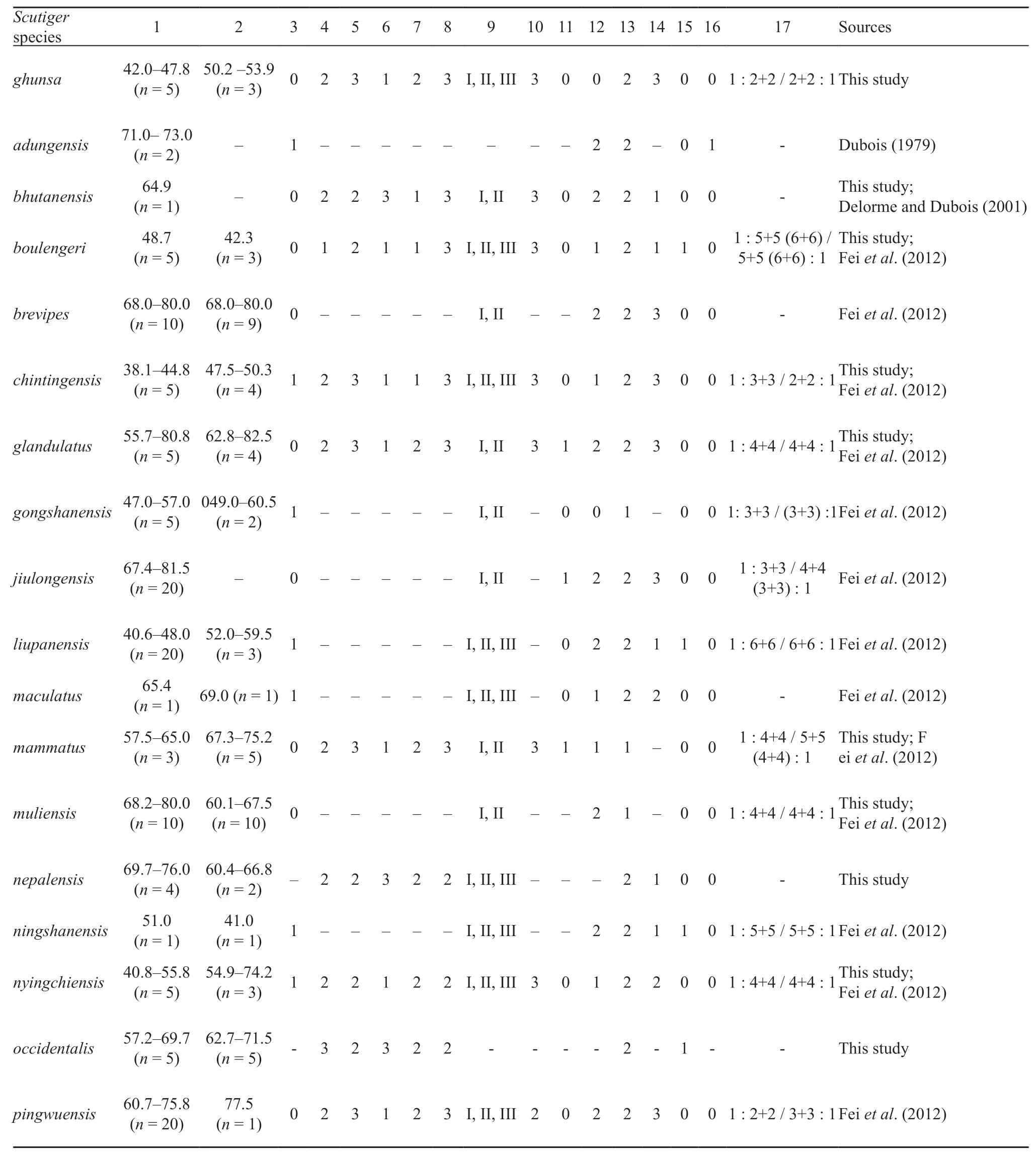

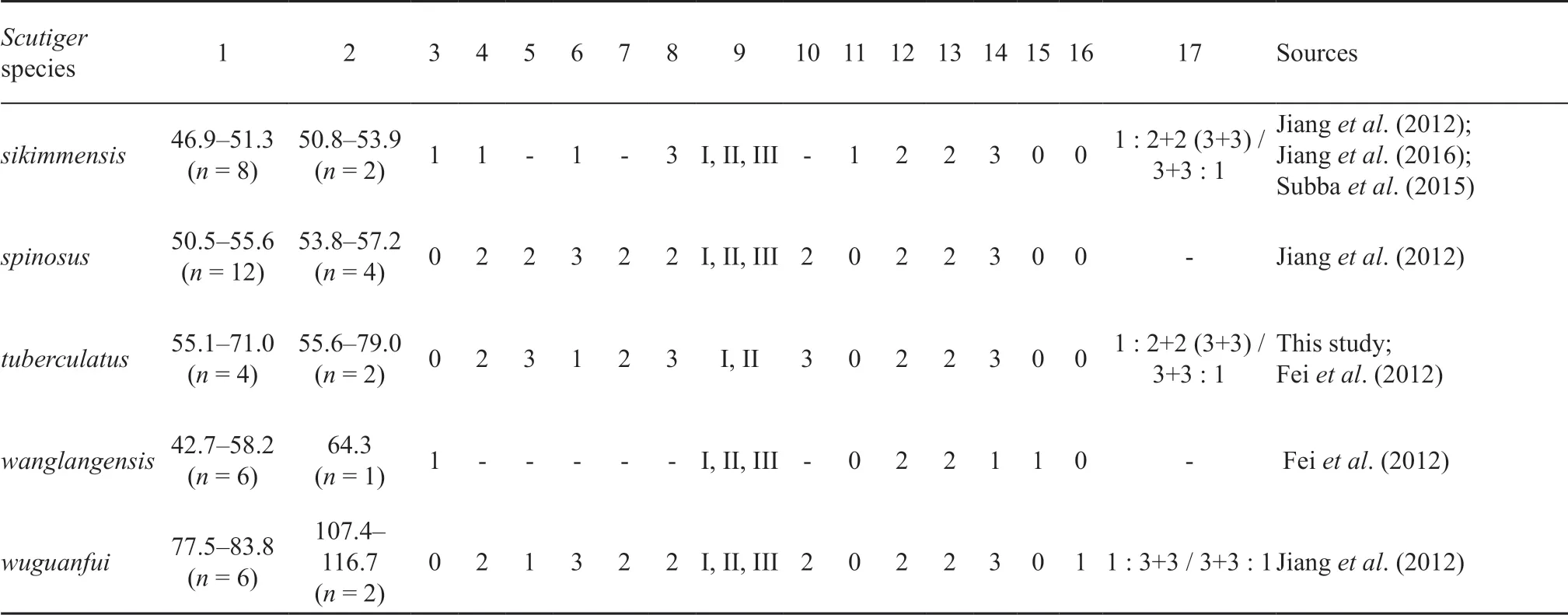

Table 4 Mensural and meristic data for adults and tadpole of Scutiger ghunsa sp. nov. compared with congeneric species. Morphological characters: 1. Male SVL (ranges with total number examined); 2. Female SVL (ranges with total number examined); 3. Maxillary teeth: (1) present, (0) absent; 4. Relative length of snout (SL/HL*100): (1) shorter than 20%, (2) between 20%-40%, (3) longer than 40% of HL; 5. Relative eye size (ED/HL*100): (1) shorter than 20%, (2) between 20%-40%, (3) longer than 40% of HL; 6. Interorbital distance (IOW/IND*100: (1) longer, (2) equal, (3) shorter than IND; 7. Length of arm (LA/SVL*100): (1) shorter than 20%, (2) between 20%-40%, (3) longer than 40% of SVL; 8. Length of hand (LA/SVL*100): (1) shorter than 20%, (2) between 20%-40%, (3) longer than 40% of SVL; 9. Number of fingers with nuptial spines: (1) presence in first three fingers (I, II, III), (2) first two fingers (I, II); 10. Inner metatarsal tubercle: (1) longer than first toe, (2) equal, (3) 50% less or shorter; 11. Subarticular tubercles: (1) present, (0) absent; 12. Toes webbing: (1) webbed, (2) weakly webbed, (0) absent; 13. Number of pectoral and axillary glands: (1) one, (2) two; 14: Size of pectoral and axillary glands: (1) pectoral and axillary glands same size, (2) pectoral glands slightly larger than axillary glands, (3) pectoral glands two time or even larger than axillary glands; 15. Spines on belly in males: (1) present, (0) absent; 16. Vocal sacs: (1) present (0) absent; 17. Keratodont row formulae in tadpole.

(Continued Table 4)

Coloration in preservative

The dorsal and lateral surfaces of the head, body and tail region are dark brown. The abdomen is dark brown and transparent, with clearly visible intestine coils; the ventral surface of tail creamy white.

Comparisons

Scutigerghunsasp. nov. is morphologically distinct from otherScutigerspecies found in Nepal and nearby regions by the following qualitative characters. The characters ofScutigerghunsasp. nov. are presented in parentheses; see also Table 4 and Appendix 1.

Scutiger adungensis(Dubois, 1979), (distribution: only known from Adung valley of Myanmar) large sized (vs. medium sized), maxillary teeth present (vs. absent), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), vocal sacs present (vs. absent).

Scutiger bhutanensis(Delorme and Dubois, 2001), (distribution: Bhutan type locality unknown), large sized (vs. medium sized), maxillary teeth present (vs. absent), toes webbing weakly webbed (vs. absent), vocal sacs present (vs. absent), eye diameter larger than 20% of HL (vs. between 20-40% HL), interorbital distance shorter than IND (vs. longer), length of arm shorter than 20% of SVL (vs. between 20-40%), nuptial spines in breeding male on first two fingers (vs. presence in first three fingers), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), vocal sacs present (vs. absent), pectoral and axillary glands similar in size (vs. two times larger).

Scutiger boulengeri(Bedriaga, 1898), (Distribution: western Nepal, Sikkim, India, and southern Tibet to Sichuan, Yunnan, Gansu, and Qinghai, China, 3300-5270 m elevation), female body size smaller (vs. medium size), snout shorter than 20% of HL (vs. between 20%-40% of HL), toes webbing weakly webbed (vs. absent), pectoral and axillary glands similar in size (vs. two times larger), spines on belly in breeding males (vs. absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1:5+5(6+6)/5+5(6+6):1).

Figure 7 Mouth parts of tadpole of Scutiger ghunsa sp. nov. showing labial teeth.

Table 5 Measurements (mm) of the onomatophores of Scutiger ghunsa sp. nov. from Ghunsa, Taplejung, Nepal.

Scutiger brevipes(Liu, 1950), (distribution: Taining, Daofu County, Sichuan, China), large sized (vs. medium sized), nuptial spines on breeding male on first two fingers (vs. present on first three fingers), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent).

Scutiger chintingensis(Liu and Hu, 1960), (distribution: Emei Mountain region, Hongya and Wenchuan counties, Sichuan, China), maxillary teeth present (vs. absent), arm shorter than 20% of SVL (vs. between 20-40%), toes webbed (vs. webbing absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1:3+3/2+2:1).

Scutiger glandulatus(Liu, 1950) (distribution: Northern Yunnan, western Sichuan and southern Gansu, China.), large sized (vs. medium sized), nuptial spines in breeding male on first two fingers (vs. presence on first three fingers), presence subarticular tubercles (vs. absent), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1:4+4/4+4:1).

Scutiger gongshanensis(Yang and Su, 1979) (distribution: Gongshan and Biluoxshan in Yunnan, China), presence of maxillary teeth (vs. absent), nuptial spines in breeding males on first two fingers (vs. presence on first three fingers), a single pectoral gland in breeding male (vs. two), tadpole keratodont formula (1:3+3/3+3:1).

Scutiger jiulongensis(Fei, Ye, Cand Jiang, 1995) (distribution: Tanggu, Juilong County, Sichuan, China), large sized (vs. medium sized), nuptial spines in breeding males on first two fingers (vs. presence on first three fingers), subarticular tubercles present (vs. absent), toes webbed (vs. absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1:3+3/ 4+4(3+3):1).

Scutiger liupanensis(Huang, 1985), (distribution: Liupanshan, Jingyuan County, Ningxiz Huiza Zizhiqu Autonomous Region, China), presence of maxillary teeth (vs. absent), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), pectoral and axillary glands similar in size (vs. two times larger), spines on belly in breeding males (vs. absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1:6+6/6+6:1).

Scutiger maculatus(Liu, 1950), (distribution: Garza County, Sichuan, and Jiangda, Tibet, China), large body size (vs. medium size), maxillary teeth present (vs. absent), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), pectoral and axillary glands similar in size (vs. two times larger).

Scutiger mammatus(Günther, 1896), (distribution: Eastern Tibet, Qinghai and Sichuan, China), body large sized (vs. medium sized), nuptial spines in breeding males on first two fingers (vs. presence on first three fingers), presence of subarticular tubercles (vs. absent), toes webbed (vs. absent), a single pectoral gland in breeding male (vs. two), tadpole keratodont formula (1:4+4/5+5 (4+4):1).

Scutiger muliensis(Fei and Ye, 1986), (distribution: Muli County, Sichuan, China), body large sized (vs. medium sized), nuptial spines in breeding males on first two fingers (vs. present on first three fingers), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), a single pectoral gland in breeding males (vs. two), tadpole keratodont formula (1:4+4/4+4:1).

Scutiger nepalensis(Dubois, 1974), (distribution: Khaptad, western Nepal), body large sized (vs. medium sized), eye diameter larger than 20% of HL (vs. between 20-40% HL), interorbital distance shorter than IND (vs. longer), length of arm shorter than 20% of SVL (vs. larger than 40% of SVL), pectoral and axillary glands similar in size (vs. pectoral gland two times larger).

Scutiger ningshanensis(Fang, 1985), (distribution: Ningshan County in southern Shaanxi Province, China), maxillary teeth present (vs. absent), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), pectoral and axillary glands similar in size (vs. pectoral gland two time larger), spines on belly in breeding males (vs. absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1:5+5/5+5:1)

Scutiger nyingchiensis(Fei, 1977), (distribution: Western Nepal, Kashmir, Ladakh, and Tibet, China), large body size (vs. medium size), presence of maxillary teeth (vs. absent), eye diameter larger than 20% of HL (vs. between 20-40% of HL), toes webbed (vs. absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1:4+4/4+4:1).

Scutiger occidentalis(Dubois, 1978) (distribution: Jammu Kashmir, India), large body size (vs. medium size), snout shorter than 20% of HL (vs. between 20-40% of HL), eye diameter larger than 20% of HL (vs. between 20-40% of HL), interorbital distance shorter than IND (vs. longer), length of hand shorter than 20% of SVL (vs. between 20-40% of SVL).

Scutiger pingwuensis(Liu, Hu, and Tian, 1978), (distribution: Pingwu County, Sichuan, China), large body size (vs. medium size), length of inner metatarsal tubercle equal to first toe length (vs. less than 50% or shorter), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1:5+5/3+3:1).

Scutiger sikimmensis(Blyth, 1854), (distribution: Sikkim and Meghalaya (India), Bhutan and southern Tibet, China), maxillary teeth present (vs. absent), snout length shorter than 20% of HL (vs. between 20-40%), subarticular tubercles present (vs. absent), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1:2+2(3+3)/3+3:1).

Scutiger spinosus(Jiang, Wang, Zou, Yan, Li and Che, 2016) (distribution: Medog, Tibet, China), body large sized (vs. medium sized), eye diameter larger than 20% of HL (vs. between -40% of HL), interorbital distance shorter than IND (vs. longer), length of hand between 20-40% of SVL (vs. longer than 40% of SVL), inner metatarsal tubercle equal length of first toe (vs. less than 50% or shorter), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent).

Scutiger tuberculatus(Liuet al., 1979), (distribution: Southern Sichuan and north-central Yunnan, China), body large sized (vs. medium sized), nuptial spines in breeding males on first two fingers (vs. presence on first three fingers), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1: 2+2(3+3)/3+3:1).

Scutiger wanglangensis(Ye and Fei, 2007), (distribution: Pingwu and Nanping counties, Sichuan, China), body large sized (vs. medium sized), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), pectoral and axillary glands similar in size (vs. pectoral gland two times larger), spines on belly in breeding males (vs. absent).

Scutiger wuguanfui(Jiang, Rao, Yuan, Li, Hou, Chen and Che, 2012) (distribution: Medog, Muotuo County, Xizang, China), body large sized (vs. medium sized), eye diameter larger than 20% of HL (vs. between 20%-40% of HL), interorbital distance shorter than IND (vs. longer), length of hand between 20%-40% of SVL (vs. longer than 40% of SVL), inner metatarsal tubercle equal to length of first toe (vs. less than 50% of first toe or shorter), toes weakly webbed (vs. absent), vocal sacs present (vs. absent), tadpole keratodont formula (1:3+3/3+3:1).

Distribution and natural history

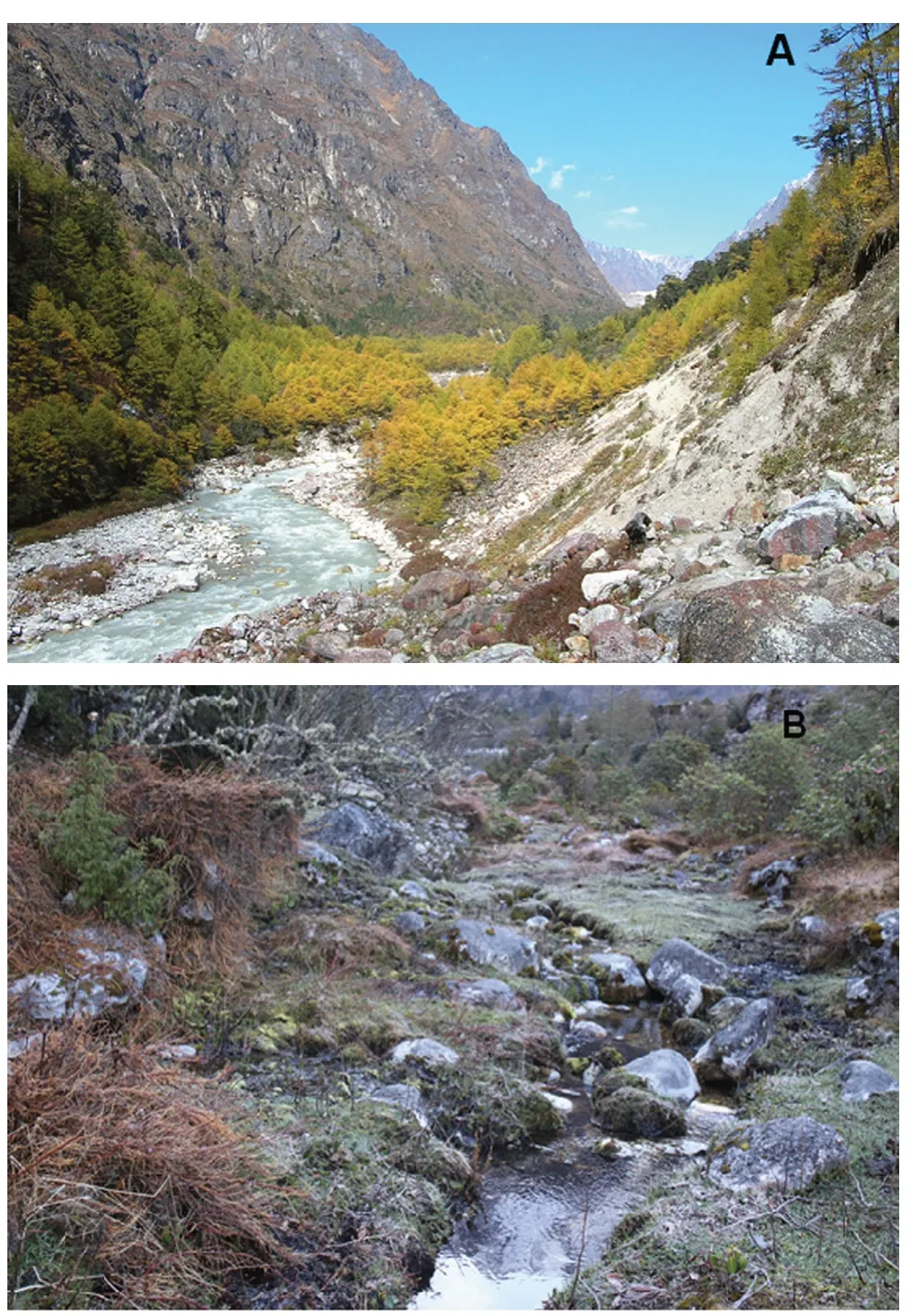

Scutiger ghunsasp. nov. is currently known only from the type locality (Figure 8) and could not be found at several localities from Makalu Barun National Park and Kanchenjunga Conservation Area in the eastern Nepal. The new species was recorded from a mixed rhododendron forest with low canopy cover with a slowrunning stream and stagnant water pools. We encountered only five specimens at night, hiding on boulders and in rock crevices. We found an adult male with clutches on its back hidden in the rock crevices. Some frogs are known to guard egg clutches (Zhenget al., 2011), however, parental care in the genusScutigerhas not been reported so far. But, we have no further evidence to confirm if this behaviour was accidental or if it can be considered parental care.

Tadpoles were free moving and were highly photosensitive at night. They usually take refuge in rock crevices and vegetation when a torch light is pointed at them. The water was clear, and soil was acidic (pH 5.4) in the habitat. No calls were heard. Type locality lies inside the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area, in a semiforested part, near a human trail and Ghunsa Khola. Therefore, considering the lack of comprehensive records of populations of the new species, we suggest that the Red List category ofScutiger ghunsasp. nov. is Data Deficient according to IUCN (2001) guidelines.

4. Discussion

More than 57% (12 out of 21) of known species ofScutigeroccur at the edge of the Sichuan basin in western China and many of them are reported only from their type-locality (Feiet al., 2012). Recently, the genusScutigerhas been divided in to three major groups: the greater Himalayan, Tsinling Mountaing and Sichuan Basin, and the Tibet and Hengduan Mountain regions based on molecular phylogenetic analysis (Hofmannet al., 2017).Scutigerspecies that are distributed on the southern slope of the Himalaya belongs to the greater Himalayan species (S. nepalensis,S. sikkimensis,S. occidentalis, andS. ghunsasp. nov.). Our molecular results suggested thatS. nepalensisis the closest congener to the new species; this species is distributed at elevations of 2700-4500 in western Nepal.Scutiger ghunsasp. nov showed substantial differentiation fromS. nepalensisin both morphological and molecular analysis. Among the knownScutigerspecies,S. sikkimensisoccurs in closest proximity to the new species and is distributed in the Dudh Koshi and Arun rivers approximately 40-60 km west from the type locality ofS. ghunsasp. nov. However, their ranges are greatly separated from each other by steep river gorges and mountains. This study identified three distinct divergent lineages ofS. sikkimensis, two of them are from Dhudh Koshi and Arun River, Nepal and one from Yadong, Tibet, China. There was substantially low genetic divergence in 16S gene betweenS. sikkimensisfrom Sikkim, India and Dhudh Koshi and Arun River, Nepal. Due to high genetic divergence that exists in this species group, further study is required on these two populations from Yadong, China and Surkie La, Dudhkoshi River (west) to solve the current taxonomic ambiguities.

Figure 8 A. Habitat and B. microhabitat of Scutiger ghunsa sp. nov. at Kanchenjunga Conservation Area, Taplejung district, Ghunsa valley, Nepal.

This study found thatS. boulengeriis distributed widely to the alpine desert across the Tibetan plateau of China, India (Sikkim) and Nepal (Mustang). However, previous studies suggested thatS. boulengeriis a paraphyletic species complex with a high rate of mitochondrial gene introgression following hybridization (Chenet al., 2009). The molecular phylogeny of the genusScutigerindicated that this group appears to have highly conserved morphological characters and suggests the presence of many many cryptic species (Hofmannet al., 2017). Of the currently recognized species ofScutiger,S. bhutanensisandS. adungensisare geographically closer toScutiger ghunsasp. nov.Scutiger bhutanensisis known from the imprecise type locality from Bhutan, without any habitat and other geographical characteristics (Delorme and Dubois 2001). The second species,S. adungensis,from Adung Valley of Myanmar near to China, boarder at 3,650 m, is also reported from a single locality.

Previously, four species ofScutigerwere reported from Nepal based on external morphology (Dubois 1974; 1987; Nanhoe and Ouboter 1987). Past studies were limited by several factors such as limited sampling in restricted geographic areas or limited species included in the morphological comparisons. In recent years, several cryptic taxa have been identified based on molecular methods. For example, Hofmannet al., (2017) reported highly divergent lineages ofS. nepalensisandS. sikkimensisfrom western and eastern Nepal Himalayas that might be a potential new species. In the framework of an integrative taxonomic approach (Dayrat 2005; Schlick-Steineret al., 2010) to describe biodiversity and understand the diversification ofScutigeracross the Himalayan range, not only is further fieldwork needed throughout the range, but diverse approaches (morphological studies including historical specimens, in particular types, behavioral studies, specially analyses of mating calls and mating behavior, or cytology) should be used in combination with molecular studies. In recent publications of the amphibians of the eastern Himalayas of Nepal, two new species of amphibians,Tylototriton himalayanus(Khatiwadaet al., 2015) andMicrohyla taraiensis(Khatiwadaet al., 2017) were identified, indicating the presence of several unrecognized cryptic species. With the addition ofScutiger ghunsasp. nov. the genusScutigernow contains 24 species with 5 in Nepal. The description of a new species highlights the still poor knowledge of amphibians in the area and points to the possibility of the existence of more cryptic taxa. BecauseScutiger ghunsasp. nov. is currently known only from type locality, efforts are needed to find additional populations of the new species and assess its conservation status.

AcknowledgementsWe are thankful to Subarna Ghimire, Bibas Shrestha and Purnaman Shrestha for their assistance during field work. We are thankful to Urs Wüest, Naturhistorisches Museum Basel, Switzerland for the information on the holotype ofScutiger bhutanensis. We are grateful to Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC) for providing necessary research permit for amphibian study in the Nepal Himalaya. We are thankful to Wang Xiaoyi (Chengdu Institute of Biology) for providing tissue samples ofS. boulengerifrom Zhiduo and Zhaduo, Qinghai, China. This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA23080101) and National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (NSFC-31471964) grants to Jianping Jiang and the second comprehensive science investigation of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (QTP) (II08-T05-2017-04/06). In addition, JRK was supported by the CAS-TWAS President Fellowship and Chinese Academy of Sciences President’s International Fellowship Initiative (2018PB0016).

杂志排行

Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- Mitochondrial Diversity and Phylogeographic Patterns of Gekko gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae) in Thailand

- Molecular Cloning and Putative Functions of KIFC1 for Acrosome Formation and Nuclear Reshaping during Spermiogenesis in Schlegel’s Japanese Gecko Gekko japonicus

- Altitudinal Variation in Digestive Tract Lengh in Feirana quadranus

- Thermal-physiological Strategies Underlying the Sympatric Occurrence of Three Desert Lizard Species

- The Marking Technology in Motion Capture for the Complex Locomotor Behavior of Flexible Small Animals (Gekko gecko)