Antioxidant potential, tannin and polyphenol contents of seed and pericarp of three Coffea species

2016-11-14vaBrigittaPatayNikolettSaliTamszegiRitaCsepregiViktriaLillaBalzsTiborSebastianmethTibormethraPapp

Éva Brigitta Patay, Nikolett Sali, Tamás Kőszegi, Rita Csepregi, Viktória Lilla Balázs, Tibor Sebastian Németh, Tibor Németh, Nóra Papp*

1Institute of Pharmacognosy, Medical School, University of Pécs, Rókus 2, Pécs, Hungary, 7624

2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Ifjúság 13, Pécs, Hungary, 7624

3János Szentágothai Research Center, Ifjúság 20, Pécs, Hungary, 7624

4Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, University of Oradea, Piaţa 1 Decembrie u. 10, Oradea, Romania, 410073

Antioxidant potential, tannin and polyphenol contents of seed and pericarp of three Coffea species

Éva Brigitta Patay1, Nikolett Sali2,3, Tamás Kőszegi2,3, Rita Csepregi1, Viktória Lilla Balázs1, Tibor Sebastian Németh4, Tibor Németh4, Nóra Papp1*

1Institute of Pharmacognosy, Medical School, University of Pécs, Rókus 2, Pécs, Hungary, 7624

2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Ifjúság 13, Pécs, Hungary, 7624

3János Szentágothai Research Center, Ifjúság 20, Pécs, Hungary, 7624

4Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, University of Oradea, Piaţa 1 Decembrie u. 10, Oradea, Romania, 410073

Accepted 15 March 2016

Available online 20 April 2016

Coff ee

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

Enhanced chemiluminescence

Folin-Ciocalteau

Oxygen radical absorbance capacity

Total tannin method

Objective: To investigate the antioxidant activity, total phenolic and total tannin content of the pericarp and the seed of Coffea benghalensis (C. benghalensis) and Coffea liberica compared to Coffea arabica (C. arabica). Methods: The antioxidant potential, total tannin and polyphenol contents of the immature and mature seed and pericarp of C. benghalensis and Coffea liberica were quantified and compared to C. arabica. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), oxygen radical absorbance capacity, Folin-Ciocalteau method and total tannin content assays were used. Results: Trolox equivalent (TE/g plant material) values obtained by ECL and DPPH methods showed loose correlation (r2=0.587)while those measured by oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay were higher without correlation in each plant. A closer correlation was detected between the ECL method and the percentage antioxidant activity of the DPPH technique (r2=0.610 7) in each species, however the immature pericarp of C. benghalensis showed much higher DPPH scavenging potential than was seen in the ECL assay. The immature pericarp of C. benghalensis expressed the highest tannin and polyphenol content, and a high polyphenol level was also detected in the immature seed of C. arabica. The immature pericarp of Bengal and Liberian coff ees showed the largest amount of phenolic contents. Conclusions: The obtained data highlight the potential role of C. benghalensis as a new source of natural antioxidants and polyphenols compared to C. arabica.

1. Introduction

Coff ee (Coffea) species are evergreen shrubs or small trees which are native to the Ethiopian mountains[1,2]. They belong to the Rubiaceae family, which is the largest plant family in the world involving 450 genus and 6 500 species[3,4]. Nowadays, more than 120 Coffea species and their varieties are mentioned in scientifi c reports[5,6]. They grow in the tropical and subtropical areas,especially in the Equatorial region at an altitude of (200-1 200) m and between (18-22) ℃[7]. Coffea arabica (C. arabica) L., Coffea robusta (C. robusta) L. Linden, and Coffea liberica (C. liberica)Hiern have significant commercial value, occupying the second place after petrol on the international market[1,2]. Coff ee is one of the most widely consumed beverages worldwide, with an annual consumption rate of approximately 7 million tons according to FAO[8].

C. arabica (Arabic coffee) originated from Ethiopia is the most widespread coffee species. It provides 80% of the coffee production of the world[9]. The wild species Coffea benghalensis (C. benghalensis) Roxb. (Bengal coffee), which has been reclassified into the Psilanthus genus (Psilanthus benghalensis Roxb. Ex Schult.),is a small shrub in South and Southeast Asia. Although, Bengal coff ee is rarely used in the industry, the cafesterol and bengalensol content, as well as the antimicrobial and antioxidant eff ects of the fruit have been determined[10-12]. C. liberica (Liberian coff ee) is also native to Africa, and it provides 2% of the total coff ee production of the world. Despite its lower demand, the volatile extract of its immature beans possessed higher antioxidant capacity than that of C. arabica and C. robusta[13].

In oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species have been suggested to participate in the initiation and propagation of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular and inflammatory diseases, cancer, and diabetes[14]. Antioxidants which are found naturally in many foods and beverages provide health benefi ts in preventing heart disease and cancer by fi ghting against cellular damage caused by free radicals in the body[15]. Coff ee species are rich in biologically active substances and polyphenols such as chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, caff eic acid,sinapic acid, kaempherol, quercetin, nicotinic acid, trigonelline,quinolic acid, tannic acid, pyrogallic acid and caffeine which possess antioxidant, hepatoprotective, anti-bacterial, antiviral, antiinfl ammatory and hypolipidaemic eff ects[16-24]. These compounds play an important role against pathogens and abiotic stress such as changes in temperature, water content, exposure to UV light levels and defi ciency in mineral nutrients[25]. In coff ee species, chlorogenic acid content and its cis-isomers have been determined to be higher in the leaves than the seeds which prove the eff ect of UV radiation on the geometric isomerisation of chlorogenic acid in the leaves[26]. The local use of coff ee extracts could prevent various dermatological disorders, in addition, they also could have UV protection for skin. During a clinical study 30 patients having dermatological face problems were locally treated with coffee seed extract. In comparison with the standard creams with placebo eff ect, coff ee extract reduced wrinkles and pigmentation, as well as it improved the appearance of patients’ skin[27]. The silverskin of C. arabica and C. robusta have antioxidant activity[28], while the extract of the green seed has an anti-infl ammatory eff ect[29]. The regular consumption of coff ee reduce the kidney, liver, premenopausal breast and colon cancer[30].

Although more than 100 Coffea species are known nowadays, only a few taxa have been extensively analyzed at present. Based on the widely used enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), oxygen radical absorbance capacity(ORAC) assays, total phenolic, and tannin methods[31], the aim of this study was to investigate the antioxidant activity, total phenolic and total tannin content of the pericarp and seed of C. benghalensis and C. liberica compared to the thoroughly studied C. arabica. The analyses were carried out to fi nd new sources of natural antioxidants for nutraceuticals, and a new utilization of wasted residues of coff ee products.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Plant materials

The mature and immmature fruits of C. benghalensis, C. liberica,and C. arabica were collected in the Botanical Garden of the University of Pécs in the spring of 2014. The samples were air-dried at room temperature in the shade. Voucher specimens were deposited and labeled with unique codes at the Institute of Pharmacognosy,University of Pécs. For the antioxidant assays, samples were ground(0.25 g each) and extracted with 5 mL 50% ethanol (Merck). The extracts were shaken for 20 min (Edmund Bühler, Labortechnik-Materialtech, Johanno Otto GmbH), then fi ltered and stored at 4 ℃in the dark until analyses (less than 7 d).

2.2. Chemicals and reagents

All chemicals, used for antioxidant assays, were of analytical or spectroscopic grade purity and highly purifi ed water (<1 μS) was used in our experiments. Horseradish peroxidase (POD from Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA, Serva) in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, H2O2(Molar Chemicals) diluted with citric acid (Ph. Hg. Eur), 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), luminol, para-iodophenol, diphenyl-2,2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH stable free radical), fluorescein-Na2salt,2,2’-azobis (2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH, all from Sigma-Aldrich), methanol and ethanol (Reanal, Hungary) were used as received. In the ORAC assay 75 mM phosphate buff er of pH 7.4 was applied.

Chemicals used for Folin-Ciocalteau methodology and for measurement of total tannin were the followings: AlCl3(Alfa Aesar), acetone, 25% HCl, ethyl acetate, 5% methanol-acetic acid(Molar Chemicals), distilled water, solution of sodium carbonate(Lach-Ner), phosphor-molybdo-tungstic reagent (Sigma-Aldrich),holystone (Reanal), hide powder, hexamethylene tetramine, and pyrogallol (VWR).

2.3. DPPH assay

Four mg DPPH in 100 mL methanol (0.1 mmol/L) was prepared and kept in the fridge being stable for at least 1 wk. For absorbance measurements standard 96-well microplates (Sarstedt) were applied. Twenty μL Trolox/blank/sample and 180 μL DPPH solution were pipetted into the wells (using a multichannel pipette), mixed and the absorbance was read at 517 nm after 30 min incubation in the dark at 25 ℃[32-34].

2.4. ECL

We adapted and modifi ed the method of Muller et al[35] as follows.

Reagents: Before the analysis 15 μU/mL POD working solution was freshly prepared from 1.5 U/mL POD stock stored at -20 ℃ in phosphate buff ered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) by dilution with the BSA containing phosphate buff er and was kept on ice. A working reagent of 1 360 μM H2O2was also freshly diluted with 0.1% citric acid from 10 M concentrated stock solution and was also kept on ice, protected from light. During the whole period of measurements these reagents were stored in melting ice. Both working solutions were stable for at least several hours.

The chemiluminescence detection reagent was prepared separately by dissolving luminol and p-iodophenol in 0.2 M boric acid/NaOH buff er, pH 9.6 and was refrigerated at 4 ℃ in brown bottles with a shelf life of several weeks. Trolox was used as standard in both assays. Trolox at 1 mM concentration was dissolved freshly in 50% ethanol weekly and kept at 4 ℃. Depending on the assay, Trolox dilutions in the range of (0-100) μM were prepared on the day of the experiments with the same diluents that were applied for the samples.

ECL antioxidant method: The chemiluminescence reaction was performed in 96-well white optical plates (Perkin-Elmer). The enzyme working solution and the ECL reagent was premixed (200 μL POD+70 μL ECL reagent) and kept on ice. The wells were fi lled with 20 μL Trolox/blank/sample and 270 μL of POD-ECL reagent was pipetted into each well with an 8-channel micropipette. The reaction was initiated by automated injection of 20 μL ice-cold H2O2in citric acid (fi nal concentrations of the components in the wells: 0.97 μU/mL POD, 101.6 μM luminol, 406.4 μM p-iodophenol, 88 μM H2O2). The chemiluminescence signal was followed for 20 min.

2.5. ORAC assay

Four μM fl uorescein (FL) stock was prepared in 75 mM phosphate buffer of pH 7.4 (stable for 1 wk in the fridge). The working FL solution was made freshly diluting the stock with phosphate buff er at a 1: 99 ratio (40 nmol/L). AAPH was also prepared just before the measurements in the phosphate buff er (400 mM). Trolox standard was used as described above. Into each well of black optical plates(Perkin Elmer) 25 μL of blank/standard/sample and 150 μL of diluted FL were pipetted and the plates were preheated to 37 ℃for 20 min. The outer wells of the plates were filled with 200 μL phosphate buff er, and only the inner 6×10 matrix was used for the assay. The reaction was initiated by automated injection of 25 μL AAPH solution into each well and fluorescence intensities were immediately monitored for 80 min (490/520 nm) at 150 s intervals. The fi nal concentrations of the components in the wells were as follows: FL 30 nM, AAPH 50 mM, Trolox (0-33.3) μM[36,37].

2.6. Folin-Ciocalteau methodology

The total phenolic concentration of the pericarp and seed was measured using the Folin-Ciocalteu method in each plant. 0.5 g powdered samples were mixed with 1 mL of 0.5% hexamethylene tetramine, 20 mL acetone, 2 mL of 25% HCl, and holystone. The mixtures were stored on refl ow refrigerator for 30 min, and shaken with distilled water and ethyl acetate in shaking funnel. The extracts were used in two solutions, separately. The fi rst part of the extracts were mixed with 1 mL AlCl3and 5% (v/v) methanol-acetic acid for further measurement, while the second parts were mixed with 5%(v/v) methanol - acetic acid producing the standard solution. After 30 min incubation, the absorbance of both samples was measured at 425 nm (A). The total phenolic concentration was calculated with the following formula: (1.25×A)/m, where m = mass of the sample in grams. Each analysis was performed in duplicate following the procedure described in the 7th European Pharmacopoeia[38].

2.7. Total tannin content

Powdered immature and mature pericarp of 0.5 g and seed of the selected 3 species were mixed with 150 mL distilled water, and then heated on water-bath for 30 min at 70 ℃. The cooled extracts were transferred quantitatively to a 250 mL volumetric fl ask, then fi ltrated and used for the reactions.

2.7.1. Total polyphenols

The fi ltrate with 5.0 mL was diluted to 25.0 mL with distilled water. The solution with 2.0 mL was mixed with 1.0 mL of phosphormolybdo-tungstic reagent and 10.0 mL of distilled water, and then it was diluted to 25.0 mL with a 290 g/L solution of sodium carbonate. After 30 min, the absorbance was measured at 760 nm (A1) against distilled water.

2.7.2. Polyphenols not adsorbed by hide powder

The fi ltrate with 10.0 mL was mixed with 0.10 g of hide powder,and then shaken for 60 min. The fi ltrate with 5.0 mL was diluted to 25.0 mL with distilled water, then 2.0 mL of this solution was mixed with 1.0 mL of phosphor-molybdo-tungstic reagent and 10.0 mL of distilled water. Then the mixture was diluted to 25.0 mL with a 290 g/L solution of sodium carbonate. After 30 min, the absorbance was measured at 760 nm (A2) against distilled water.

2.7.3. Pyrogallol standard solution for polyphenol content

Pyrogallol with 50.0 mg was dissolved in distilled water and diluted to 100.0 mL with the same solvent. The solution with 5.0 mL was diluted to 100.0 mL with distilled water, and then 2.0 mL of this solution was mixed with 1.0 mL of phosphor-molybdo-tungstic reagent and 10.0 mL water. This mixture was diluted to 25.0 ml with a 290 g/L solution of sodium carbonate. After 30 min, the absorbance was measured at 760 nm (A3) against distilled water. Each analysis was performed in duplicate. Polyphenol contents were calculated with the following formulas[38]:

Polyphenols not adsorbed by hide powder: [62.5×(A1-A2)×m2]/A3×m1

m1= mass of the sample to be examined in grams

m2= mass of pyrogallol in grams

Total polyphenols: [62.5×A1×m2]/A3×m1

m1= mass of the sample to be examined in grams

m2= mass of pyrogallol in grams

Table 1Total antioxidant capacity of Coffea species measured by three diff erent spectroscopic methods (mean± SD).

2.8. Instrumentation and interpretation of data

For the ECL based measurements a Biotek Synergy HT plate reader equipped with programmable injectors was used. After initiation of the reaction by injection of H2O2, light detection was immediately begun with 0.2 s measuring time/well for 20 min at 64 s measuring intervals. Trolox standards in 50% ethanol were applied in the range of (0-15) μM fi nal concentrations in the wells and a 32-fold dilution with 50% ethanol of the plant extracts were used for the measurements (n = 12 replicates for each sample). The total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of the extracts was calculated from the regression equation obtained for the standards, multiplied by the dilution factor and expressed as μM Trolox equivalent (TE). TE for each plant extract was referred to 1 g of initial dry material.

For the DPPH assay a Perkin Elmer EnSpire Multimode reader was used in absorbance mode, equipped with monochromators. Standardization of the assay was done by application of (0-25) μM Trolox/well final concentrations in 50% ethanol and absorbance values were read at 517 nm after 30 min of incubation at 25 ℃ (with 5 s shaking before the measurement). Antioxidant capacities were calculated either by using the equation of the calibration line or by expressing the antioxidant activity of the extracts in % of the blank using the formula: (Ablank- Asample/Ablank)×100[39]. TAC values were also referred to 1 g of dried plant and were given as TE/g or % TAC/g. For the ORAC assay the Biotek Synergy HT plate reader was used in fl uorescence mode at 37 ℃ with 490 nm excitation and 520 nm emission filter settings. After 20 min incubation of the plate containing blanks/standards/samples and FL at 37 ℃ the AAPH start reagent was automatically injected into the wells and readings were taken in every 150 s for 80 min with 100 intensity readings/ well at each measuring point. TE was calculated by subtraction of the fl uorescence intensities of the corresponding blank values from those of the Trolox standards (net area under curve) and in this way a calibration line was obtained based on net area under curve vs. Trolox concentrations. TE data for the examined plants were obtained from the regression equation of the standards and were also referred to 1 g of dry plant.

3. Results

3.1. Antioxidant activity tests (DPPH, ECL and ORAC)

We could quantify the antioxidant activity by both three methods of all tested plant extracts. The ECL and DPPH TE/g values showed loose correlation (r2=0.587, P=0.083 by Student’s t-probe) while those obtained for the ORAC assay were considerably higher with a more uniform pattern and without correlation with the other two assays’ data (Table 1).

The imprecision of the three assays was acceptable (ECL:≤5%,DPPH: ≤10%, ORAC: ≤2%). The DPPH data were also calculatedas % TAC using the equation described in 2.8. Our results showed closer correlation between the ECL method and the percentage antioxidant capacity obtained by the DPPH technique (r2=0.610 7,P=0.161 by Student’s t-probe). The biggest difference was seen for the immature pericarp of C. benghalensis and for the mature pericarp of C. liberica where the DPPH method showed much higher antioxidant capacity than the ECL assay (Figure 1 and Figure 2). In our experiments, the ORAC technique showed the highest values which did not correlate with the results of the other two assays. In contrast to the data of Kiran, Baruah, Ojha, Lalitha & Raveesha, 2011 the antioxidant activity of mature fruit extracts of C. benghalensis (DPPH method) we found lower than theirs however,that of immature pericarp was higher in our study.

Although C. liberica is less used commercially, the antioxidant eff ect of its green seeds is comparable to that of C. arabica and C. robusta[40].

The ORAC and the ECL assays belong to the hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) mechanism group while the DPPH technique is considered to be based on single electron transfer[41]. Both techniques are considered to characterize the non-enzymatic total antioxidant capacity of the plant extracts. The ECL method applying phenolic compound as enhancer proved to be more sensitive than the ORAC assay however, the measuring range and precision of the ORAC method were more favorable. In the ECL technique the phenolic enhancer compound itself is also involved in the reaction with POD intermediates accelerating the reaction by increasing the turnover rate of the enzyme. Apart from POD-phenolic interaction the resulting phenoxyl radicals can directly oxidize luminal[42]. It is uncertain yet why the TE/g values obtained by the ORAC HAT assay were considerably higher than those seen for the other two methods. It might be postulated that in the ORAC microenvironment more antioxidant compounds could react with the AAPH oxidant than in the DPPH (single electron transfer) and ECL (HAT) type assays. In order to explain the diff erences between the various methods we plan to separate active compound of the Coffea species and measure their antioxidant capacity separately by both techniques.

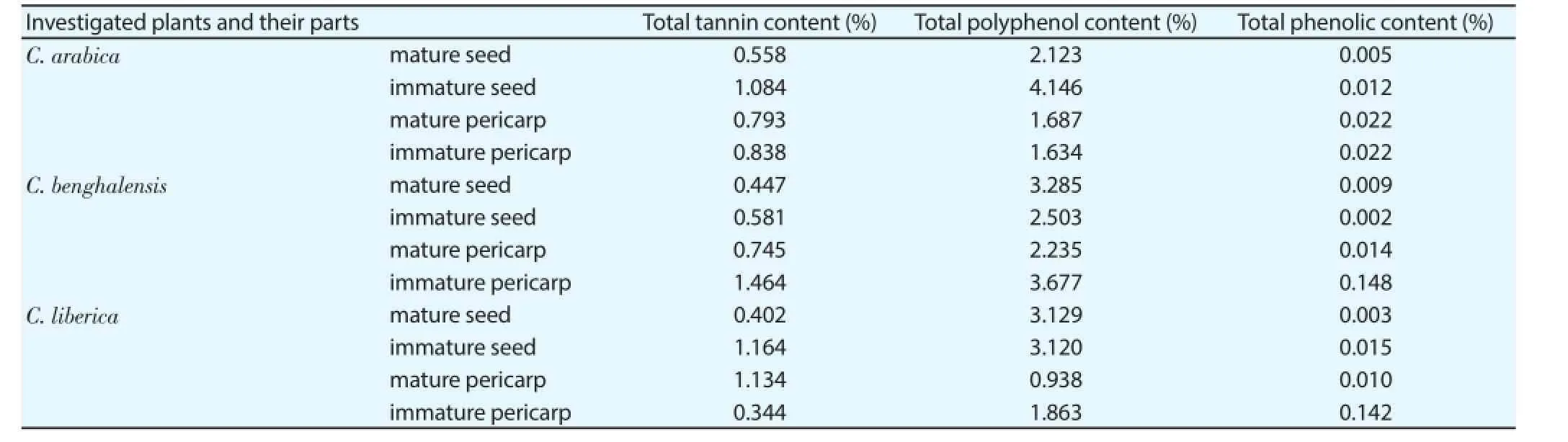

Table 2Total tannin, polyphenol and phenolic content of Coffea species measured by diff erent spectroscopic methods.

Figure 1. Scavenger activity of the studied Coffea species measured by DPPH method.

Figure 2. Comparison of the ECL assay with the DPPH method.Data obtained from the coff ee plant extracts are expressed in TE/g dried plant(ECL method) and in TAC % (DPPH method).

3.2. Folin-Ciocalteau method and total tannin content

Total tannin and polyphenol content of the selected Coffea species were measured by diff erent spectroscopic methods (Table 2). The highest tannin content was found in the immature pericarp of Bengal coff ee followed by the immature seed of Liberian and Arabic coff ee. The least tannin content was detected in the mature seed extract of each species. The highest polyphenol content was measured in the immature seed of C. arabica and in the immature pericarp of C. benghalensis while the least content was observed in the mature pericarp of C. liberica. In addition, a high polyphenol concentration value was detected in the mature seed of all three species. High phenolic content was measured in the immature pericarp extracts of C. benghalensis and C. liberica. The other plant extracts contained low phenolic concentrations.

In comparison with other studies the antioxidant activity and total polyphenol content of green coffee extracts of C. arabica were higher, when the extraction was made with isopropanol and water(60: 40), than seen in our study. These diff erences could be explained by the diff erent extraction methods used[20].

4. Discussion

Among the used antioxidant assays, the measured ECL and DPPH values indicated a loose correlation in contrast with the data of the ORAC assay, while a closer correlation was observed between the ECL technique and the expressed antioxidant potential studied by the DPPH method in each coff ee species. The much higher antioxidant activities measured by the ORAC assay might refl ect the diff erences in the reactive antioxidant compounds among the assays and/or the altered reactivity with the reporter molecules. The immature pericarp of Bengal and Liberian coff ee produced a high phenolic content, and in comparison, the immature pericarp of Bengal coff ee showed the most signifi cant tannin and polyphenol content similarly to the high polyphenol content of the immature seed of Arabic coff ee. These data highlight the potential role of Bengal coff ee as a new source for natural antioxidants and polyphenols compared to the Arabic coff ee.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there was no confl ict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The present scientific contribution is dedicated to the 650th anniversary of the foundation of the University of Pécs, Hungary. We are grateful for the plant samples for the Botanical Garden of the University of Pécs. This work was supported by Domus (Domus Szülőföldi Junior Ösztöndíj 2014; Domus Magyarországi Junior Ösztöndíj 2015) and PTE ÁOK-KA-2013/15 grants.

[1] Davis AP, Chester M, Maurin O, Fay MF. Searching for the relatives of Coffea (Rubiaceae, Ixoroidae): The circumscription and phylogeny of Coff eae based on plastid sequence data and morphology. Am J Bot 2007;94(3): 313-329.

[2] Patui S, Clincon L, Peresson C, Zancani M, Conte L, Terra DL, et al. Lipase activity and antioxidant capacity in coffee (Coffea arabica L.)seeds during germination. Plant Sci 2014; 219-220: 19-25.

[3] Borhidi A. A zárvatermők rendszertana molekuláris filogenetikai megközelítésben. Pécs: Pécsi Tudományegyetem Biológiai Intézet; 2008,p. 12-14, 111-113, 208, 226-228.

[4] Wiart C. Ethnopharmacology of medicinal plants. Asia and the Pacific. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 2006, p. 167-168.

[5] Davis AP, Tosh J, Ruch N, Fay MF. Growing coffee: Psilanthus(Rubiaceae) subsumed on the basis of molecular and morphological data; implications for the size, morphology, distribution and evolutionary history of Coff ea. Bot J Linn Soc 2011; 167(4): 357-377.

[6] Judd WS, Campbell CS, Kellog EA, Stevens PF. Plant systematics. Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates; 1999, p. 365-366.

[7] Rohwer JG. A trópusok növényei. Budapest: Magyar Könyvklub; 2002, p. 148.

[8] Baeza G, Benavent MA, Sarriá B, Goya L, Mateos R, Bravo L. Green coff ee hydroxycinnamic acids but not caff eine protect human HepG2cells against oxidative stress. Food Res Int 2014; 62: 1038-1046.

[9] Gonzalez IS, Escrig AJ, Calixto FS. In vitro antioxidant activity of coff ees brewed using different procedures (Italian, espresso and filter). Food Chem 2005; 90(1-2): 133-139.

[10] Kiran B, Baruah R, Ojha R, Lalitha V, Raveesha KA. Antibacterial and antioxidant activity of Coffea benghalensis Roxb. Ex. Schult. Fruit against human bacteria. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci 2011; 2(3): 856-865.

[11] Nowak B, Schulz B. A trópusok gyümölcsei. Budapest: Magyar Könyvklub; 2002, p. 165-166.

[12] Bilkis B, Choudhury MH, Mohammad AR. Caffeine from the mature leaves of Coffea bengalensis. Biochem Syst Ecol 2003; 31(10): 1219-1220.

[13] Chee AKS, Yam WS, Wong KC, Lai CS. A comparative study of the volatile constituents of southeast Asian Coffea arabica, Coffea liberica and Coffea robusta green beans and their antioxidant activities. TEOP 2015;18(1): 64-73.

[14] Durak A, Dziki UG, Pecio L. Coffee with cinnamon-impact of phytochemicals interactions on antioxidant and anti-infl ammatory in vitro activity. Food Chem 2014; 162: 81-88.

[15] Ramalakshmi K, Kubra IR, Rao LJM. Antioxidant potential of low-grade coff ee beans. Food Res Inter 2008; 41(1): 96-103.

[16] Mussatto SI, Ballesteros LF, Martins S, Teixeira JA. Extraction of antioxidant phenolic compounds from spent coff ee grounds. Sep Purif Technol 2011; 83: 173-179.

[17] Huang MT, Smart RC, Wong CQ, Conney AH. Inhibitory effect of curcumin, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid on tumor promotion in mouse skin by 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Cancer Res 1988; 48(21): 5941-5946.

[18] Narayana KR, Reddy MS, Chaluvadi MR, Krishna DR. Bioflavonoids classification, pharmacological, biochemical effects and therapeutic potential. Indian J Pharmacol 2001; 33(1): 2-16.

[19] Yeh CT, Yen GC. Effects of phenolic acids on human phenolsulfotransferases in relation to their antioxidant activity. J Agr Food Chem 2003; 51(5): 1474-1479.

[20] Naidu MM, Sulochanamma G, Sampathu SR, Srinivas P. Studies on extraction and antioxidant potential of green coff ee. Food Chem 2008;107(1): 377-384.

[21] Brezova V, Šlebodova A, Staško A. Coff ee as a source of antioxidants: An EPR study. Food Chem 2009; 114(3): 859-868.

[22] Dziki UG, Świeca M, Dziki D, Kowalska I, Pecio L, Durak A, et al. Lipoxygenase inhibitors and antioxidants fromgreen coff ee-mechanism of action in the light of potential bioaccessibility. Food Res Int 2014; 61: 48-55.

[23] Gîrd CE, Nencu I, Costea T, Duţu LE, Popescu ML, Ciupitu N. Quantitative analysis of phenolic Compounds from Salvia officinalis L. leaves. Farmacia 2014; 62(4): 649-657.

[24] Quiroz MLS, Campos AA, Alfaro GV, Rios OG, Villeneuve P, Espinoza MCF. Isolation of green coff ee chlorogenic acids using activated carbon. J Food Compos Anal 2014; 33(1): 55-58.

[25] Monteiro MC, Farah A. Chlorogenic acids in Brazilian Coffea arabica cultivars from various consecutive crops. Food Chem 2012; 134(1): 611-614.

[26] Clifford MN, Kirkpatrick J, Kuhnert N, Roozendaal H, Salgado PR. LCMSn analysis of the cis isomers of chlorogenic acids. Food Chem 2008;106(1): 379-385.

[27] Cooper R, Kronenberg F. Botanical medicine. New Rochelle: Mary Ann Liebert; 2009, p. 51.

[28] Narita Y, Inouye K. High antioxidant activity of coff ee silverskin extracts obtained by the treatment of coff ee silverskin with subcritical water. Food Chem 2012; 135(3): 943-949.

[29] Ross IA. Medicinal plants of the world. Volume 3. New Jersey: Humana Press Inc; 2005, p. 155-184.

[30] Nkondjock A. Coff ee consumption and the risk of cancer: An overview. Cancer Lett 2009; 277(2): 121-125.

[31] Vignoli JA, Bassoli DG, Benassi MT. Antioxidant activity, polyphenols,caff eine and melanoidins in soluble coff ee: The infl uence of processing conditions and raw material. Food Chem 2011; 124(3): 863-868.

[32] Jiménez YC, Moreno GMV, Igartuburu JM, Barosso CG. Simplification of the DPPH assay for estimating the antioxidant activity of wine and wine by-products. Food Chem 2014; 165: 198-204.

[33] Chen Z, Bertin R, Froldi G. EC50estimation of antioxidant activity in DPPH assay using several statistical programs. Food Chem 2013; 138(1): 414-420.

[34] Sharma OP, Bhat TK. DPPH antioxidant assay revisited. Food Chem 2013; 113(4): 1202-1205.

[35] Muller CH, Lee TKY, Montaño MA. Improved chemiluminescence assay for measuring antioxidant capacity of seminal plasma. Methods Mol Biol 2013; 927: 363-376.

[36] Gillespie KM, Chae JM, Ainsworth EA. Rapid measurement of total antioxidant capacityin plants. Nat Protoc 2007; 2(4): 4867-4870.

[37] Dávalos A, Cordovés CG, Bartalomé B. Extending applicability of the oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC-Fluorescein) assay. J Agr Food Chem 2004; 52(1): 48-54.

[38] Council of Europe: European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare. European Pharmacopoeia, 7th ed. Strasbourg; 2010.

[39] Lu Y, Shipton FN, Khoo TJ, Wiart C. Antioxidant activity determination of citronellal and crude extracts of Cymbopogon citratus by 3 diff erent methods. Pharmacol Pharm 2014; 5(4): 395-400.

[40] Teo HM, Yam WS, Lai CS. Antioxidative activities of Coffea liberica green beans and its phytochemical constituents. Pharmacol Pharm Sci 2014; 1(12): 176.

[41] Prior RL, Wu X, Schaich K. Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. J Agr Food Chem 2005; 53: 4290-4302.

[42] Easton PM, Simmonds AC, Rakishev A, Egorov AAM, Candeias LP. Quantitative model of the enhancement of peroxidase-induced luminol luminescence. J Am Chem Soc 1996; 118(28): 6619-6624.

ent heading

10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.03.014

15 January 2016

Nóra Papp, Institute of Pharmacognosy, Medical School,University of Pécs, Rókus 2 Pécs, Hungary, 7624

Tel: +36 72503650 (ext. 28824)

E-mail: nora4595@gamma.ttk.pte.hu

Foundation project: This work was supported by Domus (Domus Szülőföldi Junior Ösztöndíj 2014; Domus Magyarországi Junior Ösztöndíj 2015) and PTE ÁOK-KA-2013/15 grants.

in revised form 20 February 2016

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Determination of ligand cluster and binding site within VP40 of Ebola virus: clue for drug development

- Clinacanthus nutans: a review of the medicinal uses, pharmacology and phytochemistry

- Current perspectives on dengue episode in Malaysia

- Etiological agents causing leptospirosis in Sri Lanka: A review

- Phylogeny of Murray Valley encephalitis virus in Australia and Papua New Guinea

- Dengue outbreak in Swat and Mansehra, Pakistan 2013; an epidemiological and diagnostic perspective