Choledochal cysts: Similarities and differences between Asian and Western countries

2019-07-24GeorgeBaisonMorganBondsWilliamHeltonRichardKozarek

George N Baison, Morgan M Bonds, William S Helton, Richard A Kozarek

Abstract Choledochal cysts (CCs) are rare bile duct dilatations, intra-and/or extrahepatic,and have higher prevalence in the Asian population compared to Western populations. Most of the current literature on CC disease originates from Asia where these entities are most prevalent. They are thought to arise from an anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction, which are congenital anomalies between pancreatic and bile ducts. Some similarities in presentation between Eastern and Western patients exist such as female predominance, however, contemporary studies suggest that Asian patients may be more symptomatic on presentation.Even though CC disease presents with an increased malignant risk reported to be more than 10% after the second decade of life in Asian patients, this risk may be overstated in Western populations. Despite this difference in cancer risk,management guidelines for all patients with CC are based predominantly on observations reported from Asia where it is recommended that all CCs should be excised out of concern for the presence or development of biliary tract cancer.

Key words: Choledochal cyst; Cholangiocarcinoma; Asian populations; Western populations; Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction

INTRODUCTION

Choledochal cysts (CCs), congenital dilatations of the biliary tree that may be either extrahepatic and/or intrahepatic, are uncommon with an incidence that ranges from 1 in 100000-150000 live births in Western populations, to 1 in 1000 in some Asian populations[1-7]. Most of what is known about CCs comes from Asia[2,6,8-10], although there have been a few large Western cohorts reported[2,6,11-13]. Some clinicians postulate that CC disease in the West is different from CC disease in the East and different management strategies should be employed. Therefore, we present an overview of CC disease in the West and East noting the similarities and differences in presentation, diagnosis, and management.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

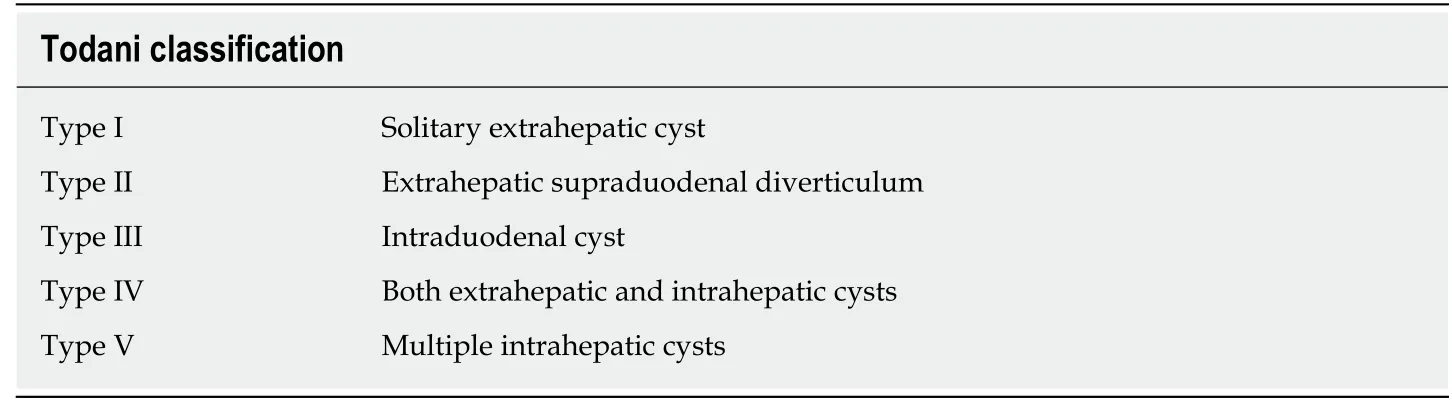

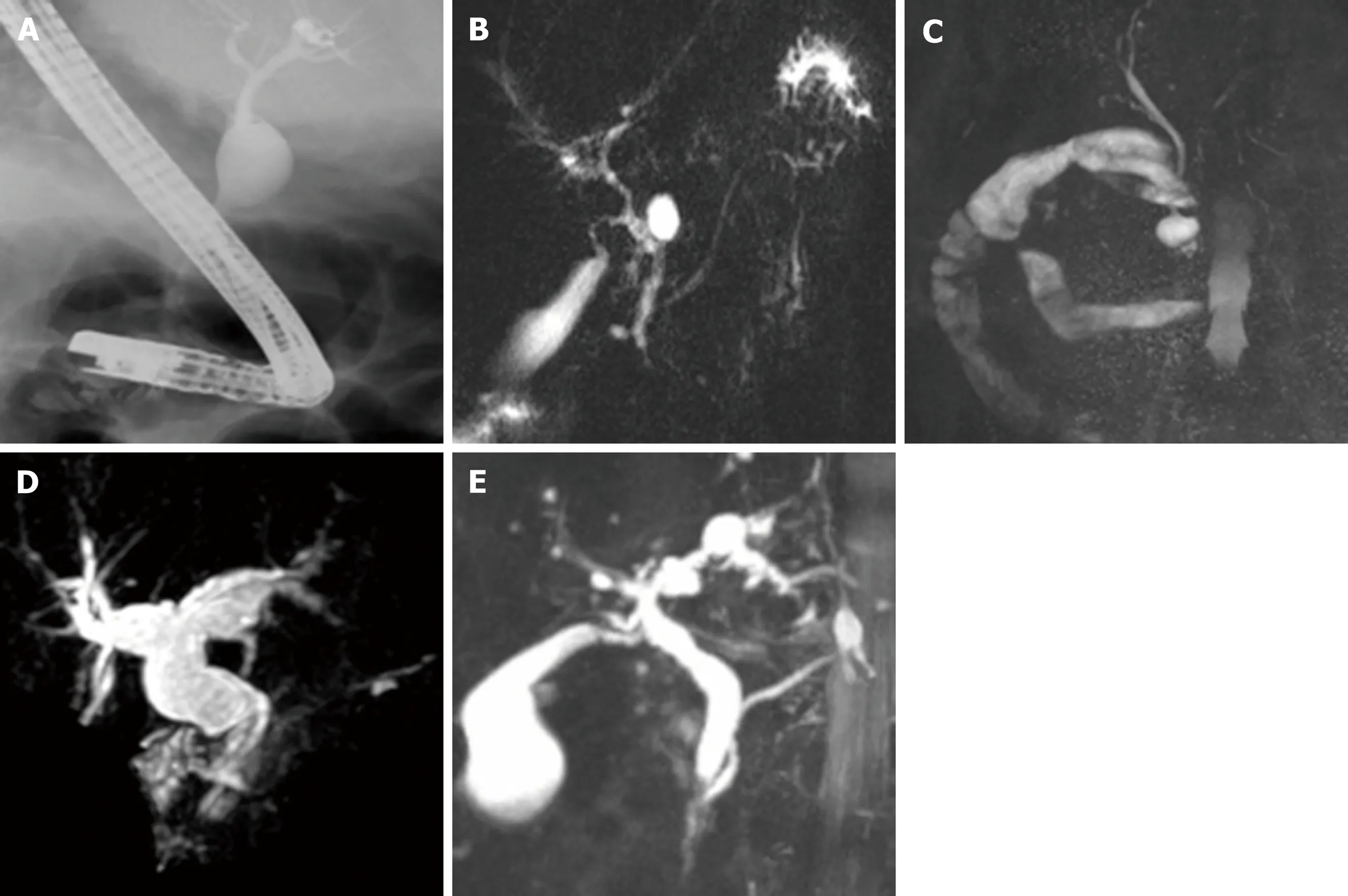

CCs are typically classified according to the Todani classification, modified from the Alonso-Lej classification[14-16]. This classification outlines five types of CCs: Type I, the most common, described as a solitary extrahepatic cyst; type II is an extrahepatic supraduodenal diverticulum; type III CC is an intraduodenal cyst, which is sometimes referred to as a choledochocele; type IV is comprised of both extrahepatic and intrahepatic cysts; and type V, comprised of multiple intrahepatic cysts, and often referred to as Caroli's disease[5,16](Figure 1A-E and Table 1). In both Eastern and Western populations, type I CCs have been noted to be most common, ranging from 65%-84% in Eastern cohorts and 67%-73% in Western cohorts. Type IV CCs are the next most common with 6%-30% in the East compared to 18%-19% in Western cohorts(Table 2).

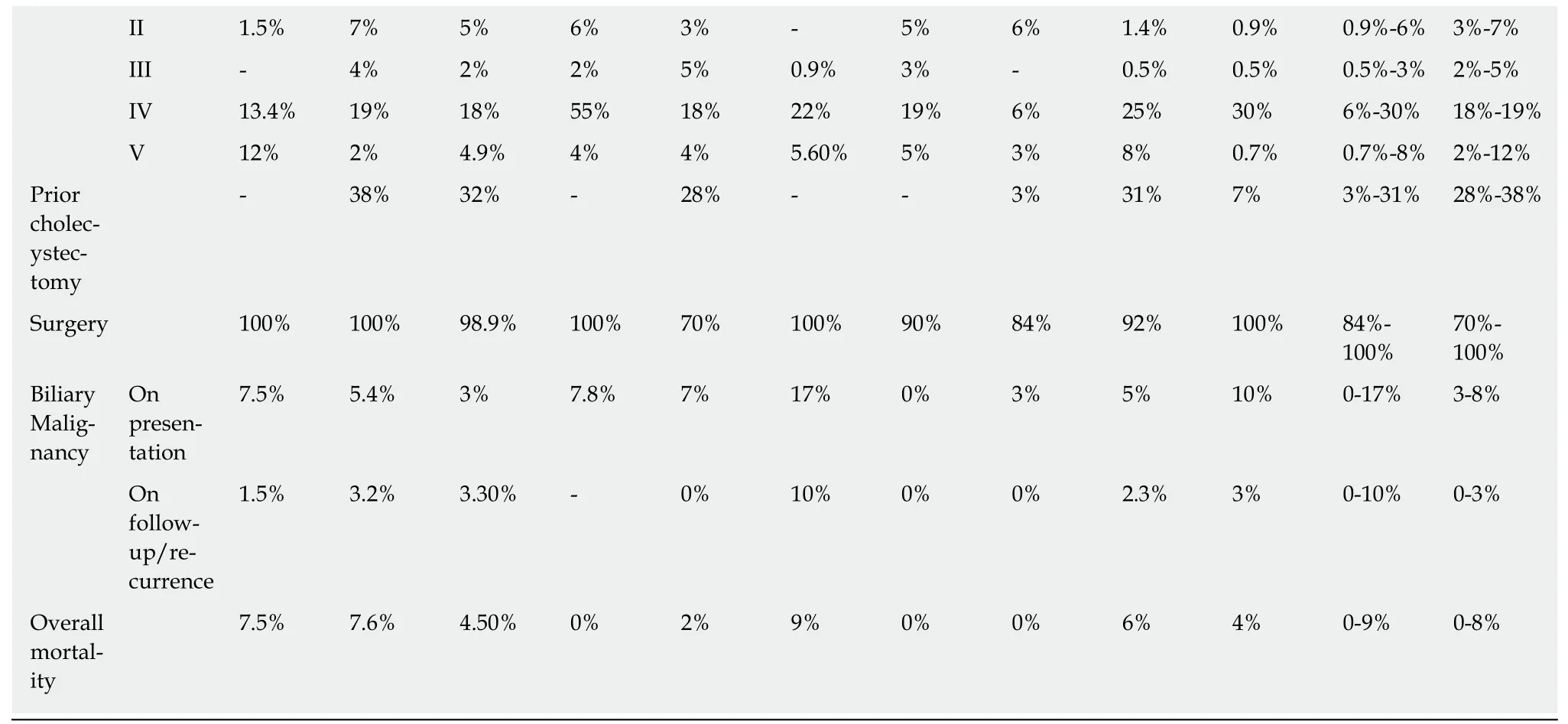

The similar distribution in CC types between Eastern and Western cohorts is likely related to the similar etiology of CCs. Babbitt's theory is the most commonly proposed theory and states that CCs result from an anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction(APBJ) where the pancreatic duct and the bile duct connect 1-2 cm proximal to the sphincter of Oddi[3,4,17-22]. The clinical entity of APBJ has become widely accepted to be etiologic in the pathogenesis of biliary carcinogenesis in patients with CC[8,11,23-25].There are several proposed classifications for APBJ, but one common classification is the simplified Komi's classification, so-called Association Française de Chirurgie classification that includes three subtypes: Type I (C-P type), type II (P-C type), and type III (complex type) with ‘‘anse-de-seau'' (Figure 2A-C)[22].

The long common channel associated with APBJ facilitates reflux of pancreatic juice into the biliary tree, causing increased pressure and possible proteolysis within the CBD culminating in ductal dilation[4,26]. High amylase levels have been noted in CC bile, adding evidence to this theory[27]. This reflux of pancreatic juices also leads to biliary tree inflammation, epithelial breakdown, mucosal dysplasia, and, potentially,malignancy[21,27]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the inflammation and bile duct breakdown are exacerbated by high trypsinogen and phospholipase A2 levels in bile of patients with CCs[28]. However, some authors have questioned this theory because an APBJ is found in only 50%-80% cases of CCs, there is no pancreatic juice reflux in antenatally detected CCs, and neonatal acini do not secrete sufficient pancreatic enzymes[29]. Animal studies suggest that obstruction of the distal CBD may contribute to the development of CCs, particularly sphincter of Oddi dysfunction,which also causes pancreatic juice reflux into the biliary system[30]. Kusunoki et al[31]proposed a pure congenital theory in which fewer ganglion cells are seen in distal CBD in patients with CCs resulting in proximal dilation in the same manner as achalasia of the esophagus or Hirschsprung's disease[1,31].

Table 1 Classification of choledochal cysts according to the Todani classification

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

The demographics and clinical presentation of CC are similar between Eastern and Western populations, especially the female to male preponderance, ranging from 4:1 to 3:1[1,2,6]. Most CCs are diagnosed in children, although about 25% are discovered in adults[1]. In adults, the presentation is usually nonspecific and vague, with nonspecific abdominal pain being the most common symptom[1], but when the symptoms are more specific, they are typically acute biliary tract and/or pancreatic in nature[2].While some patients present with the classic triad of symptoms, abdominal pain,palpable abdominal mass, and jaundice, it is observed in only 25% of adults, although 85% of children have at least two features of this classic triad[4,6,32]. Furthermore, recent literature suggests increased rates of CC disease in adults[2,7]. While the trend in common presentation symptoms may be similar between the East and West, the literature suggests that associated biliary conditions such as cholecystitis, cholangitis,and choledocholithiasis may be more prevalent in Eastern patients on presentation[24,25](Table 2). Indeed, further investigation is necessary to delineate if this is a true difference between the two populations.

CC disease can be diagnosed using imaging modalities such as ultrasound,computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP),endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and endoscopic ultrasonography, with MRCP and ERCP considered the diagnostic methods of choice[6]. MRCP has been reported to have a 90%-100% sensitivity for detecting CCs[33].However, MRCP has a much lower sensitivity for delineating the pancreatic duct and common pancreaticobiliary channel of only 46%, which is lower when compared with CT cholangiopancreatography which has a reported sensitivity of 64%[33]. With recent advances in cross-sectional imaging, more asymptomatic cases are being discovered incidentally[2,6]. Though current practice on imaging and diagnosis is similar across continents, Asian patients are marginally more symptomatic on presentation; 88%-91% of Asian patients present with symptoms compared to 72%-85% of Western patients. Various reasons may account for this including potential difference in the use of imaging modalities in clinical practice between the East and West, such as difference in CC disease presentation or selection bias in various studies.

MALIGNANT RISK

CC disease is associated with various complications including obstructive jaundice,symptomatic choledocholithiasis, pancreatitis, cholangitis, spontaneous cyst rupture,secondary biliary cirrhosis, and cholangiocarcinoma[1]. Of particular concern is the increased risk of malignancy[6,18,34,35], which varies from 2.5% to 17.5%, with some reports as high as 21%[13,36-39]. Malignant risk in Western cohorts is likely overstated;the risk of malignancy may be higher in Eastern cohorts compared to Western cohorts, particularly in adults (Table 2). This high malignant risk in Asian cohorts has been the main driver for the current approach to CC disease management.

The risk of malignancy increases with age, reported to be lowest in the first decade of life at 0.7% and exceeding 10% after the second decade of life, suggesting that early diagnosis and treatment lead to a more favorable outcome[1,36,40]. Some studies have noted malignancy in up to 50% of patients with CC over the age of 60 years[24,25]. Not only is malignancy associated with age, but CC type. Todani et al[16]observed that of the patients who develop biliary malignancy, 68% occurred in type I, 5% in type II,1.6% in type III, 21% in type IV, and 6% in type V CCs[16]. Additionally, the malignant risk due to the presence of an APBJ has been well established in both Western and Eastern patients. At our institution, we have observed a 4-fold increase in malignancy in patients with CC and an APBJ when compared to those with CC without an APBJ[41]. Imazu et al[29]showed that regurgitation and stasis of pancreatic fluid into the biliary system not only cause inflammation, but lead to carcinogenesis. Histologic findings by Katabi et al[42]further corroborate Imazu et al's[29]findings that biliary cancer due to CC disease is a progression from inflammation, to dysplasia,metaplasia, and finally malignancy.

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography demonstrating choledochal cyst types. A:Type I choledochal cyst (CC) on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; B: Type II CC on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP); C:Type III CC on MRCP; D: Type IV CC on MRCP; E: Type V CC on MRCP. CC: Choledochal cyst; MRCP: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

A small subset of patients, from 0.7%-3%, develop cholangiocarcinoma after surgical resection, notably in patients with type I and IV cysts[11,15,24,41]. This indicates that the risk of malignancy does not return to baseline after CC resection in this group of patients[11,42]. The etiology behind these delayed malignancies remains unclear.Incomplete resection of the cyst or a field defect within the biliary epithelium leading to an increased inherent susceptibility have been suggested as possible etiologies for this persistent cancer risk[36,40]. Liu et al[40]observed a 33.3% risk of malignancy in patients with incomplete cyst resection compared with 6% after complete cyst resection. Many studies, both Western and Eastern, do not have follow-up intervals long enough to detect this persistent risk since it can take more than 3 decades to manifest. Some have therefore suggested careful postoperative lifelong follow-up,especially in cases where there is a high suspicion for incomplete resection[24,43,44]. The utility of life-long follow-up in Western patients where recurrence rates are reportedly as low as 0-3% has yet to be determined.

Malignancy in CC disease takes the form of both gallbladder and bile duct cancers.Lee et al[24]reported biliary tract malignancies in 9.9% of CCs, of which 50% were cholangiocarcinoma and 44% gallbladder carcinoma. A large-scale survey of 2561 patients with CC in Japan showed that in those patients who had cancer, 62.3% had gallbladder cancer, 32.1% had bile duct cancer, and 4.7% had both, which is similar to other reports[1,34]. Of note, gallbladder carcinoma is found in 5% of CC disease patients with APBJ[45], usually in patients in their sixth or seventh decade of life, when adult cohorts are investigated[4]. Thus, it is perceived that the likelihood of the development of both bile duct cancer and gallbladder cancer increases in patients with CC and APBJ, whereas there is a significant predilection for gallbladder cancer in APBJ patients without CC[18,20,46-48].

MANAGEMENT

The demographics of the population being treated must be taken into consideration when managing CC disease. While Western populations present a mix of racialdiversity, Eastern cohorts are almost exclusive of Asian descent. The effect of race on the natural history of CC has not been fully explored. Our institution's experience with CC disease suggests that presentation and malignant risk may be different between Asian and Caucasian patients, with malignant risk being higher in Asian patients[41]. Therefore, it is essential to further understand the risks posed by CC disease in Western patients in order to design appropriate management guidelines as it may represent a separate entity in the West compared to Eastern patients.

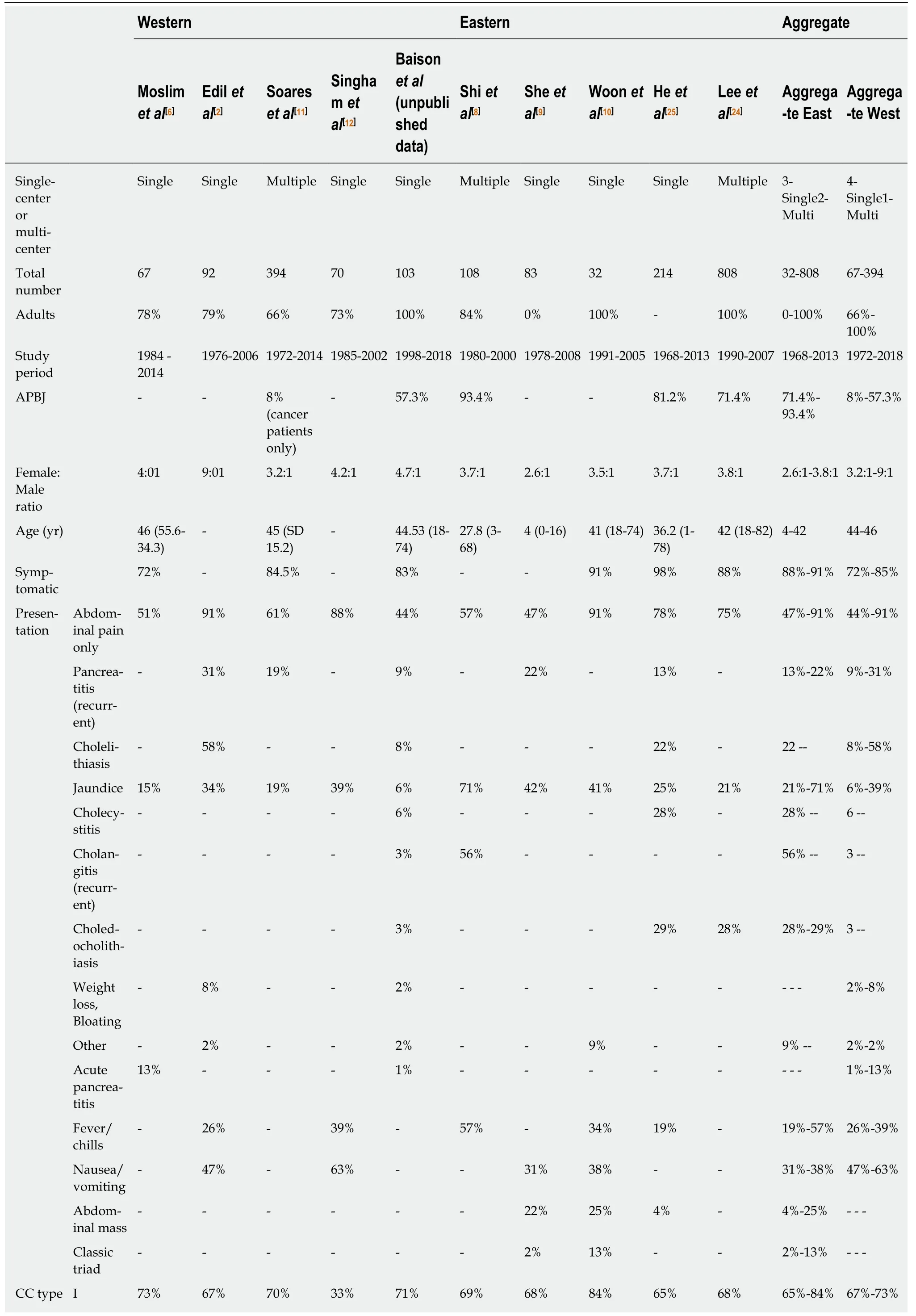

Table 2 Summary data for the five largest Western studies compared to the five largest Eastern studies, specifically investigating the presentation and management of choledochal cyst disease in the last 20 years

SD: Standard deviation; CC: Choledochal cyst; APBJ: Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction.

Currently, practice guidelines are based almost exclusively on data derived from the Asian literature. At present, there is no conclusive evidence to suggest that there is over-treatment of Western patients by using Asian guidelines, but the lower malignant risk in these patients necessitates further investigation into Western treatment outcomes. Current evidence suggests similar efficacy in treatment options between the East and West, however, this remains an area of limited data. This continues to evolve, especially as minimally invasive techniques are now being adopted for CC disease management[49-52]. More multi-institutional studies such as the one by Soares et al[11]and ideally international registries are needed to further understand CC disease in the West and devise management protocols.

The current standard of care for most CCs is complete excision of the cyst,specifically, resection from the bifurcation of lobar[4,6]hepatic ducts into the parenchyma of the pancreas near the junction of the pancreatic duct[1,3,20], coupled with cholecystectomy. Biliary tract continuity can be restored either by means of Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (HJ), hepaticoduodenostomy (HD), or jejunal interposition HD[6].However, this approach does not take into consideration various types of CC.Management should be tailored to the type of CC and the presence or absence of APBJ. Furthermore, advocating for resection in all patients may potentially be overly aggressive therapy, especially in Western patients where the risk of malignancy appears to be potentially overstated.

Surgical resection has been espoused to be the ideal strategy for type I CCs. There may, however, be a subset of patients in Western cohorts who are at low risk for developing cancer, in whom long term surveillance as opposed to surgical resection be considered. This includes patients who are asymptomatic, have undergone previous cholecystectomy, are older with medical comorbidity, and have no APBJ since their risk of malignancy appears to be quite low. However, there are no reports of patients managed by long term observation. Hence, long term risk of cancer and other biliary complications in such patients is currently unknown. Until such data become available, excision of all type I CC should be recommended to all Western as well as Eastern patients who can tolerate a major operation and are willing to do so.

Type II CCs are very rare and can be managed by simple excision. Usually these cysts are ligated at the neck and excised without the need for bile duct reconstruction[17]. However, occasionally extrahepatic bile duct excision is necessary.This is sometimes encountered in patients where associated inflammation causes intimate adhesion of the diverticulum to the extra- or intrahepatic biliary tree,depending on disease location, leading to technical challenges in liberating the diverticulum from the bile duct[5].

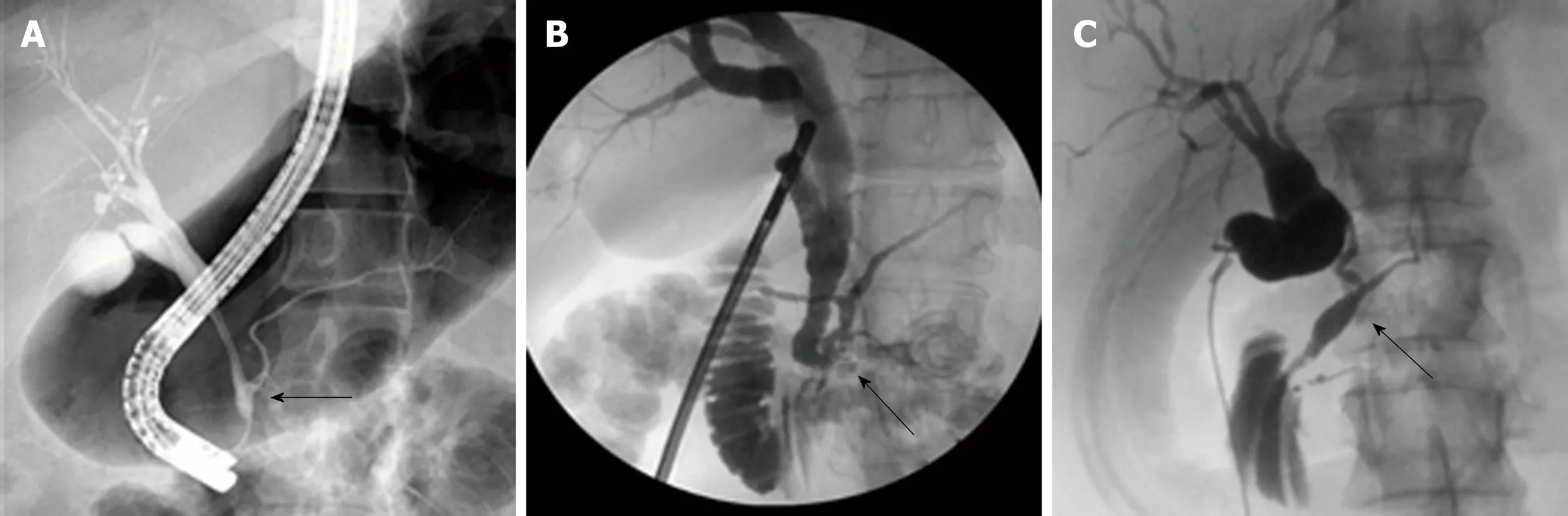

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and/or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showing anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction types. A: P-C anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction (APBJ) from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; B: Complex APBJ from intraoperative cholangiogram (IOC); C: C-P APBJ from IOC. Arrows point to junction with common channel. IOC: Intraoperative cholangiogram; APBJ: Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction.

Type III CCs, sometimes referred to as choledochoceles, are discrete from other CC diseases and their origin has been long debated[6,53]. One hypothesis is that these cysts may originate from a rudimentary inferior embryonic bud of the ampulla of Vater, or an acquired anomaly as a result of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction or obstruction[53];thus, choledochoceles may not represent a true form of CC. Most patients with type III CCs present to interventional gastroenterologists rather than surgeons. Type III CCs were historically treated via transduodenal excision and sphincteroplasty.Currently endoscopic sphincterotomy with cyst de-roofing is regarded as the treatment of choice for type III cysts[54,55]. Regardless, these patients should undergo periodic endoscopic surveillance since malignancy has occasionally been reported in choledochoceles[17].

Management, especially the operative approach, in type IV CC remains controversial. Visser et al[13]suggested excising the extrahepatic component of the cyst alone with concomitant HJ. However, hepatic resection in patients with unilobar disease[1]and liver transplantation in patients with bilobar disease should be considered, especially in patients with extensive intrahepatic dilation associated with complications, such as stones, cholangitis, or biliary cirrhosis[13,56,57]. We have found that for most patients, extrahepatic resection has been sufficient, although we concur that hepatic resection and transplantation should remain as tools in the surgeon's armamentarium when dealing with type IV CCs.

The management of type V CCs (Caroli's disease) is complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes endoscopy, interventional radiology, and surgery.Surgical treatment options include segmental or lobar hepatic resection and liver transplantation depending on the extent of the disease and presence of impaired hepatic function[6]. When the intrahepatic CC disease is localized without congenital hepatic fibrosis, segmental hepatectomy should be considered[58]. Percutaneous or endoscopic drainage and stents are used for palliative therapy. For diffuse disease with life-threatening complications, liver transplantation is the most viable option[1].

CONCLUSION

CC disease has a distinct presentation in the Eastern population yet shares some commonality with Western patients. However, some reported differences in presentation, malignancy risk, and patient demographics between Western and Eastern populations should spur further investigation into CC disease in Western patients to understand this disease and tailor management guidelines to Western populations. For now, the management of CC disease continues to be driven by the Asian literature. Large multi-institutional studies in the West with decades of followup are necessary to better understand the natural history of CC disease , and in particular the risk of biliary tract cancer, in Western patients.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Diuretic window hypothesis in cirrhosis: Changing the point of view

- Fluoroquinolones for the treatment of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in liver transplantation

- Reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with hemolymphoproliferative diseases, and its prevention

- Current status of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with surgically altered anatomy

- Gastro-duodenal disease in Africa: Literature review and clinical data from Accra, Ghana

- Screening of aptamers and their potential application in targeted diagnosis and therapy of liver cancer