Update on hepatocellular carcinoma: Pathologists' review

2019-05-08TonyElJabbourStephenLaganaHwajeongLee

Tony El Jabbour, Stephen M Lagana, Hwajeong Lee

Abstrac t Histopathologic diversity and several distinct histologic subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are well-recognized. Recent advances in molecular pathology and growing knowledge about the biology associated with distinct histologic features and immuno-profile in HCC allowed pathologists to update classifications. Improving sub-classification will allow for more clinically relevant diagnoses and may allow for stratification into biologically meaningful subgroups. Therefore, immuno-histochemical and molecular testing are not only diagnostically useful, but also are being incorporated as crucial components in predicting prognosis of the patients with HCC. Possibilities of targeted therapy are being explored in HCC, and it will be important for pathologists to provide any data that may be valuable from a theranostic perspective. Herein, we review and provide updates regarding the pathologic sub-classification of HCC.Pathologic diagnostic approach and the role of biomarkers as prognosticators are reviewed. Further, the histopathology of four particular subtypes of HCC:Steatohepatitic, clear cell, fibrolamellar and scirrhous - and their clinical relevance, and the recent consensus on combined HCC-cholangiocarcinoma is summarized. Finally, emerging novel biomarkers and new approaches to HCC stratification are reviewed.

Key words: Hepatocellular carcinoma; Subtype; Classification; Review; Update

INTRODUCTION

Hep atocellular neop lasms constitute a heterogeneous group of d isord ers that encompasses benign, dysplastic and malignant lesions. These lesions d emonstrate a w id e morphologic sp ectrum and includ e new ly id entified morp hologic subtyp es.Know led ge about molecular signatures, p rovisional classifications, and clinical correlates continues to evolve. A careful synthesis of all clinical, rad iologic and pathologic data is essential to establish a proper diagnosis and d evise a treatment plan.

This review aims to ad d ress the most common questions brought to our(pathologists') attention by our clinical colleagues. Firstly, the current classification of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) w ill be review ed. Secondly, the utility of ancillary tests to include immunohistochemistry (IHC) includ ing prognostic biomarkers, and molecular testing w ill be review ed. Next, a few subtypes of non-conventional HCC that are d eemed clinically relevant w ill be briefly review ed. Further, w e w ill summarize the recent consensus on combined HCC-cholangiocarcinoma (cHCCCCA). Finally, novel diagnostic and/or prognostic biomarkers and comp rehensive genomic and epigenomic stratification of HCC are briefly reviewed.

EVOLUTION OF THE HISTOLOGIC (MORPHOLOGIC)CLASSIFICATION OF HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

The 4th edition of WHO classification of the tumors of the digestive system was published in 2010. In this edition, in addition to the conventional HCC, the WHO recognized 5 morp hological subtypes of HCC: Fibrolamellar HCC (FL-HCC),scirrhous HCC (S-HCC), und ifferentiated carcinoma, lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma and sarcomatoid HCC. Several architectural grow th patterns and cytological variation of HCC were also described to aid in establishing a diagnosis.These architectural and cytologic variations were not recognized as ind ividual subtypes. The following architectural patterns were described: trabecular (plate-like)pattern, pseudoglandular (acinar) pattern and compact pattern. The cytological variations included pleomorphic cells (bizarre multinucleated, mononuclear giant cells or osteoclast-like giant cells), clear cells, fatty change, bile production, hyaline bodies (Mallory-Denk bodies), pale bodies and ground glass inclusions[1].

Since the publication of the 4th edition WHO classification of the tumors of the digestive system, additional morphologic variations of HCC have been reported in the literature, some with characteristic molecular signature. It was suggested that for a tumor with specific morphologic variation to qualify for a subtype, the following criteria should be met: the tumor should have reproducible microscopic pattern,immuno-histochemical and molecular tests that help in the subcategorization of the tumor should be available, and there should be a particular clinical correlate regarding the proposed subtype.

This ap proach has led to 12 proposed subtyp es and 6 p rovisional entities,constituting approximately 35% of HCC. In a decreasing order of frequency, these morphologic subtypes are: Steatohepatitic, clear cell, scirrhous, cirrhotomimetic,fibrolamellar carcinoma, combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma, combined hepatocellular and neuroendocrine, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor producing,sarcomatoid, carcinosarcoma, carcinosarcoma w ith osteoclast-like giant cells and lymphocyte rich. Out of the 6 provisional entities, chromophobe subtype is the most common. The remaining 5 provisions are of equal frequency: Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma with stem cell features, lipid rich, myxoid, syncytial giant cell and transitional cell[2,3]. A subset of the proposed subtypes and provisional entities is likely to be endorsed in the 5th edition WHO classification of the tumors of the digestive system, which is to be released in 2019.

ROLE OF IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY IN HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA DIAGNOSIS

Both w ell d ifferentiated and poorly d ifferentiated hepatocellular neoplastic lesions pose diagnostic challenge. “Well differentiated” implies that the histomorphology of the tumor closely resembles the native tissue the tumor originates from. Therefore, a w ell d ifferentiated HCC recapitulates benign liver tissue, mimicking the follow ing benign and pre-neoplastic entities: hepatocellular adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia(FNH), regenerative nod ule, and d ysp lastic nod ule in cirrhotic liver. In ord er to demonstrate malignancy in a well-differentiated HCC that morphologically resembles benign hepatocytic lesions, IHC such as CD34 (show ing d iffuse sinusoid al capillarization), and a panel of glutamine synthetase (GS), glypican-3 (GPC-3) and heat shock protein 70 (HSP-70) may be helpful[4,5]. Reticulin special stain remains a very useful test, as the aforementioned benign and pre-neoplastic entities generally retain a reticulin network, whereas HCC does not.

However, these stains are neither 100% specific nor 100% sensitive[6]. Thus, careful review of histomorphology and stringent application of cytomorphologic criteria of malignancy, and clinical and imaging correlation is essential to establish a firm d iagnosis of w ell-differentiated HCC. For examp le, w hen immuno-histochemical stains are not helpful in demonstrating malignancy, focal loss of reticulin framework in conjunction w ith cytomorp hologic features of malignancy may be the only ad junctive in arriving at the d iagnosis. Yet, d ifferentiating betw een high grad e d ysp lastic nod ule and small, early w ell-d ifferentiated HCC may be extremely challenging in a biopsy specimen[7].

At the other end of the spectrum, “poor differentiation” implies that a tumor lacks resemblance to the native tissue that the tumor originates from. Consequently, a poorly d ifferentiated HCC w ould morphologically resemble poorly d ifferentiated carcinomas (malignancy of epithelial origin) from any other site, including metastasis to the liver and poorly differentiated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. While it would be relatively straightforw ard to d ocument malignancy based on histomorp hology,d ocumenting that the tumor d emonstrates immuno-histochemical evid ence of hepatocellular phenotype, and excluding other lines of differentiation are necessary in arriving at the correct d iagnosis of HCC. Several immuno-histochemical markers includ ing hep atocyte in p araffin 1 (Hep Par1), Arginase-1, CD10, p olyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen, bile salt export pump and GPC-3 have been utilized in this setting w ith variable sensitivities and sp ecificities d ep end ing on the d egree of differentiation of HCC[3,4,7,8]. One study suggested that a combination of Arginase 1 and GPC-3 has the highest sensitivity in determining a hep atocellular origin of a poorly differentiated carcinoma[9].

Some HCCs aberrantly express non-hepatocellular immuno-histochemical markers of origin and further confound the d iagnosis. Shah et al rep orted that CDX2, an immuno-histochemical marker indicative of intestinal origin, is expressed in 5.2% of HCCs. In their cohort, the aberrant CDX2 exp ression w as common in p oorly differentiated HCC[10]. Also, aberrant CK20 expression has been d escribed in 14% of HCCs[11]. Furthermore, a case of poorly d ifferentiated HCC co-expressing CDX2 and CK20 has been recently rep orted[12]. This w ould pose a d iagnostic pitfall especially when metastatic colorectal carcinoma is a clinical and radiologic differential diagnosis for a liver mass.

Likew ise, CK7 expression in HCC is not uncommon. Ward et al compared the immuno-histochemical profile of 22 cases of FL-HCC and 50 non-FL type HCC using tissue microarrays. When “positive” w as defined as > 15% of tumor cells staining and“focal positive” as < 15%, 28% and 32% of non-FL type HCC were positive and focal positive for CK7, respectively. All FL-HCCs w ere positive for CK7[13]. Albumin in situ hybridization (Albumin-ISH) is another promising test. Albumin-ISH is positive in tumors of liver origin such as HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma w ith > 95%and 80%-95% sensitivity, resp ectively, and is negative in metastatic tumors to the liver[3,8,14].

MOLECULAR BASIS OF HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA AND TARGETED THERAPY

Identification of molecular alterations and signaling pathways that are involved in tumorigenesis is critical for personalized medicine. In HCC, however, it is challenging to identify genetic alterations that are directly related to tumorigenesis, as HCC usually arises in a background of chronic liver disease of many years. The ongoing inflammation and injury lead to the accumulation of a multitude of genetic alterations p rior to the d evelop ment of HCC. The alterations d iffer betw een p atients w ith different und erlying liver diseases, and betw een tumor foci w ithin a same patient.This p henomenon is know n as “field effect”, and is consid ered an obstacle in developing a therapy targeting a single mutation[15].

Several stud ies attempted to classify HCCs according to their molecular signature,but the attempts have not been successfully ad op ted in the clinical practice[16-19].How ever, these attemp ts are making a significant progress in id entifying distinct morp hologic subtyp es corresp ond ing to sp ecific molecular profiles and clinical correlates. For example, scirrhous subtype, one of the histologic subtyp es that were recognized in 2010 WHO, is associated with TSC1/TSC2 mutations. Also, the authors recognized new morp hological subtyp e, “macrotrabecular-massive” subtyp e,associated w ith TP53 mutations, FGF19 amplifications and w ith poor survival and high serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level[20].

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network analyzed a total of 559 cases of HCC,and identified 26 genes with significant alterations including some that are promising therapy targets. This study also showed that the promotor region of TERT (regulating cell survival), TP53 (a gene that is frequently involved in carcinogenesis), or CTNNB1(regulating cell growth and differentiation) is altered in 77% of HCC. How ever, the authors recognized that it is unlikely to have one therap eutic agent that w ould effectively target most HCC, given the variety of mutations identified in a given patient (requiring a combination of treatments to target different mutations)[21].

Sorafenib is one of the first generation fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitors approved for the first-line treatment of advanced HCC. Several protocols and clinical trials rep orted mod est results w ith survival benefit, esp ecially in p atients w ith hepatitis C[22-24]. Other multikinase inhibitors, regorafenib and cabozantinib, also show ed survival benefit as a second-line treatment compared to placebo group in p hase 3 clinical trials[23,25,26]. Recent p hase 1/2 trial of nivolumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, in patients w ith ad vanced HCC w ith or w ithout chronic viral hepatitis reported promising responses[27].

PATHOLOGIC PROGNOSTIC BIOMARKERS

Variable parameters such as serum AFP level, des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin level,tumor size and number, margin status, major vessel invasion, tumor stage,Edmonson-Steiner grade, Child-Pugh score, portal hypertension and cirrhosis, are considered clinical prognosticators of HCC, depending on the treatment modalities and underling liver diseases[28-32]. Pathologically, the overall poor outcome of HCCs expressing stem cell markers such as keratin 19 (K19), epithelial cell adhesion molecule (Ep CAM), and CD133 has been reported, potentially via hypoxia-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition[33-36]. For example, the expression of K19 was associated with high rate of recurrence following radiofrequency ablation, and the HCCs expressing K19, Ep CAM or carbonic anhydrase-IX (marker of hypoxia) showed incomplete response to transarterial chemoembolization. The overexpression of CD133 and CD90 in HCCs predicted poor response to sorafenib[37-39]. Histologic grade of HCC is useful in predicting long-term survival. In HCCs with different grades of tumor foci within a same lesion, the worst grade within the tumor appears to dictate its biologic behavior. Therefore, careful approach is warranted when dealing with limited biopsy sample[40].

SELECTED SUBTYPES OF HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

Steatohepatitic HCC

A possible correlation betw een non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and the development of HCC has long been recognized[41]. Moreover, it has been documented that HCC arising in association w ith non-alcoholic steatohep atitis or metabolic syndrome can develop in non-cirrhotic livers[42,43].

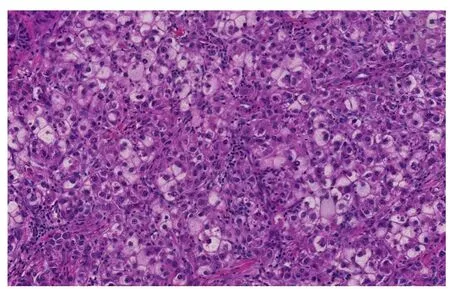

A steatohepatitic variant of HCC was d escribed in 2010. In this study, the authors described multiple histologic features that can be seen in steatohepatitis includ ing macrovesicular steatosis, ballooning, Mallory-Denk Bod ies, inflammation and pericellular fibrosis in 35.5% (22 of 62) of HCC arising in HCV ind uced cirrhosis.63.6% of patients w ith steatohep atitic HCC had risk factors of NAFLD (Figure 1).Furthermore, 63.6% of steatohepatitic HCC was associated w ith background NAFLD,suggesting a link betw een this variant of HCC and NAFLD[44]. Subsequently the same group established a correlation betw een the steatohep atitic variant HCC and an und erlying steatohep atitis or metabolic risk factors, and suggested a role of steatohepatitis in human hepatocarcinogenesis[45]. A minor subset of steatohepatitic HCC may arise in the absence of background fatty liver d isease or metabolic synd rome[46]. This histologic entity and the reports of HCC arising in non-cirrhotic steatohep atitis gained the attention of hep atologists and oncologists. With the increasing incidence of metabolic risk factors and NAFLD especially in the w estern world, recognition of steatohepatitis w ithout cirrhosis as an additional risk factor for HCC could have significant bearing on HCC screening programs[41,47].

The molecular p rofile and the p athw ay involved in the carcinogenesis of steatohepatitic subtype are different from conventional HCC. For example, CTNNB1 mutation (beta catenin pathway alterations) are less frequent in steatohepatitic HCC compared to conventional HCC[48]. The immune-histochemical p rofile of steatohep atitic HCC has been comp ared to the conventional type. While no significant differences in staining pattern w ith HNF-1α, β-catenin, GS, GPC-3 and HSP-70 w ere seen betw een the tw o, the d egree of staining w ith C-reactive p rotein and serum amyloid A w as higher in steatohepatitic HCC[49].

FNH arising in a background of steatotic liver may d emonstrate at least focal,steatohepatitis-like features and mimic steatohepatitic HCC. Careful identification of the typical histologic features of FNH including thick w alled blood vessels, ductular reaction and thick fibrous septa, will be helpful in ruling out a steatohepatitic HCC[50].A stud y conducted on a Japanese population showed that steatohepatitic HCC has a similar prognosis to conventional type[51].

Clear cell HCC

Cytoplasmic clearing is a defining feature of the broad category of neoplasms so called “clear cell tumors”. It may be a consequence of accumulation of glycogen,cytop lasmic vesicles, lip op olysaccharid es or mucop olysaccharid es, or simp ly represent a processing artifact[52]. Clear cell HCC is a w ell d ifferentiated variant of HCC. Its cytoplasmic clearing is a result of glycogen and less frequently, fat storing in the cytop lasm[53]. The minimum amount of neop lastic cells w ith clear cytop lasm required for the diagnosis of clear cell HCC varies in the literature; however a cut-off of minimum 50% has been advocated in the recent AFIP fascicle[3].

Rarely, clear cells may be seen in other types of HCC, i.e., clear cell variant of fibrolamellar HCC or lip id-rich HCC second ary to cytoplasmic lipid accumulation.Thus, assigning the right subtype for the tumor in question may be necessary but challenging, particularly w hen there is a difference in the outcome[54]. Most stud ies comparing the prognosis of clear cell HCC versus conventional HCC showed a better prognosis of the former[55,56], or at least similar outcomes for both[57,58]. Interestingly,Lee et al[59]reported the presence of IDH1 mutation in 25% of clear cell HCC. These IDH1 mutated clear cell HCCs show ed a statistically significant w orse prognosis comp ared to IDH1 w ild-type clear cell HCCs. Of note, IDH1 mutations are not uncommon in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, a tumor with a significantly w orse prognosis than HCC[60,61].

Cases of clear cell HCC in non-cirrhotic liver or liver without hepatitis are rarely reported in the literature[62,63]. Therefore, w hen a liver tumor with clear cell features in an otherw ise unremarkable background liver is encountered, a metastasis from another p rimary w ith clear cell components needs to be exclud ed. Most common scenario w ould be a metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma or a clear cell carcinoma from the ovaries mimicking clear cell HCC. While a p anel of IHC w ill aid in establishing the diagnosis of a primary vs a metastatic process in the vast majority of cases[64-66], some ovarian clear cell carcinomas may stain w ith Hep Par-1, p osing a diagnostic pitfall[65].

Fibrolamellar HCC

FL-HCC is a clinically, histologically and molecularly distinct subtype of HCC when compared to other subtypes of HCC. It frequently occurs in adolescents and young adults, and the mean age at the diagnosis is 25[67-69]. The background liver typically lacks features of chronic hepatitis, inflammation, fibrosis, or preneoplastic lesions.Primarily due to the absence of cirrhosis in the background, the outcome of FL-HCC is usually better than the remaining subtypes. When non FL-HCCs arising in noncirrhotic liver are compared, both show a similar outcome[70].

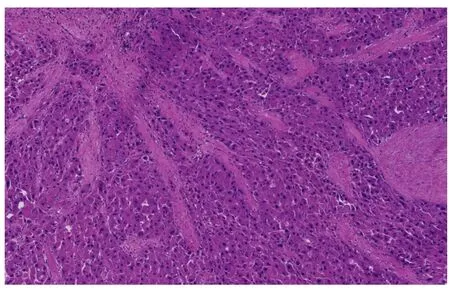

The unique histology of FL-HCC was first described in 1956. FL-HCC consists of large, polygonal eosinophilic cells with abundant cytoplasm resembling hepatocytes.There are prominent nucleoli and pale inclusion bodies and pink bodies (hyaline bodies/globules) within the neoplastic cells, and the extensive intratumoral fibrosis is a characteristic feature. The thick collagenous bands within the tumor are often parallel and “lamellar”, but may be irregular and haphazard[71](Figure 2). Patchy areas of solid growth with little fibrosis may be noted within FL-HCC[3]. Intratumoral cholestasis is common, and pseudoglandular growth with mucin production may be seen, mimicking combined cholangiocarcinoma component[3].

Figure 1 Steatohepatitic hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumoral cells show features of steatohepatitis including steatosis, ballooning and Mallory-Denk bodies (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 200).

The immuno-profile of FL-HCC is also unique, and shows positivity for the biliary marker CK7[13]and histiocytic marker CD68[72]. Histologic differential diagnosis is SHCC. Both are characterized by extensive intratumoral fibrosis. Kim et al[73]studied the nature of the fibrous stroma in FL-HCC and S-HCC. The authors showed that the fibrous stroma in FL-HCC is comp osed of dense lamellated collagen w hereas in SHCC, the fibrous stroma represents aggressive and complex tumoral microenvironment enriched by cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor-infiltrating macrophages.At the molecular level, FL-HCC harbors a characteristic fusion of DNAJB1 and PRKACA on chromosome 19, secondary to chromosomal d eletion in betw een these tw o genes[74]. This fusion has been p roven to be 100% sp ecific for FL-HCC in the context of hepatic malignancy[75].

Scirrhous HCC

S-HCC is another rare subtype of HCC. The histomorphology of S-HCC is somewhat similar to FL-HCC with striking intratumoral fibrosis and oftentimes non-cirrhotic background liver. While the biologic behavior of S-HCC may be more aggressive than usual HCC with more portal vein invasion in the former, the long term outcome and prognosis of S-HCC is similar to, or better than those of usual HCC[3,76].

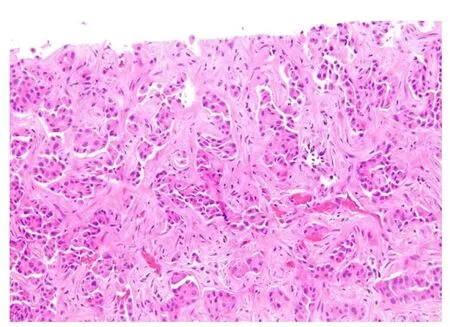

The fibrosis involves at least 50% of the tumor and separates small nests of tumor cells[2](Figure 3). Due to the abundance of intratumoral fibrous stroma associated with thin trabecular pattern growth, S-HCC may, radiologically and pathologically, closely mimic cholangiocarcinoma[3,76,77]. S-HCC is positive for CK7 similarly to FL-HCC[78].However, the distinction between these two can be made by co-expression of CD68[72]and the fusion of DNAJB1-PRKACA genes in FL-HCC[74]. On the other hand,TSC1/TSC2 mutations and the overexpression of TGF-beta signaling have been identified in S-HCC[20,79]. While S-HCC is a subtype of HCC, immuno-markers that are associated with adenocarcinoma such as CK7 and Ep CAM are commonly expressed whereas Hep Par1 expression is less common in S-HCC. A combination of GPC-3 and Arginase 1 was useful in distinguishing S-HCC from cholangiocarcinoma with 100%sensitivity for S-HCC[80].

COMBINED HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMACHOLANGIOCARCINOMA

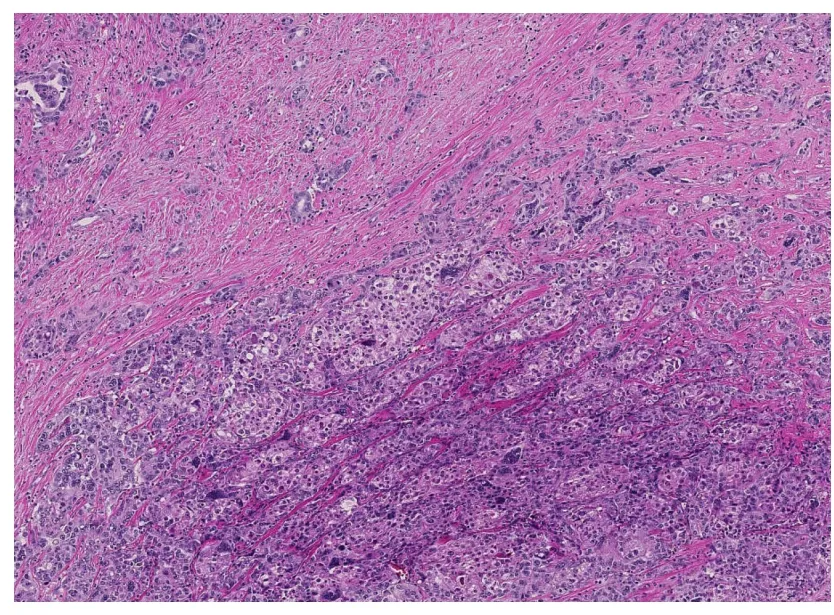

cHCC-CCA is p rimary liver cancer d emonstrating morp hologic and immunohistochemical features of both HCC and CCA (Figure 4). Collision tumor or tw o separate primaries of HCC and CCA in the same liver do not qualify for cHCC-CCA d iagnosis. Variable terminologies have been used in the literature for this entity,includ ing hepatocholangiocarcinoma, biphenotyp ic HCC-CCA, mixed HCC-CCA,mixed hepatobiliary carcinoma, combined liver cell and bile duct carcinoma, HCC w ith d ual p henoty p e, HCC w ith stem/p rogenitor cell immunop henotyp e,cholangiolocarcinoma, cholangiolocellular carcinoma (CLC), intermed iate HCC and stem cell tumor, making it difficult to collect meaningful data[3,81].

In 2010 WHO, cHCC-CCA w as largely divided into two types: Classical type and a subtyp e w ith stem-cell features, w herein the latter w as further subd ivid ed into typical, intermediate, and cholangiocellular subtypes[1]. How ever, subsequent studies showed that stem cell features are seen in many other types of HCC and CCA and the WHO criteria for stem cell subtypes are difficult to apply in practice. This observation has led to collaborative efforts and the publication of a consensus paper on working terminology and diagnostic criteria of cHCC-CCA in 2018 by international experts in the field consisting of pathologists, radiologists and clinicians[81].

Figure 2 Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Multiple fibrous septa composed of parallel collagen fibers separate tumoral trabeculae (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 100).

The consensus p ap er formally end orsed the terminology c HCC-CCA and recommend ed that the d iagnosis of cHCC-CCA has to be p rimarily based on morphology on hematoxylin and eosin stain and immuno-histochemical stains are to be used as a supplemental purpose only. In add ition, the panel recommended the term "intermediate cell carcinoma" for previous cHCC-CCA with "intermediate cell"stem cell features (primary liver cancer consisting purely of intermediate cells), as a separate entity. "CLC" w as recommended as another separate entity w ith a cut off of 80% required for the d iagnosis of p ure CLC w ithout mixed comp onents. It w as recommended that the morphologic and immuno-histochemical stem/progenitor cell features/phenotypes are to be noted in a comment, but not in the d iagnostic line.Further, w hen more than one morphologic component is present w ithin the same tumor, it was recommended that each component to be listed in the diagnostic line.Therefore, previous cHCC-CCA w ith "typical" and "cholangiolocellular" stem cell features are termed as cHCC-CCA and cHCC-CCA-CLC, resp ectively, and the percentage of each component is to be reported[81].

Stud ies suggest that cHCC-CCA is likely a clonal lesion of stem/progenitor cell origin[33,82,83]. The molecular phenotyp e of cHCC-CCA is heterogeneous[84]; how ever,molecular features ind icative of stem cell features have been d ocumented[85].According to the current 8th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer cancer staging manual, cHCC-CCA is staged as intrahep atic CCA[86]. Given the d iffering treatment options for HCC and CCA, biopsy sample of a large mass lesion needs to be interp reted w ith great caution and a resection sp ecimen need s to be thoroughly sampled.

EMERGING BIOMARKERS AND COMPREHENSIVE STRATIFICATION OF HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

Novel diagnostic and/or prognostic biomarkers are emerging as key players in the field of HCC research. For example, annexin A2 is significantly increased in the serum of patients with HCC when compared to patients with chronic liver disease, thus may be d iagnostically useful especially w hen combined w ith AFP[87,88]. Add itional biomarkers, such as osteopontin, Golgi protein-73, squamous cell carcinoma antigen,soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor, midkine, AXL, thioredoxins[88],multifucosylated α-1-acid glycoprotein[89], vascular end othelial growth factor,angiopoietin[90], survivin[91]and alpha-1 antitrypsin[92], have shown potential for diagnostic and/or prognostic utility. Some of these are recognized by a major international hepatology society[90].

Likewise, comprehensive genomic and epigenomic approaches are emerging as promising tools to stratify HCCs into clinically relevant subgroups. Bidkhori et al[93]stratified HCCs into three subtypes: Altered kynurenine metabolism, WNT/βcatenin-associated lipid metabolism and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling subtype based on the metabolic and signalling pathw ays and show ed differences in survival.Shimada et al[94]stratified HCCs into three major subtypes: Mitogenic and stem celllike tumors w ith chromosomal instability (the proliferative subtyp e), CTNNB1-mutated tumors d isplaying immune suppression and metabolic disease-associated tumors by multi-platform analysis including transcriptome, exome and methylome profiles and public omics data, and show ed a favorable p rognosis in the "immunogenic" subset of the metabolic disease-associated tumors.

Figure 3 Scirrhous hepatocellular carcinoma. Bands of dense fibrosis separate cords and nests of tumoral cells(Hematoxyin and eosin stain, × 200).

CONCLUSION

Our understanding of the pathogenesis of HCC and diagnostic approach is evolving along with rapid advancement of diagnostic tools including molecular pathology.Updated pathologic classification of HCC is a reflection of the accrued knowledge and an effort to facilitate effective communication and collaborative studies. We hope that the effort further advances our understanding of the disease and ultimately improve patient care.

Figure 4 Combined hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarcinoma. Areas of conventional hepatocellular carcinoma (lower mid to right) are admixed with areas of discrete glands formation (upper left) (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 40).

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Precision surgical approach with lymph-node dissection in early gastric cancer

- Application of artificial intelligence in gastroenterology

- Clinical significance of programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 pathway in gastric neuroendocrine carcinomas

- Functional role of long non-coding RNA CASC19/miR-140-5p/CEMIP axis in colorectal cancer progression in vitro

- Seven-senescence-associated gene signature predicts overall survival for Asian patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

- Chronic functional constipation is strongly linked to vitamin D deficiency