圩田景观:荷兰低地的风景园林

2017-01-13作者荷兰斯蒂芬奈豪斯

作者:(荷兰)斯蒂芬·奈豪斯

翻译: 韩冰

校对: 郭巍

Text: Steffen Nijhuis (The Netherlands)

Translator: HAN Bing

Proofreading: GUO Wei

圩田景观:荷兰低地的风景园林

作者:(荷兰)斯蒂芬·奈豪斯

翻译: 韩冰

校对: 郭巍

Text: Steffen Nijhuis (The Netherlands)

Translator: HAN Bing

Proofreading: GUO Wei

荷兰低地大部分都是圩田,人们通过人工控制水位,可以在圩田中工作和生活。人与水之间数百年来此消彼长的相互作用孕育了丰富多样的圩田景观。地质上底层土壤的差异、水与土的动态变化以及人类干预过程生成了种类繁多的圩田形式。本研究从风景园林的视角系统地探索了荷兰圩田景观形态塑造的成就,并将其视觉化呈现。圩田,不仅仅可以看作水力学现象的产物,同时也是空间结构和文化表达的结果:圩田景观不仅仅可观、可游,同时反映了荷兰文化。通过探索圩田景观形态,我们可以“解读”荷兰低地的场地精神,以便获取其后隐藏的信息及设计知识,并成为下一步发展的线索。本研究分两个阶段分析了圩田景观的风景园林化形式,并借助系统分析和制图的方式呈现了圩田景观的共通点和差异性。首先,调研所有圩田并进行数字化,得到第一张系统化的荷兰圩田地图。而地理信息系统(GIS)的运用不仅仅保证了精确度,也为使得将信息融入地图并组建空间数据库成为可能。在第二个阶段,进一步研究圩田这一低地基本景观单元。通过对选定的不同圩田类型(海岸黏土圩田、河流圩田、湖床圩田、和泥炭土圩田)的实例进行形态学分析,列举并解读每一种圩田类型的特征。截至目前,圩田景观的研究大多基于自然和历史地理学角度,而上述分析使得人们可以触及圩田景观的空间设计法则,并得到这类景观保护和转型的线索。

圩田景观;设计分析;荷兰低地;形式分析;类型学;图术

韩冰/女/1991年/山东人/硕士生/ 北京林业大学园林学院(北京 100083)

Translator:

Han Bing was born in 1991,native of Shangdong province. She is a postgraduate of Landscape Architecture School in Beijing Forestry University.(Beijing 100083)

校对简介:

郭巍/1976 年生/男/浙江人/ 博士/ 北京林业大学园林学院副教授/ 荷兰代尔伏特理工大学(TUD)访问学者/研究方向为乡土景观(北京 100083)

Proofreader:

GUO Wei, who was born in 1976 in Zhejiang, obtained his PHD degree in 2008. Now, he is an associate professor in School of Landscape Architecture, Beijing Forestry

University and a visiting scholar of Delft University of

Technology, the Netherlands. His major focuses on vernacular landscape.

1 导论

圩田分布于世界各处沿海和冲积形成的低地上。人们控制这些垦地的水位,并在其上工作和生活。人与水之间此消彼长的相互作用持续了约数个世纪之久,孕育出丰富的圩田景观。然而,气候变化和经济发展使圩田景观受到威胁。随着海平面上升而日益增长的洪水威胁、大规模排水导致的持续沉降以及急速的城市化,应对这些变化并做到有规划地发展迫在眉睫。为了保护这一珍贵文化遗产,我们需要收集相关经验和知识,来找寻保护这种景观和引导其转型的线索。将圩田看作是一种水力学现象或历史过程产物的研究有大量,但很少有研究将圩田看作一种空间结构和文化表达的结果:圩田景观不仅仅是可观可游的,同时也是文化的展示[1]。为了填补这一研究领域的空白,代尔夫特理工大学(荷兰)的风景园林团队展开了一个长期研究项目,重点从风景园林层面来研究圩田景观。这个项目除扩充知识,还促进了对于这类具有人文意义但又水害频发的低地景观的关注度提升,也使人们意识到过度耕种及大量建设的现状问题。同时,该项目也为政策制定以及如何从风景园林角度进行规划和设计提供了参考。本研究强调圩田景观是一种文化的表达——而不是单纯水利工程的产物——并借助图术、案例研究以及比较研究的方式,推断和解读这些“圩田景观(polderscapes)”的异同点。研究主要成果有《海的土地》(2007),其研究重点为湖床圩田;《荷兰圩田地图集》(2009),从更宽泛的角度叙述圩田;以及《综合性荷兰圩田地图册》(2013),是针对荷兰圩田的首次系统性综述[2]。此外还有近来酝酿的以国际视角研究圩田的《世界圩田景观》。

本文旨在从风景园林角度,概述荷兰圩田景观的研究。这项研究理清了圩田背景的发展脉络,系统研究并描绘了多种尺度下的圩田景观丰富性,完成了基于GIS的覆盖国土面积的地图绘制,并在代表案例研究的基础上,对不同圩田类型的特征进行了描述。文章的开头概述了作为一种文化产物的荷兰圩田景观。接下来则是研究策略的介绍,详尽说明了如何运用形态研究及地图作为可视化思维和交流的工具。因此,本文在讨论荷兰圩田地图的绘制过程时,重点叙述了其主要信息来源以及圩田单元的识别。接下来,则重点说明在研究单个圩田特征时采用的分析框架,并列举荷兰一处17世纪的湖床圩田贝姆斯特尔圩田(Beemster)为例。最后,在文章的末尾给出结论。

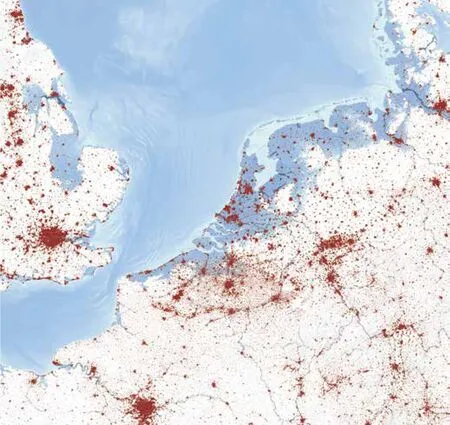

1 欧洲西北部的荷兰低地(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)The Dutch lowlands in Northwest Europe (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

2 作为文化产物的荷兰圩田景观

圩田景观可以被定义为:“一处平坦的区域,最初面临高水位的威胁(来自地表水或地下水的永久或季节性的威胁)。在围垦后,这一区域能够独立调控水位,并由此与其原来所处的水文状况隔离开来[3]。因而,衍生的圩田景观是一种文化和历史表达结果,因当地自然环境、知识技术与管理之间的相互作用而产生。” 这个概念涵盖了门类纷繁的圩田景观,包括长期处于积水环境下的泥塘沼泽、浅海和湖床地区,以及暂时受到水涝和积水影响的浅潮低地及冲积平原。基于上述水环境的区别,可以总结出3类圩田景观:(1)低洼地围垦产生的圩田景观,(2)开垦近海产生的圩田景观,及(3)湖泊排水后产生的圩田景观[4]。尽管这些圩田景观有一定范围的一致性,但由于地质上底层土壤、水与土的动态变化以及人类干预过程的差异,因而在世界范围内,圩田的形式极为多变。虽然自然条件是形成差异的重要因素,但人类在圩田发展过程中也起到决定性的作用。这是因为景观是人类与自然因素相互作用的结果。正如地理学家卡尔·索尔(Carl Sauer)所说:“文化是催化剂,自然是媒介,形成的文化景观就是结果。”[5]

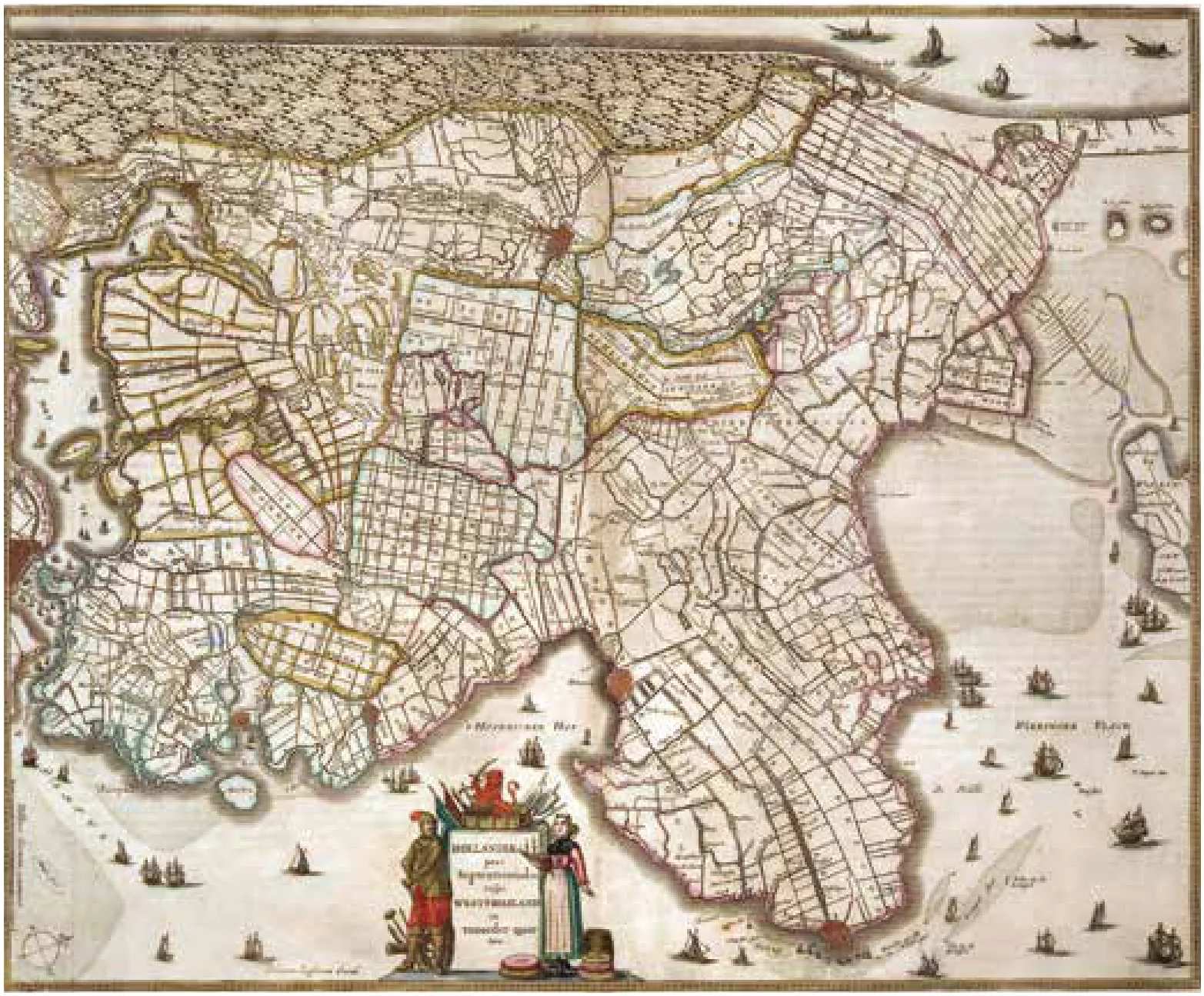

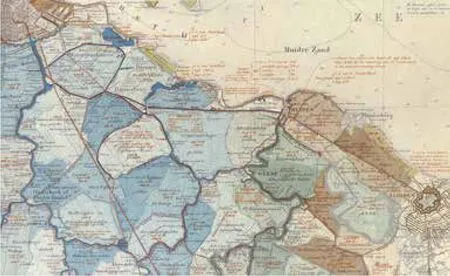

2 作为花园的荷兰:Joan Blaeu绘制的十七世纪地图,显示出了荷兰的北荷兰省几何式的圩田结构(代尔夫特理工大学图书馆,Tresor提供)Holland as Garden: seventeenth century map by Joan Blaeu showing the geometrical polder landscape of North Holland, the Netherlands (TU Delft Library, Tresor)

3作为圩田的花园:奥兰治王室的Honselaarsdijk王室花园成为了荷兰园林的代表,见Abraham Bega和Abraham Blooteling于1683年描绘的示意图。(皇家档案馆提供)The garden as polder: the princely garden of Honselaarsdijk became a representation of the Garden of Holland with the House of Orange as its protector as depicted by Abraham Bega and Abraham Blooteling, 1683 (Royal Archive)

2.1土地的测量、开垦及划分

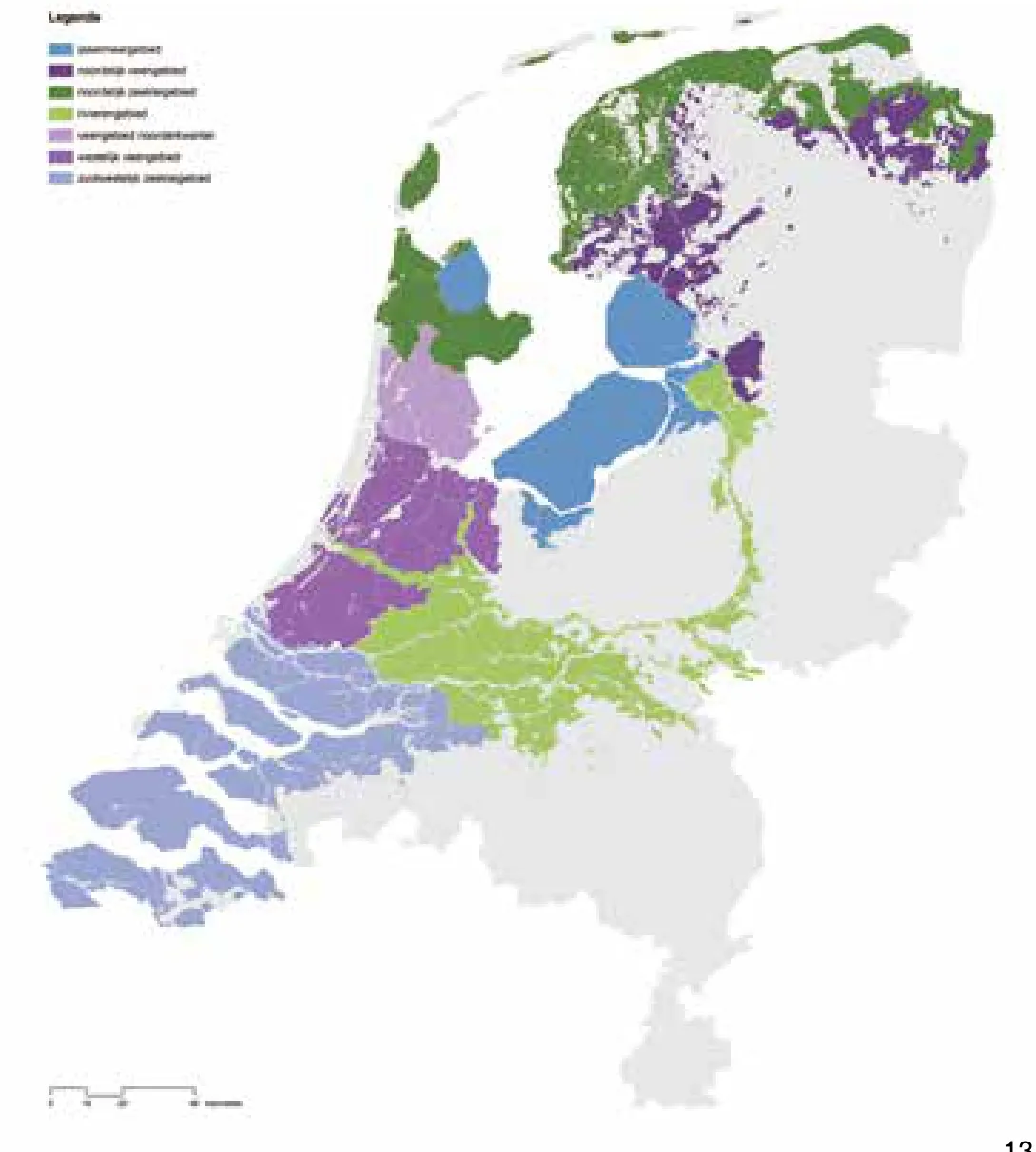

在荷兰的莱茵河、默兹河及斯凯尔特河的三角洲地带(图1),生产性圩田景观有十分悠久的规划、建造及维护的历史。圩田景观源远流长,与荷兰文化融合共生。从自然角度上来看,这一点也毋庸置疑,因为圩田占据荷兰国土面积的一半,另从生产知识和水资源管理角度来看也解释得通。诸如大堤、水坝和涵洞等最古老的水利基础设施,最早可以追溯到罗马之前的时代。但直至公元1世纪罗马人迁入后,才开始大规模泥炭沼泽的开垦[6]。随后于10世纪开始了对荷兰其余的泥炭沼泽进行系统性开垦。16世纪的工程、测量及制图领域的发展也为土地开垦注入了新的动力。堤坝建设的进步(约1576年)以及风车排水的运用(自1533年开始)使得围湖造田成为可能。同样,16世纪30年代发明了三角测量法,土地测绘师开始使用测量链和罗盘进行更大范围区域的测量,误差也减少了[7]。测量师开始绘制地图,用于土地清算、分割(设计布局)、对地块进行管理及优化等,因而他们在堤坝建设、水利施工以及大型土地开垦项目中起到至关重要的角色。随着资本主义的兴起,土地在当时成为一种商品,因此地图也成为具有法律效应的工具。地图是植根于公民美德与区域开垦的社会面貌的表征[8]。

发展建设和耕作的需求潜力使湖床圩田的实现在经济上成为可能。富有的商人不断投资大型项目,开垦出肥沃土地将粮食供给城市,并建设远离城市污染的舒适的居住区域。湖泊转化和开垦成可盈利的耕地,在其上建造美丽的庄园和赚钱的牧场。截至17世纪40年代,阿姆斯特丹土地面积相比16世纪增长了40%。这要归功于贝姆斯特尔(Beemster)(1608-1612)、普梅尔(Purmer)(1662)、沃尔默(Wormer)(1625)以及斯荷尔姆(Schermer)(1631)四处湖床圩田的开垦。圩田布局由测量师决定,他们都接受过土地测量和制图绘图的规范训练。圩田布局并非是单一的设计结果,而是结合了土地分割的实用性。土地被分割成为不同尺度的矩形块,与各处的土壤组成、水利工程设施及土地利用最优化等相适应,最终形成多层格网结构。借鉴几个世纪以来累积的经验,测量员能够轻松地应用灵活多变的方格来处理场地环境[9]。西蒙·斯蒂文(Simon Stevin)(1548-1620)是荷兰城市规划、聚落和防御工事建设的奠基人。他深谙这些原则,并将这种灵活而世俗化的规划实践总结成文。其中多层格网的对称性、轴线组织方式以及其灵活的矩形模数体系也可以应用在城市规划之中[10]。

2.2荷兰作为花园

土地开垦、耕作和创造这种典型的几何景观成为了荷兰造园艺术发展的基础,以至于国家本身也被认为是一个花园而人民则是园丁:荷兰作为花园或者Hortus Batavus(图2)[11]。由17世纪土地开垦和测量技术形成的线性模式将开垦的土地转化为真正意义上的文化景观,人们在其中出于经营获利和美化目的而建造了乡村田庄[12]。这些田庄附属花园的几何秩序完美融合了圩田景观的规则线性[13]。其中一例是腓特烈·亨利(Frederik Hendrik)(1584-1647)在洪塞拉尔戴克(Honselaarsdijk)的皇家花园。该花园后来成为了荷兰式园林的代表,归属奥兰治王室(the House of Orange)(图3)[14]。与其他许多田庄类似,洪塞拉尔戴克融入了周边的圩田景观,局部与特有地形条件吻合,并借鉴了土地开垦及分割的常用手段。因而,它是实用性和舒适感的融合,象征了人类对自然的优化和改造:这个花园就是一处圩田,并且是荷兰作为花园这一壮阔环境中的一部分。

16及17世纪是荷兰文化形态形成的关键时期。围垦过程作为一种政治、经济和制图共同作用下的文化产物形式。圩田景观的规则化布局与现代观念中关乎文明、所有权和治国方略的方面不谋而合。尽管“圩田(polder)”这一术语起源于荷兰(17世纪:“polre”),但这并不意味是荷兰人最先开始营造类似景观的。自公元前3 000多年前的人类文明曙光开始,在美索不达米亚地区,人们已懂得利用水土环境营造生产性景观,并修建了用水基础设施,来抵御洪水(堤坝及水坝)并管理用水(排水或灌溉)[15]。然而,在16和17世纪,荷兰形成了开垦圩田的理念。圩田成为一种国家象征,体现了荷兰人在努力驯服水土自然时的坚强意志和技术特长。同时,垦田行动也似乎成为了一种荷兰出口产品,影响了从12世纪直到目前欧洲范围内甚至世界其他区域的圩田营造[16]。

今天的荷兰圩田景观正经历向多功能空间的转型。除了农业属性外,人们越来越多地看重圩田景观的休闲观光、自然保护与蓄水、房屋建设等功能。这些发展为维持空间质量及乡村景观特性带来了压力。而解决这些空间问题的关键,则隐含在圩田景观自身所蕴含的丰富形式之中。

3 理解圩田景观

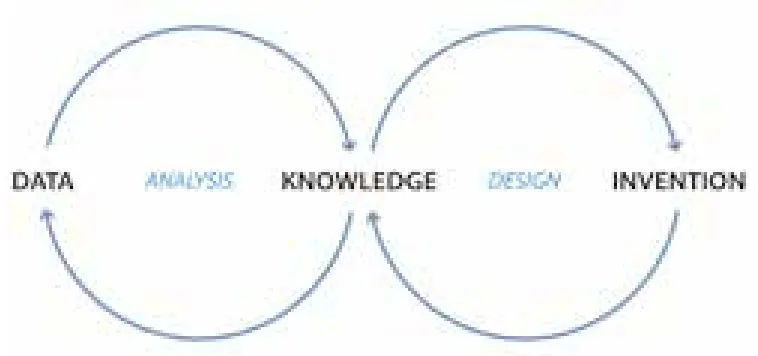

4 地图在知识积累和设计形成循环中起到了推动和媒介作用:一个从数据到知识经验,从知识经验引导创新的自我循环过程(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)Maps as facilitator and mediator in the knowledge formation-cycle and design generation-cycle: an iterative process from data to knowledge, from knowledge to invention (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

形态学研究被用于荷兰圩田景观的研究中。通过探寻圩田景观蕴含的形态学,可以“解读出”荷兰低地的场地精神,由此可以获取其中隐含的信息和设计要点,作为探究未来发展的线索。事实证明形态研究,或称形式研究是有意义的,因外在形态可作为解读和分析景观的媒介。自然、生物和社会文化的作用力因其效果明显,也成为研究的重点所在。形式分析属于一种解释性研究手段(也可以称其为:阐释学)。通过形式分析及对景观可视化表达形式的解读来获取相关信息。我们可将形式看作一个纯粹的没有预先设定意义的解释系统,因而根据假说推断结论的程度便降至最低[17]。这一类研究的目的不仅仅是为了了解和研究景观建筑,同时也侧重于探索其空间智慧,提升理解和设计其空间组成的能力,以及找寻不同尺度之间的联系。形态学研究有三个特征[18]。首先,包含所有尺度的景观,从花园尺度到区域性尺度。第二,将景观结构的立体特征与其空间及动态的模式结合起来。第三,形态学研究的方法关注这种形态是如何形成的。因为景观是时间的产物——时间上经历了概念的形成、发展以及突变。此外,形态学研究也同样应用于在城市设计、建筑、艺术与地理学领域[19]。

在景观形态的研究中,地图被看做发掘信息的基础性工具。几个世纪以来,人们借助地图这一工具描绘和了解景观。地图帮助人们理解人类社会或自然世界中的一些事物、概念、情形、过程或事件[20]。地图中蕴含了大量信息,且十分具有说服力,因而是获取知识的重要手段。这种手段应该与被定义为图术(Mapping)的手法区分来,图术是通过整理空间信息而获取知识的手段。它是一个过程,而不是一项既成成品。图术需要制图探索活动,利用地图图纸本身以及地图绘制作为中介来视觉化建构和传达空间信息。因而可以说,图术并不完全与现存环境一一对应,故需要对其包含的信息进行解读和重构。图术需要通过理性和系统的方法“消化”信息,因而这是一个个人过程,受到个体选择和判断或称视觉思维的影响。与此同时,视觉的呈现有助于信息传播,表达出其中的关系、结构和模式,亦即视觉传达。对地图的详细研究、比较研究以及地图叠加分析都是有用的分析方法[21]。这些探索有助于风景园林研究人员获得其中未知或潜在的信息,是获取空间知识并指导设计过程的基础。研究地图同样有助于数据的解读,从中可以总结出知识经验,启发设计灵感(图4)。

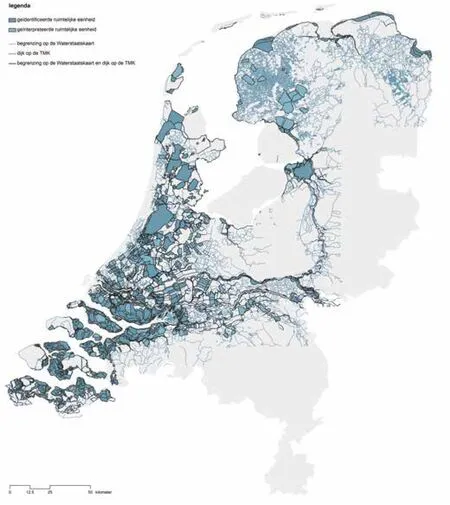

5 综合性荷兰圩田地图(S. Nijhuis 及M.T. Pouderoijen提供,代尔夫特理工大学)Comprehensive polder map of the Netherlands (S. Nijhuis & M.T. Pouderoijen, TU Delft)

6 早期圩田地图的案例,由Floris Balthasars在1611年绘制,范围是代尔夫特及其周边地区(国家档案馆提供)Example of an early polder map in the surroundings of Delft made by Floris Balthasars, 1611 (National Archive)

研究者分两步对圩田景观的形态进行分析,通过系统分析和制图来揭示其异同。首先,对所有圩田进行测量,将成果数字化,获得第一张综合性的荷兰圩田地图。第二,将圩田看作基本景观单元进行进一步研究。

4 综合性的荷兰圩田地图

7 地形军事地图1850-1864(TMK)的细部(代尔夫特理工大学图书馆,Tresor提供)Detail of the Topographic and Military Map 1850-1864 (TMK) (TU Delft Library, Tresor)

8 水利地图第一版1865-1891的细部(代尔夫特理工大学图书馆,Tresor提供)Detail of the Hydraulic Map first edition 1865-1891 (TU Delft Library, Tresor)

9高度精确的现代荷兰高程图(AHN5)细部(M.T.Pouderoijen提供,代尔夫特理工大学图书馆)Detail of the highly accurate Height map of the Netherlands, AHN5 (M.T. Pouderoijen, TU Delft)

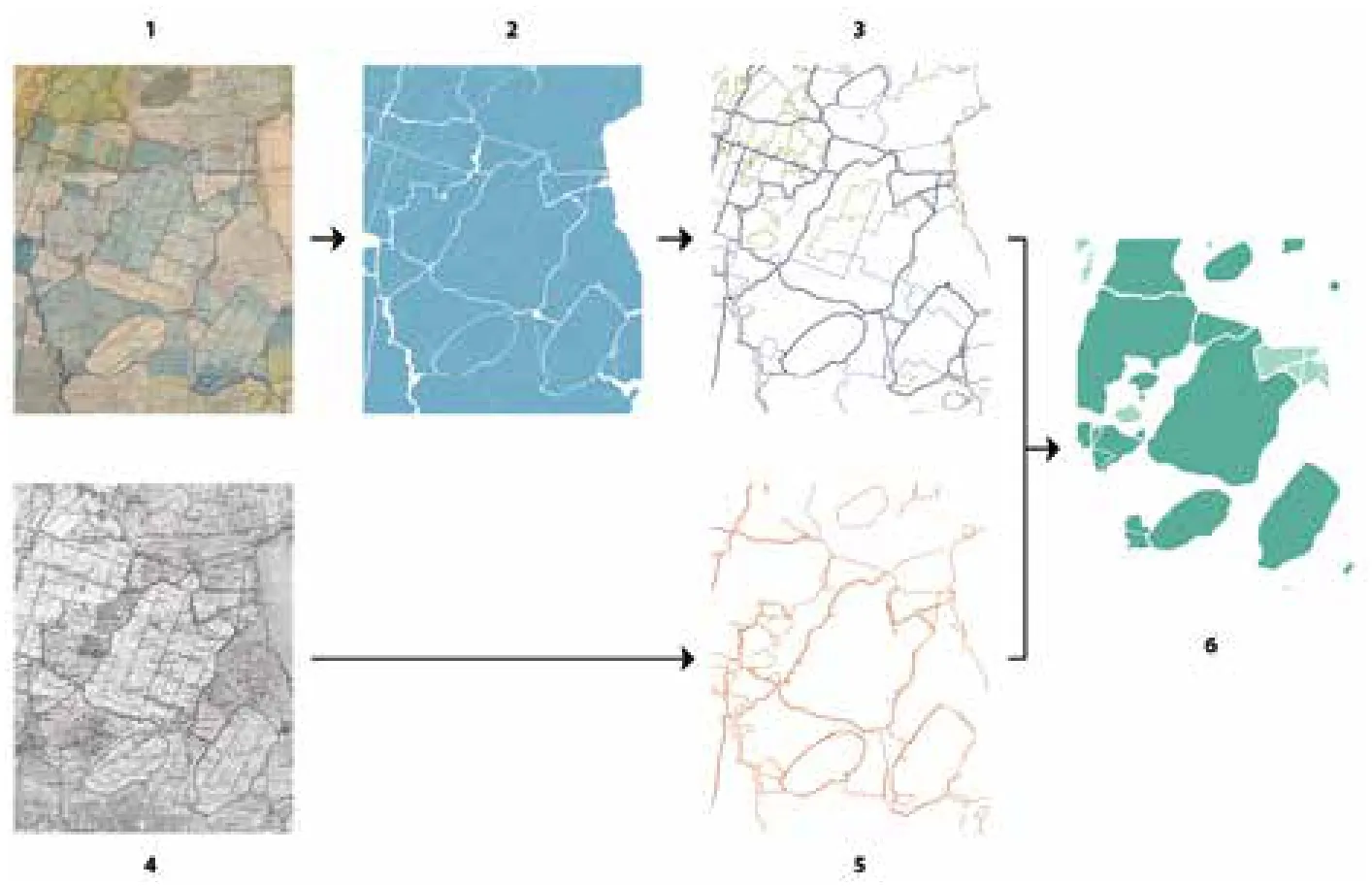

10 圩田景观的系统性描述过程:(1)对水管理地图进行数字化/地理信息校准处理,(2)水管理单元矢量化,(3)边界的确定,(4)对地形及军事地图数字化/地理信息校准处理,(5)堤坝的矢量图示化,(6)评估与整合(S. Nijhuis 及 M.T. Pouderoijen提供,代尔夫特理工大学)Systematic delineation of the polder landscape: (1) digitized/geo-rectified water management map, (2) vectorization water management units, (3) definition boundaries, (4) digitized/geo-rectified topographic & military map, (5) vectorization dikes, (6) evaluation and integration (S. Nijhuis & M.T. Pouderoijen, TU Delft)

荷兰的圩田地图系统地呈现了丰富多样的圩田景观形式(图5)。从某种意义上说,它的独特性主要在可将整个荷兰圩田景观包括在内,且对圩田这种水利和景观实体再加以突出。尽管荷兰圩田制图学历史悠久,但水委会(waterboards)留存的地图多描绘单个圩田或圩田的一块局部区域,并没有全国范围的圩田地图(图6)。书籍中经常出现对圩田景观的描述,但主要是从水管理和历史意义的角度。1884年A.A. Beekman出版了《圩田上的荷兰》。本书为荷兰圩田的概念描述打下了科学基础。后继者追随他的脚步,眼光更多投向了特定区域圩田或湖床圩田。这张综合性的荷兰圩田地图首次尝试绘制整个国土范围的圩田,并将圩田作为一种水利营建和景观结构。深刻理解圩田这一属性,对于解读这种独特的空间形态来说是必要的。而在覆盖全国的这份圩田地图中可以找到这一联系,因而可以说圩田地图是带领荷兰圩田制图方面向前迈进的一步[22]。

自20世纪伊始,由于爆发式的城市化和经济发展,荷兰景观发生了很大改变,因而几乎不可能通过当代的地形地图来辨认出圩田单元,尤其是历史较长的那些。为了解决这一问题,研究者重点考虑将现存完好的景观与可获取的详细地图资料结合起来。收集的19世纪至20世纪间的历史地图为拼凑一张完整的圩田地图提供了可能。这一时期的城市——也有例外的情况——外围的古代防御工事依旧完好。景观则形成于先前的几个世纪,且其状态大多数情况下并没有改变。19世纪的测量术已经有很高的精确度,因而那个年代的地图图像投射在现在的地图上,也不会有太多出入。这一时期同样开始了覆盖全国的1850定位。地图经过扫描后,转存为像素构成的数字文件。每一张数字地图都运用了地理信息系统(GIS)手段进行了地理修正和地理坐标定位。由此,对历史地图的平面进行了调整,并参考荷兰的标准坐标系系统进行扩充[23]。这使得地图得以精确地合并转换为地理坐标信息。

下一步则是对地图的解读。将圩田识别为空间水利景观单元,并将其矢量化(图10)。参考荷兰高程图评估和修正所绘制的地图,同时将1850年后开垦的地块鉴别出来。得到的成果是一张基于GIS的荷兰圩田地图,展示了尺度在1:10 000至1:25 000不等约9 087个圩田单位,其中包括了圩田的各种类型:低地围垦、围海以及垦湖得到的圩田。更具体地说,这张地图展示了水利单元及其明确的边界。圩田在这一框架结构中作为空间单元存在。

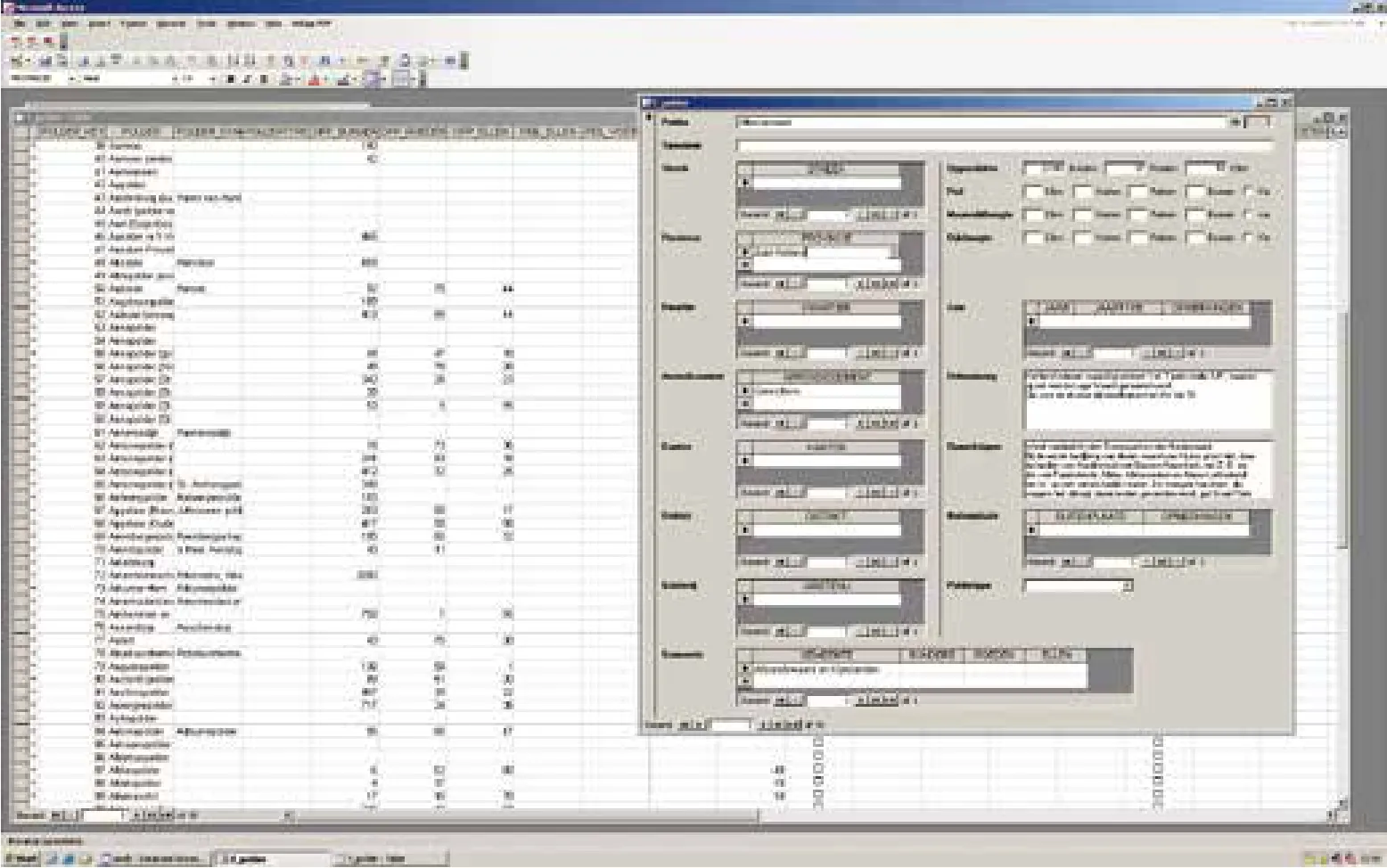

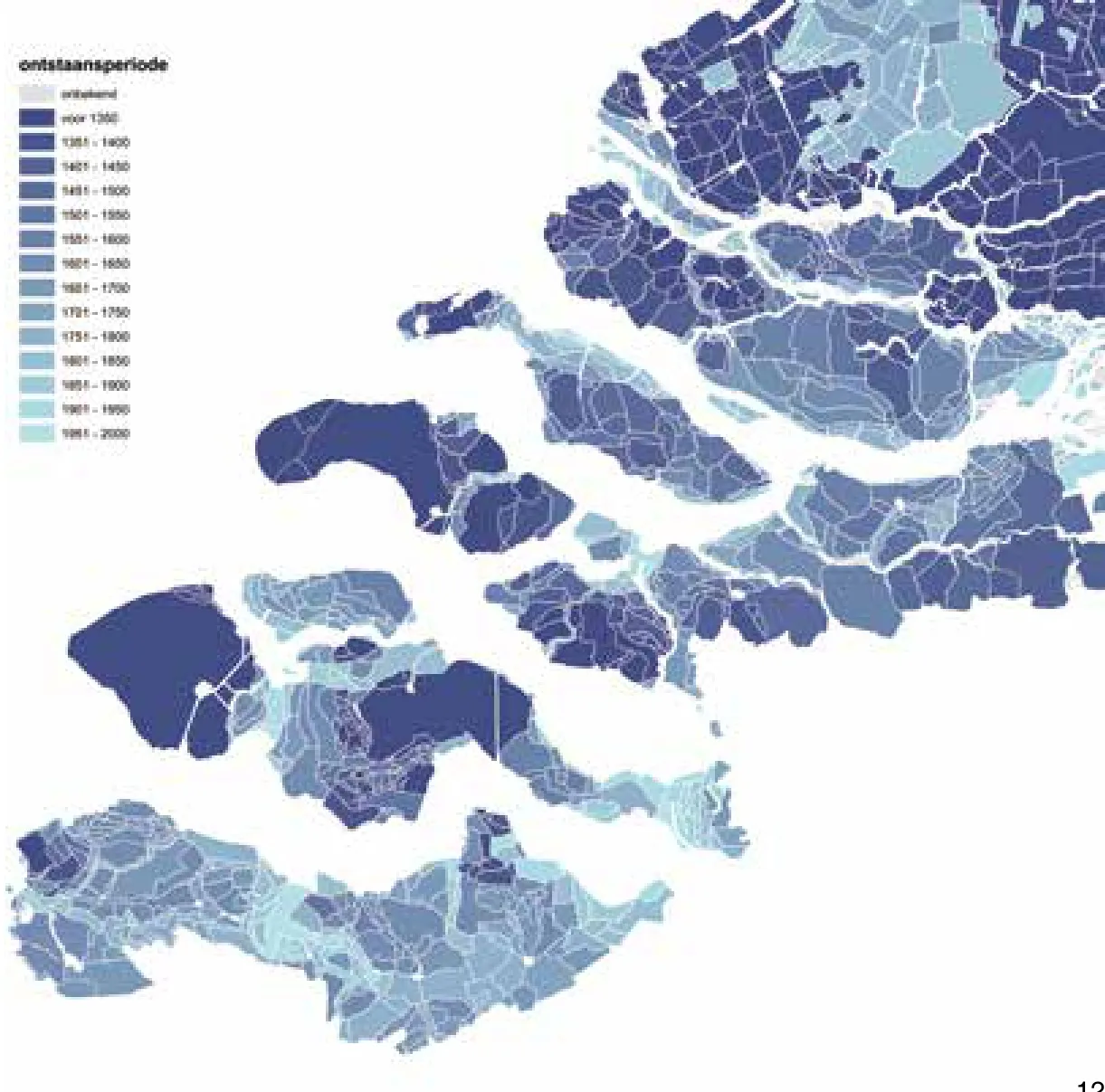

GIS的运用不仅保证了工作的精确度,同样也使地图链接信息成为可能,地图转变为空间数据库,包含了:名称、开垦年代、数据资料等等。研究人员参考荷兰地理字典(Geographical Dictionary of the Netherlands)(Van der Aa,1839-1851,荷兰语),创立了一处字典中提及的所有圩田的数据库(图11)。这些信息恰好可以与地形军事地图-(TMK)和水利地图中的数据相互补充及核对。可以运用GIS空间化这些信息,进行分析和视觉化。同样,它可以为研究圩田景观随时间的发展提供支持(图12),也可用于对圩田特性的计算分析如:圩田尺度、形式复杂度及圩田形态。1864地形军事地图(TMK)以及1865-1891水利地图第一版的绘制,两张图纸的比例都是1:50 000(图7-8)。这两张类似的历史地图成为了绘制圩田地图的基础。接下来,借助机载激光雷达点云数据(每平方米约8个点位)绘制出高度精确的现代荷兰高程图(AHN5),这样可以确保范围的精确并借此识别新生圩田(1850年以后开垦的圩田)(图9)。

11 圩田数据库截图(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)Screenshot of the polder database (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

绘制圩田地图的第一步是对1850-1864地形军事地图(TMK)以及1865-1891第一版水利地图, 共计366张地图进行数字化及地理坐标

为了把握圩田形式多样性的关键,研究人员基于其自然地理特性来解读圩田地图。不同的特性来自于基质(岩石及地形)、土壤和水力学方面的差异。人类活动的影响也是其中的一个因素。因此,在非生物因素和人类活动间的相互作用下,结果会出现有代表性的几种特性的特定组合。因此形成了基于自然地理景观的圩田类型学,每一种类型都有许多突出的形态特征(图13)。圩田的类型包括:海洋黏土圩田(例如Tzummerpolder)、泥炭土圩田(例如Ronde Hoep)、河流圩田(例如Alblasserwaard)以及艾塞尔湖周边圩田(例如Noordoostpolder)。因为湖床圩田(例如Beemster贝姆斯特尔圩田)同样是从泥炭土湖泊开垦形成的,因此可以看做泥炭土圩田的一个子类型。

5 圩田语法的识别

12 圩田地图细部,展示了西南部圩田景观的发展过程(M.T. Pouderoijen提供,代尔夫特理工大学)Detail of the polder map showing the development of the polder landscape in southwest (M.T. Pouderoijen, TU Delft)

13 基于自然地理景观的几种圩田类型(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)Polder typology based on physical-geographical landscapes (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

14 选取的圩田是荷兰种类繁多圩田景观的代表(从左到右): Noordoostpolder,Tzummerpolder,Polder Biesbosch,Kockengen(Paul Paris摄)The selected polders represent the wide variety of polder landscapes of the Netherlands(from left to right): Noordoostpolder , Tzummerpolder, Polder Biesbosch , Kockengen (Paul Paris)

每一处圩田都可以看作具备自己特征的独特景观单元,如同一个个小块的镶嵌物,一齐拼成了整个荷兰圩田景观马赛克。深刻理解圩田单元的独特形式,可以让我们了解其模式、形态学及视觉特型的复杂性——由此可以总结荷兰低地的特征。在进行形态分析时,选取了17个代表性的圩田单元进行深入分析,以识别其圩田语法或空间句法。圩田语法指的是一套决定其空间组成的结构规律和原则。理解圩田语法是引导相关景观转型,或是叠加新设计于其上的起点。所选取的圩田能够代表多样的圩田类型,并覆盖了荷兰低地的不同自然地理区域,同样也涉及到不同的围垦时期(图14)。

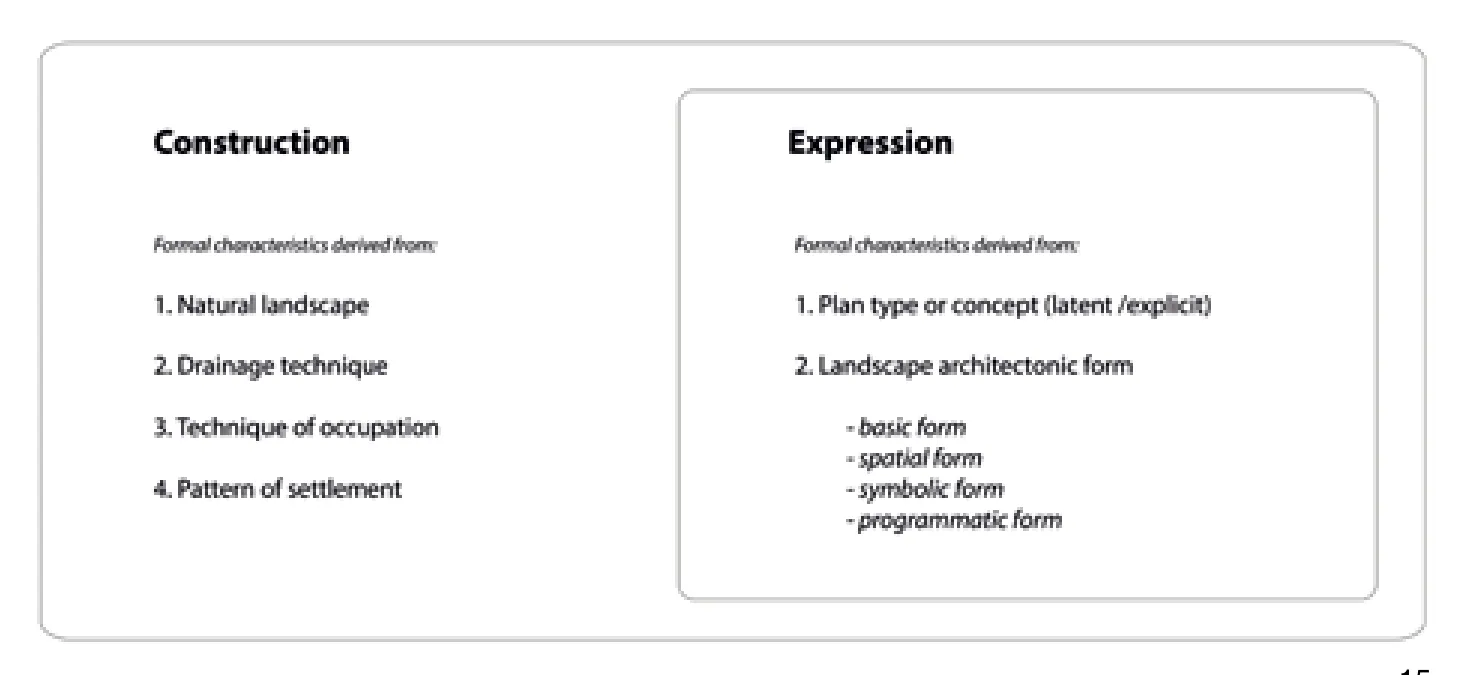

5.1分析框架

15 识别圩田语法的分析框架(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)Analytical framework for the identification of the polder grammar (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

16 北荷兰省的贝姆斯特尔湖床圩田(Paul Paris摄)The Beemster lakebedpolder in North Holland (Paul Paris)

17 约1300年的自然景观(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)The natural landscape around 1300 (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

在介绍每一个圩田单元时,首先描述其自然环境和历史背景,之后对其进行详细分析并说明其圩田语法。为了识别圩田语法,需要分析圩田形式的结构特征和表现特征(图15)。结构特征指的是在自然景观向可居留可开发的农业景观转型过程中形式上表现的特征。表现特征指的是圩田隐含的及表现出来的视觉和形式要素,这些要素促使圩田开垦过程中应用组合的、美学的和文化的主题。由此我们可以将圩田单元理解成为分层的实体,定义这一实体的则是最底层的自然景观、进一步进行的水利干预、以及有组织的土地农业开发。三者都在形式上烙下了印记。对于这种复杂分层的识别和描述关乎问题处理,因而十分重要,可以用于解决可能存在的技术和景观规划上的问题,诸如在水管理和城市化方面的问题。因此,也可以获取如何进一步开发圩田的线索。

在解读与结构特征相关的形式系统时,对每一块所选圩田的下述几方面进行了系统分析并加以视觉化表达[24]。

(1)自然形式特征:自然地理位置;土壤格局、地势、自然水系形式以及自然边界或轮廓;(2)水利形式特征:堤坝形式、排水沟渠、排水运河及大型水道的模式、蓄水渠系统、泵水系统以及水管理单元;(3)农耕形式特征:地块分布规律以及开发整地过程、地块分割形式以及路网模式;(4)聚落形式特征:农舍-农庄-地块之间的关系以及聚落的形式和分布。

研究与表现相关的特征时则分析了下述几个方面:(1) 组织模式、规划类型或概念;(2)风景园林化的形式:基础的、空间的、象征性的和程序化的形式。

在发现和描述圩田的景观特征过程中,历史地图、新绘制的地图及照片是重要工具。在介绍每一处圩田单元时,首先描述其自然环境和历史背景,之后进一步绘制基于调研的详细地图,包括圩田的自然景观、地形高度、水系统、基本形式和空间形式等。

5.2以贝姆斯特圩田( Beemster)为例

18 高程示意图(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)Height map (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

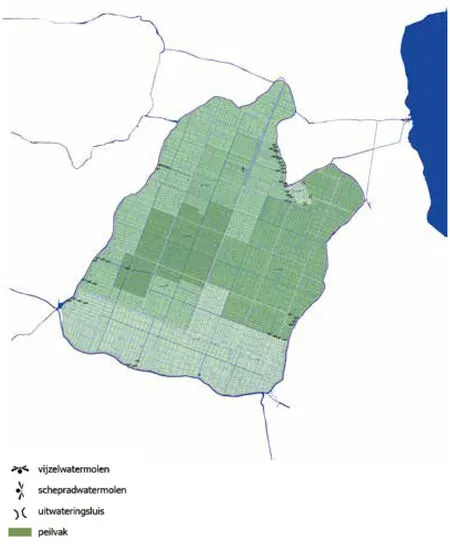

19 约1900年时贝姆斯特尔的水管理情况(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)The water management of the Beemster, around 1900 (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

下面将以贝姆斯特尔圩田作为例,对于这一框架的应用进行说明(图16)[25]。范围约72km2的贝姆斯特尔湖,是17世纪阿姆斯特丹北部陆地开垦活动中围垦的一系列湖泊中面积最大的[26]。公元1608至1612年,阿姆斯特丹富商对贝姆斯特尔湖床圩田投资进行开垦。因为众多原因,人们对其赞不绝口:作为治水成就,它宣告了荷兰人征服自然的能力,它是精妙技术和强大组织的产物,是农耕富足的良田,是浸润着建筑和园艺之美的知识宝库[27]。在这处湖床圩田中,人与景观的关系展现在其构筑系统的理性的尺寸和比例中。然而其组织形式并非单纯从功能和可持续角度出发,也有着美学的吸引力。这一圩田在1999年被联合国教科文组织收入了世界遗产名录。

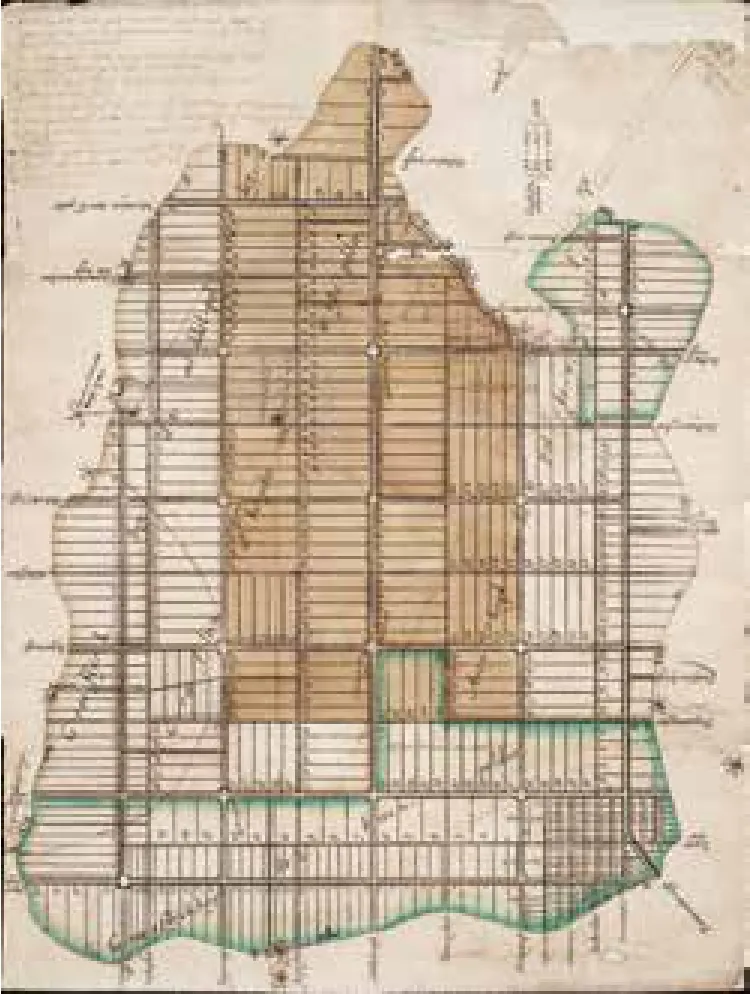

从自然形式特征来看,贝姆斯特尔圩田的轮廓直接源于一个自然泥炭湖泊,这个泥炭湖泊由先前的泥炭景观排水后形成的沼泽河流侵蚀而成(图17)。地表高程约为海平面海拔(ASL)之下1.9m至4m不等(图18)。风车、环状水渠以及围合堤坝构成其水利形式重要特征。最初圩田中架设43座风车,分3步将水泵入环状水渠中(图19)。现如今少数几个电泵就能替代它们。圩田细分为4个水管理单元,每个单元的海拔不同,并与湖底的自然地势相融合。四周则围有约42km的环状水渠(蓄水渠系统的一部分)以及堤坝。圩田地块分割的模数系统决定了其农耕形式特征。土地测量员Lucas Jansz Sinck (未知- 1622)完成了它的设计布局(图20)。经过几次修改后,最终版的格网由5-6条道路和4-5条水渠构成,交点间距离约为1 880m。“标准地块”是地块分割的最小单元,尺寸约为185×940m(图21)。地块的上端常常连接道路,终端则靠近排水渠。5个标准地块合并,形成了约940×940m的方形结构,方形的两边是排水渠,另外两边则是道路。4个这样的方形合并构成“贝姆斯特正方形”,四周是林荫路与十字交叉的沟渠。路网模式的规律性在当时有一定的实用性,采用尽可能多地修路的方式来延续交通,因而路网保持通畅。土地主人被授予“种植权利”,因此他们自行出资,沿着内部堤肩及自有土地前道路种植成排树木,形成了现有的典型封闭式景观空间(图22-23)。在聚落形式方面,北荷兰的施托尔普农舍(stolp)是贝姆斯特尔垦田农舍的典型,农舍附有农场,四周是树林带。贝姆斯特尔的一些施托尔普式农舍被称为“绅士农场”。尹荷恩农舍(the Eenhoorn)(1682)是现存的一处实例(图24)。这一农舍因其代表性的对称式正立面而闻名。建筑师Philips Vingboons(1607-1678)设计了这一高大的正立面,有一极具表现力的中部,在其上冠以颈状山墙。另有约50处乡村庄园,现多已不存。虽然对建筑的排列方式有相关规定,但可以对格网系统进行灵活多变的调整,因此网格也具有层次[28]。林荫路、空间、村庄、规划广场、乡村庄园、农场、水道以及风车结合为整体,形成了贝姆斯特尔的景观新类型。这种类型影射出了荷兰景观及城市以理性方式彼此联系的意向。圩田是自然、健康和生活幸福的荷兰理念的象征,也代表了新荷兰共和国的和平和富饶。同时圩田也因其拥有的田野的肥沃、乡村庄园的舒适及花园设计的优美而饱受赞誉[29]。模块式的方形和谐地融入了圩田之中,它们的反复出现,创造出区域无限大的幻觉。自然形式就其本身而言并不占据主导。例如其边界,边界仅仅存在于林荫路系统的地平线中,因而并不明显。因此荷兰低地的三维性、无限平面的错觉以及规律性的完美分割,是圩田最为重要的特性,也最容易遭到破坏。

20 贝姆斯特尔的地块分割地图,由Lucas Jansz Sinck于1612年绘制(Westfries档案馆提供)Parcellation map for the Beemster by Lucas Jansz Sinck, 1612 (Westfries Archive)

21 贝姆斯特尔的基本形式(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)The basic form of the Beemster (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

贝姆斯特尔圩田的实例证明,我们可以运用这种分析框架来研究圩田形式的结构特征和表现特征,也就是圩田语法。在每一处圩田之上,随着其圩田语法的应用与经营,呈现出特殊的形式。圩田具备独特个性和景观特点,其场地精神也得以展现。在这些形式特征的基础之上,可以从空间和时间方面来对不同的圩田单元进行比较。基于圩田的地理位置以及开垦方式,可以识别出其空间上的类似之处,时间方面则是通过开垦时期来比较。通过这种比较可以总结出一系列不同的圩田类型。其中一些是基于其自然、水利、聚落和农业形式,另一些则是基于其风景园林学特性。这些类型揭示出,在相关技术及设计手法的运用下,逐渐形成的圩田景观的共同特性及其发展历程。

圩田语法不仅仅是从风景园林层面理解圩田景观的工具,同样也是未来发展的基石。通过开展基于圩田语法的设计实验,我们可以探讨圩田景观的哪些要素可以转型以及其如何转型,同样也可以研究采用什么样的形式可以与经济和气候变化相适应。风景园林设计实验——通过设计的研究(research by design)——有助于探寻空间发展的可能性,诱导针对现有设计难题的解决措施及方案的生成[30]。这一类基于设计的知识经验可以导向新型圩田景观的形成,这种景观均衡连贯,并具有自己独特的特性和空间品质。

22 空间形式(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)The spatial form (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

23 贝姆斯特尔的一处典型的林荫道(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)A typical alee in the Beemster (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

24 尹荷恩农舍(the Eenhoorn)(1682)因其代表性的对称式正立面而闻名,带有高大、极具表现力的中部,在其上冠以颈状山墙(S. Nijhuis提供,代尔夫特理工大学)The Eenhoorn (1682) is renowned for its representative, symmetrical front fa?ade with its tall, expressive central section, crowned with a neck-gable (S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

6 结论

圩田景观是变化中的景观。有些变化影响深刻,有时则不那么剧烈。应该将圩田景观理解为一个动态的系统,这个系统受到自然过程和社会需求的影响而不断发生变化。自然景观由地质过程形成,并没有受到人类的干扰。在开垦、定居和对运用技术改造自然景观的过程中,文化景观渐渐形成。因此,圩田是几种条件相互作用的结果,其中包括自然景观条件、开垦水管理技术经验的可能性以及社会文化背景。同样,圩田景观是一种分层实体,时间的痕迹层层覆盖。其相似点不断累积,差异也不断扩大,因而形成了多种多样的圩田景观,其中每一种都拥有独特个性。然而,圩田景观依旧很容易受到影响。由于城市飞速发展以及自身功能的转变等,这些乡村景观通常遭受地平统一倾向及地块标准化的不利影响,因而丧失了其文化特性。因此,我们有必要从风景园林的视角解读这些景观,以从中提取隐含的相关知识和设计经验,并以正确的方式加以运用。

本文中呈现出了一种理解圩田景观一致性和差异性的特别方式,通过系统化描述和空间设计原则识别,为空间规划设计提供线索。在荷兰,完成了首份综合性荷兰圩田地图的绘制。这张地图同样也划定了一项“基准”,这一基准不仅可以指导圩田景观的历史重建,也拓宽了当下眼界和未来视角。此外,进一步研究将圩田作为低地的基础景观单元研究。对选定圩田案例进行类型学分析,并分别列举和解读了不同圩田类型(海洋黏土圩田、河流圩田、湖床圩田以及泥炭土圩田)的特性。尽管荷兰圩田是研究的核心,但这一研究原则在全球背景下均适用。本研究方法论体现了风景园林研究的典型思考方式,这种方式具备以下三个特征:首先,以多尺度的研究手法,将全部的圩田土地囊括在内,同时也通过圩田语法识别的方式,重点研究单个圩田。第二,研究将空间可视结构与水管理模式结合起来。第三,以有形的形-态为媒介,将圩田看作自然、生物和社会文化作用力共同作用的结果来研究。截至现在,研究人员仅仅是从水管理和历史角度出发对圩田景观进行探讨,而这样的分析可以使我们理解圩田的空间设计原则,并获得圩田保护及转型的启示。

1 INTRODUCTION

Polders can be found in coastal and alluvial lowlands all over the world. In these reclaimed areas water levels are artificially controlled so people can live and work there. This often centuries-old interaction between man and water has produced a rich variety of polder landscapes. These landscapes are under threat due to climate and economic change. Increasing flood risk due to sea level rise, ongoing subsidence due to intense drainage, and rapid urbanization ask for action to guide these developments. These valuable cultural heritage landscapes must be safeguarded through knowledge development providing clues for preservation and transformation. Though there are many studies on the polder as hydraulic or historic phenomenon, there are hardly any who address polders as spatial constructions and cultural expressions: the polder landscape as one can see and experience it, and also as a display of cultural aspects.1To fill this gap the Chair group Landscape Architecture at Delft University of Technology (Netherlands) initiated a long term research program with the focus on the landscape architecture of polder landscapes. This program aims to develop knowledge and raise awareness of these cultural flood-prone lowland landscapes and their problematic situation of intensive cultivation and habitation, while providing clues for policy making, planning and design from a landscape architecture perspective. The research addresses polder landscapes as cultural expressions-rather than only as results of water engineering-employing mapping, case studies and comparative research as means to understand the similarities and differences of these 'polderscapes'. Key results include Sea of Land (2007), with the emphasis on lakebed polders, The Polder Atlas of the Netherlands (2009), providing a more inclusive perspective on polders, and the Comprehensive Polder Map of the Netherlands (2013), the first systematic overview of polders in the Netherlands.2Polder landscapes of the world is a recent initiative that researches polder landscapes from an international perspective.

This article aims to provide a state of the art overview of the landscape architecture research on the Dutch polder landscape. It elaborates on the methodical backgrounds and offers insight in the systematic exploration and delineation of the wealth in polderscapes throughout the scales that resulted in a GIS-based country covering map and the characterization of polder types based on representative case studies. The article starts with introducing the Dutch polder landscape as a cultural product. Next, the research strategy is introduced elaborating on morphological research and maps as tools for visual thinking and communication. Consequently, the construction of the polder map of the Netherlands will be discussed addressing the main sources and the identification of polder units. The next section addresses the analytical framework for exploring the characteristics of individual polders, which is illustrated by an application on the Beemster, an example of a seventeenth century lakebed polder in the Netherlands. The article closes with some concluding remarks.

2 THE DUTCH POLDER LANDSCAPE AS CULTURAL PRODUCT

A polder landscape can be defined as: “A level area, in its origin subject to high water levels (permanently or seasonally, originating from either ground water or surface water), but that through impoldering is separated from its hydrological regime in such a way that a certain level of independent control of its water table can be realized.3As such the resulting polder landscape is a cultural-historical expression of the local interaction between physical conditions, knowledge and management." This definition includes a wide range of polder landscapes in areas where waterlogging or inundation occurs permanently, such as: fens and bogs, shallow sea and lake beds, or temporarily, such as tidal lowlands and river plains. Based on this distinction three groups of polder landscapes can be identified: (1) impoldered low-lying lands, (2) lands reclaimed from the sea, and (3) drained lakes.4Though there is a certain similarity in these polder landscapes, there is a great variety in polder forms caused by differences in the geological subsoil, the dynamics of water and land and human intervention across the world. Though physical conditions are an important factor for these landscapes, also humans play a decisive role in their development since landscapes are the result of the action and interaction of human and natural factors. As the geographer Carl Sauer stated: “Culture is the agent, the natural area is the medium, the cultural landscape is the result."5

2.1Surveying, reclaiming and dividing territories

There is a long tradition of designing, building and maintaining productive polder landscapes in the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt delta located in the Netherlands (Fig. 1). Polder landscapes are inherently part of the Dutch culture and have along history. In physical terms, since almost half of the country consists of polders, but also in terms of knowledge production and water management. Here the oldest water infrastructures such as dikes, dams and culverts date from pre-Roman times, but it was not until after the arrival of the Romans in the first century AD that large scale reclamations of peat fens and bogs took place.6Later, from the tenth century onwards the rest of the Dutch peat lands were systematically reclaimed. In the sixteenth century technological advances in engineering, surveying and cartography gave a new impetus to land reclamation. Not only advances in dike building (ca. 1576) and the application of windmills for pumping water (from 1533 onwards) made it possible to reclaim land from lakes. But also the invention of triangulation in the 1530s and the use of the measuring chain and compass made it possible for land surveyors to survey larger areas without too much distortion.7Surveyors also started to make maps for inventorying, land division (design of layouts), land management or improvement of land and therefore played an crucial role in dike building, hydraulic works and large land reclamation projects. In that time period maps also became legal tools as land became a commodity with the emergence of capitalism. Maps as representation helped to create an image of community built on civic virtue and territorial reclamation.8

The potential for building and farming made lakebed polders economically desirable. Wealthy merchants invested in these vast projects for the creation of fertile land to provide food for the cities and to create pleasant areas to live avoiding the pollution of the cities. Lakes had to be transformed and cultivated into a practical economic environment, with beautiful estates and profitable husbandry. By 1640, Amsterdam had forty percent more land than in the sixteenth century land due to lakebed polders such as the Beemster (1608-1612), Purmer (1622), Wormer (1625) and Schermer (1631). The layout of these polders was determined by surveyors that were trained in practical methods for land surveying, mapping and drawing. The polder layout was not the result of a single design, but emerged from a practical division of land in multi-layered grids of suitable rectangular blocks that adapted to the local soil composition, hydraulic engineering, optimal land use, etc. These surveyors built on centuries of experience with the application of various and flexible types of grids that could be adapted easily to local circumstances.9Simon Stevin (1548-1620), who stood at the basis of Dutch theories of urban planning, settlements and fortifications, adapted these principles and codified flexible and temporal planning applications of these multi-layered grids with symmetry, axial organization, and modular systems of rectangles for urban development.10

2.2Garden of Holland

Land reclamation, cultivation and the creation of this typical geometrical landscape lay at the foundation of the art of gardening in Holland, so much that the country itself became identified with the garden and its people with gardeners: the Garden of Holland or Hortus Batavus (Fig. 2).11The rectilinear patterns created by the seventeenth century reclamation techniques and land surveying turned reclaimed land into a truly cultural landscape in which country estates were built for profit and ornament.12The geometric order of their accompanying gardens fitted perfectly into the regular lines of the polder landscape.13This may be exemplified by the royal garden of Frederik Hendrik (1584-1647) at Honselaarsdijk. This garden became a representation of the Garden of Holland with the House of Orange as its protector (Fig. 3).14Honselaarsdijk was, as many other estates, integrated in the surrounding polder landscape, carefully adjusting to specific topographic conditions and employing common methods of land division and reclamation. The result was a combination of the practical and the pleasurable and symbolized the improvement of nature by man: the garden was a polder and became part of the rhetoric surrounding of the Garden of Holland.

In the Dutch situation the sixteenth and seventeenth were decisive in the cultural formation. Impoldering became a form of cultural production where politics, economics, and cartography came together. The regularized layout of the polder landscape paralleled contemporary ideas about civilization, ownership and statecraft. Though the term "polder" originates from the Netherlands (17th century: "polre"), that does not mean that polder landscapes as such are invented by the Dutch. From the dawn of human kind people are already taking advantage of land-water conditions to create productive landscapes while constructing water infrastructures for flood protection (dikes and dams) and water management (drainage or irrigation) in Mesopotamia from the third millennium BC onwards.15However, in the sixteenth and seventeenth century the Dutch cultivated the idea of polder-making. The polderbecame the nation’s symbol for taming nature in the struggle with the elements of water and land with a strong will and technological expertise. At the same time became land reclamation also a Dutch export product exemplified by their involvement in poldermaking across Europe and the rest of the world from the 12th century onwards until now.16

The Dutch polder landscape of today is gradually transformed into multifunctional spaces where uses such as leisure and tourism, nature, water storage and housing become more and more important besides agriculture. These developments put pressure on the quality of the space and the identity of the rural landscape. The key to solving many spatial issues lies in the wealth of shapes of the polder landscape itself.

3 UNDERSTANDING THEPOLDER LANDSCAPE

Morphological research is employed to study the Dutch polder landscape. Through exploring the morphology of the polder landscape the genius loci of the Dutch lowlands can be 'read'in order to retrieve the information and design knowledge that lies hidden within it, as clues for further development. Morphology or formal studies have proven to be useful in such a way that the landscape can be read and analysed via the medium of its physical form. The focus is on the tangible results of physical, biological and sociocultural forces. Formal analysis is an interpretative research method (also called: hermeneutics), in which knowledge is acquired through formal analysis and interpretation of visual representations of landscapes. The form is regarded a purely evidential system without prepossession regarding the meaning of its evidence, and presupposes a minimum of assumption.17This type of research is not only directed towards gaining knowledge on the architecture of the landscape, but is also focussed on cultivating spatial intelligence, the capacity to understand and design spatial compositions and relationships across scales. Morphology studies have three characteristics.18Firstly, they consider all scales of landscape, from gardens to regional landscapes. Secondly, they combine volumetric characteristics of landscape structures with patterns of space and movement. Thirdly, they are a morphogenetic approach, since the landscape architectonic composition is a product of time-the time of its conception, development or mutation. Morphology studies can also be found in urban design, architecture, art and geography.19

In landscape morphological research maps are considered to be fundamental tools for knowledge discovery. Maps have served as vehicles to represent and understand the landscape for centuries. Maps facilitate a spatial understanding of things, concepts, conditions, processes or events in the human/natural world.20They are informative as well as persuasive and are therefore important means of knowledge acquisition. This can be distinguished from knowledge acquisition through processing of spatial information that is termed mapping. Mapping refers to a process rather than a completed product. Mapping entails cartographic exploration, an activity that exploits the agency of maps and map-making to construct and communicate spatial knowledge in a visual way. In this respect mappings are not one-to-one copies of the existing situation, but their production require interpretation and reformulation. Mapping allows to 'digest' information in a rational and systematic way, which is a personal process influenced by the choices and judgments made by the interpreter, referred to as visual thinking. At the same time, these findings are made transferable via visual representation, which showcases relationships, structures and patterns, referred to as visual communication. Map dissection, map comparison, and map addition analysis are useful analytical operations.21These cartographic explorations help researchers in landscape architecture to acquire new or latent information, which is the basis for generating spatial knowledge that informs the design process. It facilitates interpretation of data to become knowledge, which serves as a base for invention through design (Fig. 4).

The morphology of the polder landscape is analysed in two stages, revealing its cohesion and variety through systematic analysis and cartography. First, all polders are surveyed and digitized resulting in the first comprehensive polder map of the Netherlands. Second, the polder as the elementary landscape unit of the lowlands is further explored.

4 COMPREHENSIVE POLDER MAP OF THE NETHERLANDS

The polder map of the Netherlands systematically visualizes the wealth in shapes of the polder landscape (Fig. 5). It is unique in a sense that it embraces the whole of the Dutch polder landscape focusing on the polder as a hydraulic and landscape entity. Though the Netherlands has a long tradition of polder cartography, with unique polder maps from individual polders or polder districts maintained by waterboards, national polder maps are lacking (Fig. 6). The polder landscape ofthe Netherlands is often described in books and mainly from the water management or historical point of view. When A.A. Beekman's Netherlands as polder land (in Dutch) appeared in 1884, he laid the first scientific foundations for the description of the Dutch polder land. Others followed in his footsteps, focusing on specific regions or lakebed polders in particular. The comprehensive polder map of the Netherlands is the first attempt on the national scale that considers the polder as a hydraulic construction and as a structure in the landscape. Insight into this connection is essential for an understanding of the polder as a spatial form with its own signature. Therefore the polder map, as a nation-wide map in which this connection is made readable, is a new step in Dutch polder cartography.22

Since the Dutch landscape changed dramatically since the beginning of the twentieth century, due to explosive urbanization and economic development, it is hardly possible to use contemporary topographic maps to identify polder units, particularly the older ones. To find a solution for this the practically intact state of the landscape, combined with the availability of detailed map material, were the most important considerations. Historical maps from the period between 1800 and 1900 offered the best opportunities for assembling a complete polder map. In this period the cities -with several exceptions-were still within their old fortifications. The landscape, as it had come to exist in the preceding centuries, could still be read in a largely unaltered state. In the 1800s surveying had already attained great precision, so that map images from the time could be projected onto contemporary maps without many problems. This was also the period when a start was made with the production of a country covering Topographic and Military Map 1850-1864 (TMK) and the Hydraulic Map first edition 1865-1891, both with a scale of 1:50.000 (Fig. 7 and 8). These two analogue historical maps served as the basis for the construction of the polder map. Further the highly accurate modern Height map of the Netherlands (AHN5), an airborne LiDAR point cloud (8 points per m2), was employed to ensure precise delineation and to identify recent polders (polders constructed after 1850) (Fig. 9).

The first step in the construction of the polder map consisted of digitalization and georeferencing of the in total 366 map sheets of the Topographic and Military Map 1850-1864 and Hydraulic Map first edition 1865-1891. The maps were scanned and transformed into a digital file consisting of pixels. The digital maps sheets were geo-rectified and georeferenced by means of a Geographic Information System (GIS). In this way the historic maps were corrected in planimetric terms and augmented with geographic coordinates related to the Dutch standard coordinate system.23This enables precise combination and exchange of geo-referenced information.

The next step was to interpret the maps, to identify the polders as spatio-hydraulic landscape units and to vectorise them (Fig. 10). The Height map of the Netherlands was used to evaluate and correct the drawing and also to identify land reclamations after 1850. The result is a GIS-based polder map of the Netherlands with 9.087 identified polder units represented on a scale of about 1:10.000 to 1:25.000, and includes all types of polders: impoldered low-lying lands, lands reclaimed from the sea, and drained lakes. More specific, the map shows all hydraulic units together with their specific boundaries. Within this framework, the polders are designated as spatial units.

The use of GIS not only ensured precision work, but also makes it possible to link information to the map, turning it into a spatial database that includes: names, year of impoldering, numerical data, etc. Based on the Geographical Dictionary of the Netherlands (Van der Aa, 1839-1851, in Dutch), a database was created with all the polders that are mentioned in this dictionary (Fig. 11). This information made it possible to supplement and check the data from the TMK and Hydraulic Map. By applying GIS the information can become spatial and available for analysis and visualization. It enabled for instance to study the development of the polder landscape in time (Fig. 12), but also computational analysis of polder properties such as: polder size, form complexity and polder form.

In order to get a grip on the wealth of polder forms the polder map was interpreted based on physical-geographical characteristics derived on differences in the substrata (rock and relief), soil and hydrology. Anthropogenic influences also play a role in this, so that, as a result of this interplay between the abiotic and anthropogenic, particular combinations of characteristics can be typical. The result is a polder typology based on physical-geographical landscapes, each of which has a number of salient formal characteristics (Fig. 13). Polder types include: sea clay polders (e.g. Tzummerpolder), peat polders (e.g. Ronde Hoep), river polders (e.g. Alblasserwaard) and IJsselmeerpolders (e.g. Noordoostpolder). Lakebedpolders (e.g. Beemster) are regarded a subtype of peat polders since they originate from peat lakes.

5 IDENTIFICATION OF POLDER GRAMMAR

Each polder can be regarded as a unique landscape unit with its own characteristics, one tesserae which goes to make up the mosaic of the whole Dutch polder landscape. Insight into the peculiar form of the polder unit provides insight into the complexity of the pattern, the morphology, the visual qualities-and with that, the identity of the Dutch lowlands. In a morphological analysis seventeen selected representative polder units are further analyzed in order to identify their polder grammar or spatial syntaxes. The polder grammar is the set of structural rules and principles that determine the spatial composition. Knowledge of the polder grammar is the starting points for new transformations of the landscape involved, or adding a new design layer. The selected polders represent the wide variety of polder types across the different physical-geographic regions in the Dutch lowlands, as well as the different time periods of impoldering (Fig. 14).

5 .1 Analytical framework

Each polder unit is introduced through description of the physical setting and the historical backgrounds followed by a detailed analysis and description of its polder grammar. In order to identify the polder grammar the constructive characteristics and the expressive characteristics of the polder form are analysed (Fig. 15). The characteristics of construction refer to the formal aspects of the transformation of the natural landscape into a habitable and exploitable agricultural landscape. The characteristics of expression refer to the implicit and explicit visual and formal elements that bring compositional, aesthetic and cultural motifs of polder making into play. In this way the polder unit is understood as a layered entity defined by the underlying natural landscape, and to a further degree by the hydraulic interventions, and finally by the organization imposed in the agricultural development of the land. Each stage leaves its traces on the form. The identification and delineation of this complex layeredness is important because this creates a point of contact for dealing with technical and landscape planning questions which may be present, such as water management or urbanization, and thus provides clues for further development of the polder landscape.

To unravel the formal systems related to the construction the following aspects are systematically analyzed and visualized for each selected polder:24

(1)Natural formal characteristics: physicalgeographic location; soil pattern, relief, natural drainage pattern and natural boundaries or contours;

(2)Hydraulic formal characteristics: form of the dikes, the pattern of drainage ditches, drainage canals and larger watercourses, the boezem system, the pumping system and water management units;

(3)Agricultural formal characteristics: the distribution of plots and their preparation for exploitation, the form of parcellation and the pattern of the roads;

(4)Formal characteristics of settlement: the farmhouse-farmstead-parcel relationship and the form and distribution of the settlements.

Regarding the characteristics related to the expression the following aspects are analyzed:

(1)Organizational model, plan type or concept;

(2)Landscape architectonic form: the basic, spatial, symbolic and programmatic form.

Historical maps, newly drawn maps and photographs are employed as important means to discover and delineate their landscape architectonic characteristics. Each polder unit is introduced through description of the physical setting and the historical backgrounds followed by detailed maps that delineate the natural landscape, terrain height, water system, basic form and spatial form of the polder under investigation.

5.2The Beemster polder as an example

In order to illustrate the application of this framework the Beemster polder is used as an example (Fig. 16).25The Beemster Lake, seventytwo square kilometres in extent, was the biggest of a series of lakes north of Amsterdam drained in the seventeenth century for land-based development.26The resulting Beemster lakebed polder was constructed between 1608 AD and 1612 AD on behalf of wealthy merchants from Amsterdam. It has since been hailed for many different reasons: as a triumph over water, a statement of Dutch power over nature, a product of technical ingenuity and organizational prowess, a site of agricultural abundance and a repository of architectural and horticultural beauty.27In this lakebed polder the relation between man and the landscape was fulfilled in the dimensions and proportions of a rational, architectonic system. The organization wasnot only functional and sustainable, but at the same time aesthetically appealing. Since 1999 the polder is designated as Unesco world heritage.

Regarding the characteristics of the natural form the contour of the Beemster is directly derived from the form of a natural peat lake, which was developed by erosion of a bog river that drained the former peat landscape (Fig. 17). The ground level varies from 1.9 to mostly 4 metres below ASL (Fig. 18). Important characteristics of the hydrologic form are determined by the windmills, ring canal, and surrounding dike. Originally 43 windmills pumped the water up in three steps into the ring canal (Fig. 19). Nowadays this is done by only a few electrical pumps. The polder was subdivided into four water management units that differed from one another in level, coordinated with the natural relief of the lake bottom. The ring canal (part of the boezemsystem) and the surrounding dike have a length of about forty-two kilometres. Agricultural formal characteristics are determined by a modular system of parcellation and it was the land surveyor Lucas Jansz Sinck (unknown-1622) who designed its layout (Fig. 20). After several changes the final grid consisted of five to six roads and four by five ditches intersected at distances of about 1.880 metres. The smallest unit in the parcellation is the 'standard parcel' of about 185 x 940 metres (Fig. 21). The head of the parcel is always connected to an access road, and the foot with a drainage ditch. Five standard parcels together form a square of about 940 x 940 metres, with drainage ditches on two sides and roads on the other two. Four of these squares form the 'Beemster square', enclosed by roads with trees and intersected by a cross of canals. The regularity of the road pattern did have a certain utility in that time, by spreading traffic over as many roads as possible, the roads remained passable. The owners were granted 'planting rights', whereby at their own expense they planted trees along the inside shoulder of the dike and along the roads in front of their parcels, nowadays determining this typical enclosed landscape spaces (Fig. 22 and 23). Regarding the settlement form the North Holland stolp, with a farmyard surrounded by a belt of trees, is the typical reclamation farmhouse of the Beemster. Some of the stolpen in the Beemster were 'gentlemen's farms'. An example, the Eenhoorn (1682) still exists (Fig. 24). The farmhouse is renowned for its representative, symmetrical front façade with its tall, expressive central section, crowned with a neck-gable, a design by the architect Philips Vingboons (1607-1678). Also there were about fifty country estates, of which most are demolished. There were regulations about the alignment of the building lots but the grid system allowed for some flexibility and variety resulting in a hierarchy of grids.28

The avenues, rooms, villages, projected squares, country estates, farmhouses, watercourses, and windmills of the Beemster together formed a new type of architectonic landscape in which the image of the Dutch landscape and the Dutch city were linked to one another in a rational arrangement. The polder came to epitomise Dutch ideas of pristine nature, wholesome and blissful living, just as it symbolised the peace and wealth of the new Dutch Republic. It was celebrated for its pastoral richness, its pleasant country estates and beautifully designed gardens.29The modular square is harmoniously embedded in the polder, and by its repetition creates the illusion of an infinite area. The experience of the natural form in itself, represented by the edge, plays no significant role. The edge is only the horizon for the system of avenues. This three-dimensionality, the illusion of an infinite plane, divided with perfect regularity that suggests the Dutch lowlands, is the most important but also the most vulnerable quality of this polder.

As exemplified by the Beemster polder the analytical framework can be used to study the constructive and expressive characteristics of the polder form, its polder grammar. In each polder the application and elaboration of the formal grammar laid out above has led to a specific form and a unique character and landscape identity in which the genius loci of the polder is captured. On the basis of these formal characteristics the various polder units can be compared with one another both spatially and temporally. Spatial similarities can be identified on the basis of geographic location and the way in which the polders were created, and temporal similarities on the basis of the period in which they were created. Various typological series can be derived from this comparison of the polders. Typological series based on the natural, hydraulic, settlement and agricultural form and also typological series based on landscape architectonic features. These series reveal the common characteristics and lines of development along which the polder landscape evolved, in terms of both the technology involved and the design.

The polder grammar is not only a vehicle for understanding the landscape architecture of the polder landscape, it can also act as the basis for future development. Through design experiments based on the polder grammar one can investigatewhich and how elements from the polder landscapes can be transformed, and in what form to adapt to economic and climate change. Landscape architecture design experiments - research by design - can help to explore the possibilities for spatial development, generating proposals or potential solutions for design problems.30This type of knowledge based design leads to new, balanced and coherent polder landscapes with their own identity and spatial qualities.

6 IN CONCLUSION

Polder landscapes change. Sometimes there are profound changes taking place, sometimes less radical changes. Therefore the polder landscape should be understood as a dynamic system that continually transforms under the influence of natural processes and social requirements. The natural landscape was formed by geological processes without human intervention. The cultural landscape emerged from the reclamation, colonization and technical mastery of the natural landscape. As such is the polder a result of the interaction between the conditions offered by the natural landscape, the technical possibilities for reclamation and water management, and the sociocultural context. As such is the polder landscape a layered entity where traces that time has laid over can reinforce or contradict each other with a wide variety of polderscapes as a result, each with their own identity. However, the polder landscape remains subject to change. Due to rapid urban development, function change, etc. these rural landscapes often suffer from levelling tendencies and standardization that negate the characteristic spatial differences with the loss of cultural identity as a result. Therefore it is necessary to understand these landscapes from a landscape architecture point of view in order to retrieve the information and design knowledge that lies hidden within it and then apply them in the right way.

This article presented a particular way of understanding the coherence and variation of the polder landscape providing clues for spatial planning and design through systematic delineation and the identification of spatial design principles. As exemplified by the Dutch case this resulted in the first comprehensive polder map of the Netherlands. The map provides both an overview and a ‘benchmark’, a point of reference from which the history of the polder landscape can be reconstructed and that provides a perspective of the present and the future. Also the polder as the elementary landscape unit of the lowlands is further explored. In a morphological analysis of selected examples the characteristics of the different polder types (sea clay polders, river polders, lake bed polders and peat polders) are enumerated and interpreted typologically. Though the Dutch polder landscape played a central role here, the principles of study are applicable in a global context. The presented methodology embodies a way of thinking typical for landscape architecture and has three characteristics: First, it entails a multi-scalar approach covering the polder land in total but also addresses individual polders through the identification of polder grammar. Second, it combines spatio-visual structures with patterns of water management. Third, it explores the landscape via the medium of its tangible form as a result of physical, biological and socio-cultural forces. An analysis of this sort makes the polder landscape, which until now often is discussed only in water management and historical terms, accessible for spatial design disciplines while providing clues for preservation and transformation.

1 Examples from the water management and historical perspective include: Rippon, S. (2000) The transformation of coastal wetlands. Exploitation and management of marshland landscapes in North West Europe during the Roman and Medieval periods. New York: Oxford University Press; Van der Ven, (2004) Man-made lowlands. History of water management and land reclamation in the Netherlands. Utrecht: International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage. An example from the cultural perspective: Wagret, P. (1968) Polderlands. London; Methuen & Co.

2 Reh, W., Steenbergen, C.M. & Aten, D. (2007) Sea of Land. The polder as an experimental atlas of Dutch landscape architecture. Wormer: Uitgeverij Noord-Holland; Steenbergen, C. M., Reh, W., Nijhuis, S., & Pouderoijen, M. T. (2009) The Polder Atlas of the Netherlands. Pantheon of theLowlands. Bussum: THOTH publishers; Nijhuis, S & Pouderoijen, MT (2013) De polderkaart van Nederland. Een instrument voor de ontwikkeling van het laagland (The poldermap of the Netherlands. An instrument for spatial development of the lowlands). Bulletin KNOB 3; 137-151. DOI: 10.7480/knob.112.2013.3.626

3 Centre for Civil Engineering Research and Codes (CUR) (1993) Hydrology and water management of deltaic areas. Rotterdam: Balkema, p. 230.

4 Cf. CUR 1993 (note 3), p. 230.

5 Sauer, C.O. (1963) ‘The morphology of landscape’. In J. Leighly (Eds.) Land and life. A selection from the writings of Carl Ortwin Sauer(pp. 315-350). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. (Original article published 1925), p. 327.

6 See for an overview of the oldest known water infrastructures in the Netherlands: Lascaris, M. & De Kraker,

A. (2013) ‘Dikes and other hydraulic engineering works from the Late Iron Age and Roman Period on the coastal area between Dunkirk and the Danish Bight’. In: Thoen, E. et al. (eds.) Landscapes or seascapes? The history of the coastal environment in the North Sea Area reconsidered (pp. 177-198). Turnhout, Brepols.

7 See for a history of Dutch surveying and cartography: Koeman, C. & Van Egmond, M. (2007) ‘Surveying and official mapping in the Low Countries, 1500-ca. 1670’. In: Woodward, D. (Ed.) The history of cartography. Volume III: Cartography in the European Renaissance (pp. 1246-1295). Chicago: Chicago University Press.

8 Sutton, E. (2015) Capitalism and cartography in the Dutch golden age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

9 Van der Heuvel, C. (2011) ‘Multilayered grids and Dutch town planning. Flexibility and temporality in the design of settlements in the low countries and overseas’, In: Lombaerde, P. & Van de Heuvel, C. (eds.) Early modern urbanism and the grid (pp. 27-44). Turnhout: Brepols, p. 44.

10 Van der Heuvel 2011 (note 9), p. 44.

11 Bezemer-Sellers, V. (2001) Courtly gardens in Holland, 1600-1650. Amsterdam: Architectura& Natura Press. p. 9.

12 De Jong, E. (2000) Nature and art. Dutch garden and landscape architecture, 1650-1740. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, p. 18.

13 De Jong 2000 (note 12), p. 21.

14 Bezemer-Sellers 2001 (note 11), p. 21.

15 Viollet, P.L. (2007)Water engineering in ancient civilizations: 5,000 years of history. Madrid: International Association of Hydraulic Engineering and Research.

16 See for the role the Dutch played in polder-making around the globe in a historical and modern perspective: Veen, J. v. (1952). Dredge, Drain, Reclaim. The art of a nation. The Hague; Segeren, W.A. et al. (1983) Polders of the world. Final report. Wageningen; Danner, H. et al. (2005) Polder Pioneers. The influence of Dutch Engineers on water management in Europe. Utrecht.

17 Sauer 1963 (note 5), p. 327.

18 Adapted from Moudon, A. V. (1994)‘Getting to know the built landscape: Typomorphology’. In K. A. Frank, & L. H. Schneekloth (Eds.), Ordering space. Types in architecture and design (pp. 289-309). New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

19 For an overview of morphological approaches see: Nijhuis, S. (2015) GIS-based landscape design research. Stourhead landscape garden as a case study. Delft: A+BE, p. 48ff.

20 Harley, J. B., & Woodward, D. (Eds.) (1987) The history of cartography. Vol. I: Cartography in prehistoric, ancient and medieval europe and the mediterranean. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, p. xiv.

21 Nijhuis, S. & Pouderoijen, M.T. (2014) ‘Mapping urbanized deltas’, in: Meyer, H & Nijhuis, S (eds.) Urbanized deltas in transition (pp. 10-22). Amsterdam: Techne Press.

22 See for a full elaboration: Nijhuis & Pouderoijen 2013 (note 2) and Steenbergen et al. 2009 (note 2), pp. 74 ff.

23 See for more backgrounds on the use of historical maps, digitalization, georeferencing, etc.: Nijhuis 2015 (note 19), p. 109 ff.

24 See for backgrounds: Steenbergen et al. 2009 (note 2), pp. 28-29.

25 For a more elaborate description of the constructive and expressive characteristics of the Beemster polder and other polders see: Steenbergen et al. 2009 (note 2), pp. 338-353, pp. 198-469.

26 Van der Ven 2004 (note 1).

27 Fleischer, A. (2007) ‘The Beemster Polder: Conservative Invention and Holland'sGreatest Pleasure Garden’. In: Roberts, L. et al. (eds.) The mindful hand. Inquiry and invention from the Late Renaissance to Early Industrialization (pp. 145-166). Assen: Royal van Gorcum.

28 Van der Heuvel 2011 (note 9), p. 44.

29 Fleischer 2007 (note 26).

30 Nijhuis, S, & Bobbink, I (2012) ‘Design-related research in landscape architecture’, J. Design Research 10 (4), 239-257. DOI: 10.1504/JDR.2012.051172.

Polderscapes: The Landscape Architecture of the Dutch Lowlands

The Dutch lowlands consist mainly of polders, areas where water levels are artificially controlled so people can live and work there. This centuries-old interaction between man and water has produced a rich polder landscape. The great variety in polder forms is caused by differences in the geological subsoil, the dynamics of water and land and human intervention. This research systematically explores and visualizes the wealth in shapes of the Dutch polder landscape from a landscape architecture perspective. Polders are not just regarded as hydraulic phenomena but also as spatial constructions and cultural expressions: the polder landscape as one can see and experience it, and also as an expression of Dutch culture. Through exploring the morphology of the polder landscape the genius loci of the Dutch lowlands can be ‘read’ in order to retrieve the information and design knowledge that lies hidden within it, as clues for further development. In this research the landscape architectonic form of the polder landscape is analyzed in two stages revealing its cohesion and variety through systematic analysis and cartography. First, all polders are surveyed and digitized resulting in the first systematic polder map of the Netherlands. The use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) not only ensured precision work, but also made it possible to link information to the map, turning it into a spatial database. Second, the polder as the elementary landscape unit of the lowlands is further explored. In a morphological analysis of selected examples the characteristics of the different polder types (sea clay polders, river polders, lake bed polders and peat polders) are enumerated and interpreted typologically. An analysis of this sort makes the polder landscape, which until now has been discussed only in physical and historical-geographical terms, accessible for spatial design disciplines while providing clues for preservation and transformation.

Polder Landscapes; Design Analysis; Dutch Lowlands; Formal Analysis; Typology; Mapping

TU986

A

1673-1530(2016)08-0038-20

10.14085/j.fjyl.2016.08.0038.20

2016-04-23

2016-07-25

斯蒂芬·奈豪斯/男/助理教授/博士 /风景园林研究项目负责人/荷兰代尔伏特理工大学(TUD)建筑与建成环境学院/研究方向:风景园林研究、圩田设计、三角洲景观、基于景观的区域设计和GIS在风景园林规划设计领域的应用

Author:

Dr. Steffen Nijhuis is Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture and Team Leader Landscape Architecture Research Programme at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology (theNetherlands). He is an expert in landscape architecture research and design of polder and delta landscapes, landscape-based regional design approaches to urban development, and GIS-applications in landscape planning and design.