Ranges of Understanding:On the Vast Scope of Art Interpretation.A Wittgensteinian Perspective

2018-06-17StefanMajetschak

Stefan Majetschak

Abstract: The article examines the question ofwhat“understanding an artwork” means and offers some considerations about the ranges of understanding that we experience in interpretations of art: the vast scope between the contrasting extremes“expert knowledge” on the one hand and “artblindness” on the other.With respect to the philosophy of later LudwigWittgenstein itwill be shown what these ranges originate from and why they are unavoidable.Thismay come as a surprise to some philosophers since Wittgenstein usually is not regarded as someone from whom onemight expect pronouncements of an aesthetic nature.But in fact Wittgenstein had spent much time considering questions of art and art theory.Indeed in 1949 he even noted that besides“conceptual” questions only“aesthetic questions” could “really grip” him(CV 2006: 91e).However, he never formulated his reflections on questions of aesthetics in an extended and coherent series of remarks.Rather his observations in this regard are to be found in individual remarks scattered in considerable quantity throughout the papers of his Nachlass.In the paper at hand a certain number of them has been reconstructed systematically.

Keywords: artworks; ranges of understanding; art blindness; expert knowledge

It is a somewhat trivial observation thatworks of art, in particular works of visual art, about which I will speak in the first instance,exhibit semantic ranges in which they might be understood.In various epochs and in different cultures the same art object is often apprehended in quite different ways.In borderline cases,itmay happen within the same epoch and culture that what appears to some as an art work worthy of aesthetic admiration is regarded by others as an objectnot to be taken seriously,as is crystal clear from the interminable debates still being conducted about works of art such as Marcel Duchamp's“Fountain” of1917.Buteven ifwe take the example of a Picasso painting,whose ontological status as an “artwork” is scarcely in dispute, it is clear that what people see and understand can be extremely varied.For its understanding can clearly range from well-informed expert knowledge to irredeemably ignorant art blindness.

In the following remarks Iwish to examine the question of what“understanding art works” really means and to say a little of the ranges of understanding between the contrasting extremes“expert knowledge” on the one hand and “art blindness” on the other.In this regard, Iwould like to offer an explanation ofwhat these ranges originate from and why they are unavoidable.Iwill do this—which may perhaps come as a surprise to some readers—with respect to considerations of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein,who is generally regarded as an analytical philosopher of language,but not as someone from whom one might expect pronouncements of an aesthetic nature.But in fact Wittgenstein had spent his whole life considering questions of art and art theory.Indeed in 1949 he even noted that besides“conceptual” questions only“aesthetic questions” could “really grip” him(CV 2006: 91e).However, he never formulated his reflections on questions of aesthetics in an extended and coherent series of remarks.Rather his observations in this regard are to be found in individual remarks scattered in considerable quantity throughout the papers of his Nachlass,which we have to reconstruct.

Although I will make use of his thoughts primarily to explain the concept of“understanding”with respect to works of the visual arts,his own examples usually come from music,the art form most immediately familiar to him.Music is thus principally what he refers to when he thinks about what“understanding” of an artwork means.In a long remark made in 1948 with the title“Understanding&Explaining a musical phrase”(CV 2006: 79e), he was therefore concerned to point outwith respect tomusic thatwhatwe call the“understanding” of an artwork is neither something like a mental process that accompanies its external perception nor a“specific experiential content” (CV 2006:80e)which we gain from perceiving it.Wittgenstein knows, of course, that we are often tempted to explain the understanding of art in this way.But whatever may happen internally in a person who perceives an art work:these mental processes and contents within a person at least cannot be what causes us to attribute or deny to someone artistic judgement,since usually we know nothing at all about them when we do so.And this shows that criteria other than internal processes or contents must govern our utterances when we talk about somebody's“understanding” of art: criteria like perceivable phenomena of expression in a person's behaviour,his or her acting or speaking and so on.For, to remain with this example,

[a]ppreciation of music is expressed in a certain way,both in the course of hearing&playing and at other times too.This expression sometimes includes movements,but sometimes only the way the one who understands plays, or hums,occasionally too paralles he draws&images which, as it were, illustrate the music.Someone who understands music will listen differently(with a different facial expression, e.g.), play differently,hum differently,talk differently about the piece than someone who does not understand.(CV 2006:80e)

Das Verständnis der Musik hat einen gewissen Ausdruck, sowohl während des Hörens und Spielens, als auch zu andern Zeiten.Zu diesem Ausdruck gehören manchmal Bewegungen,manchmal aber nur, wie der Verstehende das Stück spielt,oder summt, auch hie&da Vergleiche,die er zieht, &Vorstellungen, die die Musik gleichsam illustrieren.Wer Musik versteht,wird anders(mit anderem Gesichtsausdruck, z.B.)zuhören, anders spielen, anders summen, andersüber das Stück reden, als der es nicht versteht.(CV 2006:80)

In particular,experts who demonstrate their understanding not only behave in theway described,but also speak in a certain way,and so consideration of what is really said by them in aesthetic explanations may be helpful when it comes to specifying precisely what ismeant by understanding music or understanding art in general.

So,what is really being said in aesthetic explanations of experts?In his Cambridge lectures on aesthetics from 1938Wittgenstein made an important observation in this regard:he pointed out that experts, when they “ make an aesthetic judgement about a thing, [...] do not just gape at it and say: ‘Oh, how marvellous!’” (L&V 1966:6).Rather they usually make much more complex statements.“A person who has a judgement” in aesthetic matters, therefore, “doesn’ t mean a person who says‘Marvellous’ at certain things”(ibid.).On the contrary, “it is remarkable”,Wittgenstein emphazised, “that adjectives such as‘beautiful’, ‘fine’” or‘marvellous’ “play hardly any role” (V&L 1966: 3)when talking about arts knowledgeably. “Words such as ‘lovely’”,‘marvellous’ oder‘beautiful’, according to Wittgenstein's shrewd observation, mostly“are first used as interjections”, particularly by“people[...] who can’ t express themselves properly”(ibid.)with respect to arts because they lack the ability to make a differentiated and appropriate judgement about an art work.The expert,on the other hand,is someone able to make competent judgements inmatters of art—and it is precisely in this field thatwe“distinguish between a person who knows what he is talking about and a person who doesn’t” (L&V 1966: 6).He does not simply say‘marvellous’ or‘lovely’, but rather gives reasons for his aesthetic judgements by talking in a certain way.

An expert will justify his aesthetic judgement that a particular art work is original, inspiring,interesting or whatever else, for example, by pointing out how the work of art in question can or should be looked at.Thismeans:he will emphasize aspects of the art work respectively the art work's internal structure that deserve particular consideration, and so on.And for this reason,according to Wittgenstein, in “conversations on aestheticmatters” use is frequentlymade of“words”such as:

“‘You have to see it like this, this is how it ismeant’; ‘When you see it like this, you see where it goeswrong’; ‘You have to hear these bars as an introduction”; “You must listen out for this key’; ‘You must phrase it like this’”

“‘Du musst es so sehen, so ist es gemeint’;, Wenn Du es so siehst, siehst Du, wo der Fehler liegt’; ‘Du musst diese Takte als Einleitung hören’;, Du musst nach dieser Tonart hinhören’; ‘Du musst es so phrasieren’”

and so on.Bymeans of formulations like these the expert draws attention to the possibility of noticing a particular aspect in an art work,in the light of which its structure or contentmight become intelligible to the listener or observer.Therefore one can-as Joachim Schulte has already emphasized-say in a certain respect that‘understanding an artwork’means forWittgenstein“something like seeing a new aspect of an object”, which changes our previous understanding of the artwork in question.When we notice a certain aspect,i.e.the fact that something can be seen or heard as something,we thus do not only see differently,but also see the work quite different,i.e.in a way in which we did not perceive it before.

This noticing of aspects—the seeing or perceiving of something as something—was examined elaborately byWittgenstein in hisMS 144,themanuscript that served as the basis of what was formerly known as Part 2 of Philosophical Investigations.When he addresses the issue of‘seeing as’ here, he does not refer explicitly to art examples, butwhen he asks himself elsewhere:“how do we arrive at the concept‘seeing this as that’ at all?On what occassions does it get formed,when is there need of it?” He answers:“Very frequently in art” (Z 1967: 208).The fact that in music a sequence of tones can be heard as an introduction,in a poem a verse can be perceived as amelody or in a painting a figure can be seen as a portrait of the donor:“Those are the things that are often noticed by experts”, as Schulte rightly comments.

In MS 144Wittgenstein discussed what he calls“noticing an aspect” (PI 2009: 203)or the“lighting up” (PI 2009: 204)of an aspect, as already stated,not using examples of art but by means of a series of simple figures,including a drawing from Joseph Jastrow's Fact and Fable in Psychology(1901),which can be seen as the head of a duck or a rabbit.It achieved a certain celebrity under the name“the duck-rabbit”(ibid.).But even in this trivial example it is possible to illustrate what the expert does when explaining that certain aspects can be noticed in works of art.

To be clear about what it means to notice an aspect in this duck-rabbit drawing, it is, according toWittgenstein, “useful to introduce the concept of a picture-object”(PI 2009: 204)into the discussion and to differentiate between it and the pictorial inscription at hand.The picture-object is what a viewer sees in a pictorial inscription and normally, that is, in the case of images whose type of representation is familiar to us,the identification of the picture-object is in no way variable in interpretation and aspect-related but clear-cut.

So,with regard to what is visible to us, for example, in the greyscale proportions of black and white photography, we do not say:‘I see this as Ludwig Wittgenstein.’Rather we say: ‘I see Wittgenstein’ or‘I see Wittgenstein on the photograph.’The clear-cut nature of the identification thus depends not somuch on the objective qualities of the inscription confronting us butmore on whether we are familiar with the representational type of the image,for example a particular style of painting or,in this case,the photographic greyscale proportions and whether we know how to read them.AsWittgenstein asks:

“‘Could Isay whata picturemustbe like to produce this effect[i.e.a clearcut identification of the picture-object/S.M.]?No.There are, for example, styles of painting which do not convey anything to me in this immediate way,but do to other people.I think that custom and upbringing have a hand in this.”(PI 2009:211)

“Könnte ich sagen, wie ein Bild beschaffen sein muss, um dies[ sc.Eindeutigkeit der Identifikation/S.M.]zu bewirken?Nein.Es gibt Malweisen,die mir nichts in dieser unmittelbaren Weise mitteilen,aber doch andern Menschen.Ich glaube,dass Gewohnheit und Erziehung hier mitzureden haben.(PI 2009:211)

The painting styles that we have learned and see applied, for example, also in the duck-rabbit,are indeed not“arbitrary” for us, in the sense of being randomly exchangeable,for we cannot simply“choose one at pleasure[...] (The Egyptian, for instance.)” (PI 2009: 241).But, depending on custom and upbringing,they are conventional.For even in the case of images that use representational styles that we regard as quite“naturalistic”, e.g.photographs,we can still imagine that they say nothing to people who have grown up and live in another cultural context and allow them no clear-cut identification of the picture-object they are looking at.“[W]e view the photograph, the picture on our wall, as the very object(the man, landscape, and so on)represented in it” (PI 2009: 216).However,this

“need not have been so.We could easily imagine people who did not have this attitude to such pictures.Who,for example,would be repelled by photographs,because a face without colour,and even perhaps a face reduced in scale, struck them as inhuman.”(ibid.)

“müsste nicht sein.Wir können uns leicht Menschen vorstellen,die zu diesen Bildern nicht dies Verhältnis hätten.Menschen z.B.,die von Photographien abgestoßen würden, weil ihnen ein Gesicht ohne Farbe,ja vielleicht ein Gesicht in verkleinertem Maßstab,unmenschlich vorkäme.” (PI2009: 216)

Nevertheless,we will never say when looking at a photograph:“I see or interpret this as Wittgenstein.” Instead, we say:“Isee Wittgenstein.”

In the case of the duck-rabbit the situation is the exact opposite:in this simple figure a painting style familiar to us,that is the convention of representing a form by means of outlines,is used in such a way that the inscription can be read multiaspectually and, to this extent, two different pictureobjects can be identified.One might say that this,in a certain sense,is the point of this primitive image.Of the one who fails to see this and accordingly only sees a“picture-rabbit” (PI 2009:204),it will probably be said that he does not understand the image because he fails to see an aspect that can be noticed.And so one will perhaps try to help him to understand by saying things such as, “Youmust see the image as a duck” or perhaps“You must see the left side of the image as a duck's beak.Then you'll understand it.”One will thus draw attention to the noticeable aspects.This may draw the viewer's attention to the possible aspect change that has been created in the image and enable him to see that the inscription permits multiple readings.When this is the case,he understands the inscription differently,and perhaps he will say, “Now Isee it as a duck” or express his new understanding bymeans of a formulation such as“That is a tilting image that can be seen as a rabbit and as a duck.”

In the case of the duck-rabbit,noticing the different aspects can be called “understanding” and pointing to them by means of sentences like“You have to see this as that” “explaining” the picture.And perhaps to the surprise ofmany,this thoroughly can be compared to what is called understanding and explaining in fine arts.Indeed,inasmuch as Wittgenstein's observation that the concept“seeing this as that”has its rightful place in an art context is correct, one can probably even say that, using the duck-rabbit as an example, we have, as it were,played through what it means to“understand and explain”a work of art.For precisely in art contexts an expert will usually try to make aspects of an art work noticeable with his explanations,pointing out how something in the art work can be seen as something.And in this way he will try to open up“understanding”.

To relate this claim more closely to the practice ofmaking aesthetic judgements,let us take as an example Picasso's Le Rêve(The Dream)painted in 1932.The painting uses the late Cubist style that we,accustomed to the many different styles of representation that have developed in the course of about 150 years of western modern art,are not likely to reject as unintelligible or disfigured.Rather,it allows us to clearly identify the picture-object of the image.We see a woman sitting in an armchair,head to one side, dreaming, from which the painting gets its name.And there are viewers who perceive nothing other than this in the painting.However,one can become aware of the fact that Picasso,when painting the face of the woman,also made use of the phenomenon of“shape change or aspect change”which we know from the duck-rabbit drawing.When an expert, in this case an art historian, points this out to us, we notice perhaps all of a sudden:“The dreaming eye of the woman can be seen not only as an eye, butalso as the sexual organ of aman.” The interpretation of the expert emphasizes this aspect and, thanks to the explanation, we will possibly understand the painting in a different way.We will then, like the expert, perhaps say that Picasso's multi-aspectual fusion of eye and male sexual organ in the pictorial arrangement of the face of the dreaming woman goes plausibly“beyond the apparently unconnected,joins together the heterogeneous and thereby provocatively makes something visible, that is unique, that has never been seen like this before”.But whatever we then say: If we notice here the possible aspect, we will probably understand the painting in a different way and are likely to interpret it differently,for example with regard to the question of what the woman is dreaming.

Both the duck-rabbit and Picasso's painting are examples that seem to confirm the remark of Joachim Schulte cited earlier that understanding an artwork is something like seeing a new aspect of the object at hand.For,to the extent that the inscriptions in both casesmight from the start have been created in order to generate amultiplicity of readings,these readings can be regarded as based on properties of the inscriptions as such.And so it is not implausible to speak of“understanding” as noticing an aspect of the art work itself.But unfortunately,the matter is much more complicated in many,probably most works of art.When we point to an aspectwith regard to its visual or auditive presence and say, “You have to hear this sequence of tones as an introduction” or“You must see this figure as a variation of an old iconographic motif”and thereby open up new ranges of understanding and interpretation,we do not refer to an objective property of the object itself.Rather,one has to realize, as Wittgenstein puts it, that“ what I perceive in the lighting up of an aspect is not a property of the object,but an internal relation between it and other objects” (PI 2009: 223).

Strictly speaking,whatWittgenstein emphasizes in this passage is also true in the case of the duckrabbit and of Picasso's painting.When we notice that the duck-rabbit, among other things, can be seen as a duck or the upper half of the woman's face in Picasso's painting as a male sexual organ,we perceive an internal relation between the pictureobject and other objects familiar to us from other contexts.It strikes us,and this draws our attention to something new that is not, like a property,already founded in the picture-object itself.The same is true,with reference to Wittgenstein's favourite repertoire of examples,of noticing an aspect in music,e.g.when we learn to understand a sequence of tones as an ecclesiastical mode of church music.

“To understand an ecclesiastical mode doesn’t mean to get used to a sequence of tones[...].It means,rather, to hear something new, something that I haven’t heard before, say like—indeed quite analogously to—suddenly being able to see 10 lines,which earlier Iwas only able to see as 2 times 5 lines,as a characteristic whole.” (BT 2013: 442 [322])

“Eine Kirchentonart verstehen, heißt nicht, sich an die Tonfolge gewöhnen[...].Sondern es heißt, etwas Neues hören, was ich früher noch nicht gehört habe,etwa in der Art— ja ganz analog—, wie eswäre, 10 Striche, die ich früher nur als 2 mal 5 Striche habe sehen können, plötzlich als ein charakteristisches Ganzes sehen zu können.” (BT 2013: 442 [322])

It is, of course, right that different inscriptions in painting and drawing or different tone sequences in music motivate aspect perception in varying degrees.Therefore,one would have to distinguish between images such as the duck-rabbit and Picasso's painting,which are both created from the outset to allow several aspects to emerge and art workswhich correlate to other objects in an internal relation only because the interpreter places the work into an appropriate,but hitherto unconsidered context of comparison.But Wittgenstein was not interested in this difference.His concern was the basic insight that no audible or visible sequence of inscriptions in a certain medium(words in a poem,brush strokes in painting,tones in music or whatever),compels us to notice an internal relation between it and something elsemerely because of its objective properties.Rather,that some internal relation between an art work and other objects becomes audible or visible always depends on the contextualizations with which we surround the given signs.Wittgenstein shows this using quite simple examples:

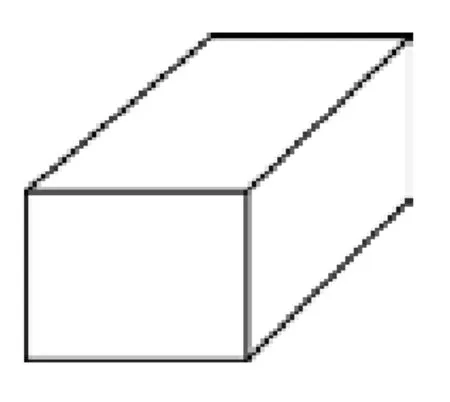

One could imagine the illustration

appearing in several places in a book,a textbook for instance.In the accompanying text,something different is in question every time:here a glass cube, there an upturned open box, there a wire frame of that shape,there three boards forming a solid angle.Each time the text supplies the interpretation of the illustration.(PI 2009:203)

Man könnte sich denken,dass an mehreren Stellen eines Buches,z.B.eine Lehrbuches,die Illustration

stünde.Im dazugehörigen Text ist jedesmal von etwas anderem die Rede:Einmal von einem Glaswürfel, einmal von einer umgestülpten offenen Kiste, einmal von einem Drahtgestell,das diese Form hat, einmal von drei Brettern, die ein Raumeck bilden.Der Text deutet jedesmal die Illustration.(PI 2009:203)

According to the context, we can “see the illustration now as one thing, now as another” (PI 2009: 203).Very often these contextualizations,asWittgenstein says, may simply be“fictions”.He demonstrates this once again by means of a simple sign.

And what is true of this simple sign is,of course,particularly true of artworkswith their often complex internal structure,which can motivate a large number of contextualizations.

Precisely for this reason,with regard to works of art those vast scopes of understanding open up.Theymove between the extremes of expert knowledge on the one hand and art blindness on the other.The one who is blind to art—and Iwill return to this soon— is the one who,when looking at an art work,is unable to see any internal relation between the object and other objects because no appropriate contextualization occurs to him.He is able to see,for example,in Duchamp's Fountain nothing more than an object of everyday use.By contrast,individuals we call experts are able,by means of appropriate contextualizations,to allow internal relations between the work at hand and other objects to emerge and so to make aspects visible in the light ofwhich the work can be understood.With regard to art works such contextualizations,as Wittgenstein saw, will often be‘fictions’, which require on the part of the expert“imagination” (PI 2009:218),for they must occur to him as appropriate contextualizations that make aspects accessible and thus open up understanding.This does, of course,notmean that the contexts that we allow to occur to us and in which a work of art can be acceptably placed can be invented totally at random.On the contrary,it belongs to the skills required for an expert in aesthetic judgements that he is able to plausibly anchor an art work in the context of our culture-specific art forms and art historical traditions.

The expertwho does this will then undoubtedly offer us, in order to make a work intelligible,“certain comparisons-grouping together of certain cases” (L&V 1966: 29).In Wittgenstein's opinion such comparisons arewhat“we reallywant” in order“to solve aesthetic puzzles” (ibid.)presented to us by many works.Thus, the expert will say, as we have seen in the example of Picasso's painting,something like, “You have to see this as that”, and so on.Or, he will“sometimes find the similarity between the style of a musician and the style of a poet who lived at the same time, or a painter”(L&V 1966:32)since— asWittgenstein put it in 1948— “teaching” someone“to appreciate poetry or painting can be part of an explanation of what music is” (CV 2006: 81e).In any case he will try to create,by means of offering a suitable contextualization,a new internal relation between the inner structure of the work and that what the work in his opinion refers to or expresses.

“Take Brahms and Keller”, Wittgenstein is supposed to have said in his 1938 lectures:

I often found that certain themes of Brahms were extremely Kellerian.This was extraordinarily striking[…]If I say this theme of Brahms is extremely Kellerian,the interest this has is first that these two lived at the same time.Also that you can say the same sortof things on both of them—the culture of the time in which they lived.If I say this,this comes to an objective interest.The interest might be that my words suggest a hidden connection.(L&V 1966: 32)

This“hidden connection” might not have been noticed before.Only by grouping the two in thisway an internal relation becomes evident which sheds new light on both.Thus like in a“surveyable representation” — Wittgenstein's primary means of presenting material in philosophy—a specific grouping of the facts“points to a secret law” (GB 1979:8)within a realm of philosophical problems,a particular comparison between art forms or specific artworks of a time can help making visible hitherto unnoticed internal relations.

More important than reflecting on the means,however,thatmight serve to open up internal relations are the philosophical consequences connected with his insights.Because everything that the expert will say is ultimately bound up with his being able to surround the work with the appropriate“fiction”,aesthetic explanations, according to Wittgenstein,are based fundamentally on nothing else than acceptance.This means: “ You have to give the explanation that is accepted.This is the whole point of the explanation” (L&V 1966: 18).Since the aspect to which it points is not an objective property of the object,it is impossible to prove its correctness bymeans of criteria that we normally use to justify empirical statements.That iswhy he towhom Ioffer such an aesthetic explanation,for instance with regard to a passage in a piece ofmusic,does

not have to accept the explanation;it is not after all as though I had given him compelling reasons for comparing this passage with this&that.In did not e.g.explain to him that remarks made by the composer show that this passage is supposed to represent this&that.(CV 2006:79e)

musste er ja die Erklärung nicht annehmen; es ist ja nicht, als hätte ich ihm sozusagen überzeugende Gründe dafür gegeben,dass diese Stelle vergleichbar ist dem&dem.Ich erkläre ihm ja, z.B.,nicht ausÄußerungen des Komponisten,diese Stelle habe das&das darzustellen.(CV 2006:79)

Of course,it is true that certain patterns of explanation,certain ways of enveloping works of art with ‘fictions’ are more convincing at certain times than at others.“At a given time the attraction of a certain kind of explanation is greater than you can conceive” (L&V 1966: 24).When Wittgenstein held his lectures about aesthetics at the end of the 1930s,psychoanalytical patterns of explanation were extraordinarily common,and he discusses them critically and in detail in his lectures.Intertextual and interpictorial patterns of explanation,which see texts and images become visible in other texts and images,clearly appeal to art study and criticism today.But whether this or any other type of explanation makes the work understandable for anyone is in principle an open question.

And itmust remain an open question since,as Wittgenstein asks, couldn’t“there be human beings lacking the ability to see something as something—and what what would that be like?” (PI 2009:224).The term he uses of this“defect” is“aspect-blindness” (ibid.).People being aspectblind would principally be unable to understand an explanation encouraging them to see something as something.Probably nobody has this defect in a fullscale radical form.But,if one accepts Wittgenstein's suggestion that“[a]spect-blindness will be akin to the lack of a‘musical ear’” (PI 2009:225)and analogously regards art blindness as a less dangerous kind of aspect-blindness,one has to admit that art blindness as the inability to imagine an internal relation between the artwork and other objects is really quite common among people and, where this defect is present, at least every form of aesthetic explanation is doomed to failure.

Notes

①The writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein are cited here using the uniform citation keys,which can be found in the Bibliographie der deutsch-und englischsprachigen Wittgenstein-Ausgaben/Bibliography of German and English Editions of Wittgenstein(published in Wittgenstein-Studien 02/2011,249-286),compiled by Alois Pichler and Michael Biggs.This bibliography can also be downloaded as a PDF file at www.ilwg.eu.

②The case in which we maintain of ourselves that we understand a work of artmay, for the sake of simplicity, be excluded here.When we say:“Now Iunderstand themusic!”(or the poem, the picture etc), we identify our understanding of course not with the help of criteria of any sort.

③ Three students, Rush Rhees, Yorick Smithies and James Taylor,attended these lectures and took notes which have been published as Lectures and Conversations on Aethetics,Psychology and Religious Belief.Edited by Cyril Barrett,Oxford:Basil Blackwell1966(cited as L&C 1966).

④ MS 144,i.e.the formerly so-called second part of the Philosophical Investigations,is included in PI2009 under the title Philosophie der Psychologie—Ein Fragment/Philosophy of Psychology—A Fragment and cited hereinafter with the page number of PI2009.The passage quoted above is from PI 2009:213.

⑤ Joachim Schulte, “Ästhetisch richtig“, in: Joachim Schulte, Chor und Gesetz.Wittgenstein im Kontext,Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp 1990,84.My translation.

⑥See note 5.

⑦ In German:“H-E-Kopf” (PI2009: 204).

⑧ In German:“Bildgegenstand” (PI 2009: 204).

⑨ Axel Müller, “Syntax ohne Worte.Das Kunstwerk als Beziehungsform “, in: Klaus Sachs-Hombach/Klaus Rehkämper(Hrsg.), Bildgrammatik.Interdisziplinäre Forschungen zur Syntax bildlicher Darstellungsformen,Magdeburg: Scriptum 1999,236.My translation.

⑩In the passage cited the German text uses the word“Vorstellungskraft” (PI 2009: 218).In what follows Wittgenstein also mentions“Phantasie” (PI 2009: 224),which in the English version is also translated as‘imagination’.

[11] For a more detailed interpretation of Wittgenstein's comparison between the music of Johannes Brahms and the writing of Gottfried Keller see Joachim Schulte, “WhatMakes Brahms Kellerian?”, in: Stefan Majetschak, Anja Weiberg(Eds.),Aestheticts Today.Contemporary Approaches to the Aesthetis of Nature and of Art, Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter 2017.

[12] See on this pointmore detailed Stefan Majetschak, Survey and Surveyability.Remarks on two central notions in Wittgenstein's later philosophy, in: Wittgenstein-Studien 07(2016).

Works Cited

Barrett, Cyril, ed.Lectures and Conversations on Aethetics,Psychology and Religious Belief.Ed.Cyril Barrett.Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1966(cited as L&C 1966).

Majetschak,Stefan.“Survey and Surveyability.Remarks on two central notions in Wittgenstein's later philosophy.”in: Wittgenstein-Studien 7(2016):65- 80.

Müller, Axel.“Syntax ohne Worte.Das Kunstwerk als Beziehungsform.” in: Klaus Sachs-Hombach/Klaus Rehkämper(Hrsg.), Bildgrammatik.Interdisziplinäre Forschungen zur Syntax bildlicher Darstellungsformen.Magdeburg:Scriptum 1999.

Pichler, Alois, and Michael Biggs, eds.Bibliographie der deutsch-und englischsprachigen Wittgenstein-Ausgaben/Bibliography of German and English Editions of Wittgenstein.In: Wittgenstein-Studien 2(2011):249-86.

Schulte, Joachim. “ Ästhetisch richtig.” in: Joachim Schulte:Chor und Gesetz.Wittgenstein im Kontext.Frankfurt/Main:Suhrkamp 1990.

---.“What Makes Brahms Kellerian?.” in: Aestheticts Today:Contemporary Approaches to the Aesthetis of Nature and of Art.Eds.Stefan Majetschak and Anja Weiberg.Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2017.