Reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with hemolymphoproliferative diseases, and its prevention

2019-07-24CaterinaSagnelliMariantoniettaPisaturoFedericaCalSalvatoreMartiniEvangelistaSagnelliNicolaCoppola

Caterina Sagnelli, Mariantonietta Pisaturo, Federica Calò, Salvatore Martini, Evangelista Sagnelli,Nicola Coppola

Abstract Reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication is characterized by increased HBV-DNA serum values of about 1 log or by HBV DNA turning positive if previously undetectable in serum, possibly associated with liver damage and seldom life-threatening. Due to HBV reactivation, hepatitis B surface antigen(HBsAg)-negative/anti-HBc-positive subjects may revert to HBsAg-positive. In patients with hemo-lymphoproliferative disease, the frequency of HBV reactivation depends on the type of lymphoproliferative disorder, the individual's HBV serological status and the potency and duration of immunosuppression. In particular, it occurs in 10%-50% of the HBsAg-positive and in 2%-25% of the HBsAg- negative/anti-HBc-positive, the highest incidences being registered in patients receiving rituximab-based therapy. HBV reactivation can be prevented by accurate screening of patients at risk and by a pharmacological prophylaxis with anti-HBV nucleo(t)sides starting 2-3 wk before the beginning of immunosuppressive treatment and covering the entire period of administration of immunosuppressive drugs and a long subsequent period, the duration of which depends substantially on the degree of immunodepression achieved. Patients with significant HBV replication before immunosuppressive therapy should receive anti-HBV nucleo(t)sides as a long-term (may be life-long)treatment. This review article is mainly directed to doctors engaged every day in the treatment of patients with onco-lymphoproliferative diseases, so that they can broaden their knowledge on HBV infection and on its reactivation induced by the drugs with high immunosuppressive potential that they use in the care of their patients.

Key words: Hepatitis B virus reactivation; Hepatitis B virus infection; Hemolymphoproliferative diseases; Immunosuppressive therapy; Hepatitis B virus therapy;

INTRODUCTION

Although universal hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination has been successfully applied worldwide and effective drugs for a long-term suppression of HBV have been extensively applied, chronic HBV infection remains a serious health problem in most countries because of the large number of subjects with chronic HBV infection living in most of the nations. Two billion people worldwide had contact with HBV (overt or occult HBV infection), and nearly 240 million people had chronically HBV infected[1].While for individuals with overt HBV infection [hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive] there are well-standardized clinical and therapeutic strategies. In occult HBV infection patients (HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc negative and HBV-DNA positive) these strategies are not so well defined[2-10].

HBV reactivation, a phenomenon characterized by increased HBV-DNA serum values of about 1 log or by HBV DNA turning positive if previously undetectable in serum, mostly occurs in a context of temporary or permanent immunosuppression.HBV reactivation in patients with occult HBV infection may also determine a reappearance of HBsAg in serum, possibly associated with an acute hepatic exacerbation characterized by an elevation in liver enzymes above the normal values and seldom by increased bilirubin levels[11].

Clinical conditions leading to HBV reactivation are human immunodeficiency virus infection and the immunosuppression induced by drugs used for autoimmune diseases, neoplastic diseases and organ transplants[12]. Noteworthy, HBV reactivation most frequently develops in patients with serious hematologic disorders characterized by a worse prognosis[13]. The reported percentage of subjects with HBV reactivation ranges between 2% in Europe to over 10% in eastern Asia, estimates,however, are approximate, depending on the frequency of the different clinical situations in which the phenomenon occurs[14].

HBV INFECTION: PIVOTAL CONCEPTS

HBV infection is responsible for a variety of clinical forms. It begins as acute hepatitis that evolves in healing in most cases, but in a minority of cases it progresses to chronic forms, such as an inactive carrier state, chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis, the last one potentially leading to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[15]. HBV is a DNA virus enveloped double-stranded virus belonging to the hepadnaviridae family that infects hepatocytes, and its DNA may be detected also in mononuclear cells[16]. HBV has no direct cytotoxic activity, but it induces hepatocyte necrosis through an immunepathogenetic mechanism that includes the cytolytic action of cytotoxic T cells presensitized to viral antigens[17,18].

Ten HBV genotypes (A-J) have so far been identified, some of which further subclassified in sub-genotypes. These genotypes have epidemiological value since differently distributed worldwide[19-43], but their clinical impact has not been fully elucidated.

In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated 257 million people, are living with chronic HBV infection worldwide. HBV endemicity is usually represented by the prevalence of HBsAg chronic carriers in the general population in a defined geographical area. Three levels of endemicity have been defined: (1) High endemicity with an HBsAg prevalence over 8%, observed in some countries in sub-Saharan Africa and eastern Asia; (2) Intermediate endemicity with HBsAg levels between 2%-8%observed in most Mediterranean countries, in several countries in the Middle East and in some countries in South America; (3) Low endemicity with an HBsAg prevalence lower than 2% observed in the United States of America, Canada and western Europe[31,24].

In geographical areas with high endemicity, HBV infection is prevalently spread from mother to child at birth and between siblings in early childhood[44,45], whereas in areas at low endemicity, unsafe sexual habits and sharing of contaminated needles,especially among injection drug users, are the major routes of transmission[46].Universal HBV vaccination of new born babies have resulted in a dramatic,progressive reduction in HBV transmission in all countries where this prophylactic procedure has been applied[28].

The outcome of HBV infection is age-dependent. Once acquired, HBV infection causes symptomatic acute hepatitis in approximately 1% of perinatal infections, in 10% of infections in early childhood (1-5 years), in 30% of children aged more than 5 years and in most infected adults. Fulminant hepatitis develops in 0.1%-0.6% of acute hepatitis cases and is more frequent in young adults; mortality from fulminant hepatitis B is approximately 70%. HBV infection progresses to chronicity with a frequency inversely related to the age at HBV acquisition, approximately 80%-90% in babies infected perinatally, in about 30% in children aged less than 6 and in less than 5% in adults[47].

Patients recovering from acute hepatitis B become HBsAg negative but a covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) persists in the hepatocytes and anti-HBc in serum;many of them become anti-HBs positive and are protected from eventual HBV reinfection. For most patients with chronic HBV infection, the clinical presentation progressively varies from a chronic HBsAg carrier state with no evidence of liver disease, to chronic hepatitis (first HBeAg-positive and then HBeAg-negative), and finally to liver cirrhosis (compensated in a first phase and therefore decompensated),with or without HCC[48,49]. Recently, the guidelines of the European Association of Study of the Liver have simplified this classification by identifying 4 phases: (1)HBeAg-positive infection (the old “immune-tolerant phase”); (2) HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis (the old “immune-reactive phase”); (3) HBeAg-negative infection(the old “immune-control phase”); (4) HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis (the old“immune-escape phase”)[50]. A virological condition called “resolved HBV infection”has also been identified, characterized by a low HBV-DNA level in liver tissue and possibly in serum in HBsAg-negative subjects, conceptually overlapping the definition of occult HBV infection[51-56]. For epidemiological studies and in clinical practice, the presence of anti-HBc in serum has been used by several researchers as a surrogate marker of hepatocytic integrated HBV DNA and cccDNA, given the objective difficulty of obtaining a liver biopsy in HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive subjects in good clinical conditions

HBV is considered an oncogenic virus, but its carcinogenic action is the result of its interaction with the presence of cirrhosis and with the host immune system[7,9,10,57-64]. In the absence of specific treatments, HBsAg positive cirrhotic patients develop HCC at a rate of about 2% per year in western countries and 3% in eastern countries[49].Antiviral therapy has dramatically changed the outcome of HBV patients[62]since it may prevent the progression of chronic hepatitis B to the advanced stages of liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and, in nearly half of cirrhotic patients to HCC[50].

Interferons (IFNs) and nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) are used to treat chronic HBV infection. Among IFNs, pegylated IFN has a more convenient dosing schedule and improved efficacy, but the nucleo(t)side analogues entecavir (ETV), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) are commonly preferred because less frequently induce severe adverse reactions, have a high barrier to antiviral resistance and almost always provide a steady suppression of viral replication[50]. At present, the treatment endpoint is the reduction of the disease to an inactive stage, with HBeAg loss if previously detectable, HBV DNA undetectable or at a low level in serum and normal liver enzymes, a clinical condition associated with a remarkable improvement even in cirrhotic patients that may prevent the development of HCC in nearly half of the cases[27,63]. However, both IFN and nucleo(t)side treatments do not eradicate HBV infection because HBV DNA persists in hepatocytes in an integrated form and as cccDNA and a reactivation of viral replication may occur once treatment has been discontinued. Future treatments, already under study,consider the combined use of antivirals directed against new targets and possibly immunomodulatory drugs[65].

VIROLOGIC AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF OCCULT HBV INFECTION

Patients with occult HBV infection showed HBsAg negativity and anti-HBc positive,at times associated with the antibody to surface antigen (anti-HBs), HBV DNA undetectable or detectable at very low levels in serum and normal liver enzymes;HBV DNA, however, persists within the hepatocytes as cccDNA and integrated DNA[66], whose active replication is inhibited by innate and adaptive immune responses (HBV-specific T-cell and neutralizing antibodies). Such inhibition is unable to eradicate all forms of HBV DNA and an HBV reservoir persists in the liver tissue.

A reduction in the immune-mediated control of HBV replication in these reservoirs,due to any cause, may favor the reactivation of HBV replication[67,68], which may induce an acute exacerbation of chronic HBV infection both in patients with HBsAg positivity (≥ 2 log10 rise in the HBV-DNA level) and in those with occult HBV infection who, in this case may revert to HBsAg-positive. This acute exacerbation is characterized by an increase in liver damage highlighted by an increase in ALT or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) ≥ 3-times the baseline serum values, which in its severe forms is accompanied by jaundice and may progress to severe hepatic failure if effective treatment is delayed. This event may lead to rapid life-threatening liver decompensation requiring urgent liver transplantation to prevent a fatal outcome.This critical clinical condition could simply be prevented by adopting a therapeutic prophylaxis with an effective nucleo(t)side against HBV, in which case the use of effective immunosuppressive drugs for neoplastic or hematological diseases is foreseen.

If HBV reactivation for some reason is not prevented, effective antiviral therapy should immediately be administered to reduce, if still in time, the entity of the associated clinical events through a pharmacologic control of HBV replication; this can lead, in cases with a favorable prognosis, to a gradual reduction in the levels of serum HBV-DNA, a progressive return of liver enzymes to the baseline values and a gradual recovery of the liver lesions[11]. Accordingly, HBV reactivation may occur years after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) due to low immune reconstitution[69]. Therefore, pharmacological prevention of HBV-reactivation prophylaxis must start within the recommended times, can be very long-lasting and require an accurate long-term surveillance.

RISK FACTORS

The risk factors of HBV reactivation concern either the patients, HBV, the underlying disease or the immunosuppressive regimen.

Patient

Male sex and more than 50 years old are risk factor for HBV reactivation. Yeo et al[70]in 600 cancer positive HBsAg patients who underwent chemotherapy, found an incidence almost 3-times higher in men than in women. It has also been observed that older patients are more likely to have HBsAg positivity, persistent levels of HBVDNA in serum and cccDNA in the liver, a virological condition increasing the risk of HBV reactivation[71].

Virus

As mentioned above, factors associated with HBV reactivation include HBsAg positivity, HBeAg positivity and high levels of HBV DNA before the onset of pharmacological immuno-suppression[72]. In contrast, the presence of anti-HBs antibodies has been shown to protect against reactivation, although the antibody titer necessary to achieve this effect is unknown[73].

Underlying diseases

As regards the magnitude of risk factors for HBV reactivation associated with the underlying disease, the data are not so clear because it is difficult to distinguish the contribution of the individual disease from that of the treatment used. In a recent study of 1962 patients with hematological malignancies in Taiwan, the authors noted similar incidences of HBV reactivation among patients with various types of hematological cancer[74].

Lymphoma is the most common underlying disease favoring HBV reactivation[75],possibly because HBsAg-negative patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL)frequently present a direct HBV infection of lymphocytes, chronic antigenic stimulation and associated B-cell proliferation. Onco-hematological patients undergoing immunosuppression with aggressive chemotherapy or HBV reactivation[51].

In fact, the risk of reactivation is estimated at around 10%-50% for HBsAg-positive patients undergoing chemotherapy[76,77], while different percentages have been reported in HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive patients and in inactive HBV carriers,from 2% to 41.5%[68,78-82], Consequently, it is mandatory to identify the hematooncological patients at risk of reactivation who need antiviral treatment, either in prophylaxis or as pre-emptive therapy. In fact, various guidelines[51,76,83], controlled clinical trials[84,85]and meta-analyses[86,87]have shown that in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy, nucleo(t)side analogs reduce the incidence of HBV reactivation and the frequency of associated hepatitis and death for liver failure[88].

Allogeneic autologous HSCT is another eventuality characterized by a high risk for HBV reactivation. Published data are still limited, but a study on 32 HBsAg-positive patients with NHL undergoing high-dose chemotherapy and autologous HSCT reported a symptomatic acute exacerbation in 50% of cases[89]. In patients with occult HBV infection the risk could be lower, because in allogeneic HSCT, donor vaccination including that against HBV can result in the transfer of immunity against infectious antigens, thus reducing the risk of HBV reactivation[90]. Finally, the development of graft-vs-host disease significantly increases the risk of HBV reactivation due to the immunosuppression therapy administered and to the delay in the reconstitution of the immune system[91].

Immunosuppressive regimens

The risk of HBV reactivation has been graded in relation to the different immunosuppressive treatments as follows: (1) High risk: Greater than 10%reactivation (rituximab and other anti-CD20-directed monoclonal antibodies;doxorubicin and other drugs of systemic cancer chemotherapy); (2) Moderate risk:Between 1%-10% (imatinib, ibrutinib and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors;corticosteroids at a daily dose of ≥ 20 mg for ≥ 4 wk); (3) Low risk: Less than 1%(azathioprine, methotrexate and other traditional immunosuppressive agents;corticosteroids for ≤ 4 wk).

RISK FACTORS FOR HBV REACTIVATION IN DIFFERENT IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE REGIMENS

Cancer chemotherapy

A study on patients with lymphoma treated with different chemotherapy regimens reported HBV reactivation in 48% of 27 HBsAg-positive patients and in 4% of 51 HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive[82]. It has also been reported that this reactivation occurred more frequently in patients receiving anthracycline-derived chemotherapeutic drugs, such as doxorubicin and epirubicin, than in those treated with other chemo-therapy regimens[92].

Corticosteroids

The evidence that corticosteroids may enhance HBV replication was first reported by Sagnelli et al[93]in 1980 and subsequently confirmed in several other investigations.More recently a glucocorticoid-responsive-transcription regulatory element has been identified in HBV genome which, up-regulated by corticosteroids, may induce increased viral replication and a direct suppressive effect on cytotoxic T cells involved in HBV control[94]. Corticosteroids are often associated with other chemotherapy agents in patients with hemato-oncologic disorders, with an additive deleterious effect. To better understand the role of corticosteroids in such associations, 50 NHL patients with HBsAg-positive underwent chemotherapy regimens had an higher incidence of HBV acute exacerbation than patients treed with with corticosteroid[95].

Monoclonal antibodies

Treatment of onco-hematologic diseas es with monoclonal antibodies in patients with overt or occult HBV infection is associated with the risk of viral reactivation, which may induce severe or fatal hepatic failure[96]. This risk is particularly high when HBsAg-positive patients are treated with anti CD20 antibodies, such as rituximab,ofatumumab and obinutuzumab, commonly used to treat B-cell malignancies due to the effective elimination of B cells from blood, lymphatic system and bone marrow,which may induce HBV reactivation in 16.9% of treated cases with rituximab[97].Patients with occult HBV infection have a lesser risk of HBV reactivation, which occurs in about 8% of cases[98]. In this context, subjects with occult HBV infection positive with anti-HBc and anti-HBs show a reduced risk of HBV reactivation, due to a protective role of anti-HBs[99]. HBV-reactivation occurring more than two years after the use of rituximab.

Alemtuzumab, a monoclonal antibody against CD52 used for refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) caused reverse HBsAg seroconversion and symptomatic reactivation in patients with occult HBV infection[100]. This event was observed even for newer monoclonal antibodies, namely mogamulizumab, a treatment for T-cell lymphoma, and brentuximab vedotin, used to treat Hodgkin's lymphoma[101,102]. Also Daratumumab, a monoclonal antibody against CD38, over-expressed in B-cell hematologic malignancies, may have the same potential effect, but no reports have emerged to date to this regard

New drugs

Attention should be paid to the risk of HBV reactivation in the new treatment regimens for multiple myeloma and CLL, since published data on the topic are scanty.Tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib and nilotinib are used for effective immunosuppressive action, which, however, implies the possibility of HBV reactivation[103].

Idelalisib (PI3K tyrosine kinase inhibitor), brutinib (bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor) used to treat CLL and certain NHLs, have been found to be responsible for cases of HBV reactivation. Similar observations have been made for ruxolitinib(inhibitor of Janus-activated kinases-JAK) used to treat myelofibrosism, and for bortezomib (proteasome inhibitor) in multiple myeloma[104,105].

Venetoclax, a small molecule inhibitor of BCL-2 used in refractory cases of CLL may have a potential risk of HBV reactivation, but no case has been signaled to date.The same consideration also applies to azacitidine and decitabine, hypomethylating agents used to treat acute myeloid leukemia.

It has also been suggested that treatment of cancer with antibody immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-CTLA4 tremelumab and ipilimumab; anti-PD-L1:Nivolumab and pembrolizumab; PD-L1: durvalumab, atezolizumab and avelumab) is a risk factor for HBV reactivation, to be prevented by anti-HBV prophylaxis[67,106-109].

MANAGEMENT OF HBV REACTIVATION IN AN ONCOHEMATOLOGICAL SETTING

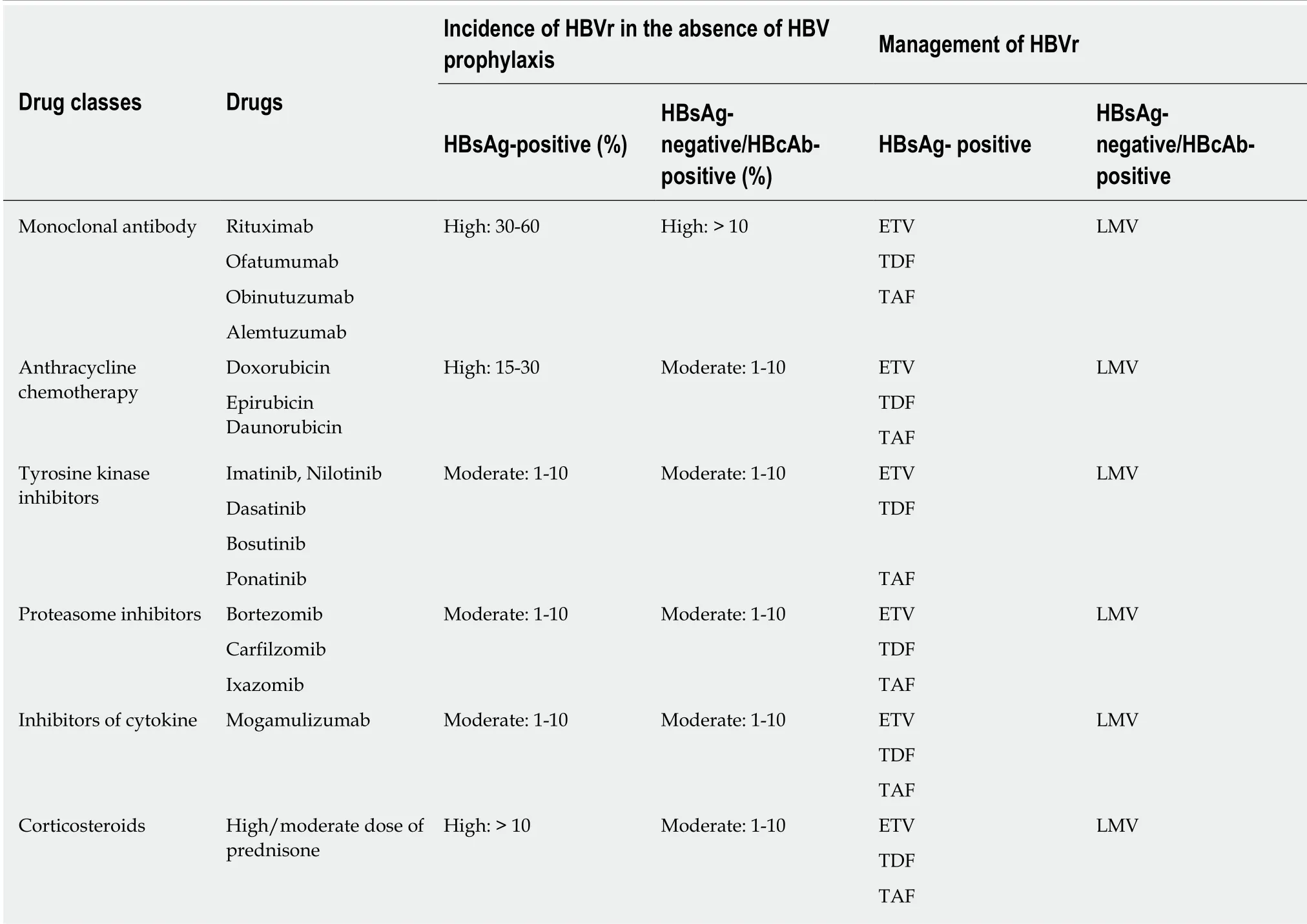

Nucleo(t)side analogues should be administered to all patients with a high/moderate risk of HBV reactivation undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, as therapy to the HBsAg-positive (regardless of HBV DNA levels) and as prophylaxis to HBsAgnegative and anti-HBc-positive cases[51,88]. The risk of HBV reactivation is associated with HBV serological status (HBsAg positivity or HBsAg negativity and anti-HBc positivity with/without anti-HBs positivity) and with the immunosuppression level obtained with the drug administered (Table 1).

As in clinical practice, patients with HBsAg-positivity and serum HBV DNA ≥ 2000 IU/ml and increased ALT serum values (active carriers) should start long-term antiviral therapy with NAs, namely ETV, TDF or TAF, according to international guidelines[67,107]. Inactive HBsAg carriers with HBV DNA < 2000 IU/mL, normal ALT and AST and no sign of liver cirrhosis are at risk of HBV reactivation under immunosuppressive therapy and should receive a prophylaxis with ETV, TDF or TAF, drugs with a high genetic barrier to resistance. Although effective for the prevention of HBV reactivation, lamivudine is not indicated in the last two settings mentioned because of its low genetic barrier to viral resistance and to a residual risk of HBV reactivation in approximately 10% of cases treated[51].

In fact, Huang et al[108], in a randomized controlled trial, comparing the efficacy of ETV versus LAM in prophylaxis the reactivation of HBV infection in diffuse large Bcell lymphoma patients with HBsAg-positivity undergone R-CHOP chemotherapy(rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) observed that ETV is more effective than LAM, reducing the risk of HBV reactivation (6.6% vs 30%),HBV-related hepatitis (0% vs 13.3%), and chemotherapy discontinuation (1.6% vs 18.3%).

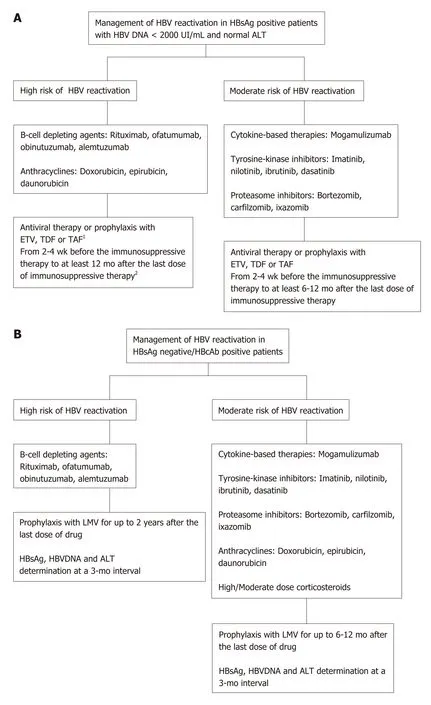

While there is agreement in the literature on the fact that all HBsAg-positive patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy should be assigned to pharmacologic therapy or prophylaxis, in the case of HBsAg-negative/hepatitis B core antibodies-positive patients two strategies have been adopted to prevent HBV reactivation: prophylaxis or pre-emptive antiviral therapy. Also, the international guidelines are divided on the type of management for these latter patients (Figure 1).For example, for rituximab-based therapy, routine prophylactic antiviral therapy is recommended by several guidelines[51,107,109,110]. However, it is advisable for HBsAgnegative/anti-HBc-positive patients with HBV-DNA levels detectable before starting immunosuppressive therapy to use the same prophylactic regimen (with ETV, TDF or TAF) adopted for HBsAg-positive patients[111]. Lamivudine may be used only for antiviral prophylaxis in non-viremic patients with resolved HBV infection[112]. In fact, a meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials comparing lamivudine prophylaxis to the pre-emptive strategy (treatment at the beginning of viral reactivation)[80,84,85,97,113-115]showed that antiviral prophylaxis is more effective. Thus, the preemptive strategy could be used only in cases at a very low risk of HBV reactivation,and, consequently, it should not be used in an onco-hematologic setting, where patients are treated with combination chemotherapies conferring a high risk of HBV reactivation.

Table 1 lncidence of hepatitis B virus replication in hemo-lymphoproliferative diseases and related management, according to hepatitis B virus markers and type of immunosuppressive regimens

It is commonly accepted that an antiviral regimen should be started 2-3 wk before immunosuppressive treatment and that it should last throughout the whole immunosuppressive treatment and, thereafter, throughout the whole prophylaxis;periodical controls including physical examination, serum liver enzymes, HBsAg and HBV DNA should be performed at a 3-monthly interval[116].

The correct duration of pharmacological prophylaxis remains controversial. Of course, antiviral therapy should not be discontinued in patients with chronic hepatitis B or cirrhosis, regardless of the duration of chemotherapy. In inactive carriers,antiviral prophylaxis should cover the entire period of immunosuppressive treatment and an additional period of 12-18 mo after the discontinuation of the immunosuppressive regimen, to be extended to 24 mo if chemotherapy had included rituximab or other anti-CD20 antibodies[51]. The rationale for this extension is that immune recovery may be delayed due to deep immunodepression exerted by rituximab or its analogues[67,117]. In fact, Yamada et al[118]described a case of HBV reactivation emerging over the third year after the discontinuation of R-CHOP therapy; in this case HBV-DNA monitoring had been stopped 18 months after chemotherapy was discontinued. The same authors also reviewed the literature data on the topic and concluded that an advanced age, lymphoid malignancies, multiple courses of rituximab-containing therapies were all common features in cases of late reactivation.

Figure 1 Management of hepatitis B virus reactivation. A: Management of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive patients with HBV DNA < 2000 UI/mL and normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT); B: Management of HBV reactivation in HBsAg negative/hepatitis B core antibodies positive patients. 1HBsAg, HBV DNA and ALT determination at a 3-mo interval; 2In patients treated with rituximab or other cell-depleting agents, the anti-HBV prophylaxis should be continued for up to 2 years after the last dose of drug. HBV:Hepatitis B virus; HBVr: Hepatitis B virus replication; HbsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HbcAb: Hepatitis B core antibodies; ETV: Entecavir; TDF: Tenofovir; TAF: Tenofovir alafenamide; LMV: Lamivudine; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase.

In patients with resolved HBV infection, lamivudine prophylaxis should cover the entire period of immunosuppressive treatment and, thereafter, an additional period of 18-24 mo as delayed episodes of HBV reactivation have been reported[51,76,119]. In fact,Marrone et al[119]described HBV reactivation in 3 (4%) of 68 patients with oncohematological disease (two with CLL and one with Waldenstrom's disease) occurring 1-7 mo after discontinuation of lamivudine prophylaxis that had covered the whole period of immunosuppressive treatment and a subsequent 18 mo after.

Particular attention should be paid to the recipients of HSCT, a condition involving much deeper immunological suppression, for whom the duration of antiviral therapy has not yet been established. In these cases, HBV reactivation occurred years after the transplant, as in the anecdotal case of a patient who was anti-HBs-positive at baseline and had HBV reactivation 4 years after transplantation[120]. For this special population the duration of a long-term antiviral therapy has not yet been established by the international guidelines and, in the meantime, lifelong treatment may be wiser[116].

Overall, the most suitable duration of monitoring for early identification of HBV reactivation after antiviral withdrawal remains partially undefined, depending on several factors, among which the degree of immunosuppression that predominates.Therefore, it is prudent that this decision be reserved for skilled clinicians who will use international guidelines, results from specialized literature and clinical and laboratory data obtained during the entire period of observation.

CONCLUSION

Reactivation of HBV replication has a negative impact on the clinical course of patients with hemo-lymphoproliferative malignancies, because of its significant morbidity and its potential to induce a worse prognosis, or even a fatality. However,no shared effective solution has been decided worldwide to date, nor has a uniform standard of screening, treatment or prevention been established. Given the efficacy of nucle(t)side analogues against HBV, administered as treatment or prophylaxis is reported for the patients at risk. All patients should be evaueted for serum HBsAg,anti-HBc antibody, HBV DNA and liver enzymes before any immunosuppressive therapy is initiated. In recent years, national and international guidelines have recommended HBV screening before starting chemotherapy. The risk posed by individual treatment regimens should be carefully assessed to establish the need for antiviral prophylaxis or treatment and the duration of antiviral drug administration.For the patients identified as requiring antiviral treatment or prophylaxis, anti HBV nucleoside/nucleotide analogues with a high genetic barrier to viral resistance is recommended, especially for those at a high risk of HBV reactivation and when longterm immunosuppressive treatment is planned.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Diuretic window hypothesis in cirrhosis: Changing the point of view

- Fluoroquinolones for the treatment of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in liver transplantation

- Current status of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with surgically altered anatomy

- Choledochal cysts: Similarities and differences between Asian and Western countries

- Gastro-duodenal disease in Africa: Literature review and clinical data from Accra, Ghana

- Screening of aptamers and their potential application in targeted diagnosis and therapy of liver cancer