巴塞罗那:全尺度的都市规划之路

2018-10-31JoanBusquetsWrittenbyJoanBusquets钱丽源TranslatedbyQianLiyuan

Joan Busquets 文 Written by Joan Busquets 钱丽源 译 Translated by Qian Liyuan

概述

巴塞罗那是欧洲历史悠久的地中海城市典范,是加泰罗尼亚自治区2000多年以来的省会,正如其他欧洲南部城市,都具显著的形态特征和城市形成轨迹:随着人口增长,城市的扩张延续着原有的历 史城市形态,而不是空间的重组。

直至2012年,巴塞罗那市区面积达到98.21平方公里,拥有162万常驻人口,都市区面积为636平方公里, 320万常驻人口。其所在的加泰罗尼亚自治区有近一半的人口居住在仅占自治区面积1.98%的巴塞罗那市城市中。

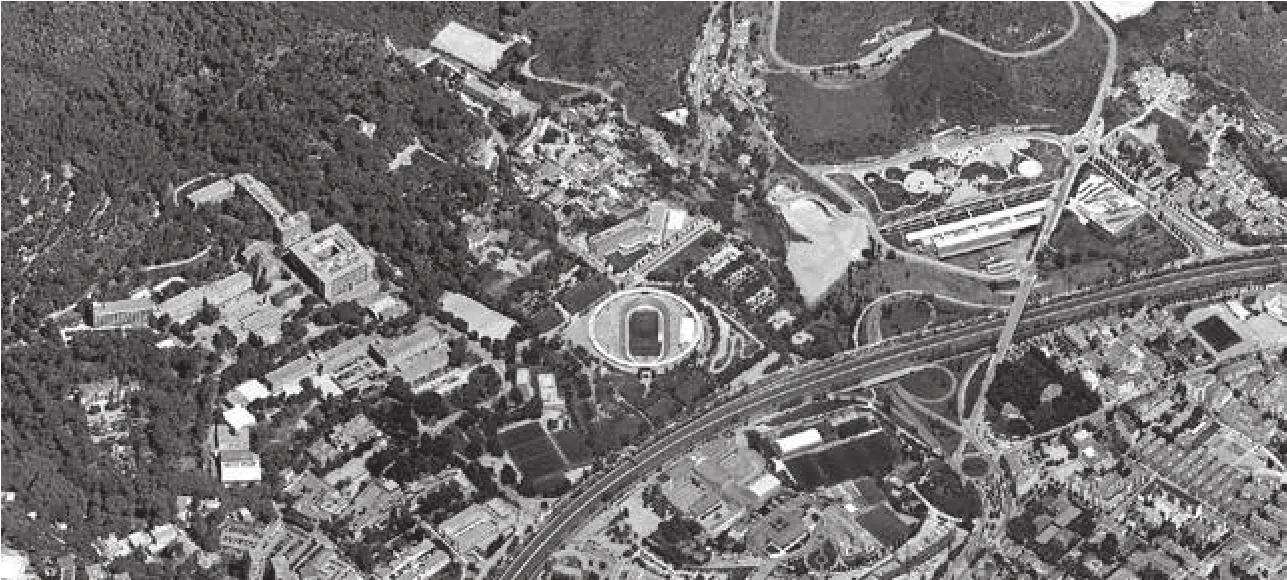

从城市地理来看,巴塞罗那坐落于近海的平原上,且被西南侧的略夫雷加特河、东北侧的贝索斯河以及东部的科索莱拉海岸山脉围合,城市的最高点位于蒂维达沃山顶 (海拔512 米)(图1)。

一直以来巴塞罗那的城市地理制约着城市空间的扩张,尤其是绵延的海岸线城市带,连通港口与腹地的交通轴线,而后是现代的塞尔达城市格网城市规划。本文将首先阐述当今都市化空间怎样超越城市地理条件,从而影响巴塞罗那的都市区规划。

新城市文化

通过城市物质空间的干预,我们将发现都市区规划中关键的切入点和策略。

图1:巴塞罗那地理情况说明, 由海、山和两条河流构成。突出三角洲, 主要的道路轴线和老城区。Fig.1:Barcelona’s interpretation of its geographical situation, framed by the sea, the mountains and the two rivers.Highlighting the delta,main road axis and historical settlements.

当下的大都市维度:新的机遇空间

二十世纪八九十年代的巴塞罗那提出城市重建和中心城区步行街区规划,这为今后的都市发展奠定了基础。紧接着,为了在两条河流之间建设紧凑化的城市, 依然延续了塞尔达城市扩张规划的网格。由于外环交通的现实性更是强化了 这种网格规划的延续性和永恒性。

巴塞罗那都市区下辖诸多地方行政部门,通过对公共空间和公园规划的发展,我 们认为这些地方行政部门的职能空间更加宽 松,相比中心城区的管理机构。这得益于当 地市政的需求,并具有一定的地方自治能力。

而今,大都市区更多受到全球化影响,随着金融和信息技术的高速运行,将会造成城市体的失衡。因为,我们认为,全球化正在以一种标准化模式强迫着城市体发展趋同;但是,每一座城市具有不同的历史、规划传统、管理方式,在全球化模式影响下,都市区规划将导致另一种结果。

城市规划与设计急需回应当前新的城市规划模式要求。都市区是开放和相互关联的, 传统的城市规模太小缺乏灵活性 , 因此我们必 须构建大都市使其具备起码的城市竞争力。

那么问题是,未来的城市规划依旧解决紧凑型城市的非生产性土地的转型问题?还是在都市区空间寻找更多的机遇? 或许,我们能通过一些城市结构手段同时解答上述问题。

我们发现, 城市的发展并不一定要像 过去几十年那样依赖物质化的增长;相 反地,开放式发展方式是确保高质量的整 合社会结构。

当今的大都市不仅为市民提供不再固化的空间,更是具有吸引力、宜人的、高效减压的、轻松自由的空间。这些城市空间具有创造性,他们可以是没有实际属性的,或者无法定义的空间,但是我们可以从此探索新的机会,(诸如以下巴塞罗那城市发展的案例)。

一、滨水区——大都市的衍生品

从“里贝拉河岸策略”到“奥林匹克滨海区”

尊重相互城市功能独立的前提下提出基础设施建设与城市发展规划的整合策略

图2:在奥运村, 我们可以看到, 城市系统的设计和干预过程比之前的阶段更为复杂, 但这确保了这些系统的发展和各种城市动机的参与。在这种情况下, 几位国际获奖建筑师被邀请参与总体规划中的不同的建筑和空间的开发。Fig.2:In the Olympic Village we can see that the process of design and intervention in urban systems is more complex than in previous periods, but this ensures the possible development of these systems and the involvement of the various urban agents.In this case, several prize winner architects were invited to develop different buildings and spaces of the overall proposal.

近几十年来, 基础设施发展的规模扩大, 导致城市运营的尺度(城市功能层级)也相应增加,其关键点是如何处理基础设施建设与城市发展之间尺度控制与相对独立的城市功能关系。

现实情况是,基础设施项目的规模总是比城市项目干预的规模要大。然而,城市项目的尺度不同于它的规模。

举例说明,巴塞罗那滨海城市带最初是铁路设施用地,由于市政需要,在这里需要建设一个新的环城道路以及市政管道来连通城市的排水系统与贝索斯河道的水处理站。自然地,因为城市功能决定了城市项目的尺度,该基础设施项目影响了整条海岸线。另一方面,从纯粹的城市发展来讲,需要一个分散可控的发展尺度,它是符合城市开发者和当地居民的需求。当然基础设施中的道路、排水系统以及公共空间都具有优先性,而后滨海的住宅和商业地块在一个中度规模的尺度下建设,最终形成一座绵延5公里海岸的滨海城市带。

1992年,奥运会为巴塞罗那带来新的滨海区

1992年奥运会为契机,巴塞罗那城市进行了 “特别” 的城市更新项目,尤其是对城市内部的改造, 重新评估了城市空地和废弃城市空间, 新建城市(通信和卫生)基础设施,将城市内不同区块连通(图2)。

1992年巴塞罗那的城市项目更像是一种城市主体功能的修复或者复原。在城市的连续性中,建立关节性的城市空间,例如奥运村的建设以三角形基址激活更大范围的城市转型(图3)。

奥运村的建设以起独特的滨海区位置成为撬动滨海区城市空间更新的一枚楔子。

二、多元化的中心城区

既有城市的重组策略

图3:在 "之前" 和 "之后" 的图像之间, 我们可以区分城市层面的行动和策略 (排污、运输、海滨、海港等),这些是为局部或者区域的设计介入.前者往往是政府机构的任务,而后者则可以与私人组织或公司进行合作.Fig.3:Between the “before” and “after” images, we can distinguish the actions or strategies designed at city level (sewage, transport, seafront, harbor, …) and those designed for parts or districts.The former tends to be the task of government agencies, whereas the latter may be carried out in cooperation with a private organization or corporation.

城市的进化改变了通信和生产系统,产生了更多空白空间。城市空间再利用得到极大的发展机遇。他们将被定位于一种宏观的策略而不是某种特殊的措施。

图4:当前道路系统 (红色) 过去的道路系统(黑色), 龙达环路主要在头等级道路系统上进行建设,要求对概念的重新思考避免城市障碍在许多城市中出现的如此普遍。Fig.4:The current road system (in red) was completed (in black), mainly with the construction of the Ronda ring roads at the head of the road hierarchy called for a rethinking of the concept to avoid the urban barriers that are so common in many cities.

图5:对角线大道旁的“利亚”是城中心最具代表的项目之一。它激活了一个城市中心被遗弃的地块,营造出一个新的“中心”。Fig.5:“L’Illa” as key example of an area of centrality along the Diagonal avenue.It recycled an abandoned site in the middle of the city.Mixed-use created a new “center”for the nearby communities.

完成紧凑化城市:再建虚空间

尽管恢复公共空间的策略十分重要,促进城市重组经济结构, 创造新发展的要求也很重要。

城市重组战略优先考虑工业和商业活动,包括基础设施和公共交通:不利于中心城区和塞尔达扩展区规划的个体的交通活动是城市内最主要的运营负荷(图4)。

因此,中心城区的重组一定是通过交通联系来重建或者间隙空间。

首先,地铁线路的扩张、地面轨道交通的建造、公交线路网有效建设创造了社区之间的通达性。其次,城市外环的建成,虽然它作为最高级的城市快速道路系统,但是我们希望避免城市交通路线 生硬切割和隔离。因此,我们通过交通系统的等级化特征,划分我们城市社区的出入口,这是一种常用的城市空间设计原理。

它可以提高公共交通和私人驾驶的可达性, 从而强化城市陈旧、闲置空间活力的可能,例如工业、港口和铁路设施等地区。另外,新的中心城区提出建立公私合作的方式来 确保大部分投资能用于基础设施工程。

这正是巴塞罗那推出的“新中心区”策略。曾经被废弃的工业和未使用的基础设施占用的13处城市空地将被引入城市活动。每一次的城市干预设计都具有规划纲要,并将经济活动融入了服务业、兴建城市设施和公园,他们都将服务于当地居民区。

一个重要的案例就是坐落于对角线大道大道旁的“利亚”(图5)。它修复了城市中间地区一处被遗弃的地块,采取了综合城市功能策略,将商场、公共服务、酒店和商务办公区整合,另外提供了一处公园、两所学校以及其他城市配套设施。当以上这些城市功能汇集到一起,也就在周边的数座社区之间创造出一个新的“中心”(图6)。

三、老城的转型

塞尔达的扩展规划和都市庭院

重回塞尔达扩展规划:从无人所知晓的社区到今天成功的邻里空间范式(图7)。

对塞尔达扩展规划的研究始于 1983年, 当时将此区域定位为类似于美国城市中心的更新模式 , 其本质是将城中心的庭院综合利用和重新分类,从而为城市街区提供祥和的绿色公共空间。

在过去的40多年里塞尔达扩展规划建设形成于巴塞罗那的老城墙和城市外围的村庄之间地带。规划师塞尔达在他自己的城市设计理论中阐述了网格原理(其雏形源于古典希腊、罗马时代), 发表在他1859年的著作《城市建设理论》中, 其中他调查了很多城市(如波士顿、都灵、圣彼得堡和布宜诺斯艾利斯等)以及各种城市要素,注入历史发展、气候和地理等特征。塞尔达在他的家乡巴塞罗那还调研了工人阶级所处的非人性化、不健康的生活居住环境。在塞尔达规划的扩展区仙柏莱设计中找不到一处工厂。在满足社会和经济需要的规划设计后,他的希冀是创造一个健康生活的“全新的、伟大的” 城市。

塞尔达街区庭院是城中之“城”

塞尔达选择了沿着外廓布置U 形三边围合, 而以一个不连续的低层建筑设置在第四条边来满足社会服务或公共用途, 意在围合内部 “庭院”, 却又可保留从公共区域的自由进出。

城市的发展导致了工业设施在塞尔达扩展规划中的建设,再加上大部分土地的私有化 特征,导致了后期大部分街区庭院被侵占。

不同的建筑法规默认了这部分内院空间的被侵占行为。然而, 人们认为 , 城市是遵循外部街道以及家庭内部活动的结果,他是居住和生产活动的相互联系(图8)。

图8:这种城市形态的丰富性在于用途的叠加和类型的多样性, 这在城市的临街面得到了严格的表达,并且在城市街区庭院内获得了巨大的自由空间。Fig.8:The richness of this urban form lies in the superposition of uses and the typological diversity, which is rigorously expressed in the urban frontage and the great freedom within the city block.

塞尔达扩展规划的住宅再启动项目开始于1980年代。在1985年,城市规划法则明确街区庭院应该是属于公共活动区域, 规划当局倡导能收回一些庭院作为公共空间, 并遵循原来的塞尔达扩展区规划的均质化分割的逻辑。而后,新的规划法则明确提出将扩展区中心街区的内庭院收回并开放成为公共花园和绿色空间(图9)。

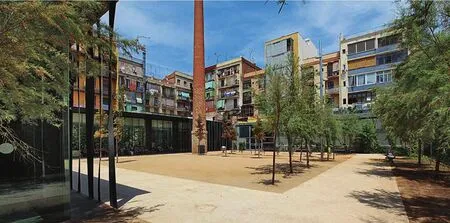

图9:圣安东尼图书馆以及内部庭院作为开放空间由2017年普利斯特奖得主RCR设计.在塞尔达的仙柏莱街区项目提议中,这个项目点是众多存有争议的案例之一,现在它终于获得了对于1985年规划提议的感谢和认可.Fig.9:The Sant Antoni library and courtyard as open space designed by the 2017 Pritzker prize winners RCR architects.An example of those controversial elements proposed by Cerdà in his Eixample project which are now being reclaimed thanks to the 1985 plan.

四、老城区的改造

巴塞罗那的老城区

老城区是城市的起源地 , 某种意义上,近代塞尔达扩展规划延缓了老城区规划改造(图10)。直至20世纪80年代老城区才开始内部改造, 这也是当时城市最鼓舞人心的城市项目。至今很少有人意识到这个项目所涉及的空前巨大的城市改建范围,还有极具复杂的项目投资和管理工作。今天,老城区与众不同的城市形态吸引了城市居民和世界游客的往来, 这里发生的一切活动都是全体市民所关注的话题。众所皆知,它向我们印证了城市空间是随着社会发展进程不断变化的过程。

老城区,历史之城

回顾这座历史名城, 就会发现它的城市遗存是多么的丰富和层次清晰: 古老的城墙, 周围的市镇, 市集形成的街道……宗教或民用建筑, 以及梧桐蔓延的兰布拉林荫大道。

另外, 历史城市和建筑空间的联合创新,例如蒙特卡达街道上的斯托达·诺瓦新型的市镇别墅、费兰和公主商业街道、新的纪念性广场如圣豪梅和皇家广场,还有随后20世纪初期较大尺度的城市转型,如莱耶塔纳大街,铁路建设和其他方面。

老城区的当代价值

老城区在当代的价值依然存在于他的建筑和城市空间。一方面,由于现实的复杂和矛盾,对城市公共或者集体空间的类型化研究将促进理解城市形态的内在价值。我们提出的批判性见解 来自于统计或者空间的分析;另一方面,城 市环境和纪念性空间不仅仅突出了丰富的艺 术纪念物程度,它作为历史中的一员持续断巩 固着城市的客观、抽象的文化尺度。

从这一角度来看 , 老城区过去二十年的城市复兴过程是文化本质的延续,至此巴塞罗那老城进入最佳发展期和成熟期(图11)。

五、新的都市区之路

绿色廊道重构巴塞罗那都市区

巴塞罗那的转型:公共空间为先导

城市设计项目将延伸到不同核心的邻里区域,建造数座城市广场和社区花园,这是城市设计项目的主要策略 ; 对集体生活空间的分享和讨论将重新回到城市的规划设计中。

废弃的工业老区转型成为城市公园(如克洛特区 , 贝伽索 区 , 西班牙工业区),它们是公共空间重 建的标志。巴塞罗那城市周边仅有少数几座公园 , 因此 , 在都市区内增加绿色空间的易达性成为一种 新需求。

这种现象被多数都市的中心城区模仿, 成为雄心 勃勃的城市复兴战略(图12)。微自然、绿色空间理念在都市区中三十多座下辖区内迅速扩张。

与自然环境更好地融合

自然化的城市的街道、广场和公园将通过 都市区的自然公园甚至农田相连,组成一个新 的开放的自然空间网络,充满生态潜力, 涵盖休 闲和生产的可能性。自然环境和文明社会的网 络都可以构成都市区的骨干(图13)。

都市区的开放空间系统必须同时具有自然生态和城市景观功能 , 并且必须建立在所有的尺度 上: 从大都市区到每一个构成它的所属地区 ; 从 市民的活动尺度到任何有助于生物多样性的微观 尺度。

环境的基质是由山川、河流、溪水、沙滩以及农 田等叠加而成,这些环境要素能在公共空间的体系上创造出不同的城市肌理,最终形成都市空间各个 组成部分。

物种间复杂的联系组成了都市区的基质。丰富、多样化的都市绿色基础设施具有自身特殊的管 理体系和模式。由于环境、社会和经济可持续性的 需求,新的都市区模式将被重新定义 :它将是保障 生物多样性、维护生态活动进程 , 最有效的生态系 统。

都市区规划中理解的绿色基础设施,是维护和促进使用或者建设多元的生态和社会生产,以及使之成为可能的实现多样的生态、景观和经济过程。

图12:长期来看大型绿地和公园具备生态承载条件,既有提供安静空间能力,又具备生态、文化和经济活力。城市的去工业化背景下,工业用地转型为城市公园。Fig.12: The green-belt and large parks provide capacity for resilience with a view to long-term adaptation to change and, in this way, achieve ecological, cultural and economic viability.The deindustrialization of cities offers new opportunities for transforming industrial land into urban parks.

图13:绿色廊道策略将增加景观基础设施的易达性和连通性,从而取代传统基础设施的生硬空间,例如高速公路、城市干道和铁路通常割裂城市空间形成城市屏障。新的绿色廊道将有助于建成的步行和自行车道。Fig.13: The green corridor strategy aims to increase accessibility and connectivity using the infrastructure of the landscape to replace heavy infrastructures such as roads, motorways and railway lines which used to act as barriers, breaking the city into pieces.The new green corridor will be very useful for structuring the landscape devoted to pedestrians and cyclists.

General framework

Barcelona can be considered as the prototype of a Mediterranean European city with a long urban tradition.With its over two thousand years of history, has played the role of capital of Catalonia.Cities in the south of Europe have quite specific formal characteristics and processes of historical formation: the density and compactness of their urban form and their evolution by means of extension rather than remodeling.

In 2012, Barcelona city had 1,620,943 inhabitants living in 98.21 square kilometers, and its metropolitan area had a population of 3.2 million in 636 square kilometers.Almost half the population of Catalonia lives in this area, which represents just 1.98% of the territory.

Barcelona is situated on a plain that slopes gently down towards the sea, delimited by the rivers Llobregat and Besòs and the coastal mountain range of Collserola, with its highest point of Tibidabo (512 meters)(Fig.1).

The plain is a space of confluence for the inland prelittoral corridor that runs in a northsouth direction, and the coastline marks out a geographical system that has governed communication axes and modern urban expansion.As this article explains, today’s metropolitan space has overflowed this natural space and its everyday influence exceeds the limits of the province of Barcelona.

Strategies for dealing with the new urban culture

If we look at the spatial and physical components which are capable of channeling the different forms of intervention, we discover key themes and potential planning strategies.To these we could apply recent experiences of projects or research in which we have been involved.

The metropolitan dimension today: new spaces of opportunity

The restructuring of the eighties and nineties and the creation of areas of centrality paved the way, then, for completing a compact city between the rivers, where the fundamental structure was still the wide-ranging force of the Eixample grid, which offered itself as a continual, constant support, reinforced by the presence of outer ring roads for traffic.

In the metropolitan municipalities, we observe processes of redevelopment based on public spaces and parks that are generally larger than those in the central city, as they have more space.However, the matrix of intervention is municipal, many of the interventions being fairly autonomous.

Today, metropolises are subject to the pressures of phenomena derived from globalization that make financial and information systems move much faster than they used to,therefore affecting and unbalancing cities in very short periods of time.We tend to think that globalization is a standardizing force that makes all metropolises the same; however,this tendency has been found to produce very different results depending on the history and urban planning tradition of each city and its forms of governance.

It is not hard to see that we are facing new urban planning paradigms that call for new responses in city strategy and design.Today the metropolis is open and its parts are mutually related; the traditional city is too small and not sufficiently flexible, and we therefore have to structure the metropolis to make it minimally competitive.

The question arises today as to whether future strategies lie in the hard transformation of unproductive spaces in the compact city, or whether we have to see spaces of opportunity principally in the metropolitan space, perhaps woven together by other structures.

Because now we are discovering that development does not necessarily call for major physical growth, as it has done in previous decades; conversely, it is important to ensure the improved integration of social structure by means of what is known as inclusive development.

The interest of a metropolis today lies in being attractive and providing pleasant,efficient spaces for the people who live and work there, as well as offering areas with less pressure or control than the stabilized areas,because it is in these places that innovative interventions, different to traditional or existing initiatives, can be carried out.It will be in these “between” spaces or rather undefined situations that we find spaces of opportunity for certain types of new developments.

1.Waterfront as spin-off for the Metropolis

From the “Ribera Counter-Plan” to the“Olympic Waterfront”

Strategies that incorporate infrastructures and development while respecting their independence

The growing size of infrastructural developments in recent decades was taken imply a corresponding increase in the dimension of urban operations.The key is to accept the relative independence of the appropriate dimensions for infrastructural and urban developments.

Infrastructure projects have always been on a larger scale than other urban interventions, and this is still the case.However, the urban dimension of a project is not the same as its size.

As an example, we take the transformation of Barcelona’s waterfront using land formerly occupied by railway infrastructure.Among other things, the design had to accommodate a new beltway and facilities to connect the city’s drainage system to the Besòs sewage plant.This project naturally affected the coastline as a whole, because that was the dimension implied by its functions.A purely urban development, on the other hand, would call for a more fragmented di-mension, in accordance with the needs of the developers and the demands of the residents.The whole infrastructure of roads, sewerage and open space had to be provided first,whereas the seafront housing and commercial development was implemented in a series of operations at an intermediate scale, progressing to form five kilometers of coastal city.

Barcelona.The new “waterfront” in the Barcelona’s Olympic ’92 project

The “special” projects of the Olympic program for Barcelona 1992 were a bet for an internal development of the existing city,either through the valorization of empty or abandoned interstitial spaces, or of the construction of urban infrastructures - of communication and sanitation- necessary to link the different districts or sectors of the city(Fig.2).

The 1992 Olympic program was proposed as a great urban reconversion project for the city.Within the urban continuum,seeking the articulation of empty interstitial areas, or provoking elements of rupture -like the triangle of the Olympic Village itself- that trigger a process of greater scope(Fig.3).

The Olympic Village becomes a qualified reference for the process of urban transformation for Barcelona, due to its position as a wedge of progress towards the “waterfront”of the city.

2.Multiple urban centralities

ANC–Areas of New Centrality.New Downtowns

Strategies to restructure the existing city

The evolution of cities produces changes in systems of communication and production,leaving empty spaces.These offer exciting opportunities for ambitious strategies of re- uses.As far as possible, they should be addressed as general strategies rather than specific operations.

Completing the compact city: restructuring empty spaces

While the strategy chosen to recover public space is fundamental, the city also needs to restructure the economy and create thresholds for new developments.

This meant that strategies for industrial and commercial activity were a priority, along with infrastructure and public transport: the city was laboring under the pressure of individual mobility that was detrimental to the central city and the Eixample(Fig.4).

In this context, it was considered vital to start work on restructuring means of transport to enhance the interstitial spaces.

Firstly, the extension of the Metro, the recovery of the tram and the rationalization of bus routes served to create links between the different communities.Then, the construction of the Ronda ring roads at the head of the road hierarchy called for a rethinking of the concept to avoid the urban barriers that are so common in many cities.A clear division between through traffic on a separate level and urban traffic, with access to the city and subject to the requirements of each urban sector,was introduced as the criterion for general design.

This increase in accessibility by public transport and private mobility served to enhance the city’s obsolete or empty spaces that had been deactivated, such as industrial,port and railway areas.A special program of new centralities served to establish mechanisms of public-private collaboration, ensuring that a large part of the capital gains generated were invested in general infrastructures pending construction.

This was the case in Barcelona and the strategy to promote “new centralities” in its urban area.Thirteen areas of wasteland,occupied by obsolete industry or unused infrastructure, provided an opportunity to introduce central activities into areas that would otherwise remained peripheral in character.Each intervention had a specific brief, and economic activity was joined by services, facilities and parks that could benefit the existing residential sectors.

One key example among the selected areas was “L’Illa” along the Diagonal avenue(Fig.5).It recycled an abandoned site in the middle of the city.Mixed-use program with shops, services, hotel and offices complemented a park, two schools and other facilities.All together created a new “center”for the nearby communities(Fig.6).

图6:新商业区策略计划重塑城市的闲置空间Fig.6:The New Downtowns strategy plan to re-structure the empty spaces of the city.

3.Transforming the downtown

Eixample Cerdà and the courtyards

The recovery of the Eixample: Today a celebrated neighborhood, at that time little known to residents.Enhancing a “great project” of the city(Fig.7)

图7:塞尔达的 仙柏莱街区项目的力量在于将一个普通的城市几乎无限延伸地穿过空巴塞罗那平原, 为一切提供了空间。Fig.7:The force of Cerdà's Eixample project lay in the idea of a regular city extending almost infinitely across the empty Barcelona Plain, where there was room for everything.

Research into the qualities of the Eixample started in 1983 in view of the transformation that was turning it into a US downtown,a central office monoculture, addressed its intrinsic values and the possibilities of conversion with mixed uses and a reclassification of the courtyards at the center of the city blocks as quiet, green spaces.

The Eixample was realized during a period just exceeding forty years on a disused terrain between the old, walled town of Barcelona and the surrounding villages.Cerdà elaborated the grid principle (originally conceived of in classical Greco-Roman times) in his own theory of urban design, published in his book “Teoría de la construcción de las ciudades /Theory of City Construction” (1859), in which he investigated numerous aspects of cities, such as the historical development and climatological and geological characteristics of such cities as Boston, Turin, St Petersburg and Buenos Aires.In his home town of Barcelona, Cerdà studied the inhumane and unhealthy living conditions of the working class.No modern factories are to be found in Cerdà’s design for the Eixample; his ambition was to create a “new and great” city, without impediments to a healthy life, and it was for this reason that the expansion plans took explicit account of both economic and social needs.

The interior courtyards are “cities” inside the city

Cerdà opted for a U-shaped layout of the building following the perimeter of the block,with a discontinuous and low construction on one side–for services or public use–with the intention of outlining the interior “courtyard”but retaining access from the public space.

The development of the project addressed industrial use in the Eixample and the intention to maximize private land management, questions that led to the occupation of the majority of the courtyards in the blocks.

Different building regulations consolidated these options and fixed the volumes that were allowed in each moment of their application.In conclusion, one can say that the city has developed following the street and a more domestic interior world that is related to residential uses and productive activity(Fig.8).

The residential recovery of the Eixample has continued apace since the eighties.In 1985, plans were set in train to reclaim some of the courtyards as public spaces,continuing the logic of a homogeneous distribution, but also considering blocks where it was more feasible for this to be done.Moreover, it restricted building in the very center of the blocks, making it possible to develop gardens and green areas in their courtyards(Fig.9).

4.Retrofitting the Old Town of Barcelona

Barcelona’s Old Town

Ciutat Vella is a seminal space in the formation of the city, where improvement work had been postponed due to the success of the Eixample(Fig.10).The internal remodeling of Ciutat Vella, started in the 1980s, has been one of the city government’s most ambitious projects, alongside the Olympic Games.Few people are aware of the huge and quite unprecedented scope of investment and management involved.Today, Ciutat Vella has a different profile; it attracts city residents and tourists alike, which is becoming an issue of concern for local residents.As we know, the city is a process of constant transformation and a social process that requires constant and careful monitoring.

图10:资本家建造了仙柏莱城市扩展的居住区,也是创新型的城市投资区;中产阶层和工人阶级在扩展区的格网规划中都有一席之地。老城成为当时卫生条件欠缺的旧城区。直至20世纪80年代,由于奥运会契机才成为当时市政府最富雄心的城市改造项目。Fig10:The bourgeois found in the Eixample the place of its residence and its most innovative investments; the middle classes followed their lead and even the working classes had their space in the Eixample grid.Ciutat Vella became a rather residual place, reaching levels with no regard for hygienist logic.Till 1980s, when it became one of the city government’s most ambitious refurbish projects, alongside the Olympic Games.

Ciutat Vella, the city throughout history

A look at the long-term construction of the historic city shows just how rich and gradual its materialization has been: town walls,surrounding boroughs, streets organized by trades, religious or civil buildings with great spatial presence, the continuous adjustment of the Rambla, and so on.

We also see how the historic city incorporated innovation, coinciding with the appearance of new forms of residence, such as the town houses in Carrer Montcada, like the Strada Nuova, and new kinds of commercial streets such as Ferran and Princesa, new calls for monumental plazas like Sant Jaume and Plaça Reial,and later and perhaps less careful large-scale transformations in the context of the twentieth century, such as Via Laietana, the construction of the Metro, and many others.

The contemporary values of Ciutat Vella

We can understand the current values of Ciutat Vella by studying its buildings and urban spaces.The classifying effort of the types and the public and / or collective spaces allows us to understand the intrinsic values of urban forms, the reading to which often escapes because its complexity and controversy.Probably an effort to objectify values,even statistical or spatial, is essential to enrich our critical knowledge and helps taking the best decisions.On the other hand, progress in representing these environmental and monumental variables allows us to understand not only the richness of the artistic monuments, but also the historical ones, and in this process, to consolidate the objective and transcendental dimensions of this singular urban legacy.

In this perspective, the rehabilitation process of the last twenty years can be seen as the resumption of an essential activity from which the best development and maturation time for the Ciutat Vella is opened(Fig.11).

5.New Metropolitan approach

Area Metropolitan of Barcelona, Green Corridors to restructure the Metropolis.

The transformation of Barcelona: public space as a priority

An extensive program of constructing squares and gardens was centered on strategic places, at the heart of different neighborhoods;collective life returned to the forefront and careful spatial design was shared and discussed in the city:a paradigm changed in city construction.

The transformation of abandoned industrial installations (El Clot, Pegaso, España Industrial) into urban parks was an important sign of change.Barcelona is a city of few parks that tend to be situated around its edges, so accessibility to green space became an attraction and a new demand.

This phenomenon driving the central city was replicated in most of the metropolitan municipalities, becoming a more ambitious strategy(Fig.12).The idea of a miniature central city in thirty or so metropolitan municipalities spread fast.

图11:长期的历史城区建设呈现了丰富和多层的物质空间形态,就像记载城市历史的古老的羊皮纸:呈现着城市类型化的描述和片段;城市历史形态学的体系,以及最近150年以来城市转型的叠加。Fig.11: The long-term construction of the historic city shows just how rich and gradual its materialization has been, like a great urban palimpsest.Typological description and fragment; morphological systems throughout history, and superposition of transformations in the last 150 years.

Creating better integration with the NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

The streets, squares and parks of our cities can re-naturalize themselves and connect with metropolitan parks as well as with the agricultural and natural areas that still remain.A new network of open spaces that will have all possible connectivities and be full of ecological potential, possibilities for leisure and productive capacities.An environmental and social network constituting one of the backbones of the metropolis(Fig.13).

The system of open spaces in the metropolis must, simultaneously, have ecological and landscape functionality, and must be built on all scales: from the metropolitan to the urban scale of each one of the cities that comprise it; from the human scale of its citizens to the microscopic scale of anything that may contribute to the enhancement of biodiversity.

It is the intentional superimposition of the environmental matrix formed by mountains, rivers, streams, beaches and agricultural spaces on the systems of public spaces that can be created within the different urban fabrics that make up the metropolis.

The complex relationships between species make up the territorial matrix.There is a rich and varied green metropolitan infrastructure with its own specific management bodies and models.A new metropolitan paradigm towards environmental, social and economic sustainability needs to be defined which ensures biodiversity and the maintenance of ecological processes, maximizes ecosystem services and regulates any disturbance.

Green infrastructures in the metropolis can only be explained from the maintenance and promotion of the different ecological and social flows that use or build them, as well as from the different ecological, landscape and economic processes that make them possible.