五氯酚对土壤跳虫代谢转化酶基因和蜕皮相关基因表达的影响

2018-01-29张倩倩乔敏

张倩倩,乔敏,*

1. 中国科学院生态环境研究中心城市与区域生态国家重点实验室,北京 100085 2. 中国科学院大学,北京 100049

五氯酚(pentachlorophenol, PCP)是一种含氯有机物,被广泛用作农药和木材防腐剂等;在我国,PCP及其钠盐常被用于杀灭血吸虫的中间宿主——钉螺,以防治血吸虫病[1]。PCP的广泛使用,引起了严重的污染问题,在水、沉积物和土壤等环境介质中以及一些生物体内都有检出[1-4]。PCP具有致癌性、免疫毒性、神经毒性、生殖毒性和内分泌干扰效应等[5-6]。目前,对PCP毒理效应的研究主要集中在大鼠、斑马鱼、大型溞等生物上[5, 7-8],对土壤无脊椎动物的研究较少。

在土壤生态毒理学的研究中,跳虫是一种常用的模式生物[9]。跳虫的存活率、繁殖和回避行为等指标,可被用于指示污染物的毒性[10-11]。Crouau等[11]研究了PCP对跳虫的繁殖毒性,在暴露时间为33~34 d时,繁殖抑制EC50为87 mg·kg-1。此外,跳虫分子水平上的指标,也越来越多地被用于生态毒理学的研究中[12-15]。与存活率、繁殖等毒性终点相比,分子水平上的指标一般更敏感,反应更快。

细胞色素P450(Cytochrome P450, CYP450)和谷胱甘肽-S-转移酶(Glutathione-S Transferase, GST)等是常用的分子生物标志物。CYP450和GST都是代谢转化酶,CYP450是一相代谢酶,GST是二相代谢酶,它们在外源物质的代谢和解毒方面起重要作用[13-14, 16-17]。 有研究报道,菲能诱导跳虫CYP450和GST基因的表达[13-14]。PCP能被人的CYP450 3A4转化为四氯对苯二酚[18];四氯对苯二酚能消耗谷胱甘肽,造成氧化损伤[19]。在PCP降解菌中,PCP被氧化为四氯对苯二酚后,会被GST转化为2,6-二氯对苯二酚,再经其他氧化还原酶作用转化为3-氧代己二酸[20]。

内分泌干扰物能影响生物的内分泌系统,从而影响生物的生长、发育和繁殖等。已有一些研究表明PCP具有内分泌干扰效应[5-6, 21-22],但少有PCP对土壤无脊椎动物内分泌干扰效应的研究。跳虫作为一种节肢动物,在其整个生命过程中持续蜕皮[23]。节肢动物的蜕皮是由激素控制的,目前对节肢动物蜕皮过程已有一些研究,发现一些蜕皮相关基因,但对跳虫蜕皮相关基因表达的研究很少,内分泌干扰物暴露下跳虫蜕皮相关基因表达变化更鲜有报道。

本文以人工土壤为暴露介质,研究了不同浓度PCP暴露下,跳虫蜕皮相关基因、CYP450和GST基因表达水平的变化,以期为PCP等内分泌干扰物的生态毒性和生态风险评价提供科学依据。

1 材料与方法(Materials and methods)

1.1 实验材料

供试生物为白符跳(Folsomiacandida),来自挪威国家农业与环境研究所(Bioforsk),在本实验室持续培养。培养方法如下:跳虫饲养于培养皿中,底部有0.5 cm厚的培养基,培养基由熟石膏、活性炭和蒸馏水(质量比为9:1:7)混合后制成。培养皿放在人工气候箱(宁波江南RXZ-380D)中,控制温度为(20±1) ℃,湿度为(70%±5%),黑暗培养。每周补充蒸馏水以保持培养基湿润,并加入少量干酵母作为跳虫食物。实验中选用的跳虫需经过同龄化培养,同龄化方法如下:挑选50~60只活跃成虫至新培养基中,加入少量干酵母,待成虫产卵(约2 d)后,移去成虫,每天观察,当观察到有幼虫孵出后,将幼虫转移到新培养基中培养。跳虫培养到23 d大时即可用于实验。

主要试剂为PCP(纯度98%,ULTRA scientific, USA)和丙酮(色谱纯,Fisher Chemical, USA),石英砂(Sigma-Aldrich),高岭土(化学纯,沪试),泥炭(德国Klasmann泥炭土876型)等。

1.2 暴露方法

本实验中的暴露介质为人工土壤,配制方法为:将泥炭、高岭土和石英砂按照1:2:7的质量比混合均匀,用CaCO3调节pH至(6.0±0.5)。配制不同浓度的PCP的丙酮溶液,加入到人工土壤中,搅拌混合均匀,使各处理组中PCP浓度分别为0、30、60、120和240 mg·kg-1干土,每个处理组做3个重复。加入一定量蒸馏水调节土壤含水量至土壤最大持水量的50%,分装至100 mL烧杯中(每个烧杯放入30 g湿土)。每个烧杯中加入30只23 d大的跳虫,用封口膜将烧杯封口,2 d后,用水浮法取出跳虫,放入离心管中,用液氮速冻后转入-80 ℃冰箱储存。

1.3 基因表达水平测定

跳虫RNA的提取利用微量样品总RNA提取试剂盒(天根),操作按试剂盒的说明书进行。利用琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测提取的RNA的完整性,利用Nanodrop测定RNA浓度,提取的RNA的OD260/OD280值在1.8~2.1范围内。利用FastQuant cDNA第一链合成试剂盒(天根)进行反转录,然后将各个cDNA样本稀释10倍备用。定量PCR反应在iCycle IQ2(Bio-rad, USA)仪器上进行,使用SuperRealPreMix Plus试剂盒(天根)。反应体系为20 μL,包括:10 μL的2×SuperReal PreMix Plus,2 μL的cDNA模板,6.8 μL的ddH2O,正向引物和反向引物各0.6 μL。反应条件为:95 ℃预变性15 min;95 ℃变性10 s,60 ℃退火20 s,72 ℃延伸30 s并采集荧光信号,40个循环;并设置溶解曲线以检测扩增产物的特异性。基因表达水平采用2-ΔΔCT法计算[24]。

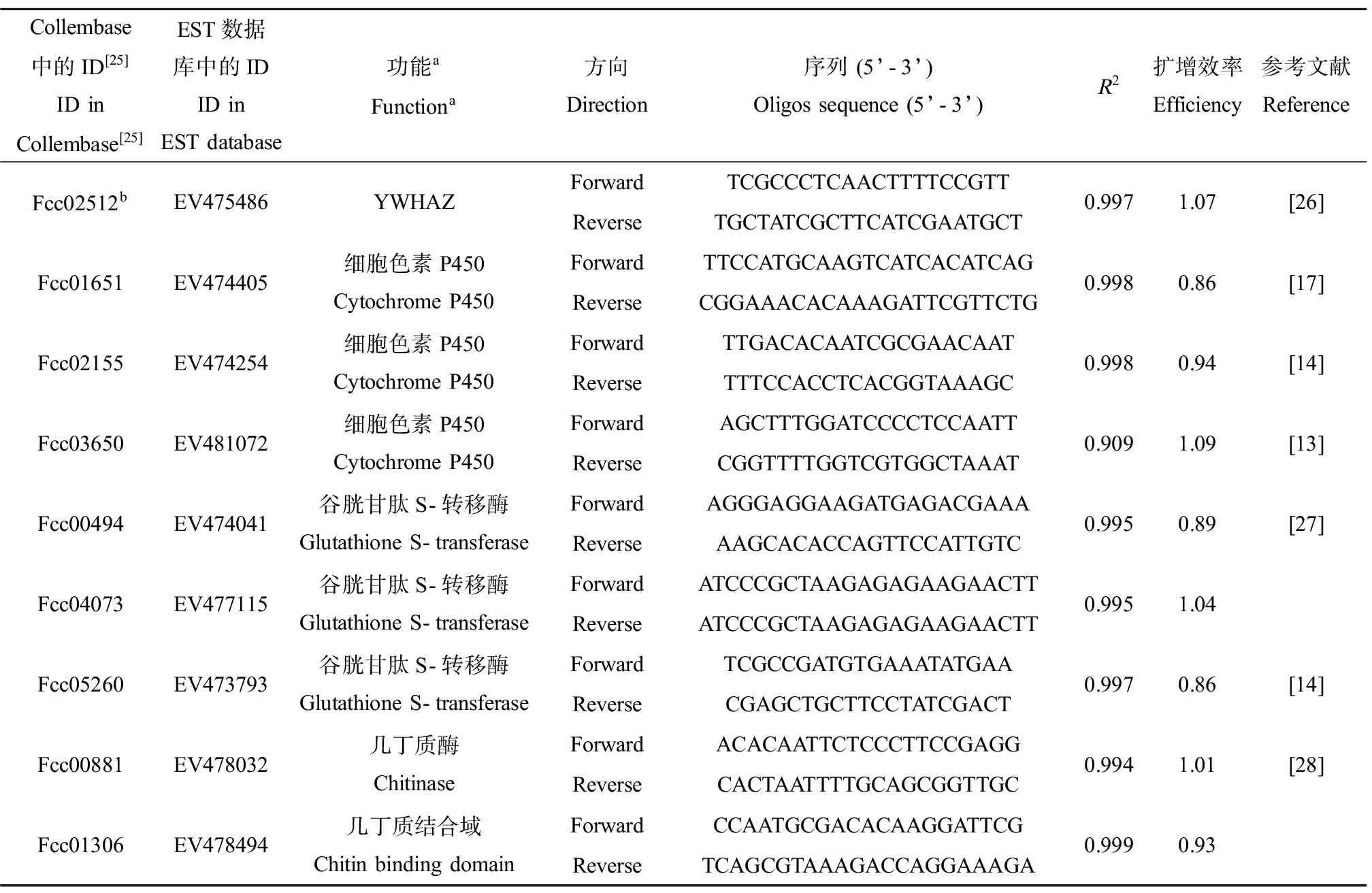

待测的基因及其引物如表1所示。部分基因的引物序列来自于已发表文献。对于基因Fcc04073和Fcc01306,根据其EST序列,利用Beacon Designer 8设计引物。对新设计的引物进行PCR反应,使用2×Taq PCR MasterMix(天根),反应体系为50 μL,包括:25 μL的2×Taq PCR MasterMix,5 μL的cDNA模板,16 μL的ddH2O,正向引物和反向引物各2 μL。反应条件为:94 ℃预变性3 min;94 ℃变性30 s,60 ℃退火30 s,72 ℃延伸30 s,30个循环;72 ℃延伸10 min。PCR产物经切胶纯化后,进行TA克隆,再进行测序,测序结果与目的基因片段比对后确认为需要的目的基因。各对引物qPCR扩增效率利用标准曲线法测定,从各个cDNA样本中取出一部分混合作为模板,进行5倍梯度稀释,共5个梯度。

1.4 数据处理

在数据满足(或经数据转换后满足)正态性(Shapiro-Wilk检验)和方差齐性(Levene检验)的前提下,进行单因素方差分析(One-Way ANOVA),利用Dunnett's t 检验进行多重比较,P<0.05表示差异显著。若数据不满足正态性和方差齐性,则利用Kruskal-Wallis单因素方差分析。数据分析和绘图利用SPSS 20.0和Origin 8.5完成。

2 结果(Results)

表1 qPCR中各个基因的引物Table 1 Primers used in the qPCR analysis

注:a根据Blastx和interPro注释结果,获得基因功能;bFcc02512(YWHAZ)被用作内参基因。

Note:aFunction is derived from the annotation results of Blastx and interPro;bFcc02512(YWHAZ) is used as reference gene.

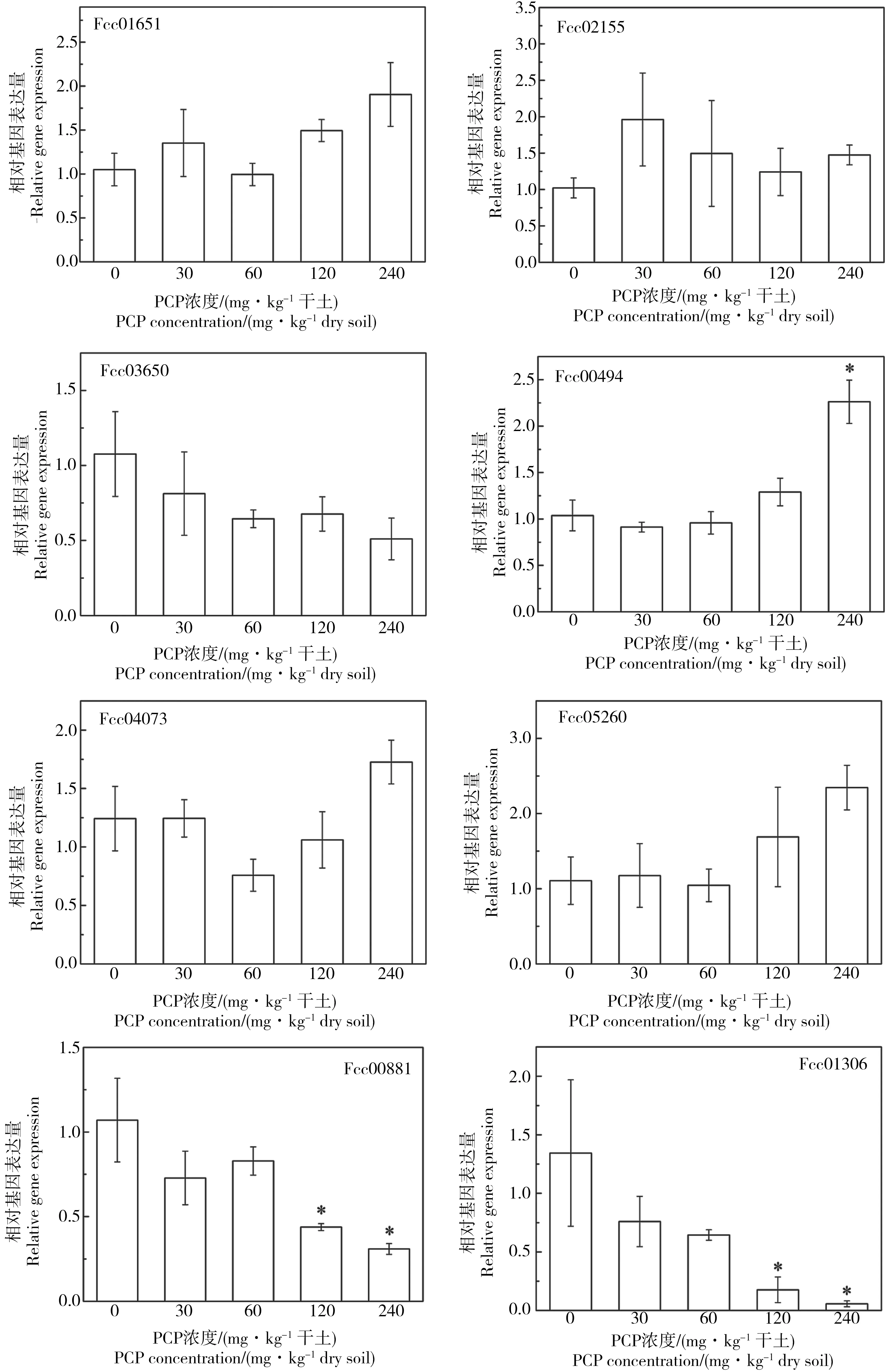

图1 PCP暴露对跳虫基因表达的影响(“*”)指该处理组与对照组相比差异显著,P<0.05)Fig. 1 Effects of PCP on gene expression of F. candida (“*”) denotes significant difference between treated and control groups, P<0.05)

PCP对跳虫的CYP450、GST基因和蜕皮相关基因的表达水平的影响如图1所示。CYP450基因Fcc01651、Fcc02155和Fcc03650的表达水平和PCP暴露浓度之间的效应-剂量关系不显著(P>0.05)。随着PCP浓度的增加,Fcc01651的表达水平先上下波动,后有逐渐增加的趋势;Fcc02155的表达水平先增加,后上下波动;Fcc03650的表达水平整体上呈现逐渐降低的趋势;但这些变化都不显著(P>0.05)。

跳虫GST基因Fcc04073和Fcc05260的表达水平与PCP暴露浓度之间的效应-剂量关系不显著(P>0.05)。在PCP浓度较高时,Fcc04073(120 mg·kg-1)和Fcc05260(120 mg·kg-1和240 mg·kg-1)的表达水平高于对照组,但并不显著(P>0.05)。在PCP浓度为30、60和120 mg·kg-1时,Fcc00494的表达水平与对照组相近;在PCP浓度为240 mg·kg-1时,GST基因Fcc00494的表达受到显著诱导(P<0.05),为对照组的2.18倍。

在PCP浓度为30 mg·kg-1和60 mg·kg-1时,几丁质酶基因Fcc00881的表达水平略有降低;在PCP浓度为120 mg·kg-1和240 mg·kg-1时,Fcc00881的表达受到显著抑制,分别为对照组的40.95%和28.89%(P<0.05)。随着PCP浓度的增加,几丁质结合蛋白基因Fcc01306的表达水平逐渐下降;在PCP浓度为120 mg·kg-1和240 mg·kg-1时,Fcc01306的表达受到显著抑制,分别为对照组的13.11%和4.20%(P<0.05)。

3 讨论(Discussion)

CYP450是一相代谢酶,它是一类含血红素的依赖NADPH的单加氧酶,催化许多物质的氧化代谢[29]。菲暴露2 d和7 d均发现能显著诱导跳虫CYP450基因的表达[13-14]。在本实验条件下,跳虫CYP450基因Fcc01651、Fcc02155和Fcc03650并未受到PCP的显著影响。基因表达会受暴露时间等的影响,本实验的暴露时间为2 d,这些CYP450基因的表达未发生显著变化,可能因为暴露时间较短。

GST是二相代谢酶,它广泛存在于各种好氧生物体内,在抗氧化、外源物质的代谢和解毒方面起着重要的作用[30]。GST可以通过促进还原脱氯化氢作用或与还原性谷胱甘肽的结合反应,将疏水性的有毒物质转化为具有亲水性的物质,从而更易于排出体外;此外,在有毒物质的代谢过程中可能产生氧自由基,GST在氧自由基的去除过程中起重要作用[31]。有研究报道,Cd[32]、吡虫啉[12]和菲[13-14]等显著诱导了跳虫GST基因的表达。PCP能对背角无齿蚌(Anodontawoodiana)产生氧化胁迫,诱导GST基因的表达[33-34]。本研究结果表明,PCP显著诱导了跳虫GST基因Fcc00494的表达,可能是因为GST参与了PCP的代谢,或者PCP引发了氧自由基的产生,GST参与了氧自由基的去除。跳虫GST基因Fcc04073和Fcc05260有被PCP诱导表达的趋势,但并不显著(P>0.05),PCP对不同跳虫GST基因(Fcc00494、Fcc04073和Fcc05260)作用不同,这可能是因为不同GST之间存在着差异,具有不同的特异性和亲和性[30-31]。Nota等[13]利用基因芯片研究菲暴露下跳虫基因表达谱的变化,实验结果显示,在暴露于浓度为24.95 mg·kg-1(干土)的菲时,跳虫GST基因Fcc00494、Fcc04073和Fcc05260都显著上调,但上调的程度不同。

蜕皮是跳虫重要的生命过程,影响着跳虫的生长和繁殖。跳虫在其一生中持续蜕皮,每次蜕皮会更新其表皮和中肠上皮,围食膜是中肠上皮的一部分[35-38]。跳虫表皮和围食膜的主要成分是几丁质和蛋白质[35-37, 39]。几丁质酶在蜕皮过程中起着降解几丁质的作用[40]。有研究报道,在干旱胁迫下,跳虫停止蜕皮,几丁质酶基因Fcc00881的表达显著下调,在补水后,跳虫恢复蜕皮,几丁质酶基因Fcc00881的表达显著上调[28]。几丁质结合域是一些围食膜蛋白质和几丁质酶的组成部分[41-44]。本研究结果表明,PCP显著抑制了跳虫几丁质酶基因Fcc00881和几丁质结合域基因Fcc01306的表达,说明PCP可能抑制了跳虫的蜕皮。已有报道表明PCP对水生节肢动物大型溞(Daphniamagna)的蜕皮有抑制作用[7],且雌二醇、乙烯雌酚和4-壬基酚等内分泌干扰物也会抑制大型溞的蜕皮[45]。蜕皮又主要是由蜕皮激素调控的,PCP对蜕皮的抑制可能是通过干扰蜕皮激素进行调控。有研究表明,PCP 能诱导摇蚊(Chironomusriparius)蜕皮激素受体基因和蜕皮激素应答基因E74的表达[46]。

近期,跳虫的基因组信息进一步完善,从中找到与蜕皮激素紧密相关的基因(如蜕皮激素受体基因),研究PCP暴露下这些基因的表达变化,将能进一步阐明PCP对跳虫内分泌系统的影响。生物体内含有多种CYP450和GST,找到跳虫其他的CYP450和GST基因开展相关研究,将能进一步了解PCP对跳虫代谢转化酶的影响。此外,基因表达会随着时间的变化而变化,而且不同基因的响应速度不同,本实验的暴露时间为2 d,测定不同时间暴露下的基因表达,将能进一步了解PCP对跳虫基因表达的影响。自然土壤和人工土壤的性质存在着差异,而土壤性质能影响污染物的毒性,本实验使用的土壤是人工土壤,应进一步对具有代表性的自然土壤开展相关研究。

[1] Zheng W, Yu H, Wang X, et al. Systematic review of pentachlorophenol occurrence in the environment and in humans in China: Not a negligible health risk due to the re-emergence of schistosomiasis [J]. Environment International, 2012, 42: 105-116

[2] Campbell L M, Muir D C G, Whittle D M, et al. Hydroxylated PCBs and other chlorinated phenolic compounds in lake trout (Salvelinusnamaycush) blood plasma from the great lakes region [J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2003, 37(9): 1720-1725

[3] Ge J, Pan J, Fei Z, et al. Concentrations of pentachlorophenol (PCP) in fish and shrimp in Jiangsu Province, China [J]. Chemosphere, 2007, 69(1): 164-169

[4] Zheng M H, Zhang B, Bao Z C, et al. Analysis of pentachlorophenol from water, sediments, and fish bile of Dongting Lake in China [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2000, 64(1): 16-19

[5] U S Environmental Protection Agency. Toxicological review of pentachlorophenol [R]. Washington, DC: US EPA, 2010

[6] Orton F, Lutz I, Kloas W, et al. Endocrine disrupting effects of herbicides and pentachlorophenol:Invitroandinvivoevidence [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009, 43(6): 2144-2150

[7] Chen Y, Huang J, Xing L, et al. Effects of multigenerational exposures ofD.magnato environmentally relevant concentrations of pentachlorophenol [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2014, 21(1): 234-243

[8] Xu T, Zhao J, Hu P, et al. Pentachlorophenol exposure causes Warburg-like effects in zebrafish embryos at gastrulation stage [J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2014, 277(2): 183-191

[9] Fountain M T, Hopkin S P.Folsomiacandida(Collembola): A "standard" soil arthropod [J]. Annual Review of Entomology, 2005, 50: 201-222

[10] Campiche S, L'Ambert G, Tarradellas J, et al. Multigeneration effects of insect growth regulators on the springtailFolsomiacandida[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2007, 67(2): 180-189

[11] Crouau Y, Chenon P, Gisclard C. The use ofFolsomiacandida(Collembola, Isotomidae) for the bioassay of xenobiotic substances and soil pollutants [J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 1999, 12(2): 103-111

[12] Sillapawattana P, Schäffer A. Effects of imidacloprid on detoxifying enzyme glutathione S-transferase onFolsomiacandida(Collembola) [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23: 11111-11119

[13] Nota B, Bosse M, Ylstra B, et al. Transcriptomics reveals extensive inducible biotransformation in the soil-dwelling invertebrateFolsomiacandidaexposed to phenanthrene [J]. BMC Genomics, 2009, 10: 236

[14] Holmstrup M, Slotsbo S, Schmidt S N, et al. Physiological and molecular responses of springtails exposed to phenanthrene and drought [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2014, 184: 370-376

[15] Maria V L, Ribeiro M J, Amorim M J. Oxidative stress biomarkers and metallothionein inFolsomiacandida—Responses to Cu and Cd [J]. Environmental Research, 2014, 133: 164-169

[16] de Boer M E, Ellers J, van Gestel C A, et al. Transcriptional responses indicate attenuated oxidative stress in the springtailFolsomiacandidaexposed to mixtures of cadmium and phenanthrene [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2013, 22(4):619-631

[17] Janssens T K, Giesen D, Marien J, et al. Narcotic mechanisms of acute toxicity of chlorinated anilines inFolsomiacandida(Collembola) revealed by gene expression analysis [J]. Environment International, 2011, 37(5): 929-939

[18] Mehmood Z, Williamson M P, Kelly D E, et al. Metabolism of organochlorine pesticides: The role of human cytochrome P450 3A4 [J]. Chemosphere, 1996, 33(4): 759-769

[19] Wang Y J, Ho Y S, Chu S W, et al. Induction of glutathione depletion, p53 protein accumulation and cellular transformation by tetrachlorohydroquinone, a toxic metabolite of pentachlorophenol [J]. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 1997, 105(1): 1-16

[20] Huang Y, Xun R, Chen G, et al. Maintenance role of a glutathionyl-hydroquinone lyase (PcpF) in pentachlorophenol degradation bySphingobiumchlorophenolicumATCC 39723 [J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2008, 190(23):7595-7600

[21] Yu L, Zhao G, Feng M, et al. Chronic exposure to pentachlorophenol alters thyroid hormones and thyroid hormone pathway mRNAs in zebrafish [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2014, 33(1): 170-176

[22] Guo Y, Zhou B. Thyroid endocrine system disruption by pentachlorophenol: Aninvitroandinvivoassay [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2013, 142-143: 138-145

[23] Marshall V G, Kevan D K M. Preliminary observations on the biology ofFolsomiacandidaWillem, 1902 (Collembola: Isotomidae) [J]. The Canadian Entomologist, 1962, 94(6): 575-586

[24] Livak K J, Schmittgen T D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT Method [J]. Methods, 2001, 25(4): 402-408

[25] Timmermans M J, de Boer M E, Nota B, et al. Collembase: A repository for springtail genomics and soil quality assessment [J]. BMC Genomics, 2007, 8(1): 341

[26] de Boer M E, de Boer T E, Marien J, et al. Reference genes for qRT-PCR tested under various stress conditions inFolsomiacandidaandOrchesellacincta(Insecta, Collembola) [J]. BMC Molecular Biology, 2009, 10: 54

[27] Qiao M, Wang G P, Zhang C, et al. Transcriptional profiling of the soil invertebrateFolsomiacandidain pentachlorophenol-contaminated soil [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2015, 34(6): 1362-1368

[28] Waagner D, Bayley M, Marien J, et al. Ecological and molecular consequences of prolonged drought and subsequent rehydration inFolsomiacandida(Collembola) [J]. Journal of Insect Physiology, 2012, 58(1): 130-137

[29] Menzel R, Bogaert T, Achazi R. A systematic gene expression screen ofCaenorhabditiseleganscytochrome p450 genes reveals CYP35 as strongly xenobiotic inducible [J]. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2001, 395(2): 158-168

[30] Sherratt P J, Hayes J D. Glutathione S-transferases [M]//Loannides C. Enzyme Systems that Metabolise Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. Wiley, 2002: 319-352

[31] Enayati A A, Ranson H, Hemingway J. Insect glutathione transferases and insecticide resistance [J]. Insect Molecular Biology, 2005, 14(1): 3-8

[32] Nakamori T, Fujimori A, Kinoshita K, et al. mRNA expression of a cadmium-responsive gene is a sensitive biomarker of cadmium exposure in the soil collembolanFolsomiacandida[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2010, 158(5): 1689-1695

[33] Liu Q, Shang X, Ma Y, et al. Isolation and characterization of two glutathione S-transferases from freshwater bivalveAnodontawoodiana: Chronic effects of pentachlorophenol on gene expression profiles [J]. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 2017, 64: 339-351

[34] Xia X, Hua C, Xue S, et al. Response of selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase in the freshwater bivalveAnodontawoodianaexposed to 2,4-dichlorophenol, 2,4,6-trichlorophenol and pentachlorophenol [J]. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 2016, 55: 499-509

[35] Tebbe C C, Czarnetzki A B, Thimm T. Collembola as a Habitat for Microorganisms [M]// König H, Varma A. Intestinal Microorganisms of Termites and Other Invertebrates. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2006: 133-153

[36] Timmermans M J, Roelofs D, Nota B, et al. Sugar sweet springtails: On the transcriptional response ofFolsomiacandida(Collembola) to desiccation stress [J]. Insect Molecular Biology, 2009, 18(6): 737-746

[37] Thimm T, Hoffmann A, Borkott H, et al. The gut of the soil microarthropodFolsomiacandida(Collembola) is a frequently changeable but selective habitat and a vector for microorganisms [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1998, 64(7): 2660-2669

[38] Humbert W. The midgut ofTomocerusminorLubbock (Insecta, Collembola): Ultrastructure, cytochemistry, ageing and renewal during a moulting cycle [J]. Cell and Tissue Research, 1979, 196(1): 39-57

[39] Frederik Nijhout H. Arthropod Developmental Endocrinology [M]//Minelli A, Boxshall G, Fusco G. Arthropod Biology and Evolution: Molecules, Development, Morphology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013:123-148

[40] Merzendorfer H. Chitin metabolism in insects: Structure, function and regulation of chitin synthases and chitinases [J]. Journal of Experimental Biology, 2003, 206(24): 4393-4412

[41] Suetake T. Chitin-binding proteins in invertebrates and plants comprise a common chitin-binding structural motif [J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2000, 275(24):17929-17932

[42] Shen Z, Jacobs-Lorena M. A type I peritrophic matrix protein from the malaria vectorAnophelesgambiaebinds to chitin. Cloning, expression, and characterization [J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1998, 273(28):17665-17670

[43] Casu R, Eisemann C, Pearson R, et al. Antibody-mediated inhibition of the growth of larvae from an insect causing cutaneous myiasis in a mammalian host [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1997, 94(17): 8939-8944

[44] Elvin C M, Vuocolo T, Pearson R D, et al. Characterization of a major peritrophic membrane protein, peritrophin-44, from the larvae ofLuciliacuprina[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1996, 271(15): 8925

[45] Brennan S J, Brougham C A, Roche J J, et al. Multi-generational effects of four selected environmental oestrogens onDaphniamagna[J]. Chemosphere, 2006, 64(1): 49-55

[46] Morales M, Martínez-Paz P, Martín R, et al. Transcriptional changes induced byinvivoexposure to pentachlorophenol (PCP) inChironomusriparius(Diptera) aquatic larvae [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2014, 157: 1-9