Placement instability among young people removed from their original family and the likely mental health implications

2017-11-29SimonRICESueCOTTONKristenMOELLERSAXONECathrineMIHALOPOULOSAnneMAGNUSCarolHARVEYCathyHUMPHREYSStephenHALPERINAngelaSCHEPPOKATPatrickMCGORRYHelenHERRMAN

Simon RICE, Sue COTTON, Kristen MOELLER-SAXONE, Cathrine MIHALOPOULOS,Anne MAGNUS, Carol HARVEY, Cathy HUMPHREYS, Stephen HALPERIN, Angela SCHEPPOKAT ,Patrick MCGORRY, Helen HERRMAN,*

•Original research article•

Placement instability among young people removed from their original family and the likely mental health implications

Simon RICE1,2,3, Sue COTTON1,2, Kristen MOELLER-SAXONE1,2, Cathrine MIHALOPOULOS4,Anne MAGNUS4, Carol HARVEY5,6, Cathy HUMPHREYS7, Stephen HALPERIN1,2,3, Angela SCHEPPOKAT1,2,Patrick MCGORRY1,2,3, Helen HERRMAN1,2,*

out-of-home care, residential care, foster care, adolescent mental health

1. Introduction

Young people in out-of-home care in Australia and other countries are vulnerable to poor health outcomes compared to their peers who grow up in biological families.[1,2]Their health and wellbeing problems can be complex and difficult to manage including developmental delay, substance misuse, sexual and mental health problems.[3,4]The numbers of young people entering out-of-home care are increasing,[5]and while many young people in out-of-home care settings demonstrate resilience across multiple domains of functioning[6]and may subsequently thrive, the majority appear to experience significant difficulties in the transition to adulthood.[7]An evidence-base is needed to promote effective intervention with these young people. Adolescence is an important stage when mental health needs can be high, yet little is known about the characteristics of young people aged 12-17 years in out-of-home care, nor the prevalence of factors that have an adverse effect on their mental health.

Young people are legally required to leave the state protection of out-of-home care at the age of 18 in Australia. They then encounter limited opportunities for work or further education[8]and are at significant risk of homelessness.[9]A longitudinal study of young people leaving care in Australia reported that nearly 50% had attempted suicide within four years.[10]One in three young women had become pregnant or given birth within 12 months of leaving care.[11]International research has found that up to 35% of young people in state care had become homeless within 12 months of leaving care.[12]

International research also showed the main predictors of poor mental health for young people in out-of-home care were placement instability,intellectual disability, and either older age at entry into care, or very early placement into residential care.[13,14]Little is known about potential gender differences in care type characteristics. The main protective factor is younger age at entry into home-based care (i.e., kinship or foster care).[15,16]According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), the number of children and young people in out-of-home care is growing by 5% per annum, and while the overall number of children and young people in residential care (i.e., outof-home care provided in a small residence with paid staff) is relatively low (7%), almost all (84.6%) within this residential care group are aged 10 or older.[17]Of great concern are the numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in out-of-home care, with a likelihood of being in care vastly exceeding that of non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.[17]

Young people in the out-of-home care sector who experience placement disruption and instability(i.e. multiple short-term placements, failed family reunification) are at significant risk of poorer health outcomes. Research suggests that placement instability in the out-of-home care sector is relatively common,[18,19]though a trend in Australian data suggests that kinship care is more stable than other forms of care.[20]Instability within out-of-home care environments has significant implications for the development of secure attachment,[16]although some forms of care (i.e., kinship care) appear to be more protective than others against the development of attachment problems.[20]When a young person experiences a number of sequential short-term out-ofhome care placements, there are likely to be difficulties in undertaking a proper assessment of her or his needs.[21,22]Australian data showed that young people settled in one placement for most (i.e. 75%) of their time in out-of-home care experienced a wide range of better outcomes (i.e., employment, stability of housing,education, substance use, mental health, criminal behaviour) than those with multiple placements.[11]

At present, little research exists on the background demographic and care type characteristics of young people in Australia’s out-of-home care sector. In particular, there is no reliable estimate of the number of young people identifying as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, nor of culturally and linguistically diverse young people. These groups are likely to have particular needs influenced by their backgrounds, experiences and cultures. Such data are urgently needed as a step towards improved interagency collaboration and intensified use and evaluation of new and proven effective interventions, and application of culturally appropriate supports for young people in care.[23]In this paper, we report data from a Census of young people aged 12-17 years living in out-of-home care within north-western and south-eastern Melbourne in 2014.The Census was designed to gather information on characteristics that may predispose young people in care to mental health difficulties and that may guide or be amenable to intervention. Specifically, we focus on demographic characteristics of these young people as well as differences in placement history and care type(home-based versus residential care).

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

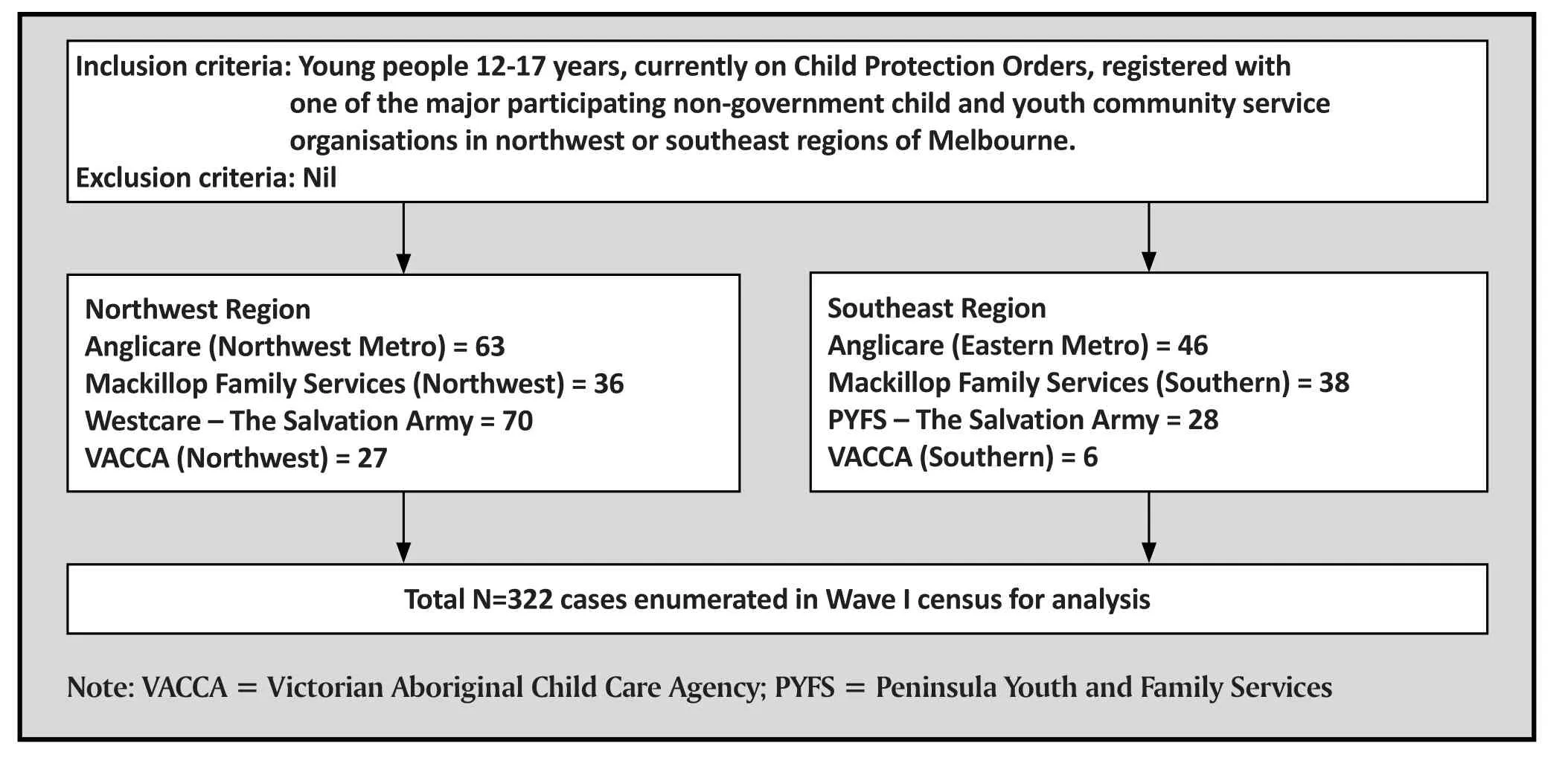

The Census involved collection of demographics,placement information, cultural and linguistic backgrounds, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders status, and registered disability status of youth on child protection orders. The Census was conducted between 18th August 2014 and 29th August 2014 across four non-government child and youth community service organisations (CSOs) in Melbourne. These organisations are broadly representative of the main providers of out-of-home care for children and young people in the Northwest and Southeast Region of Melbourne (see Figure 1).

Six care types were noted:(1) adolescent care program (volunteer foster carers providing supportive home environment and care to young people aged 12 -17 years); (2) foster care (care is provided in the private home of a substitute family receiving payment intended to cover the child’s living expenses); (3) therapeutic foster care (home-based treatments provided by foster carers who have received specialised training); (4)kinship care (caregiver is a family member or a person with a pre-existing relationship with the child);(5) lead tenant (volunteer carer who lives in a house with one or two young people who are learning independent living skills) and (6) residential care (out-of-home care provided in a residence where there are paid staff,including rostered staff within Victorian CSOs where there are typically no more than four young people in one house).

2.2 Materials

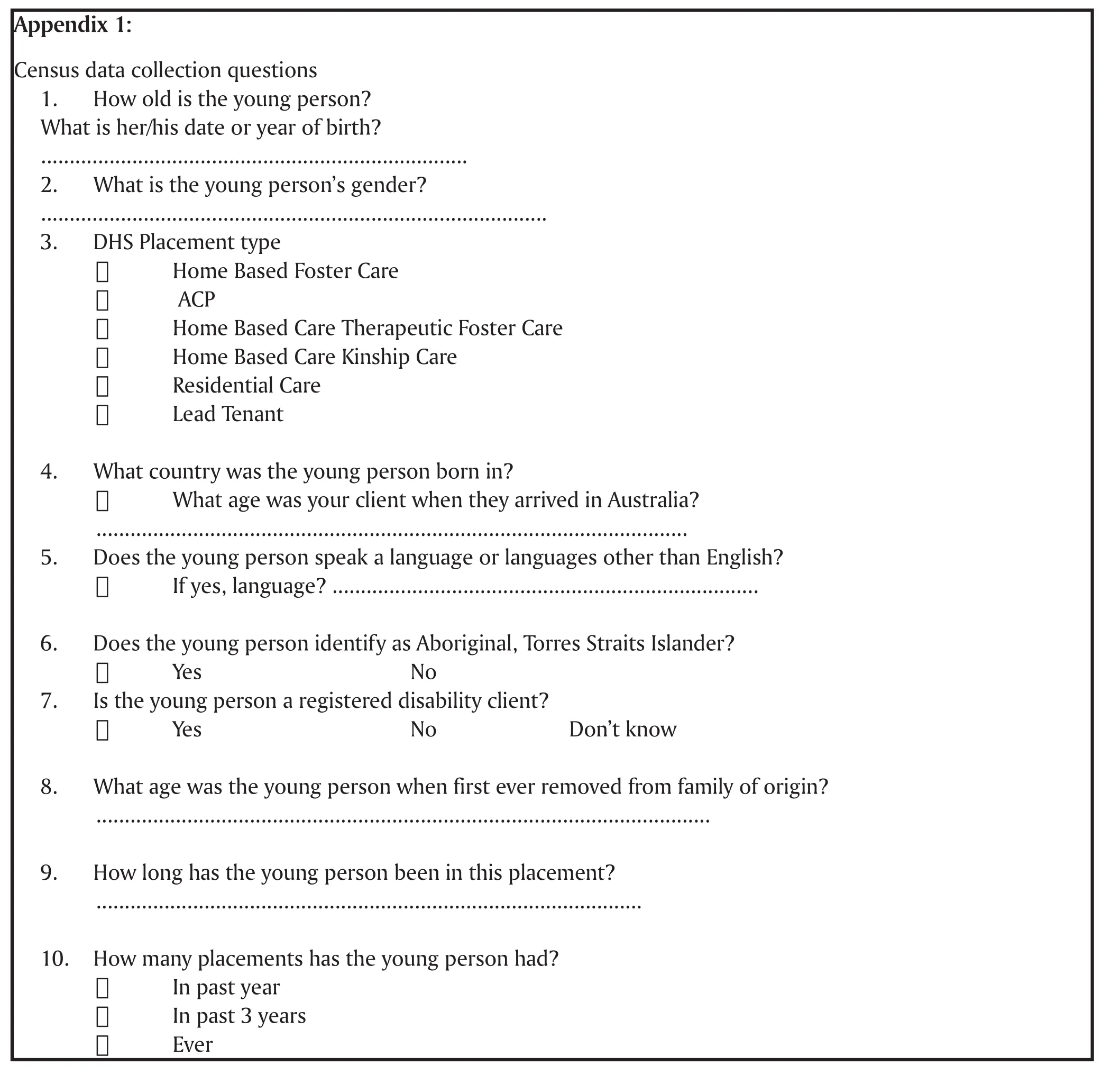

The Census data collection tool comprised 10 questions. These questions assessed age, gender,placement type, country of birth, languages other than English, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status,registered disability status, age of first removal from family of origin, and number of previous placements over the (a) past year, (b) past 3 years, and (c) lifetime(see Appendix 1).

2.3 Procedure

Approval was granted by The University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (1340674). The Victorian Department of Human Services Research Coordinating Committee and CSO research committees also provided approval. Research assistants attended each of the CSOs and worked directly with centre staff to identify and record details of participants for the Census.

2.4 Statistical Methods

All analyses were completed in SPSS 22.0. Summary statistics were calculated and Pearson correlation was used to examine the association of age of first removal from family of origin and placement duration.Group differences (i.e., gender, care type and cultural background) were evaluated using chi-square, t-test and factorial analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with age at census treated as a covariate. Bonferroni adjusted post-hoc analyses determined significant differences between groups. Comparisons were made between home-based care (aggregation of foster, therapeutic foster, adolescent care program, kinship, and lead tenant) and residential care types, regarding age,number of placements in past year (i.e., categorised as 1, 2, 3-4, 5-10), and lifetime placements (i.e.,categorised as 1, 2, 3-4, 5-10, 10+).

3. Results

3.1 Background characteristics

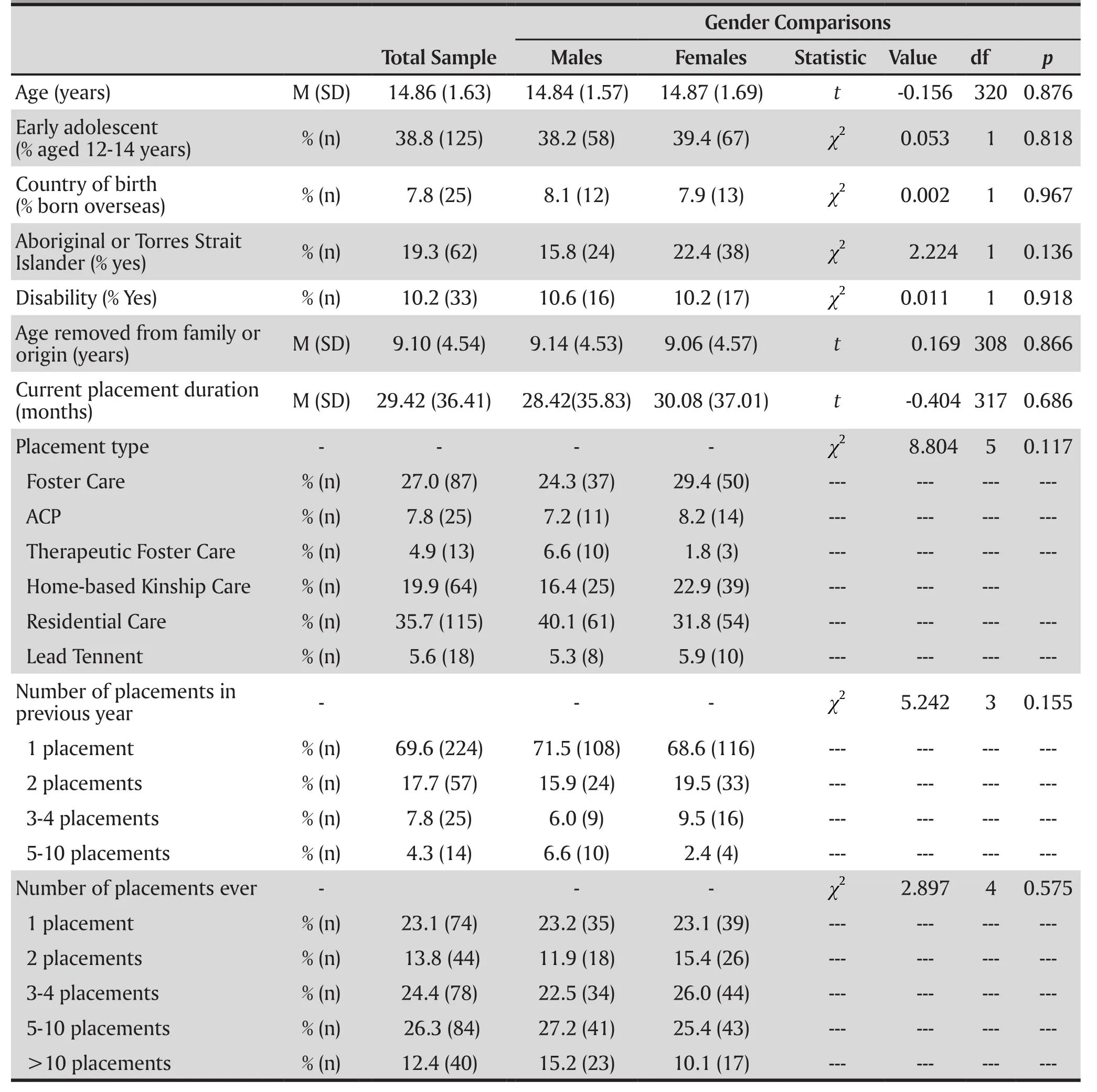

The Census of 322 young people was almost evenly split by gender, with 47.2% (n=152) males and 52.8% (n=170)females. The mean (SD) age of young people was 14.9(1.6) with those enumerated ranging from 12 to 17 years,median=15 (see Table 1). Overall 38.8% (n=125) of the cohort were aged between 12-14 years of age.

Figure 1. Flowchart of study

The minority had registered disability status (10.4%,n=33), or were born overseas (8.0%, n=25). For those born overseas, region of birth included Africa (i.e.,Congo, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone n=14), Asia (i.e., Burma,Japan, Vietnam; n=3), Middle East (i.e., Iraq, Syria;n=2) and New Zealand / Canada (n=6). The mean age of arrival in Australia was 8.2 (4.1) years (n=17, min=3,max=16). Relatively few young people spoke an additional language (10.5%, n=34). The most frequent other languages were Arabic (n=7) and Vietnamese(n=5), and sign language (i.e., AUSLAN, n=5). A total of 19.3% (n=62) of the young people in the Census identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders.Relative to the general population, young people from Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander backgrounds were overrepresented (3% of the total Australian population is identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background24). There were no significant gender differences in the Census across any of the background demographic variables (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics & Care Characteristics

3.2 Care characteristics

Of the single groupings, residential care was the most common care type (35.7%, n=115), followed by homebased foster care (27.0%, n=87), and home-based kinship care (19.9%, n=64) (see Table 1). Age of first removal from original family ranged from 0–17 years,with a mean (SD) of 9.10 (4.54) years. Half the sample were first removed from their families earlier than 10 years of age (0-5 years, 20.4%, n=59; 6-10 years, 30.4%,n=88), with the remaining 11-15 years (45%, n=130)and 16-17 years (3.7%, n=12). There was no gender difference for age of first removal. Children from an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background were significantly younger at age of first removal with a mean (SD) of 7.02 (4.6) years than non-Indigenous children with a mean (SD) of 9.58 (4.4), t(308)=3.96,p<0.001. Those in residential care settings were marginally older at 15.15 (1.41) years than that in home-based care at 14.71 (1.72) years, t(320)=-2.253,p<0.018. Given this, age was treated as a covariate in relevant between-group analyses below.

3.3 Number of placements

In the previous year, 69.6% (n=224) of children had only one previous placement, 17.7% (n=57) had two placements, 7.8% (n=25) had 3-4 placements, and 4.3%(n=14) had 5-10 placements. Over their lifetime, 23.1%(n=74) of children had only one previous placement,13.8% (n=44) had two placements, 24.4% (n=78) had 3-4 placements, 26.3% (n=84) had 5-10 placements,and 12.4% (n=40) had more than 10 placements.Accordingly, 63.1% of the sample were considered to have experienced placement instability (i.e., ≥3 lifetime placements before age 18). There were no significant associations between gender or Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background for placement instability,either previous year, or lifetime (all p>0.05).

3.4 Duration of current placement

Duration at current placement ranged from 0 to 180 months with a mean(SD) 29.42 (36.41). Earlier age of removal was associated with longer time (months) spent at current placement (r= -0.48, p<0.001). The effects of gender and placement type on length at current placement were evaluated by factorial ANCOVA. There was a significant effect of placement type on the mean duration of the current placement F(5,305)=12.595,p<0.001, η2=0.171, though neither the gender main effect, the gender × placement type interaction, or covariate (age) were significant. Bonferonni adjusted post hoc tests indicated a pattern of significantly shorter duration of current placement for those in residential or lead tenant care relative to foster care or kinship care (see Table 3 for post hoc tests and means).

3.5 Number of lifetime placements

Number of lifetime placements ranged from 1 to 22 with a mean (SD) of 4.74 (4.19). When examined categorically, there was a significant association between placement instability and care type (χ2[18,N=320]=63.018, p<0.001). Table 2 shows that relativeto other care types, kindship care was associated with greater placement stability (i.e., either 1 or 2 lifetime placements). Factorial ANCOVA indicated a significant effect of placement type on the total number of lifetime placements F(5,307)=8.247,p<0.001, η2=0.118, though neither the main effect for gender, the gender × placement type interaction, or the covariate (age) were significant.Post hoc tests indicated several significant group differences, with young people in residential care experiencing significantly more lifetime placements at 6.29 (4.92) compared to those in foster care 4.35 (4.05),Bonferonni adjusted p=0.010 (M=4.35, SD=4.05,p=0.010) and (kinship care mean [SD] 2.48 [1.93],Bonferonni adjusted p<0.001), while those in kinship care experienced fewer placements than those in lead tenant placements (mean [SD] 5.72 [3.74], Bonferonni adjusted p=0.036). Hence, young people in kinship care were more likely than other care types to have a single placement, and experienced significantly fewer lifetime placements than young people in residential care or lead tenant care.

Table 2. Previous lifetime placements by current placement type

Table 3. Duration (months) of Current Placement by Placement Type and Gender

3.6 Home-based and residential care comparisons

Analyses were undertaken comparing those young people currently in home-based care types (aggregation of foster, therapeutic foster, adolescent care program,kinship, and lead tenant) with those currently in residential care by gender. Factorial ANCOVA indicated that youth in residential care had almost double the number of previous lifetime placements than youth in home-based care, respective means 6.29 (4.92) and 3.88 (3.41), F(1,315)=26.082, p<0.001, η2=0.076. A significant difference was also observed for number of placements in the previous year where those in residential care 1.83 (1.57) had on average more lifetime placements than those in home-based care 1.34(1.42), F(1,317)=8.458, p=0.004, η2=0.026. There was no significant gender difference, gender × care type interaction, or covariate (age) in these analyses.Nonetheless, youth in home-based care were almost two years younger at age of first removal 8.50 (4.59),compared to those in residential care 10.20 (4.27) ,t(308)=-3.18, p=0.002. Hence, residential care was associated with greater placement instability, and older age of first removal from family of origin.

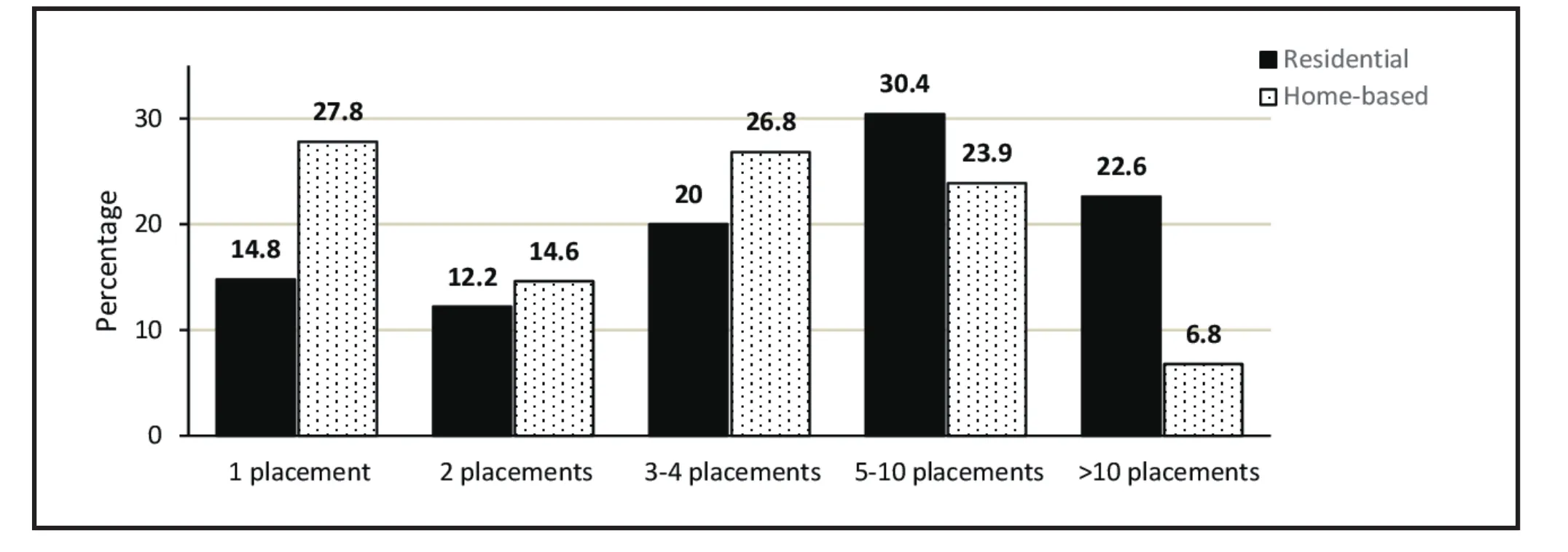

Chi-square analyses were conducted to assess for care type (home-based / residential) difference in number of previous year, and lifetime placements. The effect on number of placements in previous year was not significant, but the lifetime (categorical) placements by care type was significant, χ2(18, N=320)=41.93,p<0.001. Youth in residential care settings were more than three times as likely to have experienced >10 placements than were those in home-based care. Relative to care type, for those in residential care 73% (n=84)had experienced ≥3 placements, while for those in home-based care, 57.5% (n=118) had experienced ≥3 placements (see Figure 2). Youth from an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background were more frequently placed in home-based care settings (79.0%, n=40) than residential care (21.0%, n=13), χ2(1, N=322)=7.27,p=0.007.

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

This research presented the first systematic census of characteristics of young Australians (12-17 years) in the out-of-home care sector. It includes young people linked with the major community service organisations(CSOs) engaged in this work in two of the four regions of metropolitan Melbourne. Only by doing such descriptive studies are background population status and trends identified. The young people were, on average, removed from their family of origin by the State in mid-childhood. The census reveals that three out of four of these young people have a lifetime historyof more than one placement in home-based or residential care programs, with more than a third having experienced five or more lifetime (to date) placements. Based on the definition established by Webster and colleagues[18](i.e.,≥3 lifetime placements), almost two thirds (63.1%) of those enumerated experienced placement instability. The census also included a comparatively large proportion of young people who were from an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island background. In addition, close to 10% of those enumerated were born overseas, suggesting there may be specific cultural needs for this population. When taken together, and from the perspective that secure or reparative attachments are known to be associated with positive mental health and functioning,[16,20]the present figures warrant further examination, exploration of contributing factors and concern.

Figure 2. Number of lifetime placements by home-based/residential care type

4.2 Limitations

The reported rate of the young people enumerated in the census with a registered disability (10%) was lower than our expectations, and our CSO partners since previously published reports have identified between 22% and 42% young people living in out-of-home care have a registered disability.[28]This discrepancy could possibly reflect a lack of access to relevant CSO assessment and diagnosis records, although we could detect no indication of this. A further limitation is that our Census enumerated only those young people in the outof-home care sector who are registered with CSOs. Given that a growing proportion of young people are placed directly in kinship care by the state child protection services without invoking the case management services of CSOs (as state child protection protocols change), this data is necessarily incomplete. Further, as census data was collated at CSO sites in a de-identified manner, it is not possible to link this to individual health or mental health outcomes in further studies.

A second census of the same CSOs will be conducted in 2016 and any change in the rates examined here will be reported, providing valuable trend data over a three year period. A number of current initiatives are designed to respond to emotional difficulties and disturbed behaviour among young people in home-based and residential out-of-home care(e.g., therapeutic foster care, Roadmap for Reform[29]). In particular, The Ripple Project[30]is evaluating a universal mental health promotion intervention that provides capacity development and support to community case managers and carers. It is hoped that such companion work will strengthen the therapeutic capacities of outof-home carers of young people and have an impact on rates of placement stability. Greater placement stability is likely to be an important mediating variable between improved health and function of carers and that of the young people in out-of-home care.

4.3 Implications

To our knowledge, these data are unique. While previous work has examined placement instability for those removed in early childhood (i.e., between 0 and 6 years[18]), we are aware of only one other Australian study to have reported placement history (i.e.,instability) of young people in the out-of-home care sector across the 12-17 age range.[25]Our study includes a high proportion of young people living in residential care (35.7% of the sample), compared with 5% when all age groups and all care classifications (including those young people who are sent directly to kinship care without CSO case management) are considered.[17]The Pathways of Care longitudinal study of children in out-of-home care in Australia included children and young people in all care classifications. It showed that 42% remained in their current placement for 18 months or more: compared with the current study, a longer period than that observed for young people in residential care, but substantially shorter than that for home-based care.[25]Of note, in the current study,young people in kinship care were more likely than other care types to experience stable placements(i.e., <3 lifetime placements), and reported overall significantly fewer lifetime placements than those in residential or lead tenant care. Comparable work from the US has examined differential patterns of placement instability, reporting a sizeable minority (19.8%) as having an unstable pattern characterised by multiple brief placements (less than 9 months), associated with significantly higher internalising and externalising behaviour problems.[19]

Given the paucity of existing data regarding placement instability, significant informational needs exist (for, carers, policy makers, protective services and researchers) concerning young people living within the out-of-home care sector throughout Australia.[23]The lack of routinely collected and publicly available information about the number, characteristics and circumstances of young people living in out-of-home care in Melbourne is a situation similar in other Australian states and in other countries.[13]

Existing literature[11,21]indicated that placement stability was one of the essential ingredients required for young people in care to overcome their difficulties.Hence, stable care conditions have a greater chance of ameliorating the difficulties often associated with interpersonal trauma and helping the youth in these circumstances to gain an education, employment and a life as a citizen with good mental health. The present study indicates for the first time the degree of current and lifetime instability by care type in this population.The current configuration of the out-of-home care system appears to offer stable care to a minority of its residential youth, 50% of its home based youth, and the associations of placement stability/instability with mental health outcomes need further study.

Home-based foster or kinship care is designed as a humane replacement for the large institutions and orphanages of bygone days in our community.Orphanages and institutions create conditions recognised as deleterious for mental health and future function as adults.[26]These include strict routines,lack of personal relationships and isolation from wider society. Many countries promote foster-care programs and their equivalents as a better care solution.However, these programs can be just as harmful as institutionalization to a child’s future mental health and function if the care is unstable.[27]Further, in many cases carers have little access to support for themselves and their role as de facto parents in demanding circumstances.

5. Conclusions

Significant lifetime placement instability has been identified in the population of young people living in out-of-home care in Melbourne. Since instability is a risk factor for mental health problems and consequent life-time opportunities regarding employment,education and criminality, further examination of the causal pathways and implementation research are needed so that the risks can be redressed with effective interventions where possible.

Funding

The Ripple Study is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Targeted Call for Research 1046692. Prof. Sue Cotton is supported by NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1061998).Prof. Helen Herrman is supported by an NHMRC Fellowship. Prof. Cathrine Mihalopoulos is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (APP1035887). Dr Simon Rice is supported by an Early Career Fellowship from the Society of Mental Health Research.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Approval was granted by The University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (1340674). The Victorian Department of Human Services Research Coordinating Committee, Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (2014-046) and CSO research committees also provided approval.

Authors’ contribution

The study was originally conceived by HH, SC, CM, AM,CH, SH and PM. Management of data collection, data cleaning and project oversight undertaken by KMS and AS. The data analysis plan was developed by HH, KMS,SC and SR. Data analysis and reporting was undertaken by SC and SR. All authors collaborated significantly to manuscript development and editing. All authors approved the final submitted version.

1. Nathanson D, Tzioumi D. Health needs of Australian children living in out-of-home care. J Paediatr Child Health.2007;43(10): 695-699. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01193.x

2. Vinnerljung B, Sallnäs M. Into adulthood: A follow- up study of 718 young people who were placed in out- o fhome care during their teens. Child & Family Social Work.2008;13(2): 144-155. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2007.00527.x

3. Sawyer MG, Carbone JA, Searle AK, Robinson P. The mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in homebased foster care. Med J Aust. 2007;186(4): 181

4. Webster SM, Temple-Smith M. Children and young people in out-of-home care: are GPs ready and willing to provide comprehensive health assessments for this vulnerable group? Aust J Prim Health. 2010;16(4): 296-303. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/PY10019

5. Zwi KJ, Henry RL. 13. Children in Australian society. Med J Aust. 2005;183(3): 154

6. Daining C. Resilience of youth in transition from outof-home care to adulthood. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2007;29(9): 1158-1178. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.04.006

7. Mendes P. Graduating from the child welfare system a case study of the leaving care debate in Victoria, Australia.J Soc Work. 2005;5(2): 155-171. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468017305054970

8. Mendes P, Moslehuddin B. From dependence to interdependence: Towards better outcomes for young people leaving state care. Child Abuse Rev. 2006;15(2): 110-126. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/car.932

9. Cummins P, Scott D, Scales B. Report of the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry. Melbourne: Department of Premier and Cabinet; 2012

10. Cashmore J P M. Longitudinal Study of Wards Leaving Care.Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre; 2007

11. Cashmore J, Paxman M. Predicting after‐care outcomes:the importance of ‘felt’ security. Child & Family Social Work 2006;11(3): 232-241. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00430.x

12. Barton S, Gonzalez R, Tomlinson P. Therapeutic Residential Care for Children and Young People. London: Jessica Kingsley;2012

13. Stein M, Dumaret AC. The mental health of young people aging out of care and entering adulthood: Exploring the evidence from England and France. Child Youth Serv Rev.2011;33(12): 2504-2511. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.029

14. Thoburn J, Courtney ME. A guide through the knowledge base on children in out-of-home care.J Child Serv. 2011;6(4): 210-227. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17466661111190910

15. Fisher PA. Review: Adoption, fostering, and the needs of looked-after and adopted children. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2015;20(1): 5-12. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/camh.12084

16. Tarren-Sweeney M. The mental health of children in out-ofhome care. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(4): 345-349. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32830321fa

17. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Child protection Australia 2014–15. Child welfare series no. 63. Cat. no.CWS 57.Canberra: Australian Government; 2016

18. Webster D, Barth RP, Needell B. Placement stability for children in out-of-home care: A longitudinal analysis. Child Welfare. 2000;79(5): 614

19. James S, Landsverk J, Slymen DJ. Placement movement in out-of-home care: Patterns and predictors. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2004;26(2): 185-206. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.01.008

20. Tarren-Sweeney M, Hazell P. Mental health of children in foster and kinship care in New South Wales, Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42(3): 89-97. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00804.x

21. Fallesen P. Identifying divergent foster care careers for Danish children. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(11): 1860-1871.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.08.004

22. Berrick J. When children cannot remain home: Foster family care and kinship care. Future Child. 1998;8: 72-87

23. Mendes P, Snow PC, S Baidawi. Young people transitioning from out-of-home care in Victoria: Strengthening support services for dual clients of child protection and youth justice. Australian Social Work. 2014;67(1): 6-23. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2013.853197

24. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2011. Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2013

25. Paxman M, Tully L, Burke S, Watson J. Pathways of Care:Longitudinal study on children and young people in out-ofhome care in New South Wales. Family Matters. 2014;94: 15

26. Chugani HT, Behen ME, Muzik O, Juhász C, Nagy F,Chugani DC. Local brain functional activity following early deprivation: a study of postinstitutionalized Romanian orphans. Neuroimage 2001;14(6): 1290-1301. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2001.0917

27. Humphreys KL, Gleason MM, Drury SS, Miron D, Nelson CA,Fox NA, et al. Effects of institutional rearing and foster care on psychopathology at age 12 years in Romania: follow-up of an open, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry.2015;2(7): 625-634. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00095-4

28. Mitchell G. Children with Disabilities Using Child and Family Welfare Services. Melbourne: OzChild; 2013

29. Victorian State Government. Roadmap for Reform: Strong Families, Safe Children; 2016

30. Herrman H, Humphreys C, Halperin S, Monson K, Harvey C, Mihalopoulos C, et al. A controlled trial of implementing a complex mental health intervention for the carers of vulnerable young people living in out-of-home care: The ripple project. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1): 436. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1145-6

年轻人离开原生家庭后安置不稳定性及可能的心理健康影响

Rice S, Cotton S, Moeller-Saxone K, Mihalopoulos C, Magnus A, Harvey C, Humphreys C, Halperin S, Scheppokat A, Mcgorry P, Herrman H

收容照料、社区照料、寄养照料、青少年心理健康

Background:Young people in out-of-home care are more likely to experience poorer mental and physical health outcomes related to their peers. Stable care environments are essential for ameliorating impacts of disruptive early childhood experiences, including exposure to psychological trauma, abuse and neglect. At present there are very few high quality data regarding the placement stability history of young people in out-of-home care in Australia or other countries.

Objectives:To undertake the first systematic census of background, care type and placement stability characteristics of young people living in the out-of-home care sector in Australia.

Methods:Data was collected from four non-government child and adolescent community service organisations located across metropolitan Melbourne in 2014. The sample comprised 322 young people(females 52.8%), aged between 12 – 17 years (mean age=14.86 [SD=1.63] years).

Results: Most young people (64.3%) were in home-based care settings (i.e., foster care, therapeutic foster care, adolescent care program, kinship care, and lead tenant care), relative to residential care (35.7%).However, the proportion in residential care is very high in this age group when compared with all children in out-of-home care (5%). Mean age of first removal was 9 years (SD=4.54). No gender differences were observed for care type characteristics. Three quarters of the sample (76.9%) had a lifetime history of more than one placement in the out-of-home care system, with more than a third (36.5%) having experienced ≥5 lifetime placements. Relative to home-based care, young people in residential care experienced significantly greater placement instability (χ2=63.018, p<0.001).

Conclusions:Placement instability is common in the out-of-home care sector. Given stable care environments are required to ameliorate psychological trauma and health impacts associated with childhood maltreatment, well-designed intervention-based research is required to enable greater placement stability, including strengthening the therapeutic capacities of out-of-home carers of young people.

[Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2017;29(2): 85-94.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216090]

1Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, Melbourne, Australia

2Centre for Youth Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, Australia

3Orygen Youth Health, NorthWestern Mental Health, Melbourne Health, Melbourne, Australia

4Deakin Health Economics, Centre for Population Health Research, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, Geelong, Australia

5Psychosocial Research Centre, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Melbourne, Australia

6NorthWestern Mental Health, Melbourne, Australia

7Department of Social Work, The University of Melbourne, Australia

*correspondence: Professor Helen Herrman. Mailing address: The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health; Centre for Youth Mental Health,The University of Melbourne, 35 Poplar Road, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia. E-Mail: helen.herrman@orygen.org.au

背景:收容机构中的儿童青少年和同龄人相比可能存在较差的心身健康水平。稳定的机构照料环境对改善早期童年经历所致破坏性影响是非常重要的,童年经历包括心理创伤、虐待和忽视。目前,澳大利亚或其他国家很少有关收容机构中儿童青少年的安置稳定性高质量研究的数据。

目标:首次针对澳大利亚在收容机构生活中的儿童青少年进行系统的背景、照料类型、和安置稳定性特征的调查。

方法:2014年收集了墨尔本市区的四家民间儿童青少年社区服务机构的数据。样本包括322名年轻人(女性占52.8%),年龄在12 - 17岁之间[平均年龄=14.86,(SD = 1.63)年 ]。

结果:在收容机构中,相对于社区收容照料类型(35.7%),大多数年轻人(64.3%)是基于家庭养育照料模式(即寄养、治疗型寄养照料、青少年照料模式、亲属照料、以及认领照料)。然而,与所有收容照料的孩子相比,这个年龄组被社区收容比例是较高的(5%)。第一次被社区收容的平均年龄为9岁(SD= 4.54)。不同的照料类型均无性别差异。其中有248人(76.9%)曾在收容照料系统中有一个以上的安置场所,有117人(36.5%)经历了超过5个安置场所。相对于家庭养育照料者,社区收容的儿童青少年经历了更显著的安置不稳定性(χ2=63.018, p<0.001)。

结论:安置不稳定性在收容照料机构是常见的现象。需要一个稳定的照料环境来改善被虐待儿童所导致的心理创伤和健康影响。精心设计并以干预为基础的研究能够增加安置稳定性,包括强化对儿童青少年收容照料者的治疗能力。

Dr. Simon Rice obtained a combined Master of Psychology (Clinical) / PhD degree (5 years total) the School of Psychology, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, Australia in 2012. And he also completed a Grad.Cert. in Clinical Epidemiology (University of Newcastle, AUS) in 2014. He is currently working as a research fellow & clinical psychologist in the Centre for Youth Mental Health, the University of Melbourne. He is a board-approved supervisor and is also a clinician in the Youth Mood Clinic at Orygen Youth Health. He is a member of Australian Psychology Society and Early Career Advisory Group committee. He has both a clinical and research interest in mood disorders in young people, vulnerable populations and e-mental health interventions. His PhD focused on the assessment of depression in men, the key outcome of which was the Male Depression Risk Scale, a validated multidimensional screening tool for assessing externalizing symptoms associated with distress in men. He has been highly productive since graduating from his PhD, receiving a number of national and international competitive awards, >$2.5M AUD in research funding, and has published 46 peer reviewed papers.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

上海精神医学的其它文章

- Efficacy towards negative symptoms and safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment for patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review

- Factors related to acute anxiety and depression in inpatients with accidental orthopedic injuries

- A study of the characteristics of alexithymia and emotion regulation in patients with depression

- Efficacy and metabolic influence on blood-glucose and serum lipid of ziprasidone in the treatment of elderly patients with first-episode schizophrenia

- The current situations and needs of mental health in China

- Factitious disorder - A rare cause for unexplained epistaxis