鸟类弓形虫基因型研究进展

2018-03-13,,,,,,2

, ,,,,,2

刚地弓形虫(Toxoplasmagondii)是地域分布广、宿主多、生活史复杂、危害大的一种重要人兽共患寄生虫。据估计全世界约有1/3的人感染弓形虫[1]。鸟类、啮齿类、哺乳类,甚至海洋动物皆可作为弓形虫的宿主[2]。人体弓形虫感染主要有3种途径:摄入含有包囊的生的或未熟肉类;食入被卵囊污染的食物或饮水;以及经胎盘的垂直传播。由于感染率之高,刚地弓形虫在欧美被列为继沙门菌(Salmonella)和李斯特菌(Listeria)之后的第三大致死性食源性疾病的病原体[3]。一个多世纪以来,研究人员对弓形虫的研究热情始终不减,一是因为弓形虫引起的家养动物(如羊、猪、牛、鸡等)的疾病和流产导致重大的经济损失,严重影响制约畜牧养殖业的发展;二是感染动物成为人兽共患病的感染来源,危害公共卫生安全;三是免疫力低下人群(HIV/AIDS患者、恶性肿瘤长期化疗患者等)的隐性感染可激活为急性活动性感染并引发脑炎、肺炎和眼病等严重疾病,可导致患者死亡;孕期感染弓形虫可致不良妊娠结局或新生儿先天性弓形虫病;四是弓形虫生活史需要转换宿主,各生活史阶段的虫体形态不同,为研究寄生物与宿主/细胞之间的相互作用提供了良好模型[4]。

随着弓形虫的基因组测序的完成,以及人兽分离株的逐渐增多,已发现各地区的人兽分离虫株存在种内遗传结构(基因型)差异。目前为止,弓形虫数据库中已经报告并记录的基因型有232个(http://toxodb.org/toxo)。分型所用方法多采用多位点 PCR-RFLP,遗传标志从早年的1-6个,到目前[SAG1,(5′+3′)SAG2,SAG3,BTUB,GRA6,c22-8,c29-2,L358,PK1和Apico]10个位点。针对于国内外的研究者用于虫体分离的宿主标本多包括野生动物(高原鼠兔和野鼠)、流浪猫、家兔、家猪、市售猪肉、宠物犬以及人体等,鸟类的弓形虫株基因型报道总体相对较少。自2003年起,Dubey等针对于分布于全球不同国家和地区的散养家鸡的流行情况、基因型进行一些研究报道。人工养殖的鸡、鸭、鹅、鸽子以及鹌鹑、鸵鸟、宠物鸟等有少量报道。近年来,Su等对黑雁(Brantacanadensis)、疣鼻天鹅(Cygnusolor)等有迁徙习性珍稀候鸟极少报道。在中文文献数据库中尚未对于鸟类弓形虫基因型的综述文献,本文针对目前报道的家养禽类、观赏鸟类,以及自然野生珍稀鸟类的弓形虫株基因型做简要概述,为鸟类弓形虫株种群结构信息提供参考。

1 家养禽类弓形虫株基因型

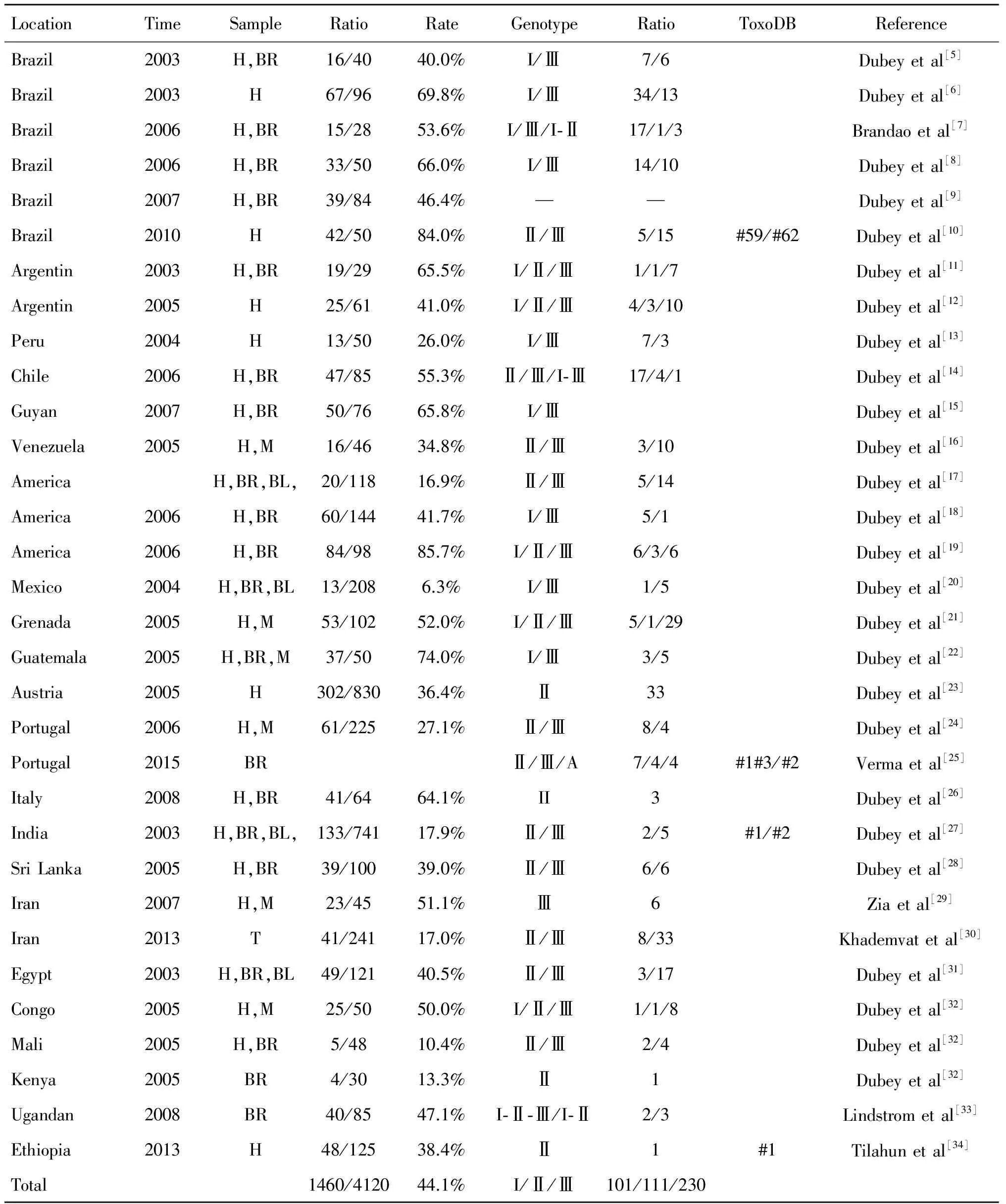

目前,针对于散养家鸡的报道相对于其他鸟类较多。自2003年起,Dubey等开始对散养家鸡(Gallusdomesticus)弓形虫的流行情况、遗传基因进行研究,样本来源于巴西、美国、墨西哥、葡萄牙、印度、伊朗、刚果、马里等分布于世界南美洲、北美洲、欧洲、亚洲、非洲五大洲的国家和地区。来自全球的22个国家散养家鸡的弓形虫流行情况,文中报道的检测方法大多运用Dubey建立的改良凝集试验(MAT),通过采集鸡大脑、心脏和血液等组织和成分,进行抗体水平测定。本文所收集总的报道有4120个样本,其中总的阳性样本为1460个,平均阳性感染率44.1%。其中,按照区域来分,五个大洲的平均阳性感染率依次为南美洲(54.0%)、北美洲(46.1%)、欧洲(42.5%)、非洲(33.3%)、亚洲(31.3%)。针对于全球五个大洲散养家鸡的弓形虫感染阳性率比较分析可以看出,美洲、欧洲地区相对偏高,非洲、亚洲相对偏低。综合分析可能有以下原因:一是欧美国家和地区生活人口的饮食习惯和生活方式不同,人的弓形虫感染率高于亚非地区;二是欧美国家和地区由于研究鸟类弓形虫起步较早,研究的范围、发表论文和报道数据要多于亚非国家和地区。总体而言,散养家鸡的弓形虫感染率相对较高,平均约为50%,特别是在一些农村卫生条件差,散养家禽和猫等多种动物混养的地区更高。弓形虫是一种土源性、食源性寄生虫,猫为其终末宿主,散养在空旷土地上的家鸡因为猫的活动、土壤啄食、混合饮水等途径感染,严重危害公共卫生安全,须引起高度重视。此外,值得一提的是,本文中所参考的文献,对于鸟类弓形虫研究,在采集样本时多选取鸟类的脑、心脏、血液等组织和成分,因弓形虫在这几个组织和成分相对富集,获取虫体的概率相对较高。

全球南美洲、北美洲、欧洲、亚洲、非洲五个大洲报道的关于散养家鸡的弓形虫感染基因型多为常见经典的Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型和Ⅲ型,来自全球的22个国家和地区,除欧洲、亚洲地区没有出现Ⅰ型弓形虫外,当地散养家鸡弓形虫感染均存在Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型和Ⅲ型,其中南美洲的巴西、智利分别出现Ⅰ-Ⅱ型、Ⅰ-Ⅲ型弓形虫混合基因型,非洲的乌干达同时出现Ⅰ-Ⅱ-Ⅲ和Ⅰ-Ⅱ型弓形虫混合基因型,欧洲的葡萄牙报道出现独特的基因型模式弓形虫感染(ToxoDB:#254)。混合基因型和非典型基因型不计入内,从Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型和Ⅲ型占比情况来看,南美洲Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型和Ⅲ型数量为84、29、77,Ⅰ型、Ⅲ型可能为优势基因型。北美洲Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型和Ⅲ型数量为16、9、64,Ⅲ型远超其他基因型。欧洲没有报道Ⅰ型,Ⅱ型、Ⅲ型数量为51、8,Ⅱ型的数量远远多于Ⅲ型。亚洲、非洲地区Ⅲ型的数量居多。从全球五大洲的数量综合来看,Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型、Ⅲ型分别为101、111、230,Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型持平,Ⅲ型约为Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型的两倍,Ⅲ型可能为全球散养家鸡感染弓形虫的优势基因型(表1)。

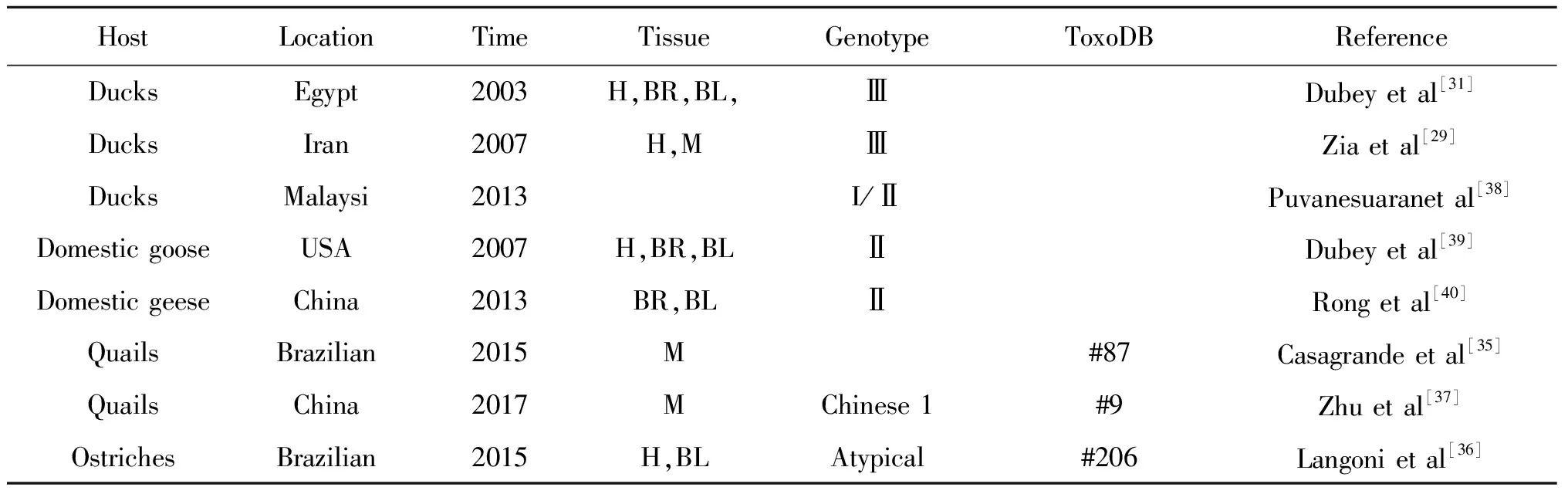

目前,除散养家鸡外,人工养殖的禽类主要有散养家鸭、家鹅、鹌鹑、鸵鸟等,对于禽类的报道非常少,对于来自埃及、伊朗、马来西亚、美国、中国五个国家报道的散养家鸭、家鹅主要的弓形虫基因型为Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型、Ⅲ型。Casagrande等[35]报道在巴西农场养殖的鹌鹑的弓形虫基因型为#87。Langoni等[36]发现屠宰场的鸵鸟基因型为#206,与一个先前报道引起巴西患者先天性弓形虫病(tgosbr1,ToxoDB#206)的基因型一致,支持了鸵鸟为弓形虫污染环境的哨兵。Zhu等[37]报道中国常见的鹌鹑感染弓形虫的基因型为Toxo#9,与中国哺乳动物、啮齿类动物感染的主要优势基因型Chinese 1,即Toxo#9一致,为监测和控制鹌鹑的弓形虫的感染情况提供依据(表2)。

表1 全球分布散养家鸡的弓形虫病流行情况和基因型概况

Tab.1 Prevalence and genotype of toxoplasmosis in free-range chickens (Gallus domesticus) distributed around the world

LocationTimeSampleRatioRateGenotypeRatioToxoDBReferenceBrazil2003H,BR16/4040.0%I/Ⅲ7/6Dubeyetal[5]Brazil2003H67/9669.8%I/Ⅲ34/13Dubeyetal[6]Brazil2006H,BR15/2853.6%I/Ⅲ/I⁃Ⅱ17/1/3Brandaoetal[7]Brazil2006H,BR33/5066.0%I/Ⅲ14/10Dubeyetal[8]Brazil2007H,BR39/8446.4%——Dubeyetal[9]Brazil2010H42/5084.0%Ⅱ/Ⅲ5/15#59/#62Dubeyetal[10]Argentin2003H,BR19/2965.5%I/Ⅱ/Ⅲ1/1/7Dubeyetal[11]Argentin2005H25/6141.0%I/Ⅱ/Ⅲ4/3/10Dubeyetal[12]Peru2004H13/5026.0%I/Ⅲ7/3Dubeyetal[13]Chile2006H,BR47/8555.3%Ⅱ/Ⅲ/I⁃Ⅲ17/4/1Dubeyetal[14]Guyan2007H,BR50/7665.8%I/ⅢDubeyetal[15]Venezuela2005H,M16/4634.8%Ⅱ/Ⅲ3/10Dubeyetal[16]AmericaH,BR,BL,20/11816.9%Ⅱ/Ⅲ5/14Dubeyetal[17]America2006H,BR60/14441.7%I/Ⅲ5/1Dubeyetal[18]America2006H,BR84/9885.7%I/Ⅱ/Ⅲ6/3/6Dubeyetal[19]Mexico2004H,BR,BL13/2086.3%I/Ⅲ1/5Dubeyetal[20]Grenada2005H,M53/10252.0%I/Ⅱ/Ⅲ5/1/29Dubeyetal[21]Guatemala2005H,BR,M37/5074.0%I/Ⅲ3/5Dubeyetal[22]Austria2005H302/83036.4%Ⅱ33Dubeyetal[23]Portugal2006H,M61/22527.1%Ⅱ/Ⅲ8/4Dubeyetal[24]Portugal2015BRⅡ/Ⅲ/A7/4/4#1#3/#2Vermaetal[25]Italy2008H,BR41/6464.1%II3Dubeyetal[26]India2003H,BR,BL,133/74117.9%Ⅱ/Ⅲ2/5#1/#2Dubeyetal[27]SriLanka2005H,BR39/10039.0%Ⅱ/Ⅲ6/6Dubeyetal[28]Iran2007H,M23/4551.1%Ⅲ6Ziaetal[29]Iran2013T41/24117.0%Ⅱ/Ⅲ8/33Khademvatetal[30]Egypt2003H,BR,BL49/12140.5%Ⅱ/Ⅲ3/17Dubeyetal[31]Congo2005H,M25/5050.0%I/Ⅱ/Ⅲ1/1/8Dubeyetal[32]Mali2005H,BR5/4810.4%Ⅱ/Ⅲ2/4Dubeyetal[32]Kenya2005BR4/3013.3%Ⅱ1Dubeyetal[32]Ugandan2008BR40/8547.1%I⁃Ⅱ⁃Ⅲ/I⁃Ⅱ2/3Lindstrometal[33]Ethiopia2013H48/12538.4%Ⅱ1#1Tilahunetal[34]Total1460/412044.1%I/Ⅱ/Ⅲ101/111/230

Note: H, Heat; BR, Brain; BL, Blood; M, Muscle; A, Atypical; -, Mixed genotype.

表2 主要禽类的弓形虫基因型

Tab.2 Genotype of Toxoplasma gondii in main birds

HostLocationTimeTissueGenotypeToxoDBReferenceDucksEgypt2003H,BR,BL,ⅢDubeyetal[31]DucksIran2007H,MⅢZiaetal[29]DucksMalaysi2013I/ⅡPuvanesuaranetal[38]DomesticgooseUSA2007H,BR,BLⅡDubeyetal[39]DomesticgeeseChina2013BR,BLⅡRongetal[40]QuailsBrazilian2015M#87Casagrandeetal[35]QuailsChina2017MChinese1#9Zhuetal[37]OstrichesBrazilian2015H,BLAtypical#206Langonietal[36]

Note: H, Heat; BR, Brain; BL, Blood; M, Muscle; A, Atypical.

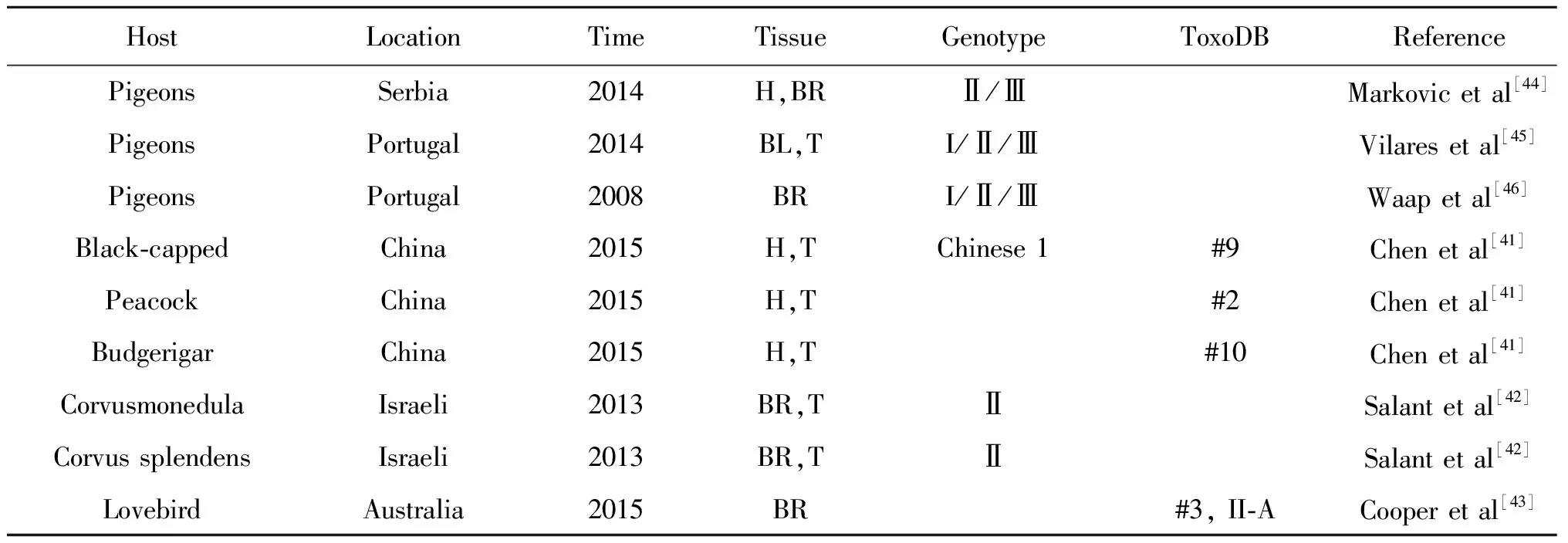

2 观赏鸟类弓形虫株基因型

鸟类是人们旅游观赏的重要宠物之一,主要的观赏鸟类有原鸽、黑盖、孔雀、鹦鹉、鸦类等。塞尔维亚、葡萄牙报道的原鸽弓形虫基因型有典型的Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型、Ⅲ型。Chen等[41]报道在中国福建野生动物园的黑盖、孔雀和虎皮鹦鹉的三种宠物鸟进行检测,其弓形虫基因型分别为ToxoDB#9、ToxoDB#2和ToxoDB#10,表明野生动物园宠物鸟存在弓形虫传播风险。Salant等[42]报道来自以色列的散养寒鸦、家鸦弓形虫基因型均为Ⅱ型,结论表明人口密度和鸦类弓形虫感染率呈现正相关。Cooper等[43]研究发现澳大利亚的牡丹鹦鹉感染弓形虫后,出现严重的神经系统症状,肉眼检查发现脑出血,脾肿大,肝炎,右心室增厚等。脑病变组织切片海绵状变化,有弥漫性、非化脓性脑炎。弓形虫基因型为非典型II型,该基因型先前澳大利亚野生动物有记录,表明弓形虫可通过环境途径传播(表3)。

表3 人工饲养观赏鸟的弓形虫基因型

Tab.3 Artificial feeding ornamental bird Toxoplasma gondii genotype

HostLocationTimeTissueGenotypeToxoDBReferencePigeonsSerbia2014H,BRⅡ/ⅢMarkovicetal[44]PigeonsPortugal2014BL,TI/Ⅱ/ⅢVilaresetal[45]PigeonsPortugal2008BRI/Ⅱ/ⅢWaapetal[46]Black⁃cappedChina2015H,TChinese1#9Chenetal[41]PeacockChina2015H,T#2Chenetal[41]BudgerigarChina2015H,T#10Chenetal[41]CorvusmonedulaIsraeli2013BR,TⅡSalantetal[42]CorvussplendensIsraeli2013BR,TⅡSalantetal[42]LovebirdAustralia2015BR#3,II⁃ACooperetal[43]

Note: H, Heat; BR, Brain; BL, Blood; M, Muscle; A, Atypical.

3 野生珍稀鸟类弓形虫株基因型

目前,全球报道的野生珍稀鸟类约20种左右,根据《世界自然保护联盟》(IUCN)濒危物种红色名录(IUCN.Org:https://www.iucn.org/)、《国家保护有益的或者有重要经济、科学研究价值的陆生野生动物名录》、《国家重点保护野生动物名录》等法律法规及其公约的相关规定,将目前报道的感染弓形虫的野生珍稀鸟类进行归类,明确其所受保护的等级,为后续的野生珍稀鸟类弓形虫基因型研究及其保护提供一定参考[47]。表4所列的自然野生珍稀鸟类,大多为重点保护野生动物,其感染弓形虫为地区散发,时有报道,发病的鸟类数量通常为个例。自然珍稀鸟类弓形虫基因型大多为典型Ⅱ型、Ⅲ型,Ⅰ型相对较少。此外,Su等[48]报道的美国夏威夷黑雁(Brantasandvicensis)被列入2012年《世界自然保护联盟》(IUCN)濒危物种红色名录“易危”(VU)的受威胁级别,发现其弓形虫基因型为ToxoDB#261、ToxoDB#262。Aubert等[49]报道的法国灰林鸮(Strixaluco)在我国为国家二级保护动物,其弓形虫基因型为Ⅱ型。Dubey等[50]报道的哥斯达黎加彩虹巨嘴鸟(Ramphastossulfuratussulfuratus),其弓形虫基因型非克隆系典型Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型,还发现Ⅲ变异型,为ToxoDB#52首次报道弓形虫从彩虹巨嘴鸟分离。Zhu等[51-53]报道的中国新疆地区的七彩山鸡(PhasianuscolchicusLinnaeus)、家麻雀(Passerdomesticus),中国兰州地区的家麻雀(Passerdomesticus)以及中国吉林地区的黄雀(Carduelisspinus)、小云雀(Alaudagulgula)的弓形虫基因型均为为Ⅱ变异型,花脸鸭(Anasformosa)为Chinese 1型,ToxoDB#9,其中黄雀、小云雀和花脸鸭均被列入列入中国国家林业局2000年8月1日发布的《国家保护有益的或者有重要经济、科学研究价值的陆生野生动物名录》(表4)。

表4 自然野生珍稀鸟类的弓形虫基因型

Tab.4 Genotype of Toxoplasma gondii in natural wild rare birds

LevelHostLocationTimeTissueGenotypeToxoDBReferenceIC⁃2013⁃LCCanadageesAmerica2004TⅢDubeyetal[54]IC⁃2012⁃LCMuteswanAmerica2013HⅢ#2#216Suetal[55]IC⁃2013⁃LC4CanadageeseAmerica2016HII/III#1#2#4#266Vermaetal[56]IC⁃2012⁃VUHawaiianGeeseAmerica2016BL,T#261#262Suetal[48]IC⁃2013⁃LCWoodpeckerAmerica2007BRⅢGerholdetal[57]IC⁃2012⁃LCWoodpeckerNorway2014BR,TⅡJokelainenetal[58]IC⁃2012⁃LCSturnusvulgarisIran2013TⅡ/ⅢKhademvatanetal[30]IC⁃2014⁃LCTawnyOwlFrance2008BRIIAubertetal[49]IC⁃2012⁃LCToucanCostaRica2008BR,BLnon⁃clonalI,#52Dubeyetal[50]GuineafowlBrazil2011BLⅡDubeyetal[59]IC⁃2012⁃LCPheasanChina2012MII⁃V#3Zhuetal[51]IC⁃2012⁃LCGallusgallusNicaraguaBLI,II,III,#52ToxoDBColumbaliviaIran2013TⅡ/ⅢKhadeetal[30]CT⁃2010⁃LCEareddovesBrazil2014BL,T#1#6#17Barrosetal[60]IC⁃2013⁃LCHouseChina2012MII⁃V#3Zhuetal[51]IC⁃2013⁃LCHouseChina2013H,BR,LUII⁃V#3Zhuetal[52]IC⁃2013⁃LCHouseIran2013TⅡ/ⅢKhadeetal[30]IC⁃2009⁃LCEurasianSiskinChina2015BRII⁃V#3Zhuetal[53]IC⁃2012⁃LCOrientalSkylarkChina2015BRII⁃V#3Zhuetal[53]IC⁃2012⁃LCAnasformosaChina2015H,LUChinese1#9Zhuetal[53]IC⁃2012⁃LCTreesparrowsChina2012MI#10Zhuetal[51]IC⁃2013⁃LCRedhawkAmerica2013BRI/Ⅱ#10/#5Suetal[61]IC⁃2013⁃LCGriffonvulturesIsraeli2013BR,TⅡSalantetal[42]

Note: H, Heat; BR, Brain; BL,: Blood; M, Muscle; LU, Lung; A, Atypical; V, Variant;

ICUNCEP-IC, World Conservation Union Catalog of endangered species; LC, 低危; VU, 易危;

CTWPSUESS-CT, Catalog of terrestrial wildlife protected by the state or useful in economic and scientific research

4 小 结

目前,关于鸟类弓形虫基因型的研究报道相对较少,鸟类作为弓形虫传播的重要的中间宿主动物群体,目前针对于鸟类弓形虫主要基因型中散养家鸡Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型、Ⅲ型均有,其中Ⅲ型居多;散养家鸭、家鹅、鹌鹑、鸵鸟等主要禽类以及原鸽、黑盖、孔雀、鹦鹉、鸦类等观赏鸟类,有典型的Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型、Ⅲ型以及chinese1型;雁雀等野生珍稀鸟类,出现典型的Ⅱ型、Ⅲ型以及Ⅱ型非典型基因型,其基因型丰富度较高。

鸟类弓形虫的研究鸡、鸭、鹅等禽类是人类动物源性食品主要来源之一,观赏饲养鹦鹉、鸽子等动物人工宠物鸟类成为人们旅游观光、休闲娱乐方式之一,鸟类弓形虫的感染率、基因型、毒力的研究对于公共卫生、食品安全、旅游行业具有重要意义。对于野生珍稀迁徙候鸟的弓形虫的基因种群结构、毒力相关因子、传播路线途径、种间遗传进化等是未来研究的热点。随着鸟类弓形虫基因型研究的不断深入和拓展,相关的种群结构等生物信息将逐步得以丰富。

[1] Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis[J]. Lancet, 2004, 363(9425): 1965-1976. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X

[2] Krusor C, Smith WA, Tinker MT, et al. Concentration and retention ofToxoplasmagondiioocysts by marine snails demonstrate a novel mechanism for transmission of terrestrial zoonotic pathogens in coastal ecosystems[J]. Environ Microbiol, 2015, 17(11): 4527-4537. DOI: 10.1111/1462-2920.12927

[3] Guo M, Dubey JP, Hill D, et al. Prevalence and risk factors forToxoplasmagondiiinfection in meat animals and meat products destined for human consumption[J]. J Food Prot, 2015, 78(2): 457-476. DOI: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-328

[4] Shen JL, Wang L. Genotypes and main effectors ofToxoplasmagondiiand their pathogenic mechanisms[J]. Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis, 2015,33(6): 429-435. (in Chinese)

沈继龙, 王林. 弓形虫的基因型及其主要效应分子的致病机制[J]. 中国寄生虫学与寄生虫病杂志, 2015,33(6):429-435.

[5] Dubey JP, Navarro IT, Graham DH, et al. Characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates from free range chickens from Parana, Brazil[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2003, 117(3): 229-234.

[6] Dubey JP, Graham DH, Da SD, et al.Toxoplasmagondiiisolates of free-ranging chickens from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: mouse mortality, genotype, and oocyst shedding by cats[J]. J Parasitol, 2003, 89(4): 851-853.

[7] Brandao GP, Ferreira AM, Melo MN, et al. Characterization ofToxoplasmagondiifrom domestic animals from Minas Gerais, Brazil[J]. Parasite, 2006, 13(2): 143-149. DOI: 10.1051/parasite/2006132143

[8] Dubey JP, Gennari SM, Labruna MB, et al. Characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates in free-range chickens from Amazon, Brazil[J]. J Parasitol, 2006, 92(1): 36-40. DOI: 10.1645/GE-655R.1

[9] Dubey JP, Sundar N, Gennari SM, et al. Biologic and genetic comparison ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates in free-range chickens from the northern Para state and the southern state Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil revealed highly diverse and distinct parasite populations[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2007, 143(2): 182-188. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.024

[10] Dubey JP, Rajendran C, Costa DG, et al. NewToxoplasmagondiigenotypes isolated from free-range chickens from the Fernando de Noronha, Brazil: unexpected findings[J]. J Parasitol, 2010, 96(4): 709-712. DOI: 10.1645/GE-2425.1

[11] Dubey JP, Venturini MC, Venturini L, et al. Isolation and genotyping ofToxoplasmagondiifrom free-ranging chickens from Argentina[J]. J Parasitol, 2003, 89(5): 1063-1064.

[12] Dubey JP, Marcet PL, Lehmann T. Characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates in free-range chickens from Argentina[J]. J Parasitol, 2005, 91(6): 1335-1339.

[13] Dubey JP, Levy MZ, Sreekumar C, et al. Tissue distribution and molecular characterization of chicken isolates ofToxoplasmagondiifrom Peru[J]. J Parasitol, 2004, 90(5): 1015-1018.

[14] Dubey JP, Patitucci AN, Su C, et al. Characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates in free-range chickens from Chile, South America[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2006, 140(1/2): 76-82. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.023

[15] Dubey JP, Applewhaite L, Sundar N, et al. Molecular and biological characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates from free-range chickens from Guyana, South America, identified several unique and common parasite genotypes[J]. Parasitology, 2007, 134(Pt11): 1559-1565. DOI: 10.1017/S0031182007003083

[16] Dubey JP, Lenhart A, Castillo CE, et al.Toxoplasmagondiiinfections in chickens from Venezuela: isolation, tissue distribution, and molecular characterization[J]. J Parasitol, 2005, 91(6): 1332-1334. DOI: 10.1645/GE-500R.1

[17] Dubey JP, Graham DH, Dahl E, et al.Toxoplasmagondiiisolates from free-ranging chickens from the United States[J]. J Parasitol, 2003, 89(5): 1060-1062. DOI: 10.1645/GE-124R

[18] Dubey JP, Su C, Oliveira J, et al. Biologic and genetic characteristics ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates in free-range chickens from Costa Rica, Central America[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2006, 139(1/3): 29-36. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.02.031

[19] Dubey JP, Sundar N, Pineda N, et al. Biologic and genetic characteristics ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates in free-range chickens from Nicaragua, Central America[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2006, 142(1/2): 47-53. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.016

[20] Dubey JP, Morales ES, Lehmann T. Isolation and genotyping ofToxoplasmagondiifrom free-ranging chickens from Mexico[J]. J Parasitol, 2004, 90(2): 411-413. DOI: 10.1645/GE-194R

[21] Dubey JR, Bhaiyat MI, de Allie C, et al. Isolation, tissue distribution, and molecular characterization ofToxoplasmagondiifrom chickens in Grenada, West Indies[J]. J Parasitol, 2005, 91(3): 557-560. DOI: 10.1645/GE-463R

[22] Dubey JP, Lopez B, Alvarez M, et al. Isolation, tissue distribution, and molecular characterization ofToxoplasmagondiifrom free-range chickens from Guatemala[J]. J Parasitol, 2005, 91(4): 955-957. DOI: 10.1645/GE-493R.1

[23] Dubey JP, Edelhofer R, Marcet P, et al. Genetic and biologic characteristics ofToxoplasmagondiiinfections in free-range chickens from Austria[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2005, 133(4): 299-306. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.06.006

[24] Dubey JP, Vianna MC, Sousa S, et al. Characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates in free-range chickens from Portugal[J]. J Parasitol, 2006, 92(1): 184-186. DOI: 10.1645/GE-652R.1

[25] Verma SK, Ajzenberg D, Rivera-Sanchez A, et al. Genetic characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates from Portugal, Austria and Israel reveals higher genetic variability within the type II lineage[J]. Parasitology, 2015, 142(7): 948-957. DOI: 10.1017/S0031182015000050

[26] Dubey JP, Huong LT, Lawson BW, et al. Seroprevalence and isolation ofToxoplasmagondiifrom free-range chickens in Ghana, Indonesia, Italy, Poland, and Vietnam[J]. J Parasitol, 2008, 94(1): 68-71. DOI: 10.1645/GE-1362.1

[27] Sreekumar C, Graham DH, Dahl E, et al. Genotyping ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates from chickens from India[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2003, 118(3/4): 187-194.

[28] Dubey JP, Rajapakse RP, Ekanayake DK, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization ofToxoplasmagondiifrom chickens from Sri Lanka[J]. J Parasitol, 2005, 91(6): 1480-1482.

[29] Zia-Ali N, Fazaeli A, Khoramizadeh M, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization ofToxoplasmagondiistrains from different hosts in Iran[J]. Parasitol Res, 2007, 101(1): 111-115. DOI: 10.1007/s00436-007-0461-7

[30] Khademvatan S, Saki J, Yousefi E, et al. Detection and genotyping ofToxoplasmagondiistrains isolated from birds in the southwest of Iran[J]. Br Poult Sci, 2013, 54(1): 76-80. DOI: 10.1080/00071668.2013.763899

[31] Dubey JP, Graham DH, Dahl E, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization ofToxoplasmagondiifrom chickens and ducks from Egypt[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2003, 114(2): 89-95.

[32] Dubey JP, Karhemere S, Dahl E, et al. First biologic and genetic characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates from chickens from Africa (Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Kenya)[J]. J Parasitol, 2005, 91(1): 69-72.

[33] Lindstrom I, Sundar N, Lindh J, et al. Isolation and genotyping ofToxoplasmagondiifrom Ugandan chickens reveals frequent multiple infections[J]. Parasitology, 2008, 135(Pt1): 39-45. DOI: 10.1017/S0031182007003654

[34] Tilahun G, Tiao N, Ferreira LR, et al. Prevalence ofToxoplasmagondiifrom free-range chickens (Gallusdomesticus) from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia[J]. J Parasitol, 2013, 99(4): 740-741. DOI: 10.1645/12-25.1

[35] Casagrande RA, Pena HF, Cabral AD, et al. Fatal systemic toxoplasmosis in Valley quail (Callipepla californica)[J]. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl, 2015, 4(2): 264-267. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2015.04.003

[36] Da SR, Langoni H. Risk factors and molecular typing ofToxoplasmagondiiisolated from ostriches (Struthio camelus) from a Brazilian slaughterhouse[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2016, 225: 73-80. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.06.001

[37] Cong W, Ju HL, Zhang XX, et al. First genetic characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiinfection in common quails (Coturnix coturnix) intended for human consumption in China[J]. Infect Genet Evol, 2017, 49: 14-16. DOI: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.12.027

[38] Puvanesuaran VR, Noordin R, Balakrishnan V. Isolation and genotyping ofToxoplasmagondiifrom free-range ducks in Malaysia[J]. Avian Dis, 2013, 57(1): 128-132. DOI: 10.1637/10304-071212-ResNote.1

[39] Dubey JP, Webb DM, Sundar N, et al. Endemic avian toxoplasmosis on a farm in Illinois: clinical disease, diagnosis, biologic and genetic characteristics ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates from chickens (Gallus domesticus), and a goose (Anser anser)[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2007, 148(3/4): 207-212. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.06.033

[40] Rong G, Zhou HL, Hou GY, et al. Seroprevalence, risk factors and genotyping ofToxoplasmagondiiin domestic geese (Anser domestica) in tropical China[J]. Parasit Vectors, 2014, 7: 459. DOI: 10.1186/s13071-014-0459-9

[41] Chen R, Lin X, Hu L, et al. Genetic characterization ofToxoplasmagondiifrom zoo wildlife and pet birds in Fujian, China[J]. Iran J Parasitol, 2015, 10(4): 663-668.

[42] Salant H, Hamburger J, King R, et al.Toxoplasmagondiiprevalence in Israeli crows and Griffon vultures[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2013, 191(1-2): 23-28. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.07.029

[43] Cooper MK, Slapeta J, Donahoe SL, et al. Toxoplasmosis in a pet peach-faced lovebird (Agapornisroseicollis)[J]. Korean J Parasitol, 2015, 53(6): 749-753. DOI: 10.3347/kjp.2015.53.6.749

[44] Markovic M, Ivovic V, Stajner T, et al. Evidence for genetic diversity ofToxoplasmagondiiin selected intermediate hosts in Serbia[J]. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis, 2014, 37(3): 173-179. DOI: 10.1016/j.cimid.2014.03.001

[45] Vilares A, Gargate MJ, Ferreira I, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiisolated from pigeons and stray cats in Lisbon, Portugal[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2014, 205(3/4): 506-511. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.08.006

[46] Waap H, Vilares A, Rebelo E, et al. Epidemiological and genetic characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiin urban pigeons from the area of Lisbon (Portugal)[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2008, 157(3/4): 306-309. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.07.017

[47] Wang ZB. Catalog of terrestrial wildlife protected by the state or useful in economic and scientific research[J]. Chin J Wildlife, 2000(5): 49-82. (in Chinese)

王志宝.国家保护的有益的或者有重要经济、科学研究价值的陆生野生动物名录[J]. 野生动物学报, 2000(5):49-82.

[48] Work TM, Verma SK, Su C, et al.Toxoplasmagondiiantibody prevalence and tow new genotypes of the parasite in endangered Hawaiian geese (BrantaSandvicansis)[J]. J Wildl Dis, 2016, 52(2): 253-257. DOI: 10.7589/2015-09-235

[49] Aubert D, Terrier ME, Dumetre A, et al. Prevalence ofToxoplasmagondiiin raptors from France[J]. J Wildl Dis, 2008, 44(1): 172-173. DOI: 10.7589/0090-3558-44.1.172

[50] Dubey JP, Velmurugan GV, Morales JA, et al. Isolation ofToxoplasmagondiifrom the keel-billed toucan (Ramphastossulfuratus) from Costa Rica[J]. J Parasitol, 2009, 95(2): 467-468. DOI: 10.1645/GE-1846.1

[51] Huang SY, Cong W, Zhou P, et al. First report of genotyping ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates from wild birds in China[J]. J Parasitol, 2012, 98(3): 681-682.

[52] Cong W, Huang SY, Zhou DH, et al. Prevalence and genetic characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiin house sparrows (Passerdomesticus) in Lanzhou, China[J]. Korean J Parasitol, 2013, 51(3): 363-367. DOI: 10.3347/kjp.2013.51.3.363

[53] Zhang FK, Wang HJ, Qin SY, et al. Molecular detection and genotypic characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiin wild waterfowls in Jilin Province, Northeastern China[J]. Parasitol Int, 2015, 64(6): 576-578. DOI: 10.1016/j.parint.2015.08.008

[54] Dubey JP, Parnell PG, Sreekumar C, et al. Biologic and molecular characteristics ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates from striped skunk (Mephitismephitis), Canada goose (Brantacanadensis), black-winged lory (Eoscyanogenia), and cats (Feliscatus)[J]. J Parasitol, 2004, 90(5): 1171-1174. DOI: 10.1645/GE-340R

[55] Dubey JP, Choudhary S, Kwok OC, et al. Isolation and genetic characterization ofToxoplasmagondiifrom mute swan (Cygnusolor) from the USA[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2013, 195(1-2): 42-46. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.12.051

[56] Verma SK, Calero-Bernal R, Cerqueira-Cezar CK, et al. Toxoplasmosis in geese and detection of two new atypicalToxoplasmagondiistrains from naturally infected Canada geese (Branta canadensis)[J]. Parasitol Res, 2016, 115(5): 1767-1772. DOI: 10.1007/s00436-016-4914-8

[57] Gerhold R W, Yabsley MJ. Toxoplasmosis in a red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus)[J]. Avian Dis, 2007, 51(4): 992-994. DOI: 10.1637/7978-040407-CASER.1

[58] Jokelainen P, Vikoren T. Acute fatal toxoplasmosis in a Great Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocopos major)[J]. J Wildl Dis, 2014, 50(1): 117-120. DOI: 10.7589/2013-03-057

[59] Dubey JP, Passos LM, Rajendran C, et al. Isolation of viableToxoplasmagondiifrom feral guinea fowl (Numida meleagris) and domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) from Brazil[J]. J Parasitol, 2011, 97(5): 842-845. DOI: 10.1645/GE-2728.1

[60] Barros LD, Taroda A, Zulpo DL, et al. Genetic characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiisolates from eared doves (Zenaida auriculata) in Brazil[J]. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet, 2014, 23(4): 443-448. DOI: 10.1590/S1984-29612014073

[61] Yu L, Shen J, Su C, et al. Genetic characterization ofToxoplasmagondiiin wildlife from Alabama, USA[J]. Parasitol Res, 2013, 112(3): 1333-1336. DOI: 10.1007/s00436-012-3187-0

[62] Dubey, JP. A review of toxoplasmosis in wild birds[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2002, 106(2): 121-153.