Precision surgical approach with lymph-node dissection in early gastric cancer

2019-05-08ShinichiKinamiNaohikoNakamuraYasutoTomitaTakashiMiyataHidetoFujitaNobuhikoUedaTakeoKosaka

Shinichi Kinami, Naohiko Nakamura, Yasuto Tomita, Takashi Miyata, Hideto Fujita, Nobuhiko Ueda,Takeo Kosaka

Abstrac t The gravest prognostic factor in early gastric cancer is lymph-node metastasis,with an incidence of about 10% overall. About two-thirds of early gastric cancer patients can be diagnosed as node-negative prior to treatment based on clinicpathological data. Thus, the tumor can be resected by endoscopic submucosal dissection. In the remaining third, surgical resection is necessary because of the possibility of nodal metastasis. Nevertheless, almost all patients can be cured by gastrectomy with D1+ lymph-node dissection. Laparoscopic or robotic gastrectomy has become widespread in East Asia because perioperative and oncological safety are similar to open surgery. However, after D1+ gastrectomy,functional symptoms may still result. Physicians must strive to minimize postgastrectomy symptoms and optimize long-term quality of life after this operation.Depending on the location and size of the primary lesion, preservation of the pylorus or cardia should be considered. In addition, the extent of lymph-node dissection can be individualized, and significant gastric-volume preservation can be achieved if sentinel node biopsy is used to distinguish node-negative patients.Though the surgical treatment for early gastric cancer may be less radical than in the past, the operative method itself seems to be still in transition.

Key words: Stomach neoplasms surgery; Gastrectomy methods; Recovery of function;Sentinel lymph node surgery; Gastric cancer

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is a public health concern w orldw ide, and especially in Asia[1,2].Therefore, Japanese and South Korean physicians have focused on early detection of gastric cancer[3]. For decades, half of the gastric cancers d etected in Japan and Korea have been early-stage cancer[4]. The outcome of surgical resection for early gastric cancer is excellent, and most clinicians recognize that early gastric cancer is curable.The focus of recent topical d iscussion of early gastric cancer is minimally invasive treatment. Many early gastric cancers have been resected end oscop ically[5]. Less invasive approaches such as laparoscopic gastrectomy and robotic gastrectomy have also been w idely carried out[6-8]. On the other hand, standard surgery for early gastric cancer is distal partial gastrectomy (DG) or total gastrectomy (TG), with lymph-node dissection[9], so, even w ith a laparoscopic approach, post-gastrectomy symptoms and functional effects cannot be ignored[10]. In this article, we reconsider surgical treatment options for early gastric cancer and discuss the most appropriate treatment.

THE CHARACTERISTICS OF EARLY GASTRIC CANCER

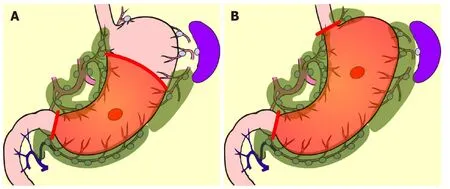

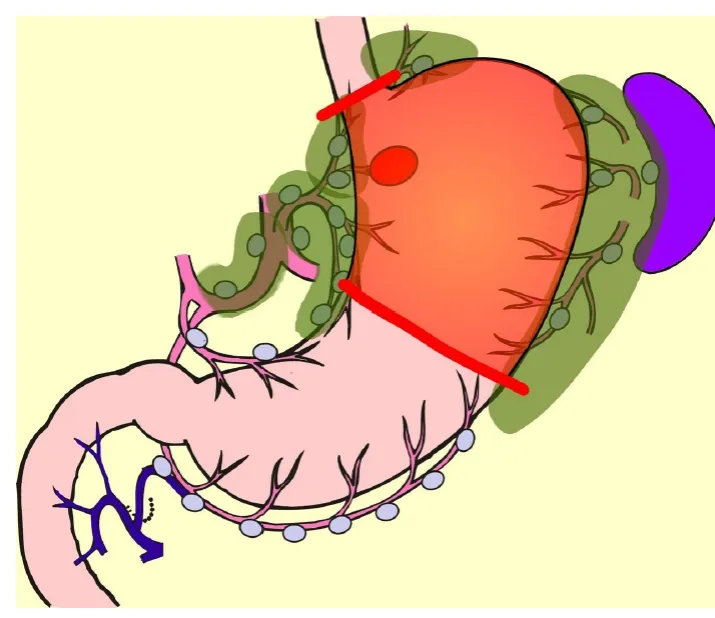

Early gastric cancer is defined as carcinoma in which depth of invasion is restricted to the mucosal layer or submucosa[11]. The presence or absence of lymph-node metastasis is irrelevant to the classification[11]. Most early gastric cancers are asymptomatic. Early gastric cancer is often detected with gastroscopy or barium meal during a healthscreening checkup[12]. Advanced gastric cancer is frequently associated w ith hematogenous or peritoneal metastases, while in contrast, early gastric cancer has few such distant metastases. On the other hand, early gastric cancer is rarely associated with lymph-node metastasis. The frequency of lymph-node metastasis is 2%-3% in mucosal cancer and 15%-20% in submucosal cancer[13-21]. Numerous previous studies have examined the location of these lymph node metastases. In the classification of gastric carcinoma of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association[22], the regional lymph nodes of the stomach are classified in detail and numbered. Currently, the extent of lymph-node metastasis has been evaluated in terms of the number of metastases, but in the past, regional nodes were grouped according to the location of the cancer, and the degree of lymph-node metastasis was evaluated based on which group of nodes the metastasis had reached. The precise data of nodal metastasis of early gastric cancer described in a representative literature are summarized in Table 1[23-26]. Most nodal metastasis in early gastric cancer was found to be limited to perigastric nodes and nodes number 7, 8a, and 9. Based on these results, the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association established D1+[27], the extent of lymph-node dissection for submucosal cancer (Figure 1). The disease-specific survival of D1+ gastrectomy for early gastric cancer is often given as 96%-98% in articles investigating the outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy[28-30].

In summary, the characteristics of early gastric cancer are as follows: there are few hematogenous and peritoneal metastases; the determining prognostic factor is lymph node metastasis; the incidence of nodal metastasis is about 10% overall; and even with nodal metastases, almost all patients can be cured by gastrectomy with D1+ lymphnode dissection.

ADVENT OF ENDOSCOPIC TREATMENT

Table 1 Summary of representative literature on the precise incidence of nodal metastasis in early gastric cancer

However, after D1+ gastrectomy, several functional symptoms are caused by the loss of the stomach. Red uction of gastric acid secretion impairs food digestive capacity.The amount of food intake decreases, nutritional status w orsens, and body w eight decreases. In addition, patients suffer from various postgastrectomy symptoms (PGS).They includ e reflux esop hagitis, d ump ing synd rome, d efecation abnormalities,anorexia, and abdominal pain. These symptoms are thought to compromise patients'quality of life (QOL). In add ition, several long-term aftereffects may occur, such as iron deficiency anemia, pernicious anemia, bone metabolic disorders, gastric stump cancer, cholelithiasis, and ileus[31-37]. Taking these disadvantages into consideration, if there is another therapeutic option, we would like to adopt it to avoid gastrectomy.

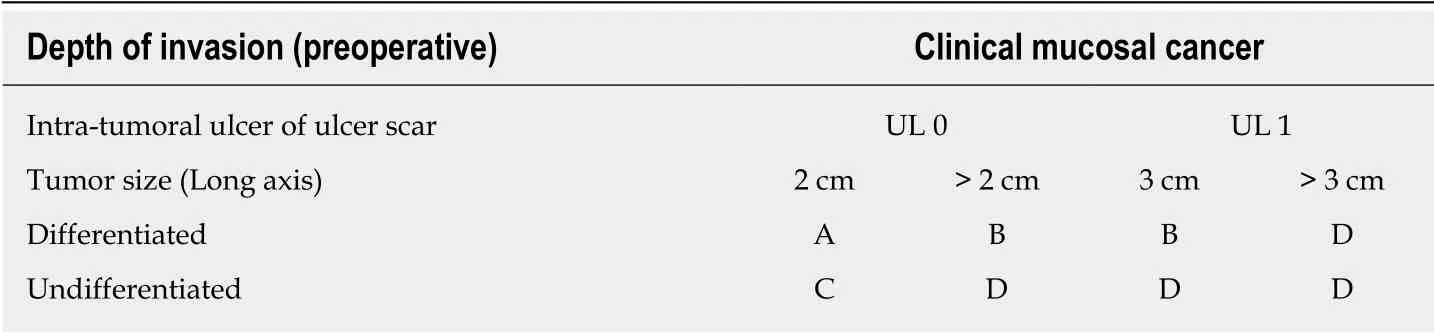

There are end oscop ic treatments. The end oscop ic treatments are alternatives to surgery using gastrofibroscopy. Gastroscopy was developed in Japan, and endoscopic treatments for gastric tumor w ere also invented and d evelop ed in Jap an. The beginning of endoscopic treatment is endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). EMR is a method of injecting p hysiological saline into the submucosal layer to lift the lesion,narrow ing the mucosa w ith a snare, and removing the mucosa by applying a high frequency current[38]. During the same period, end oscopic treatments using lesion cauterization w ith laser, heating p robe, argon p lasma d ischarge, etc., had been attemp ted. These therapies have some advantages and serious disadvantages, and they have not attained therapeutic value sufficient to replace surgical treatment[39,40].How ever, this situation has changed w ith the ad vent of end oscop ic submucosal d issection (ESD) technique[40]. ESD is the method of d issecting and removing the sp ecimen after incision of the mucosa around the entire circumference using a d ed icated d evice. In ESD, the specimen is removed in one p iece, w hich secures a safety margin, the treatment outcome is equal to prior surgical treatments, and it is possible for the patient to enjoy the same QOL as before the treatment. The greatest disadvantage of ESD w as its technical difficulty, though this difficulty was decreased by the development of electrocautery equipment and advancements in the dedicated device. Nowadays, ESD is not just an alternative to surgery, it is becoming a complete replacement for certain types of surgery[40]. The indication for ESD is a case in w hich the clinic-pathological data available prior to treatment is presumed to be negative for nodal metastasis. The frequency of nodal metastasis is 2%-3% in mucosal cancer and 15%-20% in submucosal cancer. Therefore, ESD is indicated in most mucosal cancers.Gotod a et al[41]proposed an indication for ESD from a stud y of surgical cases of tw o Japanese high-volume centers. Since the probability of nodal metastasis was set not to exceed the mortality rate after surgical resection, these criteria includes cases w ith a very low, but not zero, percentage probability of nodal metastasis. Recently, the longterm prognosis of the cases who underwent ESD according to this indication has been reported, and it has been confirmed that it is equal to the prognosis of the surgical resection[42-44]. Current indications for ESD are show n in Tables 2 and 3. These are new recommendations, stated in Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines for 2018[9]. In the table of indications (Table 2), Zone A is a former absolute indication. Zone B is new ly ad d ed absolute indication proven by p rospective observational trial JCOG 0607. Zone C is the exp and ed ind ication. Although this area is consid ered to be sufficiently curable, caution is necessary because the p roof of the p rosp ective observational trial JCOG1009/1010 has not been comp leted yet. Zone D is labeled“relative ind ication”. This zone comp rises an alternative treatment to surgery,reserved only for patients unable to end ure surgical treatment. The guid eline also d efines the evaluation of curability after resection (Table 3). If the sp ecimen is diagnosed as eCuraA or eCureB, the cancer is considered completely resected and no additional treatment is required. On the other hand, for eCuraC it is considered that the cancer has not been comp letely resected, and ad ditional treatment is necessary.The lesion of eCuraC-1 needs additional local treatment, and in the case of cCuraC-2 surgical treatment with lymph-node dissection should be added.

Figure 1 Standard surgery for early gastric cancer. A: Distal partial gastrectomy D1+; B: Total gastrectomy D1+.

LESS INVASIVE SURGICAL TREATMENT

In cases where ESD is not indicated, surgical resection is necessary because of the possibility of nodal metastasis[20,41]. In East Asia, most surgical treatment for early gastric cancer is laparoscopic D1+ gastrectomy. Laparoscopic gastrectomy w as introduced in Japan in 1991[45]. At the time, the quality of laparoscopic views was poor, and the instruments were inad equate to the task. Therefore, lymph-node dissection was extremely difficult. Laparoscopic surgeries for early gastric cancer at that time consisted of local resection (LR) without lymphadenectomy[46], and intragastric surgery d issecting the mucosa[47]. Though the pioneers also attempted laparoscopic DG, the extent of nodal dissection was confined to peri-gastric nodes[45].The indication for these treatments were cases in which lymph-node metastasis was presumed to be absent based on clinico-pathological features[45-47]. These approaches gradually d isappeared w ith the advent of ESD. Subsequently, the invention of ultrasonic activated d evices and technological advancements by surgeons have enabled laparoscopic lymph-node dissection comparable to conventional open surgery. Therefore, laparoscopic DG or TG with D1+ or D2 came to be performed as daily practice, and gradually replaced conventional open surgery.

There are many articles comparing laparoscopic gastrectomy and conventional open gastrectomy for patients with early gastric cancer[48,49], and a meta-analysis of prospective trials has also been conducted[49]. Perioperative surgical safety and oncological safety are considered similar[48,49]. The advantages of laparoscopic gastrectomy over conventional open surgery are as follows: the smaller size of the incision; lower number of times analgesic is required; lesser amount of intraoperative hemorrhage; and fewer occurrences of wound dehiscence and respiratory complications. On the other hand, the drawbacks are high cost and longer operation time[49].Although it is difficult to conclusively establish the minimal invasiveness of laparoscopic gastrectomy, it is suggested by the shorter time to first flatus and shorter hospital stays.

THE PGS AND QOL AFTER GASTRECTOMY

Because the size of the wound is clearly visible, laparoscopic surgery is an attractive option for hospitals. The high degree of difficulty of the laparoscopic gastrectomy is an attractive challenge for young surgeons. Thus, lap aroscop ic gastrectomy has become w idespread in East Asia. How ever, the benefits of laparoscopic gastrectomy in the long term have not yet been sufficiently examined.

Various PGS occur after gastrectomy[34-37], and, these symp toms seem to w orsen QOL[35]. The severity of these PGS and the d eterioration of QOL are subjective measures, and objective evaluations are difficult. These items are patient-reported outcomes w hose scientific valid ation must be performed using d efinitive questionnaires that have already been validated psychometrically. DAUGS[50]and PGSAS-45[34]have been reported as questionnaires specifically for post-gastrectomy patients.Of these, PGSAS-45 seems to be the de-facto standard to verify PGS and QOL, because it covers items that are consid ered important by gastrectomy specialists, it includes a short-form 8 (SF-8) for the assessment of generic QOL, and the standard values of Japanese patients are known based on data from more than 2500 cases[34].

Table 2 Updated preoperative indications for endoscopic submucosal dissection in Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018

Kinami et al[51]evaluated the superiority in PGS and QOL at least 1 year after surgery of patients w ho underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy, using data from the PGSAS study for ad ditional analysis. The outcome measures included in the PGSAS-45 are classified into three d omains: the symptom d omain, the living status domain,and the QOL d omain[34]. A few main outcome measures of PGSAS-45 w ere superior after lap aroscopic, comp ared to conventional op en, DG surgery. These measures w ere: The need of ad ditional food; d issatisfaction w ith symptoms; and the mental component summary of SF-8. These items were of the living status or QOL domain,not the symptom domain. In contrast, for TG, there w as no difference in the scores of main outcome measures betw een lap aroscop ic surgery and conventional op en surgery. From this large-scale analysis, it was concluded that there is no advantage for lap aroscop ic TG from the view point of the PGS[51]. Generally, the only difference betw een laparoscop ic surgery and conventional open surgery is the length of the incision. Therefore, a large difference in PGS betw een laparoscopic and open surgery would not be expected.

LIMITED SURGERY FOR EARLY GASTRIC CANCER

Even if the advantages are small, such as the size of the incision, the number of times analgesic is used, and a slight improvement in QOL, it is reasonable to apply laparoscopic gastrectomy to the early gastric cancer, if the surgical and oncological safety are equivalent. However, if other approaches can be used to prevent PGS,palliation of PGS should be prioritized to benefit patients in the long term, rather than focusing on the small incision size afforded by laparoscopic surgery. Limited surgery is a method expected to palliate PGS. Limited surgical approaches consist of reduced resection area of the stomach and smaller extent of nodal dissection. These include pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG), proximal gastrectomy (PG), and LR. In performing LR, the unconventional decision to omit lymph-nod e dissection is necessary. Therefore, LR is rarely done today, while ESD is routinely performed[52].

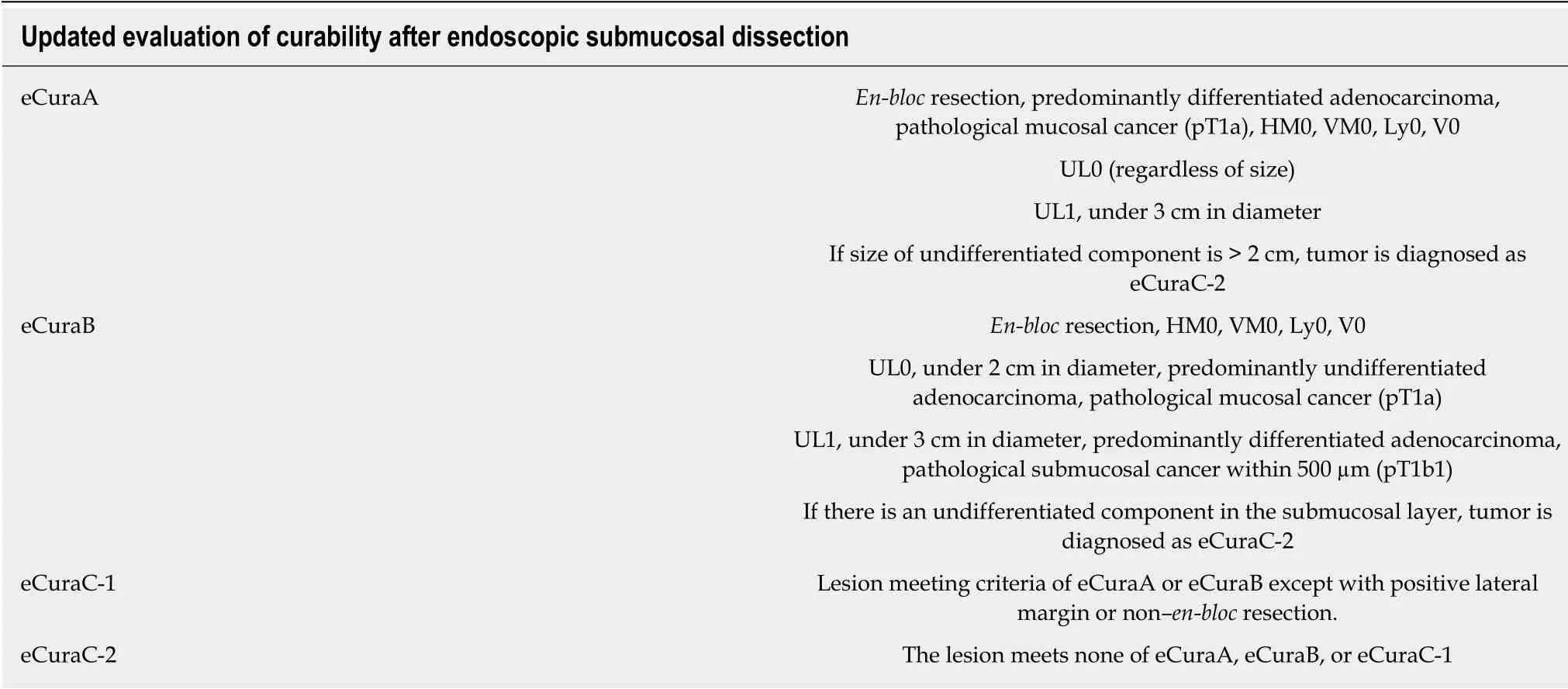

In comparison with DG, PPG is a pylorus-preserving procedure[53]. Generally, the right gastric artery and pyloric branch of the vagus nerve are preserved to secure an antral cuff of about 3 cm. It is expected to be effective for preventing dumping symptoms, regurgitation of duodenal juice into the stomach, and gallstone formation after gastrectomy[54,55]. This procedure is indicated in cases in which right gastricartery lymph-node dissection can be omitted. Practically speaking, these patients will have tumors located at the middle part of the stomach with distal margins more than 4 cm from the pylorus[9]. Even if PPG is adopted, lymph-node dissection at nodes other than those located at the right gastric artery area is possible, and D1+ for PPG is included in the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines[9](Figure 2). The survival outcome of PPG is considered equal to that of DG[54,55]. In the PGSAS study, it was confirmed that, in comparison with Billroth I cases, diarrhea and dumping symptoms and the necessity of additional food was lower in PPG cases[56].

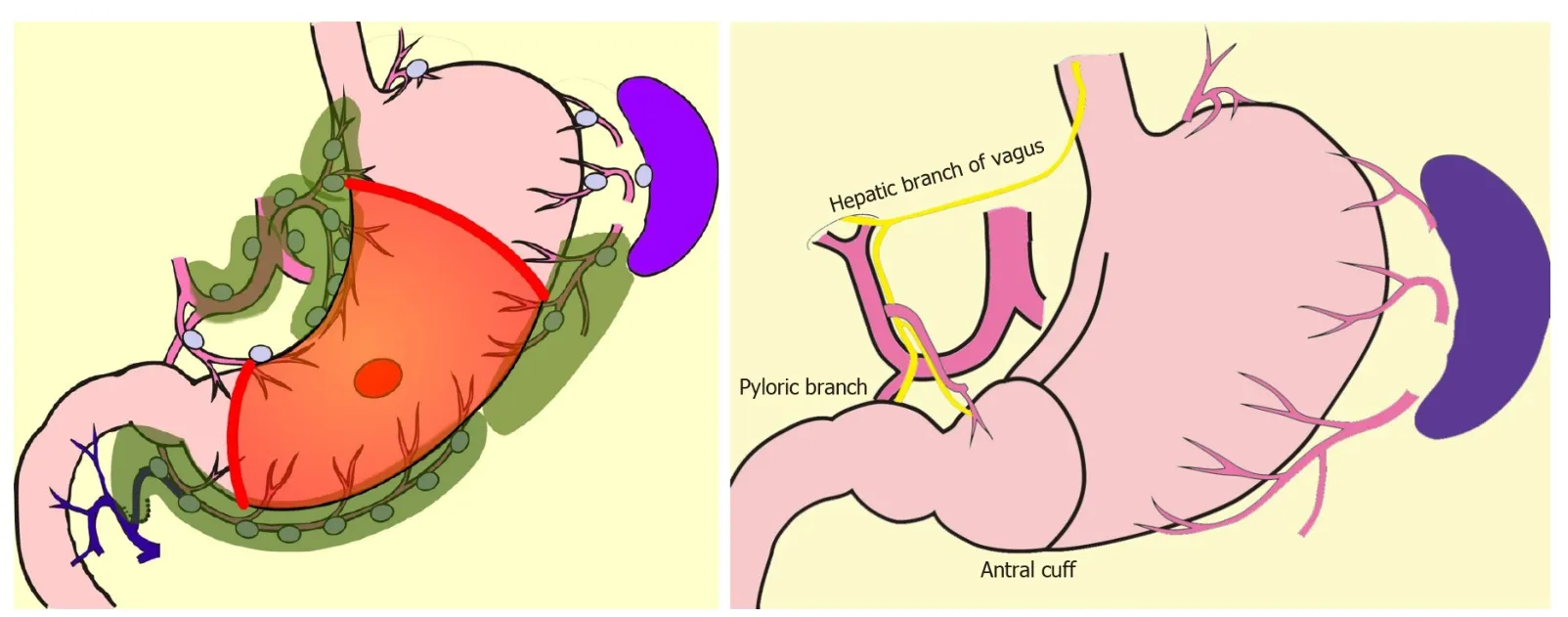

PG is an alternative to TG for early gastric cancer located in the stomach's upper third. Compared with TG, PG preserves over one-half of the distal stomach and is considered to be superior in improving nutritional status and preventing anemia because of higher dietary intake and preserved secretion of gastric acid, Castleintrinsic factor, and gastrin. It is reported that if the cancer lesion is limited to the upper-third of the stomach, dissection of the lymph nodes along the right gastric artery and right gastroep ip loic artery can be omitted w ithout compromising radicality[57-60]. In the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guideline, D1+ for PG is set[9](Figure 3). In the PGSAS study, PG prevented diarrhea and dumping symptoms,slightly diminished weight loss, and lowered the necessity of additional food than TG[36].

Table 3 Updated evaluation of curability after endoscopic submucosal dissection in Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018

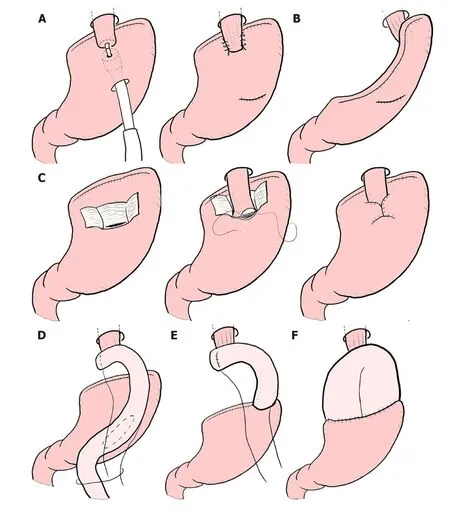

Though these limited surgeries are superior in terms of preserving some functions lost by gastrectomy, it is known that some patient dissatisfaction may result from PGS. PPG occasionally creates cases where the hospitalization period is extended due to either delayed gastric emptying or small-stomach symptoms[61]. There are also many cases in which reflux esophagitis or gastric stasis are generated after PG[62,63].Due to these facts, such limited surgeries are sometimes considered d ifficult procedures. In a questionnaire survey conducted by gastric cancer specialists in Japan by the Japanese Society for Gastro-surgical Pathophysiology, only 30% of surgeons had adopted PPG and 70% of surgeons had adopted PG. Several attempts to reduce the aforementioned p ostop erative d ifficulties have been reported. In PPG,preservation of the infra-pyloric arteries and veins has been reported to be beneficial in preventing delayed gastric emptying[64-66]. The PGSAS study also concluded that size of proximal remnant stomach, gastro-gastric anastomoses with hand sewing, and adequate size of the antral cuff were helpful in reducing postoperative disability[67]. In PG, the reconstruction method is considered to be useful for the prevention of reflux esophagitis, and pyloroplasty and preservation of the hepatic and pyloric branches of vagus are considered to be useful for the reduction of gastric stasis. Reconstruction is particularly important, and various method to prevent reflux have been devised(Figure 4), but every method has its own advantages and disadvantages, and there is still no definitive operative method[68-76]. Methods to reduce postoperative damage of PG were also studied in the PGSAS study, and it has been concluded that a large distal remnant stomach and a pyloric bougie were effective[77].

Though PPG and PG are complicated procedures, reports of laparoscopic PPG and laparoscopic PG have increased recently[78-82]. However, the results of PPG and PG performed laparoscopically are equivalent to conventional open surgery in terms of safety and radicality, while preservation of function is not yet fully proven. Regarding function preservation, a retrospective stud y comparing laparoscopic PPG with laparoscopic DG was reported, again with fewer cases presenting with diarrhea and dumping symptoms[80]. However, reports comparing PPG or PG in conventional open surgery and laparoscopic surgery are not impressive[82]. Kinami et al[51]analyzed the data of the PGSAS study and found that laparoscopic PPG had better physicalcomponent scores on SF-8 than open PPG, whereas there was no difference in the scores for main outcome measures between laparoscopic PG and open PG. From these results, it is concluded that the function preserved in PPG and PG in laparoscopic surgeries are equivalent to those in the conventional open surgeries. Thus, it appears that there is little long-term advantage in laparoscopic surgery.

Figure 2 Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy D1+.

FUNCTION PRESERVING RADICAL GASTRECTOMY

As described above, studies of large cohorts using the PGSAS demonstrated that PPG and PG are superior in the occurrence rate of dumping symptoms and diarrhea, and the maintenance of eating habits. Nevertheless, comparing PPG and DG, or PG and TG, other functional outcomes were found to be similar[36,56]. Therefore, more extensive gastric preservation is required to prevent more PGS outbreaks and improve QOL.The extent of resection of the stomach is insep arable from that of lymp h-nod e dissection. Therefore, in order to carry out better function-preserving procedures, it is necessary to bold ly omit the lymp h-nod e d issection in ord er to p reserve blood circulation to the stomach.

What is the lymph-nod e metastasis rate of surgical cases for early gastric cancer today, w hen ESD has become standard? In the latest version of the Japanese gastriccancer treatment guid eline (5thed ition, in Jap anese), the results of research on equalization and actual conditions of gastric-cancer medical treatment in Japan as of fiscal 2013 is reported[9]. This study investigated the course of gastric-cancer treatment in 297 cancer hospitals in Japan. The total number of patients with gastric cancer was 44879, and the endoscopic treatment rate for pretreatment T1N 0 gastric cancer w as 64.1%. Therefore, at stand ard cancer treatment facilities in Jap an, the number of primary surgical cases for T1N0 gastric cancer may be estimated to be approximately one-third. This is consid ering that 90% of early gastric cancers are negative for metastases. If all endoscopically treated cases are assumed to be node negative, 70% of surgical cases are calculated to be negative for metastasis. Therefore, only 30% of cases require D1+ (i.e., are those in w hich the possibility of lymph-nod e metastasis cannot be ruled out). D1+ may be unnecessary in 70% of cases.

Currently, how ever, it is difficult to reduce the extent of dissection below D1+. The frequency of metastasis in group 2 lymph nodes is low. There are two opinions: one is that there is no large benefit from the prophylactic dissection[16]; and the other is that there is a significant difference in the prognosis for D1 and D2[17]. The general view of specialists is that the extent of lymph-node dissection should not be indiscriminately reduced. In addition, there is no large d ifference in gastrectomy extent betw een D1+and D1. Reduction of nodal d issection from D1+ to D1 is of little value in terms of PGS prevention. To prevent PGS, intraoperative d iagnosis of node-negative patients should be required to establish the ap propriateness of omitting p eri-gastric nodal dissection, with its benefits of preservation of gastric blood flow and reduction in the resection area of stomach.

SENTINEL NODE BIOPSY AND BASIN DISSECTION

Figure 3 Proximal gastrectomy D1+.

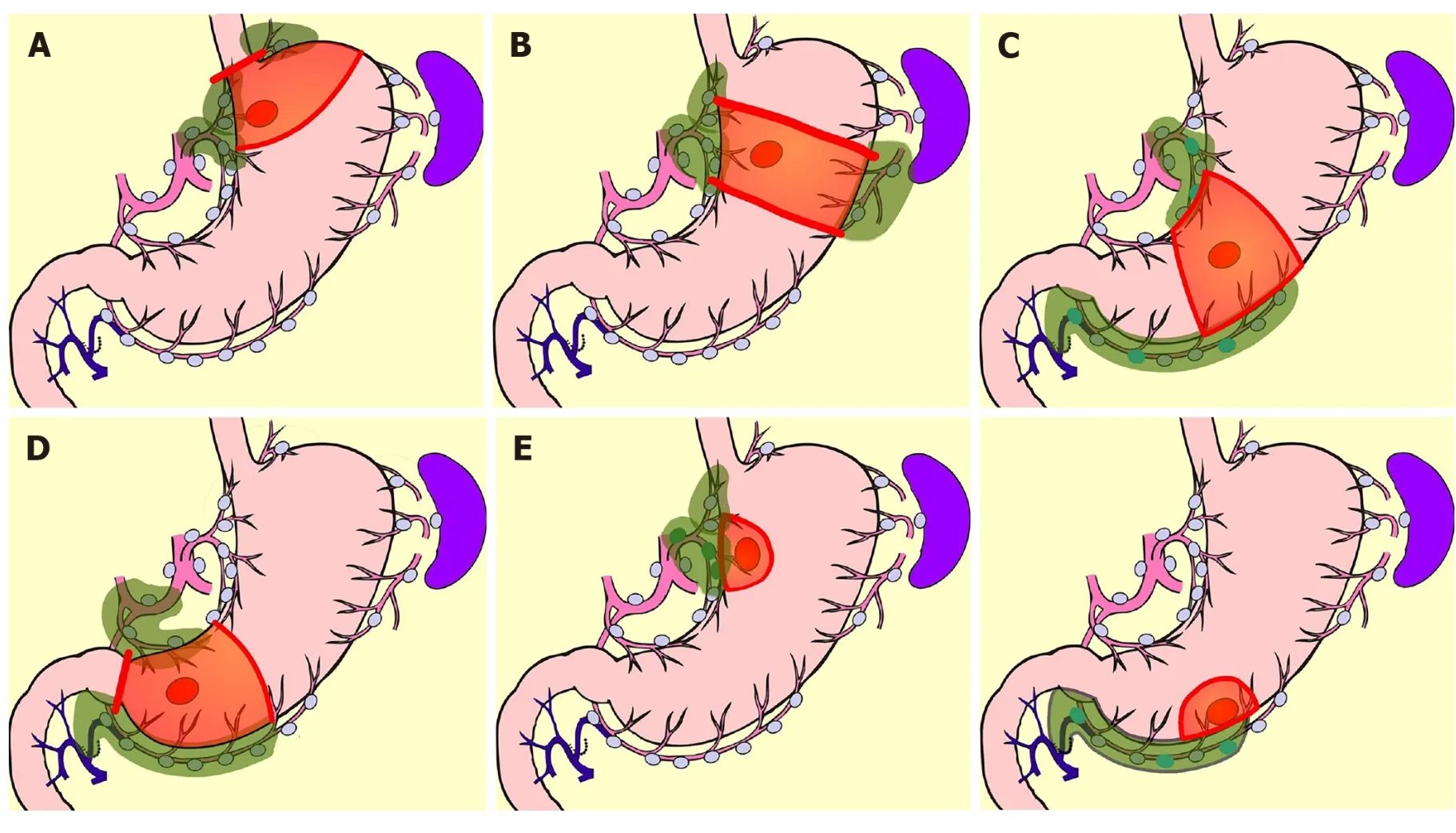

Currently, the best reliable method of intraoperative nodal diagnosis is the sentinelnod e biopsy[83]. A sentinel node (SN) is defined as the nod e that receives lymphatic flow directly from a primary tumor. SN biopsy has been attempted most for gastric cancer among all gastrointestinal cancers[84-88]. In a multicenter prospective clinical trial in Japan, the SN concept was proved valid in early gastric cancer[85]. It is believed that the extent of lymp h-nod e d issection can be red uced w ithout comp romising the rad icality, if the nod e-negative p atient is able to be d iagnosed by SN biopsy[89].Unfortunately, unlike breast cancer, in gastric cancer there is no room for add itional nodal dissection after initial surgery, the prognosis of micro-metastasis is unknow n,and a method for p red icting non-SN metastases in p atients w ith p ositive SN metastases has not been established. Rapid intraoperative d iagnostic method s for nod al metastasis w hich can d iagnose to the micro-metastasis level has not been established either. Therefore, it is considered premature to omit all lymphadenectomy by utilizing SN biop sy in gastric cancer. Lymp hatic-basin d issection has been proposed as a realistic solution for omitting the nodal dissection[84-89]. This is a method for gastric SN biop sy, in w hich the lymphatic basin id entified by d ye mapp ing is removed en-bloc, and the SNs are identified ex-vivo after basin d issection, and is sent for intraoperative rapid diagnosis[88]. After SN biopsy, D2 gastrectomy is added if the patient is diagnosed as node-positive, but if the patient is diagnosed as node negative,ad d itional d issection is omitted, the gastric feed ing artery outsid e the basin is preserved, and the resection area of stomach is minimized. Thus, by adopting the SN biopsy, a large-area stomach-sp aring function-p reserving radical gastrectomy, as show n in Figure 5, can be performed. Kinami et al[88]reported that there w as no recurrence in 174 cases in w hich nodal d issection outsid e the basin w as omitted.Isozaki et al[90]reported that PGS in cases involving function-preserving procedures according to this protocol were clearly better than standard procedures.

A large-scale prospective stud y is currently ongoing in Korea to verify survival prognoses after gastric-cancer SN biopsy[91]. Additionally, a prospective trial to verify both prognosis and function-preservation effects of the function-preserving radical gastrectomy accompanied by basin d issection is on-going in Jap an[89]. In add ition,attemp ts to rep rod uce this function-p reserv ing rad ical gastrectomy using laparoscopic surgery have also been reported[84,89,92]. If the tw o prosp ective stud ies described above show evidence supporting SN biopsy in gastric cancer, the surgery for early gastric cancer w ill eventually shift from the current lap aroscop ic D1+gastrectomy to a laparoscopic, tailor-mad e, function-preserving radical gastrectomy,in which patients may be diagnosed as node-negative intraoperatively.

How ever, there are many p roblems to be solved in SN-d irected, tailor-mad e function-p reserving gastrectomy techniques. Solutions for the follow ing issues are necessary: setting the prop er range for lymphatic basin dissection; establishment of quick, convenient, universally-ap plicable intraoperative d iagnosis method; and strategies for p reventing d ysfunction after surgery. Physicians should also p ay attention to the risk of metachronous multiple gastric cancers w hen the remnant stomach area is large.

SUMMARY: OPTIMAL SURGICAL TREATMENT, NOW AND IN THE FUTURE

Early gastric cancer can be cured by surgical treatment, and physicians must be mindful of reduction of PGS and improvement of QOL over the long term after the operation. The authors intention in this article is to provide a roadmap for developing precision surgery for early gastric cancer from these three perspectives: Lymph-node dissection, function preservation, and a less invasive approach.

Lymp h-nod e d issection: D1+ is an ap p rop riate and stand ard ized extent of dissection for early gastric cancer in view of radicality and safety. How ever, D1+ is not essential in all cases. The extent of lymph-node dissection can be individualized if SN biopsy is used to distinguish node-negative patients.

Figure 4 Reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy. A: Additional anti-reflux procedures for esophagogastric anastomosis; B: Gastric tube reconstruction; C:Double-flap technique (Kamikawa method); D: Double tract reconstruction; E: Jejunal interposition; F: Jejunal pouch interposition.

Function preserving: Depend ing on the location and size of the p rimary lesion,preservation of the pylorus or cardia should be considered. If the patient is diagnosed as node-negative by SN biopsy, significant, large-volume gastric preservation can be achieved.

Less invasive approach: There seems to be no problem with the use of laparoscopic surgery because the perioperative and oncological safety are similar to open surgery,but the physician should be aware that laparoscopic surgery is technically difficult.Prioritizing completion of laparoscopic surgery and forgoing conversion to limited or function-preserving open surgery is undesirable in terms of PGS reduction. However,if advances in surgical devices or technological innovations in robotic-assisted surgery are made, all operations will eventually be undertaken using a less invasive approach.

Though the surgical treatment for early gastric cancer is currently radical, the operative method itself seems to be still in a transitional stage. Evidence-based gastriccancer SN biopsy and technological innovations in robotic-assisted surgery are sure to bring a new era of minimally invasive, significantly function-preserving surgery.

Figure 5 Function-preserving radical gastrectomy derived by sentinel node biopsy. A: Mini-proximal gastrectomy; B: High segmental gastrectomy; C:Segmental gastrectomy; D: Mini-distal gastrectomy; E: Local resection of stomach.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Update on hepatocellular carcinoma: Pathologists' review

- Application of artificial intelligence in gastroenterology

- Clinical significance of programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 pathway in gastric neuroendocrine carcinomas

- Functional role of long non-coding RNA CASC19/miR-140-5p/CEMIP axis in colorectal cancer progression in vitro

- Seven-senescence-associated gene signature predicts overall survival for Asian patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

- Chronic functional constipation is strongly linked to vitamin D deficiency