一捧“彩虹般的花束”

—— 纪念阿尔多·凡·艾克诞辰100周年

2018-12-28WrittenbyAlexanderTzonisLianeLefaivre

Written by Alexander Tzonis & Liane Lefaivre

黄卿云 译 Translated by Huang Qingyun

2018年,是阿尔多·凡·艾克(Aldo van Eyck,下文称“凡·艾克”)(1918~1999)诞辰100周年。在创造性与毁灭性并存的20世纪——这个前无古人的,甚至可以称得上重新定义了建筑的时代,凡·艾克无疑是最激励人心、最诗意盎然的人文主义建筑师之一,其设计思想及建筑作品从根本上塑造了当代人认识和理解世界的视角。与20世纪其他主要建筑师相比,凡·艾克的建筑作品数量相对较少,但他设计背后的思索却宏大而深刻。诚然,人们对他设计的评价有褒有贬:有的作品因功能不便而被批判,但也不乏设计表达一气呵成、深受使用者喜爱的创作。但直到今天,他的形式语汇和文本语言仍被有意或无意地应用于当代建筑设计实践中,影响持续而广泛。

凡·艾克并不拘泥于某种单一的建筑主义或生活方式,他追求多种互补交叉观点的融合,并将其喻为一捧“彩虹般的花束”。

1

凡·艾克的父亲是荷兰人,母亲是荷兰犹太人。他在英国度过了自己大部分的年轻时光。第二次世界大战期间,他逃离被德军占领的荷兰,在瑞士苏黎世联邦技术学院(ETH)学习建筑,并于1945年顺利获得学位。同年二战结束,旷日持久的战争和自一战后执政者的忽视,使战区大量民众流离失所、无家可归。因此,作为战后恢复的第一步,这些地区展开了大规模的生产建设活动。

起初,人们战后重建与恢复的决心坚定,但到了20世纪50年代中期,这种热情却逐渐衰退,甚至滋生出一些不满情绪。当时,城市建设发展的进程是由可量化的“客观事实”衡量的,例如新建建筑的数量、规模、面积等。1971年,西蒙·库兹涅茨(Simon Kuznets)创造性地将“国内生产总值”(GDP)这一概念作为量化国家生活水平的工具,并获得了当年的诺贝尔经济学奖。但他同时警告说,这一数学模型并不足以区分“数量增长和质量提升”之间的差别,“换言之,GDP本身无法为人类带来幸福,克服困苦”[1]。

彼时,越来越多的人自发组织抗议游行,呼吁更宽松、非压迫的社会环境。刚刚跨出大学校门的凡·艾克也加入其中。在早期的一篇文章中,他写道:“(现实中的)贫民窟虽已消失”,但是“精神上的贫民窟仍千疮百孔”。他当时所处的社会环境很大程度上催生了这些观点。那时,苏黎世作为战争中立国瑞士的一座城市,汇聚了从欧洲各国流放至此或主动前来的知识分子、先锋派艺术家、国家间谍等,是名副其实的各阶层、多文化集合体。凡·艾克在这座复杂而斑斓的国际都会中持续成长,与不同文化背景的人交往,他自己也曾几易国籍。

因此,当个人思维观念逐步建立,凡·艾克主观上渴望寻求多种观点“协调”统一,同时也尽量避免被“还原论”教条所束缚。早在苏黎世的学生时代,凡·艾克就接触到了生于奥地利的以色列哲学家马丁·布伯,他的论著给了年轻的凡·艾克极大启发。在两次毁灭性的世界大战期间,马丁·布伯研究的是日常生活中的重商主义,这一研究对象也极具毁灭性。他指出,“物”具有“去人性化”的作用,应被称为“它”。正是“它”的存在,破坏了人类之间的关系,将“我-你”分立,并忽视两者“之间”(zwischen)的互补与联结,进而阻碍了两者的对话。而探讨对话、互补与协调间的些微差异,则成为凡·艾克的研究与实践中至高无上的追求,渗透到他学术生涯的各个方面。

图1:凡·艾克在自宅工作室展示自己的非洲工艺品收藏(亚历山大·佐尼斯 摄)Fig.1:Aldo van Eyck in his home-studio pointing to his African artifacts collection (photoed by A. Tzonis)

图2:阿尔多·凡·艾克与汉妮·凡·艾克在自宅工作室(亚历山大·佐尼斯 摄)Fig.2:Aldo and van Eyck in their home-studio (photoed by A.Tzonis)

2

在苏黎世联邦技术学院学习期间,凡·艾克选择了毕业于巴黎美院(PBA)的古典主义学者拉方斯·拉韦里埃(Alphonse Laverriere)教授作自己的导师。同时,他进入由历史学家齐格弗里德·吉迪翁(Siegfried Giedion)的妻子卡罗拉·吉迪翁-韦勒克(Carola Giedion-Welcker)创立的社交圈,并在她的引荐下,接触到当时的现代艺术与艺术家们。1944~1947年间,凡·艾克用自己的积蓄收藏了一批艺术作品,其中包括毕加索(Picasso)的雕塑《苦艾酒瓶》(Verre d’Absinthe)和版画《弗朗哥的梦幻及谎言》(Songe et Mensonge de Franco),让·阿尔普(Jean Arp)、伊夫·唐吉(Yves Tanguy)、皮特·蒙德里安(Piet Cornelies Mondrian)的画作,还有一些巴黎先锋艺术家的作品、非洲面具及手工艺品等(图1、图2)。

1946年,凡·艾克再次回到荷兰,受雇于阿姆斯特丹公共工程发展办公室,成为最著名的现代建筑倡导者之一、战前国际现代建筑协会(CIAM)领导人科内利斯·范伊斯特伦(Cornelis van Eesteren)麾下的一员。这份工作,使凡·艾克将自己对于建筑的思索及理解应用到具体的设计实践中。

3

科内利斯·范伊斯特伦在阿姆斯特丹任职期间,承担了这个城市内大规模的重建任务。诚然,他延续了战前的现代建筑与城市规划理念,采用自上而下的“整体”规划方式,旨在最高效地安置“最大数量的居民”。但这次,他邀请凡·艾克负责为这个庞大居住项目设计游乐场地,并鼓励他带着批判性的视角,对居民的需求作出最自然、灵活和直接的应对。

一方面,凡·艾克接受了科内利斯·范伊斯特伦合理的整体功能及空间设计框架。同时,他也私下与“眼镜蛇派”(CoBRA)等战后先锋艺术团体进行合作。

最终,凡·艾克选择在城市中的“遗忘之地”置入游乐场地。如1954年约翰·沃尔克(John Volker)所报道,那些在战争中“被道路工程师和拆迁承包商遗弃的孤岛”,在凡·艾克眼中,却是(人类生活的)机遇。科内利斯·范伊斯特伦委派激进主义景观设计师杰科芭·米尔德(Jacoba Mudler)协助凡·艾克的工作,两人对待设计的想法不谋而合。

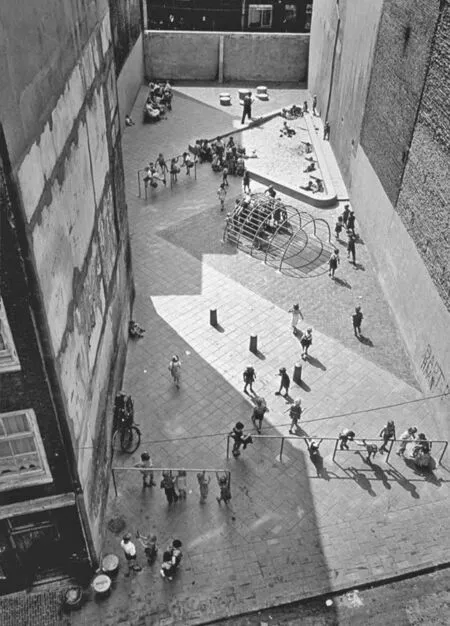

与大多数战前的设计手法不同,凡·艾克没有使用在远离场地的工厂中生产的建筑部件,而是就地、就近取材。这种实用主义的解决方案,在那个“为数字而建设”的高产能高消耗的时代,无疑是一条新颖的思路(图3)。

同“重建”时期不愿遵循抽象的“内在错觉”(萨特原话)指导的新现实主义作家、导演、摄影师等人一样,凡·艾克也更倾向于关照现实中的“特定场景”,“让设计与真实世界之间既疏离又紧密”。

英国建筑师约翰·沃尔克曾预言:这些看似“从头开始”的简单项目将对城市产生漫长持久的影响,甚至将引导城市主义者推进“更广泛、更复杂、更社会化同时也更昂贵的城市发展道路”。

在凡·艾克最长的一篇手稿“儿童、城市和诗歌”中,他把儿童写作社会忽视与压迫的受害者。他眼中的“儿童”,是一种全新的社会运作模式与生活方式中的主人翁——他们代表着好奇心、梦想与不循规蹈矩,是虚伪的既有规则的反抗者,也是无尽创造力的拥有者。在凡·艾克看来,儿童游乐场地的置入并不仅仅是城市重建工作的一部分,也不只是对城市空间的修复,而且是一种先锋的态度,一份旨在改变城市生活方式的“诙谐”宣言。他希望通过创造“我-你”“之间”的交往空间来改造城市,促进两者之间有意思的“对话”。凡·艾克用一个诗意的比喻来解释这种思想:“一场暴风雪后”,城市焕然一新,曾经被我们忽视的儿童,“成为城市之王”。

事实上,无论是儿童还是成年人,都爱极了凡·艾克设计的游乐场地和活动场。到1951年,阿姆斯特丹城内已建成的游乐场地不下700余处,其中大部分是为了满足邻里空间需求而建造的。现如今,这些游乐场地几乎都已不复存在了。但曾在其中嬉戏过的阿姆斯特丹人会怀念它带来的快乐——它们仍存在于这些人心中。

图3:阿姆斯特丹游乐场,阿姆斯特丹Fig.3:Aldo van Eyck Amsterdam playground

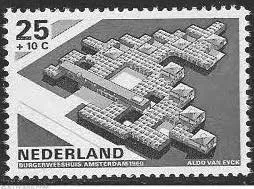

图4:1960年荷兰邮票上的“儿童之家”(1955-1960)Fig.4:Aldo van Eyck Children’s Home, Amsterdam, 1955 -1960. Post stamp, 1960

图5:“儿童之家”,阿姆斯特丹,1955-1960Fig.5:Aldo van Eyck Children’s Home, Amsterdam, 1955 - 1960

4

阿姆斯特丹城市游乐场地设计的影响是有限的。让凡·艾克举世闻名的项目,其实是位于阿姆斯特丹市外的“儿童之家”——一个收留孤儿和破裂家庭儿童的机构。

儿童之家项目在很多方面都与阿姆斯特丹游乐场地相反。游乐场地见缝插针地嵌入拥挤的城市空间,通常是无屋顶的小型构筑物;而儿童之家则是城市郊外空旷的场地中一个带顶的大型多功能综合体,与其毗邻的是大型体育馆、高速公路和国家机场。在这样的场地条件下,甲方要求凡·艾克设计的建筑能够填补孩子们生活的空缺,为无家可归的他们带去家庭的温暖与城市的认知。

和游乐场地的设计一样,在儿童之家中,凡·艾克也尝试在古典的空间构成和反古典的风格派体系中寻求协调的“对话”,使两者“完美融合”。为了避免通常大尺度机构类建筑内部空间大而无物的通病,他将建筑分解为多个重复的单体,在网格内按照特定模式排布。

这一设计的灵感来自于凡·艾克在造访非洲多贡地区时看到的当地族群住宅:由一个个单体地块拼接交织形成的一片住区。他在其中看到了个人与社会之间真实而紧密的 “对话”。因此,凡·艾克尝试通过重复排列的带圆顶的建筑单体来表达一种“多样而统一”的氛围。事实上,圆顶这一开创性的想法并不来自凡·艾克,而是他当时的助手乔普·凡·斯特(Joop van Stigt)的点子(图4、图5)。

为了适应儿童的使用,凡·艾克还调整了建筑内部空间的尺度。

阿姆斯特丹城内的游乐场地在使用中并未出现功能性缺陷,但在设计上充满“独创性”的儿童之家,却终因拘泥于空间排布的象征意义而(忽略实际使用)成为功能失调的建筑作品。尽管凡·艾克公开了项目设计理念,并亲自拍摄了他和朋友的孩子们在建筑中玩闹嬉戏的照片,以期向社会传递这一作品的深意,但最终,孤儿院还是被搬离了。

但在这些失败尝试的背后,凡·艾克创造性的设计理念与思想依旧对后人产生了深刻的影响。

5

在此后的创作生涯中,积累了更多经验的凡·艾克,仍渴望设计出能够同时满足精神文化需求和实际功能使用的建筑作品。

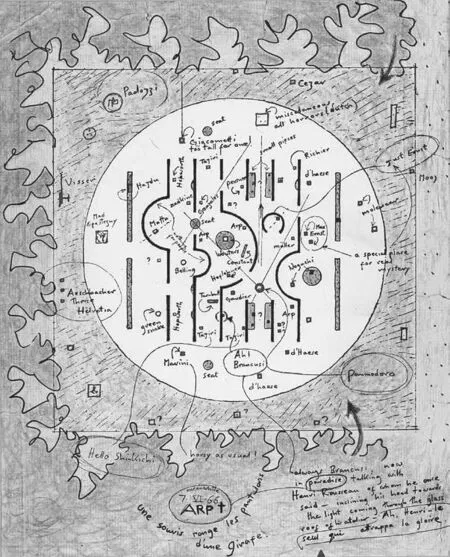

1965~1966年间,凡·艾克为位于阿纳姆的公园设计了一个花园建筑小品——桑斯比克亭(Sonsbeek)。这座室外带顶建筑被用以展出中等尺度的雕塑,建筑毗邻同个公园内由亨利·克莱门斯·范·德·费尔德(Henry Clemens Van de Velde)设计的克勒勒-米勒博物馆(Kröller-Müller museum)(图6、图7)。

建筑由平行排列的墙体组成,平面划分遵循经典的三段式原则。通过墙体开口、曲直墙面的共同作用,营造出似无尽延展的路径、似变幻莫测的流线和一系列连续的空间转折,使人身处其中却难辨始终,到不了中心,也找不到归路。

我们很难去分析这一建筑的功能,因为除了在天空之下展览雕塑作品这一朴素的功能以外,它似乎再没有其他值得称道的功能设置与排布。但毋庸置疑,我们可以讨论这个建筑中的人——无论是建筑师、社会精英、普通民众、学者亦或儿童,都可以在这一空间中享受片刻沉思漫步的“哲思之旅”,如同阿方索·保卢奇(Alfonso Paoluccci)笔下前往科隆那“维尼亚”的卡比托尔山的旅程。但和凡·艾克大部分作品一样,这个设计仍旧像个政治性工具,而没有跳脱象征的寓意。在马丁·布伯的哲学框架下,除了政治功能,它一无所长。

凡·艾克将这个建筑称作迷宫。它并不是代达洛斯建造的那座迷宫,也没有阿里阿德涅循线杀死囚禁于迷宫中的半人半牛怪兽——这座迷宫是没有终点的:在思维的无边旷野中,在路径纠缠的交结处,“我”与“你”撞了个满怀。凡·艾克将这样的瞬间称为“灵光一现”(Eureka)或“顿悟”(Aha!)时刻,而通常这两个词只出现在自然科学探索的过程里。的确,这座迷宫正演绎了智慧、创造力、宇宙与社会关系,还有人类生命本身的意义。

6

20世纪60年代,凡·艾克名声大噪,许多学生和年轻建筑师慕名而来与他共事,其中包括乔普·凡·斯特、特奥·鲍士(Theo Bosch)、皮特·布洛姆(Piet Blom)、赫曼·赫兹伯格(Herman Herzberger)等。到了1970年代,城市管理者也开始关注凡·艾克,请他为城市公共住房建设建言献策。他参与设计了多德雷赫特市和兹沃勒内城的公共住房项目,还有位于阿姆斯特丹的五角住宅楼。在继续尝试于古典的空间构成和反古典的风格派体系中寻求协调“对话”的同时,凡·艾克试图将新的构型作为“填充物”整合进战前的城市肌理中。此外,他也尝试营造介于公共与私密“之间”的空间,为社会交往与对话带来更多可能。

正当凡·艾克的作品呈现出积极的功能组织,并吸引了相当数量的年轻人时,如之前所言,也引来了年轻激进分子的政治反对。他们认为这种做法与先锋派、左翼人士和二战前的新即物主义(Neue Sachlichkeit)建筑师的做法背道而驰,有可能阻碍人类对新生活方式的践行。

6

图6:桑斯比克亭,阿纳姆,1973-1978Fig.6:Aldo van Eyck Sonsbeek Garden Pavilion, Arnhem,1973-1978

图7:桑斯比克亭手绘,《Wel Evenwaardig》封面图Fig.7:Aldo van Eyck, drawing, cover of Wel Evenwaardig,Amsterdam Sonsbeek Garden Pavilion, Arnhem,1973-1978

7

与桑斯比克亭中高度诗意化的思考不同,为单身母亲(现在是任一性别的单身家长)和他们的孩子们建造的胡贝图斯单亲宿舍(1973~1978年)则是一个完全“务实”的实用主义建筑(图8)。同20世纪40~50年代设计阿姆斯特丹游乐场地时一样,凡·艾克将这个项目看作是对城市用地的“填充”和“增置”。

胡贝图斯单亲宿舍的场地区位十分有趣。它是普兰塔区一排典型的布尔乔亚式联排别墅的一部分,同时又临近许多19世纪建筑杰作,例如阿姆斯特丹动物园、贝尔拉赫钻石工人联盟等;其一街之隔就是荷兰舍大剧院。事实上,这片场地上曾经矗立的建筑,是塔木德索拉犹太教堂。

在这样的场地条件下,凡·艾克越发关注建筑与阿姆斯特丹地域文脉之间的联系,就如同这里的居民最终与生活环境融为一体。在设计中,他没有使用复杂的几何排布,也不追求构型的协调整合。相反,凡·艾克在建筑物表面大面积使用彩色涂刷,使建筑真成了“彩虹般的花束”。他说,对于那些被长期孤立、流离失所的人们而言,这象征着“快乐、感动与积极乐观”。他也希望通过这种方式,营造出“回家的氛围”、充满活力的社区和自然而然的交流。

项目竣工后不久,新泽西理工学院决定授予凡·艾克荣誉学位。在授予仪式后的演讲中,凡·艾克公开展示了这个项目。演讲地点离纽瓦克工业中心“铁路区”不远,之所以这么称呼,是因为这个区域被铁轨层层包围。

参与仪式的观众包括新愤青时代成长起来的部分国际建筑师,和支持凡·艾克的学生们。他们将他视为建筑道路的先行者和保持旺盛建筑创造力的代言人。

彼时,战后重建时期唯物主义设计师大行其道的时代已经翻篇,后现代主义正甚嚣尘上。理论家陶醉在建筑自律性中,忽视人类对于功能的根本需求。

因此,当凡·艾克没有提及诗意,而是强调“对更好功能运作的需要”、“这个时代更应追求多层次的功能”时,台下的观众都大吃一惊。

8

欧洲太空技术与研究中心(ESTEC,1984-1989),是位于诺德维克的科研综合体,被称为欧洲的NASA。它是凡·艾克建筑生涯最后期的作品之一,也是其最为复杂的项目之一。建筑包括一个餐厅、一个技术文件中心和一系列办公楼。ESTEC的主管马西莫·特雷拉(Massimo Trella)聘请凡·艾克作为这一建筑综合体的设计师。在此次设计过程中,凡·艾克的妻子汉妮·凡·艾克(Hannie van Eyck)扮演了越发重要的角色。

凡·艾克并没有忘记自己对“多层次的功能”的追求。在面对这个庞杂的科研中心设计时,他既跳脱了传统的建筑设计正交网络,也没有像在以往项目中那样,考虑古典与反古典的融合。他向意大利手法主义拥趸者罗伯特·文丘里(Robert Venturi)学习,尝试设计一个非线性、多节点的空间构成体系。它在保持空间完整性的同时,加强组团多样性,从而创造更多“我-你”之间的交往空间。

尽管凡·艾克本人不是一个严格意义上的科研工作者——他和代尔夫特理工大学之间的合同是定期续签的,事实上,他也从未在学校有过一个终身职位——但是他深知科学界长久以来存在的问题。当路易斯 · 康(Louis Kahn)在美国加利福尼亚州拉荷亚与乔纳斯·索尔克(Jonas Salk)进行关于索尔克研究所的讨论时,这个问题就已被提出。近年来,在世界各地的高精尖技术研究实验室中,关于它的讨论也越来越多。

科学研究者早就意识到,需要一个介于内部和外部之间的场所,让彼此沟通对话。科学家看似都倾向于生活在科幻与想象中,每个人承受着巨大的孤独各自为战,进而越来越精细化、独立化。他们研究着互不相关的理论,像是一个个“封闭”的个体,互相之间缺乏理解与交流。然而,众所周知,大多数的奇思妙想都是在跨越知识壁垒的思想碰撞中产生的。当科学(和其他人类学科一样)变得高度分化,随之而来的就是分裂、坍塌与破碎。借用维特根斯坦(Wittgenstein)的比喻,现代科学越是成功地在人类知识的“郊区”开荒拓野,我们就越将处在“无知”的危险境地。

事实上,(这种分化)正是凡·艾克在建筑设计中极力避免的。自阿姆斯特丹游乐场地设计伊始,在凡·艾克建筑生涯的大部分项目中,无论是追求诗意表达抑或功能实用,他想呈现出的,始终是那一捧“彩虹般的花束”。

非常荣幸,我们与阿尔多·凡·艾克先生本人有过面对面的学术交流。1962年在哈佛大学,当时还在耶鲁大学读书的亚历山大·佐尼斯第一次见到了凡·艾克先生。而利亚纳·勒费夫尔与凡·艾克的第一次见面,则是1985年前后在代尔夫特。1985~1999年间,学界内关于凡·艾克设计理论与实践的讨论十分热烈,其中也涉及对他建筑作品的实际保护问题。利亚纳·勒费夫尔和亚历山大·佐尼斯都曾与凡·艾克先生保持书信交流,讨论我们当时正在创作的一本书。但遗憾的是,凡·艾克先生未等到这本书出版,就于1999年1月14日离世。同年数月后,书籍才付梓出版。我们三人往来交流的书信文件被收录在《亚历山大·佐尼斯和利亚纳·勒费夫尔档案》一书中。

注释

[1]1971 年度瑞典中央银行纪念诺贝尔经济科学奖得主,西蒙 · 库兹涅茨,诺贝尔奖获奖演讲,1971 年12 月11 日。

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Aldo van Eyck (1918-1999), one of the most inspiring, poetic, and humane architects of the past century, a creative and destructive century that redefined architecture as no other era before. Aldo’s buildings and texts shaped in fundamental ways the way contemporary people look and interpret the world. The number of his projects are relatively few, in comparison to other major XX century architects, but the complexity of the design thinking is vast. Some marked by functional failures some performing remarkably well and beloved by their users. Yet, his visual concepts and their verbal counterparts have been absorbed into contemporary design and continue to have, consciously or intuitively, a universal presence.

Aldo did not stand for any single doctrine of architecture, or life. He chose to offer a synthesis of complementary views, what he called a “rainbow bouquet.”

1

Son of a Dutch father and a Dutch-Jewish mother, Van Eyck spent his early years in England and the war years in Switzerland studying architecture in ETH in Zurich away from occupied Netherlands. He received his diploma 1945, the year the war ended and the year of the beginning of a vast campaign of building for the ‘great number’ of homeless, because of the war and of the years of political neglect, since the 1920s.

The drive to re-construct and construct was massive. However, by the middle of the 1950s, the enthusiasm about the reconstruction waned and there were signs of discontent. Progress was measured by counting‘objective facts’, such as numbers, volume,and size of the new buildings. As Simon Kuznets, the Nobel Prize-winning inventor of the concept of the ‘Gross Domestic Product’which served as the tool that was used to measure a country’s standard of living by calculable facts, warned in 1971, the problem was that his model was not sufficient to distinguish ‘between quantity and quality of growth …’ In other words, it did not have the power to bring about human happiness,to overcome oppression.

Aldo, just out of the university, joined the growing protest in search for a non-oppressive environment. In an early text he wrote ‘the slum has gone’, but ‘behold the slum edging into the spirit’. His opinions emerged out of the most stimulating environment of Zurich at that time. Zurich,a city of neutral Switzerland during the war, became a multilayered hub of exiled or self-exiled intellectuals, Avant Garde artists,scientists, and spies. He thrived in this rich complex cosmopolitan setting himself as someone who had changed countries several times and encountered people of very diverse origins and identity.

Thus, in developing his own individual way of thinking, he searched for ‘reconciling’ diverse points of view and avoiding any reductive dogma. In this he found stimulation and advice in the writings of Martin Buber, an Austrian-born Israeli philosopher,which he discovered in Zurich as a student.Working between two catastrophic world wars and equally destructive commercialism of everyday life, Buber identified the ‘dehumanizing’ effect of ‘objects’, he called them the ‘it’ that destroys human relations, the ‘I and Thou’ rather than acting as the ‘between’ (zwischen)’, ‘where I and you meet’, enabling ‘interhuman’ (das Zwischenmenschliche) dialogue. Dialogue,complementarity, and reconciliation in difference became Aldo’s overriding objective in all aspects of his intellectual life.

2

As a student at the ETH he chose to follow the classicist professor, Alphonse Laverriere, a Paris Beaux Arts graduate. At the same time, he entered the circle of Carola Giedion-Welcker, wife of the historian Siegfried Giedion, who introduced him to modern art and artists, acquiring, between 1944 and 1947, through his own savings, Picasso’s Verre d’Absinthe and Songe et Mensonge de Franco, an Arp, a Tanguy, a Mondrian,and also, like the Avant Garde artists in Paris,African masks and artifacts.(Fig.1, Fig.2)

He applied the same approach to his professional work when he returned to the Netherlands in 1946 employed by the Office for Public Works in Amsterdam under the direction of one of the most prominent proponents of Modern Architecture and a CIAM leader before the war, Cornelis van Eesteren.

3

In his Amsterdam post, Van Eesteren had undertaken the colossal task of reconstruction. True to the vision he had espoused before the war, he applied a top-down “total”planned approach to house ‘the greater number’ most efficiently. Yet, he invited Aldo to follow his critical ideas about ground up, spontaneous, flexible, and direct reaction to the needs of citizens, offering him the responsibility to introduce playgrounds in his vast residential scheme.

Aldo accepted the rational overall programmatic and spatial framework of Van Eesteren while the same time collaborating individually with rebellious art groups such as CoBRA.

He inserted his “playgrounds” in“left-over places” in the voids of sites abandoned during the war. In the words of John Volker reported in 1954, he recruited the ‘formless islands left over by the road engineer and the demolition contractor,’perceiving them as opportunities. Similar ground-up ideas were held independently by Jacoba Mulder a landscape activist planner who was appointed by Van Eesteren also to collaborate with Aldo.

In contrast to most prewar approaches to architecture recommending the use of industrial components produced usually in distant plants,Aldo employed plain, locally available materials found close to the site, in his pragmatic solution demonstrating the idea of alternatives in a mass produced and mass consumed environment‘for the great number.’(Fig.3)

Like the neorealist writers, filmmakers,and photographers of the period of ‘reconstruction’, Aldo rather than following ‘the illusion of immanence’, of abstract formulas,to quote Sartre, reflected on the reality of each given ‘situation’, ‘alienated but also engaged in the world’.

Volker, an English architect wrote about the long-term implications of these from the‘ground up’ humble projects predicting that they will guide urbanists in ‘more extensive, socially more complex, more expensive developments’.

In his most lengthy manuscript ‘The child,the city, the poet’ Aldo saw the child as a victim of neglect and oppression. For him the ‘child’stood as a hero representing a special approach to life and society, as a champion of curiosity,dreams, chaos, resistance to fake rules, a force of endless creativity. Thus, the playgrounds for him were not only a remedial, work part of the reconstruction program but also avantgarde agents, a“ludic” manifesto for changing the way of living in the city. He expected them to transform the city bringing in the ‘between’ where ‘I and you meet’ in ludic ‘dialogue.’ He used a poetic metaphor to explain the idea, the way, ‘after a heavy snowstorm’, the city is revolutionized the neglected children taking over ‘becoming the Lord of the City’.

Children and adults loved Van Eyck’s playgrounds, or speelplatsen. No fewer than 700 were built in Amsterdam up to 1951,most of them in response to neighborhood demands. Few of these projects still stand.Many Amsterdamers still alive who played in them are nostalgic of the happiness these structures offered them.

4

The reputation of the Amsterdam playgrounds was limited. The project that made van Eyck world famous was the Children’s Home,an institution for orphans or children of broken homes, located outside Amsterdam.

In many respects the Children’s Home was the opposite of the playgrounds. While the Amsterdam playgrounds were small roofless minimal structures occupying crowded interstitial urban voids, the Children’s Home was a large multifunctional complex under one roof located in a vast open area, outside the city’s periphery, its closest neighbors being a stadium, the open highway, and the national airport. It was within this context that van Eyck was asked to fill in the absence in the life of children deprived of a home by offering them a community of homes, and a city.

As with the playgrounds, Aldo tried to compose the plan of the Children’s Home as a dialogue reconciling the classical canon of spatial composition with the anticlassical De Stijl system, ‘joined in a perfect amalgam.’Avoiding the authoritarian effect of large scale of institutional buildings, he conceived a scheme consisting of repetitive individual units united in a cumulative collective pattern.

The idea emerged out of his visit to the Dogon region in Africa where the single homesteads form a remarkable complex of a whole.Aldo saw in the Dogon architecture a genuine,solid ‘dialogue’ between the individual and the social whole. Thus, he tried to give gave to the project a sense of a of ‘unity in multiplicity’ by introducing into the scheme repetitive individual places covered by repetitive domes.In fact, the originF of the ingenious idea of the dome was not his but of his assistant at that time, Joop van Stigt. (Fig.4, Fig.5)

He also adapted the scale of the interior of the building reducing it to the dimensions of the children.

On the other hand, as opposed to the Amsterdam Playgrounds that presented no functional problems, the ‘inventions’ of the Children’s Home remained symbolic gestures that lead to a dysfunctional facility.Despite the publicity of the ideas and the photographs, taken by van Eyck himself featuring his own and his friends’ children trying to demonstrate the virtues of the project,the orphanage moved out of the building.

These failures, however, did not stop the influence of his theoretical concepts and ideas behind their abortive implementation.

5

Later in life, a more experienced Aldo designed and constructed structures which excelled equally as cultural manifestoes and as functional products.

During 1965-1966, Al do designed in the middle of a splendid park in Arnhem a garden pavilion, Sonsbeek, a shelter and a setting for outdoor exhibitions of medium size sculpture,not far from the Kröller-Müller museum, a building designed by Henry Clemens Van de Velde in the middle of a splendid park. (Fig.6, Fig.7)

The work is composed by is a series of parallel planes organized within a classical tripartite schema. The walls are penetrated by openings forming an endlessly branching out promenade, a shifting pattern of winding paths, a succession of turnings making hard to find one’s way whether to penetrate to the center, or, from there to reach the exit.

It is strange to talk about the functionality of the project where there appeared to be hardly any serious function to talk about,apart from displaying objects of art under the sky. Without doubt however one can talk about the people - architects and elite and not elite public, senior academics and children - that equally enjoyed using the structure for meditative walking, to ‘philosophize,’as Alfonso Paolucci wrote in his account of his visit to Colonna’s vigna on the Capitoline Hill. But as with most of van Eyck’s oeuvre, it is also a project for action and play an allegory and an instrument about politics, in the sense Martin Buber’s philosophical texts functioned as a political program.

Aldo talked about the project as a labyrinth, but there is no terminal point here, a labyrinth with no Minotaur, Daedalus, or Ariadne’s thread. What one discovers in the wilderness of one’s mind, in the knot of the paths, is the coming face to face with the other. Aldo called that the effect of ‘eurika’ or ‘aha!’ a term usually applied to scientific discoveries. Indeed, the labyrinth is synonymous with intelligence, creativity, the dialogical social cosmos, human life itself.

The reputation of van Eyck increased considerably during the 1960s attracting students and young architects to work with him among them,Joop van Stigt, Theo Bosch, Piet Blom, and Herman Herzberger but he also attracted in the 1970s administrators eager to have him contribute in the sector of public housing as in the case of housing in Dordrecht, in the inner city Zwolle, and in the Pentagon in Amsterdam. While continuing his formal spatial explorations trying to reconcile classical and anticlassical-De Stijl canons, he also tried to integrate the new structures as ‘infill’ to the pre-existing,pre-war regional urban tissue. In addition, he also tried to generate ‘in-between’ private and public places for social dialogue.

While functionally positive, appealing to a considerable number of young people, as we said, the approach met also with political opposition from young radicals who found it obstructing the search for realistic new ways of life as the Avant Garde, left wing, pre-WWII Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) architects did.

7

In contrast to the highly ‘poetic’ character of the Sonsbeek pavilion, the Hubertus home (1973-1978) for single mothers (now for single parents of either sex) and their children, is a ‘pragmatic’facility. (Fig.8) As in the case of the Amsterdam playgrounds of the 1940s-1950s, Van Eyck designed it as an “incremental”, “in fill”,

The building stands in one of the most interesting districts of Amsterdam. It is part of a row of typical bourgeois town houses in Plantage,an area associated with 19thcentury architectural masterpieces such as the Amsterdam Zoo, Berlage’s Diamond Workers Union and theaters such as the Hollandse Schouwburg, just across the street from Hubertus. The site itself of the project was once occupied by the Talmud Thora Synagogue.

Aldo, became particularly concerned with making the building to belong to the ‘regional’ Amsterdam context, like its inhabitants to become part of the same milieu. He did not apply any of the complex geometrical juxtapositions and shape reconciliations. Instead, he extensively used color, laying over the structure of the building a polychromic “rainbow bouquet”, in his words an “icon of joy, affection,and optimism” for the aliened and displaced, creating what he called a “sense of homecoming”, fresh community, and emergent dialogue.

Van Eyck, invited to be given an honorary degree,presented the project in a speech given soon after its completion at the New Jersey Institute of Technology,- not far from the Iron-bound area, in the heart of the slam in the industrial neighborhood of Newark, named so because it is bounded by rail-tracks.

The audience consisted of well-established international architects of the new angry young men generation and students who applauded Van Eyck as their precursor an ally, and as a spokesman of the sustained living consciousness of architecture.

From the point of view of the architectural audience, this was the time of post-modern narcissistic ideologues of the autonomy of architecture who disregarded human functional needs, very different from the audience of the ‘materialistic’ designers of the times of reconstruction that Van Eyck confronted in the post war years of reconstruction.

Van Eyck surprised the audience by talking not about poetry but about the ‘need of better functioning,’ the need for function being ‘on more levels this time.’

8

ESTEC, (1984~1989), a research complex located Noordwijck, the Europe’s equivalent of NASA,was one of the last projects of Aldo and perhaps one of the most complicated. The facility contained a restaurant, a technical documentation center, and a series of office towers. Aldo was hired by the director of ESTEC, Massimo Trella. Hannie van Eyck, Aldo’wife, came to play increasingly an equal role in the design process.

Without forgetting his plea for ‘function on more levels’, Aldo, departed in this sophisticated research center from the orthogonal coordinates building systems, classical or anti-classical he used in his previous projects. Like Robert Venturi, a rigorous student of Italian Mannerism, he tried to experiment with a complex non-rectilinear, eleven-point, spatial coordination system that did not permit the compartmentalization of the place while enhancing the diversity groupings and the I and You of human community.

Although he was not a typical academic— his contract with the Delft University of Technology had to be renewed periodically and he was never offered a permanent post, — Van Eyck understood the deep problems of a scientific community. The question had already been identified by Louis Kahn and Jonas Salk in their discussions about the Salk Institute, in La Jolla in California, and it is increasingly discussed today in leading, cutting edge technology research laboratories.

Scientists have long realized the need for a place that can sustain a dialogue internal and external to the society of research. Because scientists appear to have the tendency to live in a world of fantasy and dream, pursuing their problems privately and often in extreme isolation producing in this manner increasingly differentiated, specialized, ‘incommensurable’ theories, closed ‘objects’, making mutual intelligibility and communication impossible.Yet, it is well known that most new ideas spring by leaping over knowledge barriers, not by solidifying them. When science, like any other human endeavor,becomes a highly divided, it becomes divisive, when it becomes shattered it shatters in turn. To borrow Wittgenstein’s metaphor, the more scientists succeed erecting elegant isolated ‘suburbs’ of knowledge, the more they run the danger to turn the City of Knowledge it into a slum.

图8:胡贝图斯单亲宿舍,阿姆斯特丹,1973-1978Fig.8:Aldo van Eyck Hubertus Home, Amsterdam 1973 -1978

This is exactly what Aldo tried to prevent to happen through architectural means he applied in his Amsterdam playgrounds and through most of his poetic or pragmatic projects offering as alternative a“rainbow bouquet.”

(Footnotes to come)

We were very privileged to have met in person Aldo van Eyck and share ideas with him. Alex met him first at Harvard, while a student at Yale in 1962, Liane,in Delft in at around 1985. During the second part of the 1980s and the 1990s contributed a number of articles on Aldo and his projects involving theoretical but also practical problems of conservation of his buildings.Both Liane and Alex met and exchanged letters with him about a book they were preparing. Unfortunately,Aldo never saw the book published. He died 14 January 1999. The book was published a few months later,1999. The documents of their exchanges are deposited in the Tzonis and Lefaivre Archive.

Note

[1]The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 1971. Simon Kuznets, ‘Prize Lecture to the memory of Alfred Nobel’, December 11, 1971.