Modifiable determinants of attitude towards dengue vaccination among healthy inhabitants of Aceh, Indonesia: Findings from a communitybased survey

2016-11-24HarapanHarapanSamsulAnwarAslamBustamanArsilRadiansyahPradibaAngrainiRinyFasliSalwiyadiSalwiyadiRezaAkbarBastianAdeOktiviyariImaduddinAkmalMuhammadIqbalaminJamalulAdilFenniHenrizalDarmayantiDarmayantiRovyPratamaJhonyKaruniaF

Harapan HarapanSamsul Anwar, Aslam Bustaman, Arsil Radiansyah, Pradiba Angraini, Riny Fasli, Salwiyadi Salwiyadi, Reza Akbar Bastian, Ade Oktiviyari, Imaduddin Akmal, Muhammad Iqbalamin, Jamalul Adil, Fenni Henrizal, Darmayanti Darmayanti, Rovy Pratama, Jhony Karunia Fajar, Abdul Malik Setiawan, Mandira Lamichhane Dhimal, Ulrich Kuch, David Alexander Groneberg, R. Tedjo Sasmono, Meghnath Dhimal,9, Ruth Mueller

1Medical Research Unit, School of Medicine, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

2Tropical Disease Centre, School of Medicine, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

3Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

4Department of Statistics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

5Department of Biology, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

6Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, State Islamic University Maulana Malik Ibrahim, Malang, Indonesia

7Institute of Occupational Medicine, Social Medicine and Environmental Medicine, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

8Eijkman Institute for Molecular Biology, Jakarta, Indonesia

9Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC), Ministry of Health Complex, Kathmandu, Nepal

Modifiable determinants of attitude towards dengue vaccination among healthy inhabitants of Aceh, Indonesia: Findings from a communitybased survey

Harapan Harapan1,2,3,✉Samsul Anwar4, Aslam Bustaman5, Arsil Radiansyah1, Pradiba Angraini1, Riny Fasli1, Salwiyadi Salwiyadi1, Reza Akbar Bastian1, Ade Oktiviyari1, Imaduddin Akmal1, Muhammad Iqbalamin1, Jamalul Adil1, Fenni Henrizal1, Darmayanti Darmayanti1, Rovy Pratama1, Jhony Karunia Fajar1, Abdul Malik Setiawan6, Mandira Lamichhane Dhimal7, Ulrich Kuch7, David Alexander Groneberg7, R. Tedjo Sasmono8, Meghnath Dhimal7,9, Ruth Mueller7

1Medical Research Unit, School of Medicine, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

2Tropical Disease Centre, School of Medicine, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

3Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

4Department of Statistics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

5Department of Biology, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

6Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, State Islamic University Maulana Malik Ibrahim, Malang, Indonesia

7Institute of Occupational Medicine, Social Medicine and Environmental Medicine, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

8Eijkman Institute for Molecular Biology, Jakarta, Indonesia

9Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC), Ministry of Health Complex, Kathmandu, Nepal

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Accepted 2 August 2016

Available online 20 November 2016

Attitude towards vaccination

Dengue fever

Dengue vaccine

Dengue

Indonesia

Vaccine introduction program

Objective: To explore and understand the attitude towards dengue vaccination and its modifiable determinants among inhabitants of Aceh (northern Sumatra Island, Indonesia), the region that was most severely affected by the earthquake and tsunami of 26 December 2004. Methods: A communitybased, cross-sectional study was conducted among 535 healthy inhabitants in nine regencies (Kabupaten or Kotamadya) of Aceh that were selected randomly from November 2014 to March 2015. A set of validated, pre-tested, structured questionnaires was used to guide the interviews. The questionnaires covered a range of explanatory variables and one outcome variable (attitude to dengue vaccination). Multi-step logistic regression analysis and Spearman`s rank correlation were used to test the role of explanatory variables for the outcome variable. Results: More than 70% of the participants had a poor attitude towards dengue vaccination. Modifiable determinants associated with poor attitude to dengue vaccination were low education level, working as farmers and traditional market traders, low socioeconomic status and poor knowledge, attitude and practice regarding dengue fever (P<0.05). The KAP domain scores were correlated strongly with attitude to dengue vaccination, rs=0.25, rs=0.67 and rs=0.20, respectively (P<0.001). Multivariate analysis found that independent predictors associated with attitude towards dengue vaccination among study participants were only sex and attitude towards dengue fever (P<0.001). Conclusions: This study reveals that low KAP regarding dengue fever, low education level and low socioeconomic status are associated with a poor attitude towards dengue vaccination. Therefore, inhabitants of suburbs who are working as farmers or traditional market traders with low socioeconomic status are the most appropriate target group for a dengue vaccine introduction program.

1. Introduction

Infection by dengue viruses is a major global public healthconcern, resulting in significant morbidity, mortality, and economic cost, particularly in developing countries [1]. Approximately half of the world's population is at risk and about 70% of those at risk live in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific regions [2]. In Indonesia, one of the largest countries in this region, the incidence of dengue fever has rapidly increased in the last 45 years, from 0.05 in 1968 to 35-40 per 100 000 population in 2013 [3]. In 2014, there were 100 347 registeredcases (39.8 per 100 000) and 907 of those died [4].

One of the Indonesia's provinces with an increased incidence of dengue fever is Aceh [5]. Located at the northwestern end of Sumatra island, Aceh was the most severely affected area in the earthquake and tsunami catastrophe of 26 December 2004. A study revealed an increasing trend of dengue fever cases in Aceh, from 2.76 per 100 000 population in 2003 to 35.36 per 100 000 population in 2009 and 56.40 per 100 000 population in 2011 [6]. Another recent report suggested that the total number of dengue fever cases in Aceh in 2014 was 2 208 [7]. This upward trend of dengue fever cases suggests that prevention and control programs have not been able to reduce the number of dengue virus infections in Aceh.

Governments and policymakers in dengue fever hyper-endemic regions have started to consider the possible advantages of dengue prevention programs using vaccination [8]. Data on the efficacy and the long-term safety of a dengue virus vaccine, the Sanofi-Pasteur chimeric yellow fever-dengue virus tetravalent vaccine (CYD-TDV), have been published from Phase III trials [9]. Recently, CYD-TDV was approved in the Philippines, Mexico, and Brazil. Vaccination programs critically depend on public acceptance and may need to be adapted accordingly, to better suit regional or local contexts. Economic and public acceptance factors of vaccination may influence the adaptation of vaccination strategies in certain regions, especially in developing countries [10]. Therefore, assessing and understanding the attitude towards vaccination and its modifiable determinants among the target population is necessary for an accelerated introduction of dengue virus vaccines into the public sector program and private markets in countries like Indonesia. In this study, the attitude towards dengue vaccination among healthy inhabitants of Aceh, Indonesia were assessed and the potential modifiable determinants that influence the attitude towards vaccination were determined.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

This community-based cross-sectional survey was carried out to assess the attitude towards dengue vaccination and to determine its modifiable determinants among healthy inhabitants of Aceh, a province located at the northern end of Sumatra island, in the westernmost part of the Indonesian archipelago. To achieve these aims, a set of validated questionnaires was used to conduct the interviews with the participants. The reliability of the questionnares was tested in two regencies of Aceh province (Aceh Barat Daya and Aceh Pidie Jaya) and the actual study was conducted in nine regencies (Kabupaten or Kotamadya) (Aceh Tengah, Aceh Besar, Aceh Utara, Aceh Singkil, Aceh Timur, Aceh Selatan, Aceh Tamiang, Langsa and Sabang) from November 2014 to March 2015.

2.2. Target population and sampling procedure

To represent the target population (4 791 924), 385 participants were required as the minimum sample size. This number was based on the assumption that 50% of the participants had a good attitude towards vaccination with a 5% margin of error and 95% confidence level. To recruit the minimum number of participants, nine out of 23 regencies in Aceh were selected randomly. Higher numbers of participants were recruited for regencies with higher population numbers. The following combination of inclusion criteria was applied: healthy individual over 16 years of age; residence in the current regency during more than 3 months prior to the study and; ability to communicate in Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian).

2.3. Study instruments

A set of validated structured questionnaires from previous studies [11-14] was used to guide the interviews. The questionnaires covered demographic data, the history of previous dengue infection, socioeconomic status (SES), knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) regarding dengue, and attitude towards dengue vaccination. The questionnaires were tested for reliability prior to use in the actual study. The reliability test for the KAP domain was conducted among 50 participants while other domains were tested among 30 participants in Aceh Barat Daya and Aceh Pidie Jaya regencies. The minimal Cronbach's alpha 0.7 was considered as indicating good internal consistency. In addition, the normality of the KAP scores and attitude towards dengue vaccination was analyzed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

2.4. Outcome variable

To measure the attitude towards vaccination, five modified questions from a previous study were used [12]. Each question had five possible answers in a Likert-like scale indicating their agreement regarding dengue vaccination. The scores for the Likert-like scale were as follows: 1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree somewhat; 3=neither agree nor disagree; 4=agree somewhat; and 5=strongly agree. A high score was given for the statement and the alternative answer defined as positive attitude; therefore, higher scores indicate a more positive attitude towards dengue vaccination.

2.5. Explanatory variables

2.5.1. Demographic data and personal history of past dengue fever

Some individuals will have a greater propensity to have an attitude towards vaccination, and the propensity is likely to vary with the basic demographic background. Therefore, data on age, gender, educational attainment, type of occupation, religion, marital status, monthly income and type of residence were also collected in this study. Age was recorded by date of birth and then converted into actual age. For education, the highest level of formal education completed was recorded. For occupation types, the dominant job was recorded when participants had multiple types of job. Five general types were used for classification: (1) farmer; (2) civil servant; (3) private sector employee; (4) entrepreneur who were working as traders in the traditional market or owned a small-scale business and (5) student or university student. Monthly income (the average amount of money earned each month) was assessed by asking the participants to choose the most suitable amount of money from a list provided. In addition, the participants' history of previous episodes of dengue fever, or family member(s) who had suffered from dengue fever, was also collected in this study.

2.5.2. Socioeconomic status (SES)

The ownership of fifteen indicator variables was used to construct an asset index based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) asproposed previously [11] with slight modification for the Indonesian and current context [12]. The indicator variables used were radio, refrigerator, bicycle, motorcycle, personal computer, internet connection, car, landline phone, pipedwater, flushed toilet, housing unit, and housing characteristics including having separate kitchen, non-dirt flooring, roof tiles, and brick walls. For measuring the asset index, the ownership of each asset item was given a score of one and zero otherwise. The asset index was constructed as the sum of the standardized asset scores multiplied by their respective factor loadings [12]. The quintiles of the asset index were calculated and households classified into 1st quintile (the poorest) to 5th quintile (the least poor).

Table 1 Characteristics of study participants and univariate logistic regression analysis showing predictors of attitude towards dengue vaccination (good vs. poor) (n=535).

2.5.3. KAP regarding dengue

A total of 28 questions adapted from previous studies [13, 14] was used to measure the knowledge regarding the signs and symptoms of dengue fever and the transmission of dengue viruses. The possible responses to all of the questions were “yes” or “no”; there was no“do not know” option. For each correct answer, a score of 1 was given while 0 was given for an incorrect answer. Higher scores thus indicate better knowledge.

A set of fifteen questions adapted from previous studies [12-14] was used to measure the attitude domain. Participants were asked to respond to the questions on a five-point Likert-like scale indicating their agreement regarding dengue ranging from ‘‘strongly agree'' to ‘‘strongly disagree''. The scores for the Likert-like scale were as follows: 1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree somewhat; 3=neither agree nor disagree; 4=agree somewhat; and 5=strongly agree. High score was given because the statement and the alternative answer defined as positive attitude.

To measure the preventive practices against dengue virus infection including preventing mosquito-man contact and eliminating mosquito breeding sites, sixteen questions were adopted from previous studies [13, 14]. Each valid response on a preventive measure was given a score of 1, whereas an incorrect response was given a score of 0. Higher scores therefore indicate better preventive practices regarding dengue virus transmission.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The assessment of attitude towards dengue vaccination and KAP domains was executed using a scoring system. Scores for each question were summed up to arrive at a single value out of a total score of 25 for attitude towards dengue vaccination. For KAP domains, scores for each question were also summed up to arrive at a single value out of a total score of 28, 75 and 16 for each KAP domain, respectively. In addition, attitude towards dengue vaccination and KAP domains were defined as ”good” or “poor”based on an 80% cut-off point [13].

To test the role of explanatory variables for the outcome variable, multi-step logistic regression analysis was used. In the first step, all explanatory variables (regency, age group, sex, education, occupation, religion, marital status, monthly income, type of resident, having family members with a history of dengue fever, having personally experienced dengue fever, SES and KAP domains) were included in univariate logistic regression analysis for attitude towards dengue vaccination. In the next step, significant explanatory factors from univariate analysis (P≤0.25) were entered into the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Confounding factors were explored as described previously [13].

In addition, the correlations between explanatory variables (SES and KAP scores) and attitude towards dengue vaccination were assessed using Spearman`s rank correlation (rs). The confidence intervals for rswere calculated as described previously [15]. This correlation was chosen because our data were not normally distributed as revealed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

3. Results

3.1. Demography

Table 1 summarizes the demographic data of 535 study participants surveyed in this study. Of the total participants, more than half were 17-29 years old and almost 70% were female. Approximately half of the participants had achieved educational levels higher than senior high school (12 years). One fourth of the participants were civil servants in government offices and 15% were farmers. More than 65% of the participants were living in suburbs. This may explain why half of the participants earned less than 1 million Indonesian Rupiah (US$81) per month. In Indonesia, in general, people living in the suburbs earn less money than the inhabitants of cities, and the majority of the farmer are living under the poverty line. Although only one tenth of the participants reported having had an episode of dengue fever, almost 20% of the participants had family member(s) who had suffered from dengue fever. This indicates a high prevalence of dengue virus infections in Aceh.

3.2. Modifiable determinants of attitude towards dengue vaccination

This study found that only 154 (28.7%) of 535 participants had a good attitude towards dengue vaccination against dengue viruses, with the highest and the lowest average scores in Langsa and Aceh Selatan, respectively (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in attitude towards dengue vaccination among regencies. Factors associated with a good attitude towards dengue vaccination were being female, having a high education level, working as a civil servant or private employee, having a high SES and a good KAP regarding dengue (P<0.05) (Table 1). Age, religion, marital status, monthly income, type of residence and personal experience or family member(s) with history of dengue fever had no association with the participants' attitude towards dengue vaccination.

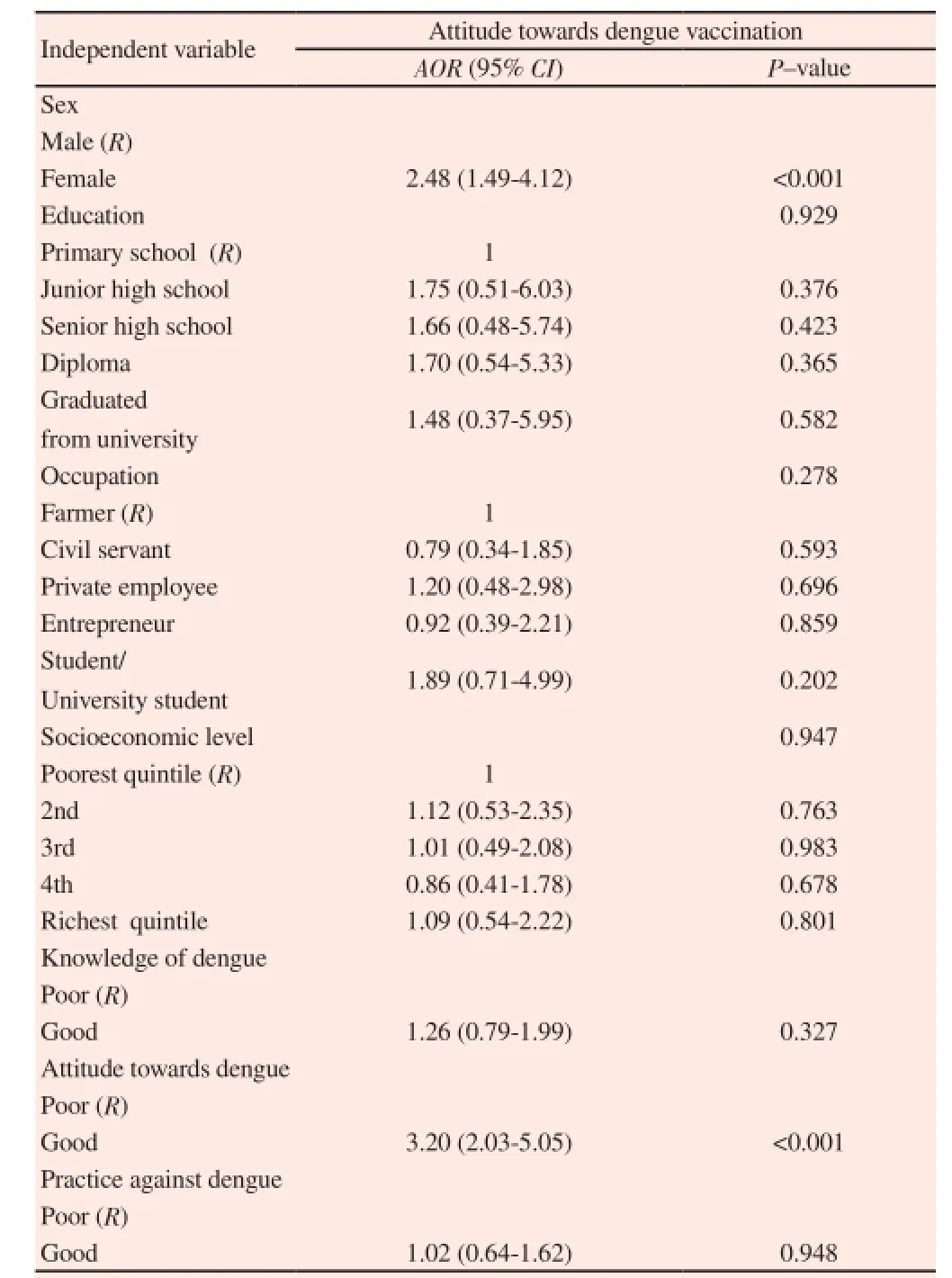

This study found that being female increased the odds of having a good attitude towards dengue vaccination by almost three times. Participants who had completed a diploma certificate and bachelor's degree had three times increased odds compared to participants who had completed primary school only (OR: 3.02; 95% CI: 1.08–8.40 and OR: 3.20; 95% CI: 1.17–8.76, respectively). Increased odds of having good attitude towards dengue vaccination were also observed among participants who were civil servants (OR: 2.07; 95% CI: 1.07–4.03) or working in the private sector (OR: 3.01; 95% CI: 1.48–6.13) compared to those who were farmers. In addition, participants who belonged to the richest quintile had two times higher odds of having good attitude towards dengue vaccination compared to the poorest quintile. In addition, good KAP domains were significantlyassociated with good attitude towards dengue vaccination. Each domain increased the odds of having a good attitude towards dengue vaccination approximately 2, 4 and 2 times, respectively, compared to participants who had poor KAP domains (OR: 2.17; 95% CI: 1.48–3.19, OR: 4.68; 95% CI: 3.12–7.03, and OR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.04–2.33, respectively). However, in multiple logistic regression analysis, our study found that only sex and attitude towards dengue were independent predictor factors for attitude towards dengue vaccination among the participants (Table 2).

3.3. Correlation between explanatory variables (index asset and KAP domain scores) and outcome variable

This study found that there was a significant positive correlation between asset index and attitude towards dengue vaccination (P<0.05) (Table 3). However, the correlation was very weak, rs=0.12. This confirms the previous logistic regression analysis which revealed that there was no strong correlation between asset index (socioeconomic levels) and attitude towards vaccination (Table 1). As expected, KAP domain scores were correlated strongly with attitude towards dengue vaccination, rs=0.25, rs=0.67 and rs=0.20, respectively (P<0.001). It is clear that the attitude domain is the strongest factor that is correlated with attitude towards dengue vaccination.

Table 2 Multiple logistic regression analysis showing predictors of attitude towards dengue vaccination (good vs. poor) (n=535).

Table 3 Multiple logistic regression analysis showing predictors of attitude towards dengue vaccination (good vs. poor) (n=535).

4. Discussion

Currently five dengue vaccine candidates are in human clinical trials and one vaccine, Sanofi Pasteur CYD-TDV, has completed Phase III trials in Latin American and Southeast Asian countries including Indonesia [9]. CYD-TDV was first licensed in Mexico and the Philippines in December 2015. As the dengue vaccination era is starting, it is high time to understand the attitude towards this vaccination and its associated factors among community members. This study was conducted to elucidate the community attitude towards dengue vaccination in Aceh, a province in Indonesia. In addition, this study also determined the potential modifiable determinants of attitude towards vaccination. The findings from this study might contribute basic data for formulating a suitable program for an accelerated introduction of dengue vaccines into communities of Aceh.

This study found the percentage of participants with good attitude towards dengue vaccination to be very low, less than 30%. In the univariate analysis, factors associated with a good attitude towards vaccination were being female and having good KAP domains regarding dengue. Additional factors such as high education level, certain types of occupation (working as civil servant or private sector employee) and high SES were also associated with good attitude towards vaccination. In a previous study we had found that types of occupation and education level were confounding factors of SES [16]. However, in the multiple logistic regression analysis reveals that only sex and attitude toward dengue were the independent predictor factors.

4.1. Factors associated with attitude towards dengue vaccination

Our study shows that a high education level is a promoter for vaccination. This finding is supported by extensive studies from countries as different as India [17], Pakistan [18], Greece [19] and the Netherlands [20]. Several studies also found that a low education level was a barrier for vaccination, e.g., in USA [21], India [22] and Kyrgyzstan [23].

Furthermore, our study also revealed that a high SES was associated with good attitude towards vaccination in Aceh. Although a study in Bangladesh found that people from both high and low SES had a favourable attitude towards vaccination [24]. Studies in India [25] and USA [26] reported that high SES was a promoter for vaccination. There are several ways in which a low SES can become a barrier for vaccination. For example, a low SES has been linked to issues of trust in healthcare providers [26] and is also related to both low education level and low access to vaccine [27]. Our study showed that a low SES was correlated with a low KAP regarding dengue in Aceh, and also correlated to lack of time to access information on dengue due to excessive working hours [28].

Our study revealed that both low knowledge and attitude regarding dengue as predictors for poor attitude towards vaccination but only attitude regarding dengue was identified as independent predictor (as shown in the multivariate analysis). A low knowledge could be a barrier for a dengue vaccination program. For example, a study in Nigeria found that poor maternal knowledge to be one of the factors that was related to low vaccination rates, and that poor knowledge was a more important barrier than cost of vaccination [29]. In addition, our previous studies revealed that there was a strong association between good attitude regarding dengue and good dengue preventive practices [28] and between good attitude regarding dengue and willingness to participate in dengue study [30] and that there was a good translation of attitudes into preventive practice [28].Therefore, we suggest that by improving the attitude towards dengue vaccination, the acceptance of a future dengue vaccination program will be increased.

In our study, being female increased odds of having good attitude towards vaccination more than two times than males in both univariate and multivariate analysis indicating effect of gender. Here, gender refers to socially constructed roles and responsibilities of males and females in the society. Similarly, response rate for participation and attitude towards dengue was also significantly higher among female participants in the study. These findings are consistent with findings from Nepal where higher attitude level among older female participants was reported [13]. Being female is more supportive i.e good attitude attitude towards both dengue and dengue vaccine which may be attributed to the major role of women in domestic works, collecting and storing water for domestic use, caring of ill members of the family including children and cleaning the breeding places of mosquitoes and to the fact that DENV vectors are primarily domestic and peri-domestic breeders. However, the results of our study must be interpreted with caution because the study was cross-sectional with enrollment of more than 70% female participants, assessed relationships based on one point in time and did not account for the dynamics of relationships between the factors analyzed. More importantly, it is possible that female participants might have provided socially desirable responses to attitude domain, since the survey was conducted by an interviewer-based use of a structured questionnaire.

4.2. Designing a dengue vaccine introduction program

To improve the attitude towards dengue vaccination among community members in Aceh, a vaccine introduction program should focus on particular groups of community members such as people with low SES, low educational level, farmers and entrepreneurs, and those with low KAP domains. Our previous study revealed that the factors associated with poor knowledge regarding dengue in Aceh were low education level, working as a farmer, low monthly income, low SES and living in the suburbs [28]. We could also confirm that education, occupation and monthly income are confounding factors of SES [28]. Therefore, these findings indicate that people who are working as farmers or entrepreneurs (traditional market traders), live in the suburbs of Aceh and have a low SES are the most appropriate priority target group for a dengue vaccine introduction program.

In the context of Aceh, and also in the majority of provinces in Indonesia, programs to improve the attitude towards dengue vaccination and dengue vaccine acceptance should be integrated with religious activities. Approximately 98% of the inhabitants of Aceh are Muslim, and it is compulsory for all adult males in Aceh to attend the Masjid (mosque) at least every Friday for praying . This local culture could be used to introduce the information related to dengue vaccination. This strategy has, at least, three advantages. First, it could be more convenient for people (related to their excessive working hours) compared to other methods such as seminars conducted either in district health centers or town halls. Second, most of the Acehnese people are very deeply religious Muslims and more likely to obey their religious leaders in the mosque than government health care workers (HCWs). Therefore, it might be easier to disseminate dengue vaccine information and increase the acceptance of dengue vaccine through well informed religious leaders. Third, such an approach is probably the most effective strategy to overcome religion-related issues surrounding dengue vaccination. Religionrelated issues have been reported to be among the most important barriers for vaccination in several countries [27], so minimizing their potential impact on dengue vaccination programs by involving religious leaders should be a priority.

Health care workers have a pivotal role in imparting information and advice to the public in the promotion of vaccines [29], and physicians are the principal and most influential source of vaccination information [30]. Therefore, the introduction of dengue vaccine to the public should also be delivered synergistically with a health centre-based strategy. In a previous study, we have advocated for a strategy called “one for five” [16], a health centre-based strategy to disseminate dengue related information (including on the dengue vaccination program) to dengue fever patients and their family. Each of them is then requested to disseminate this information to five other persons in their community. The idea behind this strategy is that dengue fever patients and their family members are much more likely to change their attitudes because they directly faced the dangers of clinically significant dengue virus infection. This idea is supported by a recent study showing that highlighting factual information about the dangers of communicable diseases could positively influence people's attitudes to vaccination [31].

To achieve satisfactory results using a health centre based strategy, both communicative skills of HCWs and comprehensiveness of information about dengue vaccination are crucial. These aspects would produce deeper understanding regarding dengue vaccination and increase the trust of community members in HCWs. Both comprehensiveness of information and trust are key to ensuring high vaccination rates. For example, comprehensiveness of vaccination information (e.g., knowledge about vaccine recommendation and time of vaccination) was shown to act as a promoter for vaccination [25]. Moreover, a review found that distrust of the community is an even more important factor for poor vaccination attitudes (hesitancy) than people being un-informed or misinformed [30]. Therefore, it is important to implement training courses regarding vaccination counseling to improve the understanding and communicative skills of HCWs.

Our study found that the percentage of healthy inhabitants of Aceh who have good attitude towards dengue vaccination is very low. Therefore, besides improving vaccine supply and strengthening provider capacity for quality service, improving community knowledge and attitude about dengue vaccination are two of the essential factors for the success of dengue vaccination programs. We recommend that the dengue vaccine introduction program in Aceh should be focused on a target group which encompasses community members in the suburbs with low SES such as farmers and traders in traditional markets. In the context of Aceh, two possible strategies are a religion based and a health centre based strategy. In both, a socialisation of dengue vaccine for debunking myths and rumors about vaccination, addressing religious issues and disseminating accurate and comprehensive information should be delivered, with good factual knowledge and communicative skills, to encourage community members to accept the dengue vaccine.

Acknowledgements

HH was responsible for study design, conducted study, data interpretation, and wrote the first draft and final manuscript. AB, AR, PA, RF, SS, RAB, AD, IA, MI, JA, FH, DD, RP and JKF collect and interpret the data. SA and AMS were responsible for data analyses, data interpretation, and revised first draft and final manuscript. UK, DAG, MLD, RTS, MD and RM were responsible for data interpretation, critically revised the first draft for intellectual content and wrote the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. HH is guarantor of the paper.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Guzman MG, Harris E. Dengue. Lancet 2015; 385(9966): 453-465.

[2] Shepard DS, Undurraga EA, Halasa YA. Economic and disease burden of dengue in Southeast Asia. PloS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7(2): 74-76.

[3] Karyanti MR, Uiterwaal CS, Kusriastuti R, Hadinegoro SR, Rovers MM, Heesterbeek H, et al. The changing incidence of dengue haemorrhagic fever in Indonesia: a 45-year registry-based analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14(1): 1-7.

[4] Kesehatan RI. Profil Kesehatan Indonesia Tahun 2014. Jakarta: Indonesia KKR; 2015.

[5] Kementerian RI. Dengue in Indonesia ituation and control. Jakarta: Kementrian Kesehatan RI; 2013.

[6] Kementerian RI. Profil kesehatan provinsi Aceh tahun 2012. Jakarta: Kementrian Kesehatan RI; 2015.

[7] Dinkes Aceh. Pemantauan kasus baru penyakit menular terpilih bulan Juni 2015. Banda Aceh: Dinas Kesehatan Aceh; 2015.

[8] DeRoeck D, Deen J, Clemens JD. Policymakers' views on dengue fever/ dengue haemorrhagic fever and the need for dengue vaccines in four southeast Asian countries. Vaccine 2003; 22(1):121-129.

[9] Capeding MR, Tran NH, Hadinegoro SR, Ismail HI, Chotpitayasunondh T, Chua MN, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of a novel tetravalent dengue vaccine in healthy children in Asia: a phase 3, randomised, observer-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 384(9951): 1358-1365.

[10] Lee JS, Mogasale V, Lim JK, Carabali M, Sirivichayakul C, Anh DD, et al. A multi-country study of the household willingness-to-pay for dengue vaccines: household surveys in Vietnam, Thailand, and Colombia. PloS Negl Trop Dis 2015; 9(6):e0003810.

[11] Filmer D, Pritchett L. The effect of household wealth on educational attainment: Evidence from 35 countries. Popul Dev Rev 1999; 25(1): 85-120.

[12] Hadisoemarto PF, Castro MC. Public acceptance and willingness-topay for a future dengue vaccine: a community-based survey in Bandung, Indonesia. PloS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7(9): 749-754.

[13] Dhimal M, Aryal KK, Dhimal ML, Gautam I, Singh SP, Bhusal CL, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding dengue fever among the healthy population of highland and lowland communities in central Nepal. PLoS One 2014; 9(7): e102028.

[14] Abdullah M, Azib W, Harun MFM, Burhanuddin MA. Reliability and construct validity of knowledge, attitude and practice on dengue fever prevention questionnaire. Am Inter J Contemp Res 2013; 3: 7.

[15] Bonett D, Wright T. Sample size requirements for Pearson, Kendall, and Spearman correlations. Psychometrika 2000; 65(1): 23-28.

[16] Harapan H, Anwar S, Setiawan A, Sasmono R, Aceh Dengue Study. Dengue vaccine acceptance and associated factors in Indonesia: A community-based cross-sectional survey in Aceh. Vaccine 2016; 34: 3670-3675.

[17] Rammohan A, Awofeso N, Fernandez RC. Paternal education status significantly influences infants' measles vaccination uptake, independent of maternal education status. BMC Public Health 2012; 12(1):1-7.

[18] Mitchell S, Andersson N, Ansari NM, Omer K, Soberanis JL, Cockcroft A. Equity and vaccine uptake: a cross-sectional study of measles vaccination in Lasbela District, Pakistan. BMC Int Health Human Rights 2009; 9 (Suppl 1):1-10.

[19] Danis K, Georgakopoulou T, Stavrou T, Laggas D, Panagiotopoulos T. Socioeconomic factors play a more important role in childhood vaccination coverage than parental perceptions: a cross-sectional study in Greece. Vaccine 2010; 28(7): 1861-1869.

[20] Uwemedimo OT, Findley SE, Andres R, Irigoyen M, Stockwell MS. Determinants of influenza vaccination among young children in an innercity community. J Community Health 2012; 37(3): 663-672.

[21] Stockwell MS, Irigoyen M, Martinez RA, Findley S. How parents' negative experiences at immunization visits affect child immunization status in a community in New York city. Public Health Rep 2011; 126(Suppl 2):24-32.

[22] Kumar D, Aggarwal A, Gomber S. Immunization status of children admitted to a tertiary-care hospital of north india: reasons for partial immunization or non-immunization. J Health Popul Nutr 2010; 28(3): 300-304.

[23] Akmatov MK, Mikolajczjk RT, Kretzschmar M, Kramer A. Attitudes and beliefs of parents about childhood vaccinations in post-soviet countries the example of Kyrgyzstan. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009; 28(7): 637-640.

[24] Rahman M, Obaida-Nasrin S. Factors affecting acceptance of complete immunization coverage of children under five years in rural Bangladesh. Salud Publica Mex 2010; 52(2): 134-140.

[25] Patra N. A probe into the ways to stimulate childhood immunization in India: finding from National Family Health Survey-III. Int J Child Adolescent Health 2012; 5: 65–84.

[26] Wu AC, Wisler-Sher DJ, Griswold K, Colson E, Shapiro ED, Holmboe ES, et al. Postpartum mothers' attitudes, knowledge, and trust regarding vaccination. Matern Child Health J 2008; 12(6):766-773.

[27] Antai D. Faith and Child Survival: The role of religion in childhood immunization in Nigeria. J Biosoc Sci 2009; 41(1):57-76.

[28] Harapan H, Anwar S, Bustaman A, Radiansyah A, Angraini P, Fasli R, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding dengue infection among healthy inhabitants in Aceh, Indonesia. Unpublished data.

[29] Babalola S. Maternal reasons for non-immunisation and partial immunisation in northern Nigeria. J Paediatr Child Health 2011; 47:276-281.

[30] Harapan H, Anwar S, Bustaman A, Radiansyah A, Angraini P, Fasli R, et al. Community willingness to participate in a dengue study in Aceh province, Indonesia. PloS One 2016; 11(7):e0159139.

[31] Tafuri S, Gallone MS, Cappelli MG, Martinelli D, Prato R, Germinario C. Addressing the anti-vaccination movement and the role of HCWs. Vaccine 2014; 32(38):4860-4865.

[32] Yaqub O, Castle-Clarke S, Sevdalis N, Chataway J. Attitudes to vaccination: a critical review. Soc Sci Med 2014; 112(4): 1-11.

[33] Horne Z, Powell D, Hummel JE, Holyoak KJ. Countering antivaccination attitudes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2015; 112(33): 10321-10324.

Document heading 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.07.036

20 June 2016

in revised form 20 July 2016

✉First and Harapan Harapan, Medical Research Unit, School of Medicine, Syiah Kuala University.

Tel./fax: +62 (0) 651 7551843

E-mail: harapan@unsyiah.ac.id

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Mechanism of action of Zhuyu Annao pill in mice with cerebral intrahemorrhage based on TLR4

- Effect of Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch polysaccharide on growth performance and immunologic function in mice in Ural City, Xinjiang

- Anti-tumor activity of tanshinone IIA in combined with cyclophosphamide against Lewis mice with lung cancer

- Acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase and paraoxonase 1 activities in rats treated with cannabis, tramadol or both

- Expression and mechanism of action of miR-196a in epithelial ovarian cancer

- Clinical significance of dynamic detection for serum levels of MCP-1, TNF-α and IL-8 in patients with acute pancreatitis