Fruits extracts of Hovenia dulcis Thunb. suppresses lipopolysaccharidestimulated inflammatory responses through nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in Raw 264.7 cells

2016-11-14JuYeonParkJinYoungMoonSunDongParkWonHwanParkHyuckKimJaiEunKim

Ju-Yeon Park, Jin-Young Moon, Sun-Dong Park, Won-Hwan Park, Hyuck Kim*, Jai-Eun Kim

1Department of Acupoint, College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Siksa-dong, Ilsan, Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do 10326, Republic of Korea

2Department of Prescription, College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Siksa-dong, Ilsan, Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do 10326, Republic of Korea

3Department of Diagnostics, College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Siksa-dong, Ilsan, Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do 10326, Republic of Korea

4Department of Pathology, College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Siksa-dong, Ilsan, Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do 10326, Republic of Korea

Fruits extracts of Hovenia dulcis Thunb. suppresses lipopolysaccharidestimulated inflammatory responses through nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in Raw 264.7 cells

Ju-Yeon Park1, Jin-Young Moon1, Sun-Dong Park2, Won-Hwan Park3, Hyuck Kim3*, Jai-Eun Kim4*

1Department of Acupoint, College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Siksa-dong, Ilsan, Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do 10326, Republic of Korea

2Department of Prescription, College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Siksa-dong, Ilsan, Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do 10326, Republic of Korea

3Department of Diagnostics, College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Siksa-dong, Ilsan, Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do 10326, Republic of Korea

4Department of Pathology, College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Siksa-dong, Ilsan, Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do 10326, Republic of Korea

Accepted 15 March 2016

Available online 20 April 2016

Fruits of Hovenia dulcis

Infl ammation

Macrophage

Nuclear factor-kappaB Heme oxygenase-1

Objective: To investigate the anti-infl ammatory eff ects and the action mechanism of the fruits of Hovenia dulcis (H. dulcis) in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced mouse macrophage Raw 264.7 cells. Methods: The extract of H. dulcis fruits (EHDF) were extracted with 70% ethanol. Mouse macrophages were treated with diff erent concentrations of EHDF in the presence and absence of LPS (1 μg/mL). To demonstrate the infl ammatory mediators including nitric oxide, inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 expression levels were analyzed by using in vitro assay systems. COX-derived pro-infl ammatory cytokines including interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α and prostaglandin E2were determined using ELISA kits. Cell viability, heme oxygenase-1 expression,nuclear factor-kappaB and nuclear factor E2-related factors 2 translocation were also investigated.

Results: EHDF potently inhibited the LPS-stimulated nitric oxide, inducible nitric oxide synthase,COX-2, interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α expression in a dose-dependent manner. EHDF suppressed the phosphorylation of inhibited kappaB-alpha and p65 nuclear translocation. Treatment of macrophage cells with EHDF alone induced the heme oxygenase-1 and nuclear translocation of nuclear factor E2-related factor 2. Conclusions: These results suggest that the ethanol extract of H. dulcis fruit exerts its anti-infl ammatory eff ects by inhibiting inhibited kappaB-alpha phorylation and nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-kappaB.

1. Introduction

Infl ammation is the fi rst response of body immune system which is triggered by exogenous pathogens, external stimuli such as harmful chemicals and bacterial infection[1]. The inflammatory processes which are characterized by leukocyte recruitment and macrophages are considered to play a critical role in the initiation and development of inflammation[2-5]. In the presence of an endotoxin such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), activated macrophages produce numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis-α(TNF-α), interleukin-1β(IL-1β) and interleukin-10, as well as macrophage-derived infl ammatory mediators such as nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin E2(PGE2)[6,7]. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression is involved during the NO production during infl ammation and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)enzyme is considered to be responsible for the expression of PGE2in infl ammatory progress[8].

Nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB), a protein complex, is one of the most ubiquitous transcription factors. The phosphorylation of NF-κ B plays a key role in regulating the infl ammatory responses[9]. NF-κB is constitutively localized in the cytoplasm as a homodimer or heterodimer in normal cells, which is activated by a family of inhibitory factors called inhibitory-factor kappaB (IκB)[10]. When cells are under infl ammatory condition, NF-κB is activated and subsequently translocated into the nucleus, followed by amplification of the infl ammatory response by overexpression of several infl ammation related genes including iNOS, COX-2 and TNF-α[11,12].

Oxidative stress is potently associated with the process of infl ammation not only through injurious eff ects, but also by the host defense against invading microbes[13]. There are many enzymatic anti-oxidants and anti-infl ammatory systems in the host defense including phase Ⅱ detoxifying enzymes and the expression of stress response proteins such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)[14,15]. HO-1,which belongs to the heat shock protein family, is catalyzed by the oxidation of heme to the biologically active products such as carbon monoxide, biliverdin, and ferrous iron (Fe2+)[16,17]. Hence, HO-1 is considered to contribute in diverse immune responses through antioxidation and anti-infl ammation activities in the human body[18]. Nuclear factor E2-related factors 2 (Nrf2), as well known HO-1 promotor, is a basic leucine zipper transcription factor that regulates phase Ⅱ enzyme by induction of detoxifying genes through antioxidant response elements[19]. An increasing number of reports have also suggested that Nrf2 play a predominant role by interacting with cognate DNA-binding domains[20,21].

Hovenia dulcis (H. dulcis) Thunb. (Rhamanaceae), mainly found in China, Japan and Korea, has been widely used as a valuable crude drug to treat various diseases such as hepatitis and diabetes[22]. Recently, several studies indicated that the H. dulcis extract contains an extensive of pharmacological compounds, such as alkaloids,fl avonoids, and triterpenoids[23]. However, the precise mechanisms responsible for the suppression of LPS-stimulated inflammatory response by the ethanol extract of H. dulcis fruits (EHDF) remains unclear. This study demonstrated the bio-pharmacological mechanisms of EHDF, and functions for these anti-inflammatory eff ects. Furthermore, the study investigated that EHDF have antiinfl ammatory eff ects in LPS-induced Raw 264.7 macrophage cells through the Nrf2-dependent HO-1 induction. In addition, EHDF strongly inhibited LPS-induced NO production via the direct downregulation of iNOS, and the study also showed the Nrf-dependent HO-1 up-regulation. These results suggest that EHDF is a potential Nrf-dependent HO-1 regulator for anti-infl ammatory activities.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) and fetal bovine serum from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, MD). ELISA kits were purchased from R&D Systems Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Tin protoporphyrin Ⅸ(SnPP) was from Porphyrin Products (Logan, UT, USA). Primary antibodies, including anti-HO-1, anti-COX-2, anti-iNOS, anti-IκB, anti-p-IκB, anti-NF-κB (p65), anti-Nrf2 and secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA,USA). DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2phenylindole) was from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Other chemicals for this study were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA)unless indicated otherwise.

2.2. Plant material and preparation of ethanol extracts

The fruits of H. dulcis Thunb. (Rhamnaceae) were purchased from Daehak Hanyakguk, Iksan, Korea in 2014. A voucher specimen (no. 14-MRC-220AP) was authenticated by Dr. Sun-Dong Park, college of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University (Korea). The specimens were deposited at the College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University. Dried fruits of H. dulcis (50 g) was extracted with 70% ethanol (300 mL) at Soxhlet extraction for 3 h, and the extract was concentrated in vacuo to obtain a 70% ethanol extract (2.31 g). Ethanol extract was suspended in H2O and centrifuged at 2 500 rpm for 30 min. Precipitate was dissolved in ethanol, and evaporated in vacuo to obtain an extraction (696 mg). For each experiment, EHDF was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxiede (fi nal culture concentration,0.05%). Preliminary studies indicated that the solvent had no eff ect on the cell viability at the concentration used.

2.3. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Chromatographic experiments were performed on YL-9100 series HPLC instrument equipped with a sample injector and a photodiode array UV/Vis detector (PDA) (YoungLin, Korea). For all experiments, an SHISEIDO CAPCELL PAK C-18 column (4.6 nm×250 nm, 5 μm, SHISEIDO CO., Tokyo, Japan) was used as the stationary phase, and the injection volume was 20 μL. The mobile phase was composed of water (contain 0.1% formic acid) and methanol, with an applied gradient of 10% B increasing to 100% B in 40 min. The column was cleaned with 100% B for 10 min. Flow rate was 0.7 mL/min, and the detection wavelength was adjusted to 254 nm.

2.4. Cell culture and viability assay

RAW 264.7 macrophages were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modifi ed Eagle’s Medium, supplemented with 10% heatinactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and maintained in a humidifi ed incubator at 37 ℃, 5% CO2. To assess the cell viability caused by EHDF, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used. The cells were suspended in 96 well plates at 4×105cells/mL, and treated with varying EHDF. After pre-treatment of EHDF, cells were incubated for 24 h, and the supernatant was removed. Ten μL of MTT solution(5 mg/mL) in 90 μL of serum-free medium was treated for additional 4 h. The formazan was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxiede, and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm.

2.5. Nitrite assay

The cells were pre-treated with EHDF for 30 min, with or without LPS (1 μg/mL). 100 μL of each supernatant from EHDF treated well were responded with an equal volume of the Griess reagent [1% sulfanilamide/0.1% N-(1-naphthyl)-ethyle-nediamine dihydrochloride/2.5% H3PO4] at room temperature for 10 min. The nitrite concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 540 nm with a microplate reader, and calculated using a standard curve of sodium nitrite.

2.6. TNF-α, IL-1β and PGE2ELISA assay

RAW 264.7 cells were pre-incubated with various concentrations of EHDF for 12 h, and then stimulated for 18 h with LPS. The supernatants of each well were harvested, and contents of cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β and PGE2were evaluated using ELISA kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems).

2.7. Preparation of nuclear and cytosolic fractions

The cells treated with or without EHDF were harvested and washed with PBS. The pellets were resuspended using NE-PER™ nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (Thermo Scientific, IL, USA)according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefl y, the cytosolic fraction of cells were prepared by centrifugation at 15 000 g for 5 min at 4 ℃, and the supernatant was transferred to a clean tube. Subsequently, the nuclear fractions were prepared by centrifugation at 15 000 g for 10 min at 4 ℃. The nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were then stored at -80 ℃, until further use. The amounts of proteins in each extract were quantifi ed using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Thermo Scientifi c).

2.8. Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3 000 g for 5 min, and the cell pellet was collected and washed twice with ice-cold PBS. The cell pellet was dissolved in PRO-PREP™ Protein Extraction Solution (iNtRON Biotechnology, Inc.), and the concentrations of proteins were measured by bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit(Pierce). The cell lysates were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel elctrophoresis with an equal volume,and then transferred onto polyvinylidene fl uoride membrane. After blocking at room temperature for 1 h, with 5% skimmed milk powder in Tris-Buffered Saline Tween-20 (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20), the blots were incubated with iNOS, COX-2, Nrf2, NF-κB (p65), lamin B, β-actin,phospho-IκB-α, IκB-α, HO-1 polyclonal antibodies at 4 ℃ for overnight. After incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase at room temperature for 1h, the bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Bioscience, Buckinghamshire, UK). The intensity of the bands was quantified with Fusion FX7 chemiluminescence imaging system(Vilber Lourmat, Marne-la-vallée, France).

2.9. Immunofluorescence microscopy

For localization of NF-κB and Nrf2, Raw264.7 macrophages were grown on Lab-Tek Ⅱ chamber slides (Nunc, Thermo Scientifi c). The day after plating macrophages on coverslips with or without of EHDF at a diff erent concentrations in the presence and absence of LPS (1 μg/mL), the cells were fixed in methanol for 10 min at -20 ℃. The cells were then permeablized in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Nrf2 antibody followed by fl uorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). And the coverslips were mounted on glass slides using Dako Fluorescent mounting medium. And observed using a Zeiss fl uorescence microscope (ProvisAX70, Olympus Optical Co.,Tokyo, Japan)

2.10. Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean±sd. Experimental data were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism version 5.0 software. The signifi cance was assessed with a one-way ANOVA test with tukey’s multiple comparison, and P<0.05 was considered signifi cant. Each experiment was performed at least 3 times using samples from diff erent preparations.

3. Result

3.1. HPLC analysis of EHDF

Data from the HPLC analysis of EHDF were recorded in the form of chromatograms by monitoring detector responses at 254 nm. As shown in Figure 1, the results indicated that two bioactive components of H. dulcis observed were kaempferol and quercetin,which were mainly detected upon UV absorption.

Figure 1. HPLC chromatogram of EHDF.

3.2. Effect of EHDF on cell viability in Raw264.7 macrophage

MTT assay was used to first investigate the effect of EHDF on cell viability. As shown in Figure 2, exposures to the EHDF at five different concentrations for 24 h caused little effect on the macrophages. This result clearly revealed that the EHDF at the highest test concentration (120 μg/mL) produced 25% reduction of cell viability, whereas the extract at the lower concentrations had no eff ects on the cell viability, proving that EHDF was safe for the mouse macrophage Raw 264.7 cells. For all further experiments, the macrophages were treated with EHDF in the range of 5-100 μg/mL.

Figure 2. Eff ects of EHDF on cell viability.

3.3. Effect of EHDF on iNOS and COX-2 expression in Raw 264.7 macrophage

As shown Figure 3A, LPS stimulation signifi cantly increased the iNOS expression. However, pretreatment with the EHDF up to 100 μg/mL had potently reduced the protein expressions of iNOS in a dose-dependent manner. Next, study found that pretreated with noncytotoxic concentrations (5-100 μg/mL) of EHDF for 1 h strongly reduced the COX-2 enzyme levels on LPS-stimulated macrophage cells in a dose-dependently manner (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Eff ects of EHDF on LPS-induced expression of iNOS and COX-2 protein in Raw264.7 macrophages.A: Change in protein levels of iNOS; B: Change in protein levels of COX-2. Compared with LPS-treated group,###P<0.005. Compared with control group,**P<0.01,***P<0.005.

3.4. Effect of EHDF on LPS-induced production of NO and pro-inflammatory cytokines

Pretreatment of cells with 5 and 100 μg/mL of EHDF dramatically reduced the NO production in LPS-stimulated Raw 264.7 cells (Figure 4A). As shown in Figure 4B, the pre-treatment of macrophages with EHDF for 18 h results in the inhibition of IL-1 β production. Under the same conditions, EHDF also caused a decrease in TNF-α production in macrophage cells (Figure 4C). In addition, PGE2level in the supernatants were determined by ELISA. As shown in Figure 4D, EHDF a signifi cant reduction of PGE2level was observed in the medium.

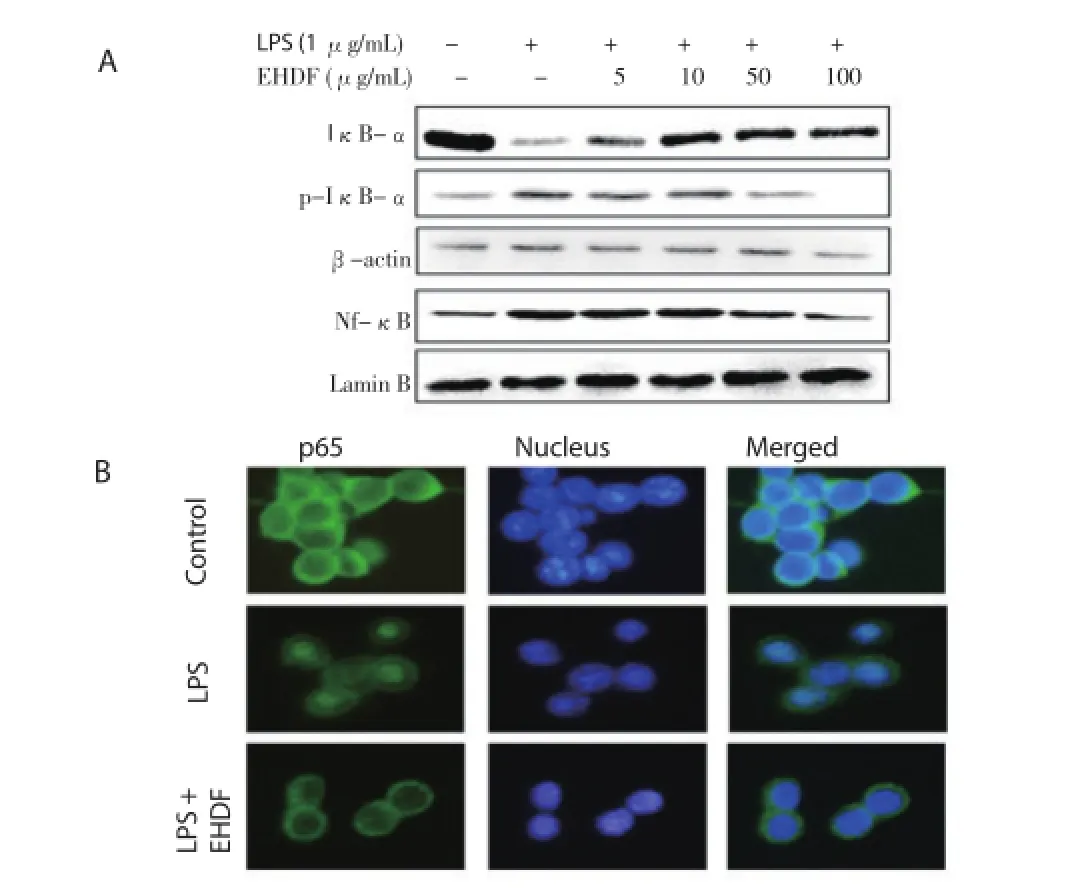

3.5. Effect of the EHDF on LPS-induced NF-κB nuclear translocation and IκB phosphorylation

As shown in Figure 5A, IκB-αα was degraded after treatment with LPS at 1 μg/mL for 1 h, and this degradation was markedly reduced by pre-treatment of the macrophage cells with various concentrations of EHDF ranging from 5 to 100 μg/mL for 18 h. On the other hand, pretreatment of the EHDF reduced the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and phosphorylation of IκB in the cytoplasm. In addition, Figure 5B shown that LPS alone signifi cantly increased the translocation of NF-κB p65 subunits to the nucleus in the cytoplasm. However, pre-treatment of macrophages with 100 μg/ mL of EHDF for 18 h results in the reduction of p65 translocation.

Figure 5. Effects of EHDF on LPS-induced activation of NF-κB nuclear translocation and IκB phosphorylation.A: Western blot analysis of p65 subunit of NF-κB in nuclear fractions of Raw 264.7 cells treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of different concentrations of EHDF; B: Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis.

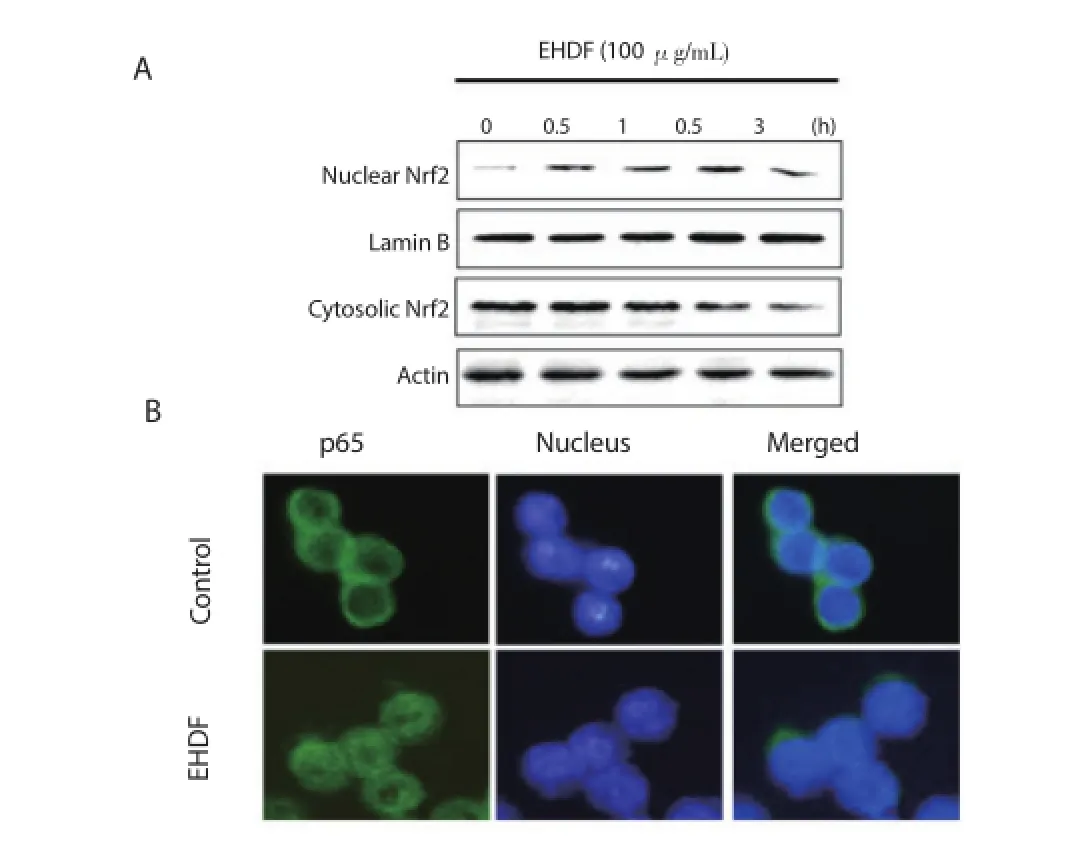

3.5. Effects of EHDF onHO-1 expression and nuclear translocation of Nrf2

As shown in figure 6A, in cells treated for 18 h with various concentrations of EHDF ranging from 5-100 μg/mL, we found a concentration-dependent increase of HO-1 protein expression. We also determined a time course-dependent HO-1 induction was determined in the protein expressions level (Figure 6B). Nrf2 is a well-known HO-1 regulator and coordinates the induction of phaseⅡ enzyme genes. Therefore, we investigated whether treating macrophage cells with EHDF induced nuclear translocation of Nrf2. As shown in Figure 7A, at 100 μg/mL of EHDF, the nuclear fractions of time course-treated macrophage cells showed a gradual increase in Nrf2 levels at 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 3.0 h. In addition, for localization of Nrf2, similar results were also observed using immunofl uorescence microscopy (Figure 7B).

Figure 6. Eff ects of EHDF on HO-1 expression in Raw264.7 macrophages. A: Macrophages were incubated for 18 h with diff erent concentrations of EHDF; B: Macrophages were incubated for indicated periods with 100 μg/ mL of EHDF. Compared with control group,***P<0.005.

Figure 7. Eff ects of EHDF on nuclear translocation of Nrf2.A: Macrophages were incubated for indicated periods with 100 μg/mL of EHDF. B: Immunofl uorescence microscopy analysis.

3.6. Effects of EHDF-induced up-regulation of HO-1 on the inhibition of pro-inflammatory mediators

As the pre-incubation of macrophages with EHDF resulted in markedly inhibited LPS-stimulated production of pro-infl ammatory mediators (Figure 4), and EHDF was able to induce the expression of HO-1 in a time and dose-dependent manner (Figure 6). Therefore,to confi rm the involvement of HO-1 in the inhibitory eff ects of LPS-induced infl ammation, pro-infl ammatory mediators were examined using SnPP. Macrophage cells were treated with SnPP (50 μM)for 1 h, followed by treatment with LPS (1 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of EHDF at 100 μg/mL. As shown in Figure 8, SnPP partially abolished EHDF suppression of LPS-induced production of pro-infl ammatory mediators including NO, IL-1β, TNF-α and PGE2.

Figure 8. HO-1 mediates suppressive effect of EHDF on LPS-stimulated production of pro-infl ammatory mediators.A: NO production determined by using Griess reagent; B: IL-1β; C: TNF-α; D: PGE2. Compared with indicated group,*P<0.05,***P<0.005.

4. Discussion

H. dulcis Thunberg (Rhamnaceae) is mainly found in China, Japan,and Korea, and is commonly used as a folk remedy in the form of tea and dietary supplements to promote health. Several reports suggested that the fruit of H. dulcis has detoxifi cation properties on alcohol poisoning, hepatoprotective effect, antioxidant and antidiabetic activities[24-27]. Recently, the major biologically active components identifi ed in the fruits of H. dulcis were myricetin and quercetin[23,27]. However, underlying mechanisms to explain the anti-infl ammatory effects of H. dulcis fruits remain unknown. In this study, we investigated the anti-infl ammatory eff ects of the ethanol EHDF in LPS-induced mouse macrophage Raw 264.7 cells. Inflammation is a defense mechanism that living organisms use to protect themselves from various external infections[1]. The infl ammatory response is well known to be regulated by central infl ammatory responses proteins such as iNOS and COX-2[28,29]. Furthermore,macrophages play a critical role in both the infl ammatory responses and overproduction of pro-inflammatory mediators such as NO,PGE2, and cytokines[30-32]. It has been implicated in several inflammation-related diseases including atherosclerosis, cancer,arthritis and autoimmune diseases[33,34]. Our major fi nding is that the ethanol EHDF suppresses NO production. NO is up-regulated in activated LPS-treated macrophage cells, and is secreted during extracellular space gas formation. Also, we demonstrated that the pre-treatment of diff erent concentrations of EHDF (5-100 μg/mL)results in the suppressed expression of iNOS and COX-2 enzymes. In this study, EHDF also potently inhibited various LPS-induced pro-infl ammatory mediators, such as IL-1β, PGE2and TNF-α in a dose-dependent manner. These results suggest that EHDF exerts its anti-infl ammatory eff ects by down-regulating pro-infl ammatory enzymes, and by the suppression of infl ammatory mediators in the macrophages, in the absence of LPS stimulation.

Pro-infl ammatory cytokines are signifi cant transcription factors for infl ammatory response associated enzymes including NF-κB[35]. NF-κB is also a transcription factor controlling the gene expressions involving immune responses and inflammation[9,36]. Therefore,regulation by NF-κB translocation might be considered a major therapeutic target for the treatment of infl ammatory diseases[2,37]. This study evaluated the effects of EHDF on phosphorylation and degradation of IκB-α and nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 induced by LPS, and observed that they were significantly reduced after the pre-treatment of macrophages. One of possible explanations for the inhibitory role of EHDF in pro-infl ammatory mediator production in LPS-induced macrophage cells is that EHDF may interrupt the interaction of LPS to receptors. These fi ndings were similar to those shown in the previously studies[32].

HO-1 participates in maintaining cellular homeostasis and plays an important role in reducing oxidative injury and attenuating the infl ammation in macrophage and tissues[18]. A growing body of evidence shows that HO-1 directly represses inflammatory responses by down regulation of inflammatory mediators such as NO, PGE2, IL-β, and TNF-α[14,38]. The HO-1 gene also can be transcriptionally activated by Nrf2 and NF-κB[39]. When Nrf2 is activated by oxidative stress such LPS, electrophiles and harmful chemicals, it translocates to the nucleus and bind to its cis-acting response[40]. Other previous studies have demonstrated that the Nrf2-dependent activation of antioxidant systems reduces infl ammation[30,41]. In addition, our results suggest that EHDF can activate Nrf2 by promoting the dissociation of the Nrf-2 and subunit complex, resulting in the induction of HO-1 activity. Furthermore,our study clearly demonstrates that treatment with SnPP reverses the inhibitory effects of EHDF on NO, PGE2, IL-1β, and TNF-α αsecretion.

In conclusion, EHDF, the ethanol EHDF, showed potent antiinfl ammatory functions on LPS-stimulated macrophage activation via the Nrf2-mediated up-regulation of HO-1 and inhibition of NF-κB signaling. These fi nding suggest that EHDF might be a potent agent for further investigation in the treatment of infl ammation related diseases.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no confl ict of interest.

[1] Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 2008; 454(7023): 428-435.

[2] Kim HY, Hwang KW, Park SY. Extracts of Actinidia arguta stems inhibited LPS-induced infl ammatory responses through nuclear factorκB pathway in Raw 264.7 cells. Nutr Res 2014; 34(11): 1008-1016.

[3] Lawrence T, Willoughby DA, Gilroy DW. Anti-inflammatory lipid mediators and insights into the resolution of infl ammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2(10): 787-795.

[4] Koo HJ, Yoon WJ, Sohn EH, Han YM, Jang SA, Kown JE, et al. The analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Litsea japonica fruit are mediated via suppression of NF-κB and JNK/p38 MAPK activation. Int Immunopharmacol 2014; 22(1): 84-97.

[5] Yang J, Li S, Xie C, Ye H, Tang H, Chen L, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of ethyl acetate fraction of the seeds of Brucea Javanica. J Ethnopharmacol 2013; 147(2): 442-446.

[6] Lee AK, Sung SH, Kim YC, Kim SG. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharideinducible nitric oxide synthase, TNF-alpha and COX-2 expression by sauchinone eff ects on I-kappaB alpha phosphorylation, C/EBP and AP-1 activation. Br J Pharmacol 2003; 139(1): 11-20.

[7] Ying X, Yu K, Chen X, Chen H, Hong J, Cheng S, et al. Piperine inhibits LPS induced expression of infl ammatory mediators in Raw 264.7 cells. Cell Immunol 2013; 285(1-2): 49-54.

[8] Goodwin JS, Ceuppens J. Regulation of the immune response by prostaglandins. J Clin Immunol 1983; 3(4): 295-315.

[9] Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol 2000; 18: 621-663.

[10] Nam NH. Naturally occurring NF-kappaB inhibitors. Mini Rev Med Chem 2006; 6(8): 945-951.

[11] Ben-Neriah Y. Regulatory functions of ubiquitination in the immune system. Nat Immunol 2002; 3(1): 20-26.

[12] Aggarwal BB. Nuclear factor-kappaB: the enemy within. Cancer Cell 2004; 6(3): 203-208.

[13] Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress,infl ammation, and cancer: How are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med 2010; 49(11): 1603-1616.

[14] Choi S, Nguyen VT, Tae N, Lee S, Ryoo S, Min BS, Lee JH. Anti-infl ammatory and heme oxygenase-1 inducing activities of lanostane triterpenes isolated from mushroom Ganoderma lucidum in Raw264.7 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2014; 280(3): 434-442.

[15] Xu Z, Zhou J, Cai J, Zhu Z, Sun X, Jiang C. Anti-inflammation effects of hydrogen saline in LPS activated macrophages and carrageenan induced paw oedema. J Inflamm (Lond) 2012; 9(1): 2.

[16] Choi HG, Lee DS, Li B, Choi YH, Lee SH, Kim YC. Santamarin, a sesquiterpene lactone isolated from Saussurea lappa, represses LPS-induced infl ammatory responses via expression of heme oxygenase-1 in murine macrophage cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2012; 13(3): 271-279.

[17] Maines MD, Panahian N. The heme oxygenase system and cellular defense mechanisms. Do HO-1 and HO-2 have diff erent functions? Adv Exp Med Biol 2001; 502: 249-272.

[18] Otterbein LE, Bach FH, Alam J, Soares M, Tao Lu H, Wysk M, et al. Carbon monoxide has anti-infl ammatory eff ects involving the mitogenactivated protein kinase pathway. Nat Med 2000; 6(4): 422-428.

[19] Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, et al. An Nrf2/ small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase Ⅱ detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997; 236(2): 313-322.

[20] Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2007; 47: 89-116.

[21] Morse D, Lin L, Choi AM, Ryter SW. Heme oxygenase-1, a critical arbitrator of cell death pathways in lung injury and disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2009; 47(1): 1-12.

[22] Yang J, Wu S, Li C. High effi ciency secondary somatic embryogenesis in Hovenia dulcis Thunb. through solid and liquid cultures. Sci World J 2013; 2013: 1-6.

[23] Park JS, Kim IS, Rehman SU, Na CS, Yoo HH. HPLC determination of bioactive fl avonoids in Hovenia dulcis fruit extracts. J Chromatogr Sci 2015; DOI:10.1093/chromsci/bmv114.

[24] Chen SH, Zhong GS, Li AL, Li SH, Wu LK. Influence of Hovenia dulcis on alcohol concentration in blood and activity of alcohol dehydrogenase(ADH) of animals after drinking. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2006;31(13): 1094-1096.

[25] Hyun TK, Eom SH, Yu CY, Roitsch T. Hovenia dulcis-an Asian traditional herb. Planta Medica 2010; 76(10): 943-949.

[26] Wang M, Zhu P, Jiang C, Ma L, Zhang Z, Zeng X. Preliminary characterization, antioxidant activity in vitro and hepatoprotective eff ect on acute alcohol-induced liver injury in mice of polysaccharides from the peduncles of Hovenia dulcis. Food Chem Toxicol 2012; 50(9): 2964-2970.

[27] Kim HL, Sim JE, Choi HM, Choi IY, Jeong MY, Park J, et al. The AMPK pathway mediates an anti-adipogenic eff ect of fruits of Hovenia dulcis Thunb. Food Funct 2014; 5(11): 2961-2968.

[28] Becker S, Mundandhara S, Devlin RB, Madden M. Regulation of cytokine production in human alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells in response to ambient air pollution particles: further mechanistic studies. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005; 207(suppl 2): 269-275.

[29] Oh YC, Cho WK, Im GY, Jeong YH, Hwang YH, Ma JY. Antiinfl ammatory eff ect of Lycium fruit water extract in lipopolysaccharidestimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2012;13(2): 181-189.

[30] Choi HJ, Choi HJ, Park MJ, Lee JY, Jeong SI, Lee S et al. The inhibitory effects of Geranium thunbergii on interferon-γ- and LPS-induced infl ammatory responses are mediated by Nrf2 activation. Int J Mol Med 2015; 35(5): 1237-1245.

[31] Park EJ, Kim YM, Park SW, Kim HJ, Lee JH, Lee DW. Induction of HO-1 through p38 MAPK/Nrf2 signaling pathway by ethanol extract of Inula helenium L. reduces inflammation in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells and CLP-induced septic mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2013; 55: 386-395.

[32] Li B, Choi HJ, Lee DS, Oh H, Kim YC, Moon JY et al. Amomum tsaoko suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in RAW264.7 macrophages via Nrf2-dependent heme oxygenase-1 expression. Am J Chin Med 2014; 42(5): 1229-1244.

[33] Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related infl ammation. Nature 2008; 454(7203): 436-444.

[34] Drexler SK, Kong PL, Wales J, Foxwell BM. Cell signaling in macrophages, the principal innate immune eff ector cells of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2008; 10(5): 216.

[35] Didonato JA, Mercurio F, Karin M. NF-κB and the link between infl ammation and cancer. Immunol Rev 2012; 246(1): 379-400.

[36] Bonizzi G, Karin M. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol 2004; 25(6): 280-288.

[37] Lee AS, Jung YJ, Kim D, Nguyen-Thanh T, Kang KP, Lee S, et al. Sirt2 ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced infl ammation in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014; 450(4): 1363-1369.

[38] Abraham NG, Kappas A. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of heme oxygenase. Pharmacol Rev 2008; 60(1): 79-127.

[39] Paine A, Eiz-Vesper B, Blasczyk R, Immenschuh S. Signaling to heme oxygenase-1 and its anti-infl ammatory therapeutic potential. Biochem Pharmacol 2010; 80(12): 1895-1903.

[40] Baird L, Dinkova-Kostova AT. The cytoprotective role of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Arch Toxicol 2011; 85(4): 241-272.

[41] Manandhar S, You A, Lee ES, Kim JA, Kwak MK. Activation of the Nrf2-antioxidant system by a novel cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor furan-2-yl-3-pyridin-2-yl-propeone: implication in anti-infl ammatory function by Nrf2 activator. J Pharm Pharmacol 2008; 60(7): 879-887.

ent heading

10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.03.017

15 January 2016

Hyuck Kim, PhD, Visiting professor, Department of Diagnostics, College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Siksa-dong, Ilsan,Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do 10326, Republic of Korea.

Tel: +82 31 961 5832

Fax: +82 31 961 5823

E-mail: hyuckkim@dongguk.ac.kr

Jai-Eun Kim, PhD and K.M.D, Associate professor, Department of Pathology,College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Siksa-dong, Goyang-si, Ilsan,Gyeonggi-do 10326, Republic of Korea.

Tel: +82 31 961 5829

Fax: +82 31 961 5823

E-mail: herbqueen@dongguk.ac.kr

in revised form 20 February 2016

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Determination of ligand cluster and binding site within VP40 of Ebola virus: clue for drug development

- Clinacanthus nutans: a review of the medicinal uses, pharmacology and phytochemistry

- Current perspectives on dengue episode in Malaysia

- Etiological agents causing leptospirosis in Sri Lanka: A review

- Phylogeny of Murray Valley encephalitis virus in Australia and Papua New Guinea

- Dengue outbreak in Swat and Mansehra, Pakistan 2013; an epidemiological and diagnostic perspective