Long-term follow-up of children and adolescents with primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis

2016-08-26VratislavSmolkaEvaKaraskovaOksanaTkachykKvetoslavaAiglovaJiriEhrmannKamilaMichalkovaMichalKonecnyandJanaVolejnikovaOlomoucCzechRepublic

Vratislav Smolka, Eva Karaskova, Oksana Tkachyk, Kvetoslava Aiglova, Jiri Ehrmann,Kamila Michalkova, Michal Konecny and Jana VolejnikovaOlomouc, Czech Republic

Long-term follow-up of children and adolescents with primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis

Vratislav Smolka, Eva Karaskova, Oksana Tkachyk, Kvetoslava Aiglova, Jiri Ehrmann,Kamila Michalkova, Michal Konecny and Jana Volejnikova

Olomouc, Czech Republic

BACKGROUND: Sclerosing cholangitis (SC) is a chronic cholestatic hepatobiliary disease with uncertain long-term prognosis in pediatric patients. This study aimed to evaluate longterm results in children with SC according to the types of SC.

METHODS: We retrospectively followed up 25 children with SC over a period of 4-17 years (median 12). The diagnosis of SC was based on biochemical, histological and cholangiographic findings. Patients fulfilling diagnostic criteria for probable or definite autoimmune hepatitis at the time of diagnosis were defined as having autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis (ASC); other patients were included in a group of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). The incidence of the following complications was studied: obstructive cholangitis, portal hypertension, advanced liver disease and death associated with the primary disease.

RESULTS: Fourteen (56%) patients had PSC and 11 (44%)had ASC. Patients with ASC were significantly younger at the time of diagnosis (12.3 vs 15.4 years, P=0.032) and had higher IgG levels (22.7 vs 17.2 g/L, P=0.003). The mentioned complications occurred in 4 (16%) patients with SC, exclusively in the PSC group: one patient died from colorectal cancer, one patient underwent liver transplantation and two patients, in whom severe bile duct stenosis was present at diagnosis, were endoscopically treated for acute cholangitis. Furthermore, two other children with ASC and 2 children with PSC had elevated aminotransferase levels. The 10-year overall survival was 95.8% in all patients, 100% in patients without complicated liver disease, and 75.0% in patients with complications.

CONCLUSION: In children, ASC is a frequent type of SC, whose prognosis may be better than that in patients with PSC.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2016;15:412-418)

autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis;

childhood;

inflammatory bowel disease;

primary sclerosing cholangitis;

prognosis

Introduction

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic cholestatic hepatobiliary disease characterized by inflammation with progressive obliterating fibrosis of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. The reported incidence of PSC in children is 0.2 per 100 000,differing from adults, in whom the incidence is 1.1 per 100 000.[1]Clinical, biochemical and immunological presentations of PSC in children and adolescents differ in many ways from symptoms seen in adult patients with this disease.[2, 3]In children and adolescents, sclerosing cholangitis (SC) often manifests as a cholestatic liver disease with significant autoimmune characteristics, i.e.,autoimmune hepatitis (AIH)/SC overlap syndrome or autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis (ASC), fulfilling the criteria established by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) for definitive or probable diagnosis of AIH.[4, 5]There is currently no effective treatment for patients with PSC, which could prevent gradual progression of liver disease to biliary cirrhosis and chronic liver failure. Liver transplantation remains the only treat-ment, and about 17%-21% of patients with PSC and approximately the same number of children with ASC undergo this operation in the course of the disease.[6-8]Immunosuppressive therapy is effective for ASC; however, there is no definite evidence that the long-term prognosis of patients with ASC is better than that of patients with PSC.[4]Thus, we retrospectively evaluated children with PSC and ASC, and compared their laboratory and histological results at the time of diagnosis as well as the incidence of complications during the course of followup and long-term prognosis.

Statistical analysis was performed using the software SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Fisher' s exact test was used to compare categorical values. Biochemical results, age and duration of follow-up were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the interval from diagnosis to the onset of complications as well as the 5-and 10-year survival rates, which were presented as point estimation of survival with standard error of survival value. Cox regression was used for univariate analysis.

Methods

The patients diagnosed with PSC and ASC between 1997 and 2009, who were followed up until December 2014,were retrospectively studied at the Center for Childhood Liver Disease, Department of Pediatrics of the University Hospital in Olomouc. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and written informed consent was obtained from parents/legal representatives of all children included in the study.

Diagnosis of SC was dependent on typical cholangiographic findings on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in all patients. The extent of bile duct abnormalities was determined according to Wilschanski et al.[9]Different causes of chronic liver disease, such as hepatotropic viral infections, Wilson' s disease, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, cystic fibrosis,toxic liver disease including cases associated with longterm parenteral nutrition, were ruled out in all patients. Patients with PSC of small bile ducts, neonatal SC and secondary SC (resulting from injury, tumor, surgical procedure, congenital disorder or immunodeficiency) were excluded from the study. A blind liver biopsy using the Menghini needle and colonoscopy including colon biopsy were performed at the time of diagnosis in all patients whose parents provided informed consent. Histological staging of the disease was based on Ludwig's histological classification,[10]and simplified diagnostic criteria of the IAIHG for probable or definite AIH,[11]modified for pediatric age,[5]were used for ASC confirmation.

Pharmacological, invasive endoscopic and surgical treatment was evaluated in all patients. Biochemical relapse was defined by increased levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) being more than two times higher than the upper reference value. Obstructive cholangitis,portal hypertension, advanced liver disease (Child-Pugh class B or C) and death associated with the primary disease were considered serious complications of SC.

Results

Clinical presentation

Of the 28 patients originally diagnosed with SC, 25 patients (14 boys and 11 girls) were included in the study (Table 1). Two patients were lost to follow-up and one patient underwent bone marrow transplantation for bone marrow aplasia, which developed 6 months after PSC diagnosis, and was not further followed up at our department. The median age at the time of diagnosis was 15 years (range 3-17); 14 years (range 3-17) in patients with ASC vs 15 years (range 12-17) in patients with PSC (P=0.03). The ratio of boys to girls was 5/6 in patients with ASC and 9/5 in those with PSC. The average duration of follow-up was 11.2 years (range 4-17, median 12, no significant difference between the ASC and PSC groups). The most commonly presented symptoms at the time of diagnosis, whose frequencies were also not different significantly between the two groups, were abdominal pain (36%), fatigue (24%), diarrhea (28%), weight loss or poor appetite (12%), subfebrile temperature (16%),arthralgia or myalgia (8%) and an acute onset of SC with jaundice, vomiting, and abdominal pain (16%).

Laboratory findings

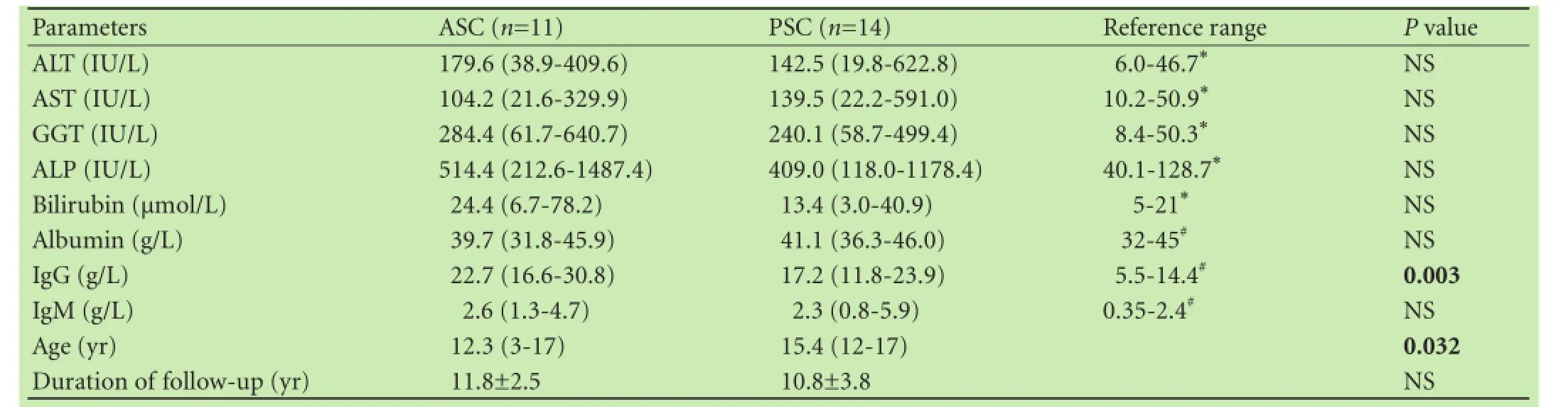

According to the modified diagnostic criteria for AIH,ASC was confirmed in 11 (44%) patients, including 5 patients with probable AIH and 6 patients with definite AIH. GGT was elevated in all 25 patients whereas alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was significantly elevated only in 7 patients. There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding ALT, AST, GGT, ALP and IgM levels (Table 2). On the contrary, patients with ASC had higher IgG levels (P=0.003). There was no significant difference in the positivity of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) between the two groups (11 patients with ASC, 11 with PSC, P=0.24), but all other antibodies were present exclusively in patients with ASC [antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in 6 patients, anti-smooth muscle antibodies (SMA) in 2, anti-soluble liver antigen antibodies(SLA) in 1, and anti-liver kidney microsomal antibodies (anti-LKM) in 1].

Table 2. Biochemical results and age of patients with SC at diagnosis and follow-up duration

Cholangiography and histology

At the time of diagnosis, ERCP was performed in 21 patients and MRCP in 4. Sixteen (64%) patients had involvement of the extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts,5 (20%) patients had isolated involvement of the intrahepatic bile ducts, and 4 (16%) patients had involvement of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Eighteen (72%) patients had mild bile duct changes (Wilschanski grade 1 and 2), whereas 7 (28%) patients exhibited severe bile duct involvement (Wilschanski grade 3 and 4). There was no difference in the extent of bile duct involvement between the ASC and PSC groups (Table 1). Follow-up MRCP was performed biennially, and progression of the bile duct involvement was found in only 3 patients during the follow-up. Histological results displayed no significant differences between patients with ASC and those with PSC.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

At the time of SC diagnosis, IBD was endoscopically and histologically confirmed in 15 (60%) patients. The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis was reassessed to Crohn disease in 2 patients during the follow-up, and at the end of follow-up IBD was present in 19 (76%) patients. Again, there was no significant difference in the incidence or distribution of IBD types between the ASC and PSC groups (ulcerative colitis: 5 vs 6 patients, Crohn disease: 2 vs 3 patients, microscopic colitis: 1 vs 2 patients,respectively).

Treatment and prognosis

All children received ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA)in a dose of 15-20 mg/kg per day. Two patients with ASC and 5 patients with PSC were treated with UDCA monotherapy, other patients (9 patients with ASC and 9 patients with PSC) with UDCA in combination with corticosteroids (prednisone 1-2 mg/kg per day). Steroid therapy was given to patients with clinically and histologically active IBD or presence of autoimmune traits (such as positivity of ANA, SMA and/or anti-LKM, increased levels of IgG and liver histology compatible with AIH or typical for AIH) even if diagnostic criteria for ASC were not fulfilled.

In 2 of 7 patients (1 patient with ASC and 1 patient with PSC) originally treated with UDCA monotherapy,corticosteroids were added due to biochemical relapse;however, only the patient with ASC showed remission.

In 6 patients (3 children with ASC and 3 children with PSC), the combination of UDCA and corticosteroids was augmented by azathioprine (1-2 mg/kg per day) due to relapse or inability to achieve remission and subsequently 2 of these patients (both patients with ASC)showed remission. Thus, in total, long-term biochemical remission was achieved in 9 patients with ASC and in 8 patients with PSC.

Elevated aminotransferase levels were present in 4 patients (2 patients with PSC and 2 patients with ASC).

In one ASC patient with biochemical relapse, progression of bile duct changes was revealed by follow-up MRCP 3 years after diagnosis. The other ASC patient underwent subtotal colectomy due to histologically confirmed mucosal dysplasia in the ascending colon and relapse occurred 5 years after surgery without changes on MRCP. Both PSC patients with biochemical relapse had histological activity grade 3 and deteriorating significant changes of the bile ducts (Wilschanski 3-4) on follow-up MRCP.

Complications and survival rates

Severe complications of SC occurred in 4 patients (16%, all of these patients had PSC): one died from colorectal cancer 6 years after SC diagnosis and 3 re-quired therapeutic ERCP for acute cholangitis. One of these 3 patients suffered from recurrent suppurative cholangitis and progression of liver disease. The patient had undergone repeated balloon dilations due to dominant stenosis of the common bile duct and liver transplantation was performed 3 years after diagnosis as the only causal therapy. The other two patients with dominant bile duct stenosis had severe liver disease histologically classified as grade 3 and 4, respectively. Both were treated with balloon dilation and stent placement. Endoscopic treatment failed in the patient with grade 4 (liver cirrhosis), therefore a surgical resection of the bile ducts was performed resulting in normalization of liver functions including aminotransferase levels. Neither hepatobiliary malignancy nor esophageal varices were present in any of the patients. Besides the studied complications,one patient experienced intracerebral hemorrhage from a ruptured aneurysm at the age of 29 years.

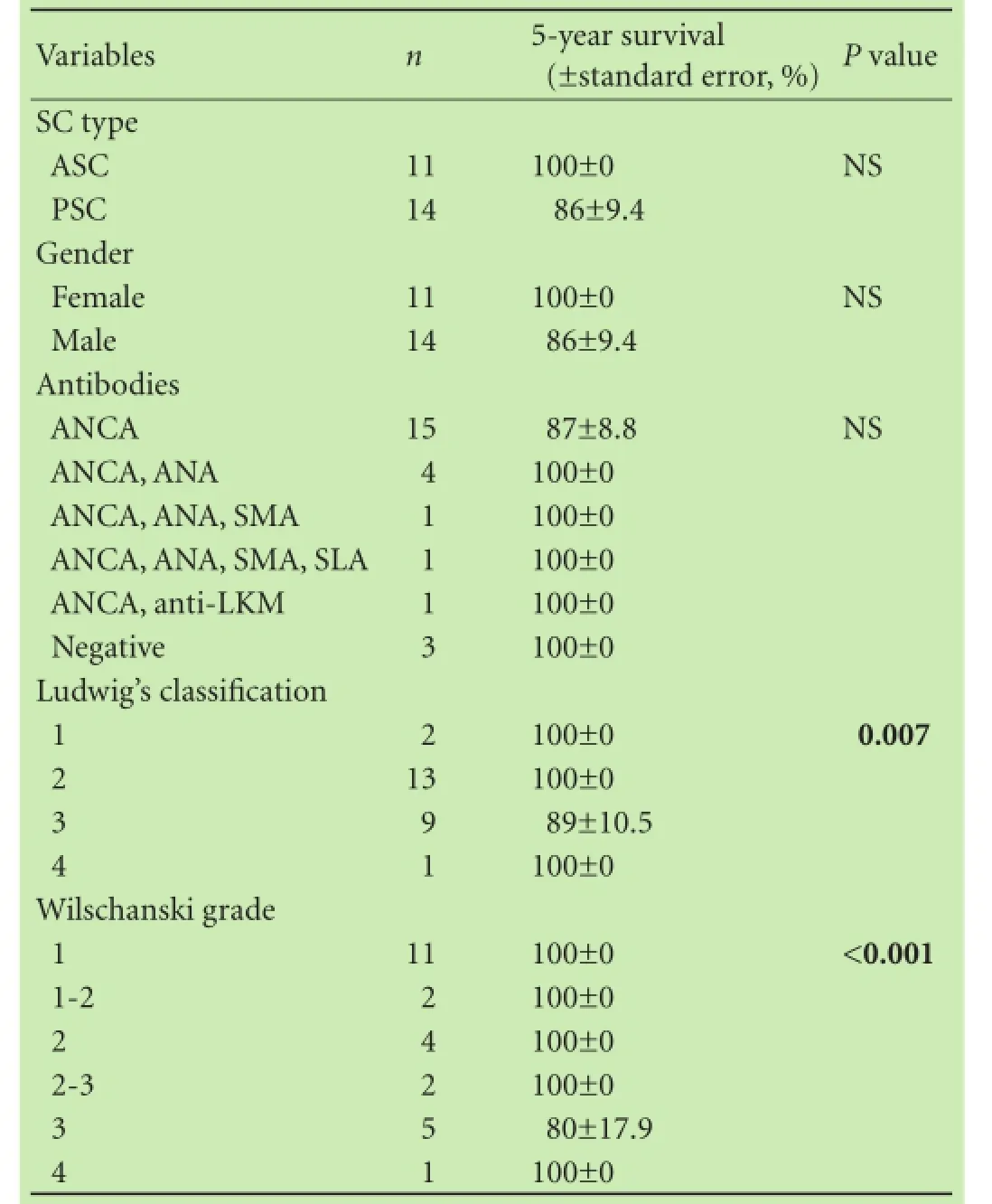

The 5- and 10-year overall survival rates for all patients with SC were 100% and (95.8±4.1)%, respectively:only 1 death (6 years after SC diagnosis) was recorded within our cohort of 25 patients. The 10-year overall survival rate was 100% (21 of 21 patients) in patients without complicated liver disease and (75.0±21.7)% (3 of 4 patients) in patients with complications (Fig. A). All 11 patients with ASC and 10/14, i.e. (70.7±12.4)% patients with PSC were alive without complications after 10 years (P=0.063; Fig. B, Table 1). Univariate analysis revealed that only Ludwig's classification and Wilschanski grade were significantly associated with survival (P=0.007 and P<0.001, respectively; Table 3). However, the number of patients was too small for multivariate analysis.

Fig. A: Overall survival in patients with SC; B: Time to the onset of complications in patients with ASC and PSC. SC: sclerosing cholangitis; ASC: autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Table 3. Risk factors for the survival of children with SC: univariate analysis

Discussion

We retrospectively reviewed pediatric patients treated for SC in a single tertiary referral center in the Czech Republic which covers a region with approximately 15 000 children born annually. The number of children with SC in our study is larger than the reported incidence of SC in both pediatric and adult patients;[6, 12]however, pos-sible geographical and racial differences must be considered.[13]We have not observed an increase in juvenile autoimmune liver disease over the last two decades as published.[14]In PSC, males predominated over females and the ratio of boys to girls with ASC was in accordance with the literature;[4, 5]however, the number of patients was small.

Using the simplified scoring system for AIH, the proportion of children with ASC was 44%, which is higher than that of children and adults in previous studies.[6, 7, 9, 12]In contrast to Floreani et al,[15]we have not observed different levels of biochemical markers in patients with ASC except for higher IgG levels. The fact that increased GGT levels are more frequent in SC than increased ALP levels and may thus represent a diagnostic marker was discussed;[7, 8, 16]however, prospective studies showed that early stages of ASC are not particularly cholestatic and can have normal levels of GGT.[4]In our study, none or only nonspecific clinical symptoms were seen in the initial stage of SC.

All patients except of one with ASC presented with histological signs of bile duct abnormalities, whereas Gregorio et al[4]reported that there were no histological changes in the bile ducts in almost one quarter of children with ASC.

The frequent occurrence of IBD in our children with SC is consistent with that reported in the literature.[17, 18]PSC is an independent risk factor for the development of colorectal cancer. Patients with PSC and concurrent IBD have an increased risk for the development of colonic malignancies and tend to have more advanced tumors and worse overall prognosis. Furthermore, different pathogenesis between patients with IBD and PSC and those with IBD alone is suggested.[19, 20]The cumulative incidence of colorectal cancer in adults with PSC and concurrent IBD is approximately 5% after 10 years;[21]however, it is extremely rare in children during the first eight years after SC diagnosis.[22]The development of colorectal cancer in our patient may have been influenced by the late diagnosis and delayed start of the UDCA treatment. The presence of dysplasia at diagnosis,such as was seen in our patient, was surprisingly more frequent in adult patients with IBD[23]and should be taken into consideration as soon as during the first colonoscopy at diagnosis of SC. We have not observed lower prevalence of IBD among patients with ASC than in patients with PSC in contrast to Floreani et al.[15]

Treatment with UDCA has favorable effect on the levels of bilirubin and aminotransferases and improves histological and cholangiographic findings. However, it did not prolong the time between diagnosis and transplantation and the evidence that it improves the overall prognosis of SC is lacking.[24]All our patients were treated with UDCA and the favorable course of their disease with lower occurrence of severe complications could have been attributed to the early stage of the disease and timely initiation of UDCA therapy.[7, 8]The administration of corticosteroids, azathioprine or other immunosuppressants is not recommended for the treatment of PSC.[25, 26]We implemented this non-standard therapy in patients with a presence of distinct autoimmune traits as soon as in the 1990s when data regarding SC treatment in children were scarce.

In terms of biochemical relapse, only 2 children from our ASC cohort had elevated aminotransferase levels. This better outcome in patients with autoimmune features is in consistent with the result reported by Floreani et al.[3, 15]but more optimistic compared with Feldstein et al[7]where the long-term outcomes of patients with ASC and PSC were similar. Better prognosis of children with SC might result from an early diagnosis in a stage of low histological activity and less severe fibrosis.[6, 8]Histologically, most patients are diagnosed in advanced stages of SC whereas in those diagnosed in early stages of the disease histological findings do not predict the future disease course.[27]Elevated aminotransferase levels indicated disease progression and were associated with progression of cholangiographic findings as documented on follow-up MRCP. The relation to elevated aminotransferase levels remains unclear in patient after subtotal colectomy.

According to the histologic and cholangiographic findings, the majority of our patients were diagnosed during an early stage of SC. This is likely reflected by a small number of patients indicated for liver transplant (4% in our study in contrast to 17%-21% reported elsewhere).[6-8]Endoscopic intervention for acute cholangitis was performed in a similar proportion of patients to the reported 10%-17%.[8]The estimated occurrence of dominant bile duct stenosis is 10%-20% and the prognosis of these patients is significantly worse.[21]In our study, no patient was diagnosed with malignancy of the biliary tract; however, this might depend on the length of follow-up. Histological examination was performed in all patients with dominant biliary strictures; specimens were obtained by ERCP in 2 patients, from surgical bile duct resection in 1 and after liver transplantation in 1. In summary, we observed inferior overall survival in patients with SC complications compared to other patients (approximately 75% vs 100%); however, the number of patients with complications was small and only one patient who died of colorectal cancer was recorded.

The limitations of this study are its retrospective nature and the absence of multivariate analysis because of the limited number of patients. Furthermore, followup liver biopsy was not performed and condition of the liver and biliary system was followed only by MRCP and biochemical analysis. However, we consider that SC inour region was more frequent than in Canada and the United States.[1, 6]In our study, the majority of patients were diagnosed in early stages of SC and therefore their prognosis was better. Patients with ASC were younger,had higher levels of IgG and responded better to immunosuppressive treatment. Prospective multicenter studies are required to identify the most relevant prognostic factors and determine optimal pharmacological treatment and indications for interventional procedures.

Acknowledgement: We thank Dr. Jana Vrbkova for assistance with statistical analysis.

Contributors: SV proposed the study. SV and VJ wrote the first draft. SV, KE, TO and VJ collected and analyzed the data. SV, KE and TO managed patients; AK and KM performed endoscopic examinations; EJ evaluated histology; MK was responsible for radiological findings. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. SV is the guarantor. Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (NPU LO 1304).

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Palacky University and University Hospital Olomouc.

Competing interest: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

1 Kaplan GG, Laupland KB, Butzner D, Urbanski SJ, Lee SS. The burden of large and small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis in adults and children: a population-based analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1042-1049.

2 el-Shabrawi M, Wilkinson ML, Portmann B, Mieli-Vergani G,Chong SK, Williams R, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis in childhood. Gastroenterology 1987;92:1226-1235.

3 Floreani A, Zancan L, Melis A, Baragiotta A, Chiaramonte M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC): clinical, laboratory and survival analysis in children and adults. Liver 1999;19:228-233.

4 Gregorio GV, Portmann B, Karani J, Harrison P, Donaldson PT,Vergani D, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis/sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome in childhood: a 16-year prospective study. Hepatology 2001;33:544-553.

5 Mileti E, Rosenthal P, Peters MG. Validation and modification of simplified diagnostic criteria for autoimmune hepatitis in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:417-421.

6 Deneau M, Jensen MK, Holmen J, Williams MS, Book LS,Guthery SL. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and overlap in Utah children: epidemiology and natural history. Hepatology 2013;58:1392-1400.

7 Feldstein AE, Perrault J, El-Youssif M, Lindor KD, Freese DK,Angulo P. Primary sclerosing cholangitis in children: a longterm follow-up study. Hepatology 2003;38:210-217.

8 Miloh T, Arnon R, Shneider B, Suchy F, Kerkar N. A retrospective single-center review of primary sclerosing cholangitis in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:239-245.

9 Wilschanski M, Chait P, Wade JA, Davis L, Corey M, St Louis P, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis in 32 children: clinical,laboratory, and radiographic features, with survival analysis. Hepatology 1995;22:1415-1422.

10 Ludwig J, LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. In: Peters RL, Craig JG, eds. Contemporary Issues in Surgical Pathology: Liver Pathology. Churchill Livingstone,New York; 1986:193-213.

11 Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK,Cancado EL, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 1999;31:929-938.

12 Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol 2012;56:1181-1188.

13 Rojas CP, Bodicharla R, Campuzano-Zuluaga G, Hernandez L,Rodriguez MM. Autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis in children and adolescents. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2014;33:202-209.

14 Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Paediatric autoimmune liver disease. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:1012-1017.

15 Floreani A, Rizzotto ER, Ferrara F, Carderi I, Caroli D, Blasone L, et al. Clinical course and outcome of autoimmune hepatitis/ primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:1516-1522.

16 Shneider BL. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in pediatric primary sclerosing cholangitis. Liver Transpl 2012;18:277-281.

17 Kerkar N, Miloh T. Sclerosing cholangitis: pediatric perspective. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2010;12:195-202.

18 Noble-Jamieson G, Heuschkel RB, Torrente F, Hadzic N, Zilbauer M. Colitis-associated sclerosing cholangitis in children:a single centre experience. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:e414-418.

19 Soetikno RM, Lin OS, Heidenreich PA, Young HS, Blackstone MO. Increased risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: a metaanalysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:48-54.

20 Claessen MM, Lutgens MW, van Buuren HR, Oldenburg B,Stokkers PC, van der Woude CJ, et al. More right-sided IBD-associated colorectal cancer in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:1331-1336.

21 Talwalkar JA, Lindor KD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005;11:62-72.

22 Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, Itzkowitz SH, McCabe RP, Dassopoulos T, et al. AGA medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2010;138:738-745.

23 Boonstra K, van Erpecum KJ, van Nieuwkerk KM, Drenth JP,Poen AC, Witteman BJ, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is associated with a distinct phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:2270-2276.

24 Shi J, Li Z, Zeng X, Lin Y, Xie WF. Ursodeoxycholic acid in primary sclerosing cholangitis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hepatol Res 2009;39:865-873.

25 Hirschfield GM, Karlsen TH, Lindor KD, Adams DH. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet 2013;382:1587-1599.

26 Ibrahim SH, Lindor KD. Current management of primary sclerosing cholangitis in pediatric patients. Paediatr Drugs 2011;13:87-95.

27 Batres LA, Russo P, Mathews M, Piccoli DA, Chuang E, Ruchelli E. Primary sclerosing cholangitis in children: a histologic follow-up study. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2005;8:568-576.

Accepted after revision December 22, 2015

Author Affiliations: Department of Pediatrics (Smolka V, Karaskova E,Tkachyk O and Volejnikova J), Department of Internal Medicine (Aiglova K and Konecny M), Department of Clinical and Molecular Pathology (Ehrmann J), and Department of Radiology (Michalkova K), Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Palacky University and University Hospital Olomouc, I. P. Pavlova 6, Olomouc 779 00, Czech Republic

Vratislav Smolka, MD, Department of Pediatrics,Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Palacky University and University Hospital Olomouc, I. P. Pavlova 6, Olomouc 779 00, Czech Republic (Tel:+420-58844-4493; Fax: +420-58844-4403; Email: vratislav.smolka@fnol.cz)© 2016, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(16)60088-7

Published online April 20, 2016.

July 23, 2015

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International

- Dietary supplementation in patients with alcoholic liver disease: a review on current evidence

- Combined hepatectomy and radiofrequency ablation versus TACE in improving survival of patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC

- Effects of Salmonella infection on hepatic damage following acute liver injury in rats

- Letters to the Editor

- Kidney transplantation after liver transplantation