Current perspectives on dengue episode in Malaysia

2016-11-14EeLeenPangHweiSanLoh

Ee Leen Pang, Hwei-San Loh,2*

1School of Biosciences, Faculty of Science, The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Jalan Broga, 43500 Semenyih, Selangor, Malaysia

2Biotechnology Research Centre, The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Jalan Broga, 43500 Semenyih, Selangor, Malaysia

Current perspectives on dengue episode in Malaysia

Ee Leen Pang1, Hwei-San Loh1,2*

1School of Biosciences, Faculty of Science, The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Jalan Broga, 43500 Semenyih, Selangor, Malaysia

2Biotechnology Research Centre, The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Jalan Broga, 43500 Semenyih, Selangor, Malaysia

Accepted 15 March 2016

Available online 20 April 2016

Dengue

Antibody-dependent enhancement

Pandemic

Vaccine

Malaysia

To Prevalence of dengue transmission has been alarmed by an estimate of 390 million infections per annum. Urban encroachment, ecological disruption and poor sanitation are all contributory factors of increased epidemiology. Complication however arises from the fact that dengue virus inherently exists as four diff erent serotypes. Secondary infection is often manifested in the more severe form, such that antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) could aggravate ailment by allowing pre-existing antibodies to form complexes with infecting viruses as means of intrusion. Consequently, increased viraemic titter and suppression of antiviral response are observed. Deep concerns are thus expressed in regards to escalating trend of hospitalisation and mortality rates. In Malaysia, situation is exacerbated by improper clinical management and pending vector control operations. As a preparedness strategy against the potential deadly dengue pandemic, the call for development of a durable and costeff ective dengue vaccine against all infecting serotypes is intensifi ed. Even though several vaccine candidates are currently being evaluated in clinical trials, uncertainties in regards to serotypes interference, incomplete protection and dose adequacy have been raised. Instead of sole reliance on outsourcing, production of local vaccine should be considered in coherent to government’s eff orts to combat against dengue.

1. Introduction

The alarming rise of dengue epidemiology has been highlighted to haunt 40% of world population; where disease severity varies from asymptomatic infection to undiff erentiated dengue fever (DF) or possibly develop into life-threatening manifestations such as dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS)[1]. Classifi ed under the Flaviviridae virus family, dengue virus (DENV)presents itself as a 500Å single-stranded, positive-sense nonsegmented RNA virus[2]. Size of the virus genome is approximately 10.6 kilo-base pairs (kbp) long; encoding a single polypeptide which will be processed by serine protease into structural proteins, namely capsid (C); envelope glycoprotein (E); precursor membrane (prM))and non-structural biomolecules (NS1, 2A, 2B, 3, 4A, 4B and 5)[3]. During assembly, the highly-basic C protein will encapsidate the viral RNA to form nucleocapsid particles while prM assists the folding of surface-exposed E glycoprotein, with both integrated into the lipid bilayer[4].

Hitherto, transmission of the endemic virus has been reported in more than 100 countries. Incidence rate has expanded by 500-fold, spreading from South-east Asia to Americans and Western Pacific merely within a-half century[5]. Global distribution of dengue disease is strongly infl uenced by urbanisation, demographic and environmental factors. Cumulative concerns are also driven by increased travel of tourists and military personnel[6]. Based on the 50-100 million of cases reported annually, an average of 500 000 patients are hospitalised with DHF and DSS where 22 000 deaths are primarily among children[7-8]. Yet, recent study reported startling estimates of dengue burden that triples past predictions, where 390 million infections were mapped per annum[9]. The eff ect from global warming has also made it possible for Aedes mosquitoes to survive beyond its current distribution and further promotes the spread of virus. In fact it was projected that by 2080s, over 5-6 billion of world population may be exposed to risk of infection due to climate change and population growth[10].

Pathogenesis

Humans are infected through the bite of Aedes mosquitoes that usually breed in domestic water containers. Abrupt fever accompanied by anorexia, headache, myalgia, retro-orbital pain and occasionally rashes are symptoms of classical DF within 4 to 7 days of febrile period[11]. Onset of critical DHF and DSS usually emerges during time of defervescence where increased propensity of capillary leakage is observed prior hypovolemic shock[12]. As infecting virus is being circulated in the peripheral blood of patients, a mosquito’s bite during febrile viraemic stage would result in disease being transmitted to another host after an extrinsic incubation period[13]. DHF is commonly diagnosed with haemorrhagic bleeding,thrombocytopenia and increased fl uid eff usion in addition to typical DF symptoms; while DSS is presented by weak pulse and pressure,where profound shock may set in and lead to death within 12 to 36 hours[11].

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is deployed as the cell entry mechanism during initial infection. Upon binding of the viral particle to the cellular receptor, clathrin-coated pit will capture the complex and then pinch off into cell cytoplasm[14]. During secondary infection, complexes are formed between replicating viruses and non-neutralising antibodies induced by previous infection or even derived from maternal IgG to usurp Fc-γ receptors as mode of entry[15]. This phenomenon is denoted as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). Upon entry, the vesicles move through the endosomes until conformational change is triggered by acidifi cation which ultimately releases the uncoated single-stranded viral RNA into cytosol[16]. Translation of viral genetic material proceeds at rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER) before membrane is invaginated to form vesicles for RNA replication. Following virus budding into ER lumen, progeny virions are packed and transported to trans-Golgi complex for prM cleavage by cellular furin protease prior releasing mature virions through constitutive secretory pathway[17].

Feeding of disease carrier presumably introduces DENV into the bloodstream, where Langerhans cells are targeted followed by local replication of virus. Infected dendritic cells then undergo maturation and migrate towards the lymph nodes to target monocytes and macrophages[18]. Infection is amplifi ed through the dissemination of virus in lymphatic system[11]. In the context of dengue pathogenesis, subversion of host immunity is achieved by hijacking host cellular machineries to promote infection. The virus adaption tricks are summarised as follow: (i) induction of autophagy via unfolded protein response to trigger production of double membrane vesicles as viral replication platform; (ii) mobilisation of triglyceride by lipophagy to produce energy for viral assembly; and(iii) sequestration of stress granules to prevent stalling of mRNA translation[19]. Albeit association of ailment aggravation to ADE still remains elusive, compiling evidences are now highlighting its cytotoxic outcome based on increased viraemic titre and /or modulation of immunosuppressive events to alter conduciveness of local milieu for viral replication[12]. In fact, it has been proven that ADE is the strongest risk factor of DHF/DSS development when severe illness is suffered by seropositive patients[20]. It was also emphasised that the risk of acquiring DHF in secondary infections was 40 times signifi cantly higher than primary cases[19]. Prevalence and epidemiology

Transmission cycles of DENV are observed from two phenomena:(i) sylvatic cycle of canopy-dwelling Aedes mosquitoes that infect non-human primates in rain forest habitats of Asia and Africa; and(ii) infection of human hosts by A. aegypti (primary vector) and/or A. albopictus that circulate in urban and peri-urban environments of tropics[21]. Interestingly, DENV isolates in most urban centres are evolved from sylvatic progenitors approximately 100-1500 years ago[22]. It is also believed that structural changes of the domain III of DENV E protein (EDIII) have prompted adaptation to new peridomestic vectors that led to resurgence of the arbovirus. Albeit the earliest record of epidemics could be traced back to 1780-1940, yet, it was the ecological disruption during World War II that intensified disease transmission in South-East Asia and Pacifi c[21]. In parts of Central and South American, the collapse of A. aegypti eradication campaign during early 1970s had set a scene of re-infestation and hyperendemicity followed due to increased circulation of viral serotypes into these areas[23]. Escalating movement of dengue virus into new territories had been mapped,where geographical spread of diff erent subtypes was signifi cantly noted in the last two decades, particularly in Asia and Latin America[24]. Contemporary understanding of the distribution pattern of DENV should be underlined in terms of providing insights to disease management and clinical research.

History of dengue in Malaysia

In Malaysia, onset of dengue infection was dated back in year 1901 following transmission from Singapore to Penang[25]. First epidemic outbreak was then alarmed in 1973, recording a total of 969 cases and 54 deaths[26]. The condition continued to worsen thereafter, with increasing disease infestation among urban dwellers throughout the nation[27]. Taxonomically, the causative agent is an icosahedral virus that manifests as four distinct subtypes (DENV1-4) with 65-70% sequence homology[28]. Not surprisingly, all serotypes were found to be co-circulating in Malaysia. For instance, DENV1, DENV2 and DENV3 were identifi ed in Negeri Sembilan[29], multiple entries of DENV2 and DENV4 in Sarawak[30] while DENV4 dominated the populated regions of Kuala Lumpur and Selangor[31]. It was suggested that severity of disease outbreak could be predicted based on the predominant serotype at one point[32]. Such correlation was also proven by other fi ndings, whereby intense illness was observed in patients suffering from primary infection of DENV1 or DENV3 whereas infestation by DENV2 in secondary case would further aggravate ailment with DHF[33,34]. Generally all gender and ethnic groups are equally vulnerable to dengue infection. In South-East Asia, severe DHF/ DSS cases are predominant among paediatricpatients aged between 2-15 years[35]. However, a shift of disease pattern inclining towards adult population has been highlighted recently. In Malaysia, majority of the aff ected community are now identifi ed as the age group of 13-35 years old[36]. In fact, high dengue IgG seropositivity (91.6%) had been detected among Malaysian adults despite of localities[37]. On annual basis, economic burden of USD $56 million had been allocated as disease management fees[38]. This is the dengue episode which causes impact on most health domains, leading to 60% loss in quality of life (QoL) in the worst scenario[39].

Current statistics and disease management

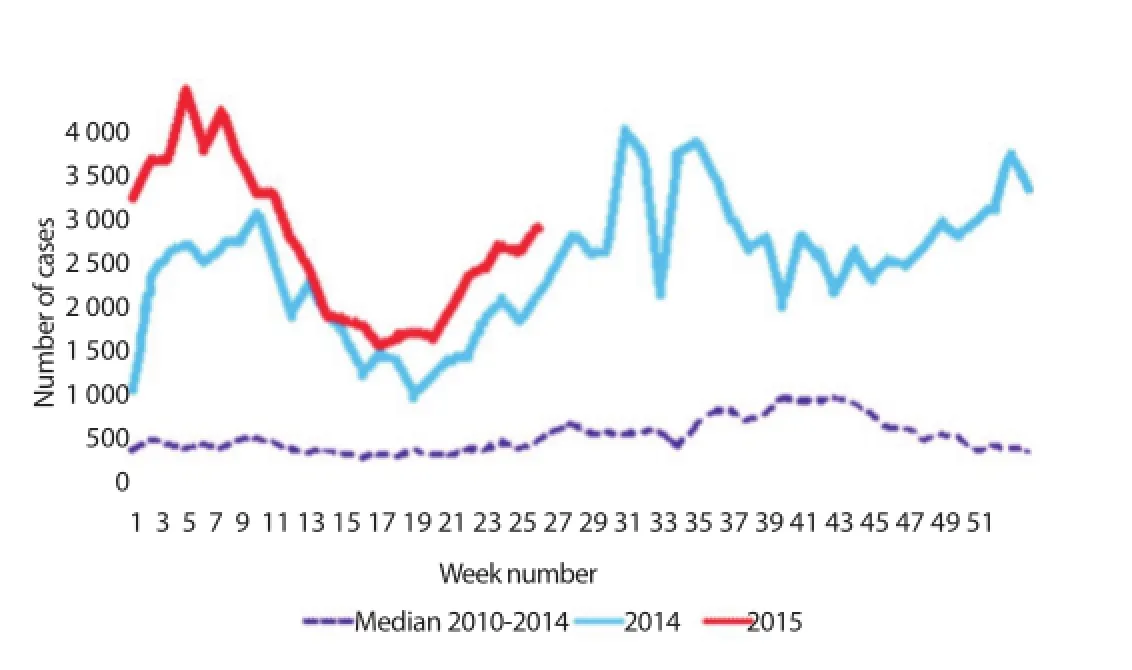

In Malaysia, dengue is perceived as a highly contagious health threat with escalating trend of infection. The average number of dengue cases and death tolls had recorded a surge of 14% and 8%,respectively per annum, over the years of 2000-2010[40]. Even worse, Malaysia had suff ered an increment of 250% infections in 2014 alone as shown in Figure 1[41,42]. Based on the latest record,a total number of 59 866 dengue cases and 165 deaths had been reported merely within the fi rst half of the year (updated on 6th July 2015). Comparing the disease trend in Malaysia (see Figure 2[42]),it is predictable that dengue will continue to hog nation headlines with record breaking levels if no eff ective control operations are enforced. Situation may only get worse in the upcoming months as cases usually peak in the spell of wet weather during monsoon season. With 10 000 people contracting the disease every month, it can progress into more intense scenario as seroprevalence of dengue antibodies is contributing to high fatality rate when associated with ADE during secondary infection. Considering the number of underreported cases, the data may not refl ect the absolute fi gure due to low public awareness and passive surveillance system. This signifi es that dengue episode in Malaysia is under the solemn pressure of reaching a pandemic level.

Figure 1. Statistical number of dengue cases reported within the period 2000-2014. Data sourced from Malaysian Remote Sensing Agency (ARSM)/ Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI)[41] and World Health Organization Western Pacifi c Region (WPRO)[42].

Figure 2. A comparative graph showing the trend of dengue infections in Malaysia; translated from Malay to English translation. Diagram modifi ed from WPRO[42].

The ‘oldfolk’ remedies

Hitherto, no specifi c medication is available for dengue treatment. Current clinical practices mainly rely on administration of paracetamol and isotonic intravenous fluids apart from close monitoring of blood glucose and platelet levels[43]. However,fl uid overload could complicate situation when patient care is not judiciously monitored; which might lead to circulatory failure in its most severe form. Concern was raised as high percentage of deaths correlated to fl uid overload[44], thereby refl ecting the competency gap in clinical management. Moreover, the lack of vaccine or suitable drug has driven public’s reliance on traditional remedies that are mostly not scientifi cally proven. Common practices include decoction of tawa-tawa leaves, bitter gourd and preparation of papaya leaves. Caution must be considered as over-dosage of certain plant extracts may be toxic. For instance, toxicological studies of tawa-tawa extract (Euphorbia hirta) had confi rmed its genotoxic and cytotoxic properties[45, 46]. A list of medicinal plants with tested antidengue activity had been summarised by Abd Kadir et al.[47].

Aedes mosquitoes control regimes

Under such circumstances, the only available option to curb the disease relies on vector control programmes. Yet, regimes in practice such as insecticidal treatment and fogging have failed to produce expected disease containment owing to high cost and limited eff ectiveness[48]. Understanding the seasonal cycle of disease transmission provides a fundamental basis to guarantee a success of vector control. For instance, fogging can be scheduled at the peak biting time especially in the advent of rainy season. Nevertheless, it should be noted that extensive applications might adversely prompt the emergence of insecticide-resistant mosquitoes. The eff ectiveness of permethrin (a broad spectrum pyrethroid insecticide whichis widely employed for vector control programme in Malaysia)was questionable when a collection of field strains from Kuala Lumpur had shown to exhibit up to 5.57 folds of resistance[49]. Such preventive practices were also hampered by public’s underestimation of the susceptibility to dengue infection and the lack of concerted community eff orts[50]. Their inattentive behaviour in maintaining good sanitation (e.g. reduce Aedes breeding grounds) and reliance on health authority are community challenges that need serious attention; this possibly can be overcome upon adopting the Communication for Behavioural Impact (COMBI) approach by World Health Organization[51].

A new vector suppression technology (i.e. Release of Insects with Dominant Lethality, RIDL) was adopted by the Malaysia government in December 2010. It involved releasing geneticallymodifi ed (GM) mosquitoes into the uninhabited forest of Pahang. The sterile male A. aegypti (OX513A) was manipulated to harbour dominant lethal transgene insertion and compete with wild-type male for mating. High expression of the lethal factor in a positive feedback loop would then limit the survival of transgenics by 95-97% at latelarval or early-pupal stage[52]. The ultimate aim is to reduce the target population involved in disease transmission. Albeit the fi tness of modifi ed strain was not aff ected in the open fi eld settings, the data obtained was inconclusive to demonstrate vector suppression as the release site was far beyond their natural habitats (urbanised area)for mating[48]. Future operational use of the modifi ed strain would be supported if similar observation could be collected as that of the fi eld trial in Cayman Islands[53]. On the other hand, Wolbachiabased biocontrol was exploited by Australia through transinfection of A. aegypti. In such approach, dengue transmission is suppressed through sabotage of vector breeding via cytoplasmic incompatibility and also shortens virus lifespan by blocking viral replication in mosquitoes’ salivary gland[54]. The Wolbachia invasion strategy had pulled off a successful ‘proof-of-concept’, where fi xation of bacteria in the wild mosquito population was observed after three months[55]. Still, the paradigm of Wolbachia release requires further monitoring on the direct test of effi cacy. Predictions are made whereby dengue could mutate to acquire stronger virulence and/or partially escape the transmission blockage; while evolution of Wolbachia at its fi tness cost is possible since life-shortening property is also limiting bacterial establishment[56]. So far, fi eld trials of releasing Wolbachiainfected mosquitoes have begun in dengue endemic areas (i.e. Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia and Vietnam) where formal assessment of epidemiological protection can be done[57]. Worthwhile to mention, a lesson should be learnt from the public backlash against release of GM mosquitoes in Malaysia. This is because community engagement is indispensable to gauge support and promote the implementation of a new programme.

Future direction: vaccine development

Waves of dengue vaccine development have increased dramatically over the decade, aiming to pursue the unmet medical need of tropical and sub-tropical urban dwellers. Looking into the stateof-art of vaccine development, competition on pioneering rights to license an immunoprotective dengue vaccine has been progressing aggressively among organisations like Sanofi Pasteur, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Naval Medical Research Center, John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and so on. Although live attenuated vaccines are the most clinically evaluated along the pipeline[58], potency of other vaccine candidates generated as whole inactivated virus[59], recombinant subunit protein[60] and DNA-based vaccine[61] are also undertaking clinical trials. Despite that, it was predicted that none will be released for community distribution by year 2015[62].

While active researches are ongoing, resolving questions on the flavivirus biology and immunopathogenesis still remain as the key challenges. Problem to be addressed is even reflected from Sanofi’s vaccine candidate. Albeit ChimeriVax-Dengue (CYD)is advancing to the finish line, serotypes interference has been reported. Competition of in vivo viral replication and epitopes-linked immunodominance were noted when the vaccine was administrated as tetravalent formulation[63]. Imbalance viral replication among the four monovalent serotypes was perceived as a threat that could jeopardise the desired level of immunoprotectivity[64]. The phase 2b clinical trial conducted in Thailand revealed that CYD did not off er protection against DENV2 infection even after three doses[65]. The possibility of antigenic mismatch between CYD2 vaccine design and DENV2 was ruled in as the factor that could diminish the overall protection effi cacy[66]. Based on the recent phase 3 clinical trials, the vaccine efficacy for serotype 2-specific still remained as the lowest[67]. Despite with proven efficacy, more conclusive data on its tetravalency protection should be properly assessed in epidemiological settings. Also, it is a concern if Sanofi can only off er 100 million doses of fi rst vaccine; it is unable to deliver immediate reliefs with 3 billion of world populaces who are at stake of risk[68]. In terms of subunit vaccine production, dengue E protein has been the most targeted antigenic determinant. Its structure is organised into three ectodomains (I-III), serves to assist attachment and entrance into host cells via receptors like heparin sulphate[69]. In fact, it is the immunoglobulin-like EDIII that harbours the receptor binding motif to elicit neutralising monoclonal antibodies[70]. The selection of EDIII as the serotype-specific antigenic determinant was consolidated by Block et al.[71], stating that other structural proteins (i.e. EDI/II and prM) were associated with ADE despite having (weak) neutralisation capacity. The stand-alone stability of domain III also made it intrinsically different from other parts of the glycoprotein[72]. In several studies, EDIII was expressed as the consensus sequence aligned between four DENV serotypes[73-76],designated as cEDIII. This is justified based on the requirement for cross-neutralisation in order to confer full immunisation against all serotypes. In fact, the mice immunological data from Leng et al.[73] demonstrated that cEDIII was able to block viralinfections from four serotypes simultaneously. Due to the fact that wild-type mice are naturally-resistant to dengue infections,further challenge studies with non-human primates is thought to be more reliable. However, recent experimentation by Chen et al.[77]reported macaques’ seroconversion was obtained but unlikely only against DENV serotype-2. It was explained by the diff erent epitope recognition site harboured by neutralising antibodies elicited in different species model. If cEDIII-based antigen is proven to be useful, it could benefi t from being stumbled by immune interference issue. Moreover, in consideration of virus mutation and lineage replacement is possible[78,79], development of a long-term protective vaccine is imperative.

Local vaccine development would have a momentous impact in Malaysia as, up to date, there are (i) no licensed dengue vaccine available globally; (ii) no successful vector control regimes to hamper rapid proliferation of A. aegypti especially in remote areas;and (iii) no published or patented use of local isolates as tetravalent vaccine candidate. Recording an annual estimate of USD $238 million economic burden in countries within South America and South-East Asia, projection is made that as discovery of dengue vaccine ratchets up, the potential market could capture an astounding value of USD $2-21 billion in near future[80, 81]. Inundated with escalating dengue outbreaks that raged through local patients, the protection off ered by established vaccine is anticipated to guard public health, in line with the government’s eff ort to combat the spread of dengue through release of genetically-modifi ed mosquitoes and reinforced sanitary measures.

Conclusion

To battle the upsurge of disease burden implicated in ambulatory and medical settings, there is an urgent call to deliver a durable and eff ective pharmaceutics as no licensed vaccine is available to date. This is in consideration that dengue endemic is predominantly suffered by under-developed nations including Malaysia. Collaborative eff orts between dengue vaccine research groups and government health agencies are imperative to make a signifi cant contribution in dengue control, without under-estimating the risk underlying this potentially fatal global threat.

[1] Murrell S, Wu SC, Butler M. Review of dengue virus and development of a vaccine. Biotechnol Adv 2011; 29: 239-247.

[2] Kuhn RJ, Zhang W, Rossmann MG, Pletnev SV, Corver J, lenches E, et al. Structure of dengue virus: Implications for fl avivirus organization,maturation, and fusion. Cell 2002; 108(5): 717-725.

[3] Henchal EA, Putnak JR. The dengue viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev 1990;3(4): 376-396.

[4] Whitehead SS, Blaney JE, Durbin AP, Murphy BR. Prospects for a dengue virus vaccine. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007; 5(7): 518-528.

[5] Kyle JL, Harris E. Global spread and persistence of dengue. Ann Rev Microbiol 2008; 62: 71-92.

[6] Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, Fisk Tamara, Robins Rachel,Sonnenburg Frank von, et al. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned visitors. The New England J Med 2006;354(2): 119-130.

[7] Rigau-Pérez JG, Clark GG, Gubler DJ, Reiter P, Sanders EJ, Vorndam AV. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. The Lancet. 1998;352(9132): 971-977.

[8] World Health Organization. Impact of dengue. global alert and response(GAR).[Online] Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/dengue/ impact/en/[Accessed 15th March 2015].

[9] Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature[Online] 2013;496: 504-507. Available from doi: 10.1038/nature12060.[Accessed 10th April 2014].

[10] Hales S, de Wet N, Maindonald J, Woodward A. Potential effect of population and climate changes on global distribution of dengue fever: an empirical model. The Lancet 2002; 360(9336): 830-834.

[11] Martina BE, Koraka P, Osterhaus AD. Dengue virus pathogenesis: an integrated view. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009; 22(4): 564-581.

[12] Whitehorn J, Simmons CP. The pathogenesis of dengue. Vaccine 2011;29(42): 7221-7228.

[13] Guzman MG, Halstead SB, Artsob H, Buchy Philippe, Farrar Jeremy,Gubler DJ, et al. Dengue: a continuing global threat. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010; S7-S16. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2460.

[14] van der Schaar HM, Rust MJ, Chen C, van der Ende-Metselaar H,Wilschut Jan, Zhuang XW, et al. Dissecting the cell entry pathway of dengue virus by single-particle tracking in living cells. PLOS Pathog[Online] 2008; 4(12): e1000244. Available from doi: 10.1371/ journal.ppat.1000244.[Accessed 12th May 2014].

[15] Wang X, Huang X, Wang S. Study on immunity of dengue virus and dengue vaccine development. Front Biol China 2009; 4(2): 125-128.

[16] Green AM, Beatty PR, Hadjilaou A, Harris E. Innate immunity to dengue virus infection and subversion of antiviral responses. J Mole Biol 2004;426(6): 1148-1160.

[17] Welsch S, Miller S, Romero-Brey I, Merz Andreas, Bleck CKE, Walther P, et al. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host & Microbe 2009; 5(4): 365-375.

[18] Marovich M, Grouard-Vogel G, Louder M, Eller M, Sun Wellington, Wu SJ, et al. Human dendritic cells as targets of dengue virus infection. J Invest Derm Symp P 2001; 6(3): 219-224.

[19] Jain B, Chaturvedi UC, Jain A. Role of intracellular events in the pathogenesis of dengue: An overview. Microb Pathogenesis 2014; 69-70: 45-52.

[20] Kliks SC, Nisalak A, Brandt WE, Wahl L, Burke DS. Antibodydependent enhancement of dengue virus growth in human monocytes as a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am J Trop Med and Hyg1989; 40(4): 444-451.

[21] Gubler DJ. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998; 11(3): 480-496.

[22] Wang E, Ni H, Xu R, Barrett AT, Watowich SJ, Gubler DJ, Weaver SC. Evolutionary relationships of endemic/epidemic and sylvatic dengue viruses. J Virol 2000; 74(7): 3227-3234.

[23] Gubler DJ. Resurgent vector-borne diseases as a global health problem. Emerging Infect Dis 1998; 4(3): 442-450.

[24] Messina JP, Brady OJ, Scott TW, Zou CT, Pigott DM, Duda KA, et al. Global spread of dengue virus types: mapping the 70 year history. Trends Microbiol 2014; 22(3): 138-146.

[25] Skae FM. Dengue fever in Penang. Brit Med J 1902; 2: 1581-1582.

[26] Wallace HG, Lim TW, Rudnick A, Knudsen AB, Cheong WH, Chew V. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in Malaysia: the 1973 epidemic. The Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1980; 11(1): 1-13.

[27] AbuBakar S, Norazizah S. Outlook of dengue in Malaysia: a century later. The Malaysian J Pathol 2002; 24(1): 23-27.

[28] Rico-Hesse R. Molecular evolution and distribution of dengue viruses type 1 and 2 in nature. Virology 1990; 174(2): 479-493.

[29] Ahmad Nizal MG, Rozita H, Mazrura S, et al. Dengue infections and circulating serotypes in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Malaysi J Public Health Med 2012; 12(1): 21-30.

[30] Holmes EC, Tio PH, Perera D, Muhi J, Cardosa J. Importation and cocirculation of multiple serotypes of dengue virus in Sarawak, Malaysia. Virus Res 2009; 143(1): 1-5.

[31] Chew MH, Rahman MM, Jelip J, Hassan MR, Isahak I. All serotypes of dengue viruses circulating in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Curr Res J Biol Sci 2012; 4(2): 229-234.

[32] Lam SK. Two decades of dengue in Malaysia. Trop Med 1993; 35(4): 195-200.

[33] Vaughn DW, Green S, Kalayanarooj S, Innis BL, Nimmannitya S,Suntayakorn S, et al. Dengue viremia titer, antibody response pattern, and virus serotype correlate with disease severity. J Infect Dis 2000; 181(1): 2-9.

[34] Fried JR, Gibbons RV, Kalayanarooj S, Thomas SJ, Srikiatkhachorn A, Yoon IK, et al. Serotype-specific differences in the risk of dengue hemorrhagic fever: An analysis of data collected in Bangkok, Thailand from 1994 to 2006. PLOS Negl Trop Dis[Online] 2010; 4(3): e617. Available from doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000617.[Accessed 23rd May 2014].

[35] Bhatia R, Dash AP, Sunyoto T. Changing epidemiology of dengue in South-East Asia. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health 2013; 2(1): 23-27.

[36] Sam SS, Omar SF, Teoh BT, Abd-Jamil J, AbuBakar S. Review of dengue hemorrhagic fever fatal cases seen among adults: A retrospective study. PLOS Negl Trop Dis [Online] 2013; 7(5): e2194. Available from doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002194.[Accessed 26th May 2014].

[37] Muhammad Azami NA, Salleh SA, Neoh HM, Syed Zakaria SZ, Jamal R. Dengue epidemic in Malaysia: Not a predominantly urban disease anymore. BMC Res Notes [Online] 2011; 4: 216. Available from doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-216.[Accessed 26th May 2014].

[38] Shepard DS, Lees R, Ng CW, Undurraga EA, Halasa Y, Lum L. Burden of dengue in Malaysia. Report from a collaboration between universities and the Ministry of Health of Malaysia. Brandeis University, Schneider Institutes for Health Policy, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, University of Malaya. Report version: 50, 2013.

[39] Lum LC, Suaya JA, Tan LH, Sah BK, Shepard DS. Quality of life of dengue patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008; 78(6): 862-867.

[40] Mia MS, Begum RA, Er AC, Abidin RD, Pereira JJ. Trends of dengue infections in Malaysia, 2000-2010. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2013; 6(6): 462-466.

[41] Malaysian Remote Sensing Agency (ARSM), Ministry of Science,Technology and Innovation (MOSTI). Dengue untuk komuniti.[Online]Available from: http://idengue.remotesensing.gov.my/idengue/index. php[Accessed 6th July 2015].

[42] World Health Organization Western Pacifi c Region (WPRO). Emerging disease surveillance and response: Dengue situation update number 468.[Online] Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/emerging_diseases/ DengueSituationUpdates/en/[Accessed 6th July 2015].

[43] World Health Organization (WHO), Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR). Dengue: Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control - New edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

[44] Cheah WK, Ng KS, Marzilawati AR, Lum LC. A review of dengue research in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia 2014; 69: 59-67.

[45] Rajeh MA, Kwan YP, Zakaria Z, Latha LY, Jothy SL, Sasidharan S. Acute toxicity impacts of Euphorbia hirta L extract on behaviour, organs body weight index and histopathology of organs of the mice and Artemia salina. Phcog Res 2012; 4(3): 170-177.

[46] Kwan YP, Darah I, Chen Y, Sasidharan S. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity assessment of Euphorbia hirta in MCF-7 cell line model using comet assay. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2013; 3(9): 692-696.

[47] Abd Kadir SL, Yaakob H, Mohamed Zulkifli R. Potential anti-dengue medicinal plants: a review. J Nat Med 2013; 67(4): 677-689.

[48] Lacroix R, McKemey A, Raduan N, Wee LK, Ming WH, Ney TG, et al. Open fi eld release of genetically engineered sterile male Aedes aegypti in Malaysia. PLOS One[Online] 2012; 7(8): e42771. Available from doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042771.[Accessed 28th May 2014].

[49] Wan-Norafikah O, Nazni WA, Lee HL, Zainol-Ariffin P, Sofian-Azirun M. Permethrin resistance in Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus) collected from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J Asia-Pac Entomol 2010; 13(3): 178-182.

[50] Wong LP, AbuBakar, S. Health beliefs and practices related to dengue fever: A focus group study. PLOS Negl Trop Dis [Online] 2013; 7(7): e2310. Available from doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002310.[Accessed 28th May 2014].

[51] Shafie FA, Mohd Tahir MP, Sabri NM. Aedes mosquitoes resistance in urban community setting. Procedia - Social Behav Sci 2012; 36: 70-76.

[52] Phuc HK, Andreasen MH, Burton RS, Vass C, Epton MJ, Pape G, et al. Late-acting dominant lethal genetic systems and mosquito control. BMC Biol [Online] 2007; 5: 11. Available from doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-11.[Accessed 28th May 2014].

[53] Harris AF, Nimmo D, McKemey AR, Kelly N, Scaife S, Donnelly CA,et al. Field performance of engineered male mosquitoes. Nat Biotechnol 2011; 29: 1034-1037.

[54] Walker T, Johnson PH, Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Frentiu FD,McMeniman CJ, et al. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature 2011; 476: 450-453.

[55] Ritchie S. Rear and release: a new paradigm for dengue control. Austral Entomol 2014; 53(4): 363-367.

[56] Bull JJ, Turelli M. Wolbachia versus dengue: Evolutionary forecasts. Evol, Med Public Health[Online] 2013; 197-207. Available from doi: 10.1093/emph/eot018.[Accessed 28th May 2014].

[57] Nogrady B. Bacteria put the bite on mozzies.[Online]. Available from: http://www.monash.edu.au/monashmag/articles/issue8/bacteria-put-thebite-on-mozzies.html#.Vb5TbvNViko[Accessed 28th March 2015].

[58] Guy B, Saville M, Lang J. Development of Sanofi Pasteur tetravalent dengue vaccine. Hum Vaccines 2010; 6(9): 696-705.

[59] Sun W, Edelman R, Kanesa-Thasan N, Eckels K, Putnak JR, King AD. Vaccination of human volunteers with monovalent and tetravalent liveattenuated dengue vaccine candidates. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003; 69(6): 24-31.

[60] Robert Putnak J, Coller BA, Voss G, Vaughn DW, Clements D, Peters I,et al. An evaluation of dengue type-2 inactivated, recombinant subunit,and live-attenuated vaccine candidates in the rhesus macaque model. Vaccine. 2005; 23(5): 4442-4452.

[61] Raviprakash K, Ewing D, Simmons M, Porter KR, Jones TR, Hayes CG, et al. Needle-free Biojector injection of a dengue virus type 1 DNA vaccine with human immunostimulatory sequences and the GM-CSF gene increases immunogenicity and protection from virus challenge in Aotus monkeys. Virology 2003; 315(2): 345-352.

[62] Guy B, Barrere B, Malinowski C, Saville M, Teyssou R, Lang J. From research to phase III: preclinical, industrial and clinical development of the Sanofi Pasteur tetravalent dengue vaccine. Vaccine. 2011; 29(42): 7229-7741.

[63] Guy B, Barban V, Mantel N, Aguirre M, Gulia S, Pontvianne J et al. Evaluation of interferences between dengue vaccine serotypes in a monkey model. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009; 80(2): 302-311.

[64] Imoto J, Konishi E. Dengue tetravalent DNA vaccine increases its immunogenicity in mice when mixed with a dengue type 2 subunit vaccine or an inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine. Vaccine 2007;25(6): 1076-1084.

[65] Halstead SB. Identifying protective dengue vaccines: Guide to mastering an empirical process. Vaccine 2013; 31(41): 4501-4507.

[66] Sabchareon A, Wallace D, Sirivichayakul C, Limkittikul K,Chanthavanich P, Suvannadabba S, et al. Protective efficacy of the recombinant, live-attenuated, CYD tetravalent dengue vaccine in Thai schoolchildren: a randomised, controlled phase 2b trial. The Lancet 2012;380(9853): 1559-1567.

[67] Villar L, Dayan GH, Arredondo-García JL, et al. Effi cacy of a tetravalent dengue vaccine in children in Latin America. The N Engl J Med 2015;372: 113-123.

[68] Dow G, Mora E. The maximum potential market for dengue drugs V 1.0. Antivir Res 2012; 96(2): 203-212.

[69] Faheem M, Raheel U, Riaz M, Kanwal N, Javed F, Zaidi Najam us Sahar Sadaf, et al. A molecular evaluation of dengue virus pathogenesis and its latest vaccine strategies. Mole Biol Rep 2011; 38(6): 3731-3740.

[70] Crill WD, Roehrig JT. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to domain III of dengue virus E glycoprotein are the most effi cient blockers of virus adsorption to Vero cells. J Virol 2001; 75(16): 7769-7773.

[71] Block OK, Rodrigo WW, Quinn M, Jin X, Rose RC, Schlesinger JJ. A tetravalent recombinant dengue domain III protein vaccine stimulates neutralizing and enhancing antibodies in mice. Vaccine 2010; 28(51): 8085-8094.

[72] Soares RO, Caliri A. Stereochemical features of the envelope protein domain III of dengue virus reveals putative antigenic site in the fi ve-fold symmetry axis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 2013; 1834(1): 221-230.

[73] Leng CH, Liu SJ, Tsai JP, Li YS, Chen MY, Liu HH, et al. A novel dengue vaccine candidate that induces cross-neutralizing antibodies and memory immunity. Microbes Infect 2009; 11(2): 288-295.

[74] Chiang CY, Liu SJ, Tsai JP, Li YS, Chen MY, Liu HH. A novel singledose dengue subunit vaccine induces memory immune responses. PLOS One[Online] 2011; 6(8): e23319. Available from doi: 10.1371/journal. pone.0023319.[Accessed 18th December 2014].

[75] Kim MY, Yang MS, Kim TG. Expression of a consensus dengue virus envelope protein domain III in transgenic callus of rice. Plant Cell, Tiss Org Culture 2012; 109: 509-515.

[76] Nguyen NL, Kim JM, Park JA, Park SM, Jang YS, Yang MS, et al. Expression and purifi cation of an immunogenic dengue virus epitope using a synthetic consensus sequence of envelope domain III and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expres Purif 2013; 88(2): 235-242.

[77] Chen HW, Liu SJ, Li YS, Liu HH, Tsai JP, Chiang CY, et al. A consensus envelope protein domain III can induce neutralizing antibody responses against serotype 2 of dengue virus in non-human primates. Arch Virol 2013; 158: 1523-1531.

[78] Carneiro AR, Cruz AC, Vallinoto M, Melo Diego de V, Ramos RJ,Medeiros DA, et al. Molecular characterisation of dengue virus type 1 reveals lineage replacement during circulation in Brazilian territory. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2012; 107(6): 805-812.

[79] Drumond BP, Mondini A, Schmidt DJ, de Morais Bronzoni, RV, Bosch I, Nogueira ML. Circulation of different lineages of dengue virus 2,genotype American/Asian in Brazil: Dynamics and molecular and phylogenetic characterization. PLOS One[Online] 2013; 8(3): e59422. Available from doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059422.[Accessed 20th December 2014].

[80] Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Siqueirra JB, et al. Cost of dengue cases in eight countries in the Americas and Asia: a prospective study. Am J Trop Med and Hyg 2009; 80(5): 846-855.

[81] Kanagaraj AP, Verma D, Daniell H. Expression of dengue-3 premembrane and envelope polyprotein in lettuce chloroplasts. Plant Mole Biol 2011; 76(3-5): 323-333.

ent heading

10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.03.004

15 January 2016

Hwei-San Loh (H.-S. Loh), Biotechnology Research Centre,The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Jalan Broga, 43500 Semenyih,Selangor, Malaysia.

Tel: +60389248215

Fax: +60389248018

E-mail: Sandy.Loh@nottingham.edu.my

in revised form 20 February 2016

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Determination of ligand cluster and binding site within VP40 of Ebola virus: clue for drug development

- Clinacanthus nutans: a review of the medicinal uses, pharmacology and phytochemistry

- Etiological agents causing leptospirosis in Sri Lanka: A review

- Phylogeny of Murray Valley encephalitis virus in Australia and Papua New Guinea

- Dengue outbreak in Swat and Mansehra, Pakistan 2013; an epidemiological and diagnostic perspective

- Bioactive extracts of red seaweeds Pterocladiella capillacea and Osmundaria obtusiloba (Floridophyceae: Rhodophyta) with antioxidant and bacterial agglutination potential