Letters to the Editor

2016-08-26TomasSBexelius,RickardLjung

Letters to the Editor

The Editor welcomes submissions for possible publication in the Letters to the Editor section.

Letters commenting on an article published in the Journal or other interesting pieces will be considered if they are received within 6 weeks of the time the article was published. Authors of the article being commented on will be given an opportunity to offer a timely response to the letter. Authors of letters will be notified that the letter has been received. Unpublished letters cannot be returned.

Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and acute pancreatitis

To the Editor:

The incidence of acute pancreatitis is increasing,[1]about 30-70 per 100 000 person-years in the Western world,with the highest rates in the United States, where diabetes and metabolic syndrome are common. Type 2 diabetes is a part of the metabolic syndrome, which is associated with a subsequent increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Several components of the metabolic syndrome have been reported to increase the risk of acute pancreatitis, including type 2 diabetes,[2-5]obesity,[6]dyslipidemia, and hypertension.[7]We aimed to clarify the association between type 2 diabetes and acute pancreatitis. We also took conditions of the metabolic syndrome into account as that may have confounded the relationship reported in previous studies between type 2 diabetes and acute pancreatitis.

We conducted a population-based, nested case-control study. The cohort is from The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database in the United Kingdom from January 1, 1996 to September 30, 2005.[8, 9]The study design is more thoroughly described in a previous paper.[8]

Patients registered for at least two years in the database were considered for the study. Patients with previous pancreatic disease or history of cancer were excluded. Hypertensive patients, which was diagnosed using codes from the Read clinical classification system,[10]between 40-79 years old, were identified via a computerized search, based on the same diagnostic criteria used in clinical practice among general practitioners (GPs) in the United Kingdom.

Exposure to type 2 diabetes was defined as the presence of a Read diagnosis code. Components of the metabolic syndrome was defined using the International Diabetes Federation from 2006:[11]presence of obesity (body mass index >30 kg/m2), hypertension (defined above), dyslipidemia (diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia or current treatment with statins), raised fasting plasma glucose, defined as presence of type 2 diabetes.[12]

First-time cases of acute pancreatitis, no matter the etiology were identified through a computerized search based on diagnosis code. One investigator (BTS), blinded to the exposure data, manually reviewed the patient profiles, to ascertain the potential cases. Patients were classified as cases if any of the following conditions were present: acute pancreatitis (from the discharge letter),clinical signs of acute pancreatitis together with at least one of the following two criteria: a) >2 times above the normal reference range of serum pancreatic enzyme level (amylase and/or lipase) or b) confirmatory investigations. Only cases where the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis was certain were included. In a subset of 50 suspected cases their GP validated the diagnosis. Two cases were excluded, rendering a positive predictive value of acute pancreatitis of 96%, which was comparable to the result of a Swedish validation study.[13]Exposure data on disease and medications was collected before and up to an index date; this was set as the first date of symptoms compatible with acute pancreatitis for cases; for controls it was a randomly assigned date during the study period. A total of 2000 controls individuals were randomly selected based on frequency matching by gender, age and calendar year.

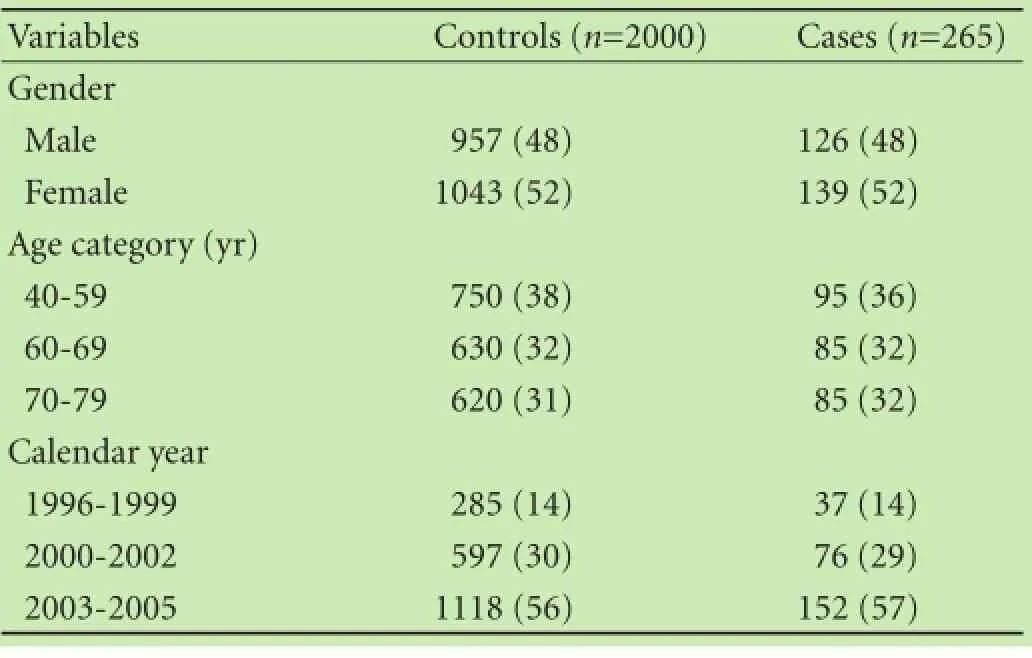

Table 1. Basic characteristics of study participants (n, %)

Relative risk was estimated by calculating odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using unconditional logistic regression. The following covariates were considered: age group (40-59, 60-69 and 70-79 years),calendar year (divided into categories of 1996-1999,2000-2002 and 2003-2005), alcohol consumption (weekly units in categories of 0-2, 3-15, 16-35 and >35), tobacco smoking status (current, non, former, or missing) and number of visits in the previous year to their GP, divided into 0-2, 3-5, 6-10 and >10. Three models of adjustment were decided beforehand. Model 1 included the matching variables only, i.e. gender, age, and calendar year. Model 2 included the matching variables, obesity, and dyslipidemia. Model 3 also included smoking, alcohol consumption, and number of annual GP visits, as a mea-surement of general comorbidity.

Initially, 281 patients were retained as incident cases of acute pancreatitis in a cohort of 167 407 hypertensive patients. Manual review excluded 16 patients due to pancreatic cancer (n=2), chronic pancreatitis (n=4), pancreatic insufficiency (n=1), only raised pancreatic enzyme levels without other symptoms or findings (n=4), and other pancreatic disease (n=5), leaving 265 patients for final analysis. The matching variables were evenly distributed among cases and controls (Table 1).

Adjusting for matching variables (model 1), type 2 diabetes showed a statistically significantly increased OR of 1.44 (95% CI: 1.01-2.03). Adding obesity and dyslipidemia (model 2), type 2 diabetes was not statistically significantly associated with acute pancreatitis (OR=1.36,95% CI: 0.94-1.96). Additionally including alcohol consumption, tobacco smoking, and number of annual GP visits (model 3) the OR was 1.01 (95% CI: 0.75-1.61). Obesity was positively associated with acute pancreatitis (adjusted OR of 1.35, 95% CI: 1.02-1.80) (Table 2).

Type 2 diabetes did not remain a risk factor for acute pancreatitis after adjustment for relevant comorbidity in a cohort of hypertensive patients in THIN. The strengths of the study include validated and population-based data,minimizing selection bias, and prospectively collected exposure data, avoiding recall bias. We have manually validated the acute pancreatitis cases to minimize misclassification, rendering a high positive predictive value (96%). THIN contains information on potential confounders for pancreatitis, like smoking, alcohol consumption and comorbidity, however, residual confounding could still be an issue.

Previous reports on the association between type 2 diabetes and acute pancreatitis have not completely adjusted for all components of the metabolic syndrome.[2-4]In one study[3]using a US health care claims database there were no access to common risk factors like alcohol use, body mass index and current medications, which could have confounded their finding. Moreover, a cohort study conducted in the General Practitioners Database[4]and another study[14]found a significant increased risk among type 2 diabetes patients, but did not adjust for hypertension. As hypertension increases the risk of acute pancreatitis[7, 8]and is related to type 2 diabetes this could confound the relationship between diabetes and acute pancreatitis if not properly handled. Obesity confers higher risk of acute pancreatitis, potentially via a proinflammatory response.[6, 15]Another limitation is the use of statins and dyslipidemia, due to the fact that we didn' t have data on i.e. hypertriglyceridemia, and high density lipoprotein-cholesterol, which would have been a more accurate definition of hypertriglyceridemia as part of the metabolic syndrome.

In conclusion, type 2 diabetes did not increase risk of acute pancreatitis in this cohort of hypertensive patients after adjustment for other components of the metabolic syndrome and relevant comorbidities.

Table 2. Distribution of components of the metabolic syndrome among cases and controls, and their respective relative risk estimated by odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of acute pancreatitis (n, %)

Tomas S Bexelius

Upper Gastrointestinal Research,

Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery,and Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics,

Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Rickard Ljung

Department of Environmental Medicine,

Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Luis A Garcia Rodriguez Centro Español de Investigación Farmacoepidemiológica,

Madrid, Spain

References

1 Spanier BW, Dijkgraaf MG, Bruno MJ. Epidemiology, aetiology and outcome of acute and chronic pancreatitis: An update.Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2008;22:45-63.

2 Gonzalez-Perez A, Schlienger RG, Rodríguez LA. Acute pancreatitis in association with type 2 diabetes and antidiabetic drugs: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2580-2585.

3 Noel RA, Braun DK, Patterson RE, Bloomgren GL. Increased risk of acute pancreatitis and biliary disease observed in patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2009;32:834-838.

4 Girman CJ, Kou TD, Cai B, Alexander CM, O'Neill EA, Williams-Herman DE, et al. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus have higher risk for acute pancreatitis compared with those without diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2010;12:766-771.

5 Shen HN, Lu CL, Li CY. Effect of diabetes on severity and hospital mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis: a national population-based study. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1061-1066.

6 Blomgren KB, Sundström A, Steineck G, Wiholm BE. Obesity and treatment of diabetes with glyburide may both be risk factors for acute pancreatitis. Diabetes Care 2002;25:298-302.

7 Eland IA, Sundström A, Velo GP, Andersen M, Sturkenboom MC, Langman MJ, et al. Antihypertensive medication and the risk of acute pancreatitis: the European case-control study on drug-induced acute pancreatitis (EDIP). Scand J Gastroenterol 2006;41:1484-1490.

8 Sjöberg Bexelius T, García Rodríguez LA, Lindblad M. Use of angiotensin II receptor blockers and the risk of acute pancreatitis:a nested case-control study. Pancreatology 2009;9:786-792.

9 Lewis JD, Schinnar R, Bilker WB, Wang X, Strom BL. Validation studies of the health improvement network (THIN) database for pharmacoepidemiology research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:393-401.

10 Chisholm J. The Read clinical classification. BMJ 1990;300:1092. 11 International Diabetes Feberation (IDF). The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome [serial online]. Available from: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/ IDF_Meta_def_final.pdf

12 Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI,Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association;World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society;and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009;120:1640-1645.

13 Razavi D, Ljung R, Lu Y, Andrén-Sandberg A, Lindblad M. Reliability of acute pancreatitis diagnosis coding in a National Patient Register: a validation study in Sweden. Pancreatology 2011;11:525-532.

14 Lai SW, Muo CH, Liao KF, Sung FC, Chen PC. Risk of acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes and risk reduction on anti-diabetic drugs: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1697-1704.

15 Lankisch PG, Schirren CA. Increased body weight as a prognostic parameter for complications in the course of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 1990;5:626-629.

Published online July 13, 2016.

( 10.1016/S1499-3872(16)60117-0)

Email: tomas.s.bexelius@ki.se

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International

- Dietary supplementation in patients with alcoholic liver disease: a review on current evidence

- Combined hepatectomy and radiofrequency ablation versus TACE in improving survival of patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC

- Effects of Salmonella infection on hepatic damage following acute liver injury in rats

- Long-term follow-up of children and adolescents with primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis

- Kidney transplantation after liver transplantation