胰腺导管腺癌肝转移患者姑息性治疗后的预后因素分析

2016-12-22欧阳华强马维东刘方方明慧权曼曼潘战宇

欧阳华强 马维东 刘方 方明慧 权曼曼 潘战宇

·论著·

胰腺导管腺癌肝转移患者姑息性治疗后的预后因素分析

欧阳华强 马维东 刘方 方明慧 权曼曼 潘战宇

目的 分析伴肝转移的胰腺导管腺癌(PALM)患者接受姑息性治疗后影响预后的因素。方法 回顾性分析天津医科大学肿瘤医院2001年1月至2015年12月间经病理确诊并仅接受姑息性治疗的108例PALM患者的临床特征、治疗方法及生存状况。采用Kaplan-Meier法计算生存率,采用单因素及多因素Cox比例风险回归模型分析影响患者生存时间的因素。结果 108例患者中男性68例,女性40例,平均年龄58岁。患者本人或家属拒绝接受抗肿瘤治疗者77例(71.3%)。所采用的姑息治疗方法包括5例次(4.6%)在剖腹探查后行胆总管空肠吻合和(或)胃空肠吻合术,21例次(19.4%)行经皮肝穿刺胆道外引流术,79例次(73.1%)行药物镇痛治疗,17例次(15.7%)行药物联合腹腔神经阻滞术镇痛治疗。全组患者的中位生存期为94d。患者功能状态(KPS)评分<80分、淋巴结转移、腹水、空腹血糖≥6.1mmol/L、LDH≥250U/L为影响PALM患者预后的独立危险因素。按患者同时有上述0~1、2~3、4~5个因素分为危险度低、中、高组,3组患者的中位生存时间分别为137、95、48d,差异有统计学意义(P<0.0001)。结论KPS评分、淋巴结转移、腹水、空腹血糖和LDH水平是PALM患者预后的危险因素,据此进行危险度分组更有利于个体化的肿瘤预后判断,并可为临床决策提供参考。

胰腺肿瘤; 肝肿瘤,继发性; 姑息疗法; 预后

Fund programs: National Natural Science Foundation of China (81503562); National Key Clinical Specialist Construction Programs of China (2013-544)

胰腺癌是恶性程度极高的消化系统肿瘤,2014年全球胰腺癌新发337 872例,死亡330 391例[1-3]。绝大多数患者在就诊时已属晚期,失去根治性手术机会。胰腺癌85%以上为导管腺癌[4],其5年生存率仅为5%~8%,且在最近10年内未见明显改观[5-6]。肝脏是胰腺癌远处转移最常发生的脏器,胰腺导管腺癌合并肝转移(pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with synchronous liver metastases, PALM)患者因体质状况欠佳或脏器功能不全,无法接受放、化疗等抗肿瘤治疗,预后更差[7]。本研究回顾性分析仅接受姑息治疗的PALM患者的临床资料与随访结果,以探讨PALM的临床特征、生存情况及影响预后的相关因素。

资料与方法

一、研究对象

2001年1月至2015年12月天津医科大学肿瘤医院共收治胰腺癌患者3 592例,其中经组织病理学或细胞学检查证实为胰腺外分泌癌1 530例,排除724例未发生肝转移、122例非导管腺癌、177例在胰腺癌确诊后超过3个月发现肝转移、399例接受过根治性手术及系统化疗、放疗、靶向治疗、介入治疗和其他物理治疗等患者,共108例单纯行姑息性治疗患者纳入本研究。

二、研究方法

收集患者初次就诊时的基本临床资料及治疗方法,并采用信件、电话、门诊复查等方式进行随访,截止日期为2016年4月30日。6例失访,随访率为94.4%,中位随访35.2个月。

三、统计学处理

采用Stata 12.0软件进行统计学分析。生存时间为从影像学检查确诊胰腺导管腺癌伴肝转移到患者死亡或随访截止日。失访病例截止到末次随访日,作为截尾数据纳入统计学分析。采用Kaplan-Meier法计算生存率,Log-rank法进行组间比较。影响患者生存时间的因素先采用单因素分析法,取P<0.05的因素及其他临床公认的因素建立Cox比例风险回归模型进行多因素分析。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结 果

一、临床资料

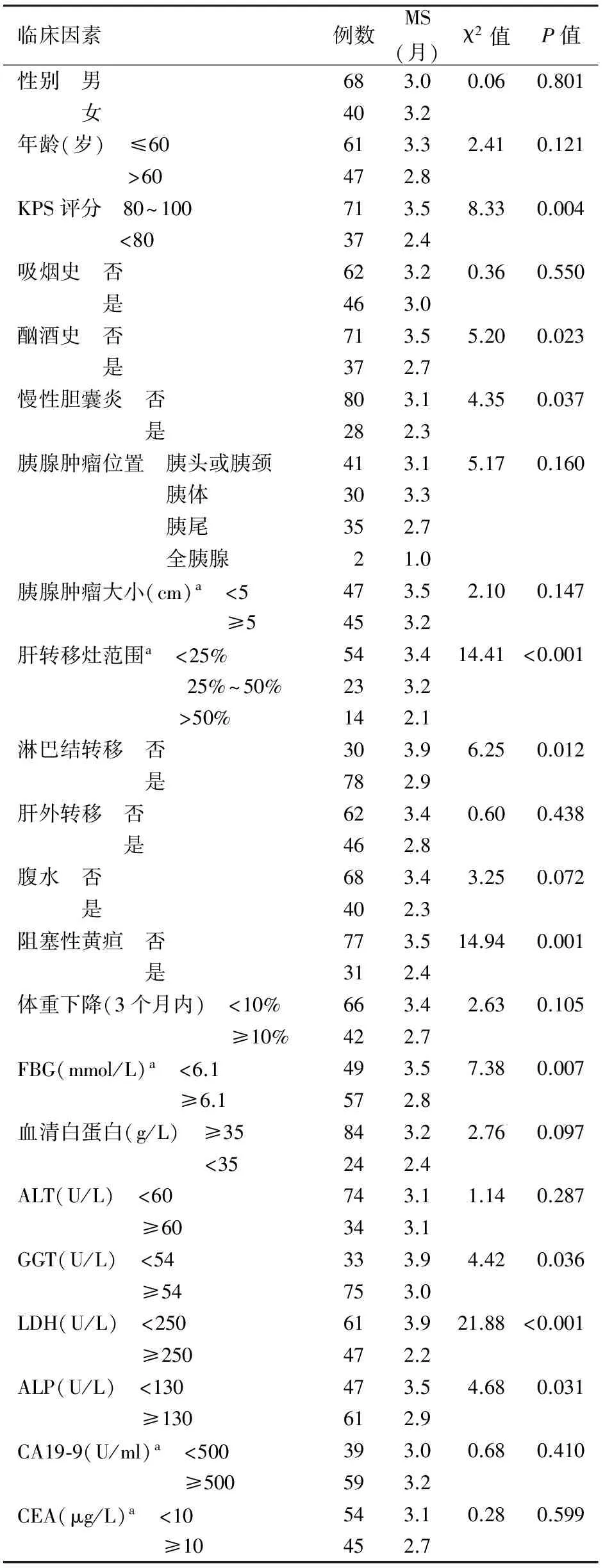

108例患者中男性68例,女性40例,年龄31~78岁,平均58岁;患者功能状态(KPS)评分40~100分,平均77分;胰腺肿瘤最大径2~14 cm,平均5.4 cm;肝转移灶最大径0.4~14.5 cm,平均3.4 cm(表1)。

在PALM诊断明确后,77例(71.3%)患者本人或家属直接放弃抗肿瘤治疗,15例(13.9%)在化疗1次后因不良反应较大拒绝继续化疗,9例(8.3%)患者因体能状况极差(KPS≤60分)不能耐受化疗,7例(6.5%)因肝、肾、心功能不全或合并其他特殊疾病不能接受化疗(表1)。

二、姑息性治疗方法

5例次(4.6%)在剖腹探查后行胆总管空肠吻合和(或)胃空肠吻合术,21例次(19.4%)行经皮肝穿刺胆道外引流术,17例次(15.7%)行药物联合腹腔神经阻滞术镇痛治疗,79例次(73.1%)行药物镇痛治疗。同时,所有患者住院期间均给予对症营养支持治疗。

三、生存率

除6例失访外,其余患者均随访至生命终止。108例患者的生存时间为13~293 d,中位生存期(MS)为94 d,半年生存率为12.2%。

四、预后因素分析

单因素分析结果显示,KPS评分、酗酒史、慢性胆囊炎、肝转移灶范围、淋巴结转移、阻塞性黄疸、空腹血糖(FBG)及血清GGT、LDH、ALP水平是影响患者预后的危险因素(表1)。将这10个变量以及既往文献[8-10]与临床上较为公认的胰腺肿瘤大小、腹水、血清白蛋白、CA19-9水平纳入Cox比例风险模型进行多因素分析,结果显示KPS评分<80分、淋巴结转移、有腹水、FBG≥6.1 mmol/L及LDH≥250 U/L为影响患者预后的独立危险因素(表2)。按患者同时有上述0~1、2~3、4~5个因素分为危险度低、中、高3个组,3组患者的MS分别为137、95、48 d,半年生存率分别为27.7%、9.5%、7.0%,差异有统计学意义(χ2=38.38,P<0.0001,图1)。

表1 108例PALM患者的一般资料及单因素分析

注:a部分患者资料缺如

表2 108例PALM患者预后的多因素分析

图1 108例PALM患者危险度分组的生存曲线

讨 论

PALM患者因病灶广泛,进展迅速,基本失去根治性手术机会。尽管小样本回顾性资料提示对于经过高度选择的PALM患者实行肝、胰腺肿瘤同步切除术可能有一定价值[11-13],但该类手术适应证欠明确,部分报道对此持否定态度[14-15]。化疗时采用吉西他滨联合白蛋白结合型紫杉醇、FOLFIRINOX方案等可在一定程度上延长转移性胰腺癌患者的生存期,疗效优于吉西他滨单药[16-17]。针对肝转移灶的局部治疗可采用肝动脉灌注(栓塞)化疗、经皮肝穿刺射频消融治疗、高强度聚焦超声、氩氦冷冻及放射性粒子植入术等[18-22]。但以上治疗方法多以小样本或个案报道为主,仅作为综合治疗手段的补充,需要依据多学科团队集体会诊的意见酌情考虑。

本研究探讨姑息性治疗模式下PALM患者的生存情况与影响患者预后的相关因素。结果显示,多数患者在确诊时即已进入疾病终末期,无积极治疗的机会,患者及其家属更倾向于实行无创性的姑息治疗方案,仅少数患者接受姑息性内引流术、经皮肝穿刺胆道引流术及腹腔神经阻滞术。文献报道,各种姑息性减黄术均以缓解胰腺癌患者的症状和改善生活质量为目的,内镜下旁路手术适用于生存预期在6个月以内者,而对于生存预期更长者,推荐选择开放性旁路手术[23]。

本研究重点探讨影响姑息性治疗的PALM患者的预后因素。结果显示,KPS<80分、淋巴结转移、有腹水、LDH≥250 U/L、FBG≥6.1 mmol/L是影响PALM患者的独立危险因素。前4个因素在既往文献中报道甚多[9,24-26],而高血糖则较少提及。胰腺癌常并发糖尿病,某些患者往往在明确诊断前后偶然发现血糖升高。本组中有22例为慢性糖尿病患者,但首次就诊时FBG≥6.1 mmol/L者达57例(52.8%),不排除部分为新发糖尿病。PALM合并糖尿病患者的中位生存时间与无糖尿病者无显著差异(3.5个月比3.0个月,χ2=0.001,P=0.99),但若以空腹血糖≥6.1 mmol/L进行比较,则对应两组的差异具有统计学意义(P<0.01),提示高血糖为PALM独立的预后危险因素。因本组患者生存期短,绝大多数患者并未参照糖尿病诊断流程进一步完善检查,是否如Li等[27]报道的新发糖尿病为转移性胰腺癌患者死亡风险的独立预测因子,尚待进一步考证。

本研究参照Cox比例风险模型得出的5个危险因素,对108例PALM患者进行了危险度分组,结果提示各组间生存率差异具有统计学意义(P<0.0001)。危险度分组为评估患者整体预后提供了便捷有效的方法,并可为临床决策奠定基础。高危组患者中位生存时间仅48 d,应以姑息治疗为主要措施;而对于中、低危组的患者,则有可能通过积极的多学科治疗方案改善预后,延长生存期。

诚然,本研究存在一定的局限性。首先,作为回顾性分析难免存在病例选择上的偏倚。其次,由于样本量所限,对于少数患者合并的脏器功能不全及其他伴随疾病,并未纳入预后因素分析。此外,由于时间跨度较长,患者接受姑息治疗前后的某些数据记录不全,难以充分评估姑息治疗的疗效及其对生存期的影响。故本研究的重点为非治疗因素的预测价值,以便为将来的PALM患者可能接受抗肿瘤治疗提供参考。

[1] 杨尹默.胰腺癌外科治疗的热点与难点[J].中华消化外科杂志,2015,14(8):612-614.DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-9752.2015.08.004.

[2] 中华医学会外科学分会胰腺外科学组.胰腺癌诊治指南(2014版)[J].中华消化外科杂志,2014,13(11):831-837.DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-9752.2014.11.001.

[3] Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012[J]. Int J Cancer, 2015, 136(5): E359-E386. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.29210.

[4] Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2014,371(11):1039-1049. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM ra 1404198.

[5] Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2016[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2016, 66(1):7-30. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21332.

[6] Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2015, 65(2):87-108. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21262.

[7] Kim HW, Lee JC, Paik KH, et al. Initial metastatic site as a prognostic factor in patients with stage IV pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2015, 94(25):e1012. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001012.

[8] Zhang DX, Dai YD, Yuan SX, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with pancreatic cancer[J]. Exp Ther Med, 2012, 3(3): 423-432. DOI: 10.3892/etm.2011.412.

[9] Bilici A. Prognostic factors related with survival in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20(31):10802-10812. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10802.

[10] 欧阳华强, 潘战宇, 马维东, 等. 胰腺癌肝转移497例多学科治疗临床分析 [J]. 中华医学杂志, 2016, 96(6):425-430. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491. 2016.06.003.

[11] Seelig SK, Burkert B, Chromik AM, et al. Pancreatic resections for advanced M1-pancreatic carcinoma: the value of synchronous metastasectomy[J]. HPB Surg, 2010, 2010:579672. DOI: 10.1155/2010/579672.

[12] Zanini N, Lombardi R, Masetti M, et al. Surgery for isolated liver metastases from pancreatic cancer[J]. Updates Surg, 2015, 67(1):19-25. DOI: 10.1007/s13304-015-0283-6.

[13] Tachezy M, Gebauer F, Janot M, et al. Synchronous resections of hepatic oligometastatic pancreatic cancer: Disputing a principle in a time of safe pancreatic operations in a retrospective multicenter analysis[J]. Surgery, 2016, 160(1):136-144. DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.02.019.

[14] Gleisner AL, Assumpcao L, Cameron JL, et al. Is resection of periampullary or pancreatic adenocarcinoma with synchronous hepatic metastasis justified[J]. Cancer, 2007, 110(11):2484-2492. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.23074.

[15] Takada T, Yasuda H, Amano H, et al. Simultaneous pancreatic resection with pancreato-duodenectomy for metastatic pancreatic head carcinoma: does it improve survival[J]. Hepatogas-troenterology, 1997, 44(14):567-573.

[16] Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2011, 364(19):1817-1825. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923.

[17] Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine[J]. N Engl J Med, 2013, 369(18):1691-1703. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369.

[18] Azizi A, Naguib NN, Mbalisike E, et al. Liver metastases of pancreatic cancer: role of repetitive transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) on tumor response and survival[J]. Pancreas, 2011, 40(8):1271-1275. DOI: 10.1097/MPA. 0b013e318220e5b9.

[19] Gillams AR, Lees WR. Radio-frequency ablation of colorectal liver metastases in 167 patients[J]. Eur Radiol, 2004, 14(12):2261-2267. DOI: 10.1007/s00330-004-2416-z.

[20] Dupré A, Melodelima D, Pérol D, et al. First clinical experience of intra-operative high intensity focused ultrasound in patients with colorectal liver metastases: a phase I-IIa study[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(2):e0118212. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118212.

[21] Yu YP, Yu Q, Guo JM, et al. (125) I particle implantation combined with chemoradiotherapy to treat advanced pancreatic cancer[J]. Br J Radiol, 2014, 87(1036):20130641. DOI: 10.1259/bjr.20130641.

[22] Wu S, Hou J, Ding Y, et al. Cryoablation versus radiofrequency ablation for hepatic malignancies: A systematic review and literature-based analysis[J]. Medicine(Baltimore), 2015, 94(49):e2252. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002252.

[23] Boulay BR, Parepally M. Managing malignant biliary obstruction in pancreas cancer: choosing the appropriate strategy[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20(28):9345-9353. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9345.

[24] Lo Re G, Santeufemia DA, Foltran L, et al. Prognostic factors of survival in patients treated with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine regimen for advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a single institutional experience[J]. Oncotarget, 2015, 6(10):8255-8260. DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget.3143.

[25] Tabernero J, Chiorean EG, Infante JR, et al. Prognostic factors of survival in a randomized phase III trial (MPACT) of weekly nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer[J]. Oncologist, 2015, 20(2):143-150. DOI: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0394.

[26] Tas F, Karabulut S, Ciftci R, et al. Serum levels of LDH, CEA, and CA19-9 have prognostic roles on survival in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer receiving gemcitabine-based chemotherapy[J]. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2014, 73(6):1163-1171. DOI: 10.1007/s00280-014-2450-8.

[27] Li D, Mao Y, Chang P, et al. Impacts of new-onset and long-term diabetes on clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer[J]. Am J Cancer Res, 2015, 5(10):3260-3269.

(本文编辑:吕芳萍)

Analysis of prognostic factors in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and synchronous liver metastases after palliative treatment

OuyangHuaqiang,MaWeidong,LiuFang,FangMinghui,QuanManman,PanZhanyu.

TianjinMedicalUniversityCancerHospital,NationalClinicalResearchCenterofCancer,KeyLaboratoryofCancerPreventionandTherapy,Tianjin300060,China

PanZhanyu,Email:zpan@tmu.edu.cn

Objectives To explore the prognostic factors of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and synchronous liver metastases (PALM) receiving palliative treatment. Methods The clinical characteristics, therapeutic approaches and survival outcomes of 108 consecutive patients with PALM who were pathologically diagnosed and received only palliative treatment at Tianjin Medical University Cancer Hospital from January 2001 to December 2015. were retrospectively analyzed. Survival rates were calculated by Kaplan-Meier method, and factors influencing the survival were analyzed by univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model. Results Of these patients, 68 were male and 40 were female, with an average age of 58 years old. Seventy-seven (71.3%) cases or their relatives refused to receive anticancer therapies. Palliative treatments included choledochojejunostomy and/or gastrojejunostomy after exploratory laparotomy for 5 (4.6%) cases, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (n=22, 19.4%), drug analgesia (n=79, 73.1%), drug analgesia combined with percutaneous neurolytic coeliac plexus block (n=17, 15.7%). The median survival time (MS) was 94 days in all patients. Karnofsky performance score (KPS)<80, lymph node metastases, ascites, fasting blood glucose ≥6.1 mmol/L and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) ≥250 U/L were independent risk factors influencing prognosis of PALM. Three groups were categorized according to the number of the above 5 risk factors for 0~1 in low risk group, 2~3 in middle risk group and 4~5 in high risk group, and the MS of 3 groups was 137, 95 and 48 days, respectively, with an extremely statistical significance (P<0.0001). Conclusions KPS, lymph node metastases, ascites, fasting blood glucose and LDH were the risk factors for prognosis of PALM. Patient stratification according to the above factors is more advantageous for judging individualized prognosis and can provide reference for making clinical decision.

Pancreatic neoplasms; Liver neoplasms, secondary; Palliative care; Prognosis

10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-1935.2016.06.003

300060 天津,天津医科大学肿瘤医院中西医结合科,国家肿瘤临床医学研究中心,天津市肿瘤防治重点实验室

潘战宇,Email: zpan@tmu.edu.cn

国家自然科学基金(81503562);国家临床重点专科建设项目(2013-544)

2016-06-29)