Scientific evidence is just the starting point:A generalizable process for developing sports injury prevention interventions

2016-10-24AlexDonldsonDvidLloydBelindGeJillCookdWrrenYoungePetWhiteCrolineFinh

Alex Donldson*,Dvid G.Lloyd,Belind J.Ge,Jill Cookd,Wrren Younge,Pet WhiteCroline F.Finh

aAustralian Centre for Research into Injury in Sport and its Prevention(ACRISP),Federation University Australia,Ballarat,VIC 3353,Australia

bCentre for Musculoskeletal Research,Griffith Health Institute,Griffith University,Gold Coast,QLD 9726,Australia

cDepartment of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine,Monash University,Melbourne,VIC 3004,Australia

dLa Trobe Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre,La Trobe University,Melbourne,VIC 3083,Australia

eSchool of Health Sciences,Federation University Australia,Ballarat,VIC 3353,Australia

Scientific evidence is just the starting point:A generalizable process for developing sports injury prevention interventions

Alex Donaldsona,*,David G.Lloydb,Belinda J.Gabbec,Jill Cooka,d,Warren Younga,e,Peta Whitea,Caroline F.Fincha

aAustralian Centre for Research into Injury in Sport and its Prevention(ACRISP),Federation University Australia,Ballarat,VIC 3353,Australia

bCentre for Musculoskeletal Research,Griffith Health Institute,Griffith University,Gold Coast,QLD 9726,Australia

cDepartment of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine,Monash University,Melbourne,VIC 3004,Australia

dLa Trobe Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre,La Trobe University,Melbourne,VIC 3083,Australia

eSchool of Health Sciences,Federation University Australia,Ballarat,VIC 3353,Australia

Background:The 2 most cited sports injury prevention research frameworks incorporate intervention development,yet little guidance is available in the sports science literature on how to undertake this complex process.This paper presents a generalizable process for developing implementable sports injury prevention interventions,including a case study applying the process to develop a lower limb injury prevention exercise training program(FootyFirst)for community Australian football.

Methods:The intervention development process is underpinned by 2 complementary premises:(1)that evidence-based practice integrates the best available scientific evidence with practitioner expertise and end user values and(2)that research evidence alone is insufficient to develop implementable interventions.

Results:The generalizable 6-step intervention development process involves(1)compiling research evidence,clinical experience,and knowledge of the implementation context;(2)consulting with experts;(3)engaging with end users;(4)testing the intervention;(5)using theory;and(6)obtaining feedback from early implementers.Following each step,intervention content and presentation should be revised to ensure that the final intervention includes evidence-informed content that is likely to be adopted,properly implemented,and sustained over time by the targeted intervention deliverers.For FootyFirst,this process involved establishing a multidisciplinary intervention development group,conducting 2 targeted literature reviews,undertaking an online expert consensus process,conducting focus groups with program end users,testing the program multiple times in different contexts,and obtaining feedback from early implementers of the program.

Conclusion:This systematic yet pragmatic and iterative intervention development process is potentially applicable to any injury prevention topic across all sports settings and levels.It will guide researchers wishing to undertake intervention development.

©2016 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Australian football;Implementation;Intervention development;Lower limb injuries;Research-to-practice;Sports injury prevention;Translation

1.Introduction

Evidence-based sports injury prevention interventions are not well implemented in real-world settings,1-3often because the interventions are not directly relevant to specific implementation contexts.4,5Interventions should be informed by research evidence and be widely adopted,properly implemented,and sustained over time.4,6

Both the Translating Research into Injury Prevention Practice framework4and the Sequence of Prevention of Sports Injuries model7require practitioners and researchers to identify potential injury prevention solutions and develop appropriate prevention measures guided by high-quality epidemiologic and etiologic studies.Most research remains in the early stages of these models and frameworks,8,9and this limits the potential for injuries to be prevented.In practice,preventive measures are often based on anecdotal experience or current practice,4and the scientific literature rarely provides insights into the complex process of intervention development in real-world settings.10Although systematic reviews and meta-analyses can identify promising interventions,theirconclusionsarerarelydirectlyapplicabletospecificreal-world settings,and translation into effective practice is challenging.11

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2016.08.003

2095-2546/©2016 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Australian football(AF)is a popular sport at the community level inAustralia.It is a dynamic sport that incorporates running,rapid acceleration and deceleration,changing direction,jumping and landing,full body contact including tackling and bumping,and kicking and marking(catching)a ball.As in many other sports,preventing lower limb injuries(LLIs)is a priority in community AF.12Although several evidence-based LLI prevention programs exist,13-15how they were developed is largely unreported,and only 1 targeting selected LLIs is specific to community AF.16For example,the only published information available on the development of the well-known and widely used Fédération Internationale de Football Association(FIFA)“FIFA 11+”program states that it was developed by an expert group,and tested by 1 club,before it was implemented in trials.17

This paper presents a generalizable process for developing evidence-informed sports injury prevention interventions that need to be widely and sustainably implemented in real-world settings.An example application of the process is provided based on the development of an exercise training program(called FootyFirst)to prevent LLIs in community AF.This paper serves as a guide to researchers wishing to progress their research through the intervention development process.

2.Methods

Twocomplementaryideasunderpintheprocessdescribedinthis paper:(1)evidence-based practice integrates the best available scientificevidencewithpractitionerexpertiseandenduservalues,18and(2)research evidence alone is insufficient to develop implementable interventions.2This process addresses the criticism that evidence-based practice devalues practitioner expertise,ignores community values,and promotes a“one-size-fits-all”approach.19It also acknowledges that unless intervention design considers the implementation context,the end user’s perspectives,and long-term sustainability,injury prevention programs are unlikelytobewidelyusedandwillthereforehavelimitedimpact.4,5

Three methods underpinned the application of the intervention development process to FootyFirst:(1)literature search to identify published research evidence,(2)use of clinical expertise and expert opinion via a Delphi process,and(3)focus groups to identify end user preferences,capacities,and values(Table 1).The specific methods used to establish LLIs as a priority,12compile and assess the quality of exercise protocols aimed at reducing LLIs in similar sports,20and achieve expert consensus on the contents of FootyFirst21are described elsewhere.Federation University Australia(E13-004)Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol.

3.Results

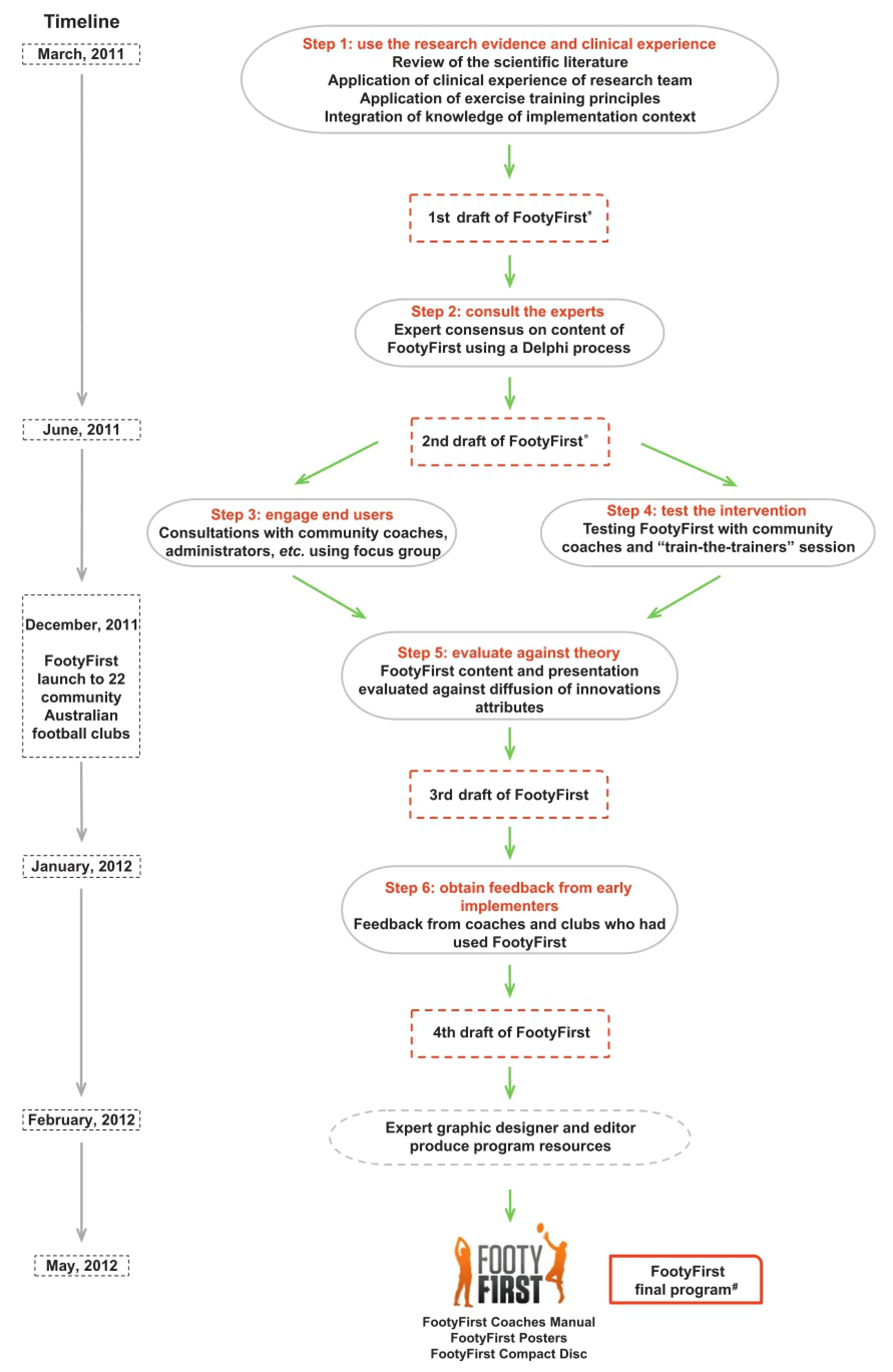

The intervention development process can be encapsulated in 6 steps(Fig.1).The application of these steps and the outcomes of each step when developing FootyFirst are summarized in Fig.2 and Table 2.

As recommended in Translating Research into Injury Prevention Practice Stage 3,4a multidisciplinary FootyFirst Development Group(FFDG)was established,consisting of 2 sports physiotherapists(authors JC and BJG),1 biomechanist(author DGL),1 sports scientist(author WY),and their research teams. Alongside their clinical and research experience,the FFDG had considerable exercise and rehabilitation experience in community and elite sport as well as involvement in previous community AF LLI prevention research.16

3.1.Step 1:use the research evidence and clinical experience

This initial step is necessary to maximize the likelihood that the developed intervention will“work”by ensuring firmgrounding in the available epidemiologic and etiological evidence.To begin the development of FootyFirst,the FFDG systematically evaluated the strength and quality of the evidence on the benefits of exercise protocols with the potential to reduce common community AF LLIs(March to May,2011).20In summary,the collated research evidence suggested that an LLI prevention program should include balance and control and eccentric hamstring,plyometric,and strength exercises.20However,specific details of effective training routines were often unavailable,many studies focused on elite athletes,and there was limited evidence for the prevention of some LLIs.

The FFDG used the synthesized research evidence,their collective clinical and research experience,knowledge of existing LLI prevention protocols and exercise training principles(e.g.,progressive overloading,specificity,and regularity),and prior experience with community AF to develop the first draft of FootyFirst.For example,the research evidence on exercises to prevent hamstring injuries was quite conclusive,20requiring minor modification to suit communityAF.Conversely,research evidence was sparse for hip and groin injury prevention,requiring greater reliance on etiologic studies and clinical experience.

Fig.1.Six-step intervention development process.

3.2.Step 2:consult the experts

This step ensures that the developed intervention is specific to the sport and injury mechanisms of interest.In the case of FootyFirst,the extent to which the information gathered in Step 1 could be translated into the AF context was unknown.Therefore,55 purposively selected LLI prevention experts working in highperformance AF clubs and other environments were invited to participateinanonlineconsensus-generatingapproachtocritically assess the content of the first draft of FootyFirst(June to July,2011).21Three rounds of revisions and consultations went into creating the second draft of FootyFirst,which the FFDG was then confident contained the“right”exercises and progressions. However,whether it“fitted”the communityAF context remained unknown.

3.3.Step 3:engage end users

Development of any intervention requires that the proposed strategies and program components are relevant and acceptable to potential program deliverers(e.g.,strength and conditioning staff,coaches,etc.)and participants(e.g.,athletes,players,etc.).5,6Two focus groups—one with 3 participants from clubs in a metropolitan region and the other with 12 participants from clubs in a regional league—were conducted(July and August,2011)to engage potential end users of FootyFirst in determining whether the program was suitable for implementation by community AF coaches.Participants were recruited with the assistance of administrators from the relevant local governing league and included community AF coaches,strength and conditioning/fitness/high-performance staff,sports trainers,administrators,and players.Participants reviewed the expertagreed version of FootyFirst before discussing its content and presentation,the methods that would be required to support communityAF clubs and coaches to implement FootyFirst,and the capacity of end users to deliver or complete FootyFirst.

Fig.2.Application of the 6-step intervention development process to FootyFirst.*Details of these drafts available in Appendix(online).#Available at https://Footyfirstaustralia.wordpress.com/footyfirst-program.

Focus group findings suggested that there was general supportforreplacingcurrentwarm-upprogramswithFootyFirst. Minor revisions to the way in which FootyFirst was presented were suggested,and ideas to facilitate its implementation wereprovided.Discussants reported similarities between the warm-up component of FootyFirst and their existing pretraining activities. However,most of the strength and conditioning and neuromuscular training exercises were considered less compatible with existing communityAF training.Participants indicated that most clubs had experienced or qualified people to deliver FootyFirst,although help with implementing the program into training sessions was needed.They also advocated for including a rationale for each exercise to help coaches promote FootyFirst to their players.Finally,although they acknowledged and appreciated that FootyFirst was underpinned by scientific evidence,focus group participants suggested that FootyFirst should also be endorsed by respected,high-performance AF coaches and the peak body,the Australian Football League(AFL).

Table 2 The process and outcomes of developing FootyFirst,from the initial exercise selection to the final protocol and resource production.

Participants identified other implementation-related issues that needed to be considered when developing FootyFirst,including the following:

·time available to complete the intervention(typically 15-20 min);

·equipment available to implement the intervention in a typical club;

·capacity of community AF players to perform some of the entry-level exercises;

·concern that some exercises might increase the risk of injury and/or muscle soreness;and

·the challenge of implementing a progressive exercise training program with players within a single team/club with varying fitness levels and training commitment.

Consequently,the structure of some FootyFirst exercises was revised to align more closely with typical communityAF training activities while maintaining their fidelity from a clinical and biomechanical perspective.The AFL logo,a foreword or introduction from a high-performance AF coach,and a“frequently asked questions”section were also added to the FootyFirst instruction manual.

3.4.Step 4:test the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention

Before assessing intervention efficacy,the feasibility and acceptability of an intervention should be tested to be confident that it can be delivered as intended and that participants can successfully complete all required tasks.In the case ofFootyFirst,the postexpert consultation version of the program(2nd draft in Fig.2 and Table 2)was tested on several occasions by the FFDG.First,6 exercise science and physiotherapy students,who were all community-level athletes,were videotaped and photographed performing the exercises correctly and incorrectly(August,2011).This led to further refinement of some exercise instructions and the addition of photographs and descriptions of common technique faults in the program resources.

The intervention was then tested again.A coach was given the revised FootyFirst instruction manual and observed while delivering the intervention to 2 community AF players(October,2011).The aim was to determine whether a typical community AF coach who had preread the instruction manual could deliver it as intended.The time taken to complete the program was reviewed to ensure compatibility with the time allocated to complete pretraining activities at a typical community AF training session.This test highlighted the need to emphasize proper technique in the instructions,and it showed that additional rest periods were required between repetitions for some exercises.Importantly,it also identified that some exercises needed modifications(e.g.,reduction in number of sets or repetitions)to reduce the time taken to complete them. Further minor word changes were also made to improve clarity and assist intervention delivery.

High levels of trainer competency and self-efficacy are acknowledged drivers of implementation success.22,23Therefore,a key strategy for enhancing FootyFirst implementation within targeted community AF clubs was training coaches how to deliver the intervention to players.24A“train-the-trainer”session was held to explain FootyFirst to a respected,highprofile,high-performance coach affiliated with a community AF club in the targeted region.This coach was observed as he delivered the intervention to 2 community AF players and was provided with feedback(January,2012).Following the trainthe-trainer session,it became apparent that the progression for 1 particular exercise might be too difficult for some community AF players,and a new exercise was added to ensure adequate preparation for the transition between levels.Minor revisions were also made to the instructions and photographs for some exercises.

3.5.Step 5:evaluate against theory

When developing an intervention,one-way to enhance the likelihood of its adoption,implementation,and maintenance by the target audience in the real-world setting is to evaluate it against a relevant theory.To further fit FootyFirst into the community AF context,the research team evaluated the program content and presentation against the relative advantage,compatibility,and complexity attributes of innovations as outlined in the diffusion of innovations theory25during a structured round-table discussion(December,2011).The diffusion of innovations theory was selected because it is specifically applicable to the introduction of new ideas into communities26and is one of the few theories that has been previously applied in sports injury prevention research.24,27,28

Followingthisdiscussion,theinjurypreventionand performance-related advantages of FootyFirst over current warm-up activities were further emphasized in the instruction manual.FootyFirst’s compatibility with the existing values and practices of community AF clubs was also highlighted by explicitly stating that FootyFirst would take<20 min to complete and could replace,rather than be added to,existing warm-up activities.More extensive use of footballs in some exercises was also instituted to enhance compatibility with typical AF game components.FootyFirst was also promoted as a way to align community AF training more closely with training at high-performance AF clubs by adding endorsements from a respected high-performance AF coach and the AFL Medical Officers Association.The complexity of the program was considered by ensuring that all exercises were explained clearlyandstraightforwardlyandbyemphasizingthat FootyFirst did not require any expensive or sophisticated equipment.

3.6.Step 6:obtain feedback from early implementers

Despite all the effort invested in Steps 1-5,it is not guaranteed that the process will develop a perfect intervention,especially at the first attempt.Therefore,it is useful to ask end users to use the intervention in their settings and obtain feedback from them about the content and presentation before the intervention is formally evaluated.The post-theory-evaluated version of FootyFirst(3rd draft in Fig.2 and Table 2)was launched and disseminated to 22 communityAF clubs affiliated with 1 AF regional league in Victoria,Australia(December,2011).This provided an opportunity to obtain feedback from early implementers of the program prior to the football season. Eligible clubs and coaches were asked to suggest revisions to the program before final resource production(February,2012).

No further changes to the program content were suggested,although minor changes were made to the language and presentation where inconsistencies were identified.A professional editor/graphic designer was then engaged to produce the final FootyFirst resources,which were distributed to the 22 targeted clubs(March,2012).Video footage of the FootyFirst exercises was produced,in partnership with theAFL,and made available to participating clubs in DVD and online formats prior to the 2013 community AF season.29

4.Discussion

Although developing preventive measures is integral to the 2 most widely used sports injury prevention research frameworks,4,7to our knowledge,this is the first detailed description of a process to achieve this.This paper provides a step-by-step generalizable guide on how to develop evidenceinformed and context-specific interventions.The guide confirms that intervention development is a complex,iterative process requiring a balancing of evidence and experience.30

Physical training is the second most studied sports injury prevention intervention,9yet when Step 1 of the intervention development process was applied to FootyFirst,it was identified that the scientific evidence underpinning physical training as aninjury prevention intervention is limited.20Randomized controlled trials to reduce injury rates may be ineffective because the principles underpinning the trialed prevention strategies were not based on the evidence of injury etiology and mechanisms,or because the implementation context was not adequately considered during the intervention development process.4,31,32These issues are common in sports medicine,4,9and in public health more broadly,33and both are addressed by the proposed intervention development process(in Steps 1 and 3 specifically).

Step 2 provides a practitioner-expert perspective on the intervention under development.This is particularly valuable when full scientific evidence about what might work is either absent from,or limited in,the scientific literature and intervention developers need to rely on critical evaluation of the intervention by others in the field.In the example of FootyFirst,the expert consensus opinion generally reflected the available scientific evidence.The exercises that were more strongly supported by published evidence remained largely unchanged.The round in which consensus was reached on each exercise was commensurate with the level of evidence available.20,21A side benefit of this expert consultation was that it assisted in attaining endorsement of FootyFirst from relevant experts working in high-performance AF.

The intervention development process and its application to the development of FootyFirst highlighted that the intervention content experts often lacked expertise in effectively communicating those interventions to the target audience.The FFDG focused initially on ensuring that scientific evidence and exercise training and biomechanical principles underpinned the program content,rather than precisely describing the exercises. Interpretation difficulties experienced while testing the intervention(Step 4 specifically)were not anticipated by the FFDG,nor were they identified during either the expert(Step 2)or end user(Step 3)consultations.Participants in the end user consultations were asked if they understood the instructions and whether they believed that community AF players could complete the exercises.They were not asked if they understood exactly how to do the exercises.The challenges experienced while testing FootyFirst highlight the distinction between generally understanding an intervention and being able to deliver or instruct someone else to participate in it with high fidelity.

Although some program planning frameworks recommend that potential program participants are involved right from the needs assessment/problem identification stage,6in the sports medicine and science context,end users are not typically directly engaged in the intervention development process outlined in this paper until Step 3.However,this should not preclude intervention developers from confirming earlier that the injury issue being addressed is important and ensuring that the proposed method of intervention is acceptable from the end user’s perspective.This may be particularly relevant when addressing injury issues or proposing intervention methods that are less well documented than for LLIs in team ball sports.It may also be advantageous to gain feedback from the end users when critically evaluating a proposed intervention against a theory or model(Step 5).

Step 4 in the intervention development process focuses on testing the intervention.In our experiences with FootyFirst,this was challenging owing to the short break between the end of 1 communityAF season and the start of preseason training for the next season(often as little as 6 weeks).FootyFirst was not tested with a full community AF team,and coaches were not observed delivering it to their teams before the program was made publically available.Only small-scale tests of the program were possible,which did not reflect its intended real-world use. Furthermore,the program required participants to progress from one level to another over a relatively short period of time and a number of training sessions.Even after the evidence underpinning the content of a program is confirmed,intervention development is a long and time-consuming process,ideally involving long lead times with early testing of the proposed interventions within the target setting.

Following the development of an intervention,it is important to develop an evidence-informed and context-specific implementation plan to facilitate uptake of the intervention by end users.24,28The effectiveness of the intervention and implementation plan should then be evaluated under both ideal and realworld conditions.4

5.Conclusion

Sports scientists,sports medicine clinicians,and sports injury prevention researchers need to be competent in developing interventions that are informed by the best available research evidence,suitable for the context in which they are to be implemented,and compatible with the needs,capacity,and values of potential end users.The 6-step intervention development process outlined here provides,for the first time,a practical,feasible,and generalizable process for doing this.It is applicable to intervention development across a range of topics and sports settings and levels.

Acknowledgments

Thanks toAlasdair Dempsey,Clare Minahan,Jane Grayson,Jace Kelly,and NadineAndrew for their contributions to developing FootyFirst.We also thank all the experts and community Australian football representatives who participated in consultations and testing of FootyFirst.

This study was funded by an National Health and Medical Research Council(NHMRC)Partnership Project Grant(ID:565907)which included additional support(both cash and in-kind)from the following project partner agencies:the Australian Football League;Victorian Health Promotion Foundation;New South Wales Sporting Injuries Committee;JLT Sport,a division of Jardine LloydThompsonAustralia Pty Ltd.;Sport and Recreation Victoria,Department of Transport,Planning and Local Infrastructure;and Sports MedicineAustralia—National andVictorian Branches.Caroline Finch was supported by an NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship(APP1058737). Belinda Gabbe was supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship(APP1048731).Jill Cook was supported by a NHMRC Practitioner fellowship(APP1058493).Alex Donaldson and Peta White held Research Fellowships funded through the major NHMRC Partnership Project Grant.

CFF,DGL,BJG,JC,and AD conceived of and planned the study.BJG coordinated the literature review with support from DGL and JC.DGL,BJG,JC,and WY developed the first draft of FootyFirst and contributed to all stages of the program’s revision.AD coordinated and conducted the expert consultation,end user engagement,feedback from early implementers of FootyFirst and production of final FootyFirst program material.AD coordinated and all authors contributed to the evaluation against theory.DGL and WY coordinated the testing of FootyFirst with support from BJG and JC.PW coordinated the early stages of the development of FootyFirst and gathered the background information for the manuscript.AD conceived the“6-step process for developing sports injury prevention interventions”with feedback from all authors.All authors contributed to early drafts of the manuscript and have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

None of the authors declare competing financial interests.

Appendix:Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2016.01.029

1.Bahr R,Thorborg K,Ekstrand J.Evidence-based hamstring injury prevention is not adopted by the majority of Champions League or Norwegian Premier League football teams:the Nordic Hamstring survey. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1466-71.

2.Hanson D,Allegrante JP,Sleet DA,Finch CF.Research alone is not sufficient to prevent sports injury.Br J Sports Med 2014;48:682-4.

3.Twomey D,Finch C,Roediger E,Lloyd DG.Preventing lower limb injuries:is the latest evidence being translated into the football field?J Sci Med Sport 2009;12:452-6.

4.Finch C.A new framework for research leading to sports injury prevention. J Sci Med Sport 2006;9:3-9.

5.Donaldson A,Finch CF.Planning for implementation and translation:seek first to understand the end-users’perspectives.Br J Sports Med 2012;46:306-7.

6.Bartholomew LK,Parcel GS,Kok G,Gottilieb NH,Fernandez ME. Planning health promotion programs.An intervention mapping approach. 3rd ed.San Francisco,CA:Jossey-Bass;2011.

7.van Mechelen W,Hlobil H,Kemper HC.Incidence,severity,aetiology and prevention of sports injuries:a review of concepts.Sports Med 1992;14:82-99.

8.Chalmers DJ.Injury prevention in sport:not yet part of the game?Inj Prev 2002;8:22-5.

9.Klügl M,Shrier I,McBain K,Shultz R,Meeuwisse WH,Garza D,et al. The prevention of sport injury:an analysis of 12,000 published manuscripts.Clin J Sport Med 2010;20:407-12.

10.Schaalma H,Kok G.Decoding health education interventions:the times are a-changin’.Psychol Health 2009;24:5-9.

11.Wilson-Simmons R,O’Donnell L.Encouraging adoption of science-based interventions:organizational and community issues.In:Doll L,Bonzo S,Sleet D,editors.Handbook of injury and violence prevention.New York,NY:Springer Science+Business Media;2007.p.511-25.

12.Finch CF,Gabbe B,White P,Lloyd D,Twomey D,Donaldson A,et al. Priorities for investment in injury prevention in community Australian football.Clin J Sport Med 2013;23:430-8.

13.Hübscher M,Refshauge KM.Neuromuscular training strategies for preventing lower limb injuries:what’s new and what are the practical implications of what we already know?Br J Sports Med 2013;47:939-40.

14.Hübscher M,Zech A,Pfeifer K,Hänsel F,Vogt L,Banzer W. Neuromuscular training for sports injury prevention:a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:413-21.

15.Emery CA,Roy TO,Whittaker JL,Nettel-Aguirre A,van Mechelen W. Neuromuscular training injury prevention strategies in youth sport:a systematic review and meta-analysis.Br J Sports Med 2015;49:865-70.

16.Finch CF,Twomey DM,Fortington LV,Doyle TL,Elliott BC,Akram M,et al.PreventingAustralian football injuries with a targeted neuromuscular control exercise programme:comparative injury rates from a training intervention delivered in a clustered randomised controlled trial.Inj Prev 2015.doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041667

17.Soligard T,Myklebust G,Steffen K,Holme I,Silvers H,Bizzini M,et al. Comprehensive warm-up programme to prevent injuries in young female footballers:cluster randomised controlled trial.BMJ 2008;337:a2469. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2469

18.Haynes RB,Devereaux PJ,Guyatt GH.Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based medicine and patient choice.Evid Based Med 2002;7:36-8.

19.Straus SE,McAlister FA.Evidence-based medicine:a commentary on common criticisms.CMAJ 2000;163:837-41.

20.Andrew N,Gabbe BJ,Cook J,Lloyd DG,Donnelly CJ,Nash C,et al. Could targeted exercise programmes prevent lower limb injury in community Australian football?Sports Med 2013;43:751-63.

21.Donaldson A,Cook J,Gabbe B,Lloyd DG,Young W,Finch CF.Bridging the gap between content and context:establishing expert consensus on the content of an exercise training program to prevent lower-limb injuries.Clin J Sport Med 2015;25:221-9.

22.Donaldson A,Finch CF.Applying implementation science to sports injury prevention.Br J Sports Med 2013;47:473-5.

23.Padua DA,Frank B,Donaldson A,de la Motte S,Cameron KL,Beutler AI,et al.Seven steps for developing and implementing a preventive training program:lessons learned from JUMP-ACL and beyond.Clin Sports Med 2014;33:615-32.

24.Donaldson A,Lloyd DG,Gabbe BJ,Cook J,Finch FC.We have the programme,what next?Planning the implementation of an injury prevention programme.Inj Prev 2016;pii:injuryprev-2015-041737.doi:10.1136/ injuryprev-2015-041737

25.Rogers E.Diffusion of innovations.5th ed.New York,NY:Free Press;2003.

26.Nutbeam D,Harris E.Theory in a nutshell:a practical guide to health promotion theories.2nd ed.Sydney:McGraw Hill;2004.p.23-7.

27.McGlashan AJ,Finch CF.The extent to which behavioural and social sciences theories and models are used in sport injury prevention research. Sports Med 2010;40:841-58.

28.Donaldson A,Poulos RG.Planning the diffusion of a neck-injury prevention programme among community rugby union coaches.Br J Sports Med 2014;48:151-9.

29.Donaldson A.FootyFirst Program.[NOGAPS:National Guidance forAustralian Football Partnerships and Safety].June 17,2015.Available at:https://footyfirstaustralia.wordpress.com/footyfirst-program/;[accessed 17.08.2016].

30.Malterud K.The art and science of clinical knowledge:evidence beyond measures and numbers.Lancet 2001;358:397-400.

31.Finch CF,Gabbe BJ,Lloyd DG,Cook J,Young W,Nicholson M,et al. Towards a national sports safety strategy:addressing facilitators and barriers towards safety guideline uptake.Inj Prev 2011;17:1-10.

32.Donnelly CJ,Elliott BC,Ackland TR,Doyle TL,Beiser TF,Finch CF,et al.An anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention framework:incorporating the recent evidence.Res Sports Med 2012;20:239-62.

33.Sanson-Fisher RW,Campbell EM,Htun AT,Bailey LJ,Millar CJ.We are what we do:research outputs of public health.Am J Prev Med 2008;35:380-5.

34.Kitzinger J.Qualitative research.Introducing focus groups.BMJ 1995;311:299-302.

.

E-mail address:a.donaldson@federation.edu.au(A.Donaldson).

s’contributions

12 February 2016;revised 13 May 2016;accepted 23 May 2016 Available online 3 August 2016

杂志排行

Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Physical activity and health in the presence of China’s economic growth:Meeting the public health challenges of the aging population

- Physical activity and cognitive function among older adults in China:A systematic review

- Effects of Tai Ji Quan training on gait kinematics in older Chinese women with knee osteoarthritis:A randomized controlled trial

- Recruitment of older adults into randomized controlled trials:Issues and lessons learned from two community-based exercise interventions in Shanghai

- Associations between individual and environmental factors and habitual physical activity among older Chinese adults:A social-ecological perspective

- Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis mechanisms and prevention:A literature review