Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of the biliary system:Techniques, indications and future perspectives

2019-02-27PieterHindryckxHelenaDegrooteDavidTatePierreDeprez

Pieter Hindryckx, Helena Degroote, David J Tate, Pierre H Deprez

Abstract Over the last decade, endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD)has evolved into a widely accepted alternative to the percutaneous approach in cases of biliary obstruction with failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP). The available evidence suggests that, in experienced hands, EUS-BD might even replace ERCP as the first-line procedure in specific situations such as malignant distal bile duct obstruction. The aim of this review is to summarize the available data on EUS-BD and propose an evidence-based algorithm clarifies the role of the different EUS-BD techniques in the management of benign and malignant biliary obstructive disease.

Key words: Endoscopic ultrasound; Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography;Biliary drainage; Rendez-vous; Hepaticogastrostomy; Choledochoduodenostomy

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic biliary drainage, achieved by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP), has been the established first-line therapy for both benign and malignant biliary obstruction since the beginning of the 1990s.However, even in experienced hands, ERCP fails in 5%-10% of cases[1]because of impossible cannulation or inaccessibility of the major papilla (for example due to tumoral invasion of the ampullary region or surgically altered anatomy). Moreover,ERCP can be complicated by pancreatitis, cholangitis, bleeding, perforation or stent dysfunction requiring reintervention[1,2]. Until recently, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) was the only non-surgical alternative to achieve biliary drainage in cases of failed ERCP. However, reported adverse rates of PTBD are high with 1 out of 4 patients suffering from bleeding, bile leak or acute cholangitis after the procedure[3].

Endosonographic-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) techniques have recently been introduced as an alternative to PTBD. Over the last decade, increasing operator experience reduced the number of adverse events and augmented technical and clinical success rates of EUS-guided biliary drainage. Many retrospective comparative analyses have concluded that EUS-BD is associated with fewer adverse events as compared to PTBD and should be the treatment of choice in cases of failed ERCP[4].

EUS-BD might even be considered a first-line approach in patients with distal malignant bile duct obstruction. Three randomized controlled trials that compared EUS-BD with ERCP have been published within the last year suggesting that the success-rate of both techniques is similar, but adverse events and reintervention rates might be lower for EUS-BD[5-7]. In other words, the “ERCP-first” paradigm is not sacrosanct, at least for specific indications.

In this review, we describe the different EUS techniques for biliary drainage.Contemporary evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of EUS-BD in benign as well as malignant biliary obstructive diseases is discussed. We highlight the comparison between EUS-BD, PTBD and ERCP. Finally, we provide a practical flowchart that positions EUS-BD in the current therapeutic algorithm of biliary obstruction and conclude with some future perspectives.

SEARCH STRATEGY

We searched for relevant publications using PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library, from their inception until Dec 1, 2018. Our search algorithm included the following terms: Endoscopic ultrasound, biliary drainage, ERCP, bile duct,percutaneous, rendez-vous, hepaticogastrostomy, choledochobulbostomy,choledochoduodenostomy, hepatico-enterostomy, choledocho-enterostomy in various combinations. We critically reviewed articles published in English and gave priority to randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses.

TECHNIQUES

General technique

EUS-guided biliary drainage involves the visualization of dilated extra- and or intrahepatic bile ducts and the puncture of these ducts with a needle or a direct access device (LAMS). Puncture of dilated left intrahepatic bile ducts is usually performed from the upper part of the stomach whereas the common bile duct is best accessed from the bulbar portion of the duodenum. Aspiration of bile confirms the position within the bile duct. If necessary contrast injection provides cholangiography to plan the desired intervention. Subsequently, several procedures can be performed,depending on the clinical scenario and the puncture site.

Rendez-vous technique:This technique is mainly used for benign indications when retrograde cannulation of the bile duct fails. A prerequisite for the technique is an endoscopically accessible ampulla or anastomosis. After puncture of the bile duct, a guidewire is advanced via the needle through the ampullary orifice into the duodenum or the surgical anastomosis. While this might be easy in some cases,several challenges may occur. Firstly, with the trans-bulbar approach, the wire may find its way into the intrahepatic bile ducts rather than the ampulla. This can usually be overcome by moving to a long scope position, by deflecting the endoscope tip towards the ampulla or by using a guidewire with an angled tip. Secondly, the wire may not be able to pass the ampullary orifice (due to a distal stricture, impacted stone,ampullary stenosis, etc.). In that case, it might be necessary to insert a papillotome over the wire into the bile duct to further steer and support the wire. Advancement of a papillotome requires a prior cystogastrotomy using a 6 Fr cystogastrotome(preferred) or 4 mm balloon dilatation. Once transpapillary passage of the wire is achieved, the wire should be introduced deeply in the duodenum. The needle and the endoscope are removed leaving the wire in place. Next, a duodenoscope is introduced to visualize the wire protruding from the ampullary orifice. In most cases it is possible to cannulate the bile duct next to the wire. Occasionally, the wire needs to be retrieved using a snare into the endoscope instrument channel. In this way a papillotome can be introduced over the wire directly in the bile duct.

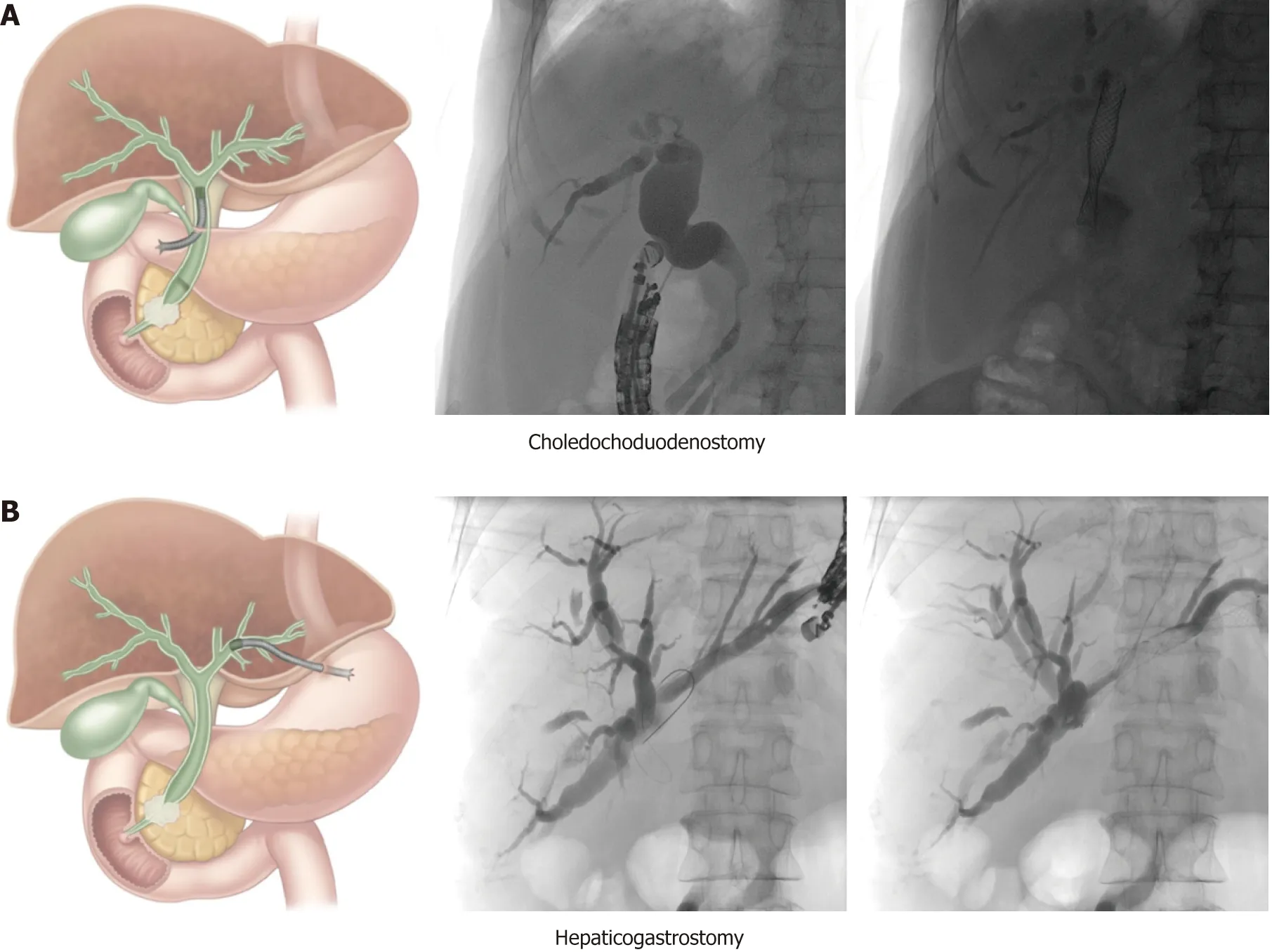

Choledochoduodenostomy (CDS):This technique (Figure 1A) is mainly used for malignant distal bile duct obstruction when the ampulla is not accessible or when retrograde cannulation fails. It is important to verify duodenal patency beforehand, or to place a duodenal stent or an endoscopic gastrojejunostomy if indicated. The conventional technique involves trans-bulbar puncture of the dilated common bile duct, then a guidewire is advanced upstream into an intrahepatic bile duct and the puncture tract is dilated with a cystogastrotome (6 Fr) or a dilation balloon (4 mm).Thereafter, a fully covered metallic stent can be left in place to achieve biliary drainage. Stent migration can be an issue and can be overcome in different ways: By using a long covered metal stent, a LAMS (AxiosR, Boston Scientific, USA; NagiRstent,Taewoong Medical, South Korea) or by placing a partially covered stent with the uncovered portion within the bile duct. However, no short partially covered biliary stents are available at the current time (minimal length is currently 8cm with an uncovered part of 3 cm or 4 cm).

The novel approach involves the use of a LAMS, with direct puncture of the dilated common bile duct using pure cut current, optional placement of a guidewire and delivery of the LAMS without a further dilation step. This technique is now favored in most centers. An 8 mm or 10 mm diameter stent is usually used, and for safe LAMS placement the diameter of the CBD should exceed 10 mm, to avoid misplacement

Hepaticogastrostomy (HGS):This technique (Figure 1B) can be used for proximal(perihilar) bile duct obstruction when the ampulla is not accessible, when retrograde cannulation fails, or when the left lobe cannot be drained by ERCP. It can also be used for malignant distal bile duct obstruction if the common bile duct is not accessible due to surgically altered anatomy (e.g., after Whipple procedure or roux-en-Y gastric bypass). It is the preferred technique by some experts in any distal malignant obstruction. In cases of perihilar bile duct obstruction, this route of drainage can only drain the left hepatic ducts in case of total hilar obstruction, or both liver lobes in case of left-right biliary communication. After puncture, guidewire introduction and dilatation of the puncture tract (using a 6 Fr cystogastrotome or a 4 mm dilatation balloon), a partially covered stent can be placed, with the uncovered part in the bile duct to prevent migration and the covered part bridging the bile duct and the gastric lumen (Giobor stent, Taewoong Medical, South Korea).

In benign diseases, the HGS can be created with a plastic stent to allow for removal,dilation and sequential repeat access to the bile ducts either for stricture dilatation, or stone lithotripsy.

EUS-guided antegrade transpapillary stent placement:This technique involves the same initial steps as described above for the rendez-vous technique but after placement of the guidewire, a metallic stent is advanced through the ampullary orifice in an antegrade fashion. This is technically more challenging than EUS-guided transmural drainage and does not eliminate the risk of pancreatitis. As such, the technique should be reserved for patients with benign distal bile duct strictures (e.g.,in the context of chronic pancreatitis) in whom both the retrograde and rendez-vous approaches have failed. HGS and antegrade stent placement may be combined.

Figure 1 Schematic and case illustration of the choledochoduodenostomy (A) and the hepaticogastrostomy(B). Patient A had a distal bile duct obstruction due to a locally advanced pancreatic head carcinoma. Patient B had a large perihilar metastasis of a small cell lung carcinoma with a complete obstruction of the proximal common bile duct but preserved left-right intrahepatic bile duct communication. The choledochoduodenostomy can be combined with a duodenal stent or an endoscopic gastrojejunostomy if indicated. Adapted from Paik et al[5].

INDICATIONS

Malignant biliary obstructive disease

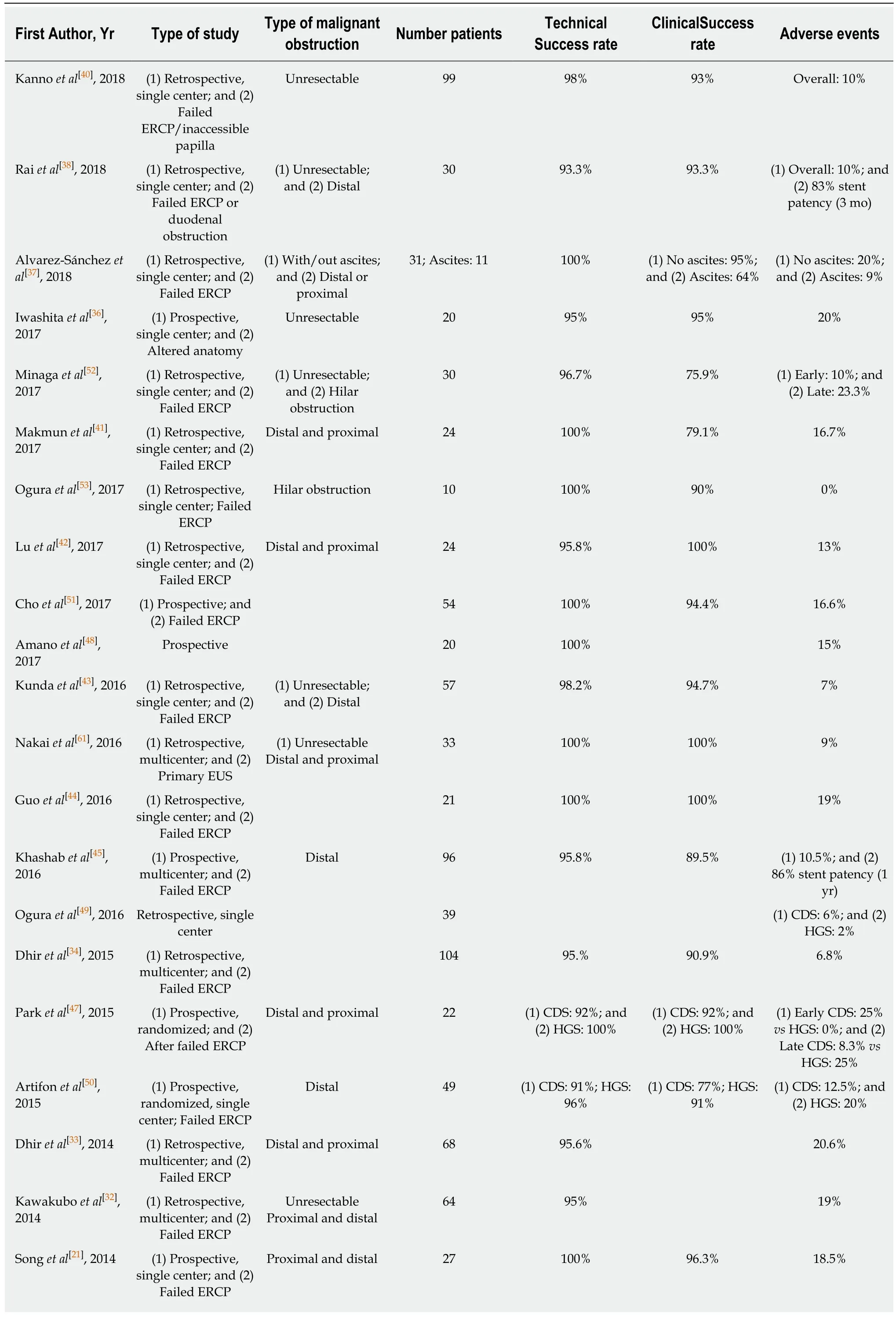

In 2001, Giovannini et al[8]first reported a successful EUS-guided CDS procedure in a patient with pancreatic carcinoma and distal malignant biliary obstruction after failed ERCP. Two years later Burmester et al[9]published a one-step method without the need for switching from the ERCP to the EUS scope. This was followed by the publication of several small case series and studies demonstrating technical and clinical feasibility of EUS-guided BD for malignant indications after ERCP failure with an acceptable safety profile[10-21]. Due to the small size of the individual studies, the overall efficacy and adverse event profile of EUS-BD had not yet been established. A meta-analysis of Moole et al[22]pooled 16 studies (until January 2016, n =528)[13,15,18-20,23-30]and reported a 90.9% success rate for rescue EUS-guided BD with an overall procedure related adverse event rate of 16.5%. Khan et al[31]showed very similar results in their meta-analysis that pooled 20 studies (until 2015, n = 1186, 6 studies overlap with Moole et al[22])[21,32-35]. The technical success and post-procedure adverse event rate were 90% and 17%, respectively. Both meta-analyses included studies that evaluated EUS-BD both in benign and malignant indications. In Table 1 all published case series or studies investigating exclusively malignant biliary obstruction are listed (case reports with less than 10 cases are not considered). From this table it is evident that inclusion criteria were not homogenous, different techniques and materials were used and the definition of technical and clinical success was diverse. Some studies examined subpopulations such as patients with altered biliary anatomy[36]or ascites[37]. More recent publications have larger patient cohorts,but the majority are retrospective and single center[29,37-44]. Khashab et al[45]published a larger (n = 96), prospective, multicenter study and demonstrated excellent efficacy and safety of EUS-BD for malignant distal biliary obstruction. It is generally advised that the procedure should be performed by experts in biliopancreatic endoscopy and advanced endoscopic ultrasound.

CDS vs HGS:The meta-analysis by Uemura et al[46]in 2018 (10 studies until April 2017, n = 434 patients)[21,32,35,44,45,47-51]did not demonstrate superiority in terms of technical success (CDS: 94.1% vs HGS: 93.7%) and clinical success (CDS: 88.5% vs HGS: 84.5%) comparing EUS-CDS and EUS-HGS in patients with malignant biliary obstruction (only 2 studies included distal obstruction). They also found both procedures to be equivalent in terms of safety. This is contrary to previously published studies that concluded EUS-HGS was associated with more adverseevents[31,33]. The authors proposed that the choice of approach may be selected based on patient anatomy and the presence of bile duct dilatation. For example, EUS-CDS is not suitable for proximal (hilar) biliary obstruction, where an intrahepatic EUS-BD approach is required. In the specific situation of hilar malignancy EUS-guided HGS was found to be safe and effective[52,53], although the duration of efficacy was limited[40]and lower clinical success rates were demonstrated than for distal obstruction[41].

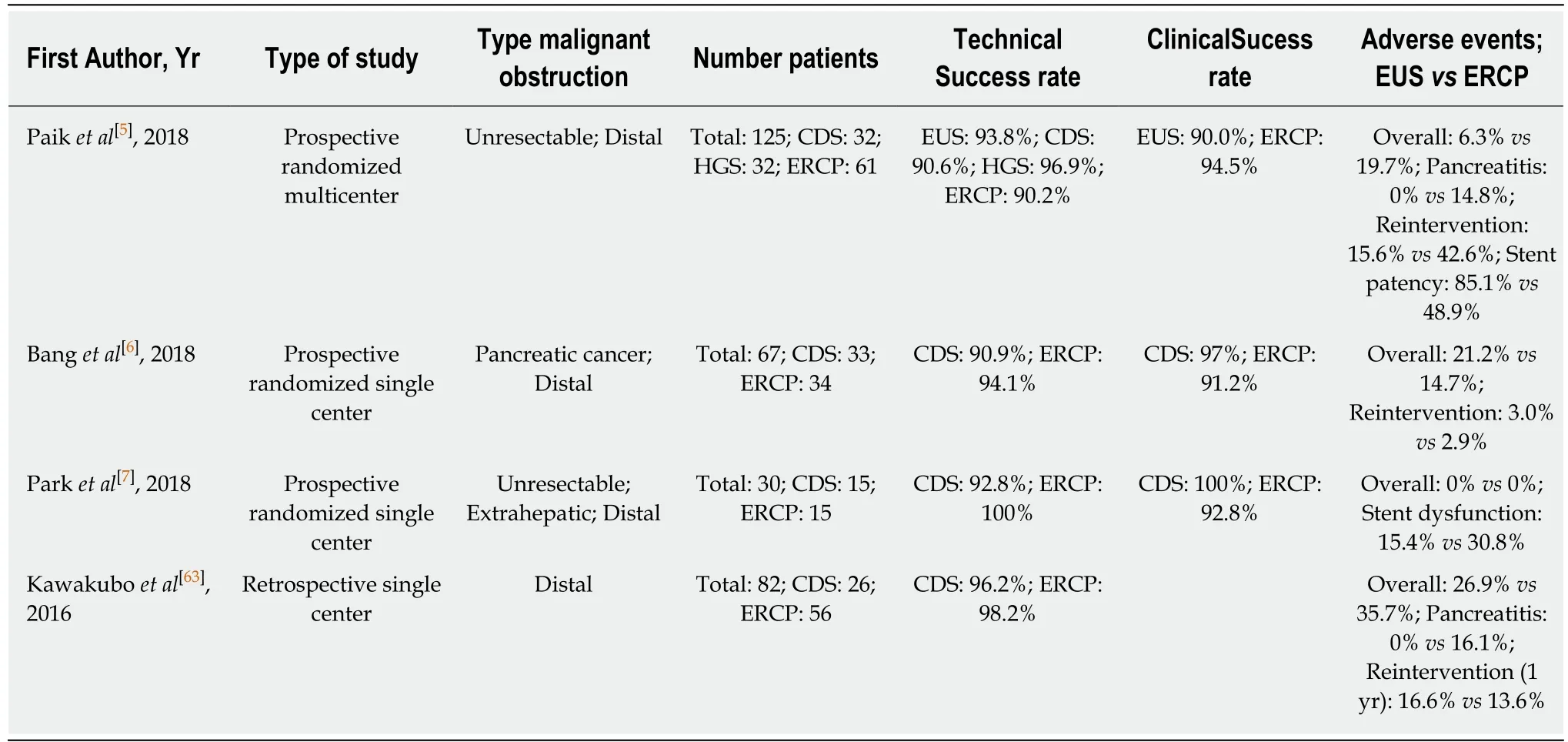

Table 1 Outcome of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage

EH: Extrahepatic; IH: Intrahepatic; AG: Antegrade; CDS: Choledochoduodenostomy; HGS: Hepaticogastrostomy; RV: Rendezvous; GG: Gastrogallbladder; HES: Hepaticoesophageostomy; SEMS: Self-expandable metal.

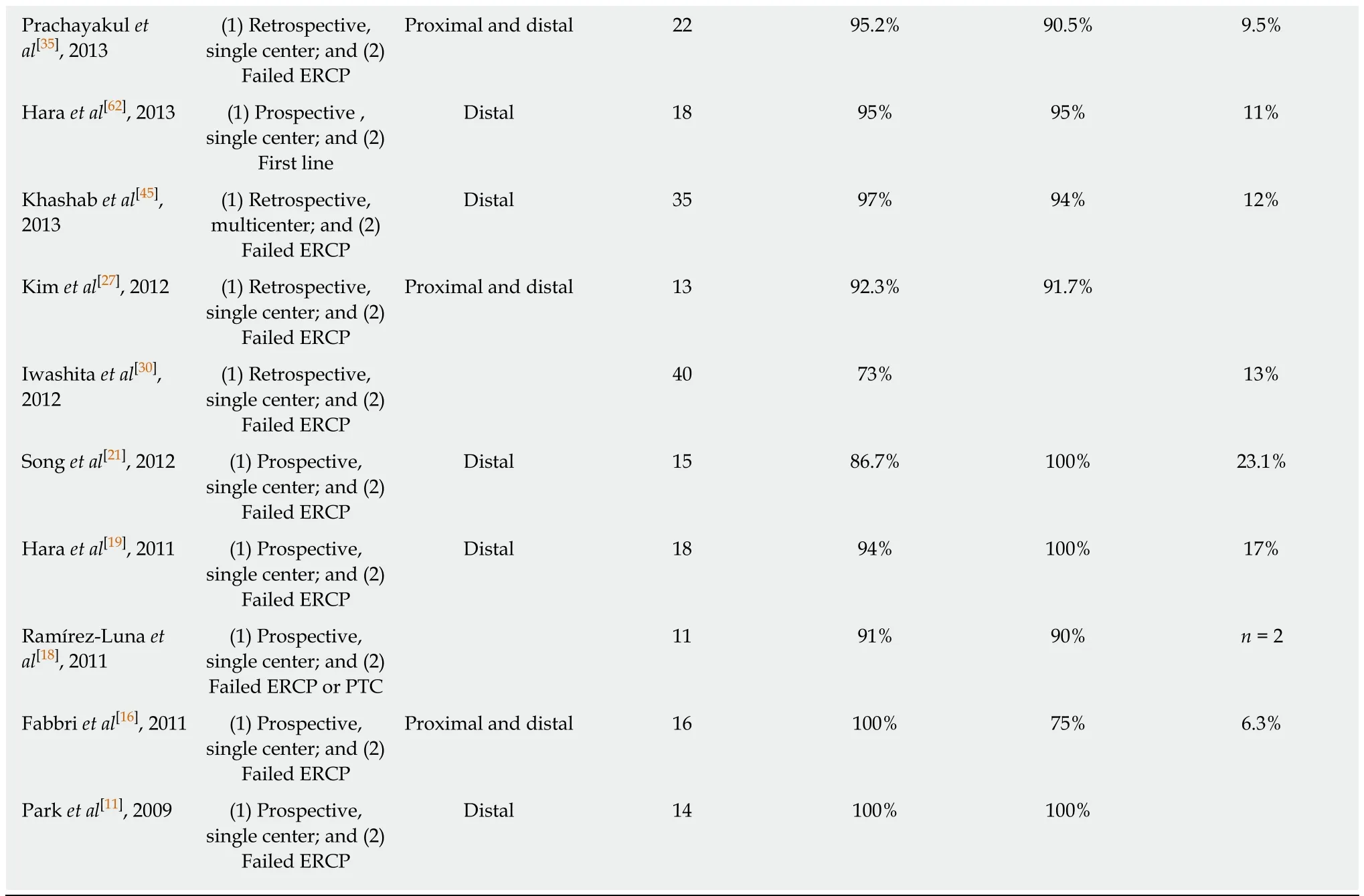

EUS vs PTBD:Two meta-analyses compared EUS-BD and PTBD after failed ERCP or an inaccessible papilla for malignant biliary obstruction (Table 2). In the meta-analysis by Moole et al[22], 3 studies were included[34,54,55]. The pooled odds ratio for successful biliary drainage was higher in EUS-PD versus the PTBD group and the difference for overall procedure related complications was lower. Other studies found EUS-BD to be superior[55]or have comparable efficacy[54]with lower[54]or comparable[54]adverse event rates, need for reintervention and costs. Sharaiha et al[56]included 6 studies[34,54-59]in their meta-analysis (2 studies were published only in abstract form). There was no difference in technical success rates between the two procedures but EUS-BD was associated with better clinical outcomes, fewer post-procedural adverse events and a lower rate of reintervention. They found no difference in length of hospital stay after the procedures, but EUS-BD was more cost-effective[4]. In 2018, a retrospective showed similar results with the additional finding of a shorter hospital stay for EUS-BD[60].

When ERCP fails to achieve biliary drainage, EUS-guided BD seems preferable over PTBD if the required expertise and logistics are available. The additional advantages are the avoidance of external drainage catheters and the option of performing the procedure under the same sedation as the attempted ERCP.

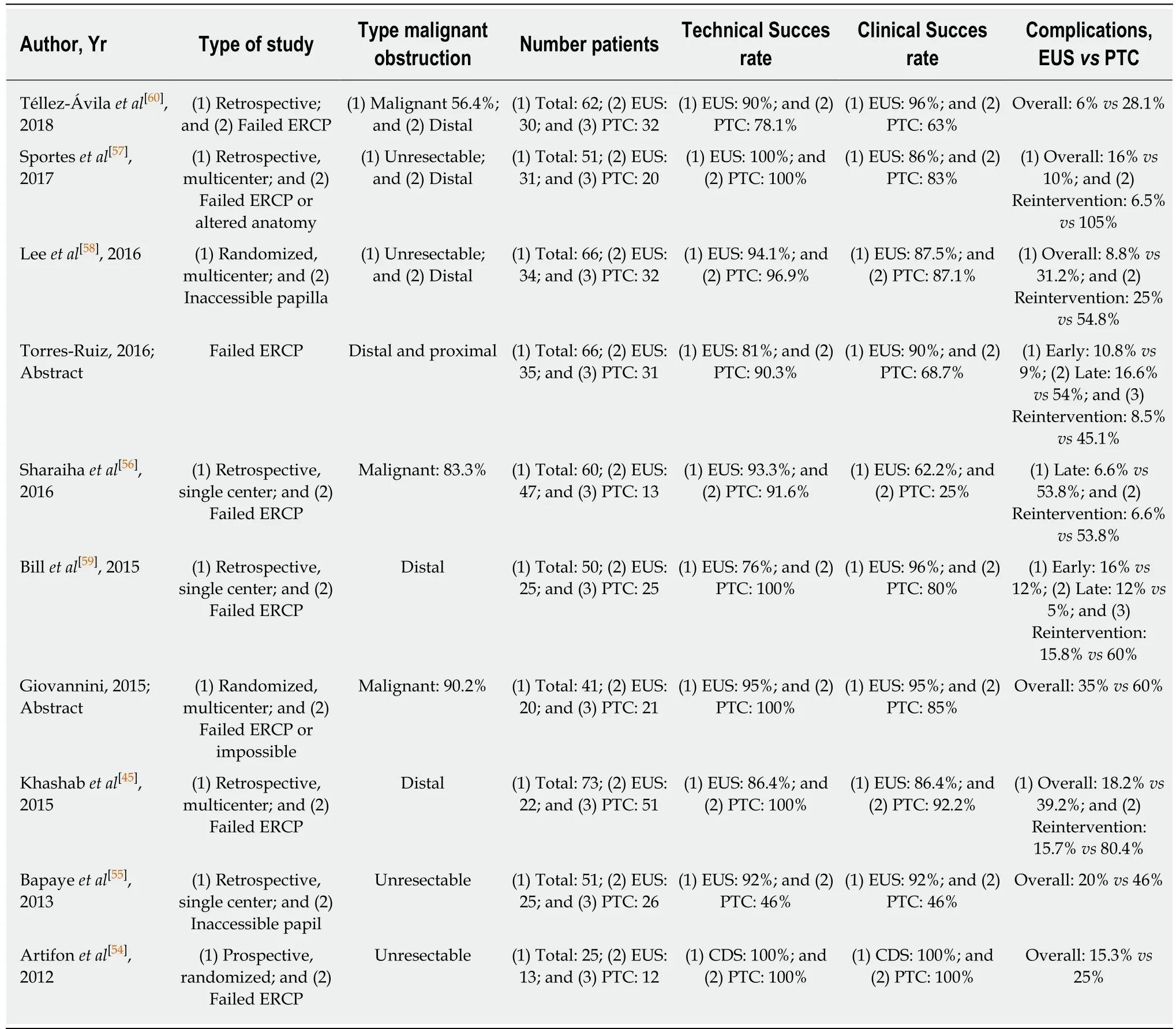

EUS vs ERCP:A limited number of studies reported results for primary EUS-guided BD without prior ERCP (Table 3). Nakai et al[61]performed EUS-HGS in 33 patients with gastric outlet obstruction, surgically altered anatomy or history of ERCP-related adverse events. The procedure appeared safe and effective. These findings have also been confirmed for primary EUS-CDS[62]. Kawakubo et al[63]found comparable technical success rates with ERCP for EUS-CDS as a first-line treatment for patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction, and a significantly decreased rate of acute pancreatitis in the CDS group.

In 2018, the results of 3 prospective, randomized trials comparing primary EUS-guided BD with ERCP were published. All of them described similar technical success rates and clinical outcomes. Paik et al[5]found lower rate of adverse events in the EUS-guided BD group, including post-procedural pancreatitis. This study did not exclude patients with duodenal obstruction or altered anatomy and also performed EUS-HGS.The study demonstrated a lower need for reintervention and higher rate of stent patency in the EUS-guided BD group. The latter finding was attributed to lower risk of tumor ingrowth and/or overgrowth with transmural stenting bypassing the site of malignancy[5]. Bang et al[6]and Park et al[7]reported similar rates of adverse events,reinterventions and stent patency. In the EUS-guided BD group stent occlusion was commonly caused by migration[63]or food impaction[6]. Paik et al[5]reported that the median procedure time and length of hospital stay was shorter with EUS-BD. Park et al[7]found no difference in procedure time between the techniques.

Table 2 Studies comparing endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography

Taking these studies together it would be reasonable to consider EUS-BD as the primary biliary drainage approach in certain situations where the risk of ERCP failure or adverse events is substantial.

Benign biliary obstructive disease

The first report on EUS-BD for benign biliary obstructive disease was published in 2005[64]. In this report, a “neopapilla” was created under endoscopic ultrasound guidance near to the original papilla to extract bile duct stones. After this report,several case series describing the EUS-ERCP rendez-vous technique included patients with benign diseases such as bile duct stones or ampullary stenosis[26,65,66]. Ahepaticogastrostomy has been proposed as a technique to obtain biliary access for antegrade interventions (stone extraction, dilatation of the bilioenteric anastomosis,etc.) in patients with surgically altered anatomy (roux-en-y gastric bypass, Whipple intervention, etc.)[67,68].

Table 3 Studies comparing primary endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography

COMPLICATIONS

Despite the fact that procedure-related complications of EUS-BD appear to be lower than for PTBD and potentially also than for ERCP in selected indications (see above),it remains an invasive procedure with potentially serious adverse events. These may include a pneumoperitoneum (always perform the procedure under CO2 insufflation), bile peritonitis, biliary gastritis, haemorrhage, cholangitis, stent obstruction and (life-treatening) stent migration. Procedure-related deaths have been reported[22,69]. The adverse event rate tends to decrease with the learning curve[22]. For this reason, we believe that EUS-BD should only be performed in referral centres with high volume experience in EUS and ERCP.

CONCLUSION

In patients with malignant bile duct obstruction, EUS-BD is a viable option in cases where ERCP has failed, in the context of surgically altered anatomy or in patients with an inaccessible papilla due to tumoral invasion. Based on the results of three randomized studies, EUS-BD might be a reasonable alternative to ERCP as the firstline procedure in patients with distal malignant bile duct obstruction.

The role of EUS in establishing biliary drainage where obstruction is due to a benign aetiology is rather limited (less than 5% in most case series)[22]. A rendez-vous approach can be particularly useful in patients with an accessible duodenum in whom the papilla cannot be identified or cannulated (e.g., in the case of a large duodenal diverticulum). Temporary transmural drainage with a choledochoduodenostomy or hepaticogastrostomy and subsequent antegrade treatment after the fistula tract has matured has been described (especially in patients with altered anatomy due to previous surgery) but should be reserved for cases in which less invasive alternatives have failed.

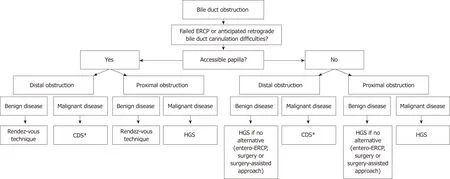

In Figure 2, we propose a practical flowchart that suggests roles for EUS-BD within the current management algorithm of benign and malignant biliary obstruction.

Figure 2 Proposed algorithm that positions endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage in the current management of biliary obstructive disease. *The choledochoduodenostomy can be combined with a duodenal stent or an endoscopic gastrojejunostomy if indicated. CDS: Choledochoduodenostomy; HGS:Hepaticogastrostomy; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography.

Given the development of EUS-BD over the last few years, it is anticipated that novel dedicated endoscopic devices and tools will be released. New LAMS allowing puncture, tract dilatation and stent delivery in one step, provide significant advantages over needle/guidewire/dilation and stent delivery techniques. A steerable wire specifically designed for EUS-BD is being developed (oral communication, Boston Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). A 4 cm partially covered stent for CDS is expected mid 2019 (oral communication, Taewoong Medical, South Korea). A one-step dedicated stent introducer with a push-type dilator without the need for pre-dilatation or use of electrocautery has recently been described and will,when it becomes available, further facilitate EUS-guided transmural biliary drainage[5].

Future studies should address whether EUS-BD should be the first-line therapy(rather than ERCP or PTBD) in patients with malignant bile duct obstruction with preserved left-right intrahepatic bile duct communication.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy的其它文章

- Safety and efficacy of over-the-scope clip-assisted full thickness resection of duodenal subepithelial tumors: A case report

- Role of pancreatoscopy in management of pancreatic disease: A systematic review

- Narrow band imaging evaluation of duodenal villi in patients with and without celiac disease: A prospective study

- Age, socioeconomic features, and clinical factors predict receipt of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in pancreatic cancer

- No significant difference in clinically relevant findings between Pillcam® SB3 and Pillcam® SB2 capsules in a United States veteran population

- Spectrum of gastrointestinal involvement in Stevens - Johnson syndrome