机器人辅助单髁膝关节置换术的历史与未来

2017-09-26付君陈继营

付君 陈继营

. 专论 Special article .

机器人辅助单髁膝关节置换术的历史与未来

付君 陈继营

关节成形术,置换,膝;人工膝关节;机器人辅助手术

全球范围内每年行单髁膝关节置换术 ( unicompartmental knee arthroplasty,UKA ) 治疗终末期膝关节炎的患者高达数万例,尽管在假体设计、手术器械和术后康复等方面均有巨大提高,但是仍有大约 10% 的翻修率[1-2]。既往大量文献报道了假体位置不良可导致偏心负荷、磨损、不稳、无菌性松动和髌骨关节等问题,而截骨误差则是假体位置不良的重要影响因素[3-5]。因此,机器人辅助 UKA 的发展可极大提高术前计划、术中截骨和术后假体位置的精准性。现就机器人辅助 UKA 的历史回顾、技术简介、疗效以及未来展望问题综述如下。

一、历史回顾与技术简介

美国机器人协会对机器人的定义是:一种用于移动各种材料、零件、工具和专用装置的、用可重复编制的程序动作来执行各种任务的多功能操作机[6]。骨科手术机器人应用于临床始于 20 世纪 90 年代,由于当时设计上的缺陷,且与传统手术技术比较无明显的疗效优势,同时还存在一些机器人相关手术并发症,因此应用不是很广泛,最终被抛弃[7-9]。直到最近,由于适应证的扩展以及相关文献报道,越来越多地骨科医生开始关注并学习骨科机器人手术[10-13]。其中,用于 UKA 的比较成熟的机器人系统是 Navio PFS 和 Mako RIO ( 均通过了美国 FDA 的认证 )。

机器人手术系统大体上可以分为三类:被动、半自动和自动[14-15]。被动系统完成手术时必须有医生持续直接的控制操作,自动系统则不需要医生的直接干预,半自动系统 ( Navio PFS 和 Mako Rio ) 需要医生干预,但是可以通过触压觉反馈来提高医生的控制力和手术安全性。从理论上讲,这类系统可以通过限制截骨空间的深度来控制截骨量的多少[16-17]。

机器人辅助 UKA 的基本步骤包括:下肢 CT 扫描 ( 表1 )[18],机器人工作站中术前计划和虚拟植入假体,术中注册和手术计划再确认,完成截骨和植入假体。做术前计划时,需要将下肢三维 CT 扫描资料导入机器人工作站,利用其携带的软件术前可进行冠状面、矢状面和旋转的对线。首先,需要识别定位出一些解剖标志并确定机械轴和解剖轴,然后进行虚拟假体植入并确定假体型号,术中还可以根据图像和数据反馈对假体型号以及位置和方向进行调整,以最终确认手术计划。

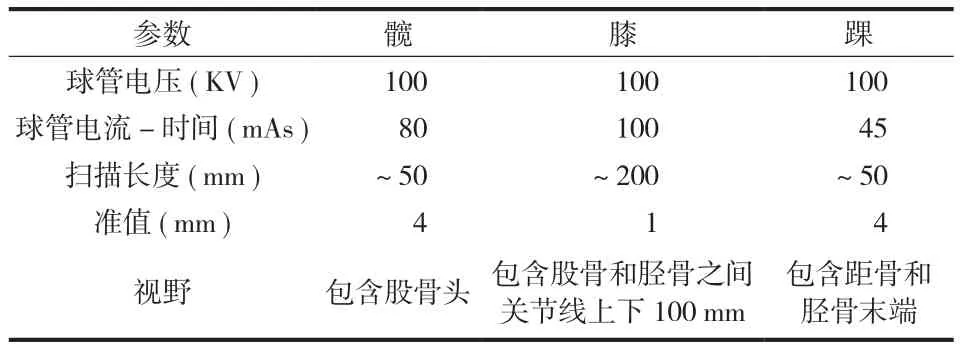

表1 机器人辅助 UKA 术前髋、膝、踝关节三维 CT 扫描成像方案Tab.1 Imaging protocols of 3 regions: hip, knee, and ankle before robot-assisted UKA

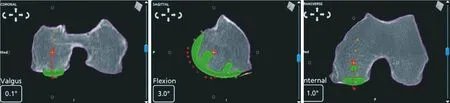

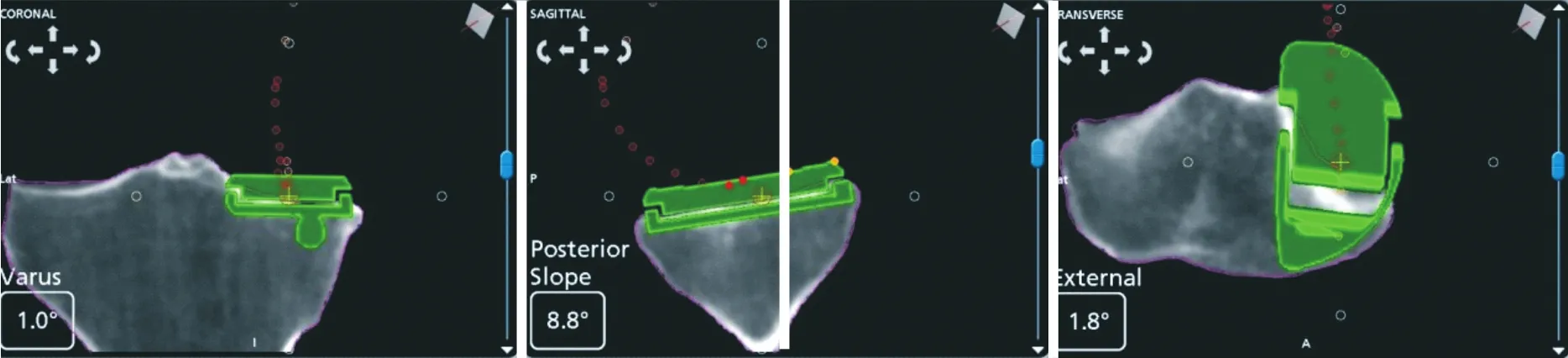

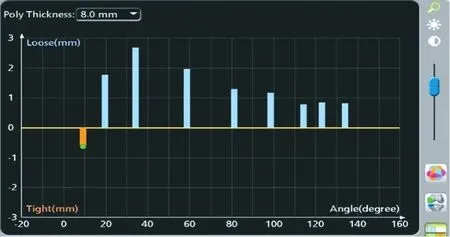

手术入路与传统 UKA 入路基本一致,切口长度可稍短 1~2 cm。手术过程中,首先需要将机器人导航模块和机械臂放置适合操作的位置,然后分别在胫骨和股骨上安装参考架,一步步完成股骨和胫骨的骨性标志的注册和定位,此时术前 3D 模型与膝关节真实解剖结构融合。此时,可根据软组织平衡张力图对假体位置进行调整,并最终确认假体的位置和术中计划,极大地提高了假体位置的精准性 ( 图1~3 )。

图1 术中计划 - 股骨假体内 / 外翻、屈 / 伸、内 / 外旋Fig.1 Intraoperative planning about varus / valgus, flexion / extension, and internal / external rotation of the femoral component

图2 术中计划 - 胫骨假体内 / 外翻、前 / 后倾、内 / 外旋Fig.2 Intraoperative planning about varus / valgus, anterior / posterior slope direction, and internal / external rotation of the tibial component

图3 机器人辅助 UKA 术中计划实时显示软组织平衡张力,横坐标:膝关节屈伸角度 ( ° ),纵坐标:松紧程度 ( mm )Fig.3 The real-time view of soft tissue balance during the operative planning in robot-assisted UKA. Horizontal axis: flexion and extension angle of the knee ( ° ); Vertical axis: level of tightness ( mm )

完成上述步骤以后,医生可以在准确的 3D 实时导航监测下进行股骨和胫骨的骨床打磨。打磨结束后,清理周围残余骨赘和软组织,安装试模,用探针检查其植入位置是否合适,取出试模植入假体,完成假体和衬垫安装后还可以进行运动力学分析,以初步判断患者术后的下肢力线和屈伸活动范围等。

二、疗效优势

既往大量研究报道 UKA 早期失败与假体位置植入技术误差有关,致使下肢力线偏差矫正过度或不足[19],UKA 术后力线偏差可能引起假体松动、过度磨损以及对侧间室病变加快进展。此外,胫骨假体后倾角过大可引起骨质应力增大、前交叉韧带撕裂和胫骨假体松动[20]。这些都促进了机器人辅助 UKA 技术的发展[21-22]。

早期机器人辅助 UKA 的证据均来源于体外试验,其结果显示胫骨和股骨假体的位置误差率降低[23-25]。Citak 等[26]在一项尸体研究中对比机器人 ( n = 6 ) 和传统技术 ( n = 6 ) 假体安放的准确性,发现股骨 ( 均方根误差:1.9 mm 和 3.7° vs. 5.4 mm 和 10.2° ) 和胫骨 ( 均方根误差:1.4 mm 和 5° vs. 5.7 mm 和 19.2° ) 假体位置准确性均有显著提高,而且这两种技术之间差异性如此之大,是不能忽略的。

最近,Lonner 等[27]在一项三级临床研究中对比了机器人辅助 ( n = 31 ) 和传统手工 ( n = 27 ) UKA的疗效,结果显示传统技术的胫骨后倾角变异性较高 ( 3.1° vs. 1.9°;P = 0.02 ),此外,胫骨假体在冠状面上对线的平均误差也较大 [ ( 2.7 ± 2.1 ) ° vs. ( 0.2 ± 1.8 ) °;P < 0.0001 ]。Pearle 等[28]在一项四级临床试验中评估了 10 例机器人辅助 UKA 的疗效,发现所有病例 ( 100% ) 的术前计划与术中胫骨、股骨冠状面对线的误差均在 1° 以内,而且术前设计与术后下肢全长测量的力线均方根误差为 0.24° ( 范围:0°~0.5° )。另外一篇文献报道了 50 例第一代 Mako RIO 辅助 UKA的术前计划和术后 X 线片测量结果的对比分析,发现胫骨和股骨假体位置误差均 < 1.5 mm 和 3°[29]。

还有作者研究了是否假体位置对线的提高能转变为临床功能疗效[30-32],Cobb 等[33]在一项随机对照试验中评估了 28 例机器人和传统 UKA 的术后疗效,结果显示所有 ( 100% ) 机器人辅助 UKA 患者术后对线偏差均在 2° 以内,而仅有 40% 的传统手术能达到上述标准。此外,他们还发现机器人辅助 UKA 组术后 KSS 评分较高 ( 65.2 ± 18 ) vs. ( 32.5 ± 28 )。

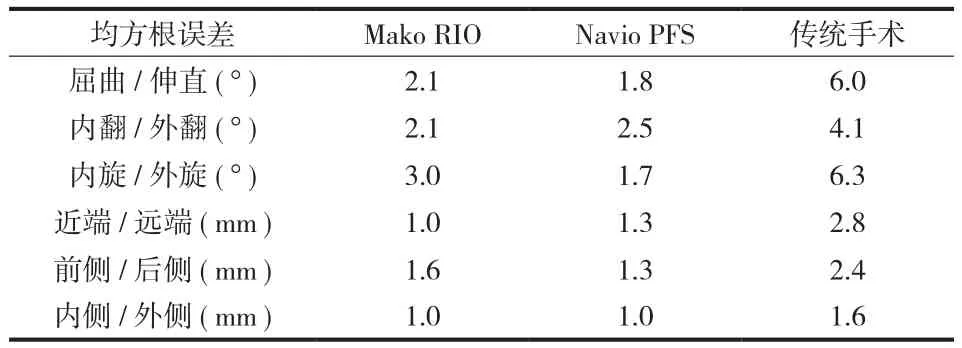

与传统 UKA 比较,机器人辅助 UKA 可在微创切口下完成所有操作,而且提高手术精准度。大量研究报道机器人辅助 UKA 极大地降低了假体位置的变异性和误差[29,34]( 表2 )。事实是无论该系统是否需要术前三维 CT 扫描或是不需要影像学支持,其精准度都很高[35-36]。此外,Plate 等[37]证实了机器人辅助 UKA 系统可以帮助医生精确地重复软组织平衡的计划,因此可以改善假体和下肢对线,他们还报道了最终的韧带平衡与术前计划相比可以精确到0.53 mm,大约 83% 的病例可在屈伸活动中保证1 mm 以内的平衡误差。

表2 假体位置误差 - 机器人辅助手术比传统手术Tab.2 Positioning error-Robot-assisted techniques vs. conventional techniques

评估一项新颖高级的手术技术时,必不可少的需要考虑其手术时间和学习曲线是否有增长,Karia 等[38]发现经验丰富的骨科医生在人造假骨上进行机器人辅助 UKA 时,其联合旋转和平移误差均比传统手术低。在学习过程中,虽然传统手术的手术时间要短,但是也存在着一些位置的不准确。从另一个角度来考虑,不论其学习经验如何,机器人辅助 UKA 可以使医生放置 UKA 假体时达到精准的位置。另外一个由 Coon 等[39]报道的研究称,与传统手术相比,Mako 系统辅助 UKA 有较短的学习曲线和较高准确度。一项前瞻性多中心观察研究评估了 11 名骨科医生用 Navio PFS 系统在尸体和假骨上训练一段时间后完成他们最初的临床病例手术时间,学习曲线显示仅需要 8 台手术即完成 95% 的全部学习并维持在一个稳定的手术时间[40]。

三、潜在问题

机器人辅助 UKA 有许多问题,选择该项技术时须权衡其潜在的优势与问题。机器人辅助 UKA 与传统UKA 相似的并发症包括:假体松动、聚乙烯磨损、对侧间室关节炎进展、感染、僵硬、不稳和血栓栓塞等,除此之外,限制机器人技术扩展最主要一大障碍是费用的增加[41]。这些机器人系统的购置和维护费用十分昂贵,而且还需要额外配备高级的 CT 机,投资回报率也是一大挑战[42]。Moschetti 等[41]对 Mako RIO 系统进行Markov 分析发现,假如系统成本是 136.2 万美元,那么在费用高于传统手术的同时因其带来较好的疗效还能创造一定的价值。然而,他们对 Mako RIO 系统进行分析估计,结果显示平均每例机器人辅助 UKA 的费用大约为 19 219 美元 ( 传统 UKA 为 16 476 美元 ),与 47 180 美元 / 质量调整生命年的费用相关。其研究结果还提示成本效益比与病例数量相关,超过 94 例 / 年则费用较低。也就是说,费用 ( 价值 ) 很大程度上取决于投资成本、年度服务费以及避免不必要的术前 CT 扫描[43]。

另一个问题是特殊的机器人相关手术风险,最显著的是术中固定参考架的骨针以及接收光学信号的参考点骨钉,额外增加了皮质骨的应力集中,有一定的骨折风险,此外在干骺端置入骨钉时上述问题更加明显。也有文献报道在进行截骨时有一定的软组织 ( 侧副韧带和切口皮肤 ) 损伤风险。

再者,术前进行的三维 CT 扫描增加了患者的放射风险。最近 Ponzio 和 Lonner[44]报道一次机器人辅助UKA 术前 CT 扫描 ( Mako RIO 成像方案 ) 的平均放射有效剂量是 4.8 mSv,相当于 48 次 X 线胸片透视的放射剂量。而且该研究中有至少 25% 的患者还进行其它类型的扫描,其中一些患者的放射总剂量高达 103 mSv。这些风险不能忽略,

因此 10 mSv 则可能增加一次患致命性癌症的可能性,而且相关文献报道在美国每年大约有 29 000 例额外的癌症与 CT 扫描有关[45-46]。然而,这些增加的放射风险也不完全都存在于机器人辅助 UKA 系统中,例如Navio PFS 则不需要 CT 扫描。

四、未来展望

当前骨科领域手术机器人的设计理念的重点是影像学结果的精准性,早期的一些研究结果证实能降低翻修率并提高功能疗效,未来革新将可能继续改进术前计划、机器装备以及术中工作流程,这些革新可能在某种程度上简化手术过程并缩短学习曲线。关键的领域包括术前分析、术中感应器和机器控制仪器。当前典型的术前计划需要术前放射学检查 ( CT 或 X 线片 ),通过注册解剖标志转为机器人注册空间并定义界限和手术计划,下一步的重点是无须进行放射学检查,以关节的运动学资料为主,术前计划将融合解剖与运动学的框架。此外,未来假体的设计也可能出现变化,一些公司已经在研发只有机器人辅助才能植入的 UKA 假体。总之,过去 10 多年医学技术的迅速发展导致骨科领域机器人手术技术的发展与革新,尤其是机器人辅助UKA。精确的假体位置、量化的软组织平衡以及完美的影像学对线都得到了极大改善,而且可重复率极高。未来还需要进一步评估对线和平衡的改善是否能影响临床功能和 ( 或 ) 假体生存率。

[1] Eickmann TH, Collier MB, Sukezaki F, et al. Survival of medial unicondylar arthroplasties placed by one surgeon 1984-1998[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2006, (452):143-149.

[2] Mariani EM, Bourne MH, Jackson RT, et al. Early failure of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty[J]. J Arthroplasty, 2007, 22(6 Suppl 2): S81-84.

[3] Moreland JR. Mechanisms of failure in total knee arthroplasty[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1988, (226):49-64.

[4] Liau JJ, Cheng CK, Huang CH, et al. The effect of malalignment on stresses in polyethylene component of total knee prostheses-a finite element analysis[J]. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon), 2002, 17(2):140-146.

[5] Malo M, Vince KG. The unstable patella after total knee arthroplasty: etiology, prevention, and management[J]. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2003, 11(5):364-371.

[6] Hockstein NG, Gourin CG, Faust RA, et al. A history of robots: from science fiction to surgical robotics[J]. J Robot Surg, 2007, 1(2):113-118.

[7] Siebert W, Mai S, Kober R, et al. Technique and first clinical results of robot-assisted total knee replacement[J]. Knee, 2002, 9(3):173-180.

[8] Honl M, Dierk O, Gauck C, et al. Comparison of robotic-assisted and manualimplantation of a primary total hip replacement: A prospective study[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2003, 85-A(8):1470-1478.

[9] Siebel T, Kafer W. Clinical outcome following robotic assisted versus conventional total hip arthroplasty: a controlled and prospective study of seventy-one patients[J]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb, 2005, 143(4):391-398.

[10] Cobb J, Henckel J, Gomes P, et al. Hands-on robotic unicompartmental knee replacement: a prospective, randomized controlled study of the acrobot system[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2006, 88(2):188-197.

[11] Cobb JP, Kannan V, Brust K, et al. Navigation reduces the learning curve in resurfacing total hip arthroplasty[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2007, (463):90-97.

[12] Davies BL, Rodriguez Y, Baena FM, et al. Robotic control in kneejoint replacement surgery[J]. Proc Inst Mech Eng H, 2007, 221(1):71-80.

[13] Rodriguez F, Harris S, Jakopec M, et al. Robotic clinical trials of uni-condylar arthroplasty[J]. Int J Med Robot, 2005, 1(4):20-28.

[14] Netravali NA, Shen F, Park Y, et al. A perspective on robotic assistance for Knee arthroplasty[J]. Adv Orthop, 2013, 2013:970703.

[15] Health Quality Ontario. Computer-assisted hip and knee arthroplasty. Navigation and active robotic systems: an evidence-based analysis[J]. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser, 2004, 4(2):1-39.

[16] Lang JE, Mannava S, Floyd AJ, et al. Robotic systems in orthopaedic surgery[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2011, 93(10):1296-1299.

[17] Davey SM, Craven MP, Meenan BJ, et al. Surgeon opinion on new technologies in orthopaedic surgery[J]. J Med Eng Technol, 2011, 35(3-4): 139-148.

[18] Bell SW, Anthony I, Jones B, et al. Improved accuracy of component positioning with robotic-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty:Data from a prospective, randomized controlled study[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2016, 98(8):627-635.

[19] Collier MB, Eickmann TH, Sukezaki F, et al. Patient, implant, and Alignmentfactors associated with revision of medial compartmentunicondylar arthroplasty[J]. J Arthroplasty, 2006, 21(6 Suppl 2):S108-115.

[20] Hernigou P, Deschamps G. Posterior slope of the tibial implant and the outcome of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2004, 86-A(3):506-511.

[21] Roche M. Robotic-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: the MAKO experience[J]. Clin Sports Med, 2014, 33(1):123-132.

[22] Kianmajd B, Carter D, Soshi M. A novel toolpath force prediction algorithm using CAM volumetric data for optimizing robotic arthroplasty[J]. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg, 2016, 11(10):1871-1880.

[23] Watanabe T, Abbasi AZ, Conditt MA, et al. In vivo kinematics of a robot-assisted uni- and multi-compartmental knee arthroplasty[J]. J Orthop Sci, 2014, 19(4):552-557.

[24] Moon YW, Ha CW, Do KH, et al. Comparison of robot-assisted and conventional total knee arthroplasty: a controlled cadaver study using multiparameter quantitative three-dimensional CT assessment of alignment[J]. Comput Aided Surg, 2012, 17(2):86-95.

[25] Smith JR, Riches PE, Rowe PJ. Accuracy of a freehand sculpting tool for unicondylar knee replacement[J]. Int J Med Robot, 2014, 10(2): 162-169.

[26] Citak M, Suero EM, Dunbar NJ, et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: is robotic technology more accurate than conventional technique[J]. Knee, 2013, 20(4):268-271.

[27] Lonner JH, John TK, Conditt MA. Robotic arm-assisted UKA improves tibial component alignment: a pilot study[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2010, 468(1):141-146.

[28] Pearle AD, O’Loughlin PF, Kendoff DO. Robot-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty[J]. J Arthroplasty, 2010, 25(2):230-237.

[29] Dunbar NJ, Roche MW, Park BH, et al. Accuracy of dynamic tactile-guidedunicompartmental knee arthroplasty[J]. J Arthroplasty, 2012, 27(5):803-808.e1.

[30] Turktas U, Piskin A, Poehling GG. Short-term outcomes of robotically assisted patello-femoral arthroplasty[J]. Int Orthop, 2016, 40(5): 919-924.

[31] Clark TC, Schmidt FH. Robot-assisted navigation versus computer-assisted navigation in primary total knee arthroplasty: Efficiency and accuracy[J]. ISRN Orthop, 2013, 2013:794827.

[32] Luites JW, Wymenga AB, Blankevoort L, et al. Accuracy of a computer-assisted planning and placement system for anatomical femoral tunnel positioning in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction[J]. Int J Med Robot, 2014, 10(4):438-446.

[33] Cobb J, Henckel J, Gomes P, et al. Hands-on robotic unicompartmental knee replacement: a prospective, randomized controlled study of the Acrobot system[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2006, 88(2):188-197.

[34] Lonner JH, Smith JR, Picard F, et al. High degree of accuracy of a novel image-free handheld robot for unicondylar knee arthroplasty in a cadaveric study[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2015, 473(1):206-212.

[35] Jaffry Z, Masjedi M, Clarke S, et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasties: robot vs. patient specific instrumentation[J]. Knee, 2014, 21(2): 428-434.

[36] Yen PL, Chu YJ, Hsu SW, et al. Coordinated control of bone cutting for a CT-free navigation robotic system in total knee arthroplasty[J]. Int J Med Robot, 2014, 10(2):180-186.

[37] Plate JF, Mofidi A, Mannava S, et al. Achieving accurate ligament balancing using robotic-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty[J]. Adv Orthop, 2013, 2013:837167.

[38] Karia M, Masjedi M, Andrews B, et al. Robotic assistance enables inexperienced surgeons to perform unicompartmental knee arthroplasties on dry bone models with accuracy superior to conventional methods[J]. Adv Orthop, 2013, 2013:481039.

[39] Coon TM. Integrating robotic technology into the operating room[J]. Am J Orthop, 2009, 38(2 Suppl):S7-9.

[40] Wallace D, Gregori A, Picard F, et al. The learning curve of a novel handheld robotic system for unicondylar knee arthroplasty. Paper presented at: 14th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Computer Assisted Orthopaedic Surgery[C]. 2014, 18-21.

[41] Moschetti WE, Konopka JF, Rubash HE, et al. Can robot-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty be cost-effective? A Markov decision analysis[J]. J Arthroplasty, 2016, 31(4):759-765.

[42] Swank ML, Alkire M, Conditt M, et al. Technology and cost-effectiveness in knee arthroplasty: computer navigation and robotics[J]. Am J Orthop, 2009, 38(2 Suppl):S32-36.

[43] Lonner JH. Robotically assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty with a handheld image-free sculpting tool[J]. Orthop Clin North Am, 2016, 47(1):29-40.

[44] Ponzio DY, Lonner JH. Preoperative mapping in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty using computed tomography scans is associated with radiation exposure and carries high cost[J]. J Arthroplasty, 2015, 30(6):964-967.

[45] Costello JE, Cecava ND, Tucker JE, et al. CT radiation dose: current controversies and dose reduction strategies[J]. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2013, 201(6):1283-1290.

[46] Berrington de González A, Mahesh M, Kim KP, et al. Projected cancer risks from computed tomographic scans performed in the United States in 2007[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2009, 169(22):2071-2077.

Research progress on robotic-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty

FU Jun, CHEN Ji-ying. Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital, Beijing, 100853, China

Robotic-assisted orthopedic surgery has been introduced to improve the accuracy of preoperative planning, operative bone cuts, component implantation position, and soft tissue balance in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty ( UKA ), with the expectation of improvement in implant durability and survivorship. Currently, roughly one-fifth of UKAs in the US are being performed with robotic assistance, and it is anticipated that there will be a substantial growth in market penetration of robotics over the next decade. First-generation robotic technology improved substantially implant position accuracy compared to conventional methods; however, high capital costs, uncertainty regarding the value of advanced technologies, and the need for preoperative computed tomography ( CT ) scans are barriers to its broader adoption. Newer image-free robotic-assisted orthopedic surgery optimizes both implant position accuracy and soft tissue balance, without the need for preoperative CT scans. Its portability makes it suitable for the application in an ambulatory surgery center, where approximately 40% of these systems are currently being utilized. There are a few reports about clinical outcomes and long-term follow-up results, however, it remains unknown whether more accurate component position brings better clinical effects or better long-term survival rate of the implants. This article will review the robotic experience for UKA, including history, rationale, system descriptions, outcomes and future innovations.

Arthroplasty, replacement, knee; Knee prosthesis; Robotic-assisted surgery

CHEN Ji-ying, Email: chenjiying_301@163.com.

10.3969/j.issn.2095-252X.2017.09.002

R687.4

解放军总医院转化医学重点项目 ( 2016TM-004 )

100853 北京,解放军总医院骨科

陈继营,Email: chenjiying_301@163.com

2017-02-21 )

( 本文编辑:李贵存 )