Molecular Cloning and Putative Functions of KIFC1 for Acrosome Formation and Nuclear Reshaping during Spermiogenesis in Schlegel’s Japanese Gecko Gekko japonicus

2019-09-27ShuangliHAOLiyueZHANGJunPINGXiaowenWUJianraoHUandYongpuZHANG

Shuangli HAO, Liyue ZHANG, Jun PING, Xiaowen WU, Jianrao HU and Yongpu ZHANG*

1 College of Life and Environmental Sciences, Wenzhou University, Wenzhou 325035, China

2 College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China

3 College of Life and Environmental Sciences, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou 310036, China

Abstract Spermiogenesis, occurring in the male testis, is a complicated and highly-ordered developmental process resulting in the production of fertile mature sperm. In Gekko japonicus, this process occurs in 7 steps during which the spermatids undergo dramatic changes in the cytoskeleton and nucleus. Here, we cloned and sequenced the cDNA of the mammalian KIFC1 homologue in the testis of G. japonicus. The 2 344 bp full-length cDNA sequence contained a 191 bp 5'-untranslated region, a 134 bp 3'-untranslated region and a 2 019 bp open reading frame encoding a protein of 672 amino acids. Tissue expression analysis revealed the highest expression of kifc1 mRNA was in the testis. Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed that the kifc1 mRNA signal was hardly detected in step 1 spermatids but became concentrated at the acrosome of step 2 spermatids and abundant in the nucleus of step 5 spermatids where the nucleus then undergoes dramatic elongation and compression. The kifc1 mRNA signal then gradually disappears in mature sperm. This expression of KIFC1 at specific stages of spermiogenesis in G. japonicus implies its important role in the major cytological transformations such as acrosome biogenesis and nucleus morphogenesis.

Keywords Spermiogenesis, KIFC1, Kinesin, Gekko japonicus

1. Introduction

The production of sperm capable of fertilization is a primary factor for the survival of reptile species just as it is for mammals. Spermatogenesis is a complicated and highly-ordered developmental process occurring in the male testis. It begins with spermatogonia proliferation and differentiation, which includes mitosis and meiosis, and eventually terminates in the process of spermiogenesis with the dramatic morphological and cellular changes and the differentiation of haploid spermatids towards highly condensed mature spermatozoa that this process

represents (Hess and Renato, 2008; Gribbins, 2011). Among all the cytological changes of this process there are three particularly significant biological events that occur, biogenesis of the acrosome, morphogenesis of the nucleus, and formation of the sperm tail (Wang and Sperry, 2008; Hermoet al., 2010). The acrosome begins with the formation of proacrosomal vesicles that themselves have their origins in many Golgi vesicles. These proacrosomal vesicles gradually adhere to the nuclei, expand to cover the major spermatid nucleus and finally form the acrosome as the most visible organelle at the apical surface of spermatid nucleus (Morenoet al., 2000). As it a specialized lysosome-like organelle containing hydrolytic enzymes, the formation of a functional acrosome is indispensable towards the intended penetration of the oocyte (Yoshinaga and Toshimori, 2003). The normal morphogenesis of the nucleus of the mature sperm is appropriately streamlined and includes a high amount of condensation which is crucial for accommodating paternal genetic material and ensuring fertilization capability (Wanget al., 2010a). Many researchers have proposed that the function of manchette, a structure that primarily consists of microtubules and microtubule-associated proteins, occurs as a direct result from these nuclear condensation and elongation processes (Wanget al., 2010a, 2010b).

Increasing evidence suggests that a network of cytoskeletal and molecular motors are essential participants in the process of spermiogenesis. These motors include actin-associated myosin, microtubuleassociated kinesin and dynein (Chennathukuzhiet al., 2003; Vaidet al., 2007) and they also play amazing biological roles in many aspects of cellular movement, such as organelle and vesicle transport (Shea and Flanagan, 2001), cell and cilia movement (Karkiet al., 2002; Nonakaet al., 2002), and cell division (Navolanic and Sperry, 2000). Some motor proteins may even have roles in cellular architecture (Helfandet al., 2002), basic developmental processes (Nonakaet al., 2002) and in the processes of many diseases (Qinet al., 2001; Watterset al., 2001). Relating specifically to the process of spermiogenesis, it has been reported that some specific molecular motor proteins play crucial roles. These include the action of the movement of spermatids, formation of the manchette and the spindle, reshaping of the nuclear and the formation of the acrosome (Navolanic and Sperry, 2000; Zouet al., 2002; Wang and Yang, 2010; Wanget al., 2010a, 2010b, 2010c, 2012; Danget al., 2012; Huet al., 2012).

Kinesin is a superfamily of motor proteins that walk along microtubules and act to sort and transport various cellular cargoes to a range of destinations (Kikkawa, 2008; Hirokawaet al., 2009). Many kinesin members have been identified from testis and these are suggested to have roles in multiple cellular aspects of spermatogenesis (Zouet al., 2002). KIFC1 belongs to the kinesin-14 subfamily, a group of highly related C-terminal motor proteins with divergent tail domains (Mountainet al., 1999). During rat spermiogenesis, KIFC1 is involved in the transport of proacrosomal vesicles from the Golgi apparatus to the forming acrosome (Yang, 2007). Whilst moving along manchette microtubules, this protein also associates with a nuclear pore protein-containing complex on the nuclear envelope and contributes to the generation and transmission of the force needed for the shaping of the nucleus (Yanget al., 2006). However, whether and how a motor protein like KIFC1 is associated with acrosome formation in reptiles and whether it participates in a similar nuclear shaping in reptiles as it does in rodents remains unknown. Elucidation of such functional mechanism in reptiles would provide important clues concerning the evolution of the biogenesis of the acrosome and of sperm nuclear shaping machinery.

This article describes the process of spermiogenesis from a sub-cellular level and provides a prediction of the role of the molecular motor KIFC1 in this process. The small, oviparous and nocturnal squamata species,Gekko japonicus,is the model animal in this study. It belongs to Reptilia: Squamata: Lacertilia: Gekkonidae:Gekko. Our initial hypothesis was that the KIFC1 ofG. japonicuswould also participate in acrosome formation and nuclear shaping process during spermiogenesis, either directly or indirectly. In this study, we detected the presence of thekifc1mRNA from the testis of Gekkotan reptile for the first time and provided clear observations of the dynamic localization of spermiogenic cells at different stages. Based on these results, we suggest functional models of KIFC1 with respect to the formation of acrosome and morphogenesis of nucleus inG. japonicus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and tissue preparation13 adultG. japonicusmales were captured in Wenzhou (27°23' N, 119°37' E), Zhejiang Province, China in May 2015. Among these animals, 5 adult males were quickly sacrificed and dissected to collect the heart, liver, muscle, testis and epididymis for total RNA extraction. The remaining 8 mature males were divided into two parts randomly and from which only testes were taken for fluorescencein situhybridization (FISH) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations. Testis tissues for FISH were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 Mol/L, pH 7.4) for 2 h. They were then dehydrated in 20% sucrose solution in PBS for 4 h and embedded with O.C.T. and transferred in -80°C for frozen section.

2.2. Transmission electron microscopyThe testes for TEM were cut into 1-2 mm3pieces and treated with a solution containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde and 3% sucrose in a 0.1 Mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) at 4°C overnight. They were then rinsed in 0.1 Mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), postfixed in buffered 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h, washed in 0.1 Mol/L phosphate buffer, dehydrated in a series of ascending contents of acetone (70%-100%) and finally embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were stained in lead citrate, 6% aqueous uranyl acetate and again in lead citrate successively. Electron micrographs were then taken using a Hitachi 7500 TEM.

2.3. RNA extraction and reverse transcriptionTotal RNA from the heart, liver, muscle, testis, and epididymis were extracted with Trizol reagent (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacture’s instructions. All samples were ground using a homogenizer with Trizol reagent and then treated with chloroform, isopropanol and 75% ethanol sequentially to obtain precipitated RNA. The precipitated RNA from each tissue was dissolved in 100 μl DEPC-H2O and its concentration determined using the spectrophotometrical method by micro-spectrophotometer (Nano-100, Allsheng). Reverse transcription was conducted using a PrimeScript® RT reagent Kit (Takara, Dalian, China). The cDNA obtained from the testis was used forkifc1gene cloning and all samples were stored at -40°C for real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR analysis ofkifc1mRNA expression in different tissues.

2.4. Degenerate primer designWe aligned the KIFC1 homology proteins downloaded from NCBI, taken from varied species ranging from protozoa to mammals, by ClustalW and many conserved regions of amino acid residues were obtained. Based on those conserved regions, we designed six degenerate primers named F1, F2, F3, F4, R1 and R2 (Table 1) using CODEHOP online software (http://bioinformatics.weizmann.ac.il/blocks/codehop.html). We registered these primer sequences at the Shanghai Sangon Biological Engineering Technology Company for synthesis

2.5. Cloning of kifc1 cDNA fragmentsA cDNA fragment ofkifc1was amplified with the degenerate primer pairs F1/R1, and F2/R2 using a Mygene Series Peltier Thermal Cycler (Hangzhou, China) and the Nested Touchdown PCR with the program run as follows: 94°C for 5 min, 10 cycles of the touchdown program (94°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min, followed by 0.5°C decrease of the annealing temperature per cycle), followed by 30 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min) with 10 min at 72°C for the final extension. The PCR products were then examined and separated by agarose electrophoresis where DNA gel green was added for the visualization of the electrophoretic band position. The expected product was extracted and purified by AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen) and AxyPrep PCR Cleanup Kit (Axygen). Eventually, the purified fragment we obtained was linked into PMD19-T-vectors (Takara), propagated inEscherichia coli DH5α(Takara) and then sent to the Sangon Biological Engineering Technology Company for sequencing. Based on this determined fragment, we designed two reverse primers (R3 and R4) (Table 1) using the Primer Premier 5 software and performed another Nested Touchdown PCR with F3 and F4 to extend the determined sequence from 5' cDNA end.

2.6. Rapid-amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)To get the full length cDNA ofkifc1, we performed rapid amplification of cDNA ends utilizing 3'-Full RACE Core Set with PrimeScript™ Rtase (Takara) and Smart RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech) in accordance with the kit instructions. Specific primers for both 3' (F'1 and F'2) and 5' RACE (R'1 and R'2) (Table 1) were designed using Primer Premier 5 software. The PCR programs for 3' and 5' RACE were run as follows: 94°C for 5 min, 10 cycles of touchdown program (94°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s, 72°C for 40 s, followed by 0.5°C decrease of the annealing temperature per cycle), followed by 30 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 40 s) with 10 min at 72°C for the final extension; 94°C for 5 min, 10 cycles of touchdown program (94°C for 30 s, 70°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min, followed by a 0.5°C decrease of the annealing temperature per cycle), followed by 30 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min) with 10 min at 72°C for the final extension, respectively.

Table 1 All primers used in the experiments.

2.7. Sequence analysis and alignment and phylogenetic analysisThe full length of thekifc1cDNA sequence was checked and assembled using the program Seqman (DNASTAR, Inc.). The amino acid sequence was translated by the online ExPASy translate tool (http://web.expasy.org/translate/). Both DNA sequence and deduced amino acid sequence were examined for similarities with known sequences in the non-redundant GenBank database by BLAST online in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Multiple sequence alignments were performed with Vector NTI10 (Invitrogen). The secondary structure of the KIFC1 protein was predicted with the ExPASy Molecular Biology Server (http://expasy.pku.edu.cn). The 3-D structure of KIFC1 was predicted with an online server I-TASSER (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER) (Yang, 2007; Ambrishet al., 2010). The phylogenetic tree, neighbor-joining (NJ) method, was constructed according to the deduced amino acid sequence using MEGA version 5.0.

2.8. Real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR analysis ofkifc1mRNA expression in different tissuesA pair of primers (qF2, qR2) (Table 1) were designed for analyzing the expression ofkifc1mRNA in the tissues: heart, liver, muscle, testis, and epididymis. A pair of primers (q-actin-F3, q-actin-R3) (Table 1) was used to amplify a β-actin cDNA fragment as the control. This experiment was performed using the SYBR Premix ExTaqTMII kit (Takara) according to the kit instructions. The PCR program was run as follows: initial incubation at 95°C for 30 s; 40 cycles in a normal program: 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 30 s. The data analysis ofkifc1mRNA expression in different tissues was using the Ct value comparison method (2-ΔΔCt).

2.9. FISH and confocal microscopyThe testes for FISH were removed from -80°C and cut into 7 μm sections at -24°C. The tissue sections were then quickly restored at -80°C for later experiments. A reverse primer (Probe-R) was designed from the 5' end, then synthesized and 5'-FAM added by Shanghai Generay Biotech Co, Ltd to make it a fluorescence probe.

The tissue sections were positioned at room temperature with aseptic and RNAse-free conditions for drying for 10 min and then treated with 4% PFA (pH 7.4) for another 10 min. We then rinsed tissue sections with 0.1% DEPC-activated 0.1 Mol/L PBS (pH 7.4) at room temperature twice for 10 min for each. The sections were then treated with PBSTx (PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100) for tissue permeabilization for 30 min. For each experimental section, 150 μl hybridization buffer was added while equal amounts of PBS were added to the control sections. These were all placed into a humidity chamber in the dark for 2 h at 37°C. The concentration of the hybridization buffer was 1 μMol/L. Subsequently, all sections were washed 3 times in PBS for 30 min. DAPI (Beyotime, Dalian, China) was used to counterstain the nuclei. Finally, we mounted the sections in Antifade Mounting Medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories) and sealed them with nail polish. The sections were observed and photographed using a Confocal Laser-scanning Microscope (CLSM510; Carl Zeiss, Germany).

3. Results

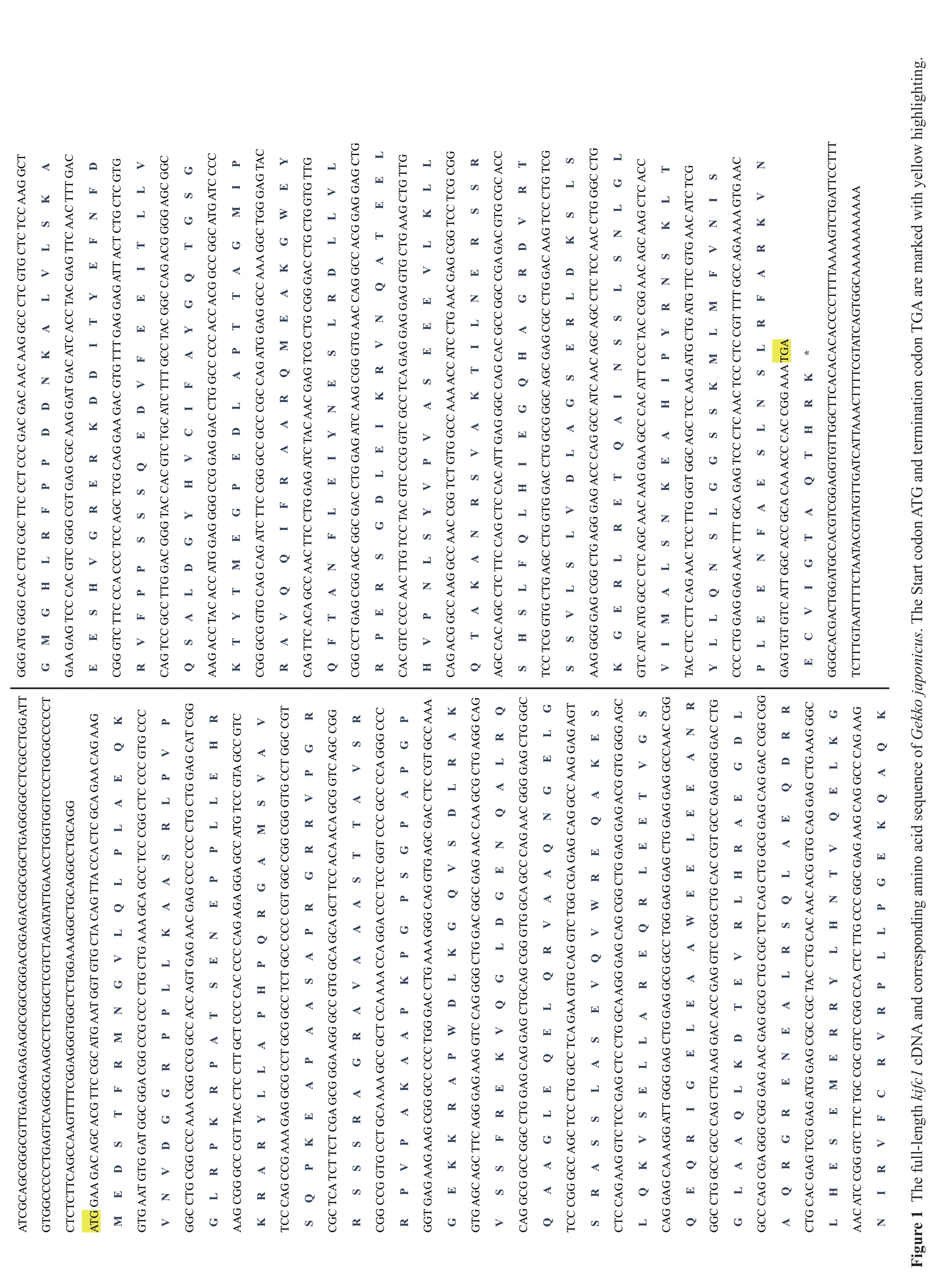

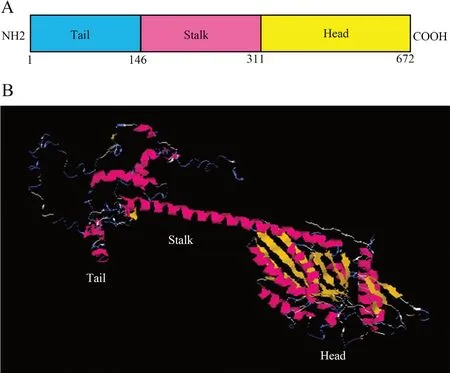

3.1.Kifc1sequence and phylogenetic analysisA 928 bpkifc1cDNA fragment was assembled by two small segments amplified from five degenerate primers F1, F2, F3, R1, R2 and a specific primer R3. A 1 389 bp 5' end cDNA and a 342 bp 3' end cDNA fragments were obtained through RACE. All four fragments made up a 2344 bpkifc1cDNA in length (GenBank accession number: KX129918) comprising of 191 bp of 5' UTR, a 134 bp of 3' UTR and a 2019 bp of open reading frame (ORF) (Figure 1) which was translated into a 672 amino acid (aa) with a predicated molecular mass about 74.5 kDa and an isoelectric point of 9.32 (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/). The putative KIFC1 homologues in different species shared microtubule binding sites, KIFC conserved consensus sequences and ATP binding sites. Secondary structure prediction showed that the KIFC1 ofG. japonicushad three primary domains: a divergent tail (1-220 aa) at the amino terminal, an ahelical stalk (221-388 aa) and a head (389-775 aa) at the carboxyl terminal (Figure 2A). The 3-D structure prediction showed that this protein shared extensive homology with C-kinesin structures, having a globular head domain, a central coiled-coil stalk domain and a fan-like tail (Figure 2B).

GGG ATG GGG CAC CTG CGC TTC CCT CCC GAC GAC AAC AAG GCC CTC GTG CTC TCC AAG GCT G M G H L R F P P D D N K A L V L S K A GAA GAG TCC CAC GTC GGG CGT GAG CGC AAG GAT GAC ATC ACC TAC GAG TTC AAC TTT GAC E E S H V G R E R K D D I T Y E F N F D CGG GTC TTC CCA CCC TCC AGC TCG CAG GAA GAC GTG TTT GAG GAG ATT ACT CTG CTC GTG R V F P P S S S Q E D V F E E I T L L V CAG TCC GCC TTG GAC GGG TAC CAC GTC TGC ATC TTT GCC TAC GGC CAG ACG GGG AGC GGC Q S A L D G Y H V C I F A Y G Q T G S G AAG ACC TAC ACC ATG GAG GGG CCG GAG GAC CTG GCC CCC ACC ACG GCC GGC ATG ATC CCC K T Y T M E G P E D L A P T T A G M I P CGG GCG GTG CAG CAG ATC TTC CGG GCC GCC CGC CAG ATG GAG GCC AAA GGC TGG GAG TAC E Y R A V Q Q I F R A A R Q M E A K G W CAG TTC ACA GCC AAC TTC CTG GAG ATC TAC AAC GAG TCG CTG CGG GAC CTG CTG GTG TTG Q F T A N F L E I Y N E S L R D L L V L CGG CCT GAG CGG AGC GGC GAC CTG GAG ATC AAG CGG GTG AAC CAG GCC ACG GAG GAG CTG R P E R S G D L E I K R V N Q A T E E L CAC GTC CCC AAC TTG TCC TAC GTC CCG GTC GCC TCA GAG GAG GAG GTG CTG AAG CTG TTG H V P N L S Y V P V A S E E E V L K L L CAG ACG GCC AAG GCC AAC CGG TCT GTG GCC AAA ACC ATC CTG AAC GAG CGG TCC TCG CGG Q T A K A N R S V A K T I L N E R S S R AGC CAC AGC CTC TTC CAG CTC CAC ATT GAG GGC CAG CAC GCC GGC CGA GAC GTG CGC ACC S H S L F Q L H I E G Q H A G R D V R T TCC TCG GTG CTG AGC CTG GTG GAC CTG GCG GGC AGC GAG CGC CTG GAC AAG TCC CTG TCG S S V L S L V D L A G S E R L D K S L S AAG GGG GAG CGG CTG AGG GAG ACC CAG GCC ATC AAC AGC AGC CTC TCC AAC CTG GGC CTG K G E R L R E T Q A I N S S L S N L G L GTC ATC ATG GCC CTC AGC AAC AAG GAA GCC CAC ATT CCC TAC CGG AAC AGC AAG CTC ACC V I M A L S N K E A H I P Y R N S K L T TAC CTC CTT CAG AAC TCC TTG GGT GGC AGC TCC AAG ATG CTG ATG TTC GTG AAC ATC TCG Y L L Q N S L G G S S K M L M F V N I S CCC CTG GAG GAG AAC TTT GCA GAG TCC CTC AAC TCC CTC CGT TTT GCC AGA AAA GTG AAC P L E E N F A E S L N S L R F A R K V N GAG TGT GTC ATT GGC ACC GCA CAA ACC CAC CGG AAA TGA E C V I G T A Q T H R K * GGGCACGACTGGATGCCACGTCGGAGGTGTTGGCTTCACACACACCCCTTTTAAAAGTCTGATTCCTTT TCTTTGTAATTTTCTAATACGTATGTTGATCATTAAACTTTTCGTATCAGTGGCAAAAAAAAAAA ATCGCAGCGGGCGTTGAGGAGAGAGGCGGCGGGACGGAGACGGCGGCTGAGGGGCCTCGCCTGGATT GTGGCCCCCTGAGTCAGGCGAAGCCTCTGGCTCGTCTAGATATTGAACCTGGTGGTCCCTGCGCCCCCT CTCTCTTCAGCCAAGTTTTCGGAGGGTGGCTCTGGAAAGGCTGCAGGCCTGCAGG D L K G Q V S D L R A K R E Q A K E S E E L E E A N R ATG GAA GAC AGC ACG TTC CGC ATG AAT GGT GTG CTA CAG TTA CCA CTC GCA GAA CAG AAG M E D S T F R M N G V L Q L P L A E Q K GTG AAT GTG GAT GGC GGA CGG CCG CCC CTG CTG AAA GCA GCC TCC CGG CTC CCC GTG CCC V N V D G G R P P L L K A A S R L P V P GGC CTG CGG CCC AAA CGG CCG GCC ACC AGT GAG AAC GAG CCC CCC CTG CTG GAG CAT CGG G L R P K R P A T S E N E P P L L E H R AAG CGG GCC CGT TAC CTC CTT GCT CCC CAC CCC CAG AGA GGA GCC ATG TCC GTA GCC GTC K R A R Y L L A P H P Q R G A M S V A V TCC CAG CCG AAA GAG GCG CCT GCG GCC TCT GCC CCC CGT GGC CGG CGG GTG CCT GGC CGT S Q P K E A P A A S A P R G R R V P G R CGC TCA TCT TCT CGA GCG GGA AGG GCC GTG GCA GCA GCT TCC ACA ACA GCG GTC AGC CGG R S S S R A G R A V A A A S T T A V S R CGG CCG GTG CCT GCA AAA GCC GCT CCA AAA CCA GGA CCC TCC GGT CCC GCC CCA GGG CCC R P V P A K A A P K P G P S G P A P G P GGT GAG AAG AAG CGG GCC CCC TGG GAC CTG AAA GGG CAG GTG AGC GAC CTC CGT GCC AAA G E K K R A P W GTG AGC AGC TTC AGG GAG AAG GTC CAG GGG CTG GAC GGC GAG AAC CAA GCG CTG AGG CAG V S S F R E K V Q G L D G E N Q A L R Q CAG GCG GCC GGC CTG GAG CAG GAG CTGCAG CGG GTG GCA GCC CAG AAC GGG GAG CTG GGC Q A A G L E Q E L Q R V A A Q N G E L G TCC CGG GCC AGC TCC CTG GCC TCA GAA GTG CAG GTC TGG CGA GAG CAG GCC AAG GAG AGT S R A S S L A S E V Q V W CTC CAG AAG GTC TCC GAG CTC CTG GCA AGG GAG CAG CGG CTG GAG GAG ACG GTG GGG AGC L Q K V S E L L A R E Q R L E E T V G S CAG GAG CAA AGG ATT GGG GAG CTG GAG GCG GCC TGG GAG GAG CTG GAG GAG GCCAAC CGG Q E Q R I G E L E A A W GGC CTG GCC GCC CAG CTG AAG GAC ACC GAG GTC CGG CTG CAC CGT GCC GAG GGG GAC CTG G L A A Q L K D T E V R L H R A E G D L GCC CAG CGA GGG CGG GAG AAC GAG GCG CTG CGC TCT CAG CTG GCG GAG CAG GAC CGG CGG A Q R G R E N E A L R S Q L A E Q D R R CTG CAC GAG TCG GAG ATG GAG CGC CGC TAC CTG CAC AAC ACG GTG CAG GAG CTG AAG GGC L H E S E M E R R Y L H N T V Q E L K G AAC ATC CGG GTC TTC TGC CGC GTC CGG CCA CTC TTG CCC GGC GAG AAG CAG GCC CAG AAG N I R V F C R V R P L L P G E K Q A Q K Figure 1 The full-length kifc1 cDNA and corresponding amino acid sequence of Gekko japonicus. The Start codon ATG and termination codon TGA are marked with yellow highlighting.

The KIFC1 protein ofG. japonicuswas aligned with its homologues in various other species. The result showed the motor head represented a highly conserved region while the stalk and tail were more a characteristic of the species (Figure 3). From the alignment results, three kinds of conserved motor domains of the KIFC1 protein in C-terminal were predicted: three ATP binding sites (LAGSE, SSRSH and AYGQTGSGKT), a KIFC conserved domain (ELKGNIRVFCRVRP) and a microtubule binding site (YNEXXRDLL) (Figure 3). The phylogenetic tree indicated that the predicted KIFC1 ofG. japonicusrepresented a sister clade with that ofPlestiodon(Eumeces)chinensis and that this represented the highest homology to theG. japonicusKIFC1 protein among all of the selected species (Figure 4).

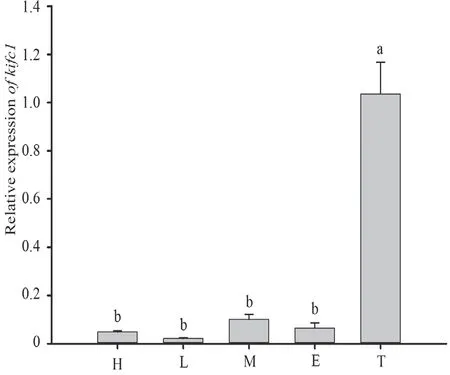

3.2.Kifc1mRNA expression in different tissuesKifc1mRNA expression in different tissues ofG. japonicuswas analyzed by real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR. A 256 bpkifc1cDNA fragment was amplified in the heart, liver, muscle, testis and epididymis. A 267 bp β-actin fragment amplified in all these tissues served as an internal control. From these results, the expression of

kifc1was highest in the testis (One-way ANOVA,P< 0.01) (Figure 5).

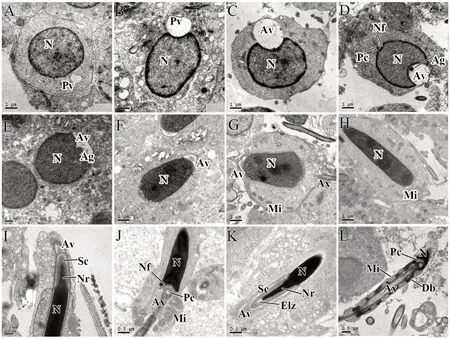

3.3. Ultrastructure ofG. japonicusspermiogenesisAccording to the terminology of Russellet al. (1990) for mammalian species, spermiogenesis of Schlegel’s Japanese gecko can be divided into seven steps. These incorporate the main processes of acrosomal formation, nuclear elongation, and chromosomal condensation. Round spermatids produced by the second meiotic division in the gecko testis represent the step 1 spermatids (Figure 6A), which marks the beginning of spermiogenesis. A large lightly stained vesicle, which originates from the budding vesicles hosted by the Golgi apparatus, and the centrally located spherical nuclei with a well-defined nuclear membrane, are the main characteristics of these spermatids. These spermatids often keep synchrony and share their cytoplasm and organelles via the direct connection of cytoplasmic bridges. Step 2 spermatids are well-defined by their large and towering acrosome that is in contact with the nuclear membrane. At this point the acrosomal granule within the acrosomal vesicle becomes visible (Figure 6B, C). From step 3 spermatids, we can see the acrosomal vesicle creating a deep indent in the apical nucleus which has now reached its final size. At this stage it is the round acrosomal granule resting on the inner acrosomal membrane that becomes the most apparent feature. On the other apex of the nucleus, an indentation called the nuclear fossa is formed, where the distal centriole locates in and elongates to form the flagellum. Later in the development, the acrosomal vesicle is gradually pushed out and begins flatten and widen and cover the nuclear surface (Figure 6D).

Figure 2 Prediction of KIFC1 secondary and tertiary structures of Gekko japonicus. (A) Three-domain structure of KIFC1: Head (311-672aa), Stalk (146-311aa) and Tail (1-146aa). (B) The tertiary structure of KIFC1. The globular head was made up of α-helix and β-sheet. The stalk mainly consisted of β-sheet. The tail showed a random shape.

Figure 4 A phylogenetic tree of KIFC1 homologues from various species through the neighbor-joining method. The GenBank accession numbers: Andrias davidianus (AEB71794), Anolis carolinensis (XP_008122574), Cynops orientalis (ADM53352), Danio rerio (NP_571281), Eriocheir sinensis (ADJ19048), Gallus gallus (NP_001075167), Homo sapiens (NP_002254), Macrobrachium rosenbergii (AFO63546), Mus musculus (NP_1182227), Plestiodon chinensis (AFP33411) and Xenopus laevis (NP_0011081003).

Figure 5 The Real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR analysis and statistical results of kifc1 mRNA expression in different tissues. Different letters (a and b) above the bars indicate significant differences between these tissues (One-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post hoc tests, P < 0.01). H: heart, L: liver, M: muscle, E: epididymis, T: testis.

The transitional step which marks the onset of elongation begins the step 4 stage of the spermatids (Figure 6E, F). Here the round step 3 spermatids begin their elongation and condensation phase. With the development of the spermatid nuclei, the cell membrane is extruded and results in the acrosomal vesicle and acrosomal granule widening further across the apex of each nucleus. This causes the nucleus to become flattened and a gradually flattening acrosomal vesicle to become apparent. During this process the dark acrosomal granule within the acrosomal vesicle also disappears.

Extreme condensation and elongation of the nucleus characterizes steps 5 to 7 spermatids where step 5 spermatids (Figure 6G) are longer and more elliptical compared to Step 4 spermatids. Mitochondria in the cytoplasm are aggregating to the tail at this time and we also observe the development of the flagellum (Figure 6G). Step 6 spermatids (Figure 6H) undergo further elongation and condensation causing them to become much thinner and longer. Late developing step 6 spermatids represent the termination of nuclear elongation upon its reaching of its maximum length. Step 7 (Figure 6I, J) spermatids undergo considerable nuclear condensation and cytoplasmic elimination. Here, a compartmentalized acrosome with acrosomal vesicle and subacrosomal cone (Sc) is distinguishable and covers on the apical surface of the nucleus. Step 7 nuclei stain more intensely than any of the previous elongating spermatids and are notably curved into a thin rod-like shape (Figure 6I). In this process some redundant cytoplasm is being eliminated and the sperm tail also completes its development. Once step 7 spermatids complete spermiogenesis, they are released as mature spermatozoa (Figure 6K, L). The mature spermatozoa are filiform and streamline in shape, with extremely long heads and tails. Here, the cytoplasm is eliminated until the distinguishable cell membrane boundaries can no longer be observed.

Figure 6 The process of spermiogenesis from step 1 spermatids to mature sperm in Gekko japonicus testis. (A) Step 1 spermatid; (B) and (C) Step 2 spermatid; (D) Step 3 spermatid; (E) and (F) Step 4 spermatid; (G) Step 5 spermatid; (H) Step 6 spermatid; (I) and (J) Step 7 spermatids; (K) and (L) Mature sperm. Ag: acrosomal granule; Av: acrosomal vesicle; Ax: axoneme; Db: dense body; Elz: epinuclear lucent zone; Mi: mitochondria; N: nucleus; Nf: nuclear fossa; Nr: nuclear rostrum; Pc: proximal centriole; Pv: proacrosomal vesicle; Sc: subacrosomal cone.

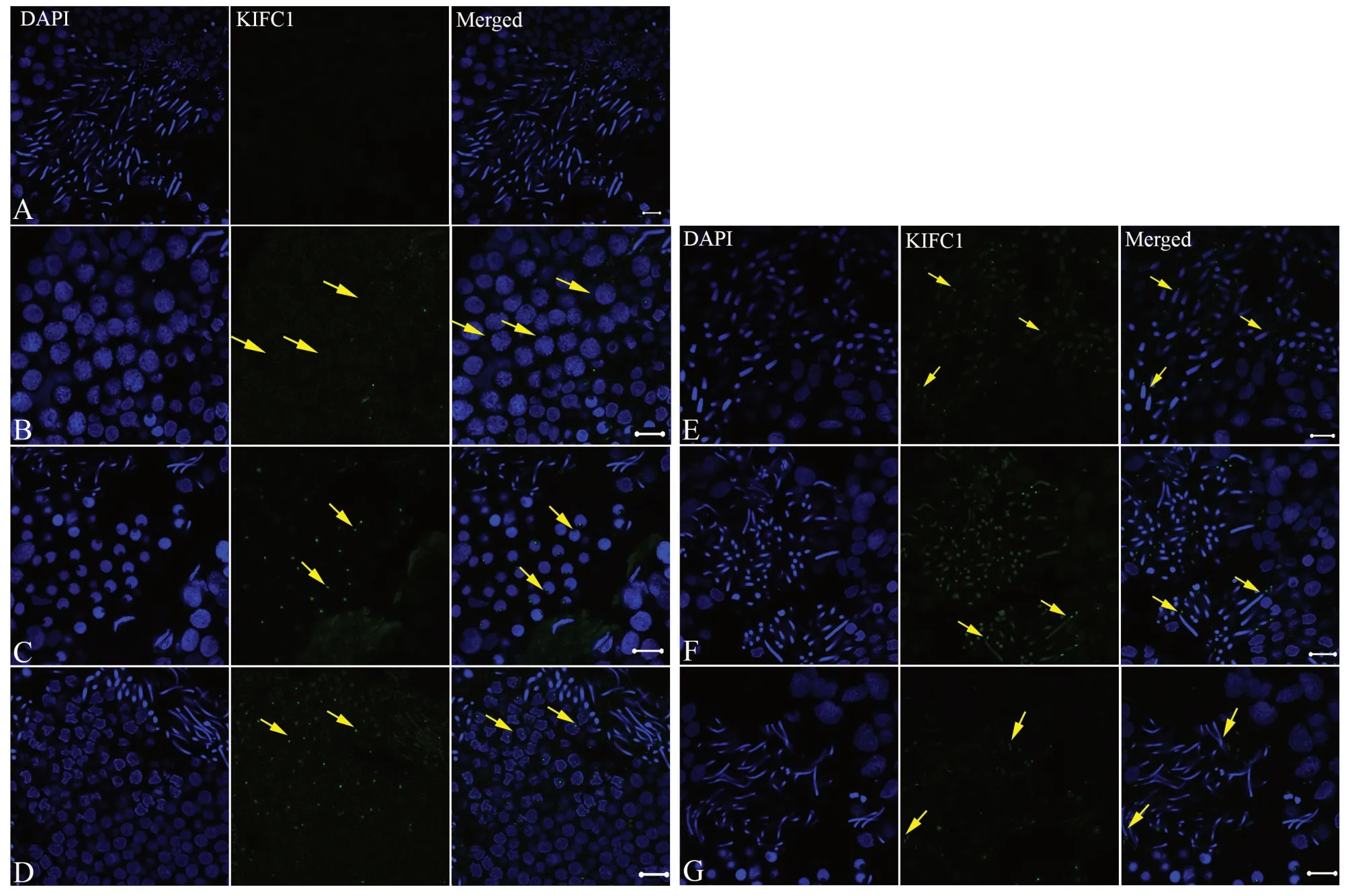

3.4. Temporal and spatial expression pattern ofkifc1mRNA duringG.japonicusspermiogenesisAfter the process of spermiogenesis, as elaborated through the results of spermiogenic ultrastructure, the temporal and spatial expression profile ofkifc1mRNA inG. japonicuswas detected using fluorescencein situhybridization. We found that the localization ofkifc1mRNA signal was visible during the process of spermiogenesis. In addition, these signal locations related to the formation of the acrosome and to the morphogenesis of the nucleus (Figure 7). Step 1 spermatids with round nuclei and homogeneous nucleoplasm represent the beginning of the progress of spermiogenesis. Throughout the round step 1 spermatids stage, almost no specifickifc1signal can be seen in cytoplasm or nucleus (Figure 7B). Subsequently, from the moment of acrosomal vesicle formation (step 2 spermatids) to that of the acrosomal vesicle insertion deep into the nucleus (step 3 spermatids),kifc1mRNA signals are mostly concentrated in the indentation of the apical nuclei (Figure 7C). Step 4 spermatids mark the transition period and appear irregular in shape and show a nuclear fossa at the terminal. At this stage, the signals are also concentrated on the indentation where the acrosome finally forms and the signal intensity at this stage is almost identical as that of step 2 and 3 spermatids (Figure 7D).

Figure 7 The spatio-temporal expression of kifc1 mRNA during spermiogenesis of Gekko japonicus. (A) No kifc1 signal was observed in the control group; (B) In step 1 spermatid, almost no kifc1 signal was detected; (C) In steps 2 and 3 spermatid, the signal was centralized at the top of the nucleus; (D) In step 4 spermatid, the kifc1 signal was centralized at the location of acrosomal formation and began to be detected in nucleus. (E) In step 5 spermatid, the signal was concentrated mainly in the acrosome and further increased in nucleus; (F) In steps 6 and 7 spermatids, the signal was concentrated mainly in the acrosome and nucleus; (G) In the mature sperm, the kifc1 mRNA signal only appeared in the acrosome. Scale bar was 10 μm.

The elongated spermatids are firstly seen at step 5 spermatid stage whose nuclei are becoming more elongated than those of step 4 spermatids and are beginning to appear coniform in shape. At this time, the signals ofkifc1mRNA are clearly distributed on the tips of the coniform nuclei (Figure 7E), with the signals within the nuclei also obviously increased. Step 5 spermatids continue their development and then proceed into step 6 and 7 spermatids. As compared with step 5 spermatids, step 6 and 7 spermatids undergo further condensation and elongation and begin to appear as thin rods in sagittal sections (Figure 7F). Eventually, both the length and condensation of the nuclear head reaches a maximum. In those spermatids, we can also detect thekifc1mRNA signals occurring in a similar localization pattern to that of step 5 spermatids, but with the signals increased to their highest levels, as revealed by fluorescencein situhybridization (Figure 7E). Late developing step 7 spermatids then undergo their cytoplasmic elimination and are released as filiform mature spermatozoa (Figure 7F). Thekifc1mRNA signals of the mature spermatozoa are then dramatically decreased (Figure 7G) where we only see weak signals occurring in the acrosome and almost no signal remaining in the filamentous nuclei (Figure 7G).

4. Discussion

4.1. Kinesin motors may be involved in spermiogenesis

The round spermatids within the reptilian testes experience perhaps the most dramatic change in nucleus and cytoskeleton as any cell type of the adult vertebrate body. This process takes approximately five to eight weeks in reptiles (Gribbins, 2011) whilst it may only take around four weeks in most mammals (Russellet al., 1990). During spermiogenesis, three major morphological courses take place: development of the acrosome, DNA condensation/nucleus elongation, and flagellum formation. After these, the mature spermatozoon, a highly hydrodynamic motile cell with an acrosome complex,nucleus, and flagellum, is eventually produced.

In the past few years, increased numbers of proteins of the kinesin superfamily have been identified to participate in, and even be crucial for the process of spermatogenesis in the male testis of both vertebrates and crustaceans. It has been reported that Kif18A, a member of the kinesin-8 family, plays an essential role in mitotic and meiotic chromosome alignment to protect chromosome congression in the testes of male mice (Liuet al., 2010). Another three kinesin proteins, the kinesin-9 proteins KRP3A and KRP3B and kinesin-1 protein KIF5C, were also suggested to have a role in acrosome biogenesis as well as in nuclear condensation (Mannowetzet al., 2010; Zouet al., 2002). KIF17b, KIF3A and KIF3B are three members of the kinesin-2 family. KIF17b and KIF3A were both seen to be situated in the manchette as supporters of nuclear elongation (Kotajaet al., 2004; Lehtiet al., 2013). KIF3A and KIF3B were also reported to have a considerably close relationship to sperm tail formation (Danget al., 2012; Lehtiet al., 2013). Our result, by method of fluorescencein situhybridization, indicatedkifc1mRNA signals were mainly distributed in the acrosome and the nucleus of the various developmental stage spermatids. Hence, we make a conjecture that KIFC1 participates in the process of spermiogenesis ofG. japonicusand may have a crucial role in the head morphogenesis, including acrosome biogenesis and nuclear elongation/condensation.

Many studies have demonstrated thatkifc1is widely occurring and expressed in the spleen, hepatopancreas, gills, ovary and the testes of both invertebrates and vertebrates (Lawrenceet al., 2004; Nathet al., 2007; Wanget al., 2010b, 2012). This is consistent with its suggested performance in the transport of macromolecules and vesicles (Zhanget al., 2014), polar spindle formation (Zhuet al., 2005), and cell migration (Leopoldet al., 1992). Thekifc1mRNA expression ofG. japonicuscould be examined via real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR in all the selected tissues, including the testis, heart, liver, muscle and epididymis. The expression ofkifc1in the testis was the highest, and showed significant differences with that of heart, liver, muscle and epididymis. The high level ofkifc1expression in the testis ofG. japonicussuggested a similar pattern with that of other examined species and implied special functions related to spermiogenesis in the testis ofG. japonicus.

4.2. KIFC1 may participate in acrosomal formation and nuclear shaping during spermiogenesis of G. japonicusThe expression and functions of C-terminal kinesin protein KIFC1 have been reported in many animals from aquatic invertebrates to mammalian. During spermiogenesis of crustaceans, such asEriocheir sinensis(Wang and Yang, 2010),Procambarus clarkia(Maet al., 2017a),Portunus trituberculatus(Maet al., 2017b), KIFC1 was mainly in the acrosome and around the reshaping nucleus, which closely related to the acrosome formation and nucleus reshaping. In cephalopods, such asOctopus tankahkeei(Wanget al., 2010b, 2010c) andSepiella maindroni(Tanet al., 2013), the parallel distribution of KIFC1 was found in acrosome and nucleus, but except in tail. KIFC1 signal was only detected in the long tail of late-stage spermatids ofO. tankahkeei. Therefore, inO. tankahkeei, KIFC1 was involved in not only acrosome formation and morphogenesis of sperm nucleus, but also in formation and maintenance of flagellum (Wanget al., 2010a). Interestingly, the dynamic of KIFC1 localization was almost the same inPhascolosoma esculenta(Phascolosomatidae, Sipuncula) (Gaoet al., 2019) andLarimichthys crocea(Sciaenidae, Chordata) (Zhanget al., 2017). KIFC1 signal transferred from the nucleus surrounding the tail/ midpiece, which suggests an important role of KIFC1 on nuclear shaping and midpiece formation in these two species. In the lizardP. chinensis, KIFC1 could be detected in the nucleus, acrosome and the flagellum of spermatids and it may be closely related to all the three events of spermiogenesis: acrosome biogenesis, nucleus reshaping and tail formation (Huet al., 2013). Finally, in mammals (e.g. rat), the localization of KIFC1 was associated with the Golgi, nuclear membrane, manchette, and the acrosomal vesicle, and KIFC1 was functional in the growing acrosome by Golgi transportation and in the sperm nuclear reshaping by manchette maintaining (Yang and Sperry, 2003). Therefore, from all these studies, the functions of KIFC1 in different species focused on acrosome biogenesis, nuclear morphogenesis and tail formation.

In the present study, to further explore the functions of the KIFC1 protein in spermiogenesis ofG. japonicus, we investigated the distribution ofkifc1mRNA in spermiogenic cells by conducting fluorescencein situhybridization. From the results of the spatial and temporal distribution pattern ofkifc1mRNA, some important messages, such as when and where this motor protein was expressed during spermiogenesis, were uncovered. At the beginning step of spermiogenesis, the motor protein KIFC1 was not expressed, which may indicate no function for step 1 spermatids. With the development of the acrosomal vesicle in the step 2 to 4 spermatids, the gene transcripts ofkifc1were detected and concentrated in the indentation of the nucleus where the acrosome was localized. This likely indicated that the motor protein KIFC1 was involved in the formation of the acrosome, which was consistent with previous reports inO. tankahkeei,P. chinensisandE. sinensis(Huet al., 2013; Wangetal., 2010b; Yuet al., 2009). With the nucleus elongation and condensation of the later steps, the signal could be observed in the acrosome, and became gradually stronger in the spermatid nucleus. This phenomenon indicated that KIFC1 may also participate in the elongation and condensation of the nucleus. When the spermatid achieved its final morphology and became a mature sperm, the mRNA signal became weaker and weaker and finally disappeared. Based on the expression pattern ofkifc1mRNA in spermiogenesis ofG. japonicus, we speculated that KIFC1 may be tightly associated with the formation of the acrosome and with nucleus morphogenesis.

In conclusion, we describe the expression of thekifc1gene in the testis of theG. japonicusfor the first time, and specifically detect thekifc1signal in the acrosome and the nucleus of spermatids. The study has great significance for the reconstruction of evolutionary route at the molecular level and it provides new clues for understanding functions of kinesin motors during spermatogenesis in the family Gekkonidae. However, the specific mechanism played by thekifc1gene still remains unclear. Further replications and other studies are required to clarify the current findings.

AcknowledgementsThis project was supported by the Natural Sciences Foundation of China (31170376), Zhejiang Province Natural Science Foundation of China (LY16C030001; LY18C040005). We thank Wanxi YANG for the assistance in the experiment.

杂志排行

Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- The Marking Technology in Motion Capture for the Complex Locomotor Behavior of Flexible Small Animals (Gekko gecko)

- Thermal-physiological Strategies Underlying the Sympatric Occurrence of Three Desert Lizard Species

- Altitudinal Variation in Digestive Tract Lengh in Feirana quadranus

- Mitochondrial Diversity and Phylogeographic Patterns of Gekko gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae) in Thailand

- A New Species of Megophryid Frog of the Genus Scutiger from Kangchenjunga Conservation Area, Eastern Nepal